User login

Inpatient Staffing in Pediatric Programs

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

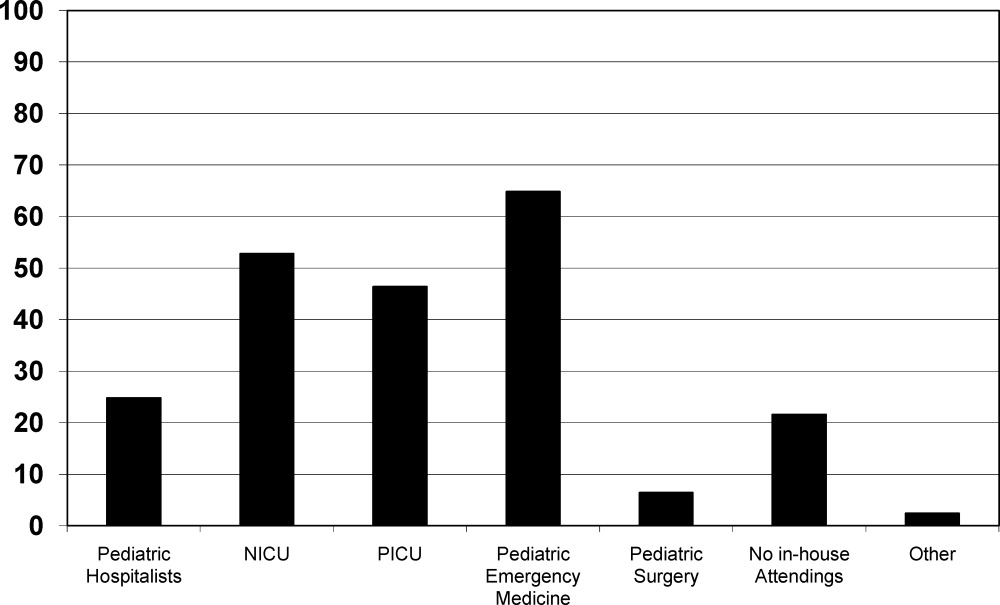

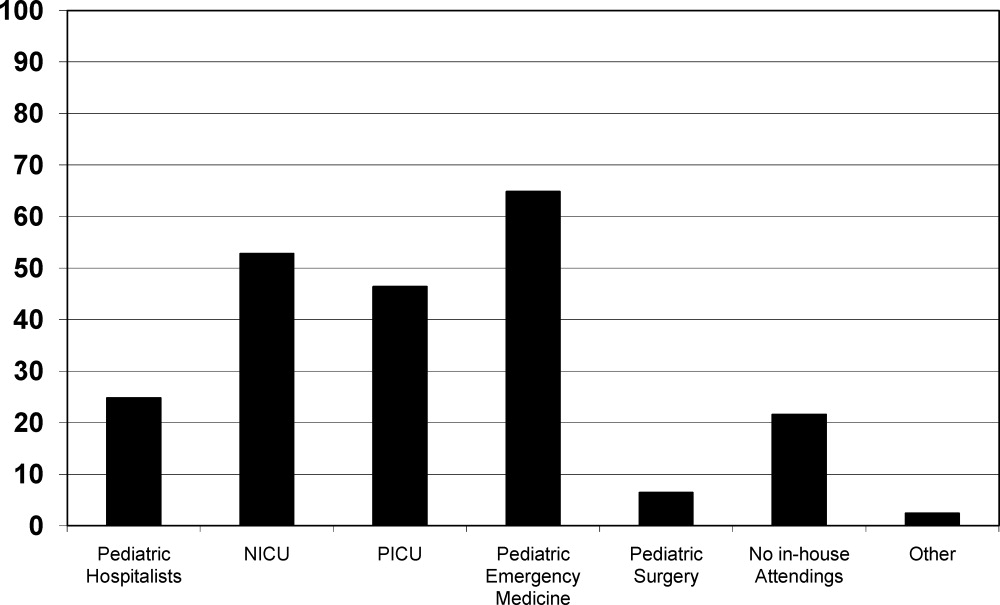

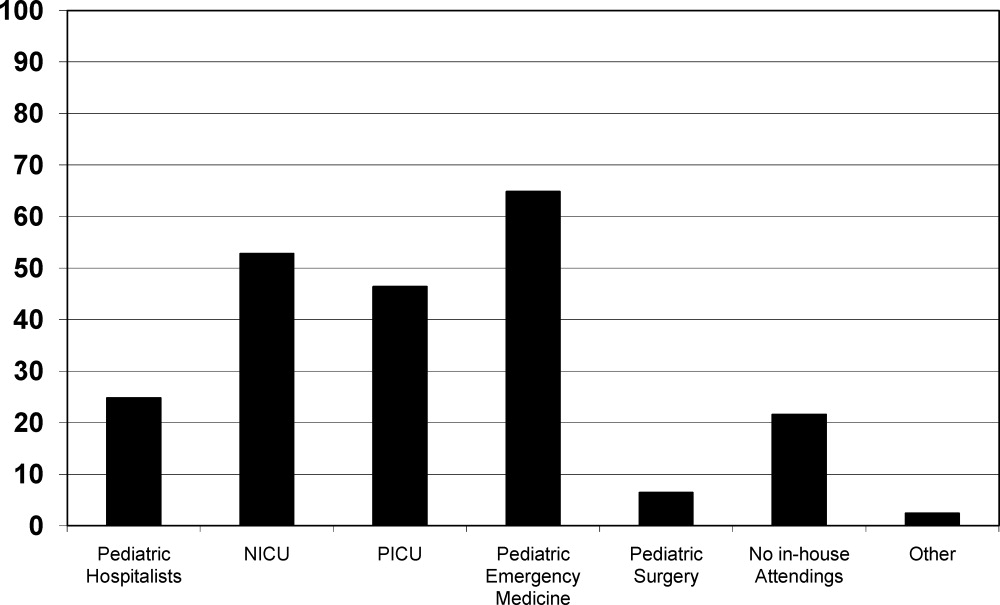

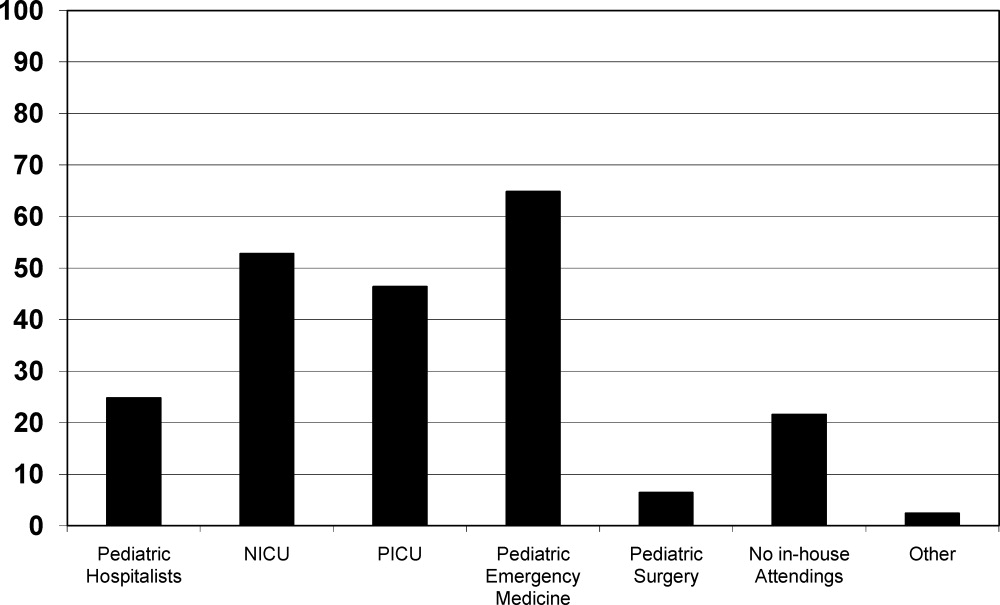

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Hospitalists' Influences

The number of pediatric hospitalists (PH) in the United States is increasing rapidly. The membership of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine has grown to 880 (7/10, AAP Section on Hospital Medicine), and there over 10,000 members of the Society of Hospital Medicine of which an estimated 5% care for children (7/10, Society of Hospital Medicine). Little is known about the educational contributions of pediatric hospitalists, residents' perceptions of hospitalists' roles, or how hospitalists may influence residents' eventual career plans even though 89% of pediatric hospitalists report they serve as teaching attendings.1 Teaching by hospitalists is well received and valued by residents, but, to date, all such data are from single institution studies of individual hospitalist programs.27 Less is known regarding what residents perceive about the differences in patient care provided by hospitalists as compared with traditional pediatric teaching attendings. There is a paucity of information about the level of interest of current pediatric residents in becoming hospitalists, including how many plan such a career, reasons why residents might prefer to become hospitalists, and their perceptions of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) careers as either long or short term. In addition, the effects of new residency graduates going into Hospital Medicine on the overall pediatric workforce, and how the availability of Hospital Medicine careers affects the choice of practice in Primary Care Pediatrics have not been examined.

We surveyed a national, randomly selected representative sample of pediatric residents to determine their level of exposure to hospitalist attending physicians during training. We asked the resident cohort about their educational experiences with hospitalists, patient care provided by hospitalists on their team, and career plans regarding becoming a hospitalist, including perceived needs for different or additional training. We obtained further information about reasons why hospitalist positions were appealing and about the current relationship between careers in Pediatric Hospital Medicine and Primary Care. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of how pediatric hospitalists might influence residents in the domains of education, patient care, and career planning.

METHODS

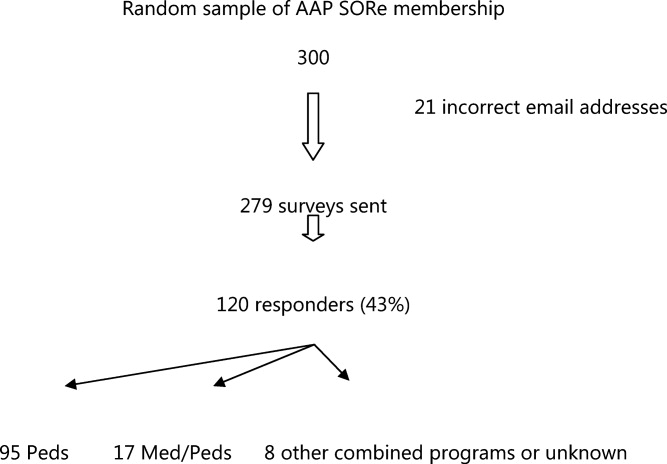

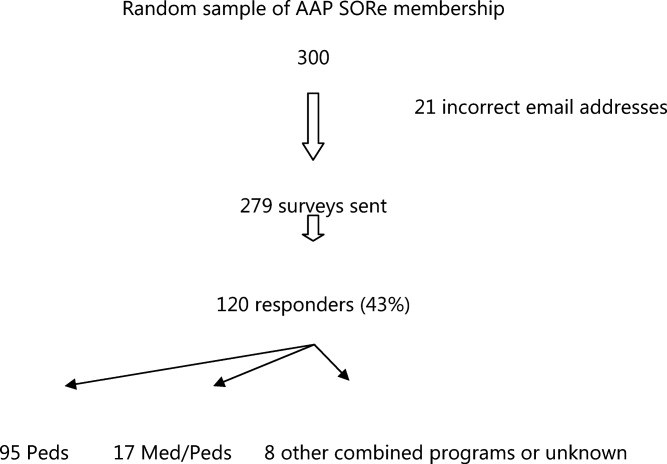

We conducted a survey of randomly selected pediatric residents from the AAP membership database. The selection was done by random generation by the AAP Department of Research from the membership database, in the same way members are selected for the annual Survey of Fellows and the annual pediatric level 3 (PL3) survey. Permission was obtained from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Residents (AAP SORe) to survey a selection of US pediatric residents in June 2007. The full sample of US pediatric residents included 9569 residents. The AAP SORe had 7694 e‐mail addresses from which the AAP Department of Research generated a random sample of 300 for our use, including Medicine‐Pediatric, Pediatric, and Pediatric Chief residents. One of the researchers (A.H.) sent an e‐mail with the title $200 AAP Career Raffle Survey containing a link to a SurveyMonkey survey (see Supporting Appendix AQuestionnaire in the online version of this article) and offering incentivized participation with a raffle. The need for informed consent was waived, as consent was implied by participation in the survey. The survey was taken anonymously by connecting through the link, and when it was completed, residents were asked to separately e‐mail a Section on Hospital Medicine address if they wished to participate in the raffle. Their raffle request was not linked to their survey results in any way. The $200 was supplied by the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine. The survey was sent 3 times. We analyzed responses with descriptive statistics. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Concord Hospital in Concord, New Hampshire.

RESULTS

The respondents are described in Figure 1 and Table 1. For their exposure to PHM, 54% (73 of 111) reported PH attendings in medical school; 90% (75 of 83) did have or will have PH attendings during residency, with no significant variation by program size (small, medium, large, or extra large). The degree of exposure was not asked. To learn about PHM, 47% (46 of 97 respondents) asked a PH in their program, while 28% (27 of 99) visited the AAP web site. Sixty‐eight percent (73 of 108) felt familiar or very familiar with PHM.

| % | Absolute Response Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Training year | ||

| PL1 | 47.5 | 57 |

| PL2 | 35 | 42 |

| PL3 | 9 | 11 |

| PL4 | 1 | 1 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31.5 | 38 |

| Female | 61 | 73 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Specialty | ||

| Pediatrics | 79 | 95 |

| Med/Peds | 14 | 17 |

| Other (Pediatric combination residencies) | 4 | 5 |

| Skipped question | 3 | 3 |

| Program size | ||

| Less than 15 residents in program | 11 | 12 |

| 16‐30 | 38.5 | 42 |

| 31‐45 | 22.9 | 25 |

| Greater than 45 | 27.5 | 30 |

| Skipped question | 9.1 | 11 |

Table 2 summarizes the respondents' perception of PHM. They report a positive opinion of the field and overwhelmingly feel that PHM is a growing/developing field. Almost none feel PHM will not survive. A small percentage (10%, 28 of 99) felt there was no difference between PH and residents, with 25% (25 of 99) feeling some ambiguity about whether the PH role differs from that of a resident. Many (35 of 99) did not disagree that there is little difference between PH and resident positions, although most did. Sixty percent (59 of 99) agreed or strongly agreed that a PH position would be a good job for the short‐term. Forty‐seven percent (46 of 99) agreed in some form that PHM gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position. Given the choice of PHM as a long‐term opportunity, short‐term opportunity, either or not sure: 21% (21 of 98) saw PHM as a short‐term option only; 26% (25 of 98) saw PHM as a long‐term career only; 49% (48 of 98) saw it as either a short‐term option or long‐term career. Most (65%, 64 of 99) believed PH were better than primary care providers at caring for complex inpatients, but only 28% (28 of 99) thought PH provided better care for routine admissions. Most (82%, 81 of 99) agreed in some form that working with pediatric hospitalists enhances a resident's education.

| Strongly/Somewhat Disagree | Neither Disagree or Agree | Somewhat/Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I think it is a great field | 2% (9/99) | 15% (15/99) | 83% (82/99) |

| It's a good job for the short‐term | 13% (13/99) | 27% (27/99) | 60% (59/99) |

| It gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position | 20% (20/99) | 33% (33/99) | 47% (46/99) |

| It's a growing/developing field | 1% (1/99) | 8% (8/99) | 91% (90/99) |

| It's a field that won't survive | 86% (85/99) | 13% (13/99) | 1% (1/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of complex inpatients than are primary care physicians | 20% (20/99) | 15% (15/99) | 65% (64/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of routine patient admissions than are primary care physicians | 39% (39/99) | 32% (32/99) | 28% (28/99) |

| There is little difference between hospitalist and resident positions | 65% (64/99) | 25% (25/99) | 10% (10/99) |

| Working with hospitalists enhances a residents education | 2% (2/99) | 16% (16/99) | 82% (81/99) |

On a 5‐point scale ranging from would definitely not include to might or might not include to would definitely include, the majority of respondents felt a PHM job would definitely include Pediatric Wards (86%, 84 of 98) and Inpatient Consultant for Specialists (54%, 52 of 97). Only 47% (46/97) felt the responsibilities would probably or definitely include Medical Student and Resident Education (47%, 46 of 97). The respondents were less certain (might or might not response) if PHM should include Normal Newborn Nursery (37%, 36 of 98), Delivery Room (42%, 41 of 98), Intensive Care Nursery (35%, 34 of 98), ED/Urgent Care (34%, 33 of 98), or Research (50%, 49 of 98). A majority of respondents felt PHM unlikely to include, or felt the job might not or might include: Outpatient Clinics (77%, 75 of 98), Outpatient Consults (81%, 79 of 98), and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit work (70%, 68 of 98).

Of categorical pediatric trainees answering the question, 35% (28 of 80) are considering a PHM career. Immediately post‐residency, 30% (24 of 80) of categorical trainees plan to enter Primary Care (PC), 4% (3 of 80) plan on PHM, and 3% (2 of 80) plan to pursue PH fellowship.

Of all respondents given the choice of whether a factor plays no role, limited role, or strong role in considering a career in PHM: flexible hours (96%, 94 of 98), opportunities to participate in education (97%, 95 of 98), and better salary than PC (94%, 91 of 97) would influence their decision to choose PHM. For 49% (48 of 98), ability to do the job without fellowship would play a strong role in choosing a career in PHM.

Forty‐five percent (44 of 97) support training in addition to residency; 16.5% (16 of 97) are against it; the remaining 38% (37 of 97) are unsure. Three percent (3 of 98) thought 3‐year fellowship best, while 28% (27 of 98) preferred 2‐year fellowship; 29% (28 of 98) would like a hospitalist‐track residency; 28% (27 of 98) believe standard residency sufficient; and 4% (4 of 98) felt a chief year adequate. If they were to pursue PHM, 31% (30 of 98) would enter PH fellowship, 34% (33 of 98) would not, and 36% (35 of 98) were unsure.

On a 5‐point scale, respondents were asked about barriers identified to choosing a career in PHM: 28% (27 of 96) agreed or strongly agreed that not feeling well‐enough trained was a barrier to entering the field; 42% (40 of 96) were agreed in some form that they were unsure of what training they needed; 39% (37 of 95) were unsure about where positions are available. Seven percent (7 of 98) of respondents were less likely to choose to practice Primary Care (PC) pediatrics because of hospitalists. Of respondents choosing PC, 59% (34 of 58) prefer or must have PH to work within their future practices, while 12% (7 of 58) prefer not to, or definitely do not want to, work with PH.

DISCUSSION

In 2006, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) General Pediatrics Career Survey found that 1% of first‐time applicants were taking a hospitalist position.8 In 2007, this number grew to 3% choosing a position in Pediatric Hospital Medicine.9, 10 The 2009‐2010 survey data found that 7.6% of first‐time applicants would be taking a job as hospitalist as of July 1.11 Our data suggest this number will continue to grow over the next few years. The growth of PHM has prompted an in‐depth look at the field by the ABP.1, 12, 13 PHM programs appear to have become part of the fabric of pediatric care, with the majority of hospitals with PHM programs planning to continue the programs despite the need to pay for value‐added by hospitalists beyond revenue received for their direct clinical service.13 Looking forward, when the Institute of Medicine recommendations to further restrict resident work hours to 16 hour shifts are implemented, many programs plan on increasing their PHM programs.14, 15 Therefore, residents' views of a career in PHM are important, as they give perspective on attitudes of those who might be, or interact with, hospitalists in the future, and should impact training programs for residents regardless of their interest in a career in PHM.

Our national data support local, large institution studies that hospitalists are positively impacting education.27 However, this study suggests that this is not only a local or large academic center phenomenon, but a national trend towards providing a different and positive education experience for pediatric residents. This mirrors the opinion of the majority of residency and clerkship directors who feel that hospitalists are more accessible to trainees than traditional attendings.12 Training programs should consider this impact when selecting attending hospitalists and supporting their roles as mentors and educators.

As residents finish their training and seek positions as pediatric hospitalists, programs need to be aware that a significant percentage of residents in our survey see PHM as a short‐term career option and/or fail to see a difference between a PH job and their own. Program Directors also need to be aware of the breadth of PHM practice which can include areas our respondents felt were less likely to be part of PHM, such as other inpatient areas and the expectation of research.

While 1 option to address some of these issues is fellowship training, this is not a simple decision. PHM needs to determine if fellowship is truly the best option for future hospitalists and, if so, what the fellowship should look like in terms of duration and scope. While the needs of optimal training should be paramount, resident preferences to not commit to an additional 3 years of training must be considered. Many residents fail to see a difference between the role of PH and their own role during training, and feel that the current format of residency training is all the preparation needed to step into a career as a PH. This demonstrates a clear gap between resident perceptions of PHM and the accepted definition of a hospitalist,16 which reaches far beyond direct inpatient care. While The Core Competencies for Pediatric Hospital Medicine17 address a number of these areas, neither trainees nor hospitalists themselves have fully integrated these into their practice. PH must recognize and prepare for their position as mentors and role models to residents. This responsibility should differentiate PH role from that of a resident, demonstrating roles PH play in policy making, patient safety and quality initiatives, in administration, and in providing advanced thinking in direct patient care. Finally, PH and their employers must work to build programs that present PHM as a long‐term career option for residents.

There is a significant impact on the field if those who enter it see it only as something to do while waiting for a position elsewhere. While some of these new‐careerists may stay with the field once they have tried it and become significant contributors, inherent in these answers are the issues of turnover and lack of senior experience many Hospital Medicine programs currently face. Additionally, and outside the scope of this survey, it is unclear what those next positions are and how a brief experience as a hospitalist might impact their future practice.

It is a significant change that residents entering a Primary Care career expect to work with pediatric hospitalists and, in general, see this as a benefit and necessity. The 2007 American Board of Pediatrics' survey found that 27% of respondents planned a career in General Pediatrics with little or no inpatient care.10 Hospitalists of the near future will likely face a dichotomy of needs between primary care providers who trained before, and those who trained after, the existence of hospitalists. Hospitalists will need to understand and address the ongoing needs of both of these groups in order to adequately serve them and their patient‐bases.

Limitations of our study include our small sample size, with a response rate of 43% at best (individual question response rate varied). Though the group was nationally representative, it was skewed towards first year respondents, likely due to the time of year in which it was distributed. There is likely some bias due to the low response rate, in that those more interested in careers as hospitalists might be more likely to respond. This might potentially inflate the percentages of those who state they are interested in being a hospitalist. In addition, given that the last round of the survey went out at the very end of the academic year, graduating residents had a lower response rate.

We were unable to compare opinions across unexposed and exposed residents because only 6.5% reported knowing nothing about the field, and only 2 respondents had not had any exposure to pediatric hospitalists to date. Given that most residencies have PHM services,12 this distinction is unlikely to be significant. In looking at training desires, we did not compare them to residents considering entering other fields of medicine. It may be true that residents considering other fellowships do not desire to do 3 years of fellowship training. That being said, it in no way diminishes the implication that 3‐year fellowships for PHM may not be the right answer for future training.

Strengths of the study include that it is, to our knowledge, the first national study of a group of residents regarding exposure to, and career plans as related to, PH. In addition, the group is gender‐balanced, and represents residents from a range of training sites (urban, suburban, rural) and program sizes. This study offers important information that must be considered in the further development of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

CONCLUSION

This was the first national study of residents regarding Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Almost all residents are exposed to PH during their training, though a gap of no exposure still exists. More work needs to be done to improve the perception of PHM as a viable long‐term career. Nevertheless, PHM has become a career consideration for trainees. Nearly half agreed that some type of specialized training would be helpful. This information should impact on the development of PHM training programs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine for raffle funding, and Texas Children's Hospital and Dr Yong Han for use of SurveyMonkey and assistance with survey set‐up. Also thanks to Dr Vincent Chang for his guidance and review.

- ,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment.Pediatrics.2007;120(1):33–39.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156(9):877–883.

- ,,.Establishing a pediatric hospitalist program at an academic medical center.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2000;39(4):221–227.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2001;40(12):653–660.

- .Employing hospitalists to improve residents' inpatient learning.Acad Med.2001;76(5):556.

- ,,,,,.Community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):34–38.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2006 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed on January 15, 2008.

- ,,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.General pediatrics resident perspectives on training decisions and career choice.Pediatrics.2009;123(1 suppl):S26–S30.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2007 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 10,2009.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2009–2010 Workforce Data. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 20,2010.

- ,,.Hospitalists' involvement in pediatrics training: perspectives from pediatric residency program and clerkship directors.Acad Med.2009;84(11):1617–1621.

- ,,.Assessing the value of pediatric hospitalist programs: the perspective of hospital leaders.Acad Pediatr.2009;9(3):192–196.

- ,,,.Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist.J Hosp Med.2011;6(in press).

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/. Accessed December 15, 2010.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Hospitalist_Definition5:i–iv. doi://10.1002/jhm.776. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed on May 11, 2011.