User login

Can sleep apnea be accurately diagnosed at home?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 50-year-old overweight male with a history of hypertension presents to your office for a yearly physical. On review of symptoms, he notes feeling constantly tired, despite reported good sleep hygiene practices. He scores 11 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and his wife complains about his snoring. You have a high suspicion of obstructive sleep apnea. What is your next step?

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is quite common, affecting at least 2% to 4% of the general adult population.2 The gold standard for OSA diagnosis has been laboratory polysomnography (PSG) to measure the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), which is the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, and the respiratory event index (REI), which is the average number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory effort-related arousals per hour of sleep. A minimum of 5 on the AHI or REI, along with clinical symptoms, is required for diagnosis.

Many adults go undiagnosed and untreated, however, due to barriers to diagnosis including the inconvenience of laboratory PSG.3 Sleep laboratories often have a significant wait time for evaluation, and sleeping in an unfamiliar place can be inconvenient or intolerable for some patients, making diagnosis difficult despite high clinical suspicion. Untreated sleep apnea is associated with an increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes.4

Home sleep studies are an alternative for patients with a high risk of OSA without comorbid sleep conditions, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This study investigated the long-term effectiveness of diagnosis by home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) vs laboratory PSG in patients with an intermediate to high clinical suspicion for OSA.

STUDY SUMMARY

Home Dx is noninferior to lab Dx in all aspects studied

This multicenter, noninferiority randomized controlled trial and cost analysis study conducted in Spain randomized 430 adults referred to pulmonology for suspected OSA to receive either in-lab PSG or HRP. Patients received treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) if their REI was ≥ 5 for HRP or their AHI was ≥ 5 for PSG with significant clinical symptoms, which is consistent with the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines.5 All patients in both arms received sleep hygiene instruction, nutrition education, and single-session auto-CPAP titration, and were evaluated at 1 and 3 months to assess for compliance. At 6 months, all patients were evaluated with PSG.

HRP was found to be non-inferior to PSG based on Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores evaluated at baseline and at 6-month follow-up (HRP mean = -4.2 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -4.8 to -3.6 and PSG mean -4.9; 95% CI, -5.4 to -4.3; P = .14). Both groups had similar secondary outcomes. Quality-of-life as measured by the 30-point Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire improved by an average of 6.7 (standard deviation [SD] = 16.7) in the HRP group vs 6.5 (SD = 18.1) in the PSG group (P = .92). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure improved significantly in both groups without any statistically significant difference between the groups. HRP was also found to be more cost-effective than PSG with a savings equivalent to more than half the cost of PSG, or about $450 per study (depending on the exchange rate).

WHAT’S NEW

HRP offers advantages for low-risk patients

In the majority of patients, OSA can be diagnosed at home with outcomes similar to those for lab diagnosis, decreased cost, and decreased time from suspected diagnosis to treatment. HRP is acceptable for patients with a high probability of OSA without significant comorbidities if monitoring includes at least airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation.6

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Recommendations are somewhat ambiguous

This study, as well as current guidelines, recommend home sleep studies for patients with a high clinical suspicion or high pre-test probability of OSA and who lack comorbid conditions that could affect sleep. The comorbid conditions are well identified: COPD, heart failure hypoventilation syndromes, insomnia, hypersomnia, parasomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, narcolepsy, and chronic opioid use.6 However, what constitutes “a high clinical suspicion” or “high pre-test probability” was not well defined in this study.

Several clinical screening tools are available and include the ESS, Berlin Questionnaire, and STOP-BANG Scoring System (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, Pressure [systemic hypertension], Body mass index > 35, Age > 50 years, Neck circumference > 16 inches, male Gender). An ESS score ≥ 10 warrants further evaluation, but is not very sensitive. Two or more positive categories on the Berlin Questionnaire indicates a high risk of OSA with a sensitivity of 76%, 77%, and 77% for mild, moderate, and severe OSA, respectively.7 A score of ≥ 3 on the STOP-BANG Scoring System has been validated and has a sensitivity of 83.6%, 92.9%, and 100% for an AHI > 5, > 15, and > 30, respectively.8

Home sleep studies should not be used to screen the general population.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Recommendations may present a challenge but insurance should not

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that portable monitoring must record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation, and the device must be able to display the raw data to be interpreted by a board-certified sleep medicine physician according to current published standards.6 Implementation would require appropriate selection of a home monitoring device, consultation with a sleep medicine specialist, and significant patient education to ensure interpretable results.

Insurance should not be a barrier to implementation as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accept home sleep apnea testing results for CPAP prescriptions.9 However, variability currently exists regarding the extent to which private insurers provide coverage for home sleep apnea testing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga MÁ, Carmona-Bernal C, et al. Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1181-1190.

2. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263-276.

3. Colten H, Abboud F, Block G, et al. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. 2006. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

4. Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136-143.

5. Lloberes P, Durán-Cantolla J, Martinez-Garcia MA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:143-156.

6. Rosen IM, Kirsch DB, Chervin RD; American Academy of Sleep Medicine Board of Directors. Clinical use of a home sleep apnea test: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:1205-1207.

7. Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang, LP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP and Epworth Sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57-70.

8. Chung, F, Yegneswaran B, Lio P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812-821.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (CAG-00093R2). March 13, 2008. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=204. Accessed September 6, 2019.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 50-year-old overweight male with a history of hypertension presents to your office for a yearly physical. On review of symptoms, he notes feeling constantly tired, despite reported good sleep hygiene practices. He scores 11 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and his wife complains about his snoring. You have a high suspicion of obstructive sleep apnea. What is your next step?

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is quite common, affecting at least 2% to 4% of the general adult population.2 The gold standard for OSA diagnosis has been laboratory polysomnography (PSG) to measure the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), which is the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, and the respiratory event index (REI), which is the average number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory effort-related arousals per hour of sleep. A minimum of 5 on the AHI or REI, along with clinical symptoms, is required for diagnosis.

Many adults go undiagnosed and untreated, however, due to barriers to diagnosis including the inconvenience of laboratory PSG.3 Sleep laboratories often have a significant wait time for evaluation, and sleeping in an unfamiliar place can be inconvenient or intolerable for some patients, making diagnosis difficult despite high clinical suspicion. Untreated sleep apnea is associated with an increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes.4

Home sleep studies are an alternative for patients with a high risk of OSA without comorbid sleep conditions, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This study investigated the long-term effectiveness of diagnosis by home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) vs laboratory PSG in patients with an intermediate to high clinical suspicion for OSA.

STUDY SUMMARY

Home Dx is noninferior to lab Dx in all aspects studied

This multicenter, noninferiority randomized controlled trial and cost analysis study conducted in Spain randomized 430 adults referred to pulmonology for suspected OSA to receive either in-lab PSG or HRP. Patients received treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) if their REI was ≥ 5 for HRP or their AHI was ≥ 5 for PSG with significant clinical symptoms, which is consistent with the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines.5 All patients in both arms received sleep hygiene instruction, nutrition education, and single-session auto-CPAP titration, and were evaluated at 1 and 3 months to assess for compliance. At 6 months, all patients were evaluated with PSG.

HRP was found to be non-inferior to PSG based on Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores evaluated at baseline and at 6-month follow-up (HRP mean = -4.2 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -4.8 to -3.6 and PSG mean -4.9; 95% CI, -5.4 to -4.3; P = .14). Both groups had similar secondary outcomes. Quality-of-life as measured by the 30-point Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire improved by an average of 6.7 (standard deviation [SD] = 16.7) in the HRP group vs 6.5 (SD = 18.1) in the PSG group (P = .92). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure improved significantly in both groups without any statistically significant difference between the groups. HRP was also found to be more cost-effective than PSG with a savings equivalent to more than half the cost of PSG, or about $450 per study (depending on the exchange rate).

WHAT’S NEW

HRP offers advantages for low-risk patients

In the majority of patients, OSA can be diagnosed at home with outcomes similar to those for lab diagnosis, decreased cost, and decreased time from suspected diagnosis to treatment. HRP is acceptable for patients with a high probability of OSA without significant comorbidities if monitoring includes at least airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation.6

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Recommendations are somewhat ambiguous

This study, as well as current guidelines, recommend home sleep studies for patients with a high clinical suspicion or high pre-test probability of OSA and who lack comorbid conditions that could affect sleep. The comorbid conditions are well identified: COPD, heart failure hypoventilation syndromes, insomnia, hypersomnia, parasomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, narcolepsy, and chronic opioid use.6 However, what constitutes “a high clinical suspicion” or “high pre-test probability” was not well defined in this study.

Several clinical screening tools are available and include the ESS, Berlin Questionnaire, and STOP-BANG Scoring System (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, Pressure [systemic hypertension], Body mass index > 35, Age > 50 years, Neck circumference > 16 inches, male Gender). An ESS score ≥ 10 warrants further evaluation, but is not very sensitive. Two or more positive categories on the Berlin Questionnaire indicates a high risk of OSA with a sensitivity of 76%, 77%, and 77% for mild, moderate, and severe OSA, respectively.7 A score of ≥ 3 on the STOP-BANG Scoring System has been validated and has a sensitivity of 83.6%, 92.9%, and 100% for an AHI > 5, > 15, and > 30, respectively.8

Home sleep studies should not be used to screen the general population.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Recommendations may present a challenge but insurance should not

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that portable monitoring must record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation, and the device must be able to display the raw data to be interpreted by a board-certified sleep medicine physician according to current published standards.6 Implementation would require appropriate selection of a home monitoring device, consultation with a sleep medicine specialist, and significant patient education to ensure interpretable results.

Insurance should not be a barrier to implementation as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accept home sleep apnea testing results for CPAP prescriptions.9 However, variability currently exists regarding the extent to which private insurers provide coverage for home sleep apnea testing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 50-year-old overweight male with a history of hypertension presents to your office for a yearly physical. On review of symptoms, he notes feeling constantly tired, despite reported good sleep hygiene practices. He scores 11 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and his wife complains about his snoring. You have a high suspicion of obstructive sleep apnea. What is your next step?

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is quite common, affecting at least 2% to 4% of the general adult population.2 The gold standard for OSA diagnosis has been laboratory polysomnography (PSG) to measure the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), which is the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, and the respiratory event index (REI), which is the average number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory effort-related arousals per hour of sleep. A minimum of 5 on the AHI or REI, along with clinical symptoms, is required for diagnosis.

Many adults go undiagnosed and untreated, however, due to barriers to diagnosis including the inconvenience of laboratory PSG.3 Sleep laboratories often have a significant wait time for evaluation, and sleeping in an unfamiliar place can be inconvenient or intolerable for some patients, making diagnosis difficult despite high clinical suspicion. Untreated sleep apnea is associated with an increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes.4

Home sleep studies are an alternative for patients with a high risk of OSA without comorbid sleep conditions, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This study investigated the long-term effectiveness of diagnosis by home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) vs laboratory PSG in patients with an intermediate to high clinical suspicion for OSA.

STUDY SUMMARY

Home Dx is noninferior to lab Dx in all aspects studied

This multicenter, noninferiority randomized controlled trial and cost analysis study conducted in Spain randomized 430 adults referred to pulmonology for suspected OSA to receive either in-lab PSG or HRP. Patients received treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) if their REI was ≥ 5 for HRP or their AHI was ≥ 5 for PSG with significant clinical symptoms, which is consistent with the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines.5 All patients in both arms received sleep hygiene instruction, nutrition education, and single-session auto-CPAP titration, and were evaluated at 1 and 3 months to assess for compliance. At 6 months, all patients were evaluated with PSG.

HRP was found to be non-inferior to PSG based on Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores evaluated at baseline and at 6-month follow-up (HRP mean = -4.2 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -4.8 to -3.6 and PSG mean -4.9; 95% CI, -5.4 to -4.3; P = .14). Both groups had similar secondary outcomes. Quality-of-life as measured by the 30-point Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire improved by an average of 6.7 (standard deviation [SD] = 16.7) in the HRP group vs 6.5 (SD = 18.1) in the PSG group (P = .92). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure improved significantly in both groups without any statistically significant difference between the groups. HRP was also found to be more cost-effective than PSG with a savings equivalent to more than half the cost of PSG, or about $450 per study (depending on the exchange rate).

WHAT’S NEW

HRP offers advantages for low-risk patients

In the majority of patients, OSA can be diagnosed at home with outcomes similar to those for lab diagnosis, decreased cost, and decreased time from suspected diagnosis to treatment. HRP is acceptable for patients with a high probability of OSA without significant comorbidities if monitoring includes at least airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation.6

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Recommendations are somewhat ambiguous

This study, as well as current guidelines, recommend home sleep studies for patients with a high clinical suspicion or high pre-test probability of OSA and who lack comorbid conditions that could affect sleep. The comorbid conditions are well identified: COPD, heart failure hypoventilation syndromes, insomnia, hypersomnia, parasomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, narcolepsy, and chronic opioid use.6 However, what constitutes “a high clinical suspicion” or “high pre-test probability” was not well defined in this study.

Several clinical screening tools are available and include the ESS, Berlin Questionnaire, and STOP-BANG Scoring System (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, Pressure [systemic hypertension], Body mass index > 35, Age > 50 years, Neck circumference > 16 inches, male Gender). An ESS score ≥ 10 warrants further evaluation, but is not very sensitive. Two or more positive categories on the Berlin Questionnaire indicates a high risk of OSA with a sensitivity of 76%, 77%, and 77% for mild, moderate, and severe OSA, respectively.7 A score of ≥ 3 on the STOP-BANG Scoring System has been validated and has a sensitivity of 83.6%, 92.9%, and 100% for an AHI > 5, > 15, and > 30, respectively.8

Home sleep studies should not be used to screen the general population.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Recommendations may present a challenge but insurance should not

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that portable monitoring must record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation, and the device must be able to display the raw data to be interpreted by a board-certified sleep medicine physician according to current published standards.6 Implementation would require appropriate selection of a home monitoring device, consultation with a sleep medicine specialist, and significant patient education to ensure interpretable results.

Insurance should not be a barrier to implementation as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accept home sleep apnea testing results for CPAP prescriptions.9 However, variability currently exists regarding the extent to which private insurers provide coverage for home sleep apnea testing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga MÁ, Carmona-Bernal C, et al. Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1181-1190.

2. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263-276.

3. Colten H, Abboud F, Block G, et al. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. 2006. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

4. Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136-143.

5. Lloberes P, Durán-Cantolla J, Martinez-Garcia MA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:143-156.

6. Rosen IM, Kirsch DB, Chervin RD; American Academy of Sleep Medicine Board of Directors. Clinical use of a home sleep apnea test: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:1205-1207.

7. Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang, LP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP and Epworth Sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57-70.

8. Chung, F, Yegneswaran B, Lio P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812-821.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (CAG-00093R2). March 13, 2008. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=204. Accessed September 6, 2019.

1. Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga MÁ, Carmona-Bernal C, et al. Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1181-1190.

2. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263-276.

3. Colten H, Abboud F, Block G, et al. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. 2006. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

4. Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136-143.

5. Lloberes P, Durán-Cantolla J, Martinez-Garcia MA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:143-156.

6. Rosen IM, Kirsch DB, Chervin RD; American Academy of Sleep Medicine Board of Directors. Clinical use of a home sleep apnea test: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:1205-1207.

7. Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang, LP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP and Epworth Sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57-70.

8. Chung, F, Yegneswaran B, Lio P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812-821.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (CAG-00093R2). March 13, 2008. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=204. Accessed September 6, 2019.

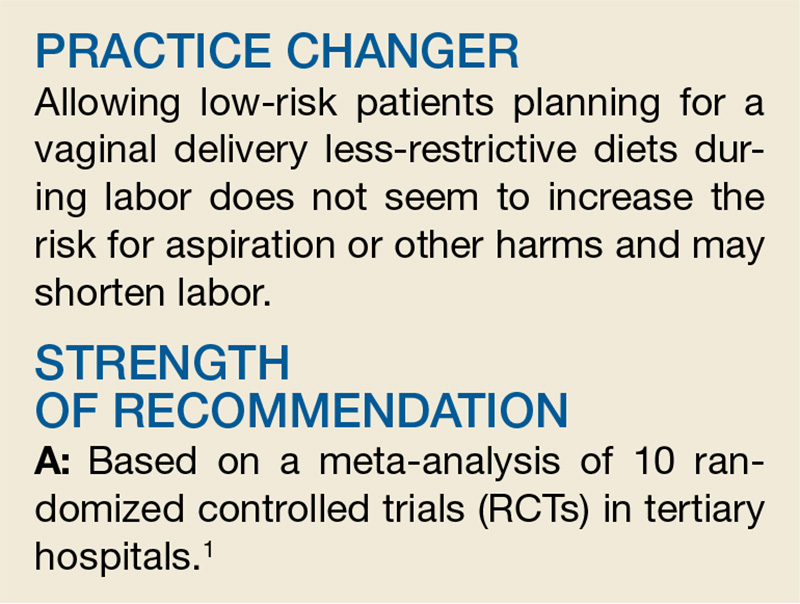

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider ordering home respiratory polygraphy vs laboratory sleep studies for patients suspected of having obstructive sleep apnea.1

Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga MÁ, Carmona-Bernal C, et al. Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1181-1190.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a multicenter, noninferiority randomized controlled trial and cost analysis study.

Let Low-risk Moms Eat During Labor?

A 23-year-old nulliparous woman at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the past three hours and says she’s hungry. What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s, many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less, with little evidence to support the decision.2 In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a general-population study of 172,334 adults who underwent a total of 215,488 surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk for aspiration was 1:895 for emergency procedures and 1:3886 for elective procedures.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less-restrictive diet during labor.

STUDY SUMMARY

Not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3,982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥ 37 weeks, two studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥ 30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Continue to: Results

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes. Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal ICU were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk, 1.00). None of the 3,982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

An outdated practice, per the data

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk for complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less-restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[6]:379-380).

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, Berghella V. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(11):1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(1):56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):171-175.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

A 23-year-old nulliparous woman at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the past three hours and says she’s hungry. What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s, many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less, with little evidence to support the decision.2 In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a general-population study of 172,334 adults who underwent a total of 215,488 surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk for aspiration was 1:895 for emergency procedures and 1:3886 for elective procedures.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less-restrictive diet during labor.

STUDY SUMMARY

Not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3,982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥ 37 weeks, two studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥ 30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Continue to: Results

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes. Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal ICU were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk, 1.00). None of the 3,982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

An outdated practice, per the data

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk for complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less-restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[6]:379-380).

A 23-year-old nulliparous woman at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the past three hours and says she’s hungry. What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s, many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less, with little evidence to support the decision.2 In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a general-population study of 172,334 adults who underwent a total of 215,488 surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk for aspiration was 1:895 for emergency procedures and 1:3886 for elective procedures.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less-restrictive diet during labor.

STUDY SUMMARY

Not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3,982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥ 37 weeks, two studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥ 30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Continue to: Results

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes. Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal ICU were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk, 1.00). None of the 3,982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

An outdated practice, per the data

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less-restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk for complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less-restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[6]:379-380).

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, Berghella V. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(11):1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(1):56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):171-175.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, Berghella V. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(11):1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(1):56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):171-175.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

Let low-risk moms eat during labor?

Illustrative Case

A 23-year-old nulliparous female at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the last 3 hours and says she’s hungry.

What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the diet order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson Syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s,2 many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less with little evidence to support the decision. In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a study of 172,334 patients ≥18 years of age in the general population undergoing a total of 215,488 emergency or elective surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk of aspiration was 1:895 and 1:3886, respectively.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less restrictive diet during labor.

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis finds not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥37 weeks, 2 studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes (95% confidence interval [CI], -25 to -7). Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk=1.00; 95% CI, 0.81-1.23). None of the 3982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

Restricting diets during labor is outdated

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk of complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, et al. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14:171-175.

6. Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

Illustrative Case

A 23-year-old nulliparous female at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the last 3 hours and says she’s hungry.

What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the diet order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson Syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s,2 many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less with little evidence to support the decision. In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a study of 172,334 patients ≥18 years of age in the general population undergoing a total of 215,488 emergency or elective surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk of aspiration was 1:895 and 1:3886, respectively.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less restrictive diet during labor.

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis finds not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥37 weeks, 2 studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes (95% confidence interval [CI], -25 to -7). Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk=1.00; 95% CI, 0.81-1.23). None of the 3982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

Restricting diets during labor is outdated

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk of complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Illustrative Case

A 23-year-old nulliparous female at term with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to labor and delivery. She reports regular contractions for the last several hours and is admitted in labor for an anticipated vaginal delivery. She has not had anything to eat or drink for the last 3 hours and says she’s hungry.

What type of diet should you order for this patient? Should you place any restrictions in the diet order?

Since the first reports of Mendelson Syndrome (aspiration during general anesthesia) in the early 1940s,2 many health care providers managing laboring women restrict their diets to clear liquids or less with little evidence to support the decision. In a recent survey of Canadian hospitals, for example, 51% of laboring women who did not receive an epidural during the active phase of labor were placed on restricted diets of only clear fluids and/or ice chips; this number rose to 83% for women who did receive an epidural.3

Dietary restrictions continue to be enforced despite the fact that only about 5% of obstetric patients require general anesthesia.1 In a study of 172,334 patients ≥18 years of age in the general population undergoing a total of 215,488 emergency or elective surgeries with general anesthesia, the risk of aspiration was 1:895 and 1:3886, respectively.4 Of the 66 patients who aspirated, 42 had no respiratory sequelae.

Similarly, Robinson et al noted that anesthesia-associated aspiration fatalities have been much lower in more recent studies than in historical ones—approximately 1 in 350,000 anesthesia events compared with 1 in 45,000 to 240,000—and are more commonly observed during intubation for emergency surgery.5

The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidance is to restrict oral intake to clear liquids during labor for low-risk patients, with further restriction for those at increased risk for aspiration.6 The meta-analysis described here looked at the risks and benefits of a less restrictive diet during labor.

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis finds not one case of aspiration

This meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, including 3982 laboring women, analyzed the effect of food intake on labor and the risks and benefits associated with less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.1 Women were included in the trials if they had singleton pregnancies with cephalic presentation at the time of delivery. The women had varying cervical dilation at the time of presentation. Seven of 10 studies involved women with a gestational age ≥37 weeks, 2 studies set the gestational age threshold at 36 weeks, and one study included women with a gestational age ≥30 weeks.

In the intervention groups, the authors studied varying degrees of diets and/or intakes, ranging from oral carbohydrate solutions to low-fat food to a completely unrestricted diet. One study accounted for 61% of the patients in this review and compared intake of low-fat foods to ice chips, water, or sips of water until delivery. The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was duration of labor.

Results. The authors of the meta-analysis found that the patients in the intervention groups, compared with the control groups, had a shorter mean duration of labor by 16 minutes (95% confidence interval [CI], -25 to -7). Apgar scores and the rates of Cesarean delivery, operative vaginal delivery, epidural analgesia, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit were similar in the intervention and control groups. Maternal vomiting was also similar: 37.6% in the intervention group and 36.5% in the control group (relative risk=1.00; 95% CI, 0.81-1.23). None of the 3982 patients experienced aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis.1

WHAT’S NEW

Restricting diets during labor is outdated

For years, women’s diets have been restricted during labor without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, Ciardulli and colleagues did not find a single case of aspiration pneumonitis—the outcome on which the rationale for restricting diets during labor is based. A 2013 Cochrane review by Singata et al also found no harm in less restrictive diets for low-risk women in labor.7 Ciardulli et al concluded that dietary restrictions for women at low risk of complications/surgery during labor are not justified based on current data.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Underpowered and missing information

This meta-analysis found no occurrences of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis; however, it was underpowered to identify these rare complications. This is partially due to the unusual need for general anesthesia in low-risk patients, as noted earlier. Data on the total number of women who underwent general anesthesia in the current review were limited, as not every study within the meta-analysis included this information.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Stemming the cultural tide

One challenge to implementation is changing the culture of practice regarding low-risk pregnant women in labor, as well as the opinions of other health care providers and hospital policies that oppose less restrictive oral intake during labor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, et al. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14:171-175.

6. Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

1. Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, et al. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:473-480.

2. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191-205.

3. Chackowicz A, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Restrictions on oral and parenteral intake for low-risk labouring women in hospitals across Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:1009-1014.

4. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:56-62.

5. Robinson M, Davidson A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Cont Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14:171-175.

6. Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 441. Oral intake during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:714. Reaffirmed 2017.

7. Singata M, Tranmer J, Gyte GM. Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD003930.

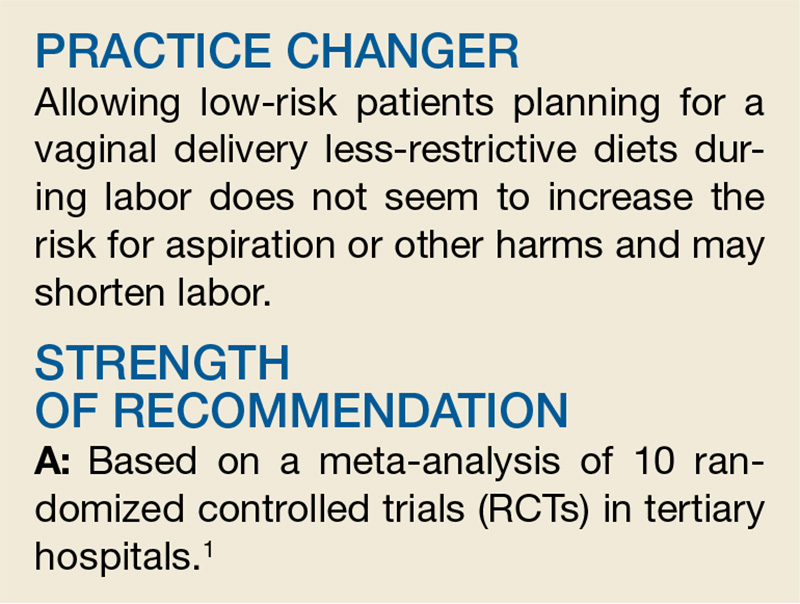

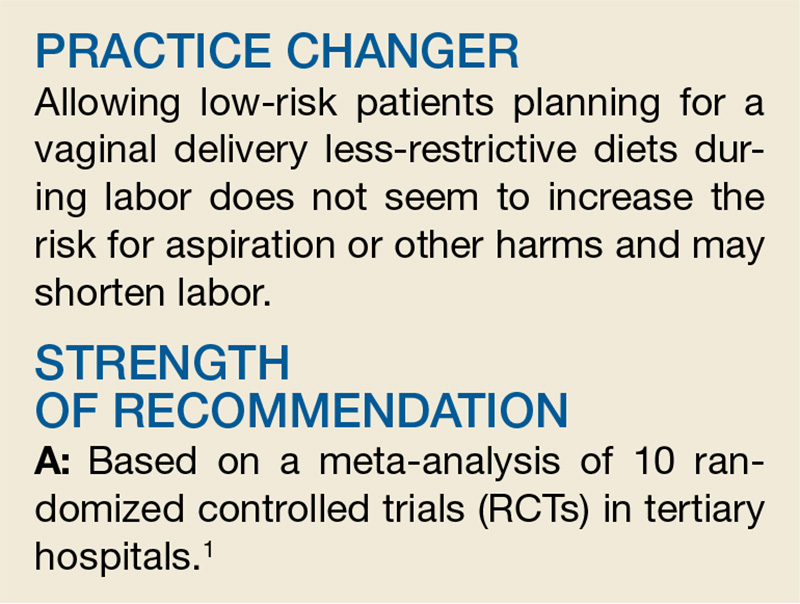

PRACTICE CHANGER

Allowing low-risk patients planning for a vaginal delivery less restrictive diets during labor does not seem to increase the risk of aspiration or other harms and may shorten labor.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in tertiary hospitals.

Ciardulli A, Saccone G, Anastasio H, et al. Less-restrictive food intake during labor in low-risk singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:473-480.

Itchy rash near the navel

An 8-year-old boy presented with a pruritic periumbilical rash that he’d had for several months. The rash intensified during the day and improved at night. Some days the rash was much worse than others.

The patient’s mother noted he had recently begun tucking the front of his shirt into his pants. Over-the-counter steroid creams had provided intermittent improvement. He had no significant past medical history and took no other medications.

Examination revealed a 4-cm patch of erythema, scaling, and excoriation without a clear border and no central clearing (FIGURES 1 AND 2). The rest of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

The periumbilical rash

A pruritic rash near the navel, which worsened during the day and improved at night.

FIGURE 2

A closer look

What is your diagnosis?

What therapy would you advise?

Diagnosis: Blue jean button dermatitis

Contact dermatitis secondary to nickel allergy is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to the nickel contained in many blue jean snaps and buttons (FIGURE 3). The rash is typical of contact dermatitis. Macular erythema, sometimes accompanied by papules or vesicles, is also common.

The border is usually ill-defined, and the lesion may become fissured and excoriated. Long-standing cases may become lichenified and scaly. Occasionally, secondary eruptions on flexor surfaces appear.

FIGURE 3

It all lines up

The child’s nickel allergy rash aligns with the snap and button of his blue jeans.

More common among women

Nickel allergy is relatively common; up to 20% of women and 4% of men are affected.1 This discrepancy is thought to be due to the ways in which individuals become sensitized to nickel.

Many women develop a nickel allergy after getting their ears pierced with nickel-containing studs, whereas men tend to be sensitized by an occupational exposure. Nickel allergy appears to be increasing, which may reflect the more common practice of body piercing in general.

How much nickel is too much?

Sensitized patients will react to a metal if more than 1 part in 10,000 is nickel. Metal objects can be tested for nickel content by using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply a few drops of dimethylglyoxime in ammonium hydroxide to the object. If greater than 1 part per 10,000 is nickel, the cotton will turn pink. Recently, Byer and Morrell found that 10% of blue jeans buttons, and more than 50% of belt buckles, test positive.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic periumbilical rash in a child would include psoriasis, scabies, tinea corpus and pityriasis rosea.

Psoriatic lesions

The periumbilical area is a common location for psoriatic lesions. More often involved areas include the scalp and areas of trauma such as the knees, elbows, hands and feet. The lesions of psoriasis tend to have a sharp border and characteristically have silvery white scales associated with them. Psoriasis is often associated with nail abnormalities and arthritis.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies causes an intensely pruritic rash that is classically worse in the finger and toe webs, along the belt line, the groin and axillary regions and, often, periumbilically.

The rash of scabies consists of linearly arranged papules and vesicles due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite’s eggs and feces which are left behind as it burrows through the skin. Excoriation often obscures the typical findings and may be extensive. Treatment of scabies with steroid creams often leads to diffuse erythema and crusting.3

Tinea corpus

Tinea corpus is a dermatophyte infection of the body. These lesions are typically oval and pruritic. Tinea corpus lesions tend to enlarge slowly with a clearly demarcated, slightly raised, erythematous border and central clearing. Satellite lesions may be seen. Applying topical steroids to tinea corpus may result in initial improvement with subsequent flare as the body’s immune response is suppressed.

Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a common pruritic exanthem that can begin as a solitary lesion on the trunk (herald patch). The herald patch is typically an erythematous oval lesion several centimeters in size with a collarette of scales along its border. Typically, within a week numerous other salmon-colored lesions appear on the trunk along Langer’s lines.

The age of peak incidence is during the third decade of life but it does develop in children. Therapy is conservative and targets the control of pruritus.4

Treatment: A simple solution

The mainstay of therapy is avoidance of nickel-containing metals. Buttons can be replaced with plastic ones, or covered with cloth. Patients should not coat buttons with nail polish—it doesn’t work very well.

Stainless steel is a good option for piercings because nickel tends to be tightly bound within the alloy. Topical steroids can be used to speed resolution of the rash and antihistamines may help with pruritus.

Outcome

The patient was placed on a topical steroid (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment). His mother sewed a piece of cloth over the inside of all his pants buttons. The ointment was only given because the mother wanted something that would make the rash go away quickly. Within a week, he was no longer itching and his rash was nearly gone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dean A. Seehusen, MD, MPH Department of Family and Community Medicine, Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, GA 30509 E-mail: dseehusen@msn.com

1. Cerveny KA, Brodell RT. Blue jean button dermatitis. Postgrad Med 2002;112:79-80,83.

2. Byer TT, Morrell DS. Periumbilical contact dermatitis: Blue jeans or belt buckles? Pediatr Dermatol 2004;21:223-226.

3. Flinders DC, DeSchweinitz P. Pediculosis and scabies. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:341-348.

4. Stulberg DL, Wolfrey J. Pityriasis rosea. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:97-92.

An 8-year-old boy presented with a pruritic periumbilical rash that he’d had for several months. The rash intensified during the day and improved at night. Some days the rash was much worse than others.

The patient’s mother noted he had recently begun tucking the front of his shirt into his pants. Over-the-counter steroid creams had provided intermittent improvement. He had no significant past medical history and took no other medications.

Examination revealed a 4-cm patch of erythema, scaling, and excoriation without a clear border and no central clearing (FIGURES 1 AND 2). The rest of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

The periumbilical rash

A pruritic rash near the navel, which worsened during the day and improved at night.

FIGURE 2

A closer look

What is your diagnosis?

What therapy would you advise?

Diagnosis: Blue jean button dermatitis

Contact dermatitis secondary to nickel allergy is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to the nickel contained in many blue jean snaps and buttons (FIGURE 3). The rash is typical of contact dermatitis. Macular erythema, sometimes accompanied by papules or vesicles, is also common.

The border is usually ill-defined, and the lesion may become fissured and excoriated. Long-standing cases may become lichenified and scaly. Occasionally, secondary eruptions on flexor surfaces appear.

FIGURE 3

It all lines up

The child’s nickel allergy rash aligns with the snap and button of his blue jeans.

More common among women

Nickel allergy is relatively common; up to 20% of women and 4% of men are affected.1 This discrepancy is thought to be due to the ways in which individuals become sensitized to nickel.

Many women develop a nickel allergy after getting their ears pierced with nickel-containing studs, whereas men tend to be sensitized by an occupational exposure. Nickel allergy appears to be increasing, which may reflect the more common practice of body piercing in general.

How much nickel is too much?

Sensitized patients will react to a metal if more than 1 part in 10,000 is nickel. Metal objects can be tested for nickel content by using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply a few drops of dimethylglyoxime in ammonium hydroxide to the object. If greater than 1 part per 10,000 is nickel, the cotton will turn pink. Recently, Byer and Morrell found that 10% of blue jeans buttons, and more than 50% of belt buckles, test positive.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic periumbilical rash in a child would include psoriasis, scabies, tinea corpus and pityriasis rosea.

Psoriatic lesions

The periumbilical area is a common location for psoriatic lesions. More often involved areas include the scalp and areas of trauma such as the knees, elbows, hands and feet. The lesions of psoriasis tend to have a sharp border and characteristically have silvery white scales associated with them. Psoriasis is often associated with nail abnormalities and arthritis.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies causes an intensely pruritic rash that is classically worse in the finger and toe webs, along the belt line, the groin and axillary regions and, often, periumbilically.

The rash of scabies consists of linearly arranged papules and vesicles due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite’s eggs and feces which are left behind as it burrows through the skin. Excoriation often obscures the typical findings and may be extensive. Treatment of scabies with steroid creams often leads to diffuse erythema and crusting.3

Tinea corpus

Tinea corpus is a dermatophyte infection of the body. These lesions are typically oval and pruritic. Tinea corpus lesions tend to enlarge slowly with a clearly demarcated, slightly raised, erythematous border and central clearing. Satellite lesions may be seen. Applying topical steroids to tinea corpus may result in initial improvement with subsequent flare as the body’s immune response is suppressed.

Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a common pruritic exanthem that can begin as a solitary lesion on the trunk (herald patch). The herald patch is typically an erythematous oval lesion several centimeters in size with a collarette of scales along its border. Typically, within a week numerous other salmon-colored lesions appear on the trunk along Langer’s lines.

The age of peak incidence is during the third decade of life but it does develop in children. Therapy is conservative and targets the control of pruritus.4

Treatment: A simple solution

The mainstay of therapy is avoidance of nickel-containing metals. Buttons can be replaced with plastic ones, or covered with cloth. Patients should not coat buttons with nail polish—it doesn’t work very well.

Stainless steel is a good option for piercings because nickel tends to be tightly bound within the alloy. Topical steroids can be used to speed resolution of the rash and antihistamines may help with pruritus.

Outcome

The patient was placed on a topical steroid (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment). His mother sewed a piece of cloth over the inside of all his pants buttons. The ointment was only given because the mother wanted something that would make the rash go away quickly. Within a week, he was no longer itching and his rash was nearly gone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dean A. Seehusen, MD, MPH Department of Family and Community Medicine, Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, GA 30509 E-mail: dseehusen@msn.com