User login

Policy in Clinical Practice: Choosing Post-Acute Care in the New Decade

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 70-year-old woman with Medicare insurance and a history of mild dementia and chronic bronchiectasis was hospitalized for acute respiratory failure due to influenza. She was treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 2 days, received mechanical ventilation, and was subsequently extubated and weaned to high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) at 8 liters of oxygen per minute and noninvasive ventilation at bedtime. She had otherwise stable cognition and required no other medical or nursing therapies. For recovery, she was referred to a

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

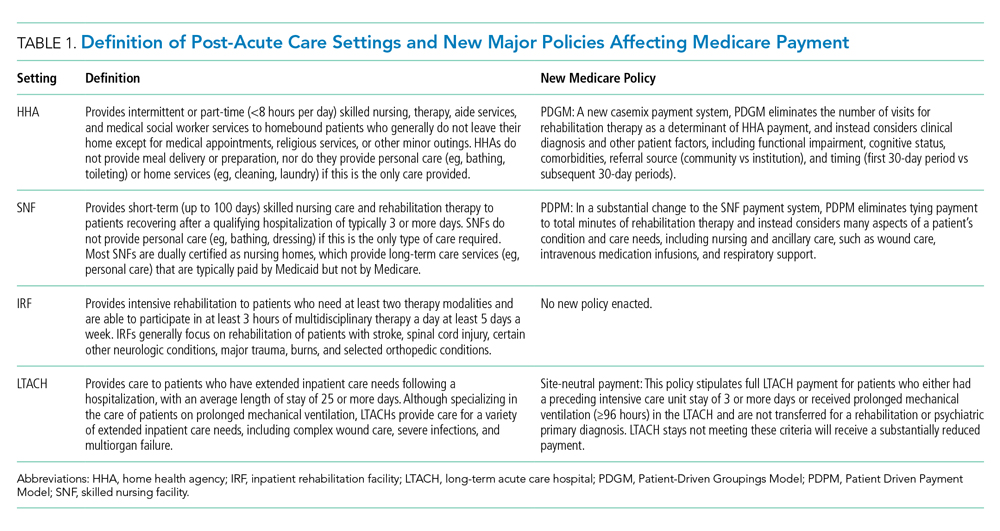

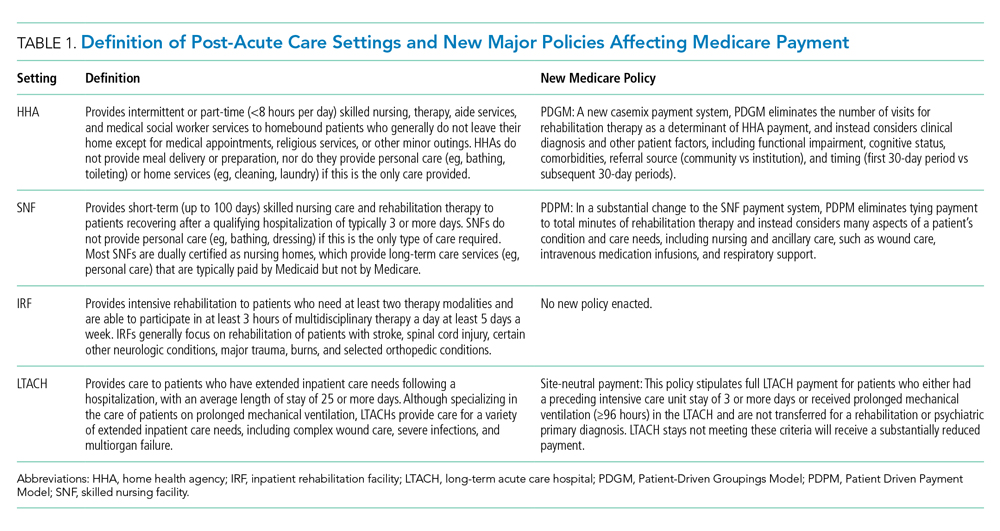

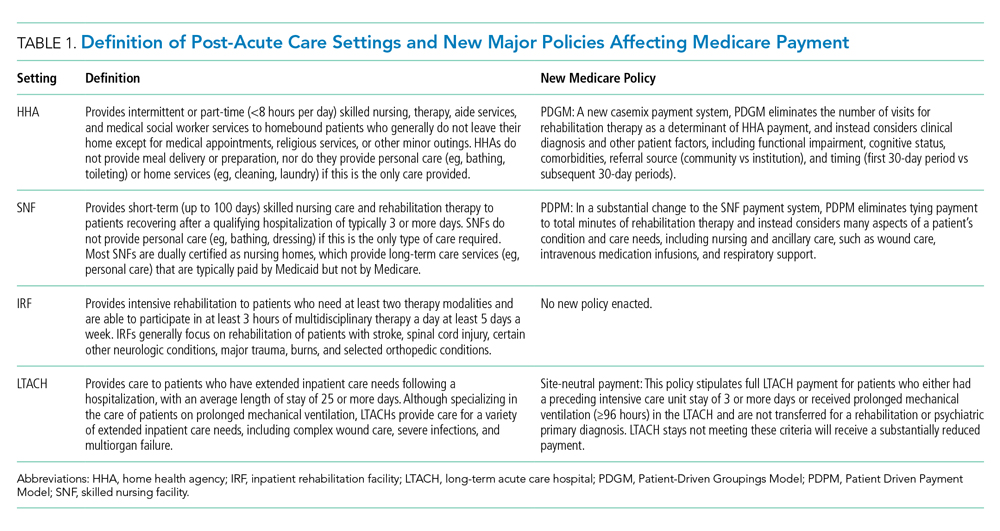

In 2018, 44% of hospitalized patients with fee-for-service Medicare (herein referred to as Medicare) were discharged to PAC, accounting for nearly $60 billion in annual Medicare spending.1 PAC includes four levels of care—home health agencies (HHAs), SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), and LTACHs—which vary in intensity and complexity of the medical, skilled nursing, and rehabilitative services they provide; use separate reimbursement systems; employ different quality metrics; and have different regulatory requirements (Table 1). Because hospitalists care for the majority of these patients and commonly serve in leadership roles for transitions of care and PAC use, PAC policy is important, as it has direct implications on discharge patterns and the quality and nature of patient care after discharge.

HHAs, the most commonly used PAC setting, provide skilled nursing or therapy to homebound beneficiaries.1 HHAs were historically reimbursed a standardized 60-day episode payment based on casemix, which was highly dependent on the number of therapy visits provided, with extremely little contribution from nontherapy services, such as skilled nursing and home health aide visits.2

SNFs, which comprise nearly half of PAC spending, provide short-term skilled nursing and rehabilitative services following hospitalization. SNFs are reimbursed on a per diem basis by Medicare, with reimbursement historically determined by the intensity of the dominant service furnished to the patient—either nursing, ancillary care (which includes medications, supplies/equipment, and diagnostic testing), or rehabilitation.3 Due to strong financial incentives, payment for more than 90% of SNF days was based solely on rehabilitation therapy furnished, with 33% of SNF patients receiving ultra-high rehabilitation (>720 minutes/week),3

IRFs provide intensive rehabilitation to patients who are able to participate in at least 3 hours of multidisciplinary therapy per day.1 IRF admissions are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on the patient’s primary reason for rehabilitation, their age, and their level of functioning and cognition.

LTACHs, the most intensive and expensive PAC setting, care for patients with a range of complex hospital-level care needs, including intravenous (IV) infusions, complex wound care, and respiratory support. Since 2002, the only requirements for LTACHs have been to meet Medicare’s requirements for hospital accreditation and maintain an average length of stay of 25 days for their population.5 LTACH stays are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on diagnosis.

POLICIES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Due to considerable variation in PAC use, with concerns that similar patients can be treated in different PAC settings,6,7 the

For HHAs and SNFs, CMS implemented new payment models to better align payment with patients’ care needs rather than the provision of rehabilitation therapy.1 For SNFs, the Patient

Driven Payment Model (PDPM) was implemented October 1, 2019, and for HHAs, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) was implemented January 1, 2020. These policies increase payment for patients who have nursing or ancillary care needs, such as IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support. For example, the per diem payment to SNFs is projected to increase 10% to 30% for patients needing dialysis, IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support, such as tracheostomy care.8 These policies also increase payment for patients with greater severity and complexity, such as patients with severe cognitive impairment and multimorbidity. Importantly, these policies pay HHAs and SNFs based on patients’ clinical needs and not solely based on the amount of rehabilitation therapy delivered, which could increase both the number and complexity of patients that SNFs accept.

To discourage LTACH use by patients who are unlikely to benefit from this level of care, CMS fully implemented the

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

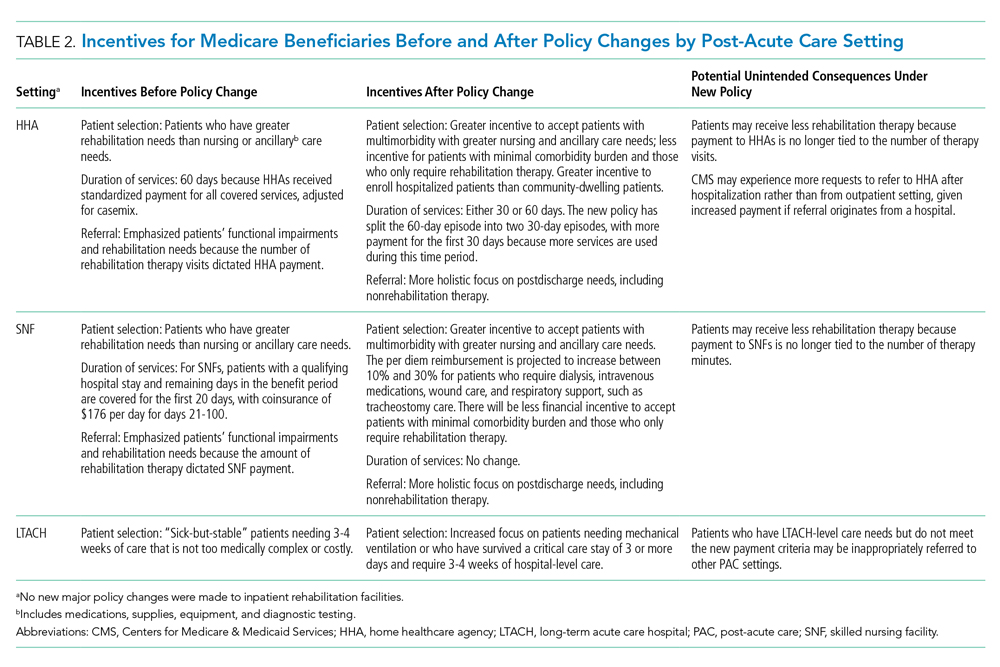

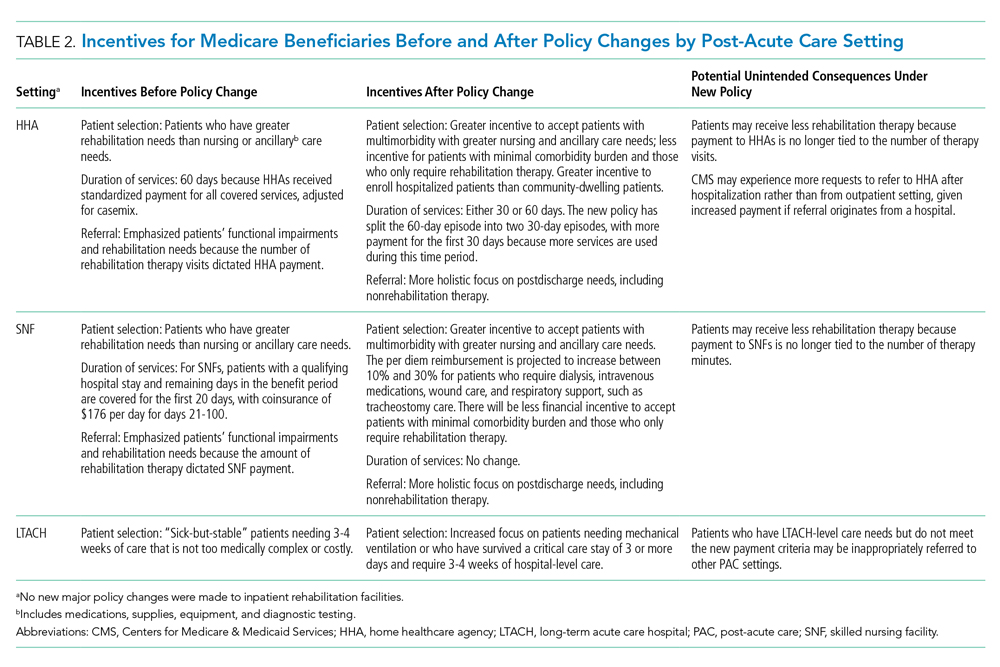

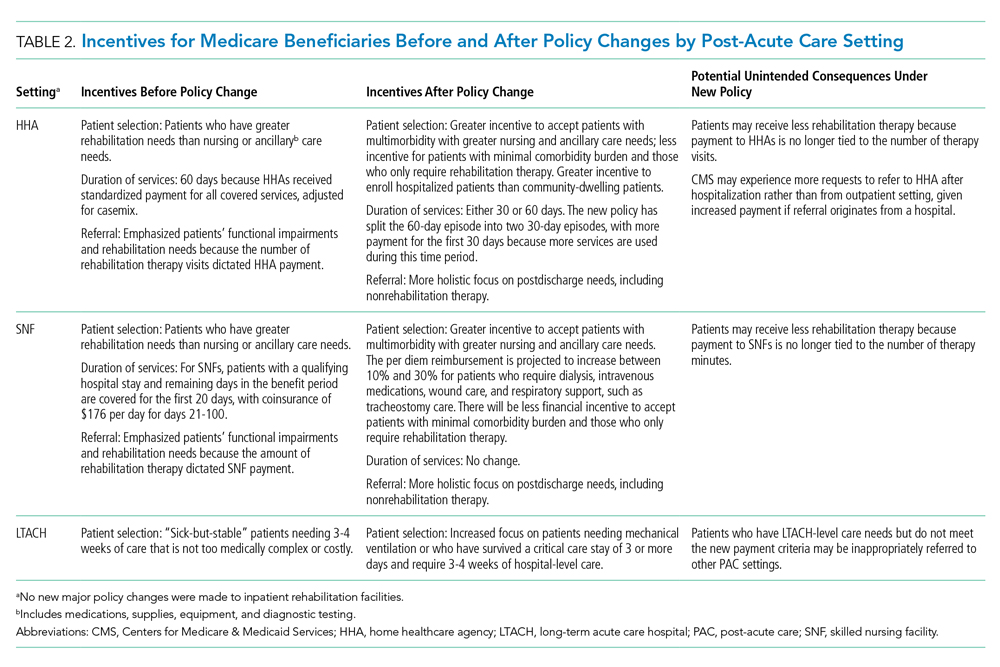

Historically, PAC payment policy has not properly incentivized the appropriate amount of care to be delivered in the appropriate setting.9 The recent HHA, SNF, and LTACH policy changes not only shift the discharge of patients across PAC settings, but also change the amount and type of care that occurs at each PAC site (Table 2). The potential benefit of these new policies is that they will help to align the right level of PAC with patients’ needs by discouraging inappropriate use and unnecessary services.

In terms of broader payment reform, the four PAC settings are still fragmented, with little effort to unify payment, regulation, and quality across the PAC continuum. As required by the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014, we would encourage the adoption of a unified PAC payment system that spans the four settings, with payments based on patient characteristics and needs rather than site of service.12 This type of reform would also harmonize regulation and quality measurement and reward payments across settings. Currently, CMS is standardizing patient assessment data and quality metrics across the four PAC settings. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the transition to a unified PAC payment system is likely several years away.

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

For our patient who was transferred to an LTACH after referrals to SNFs were denied, PAC options now differ following these major PAC policy reforms, and SNF transfer would be an option. This is because SNFs will receive higher payment for providing respiratory support under the PDPM, and LTACHs will receive considerably lower reimbursement because the patient did not have a qualifying ICU stay or require prolonged mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, hospitals participating in accountable care organizations would achieve greater savings, given that LTACHs cost at least three times as much as SNFs for comparable diagnoses.

Instead of referring this patient to a LTACH, the care team (hospitalist, discharge navigator, and case manager) should inform and educate the patient about discharge options to SNFs for weaning from respiratory support. To help patients and caregivers choose a facility, the discharge planning team should provide data about the quality of SNFs (eg, CMS Star Ratings scores) instead of simply providing a list of names and locations.13,14

CONCLUSION

Recent major PAC policy changes will change where hospitals discharge medically complex patients and the services they will receive at these PAC settings. Historically, reduction in PAC use has been a key source for savings in alternative payment models that encourage value over volume, such as accountable care organizations and episode-based (“bundled”) payment models.15 We anticipate these PAC policy changes are a step in the right direction to further enable hospitals to achieve value by more closely aligning PAC incentives with patients’ needs.

1. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2020. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

2. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2020 Home Health Prospective Payment System Rate Update; Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model; Home Heatlh Quality Reporting Requirements; and Home Infusion Therapy Requirements. Fed Regist. 2019;84(217):60478-60646. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 409, 414, 484, and 486. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-11-08/pdf/2019-24026.pdf

3. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) Final Rule for FY 2019, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, and SNF Quality Reporting Program. Fed Regist. 2018;83(153):39162-39290. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 411, 413, and 424. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-08/pdf/2018-16570.pdf

4. Weaver C, Mathews AW, McGinty T. How Medicare rewards copious nursing-home therapy. Wall Street Journal. Updated August 16, 2015. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-medicare-rewards-copious-nursing-home-therapy-1439778701

5. Eskildsen MA. Long-term acute care: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):775-779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01162.x

6. Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1227-1228. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278139

7. Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Xuan L, Miller ME, Goodwin JS, Halm EA. Factors associated with variation in long-term acute care hospital vs skilled nursing facility use among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):399-405. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8467

8. Skilled Nursing Facilities Payment Models Research Technical Report. Acumen; 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/Downloads/SNF_Payment_Models_Research_Technical_Report201704.pdf

9. Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform—beyond the ACA. New Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):689-691. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1315350

10. Span P. A change in Medicare has therapists alarmed. New York Times. November 29, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/29/health/new-old-age-medicare-physical-therapy.html

11. Graham J. Why home health care is suddenly harder to come by for Medicare patients. Kaiser Health News (KHN). February 3, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://khn.org/news/why-home-health-care-is-suddenly-harder-to-come-by-for-medicare-patients/

12. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision. Implementing a unified payment system for post-acute care. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2017:chap 1. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_ch1.pdf?sfvrsn=0

13. Nazir A, Little MO, Arling GW. More than just location: helping patients and families select an appropriate skilled nursing facility. Ann Long Term Care: Clin Care Aging. 2014;22(11):30-34. Published online August 12, 2014. https://www.managedhealthcareconnect.com/articles/more-just-location-helping-patients-and-families-select-appropriate-skilled-nursing

14. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155

15. Barnett ML, Mehrotra A, Grabowski DC. Postacute care—the piggy bank for savings in alternative payment models? New Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):302-303. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901896

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 70-year-old woman with Medicare insurance and a history of mild dementia and chronic bronchiectasis was hospitalized for acute respiratory failure due to influenza. She was treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 2 days, received mechanical ventilation, and was subsequently extubated and weaned to high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) at 8 liters of oxygen per minute and noninvasive ventilation at bedtime. She had otherwise stable cognition and required no other medical or nursing therapies. For recovery, she was referred to a

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

In 2018, 44% of hospitalized patients with fee-for-service Medicare (herein referred to as Medicare) were discharged to PAC, accounting for nearly $60 billion in annual Medicare spending.1 PAC includes four levels of care—home health agencies (HHAs), SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), and LTACHs—which vary in intensity and complexity of the medical, skilled nursing, and rehabilitative services they provide; use separate reimbursement systems; employ different quality metrics; and have different regulatory requirements (Table 1). Because hospitalists care for the majority of these patients and commonly serve in leadership roles for transitions of care and PAC use, PAC policy is important, as it has direct implications on discharge patterns and the quality and nature of patient care after discharge.

HHAs, the most commonly used PAC setting, provide skilled nursing or therapy to homebound beneficiaries.1 HHAs were historically reimbursed a standardized 60-day episode payment based on casemix, which was highly dependent on the number of therapy visits provided, with extremely little contribution from nontherapy services, such as skilled nursing and home health aide visits.2

SNFs, which comprise nearly half of PAC spending, provide short-term skilled nursing and rehabilitative services following hospitalization. SNFs are reimbursed on a per diem basis by Medicare, with reimbursement historically determined by the intensity of the dominant service furnished to the patient—either nursing, ancillary care (which includes medications, supplies/equipment, and diagnostic testing), or rehabilitation.3 Due to strong financial incentives, payment for more than 90% of SNF days was based solely on rehabilitation therapy furnished, with 33% of SNF patients receiving ultra-high rehabilitation (>720 minutes/week),3

IRFs provide intensive rehabilitation to patients who are able to participate in at least 3 hours of multidisciplinary therapy per day.1 IRF admissions are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on the patient’s primary reason for rehabilitation, their age, and their level of functioning and cognition.

LTACHs, the most intensive and expensive PAC setting, care for patients with a range of complex hospital-level care needs, including intravenous (IV) infusions, complex wound care, and respiratory support. Since 2002, the only requirements for LTACHs have been to meet Medicare’s requirements for hospital accreditation and maintain an average length of stay of 25 days for their population.5 LTACH stays are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on diagnosis.

POLICIES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Due to considerable variation in PAC use, with concerns that similar patients can be treated in different PAC settings,6,7 the

For HHAs and SNFs, CMS implemented new payment models to better align payment with patients’ care needs rather than the provision of rehabilitation therapy.1 For SNFs, the Patient

Driven Payment Model (PDPM) was implemented October 1, 2019, and for HHAs, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) was implemented January 1, 2020. These policies increase payment for patients who have nursing or ancillary care needs, such as IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support. For example, the per diem payment to SNFs is projected to increase 10% to 30% for patients needing dialysis, IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support, such as tracheostomy care.8 These policies also increase payment for patients with greater severity and complexity, such as patients with severe cognitive impairment and multimorbidity. Importantly, these policies pay HHAs and SNFs based on patients’ clinical needs and not solely based on the amount of rehabilitation therapy delivered, which could increase both the number and complexity of patients that SNFs accept.

To discourage LTACH use by patients who are unlikely to benefit from this level of care, CMS fully implemented the

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Historically, PAC payment policy has not properly incentivized the appropriate amount of care to be delivered in the appropriate setting.9 The recent HHA, SNF, and LTACH policy changes not only shift the discharge of patients across PAC settings, but also change the amount and type of care that occurs at each PAC site (Table 2). The potential benefit of these new policies is that they will help to align the right level of PAC with patients’ needs by discouraging inappropriate use and unnecessary services.

In terms of broader payment reform, the four PAC settings are still fragmented, with little effort to unify payment, regulation, and quality across the PAC continuum. As required by the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014, we would encourage the adoption of a unified PAC payment system that spans the four settings, with payments based on patient characteristics and needs rather than site of service.12 This type of reform would also harmonize regulation and quality measurement and reward payments across settings. Currently, CMS is standardizing patient assessment data and quality metrics across the four PAC settings. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the transition to a unified PAC payment system is likely several years away.

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

For our patient who was transferred to an LTACH after referrals to SNFs were denied, PAC options now differ following these major PAC policy reforms, and SNF transfer would be an option. This is because SNFs will receive higher payment for providing respiratory support under the PDPM, and LTACHs will receive considerably lower reimbursement because the patient did not have a qualifying ICU stay or require prolonged mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, hospitals participating in accountable care organizations would achieve greater savings, given that LTACHs cost at least three times as much as SNFs for comparable diagnoses.

Instead of referring this patient to a LTACH, the care team (hospitalist, discharge navigator, and case manager) should inform and educate the patient about discharge options to SNFs for weaning from respiratory support. To help patients and caregivers choose a facility, the discharge planning team should provide data about the quality of SNFs (eg, CMS Star Ratings scores) instead of simply providing a list of names and locations.13,14

CONCLUSION

Recent major PAC policy changes will change where hospitals discharge medically complex patients and the services they will receive at these PAC settings. Historically, reduction in PAC use has been a key source for savings in alternative payment models that encourage value over volume, such as accountable care organizations and episode-based (“bundled”) payment models.15 We anticipate these PAC policy changes are a step in the right direction to further enable hospitals to achieve value by more closely aligning PAC incentives with patients’ needs.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 70-year-old woman with Medicare insurance and a history of mild dementia and chronic bronchiectasis was hospitalized for acute respiratory failure due to influenza. She was treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 2 days, received mechanical ventilation, and was subsequently extubated and weaned to high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) at 8 liters of oxygen per minute and noninvasive ventilation at bedtime. She had otherwise stable cognition and required no other medical or nursing therapies. For recovery, she was referred to a

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

In 2018, 44% of hospitalized patients with fee-for-service Medicare (herein referred to as Medicare) were discharged to PAC, accounting for nearly $60 billion in annual Medicare spending.1 PAC includes four levels of care—home health agencies (HHAs), SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), and LTACHs—which vary in intensity and complexity of the medical, skilled nursing, and rehabilitative services they provide; use separate reimbursement systems; employ different quality metrics; and have different regulatory requirements (Table 1). Because hospitalists care for the majority of these patients and commonly serve in leadership roles for transitions of care and PAC use, PAC policy is important, as it has direct implications on discharge patterns and the quality and nature of patient care after discharge.

HHAs, the most commonly used PAC setting, provide skilled nursing or therapy to homebound beneficiaries.1 HHAs were historically reimbursed a standardized 60-day episode payment based on casemix, which was highly dependent on the number of therapy visits provided, with extremely little contribution from nontherapy services, such as skilled nursing and home health aide visits.2

SNFs, which comprise nearly half of PAC spending, provide short-term skilled nursing and rehabilitative services following hospitalization. SNFs are reimbursed on a per diem basis by Medicare, with reimbursement historically determined by the intensity of the dominant service furnished to the patient—either nursing, ancillary care (which includes medications, supplies/equipment, and diagnostic testing), or rehabilitation.3 Due to strong financial incentives, payment for more than 90% of SNF days was based solely on rehabilitation therapy furnished, with 33% of SNF patients receiving ultra-high rehabilitation (>720 minutes/week),3

IRFs provide intensive rehabilitation to patients who are able to participate in at least 3 hours of multidisciplinary therapy per day.1 IRF admissions are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on the patient’s primary reason for rehabilitation, their age, and their level of functioning and cognition.

LTACHs, the most intensive and expensive PAC setting, care for patients with a range of complex hospital-level care needs, including intravenous (IV) infusions, complex wound care, and respiratory support. Since 2002, the only requirements for LTACHs have been to meet Medicare’s requirements for hospital accreditation and maintain an average length of stay of 25 days for their population.5 LTACH stays are paid a bundled rate by Medicare based on diagnosis.

POLICIES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Due to considerable variation in PAC use, with concerns that similar patients can be treated in different PAC settings,6,7 the

For HHAs and SNFs, CMS implemented new payment models to better align payment with patients’ care needs rather than the provision of rehabilitation therapy.1 For SNFs, the Patient

Driven Payment Model (PDPM) was implemented October 1, 2019, and for HHAs, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) was implemented January 1, 2020. These policies increase payment for patients who have nursing or ancillary care needs, such as IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support. For example, the per diem payment to SNFs is projected to increase 10% to 30% for patients needing dialysis, IV medications, wound care, and respiratory support, such as tracheostomy care.8 These policies also increase payment for patients with greater severity and complexity, such as patients with severe cognitive impairment and multimorbidity. Importantly, these policies pay HHAs and SNFs based on patients’ clinical needs and not solely based on the amount of rehabilitation therapy delivered, which could increase both the number and complexity of patients that SNFs accept.

To discourage LTACH use by patients who are unlikely to benefit from this level of care, CMS fully implemented the

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Historically, PAC payment policy has not properly incentivized the appropriate amount of care to be delivered in the appropriate setting.9 The recent HHA, SNF, and LTACH policy changes not only shift the discharge of patients across PAC settings, but also change the amount and type of care that occurs at each PAC site (Table 2). The potential benefit of these new policies is that they will help to align the right level of PAC with patients’ needs by discouraging inappropriate use and unnecessary services.

In terms of broader payment reform, the four PAC settings are still fragmented, with little effort to unify payment, regulation, and quality across the PAC continuum. As required by the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014, we would encourage the adoption of a unified PAC payment system that spans the four settings, with payments based on patient characteristics and needs rather than site of service.12 This type of reform would also harmonize regulation and quality measurement and reward payments across settings. Currently, CMS is standardizing patient assessment data and quality metrics across the four PAC settings. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the transition to a unified PAC payment system is likely several years away.

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

For our patient who was transferred to an LTACH after referrals to SNFs were denied, PAC options now differ following these major PAC policy reforms, and SNF transfer would be an option. This is because SNFs will receive higher payment for providing respiratory support under the PDPM, and LTACHs will receive considerably lower reimbursement because the patient did not have a qualifying ICU stay or require prolonged mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, hospitals participating in accountable care organizations would achieve greater savings, given that LTACHs cost at least three times as much as SNFs for comparable diagnoses.

Instead of referring this patient to a LTACH, the care team (hospitalist, discharge navigator, and case manager) should inform and educate the patient about discharge options to SNFs for weaning from respiratory support. To help patients and caregivers choose a facility, the discharge planning team should provide data about the quality of SNFs (eg, CMS Star Ratings scores) instead of simply providing a list of names and locations.13,14

CONCLUSION

Recent major PAC policy changes will change where hospitals discharge medically complex patients and the services they will receive at these PAC settings. Historically, reduction in PAC use has been a key source for savings in alternative payment models that encourage value over volume, such as accountable care organizations and episode-based (“bundled”) payment models.15 We anticipate these PAC policy changes are a step in the right direction to further enable hospitals to achieve value by more closely aligning PAC incentives with patients’ needs.

1. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2020. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

2. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2020 Home Health Prospective Payment System Rate Update; Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model; Home Heatlh Quality Reporting Requirements; and Home Infusion Therapy Requirements. Fed Regist. 2019;84(217):60478-60646. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 409, 414, 484, and 486. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-11-08/pdf/2019-24026.pdf

3. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) Final Rule for FY 2019, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, and SNF Quality Reporting Program. Fed Regist. 2018;83(153):39162-39290. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 411, 413, and 424. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-08/pdf/2018-16570.pdf

4. Weaver C, Mathews AW, McGinty T. How Medicare rewards copious nursing-home therapy. Wall Street Journal. Updated August 16, 2015. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-medicare-rewards-copious-nursing-home-therapy-1439778701

5. Eskildsen MA. Long-term acute care: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):775-779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01162.x

6. Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1227-1228. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278139

7. Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Xuan L, Miller ME, Goodwin JS, Halm EA. Factors associated with variation in long-term acute care hospital vs skilled nursing facility use among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):399-405. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8467

8. Skilled Nursing Facilities Payment Models Research Technical Report. Acumen; 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/Downloads/SNF_Payment_Models_Research_Technical_Report201704.pdf

9. Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform—beyond the ACA. New Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):689-691. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1315350

10. Span P. A change in Medicare has therapists alarmed. New York Times. November 29, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/29/health/new-old-age-medicare-physical-therapy.html

11. Graham J. Why home health care is suddenly harder to come by for Medicare patients. Kaiser Health News (KHN). February 3, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://khn.org/news/why-home-health-care-is-suddenly-harder-to-come-by-for-medicare-patients/

12. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision. Implementing a unified payment system for post-acute care. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2017:chap 1. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_ch1.pdf?sfvrsn=0

13. Nazir A, Little MO, Arling GW. More than just location: helping patients and families select an appropriate skilled nursing facility. Ann Long Term Care: Clin Care Aging. 2014;22(11):30-34. Published online August 12, 2014. https://www.managedhealthcareconnect.com/articles/more-just-location-helping-patients-and-families-select-appropriate-skilled-nursing

14. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155

15. Barnett ML, Mehrotra A, Grabowski DC. Postacute care—the piggy bank for savings in alternative payment models? New Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):302-303. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901896

1. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2020. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

2. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2020 Home Health Prospective Payment System Rate Update; Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model; Home Heatlh Quality Reporting Requirements; and Home Infusion Therapy Requirements. Fed Regist. 2019;84(217):60478-60646. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 409, 414, 484, and 486. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-11-08/pdf/2019-24026.pdf

3. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) Final Rule for FY 2019, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, and SNF Quality Reporting Program. Fed Regist. 2018;83(153):39162-39290. To be codified at 42 CFR Parts 411, 413, and 424. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-08/pdf/2018-16570.pdf

4. Weaver C, Mathews AW, McGinty T. How Medicare rewards copious nursing-home therapy. Wall Street Journal. Updated August 16, 2015. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-medicare-rewards-copious-nursing-home-therapy-1439778701

5. Eskildsen MA. Long-term acute care: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):775-779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01162.x

6. Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1227-1228. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278139

7. Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Xuan L, Miller ME, Goodwin JS, Halm EA. Factors associated with variation in long-term acute care hospital vs skilled nursing facility use among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):399-405. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8467

8. Skilled Nursing Facilities Payment Models Research Technical Report. Acumen; 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/Downloads/SNF_Payment_Models_Research_Technical_Report201704.pdf

9. Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform—beyond the ACA. New Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):689-691. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1315350

10. Span P. A change in Medicare has therapists alarmed. New York Times. November 29, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/29/health/new-old-age-medicare-physical-therapy.html

11. Graham J. Why home health care is suddenly harder to come by for Medicare patients. Kaiser Health News (KHN). February 3, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://khn.org/news/why-home-health-care-is-suddenly-harder-to-come-by-for-medicare-patients/

12. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision. Implementing a unified payment system for post-acute care. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Medicare Payment Advisory Commision; 2017:chap 1. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_ch1.pdf?sfvrsn=0

13. Nazir A, Little MO, Arling GW. More than just location: helping patients and families select an appropriate skilled nursing facility. Ann Long Term Care: Clin Care Aging. 2014;22(11):30-34. Published online August 12, 2014. https://www.managedhealthcareconnect.com/articles/more-just-location-helping-patients-and-families-select-appropriate-skilled-nursing

14. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155

15. Barnett ML, Mehrotra A, Grabowski DC. Postacute care—the piggy bank for savings in alternative payment models? New Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):302-303. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901896

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine