User login

Staffing Following Residency Work Hours

Long work hours with abnormal schedules and extended on‐call periods are common for physicians. Prior to resident work‐hour restrictions, studies showed that sleep‐deprived residents were at increased risk for making errors with decreased decision‐making abilities.[1, 2] Resident work‐hour restrictions and increased attending supervision regulations were initially implemented in 1989 in New York due to concerns for patient safety.[3] In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted this 80‐hour work week standard nationally and restricted residents to a maximum of 30 hours of continuous clinical responsibilities.[4] Due to concern that residents working extending periods of time were at risk for making serious medical errors,[5, 6, 7] the ACGME mandated additional resident work‐hour restrictions in July 2011.8 These changes reduced the maximum hours of continuous clinical responsibilities from 30 to 16 hours for interns, and 28 hours for upper‐level residents, including 4 hours for transition of patient care. Continuous on‐site supervision by attending physicians is not mandated, but programs had to accommodate for the increased emphasis on attending services and supervision of residents, especially at night.[6, 8] Our previous study in 2010, prior to the implementation of new resident work hours, showed 84% of pediatric residency programs had pediatric hospitalists. Of those, 24% had 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage, 22% of pediatric residency programs had no in‐house attendings at night, and 31% of programs at that time planned on adding 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage within the next 5 years if further resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented.[9]

The objective of this study was to determine how inpatient staffing of teaching services within pediatric residency programs has changed following this recent transition of additional resident work hours. We also sought to define current attending physician staffing and explore attending physicians' overnight responsibilities following new ACGME standards, specifically looking at the role of pediatric hospitalists.

METHODS

We developed a Web‐based electronic survey consisting of 23 questions. Many of these questions were multiple choice or numerical values with the option to comment. The survey gathered data on the demographics of pediatric residency programs including: the number of residents in each program, patient admission caps (the total number of patients the resident team can admit overnight), and the use of resident night floats (a resident team working the overnight shift, admitting and cross‐covering patients who will be handed over to a day team in the morning).

We also examined the number of pediatric providers at night, the use of pediatric hospitalists, and specifically the use of attendings in‐house at night and their overnight responsibilities.

The survey was first pilot tested by pediatric hospitalists for face validity. It was reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent to 198 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in May 2012. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or designating someone else to complete it. We sent 2 e‐mail reminders via the listserve with individual e‐mail reminders to nonresponding programs. We sent follow‐up e‐mails and phone calls to programs with current night float systems to clarify their use of resident night float prior to implementation of new work‐hour restrictions. Duplicate responses from a program were removed by initially removing the 1 with incomplete data. If both responses were complete, we removed the second response. We analyzed the use of resident night float systems and admission caps, as well as the use of attending physicians in‐house at night, using a z‐score and [2] test.

The institutional review board of the Indiana University School of Medicine reviewed this study.

RESULTS

Out of 198 pediatric ACGME programs contacted, 152 responses were received, which is a 77% response rate. This represented 7828 pediatric residents, or 79% of total US pediatric residents. Average program size was 52 residents (range, 6168 residents; median, 41). This average program size was similar to the ACGME average program size of 50 residents. Sorting our response rate by program size, all 58 large ACGME programs responded (programs with over 50 residents). Eighty‐four percent (57 programs) of medium‐sized programs responded (programs with 3050 residents). Fifty‐one percent (37 programs) of small programs responded (programs with <30 residents).

Changes in Resident Staffing

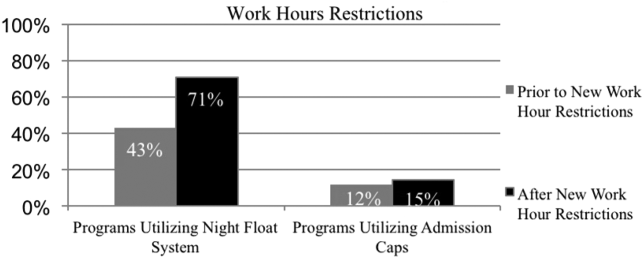

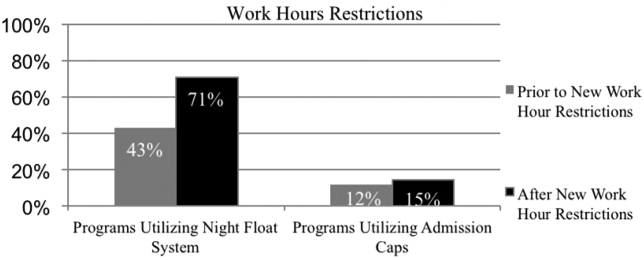

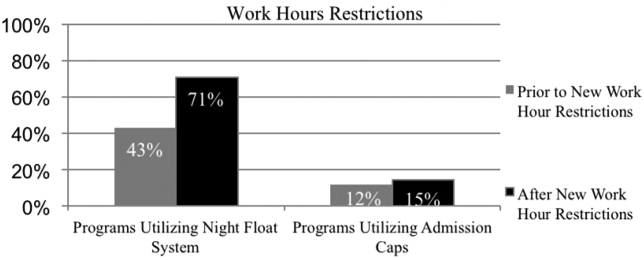

Residency programs utilizing night float systems increased from 43% before to 71% after new work hours were implemented (P<0.0001). Overall use of resident admission caps did not significantly change (12%14.5%, P=0.52) (Figure 1).

Changes in Attending Physicians In‐House at Night

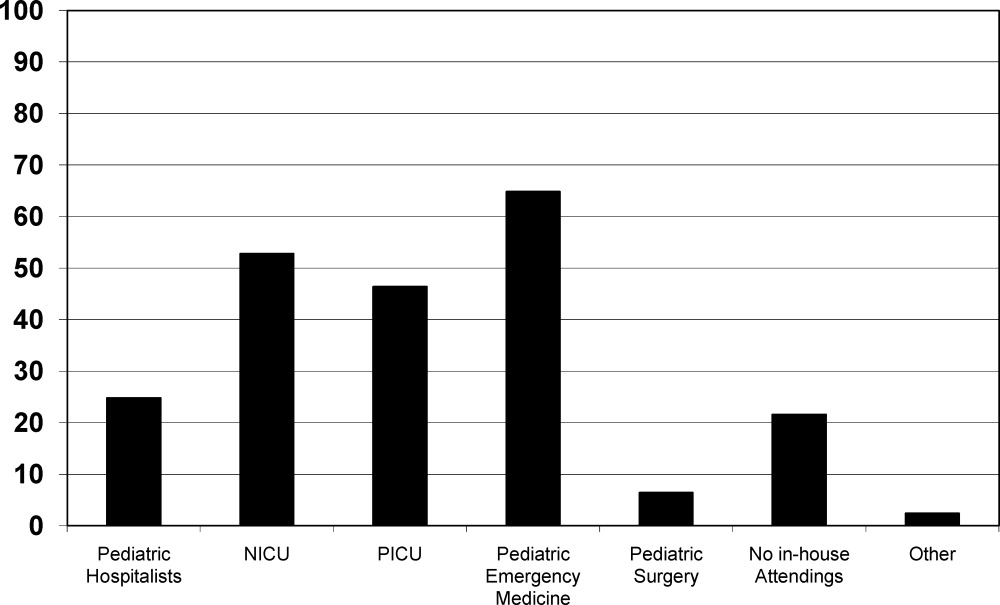

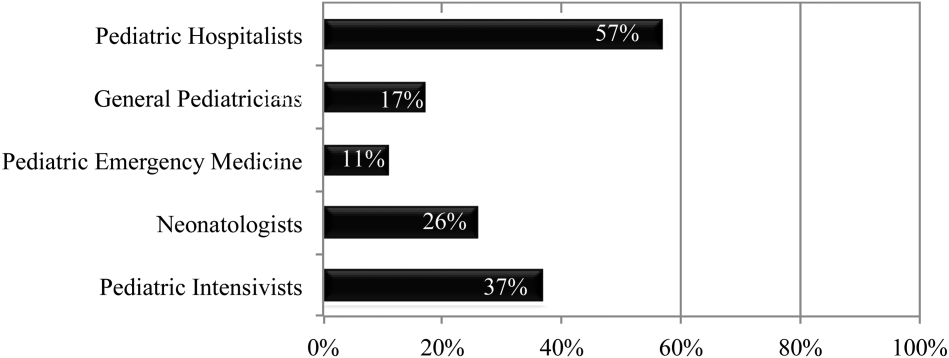

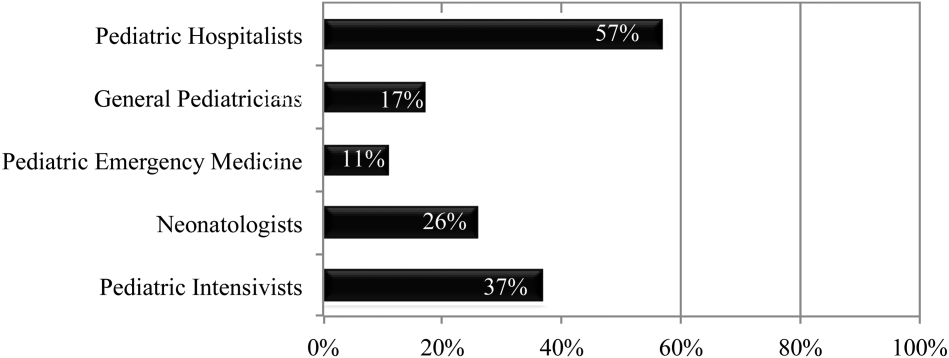

Following implementation of new resident work‐hour restrictions, 23% of programs increased the number of attending physicians in‐house at night. Of these programs, 57% (20 programs) increased the number of pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night, whereas 37% increased the number of pediatric intensive care unit attendings (Figure 2). When asked the reason for increased attending physician presence in‐house, 71% of programs attributed this change to increased resident work‐hour restrictions, and 37% attributed it to increased patient census. Other common reasons cited included increased patient acuity as well as improved resident supervision and education.

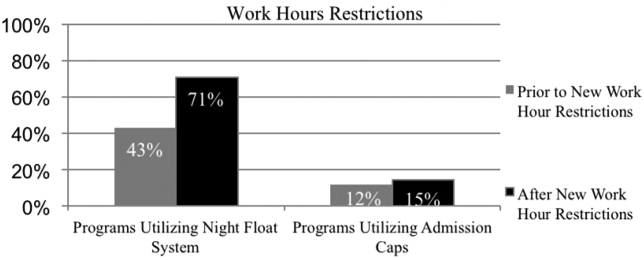

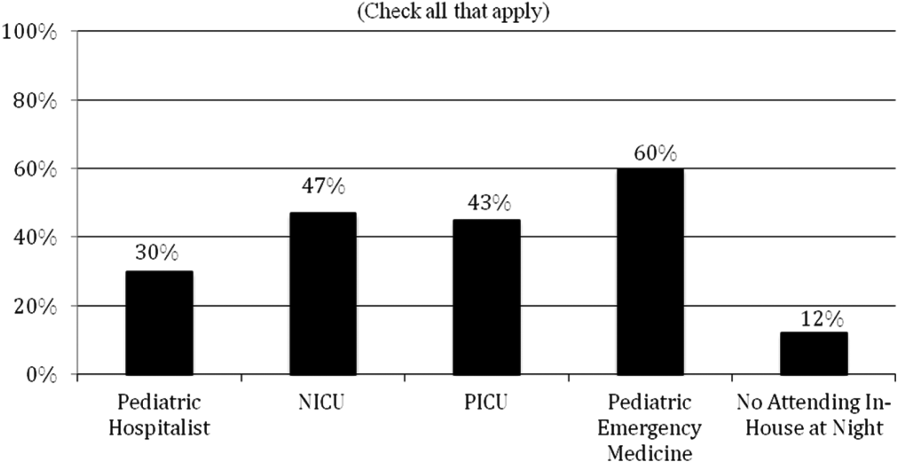

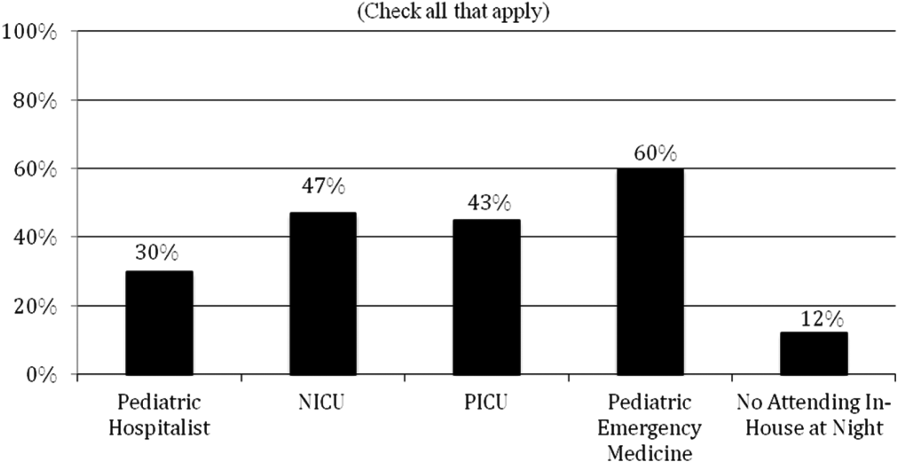

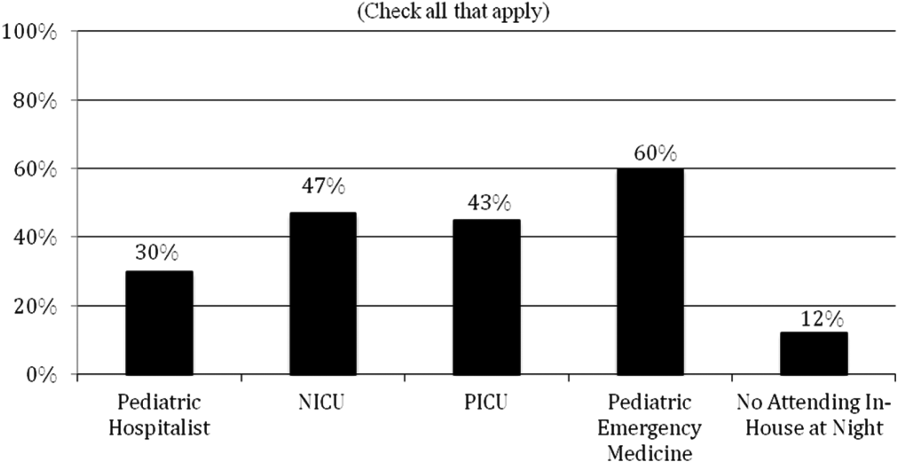

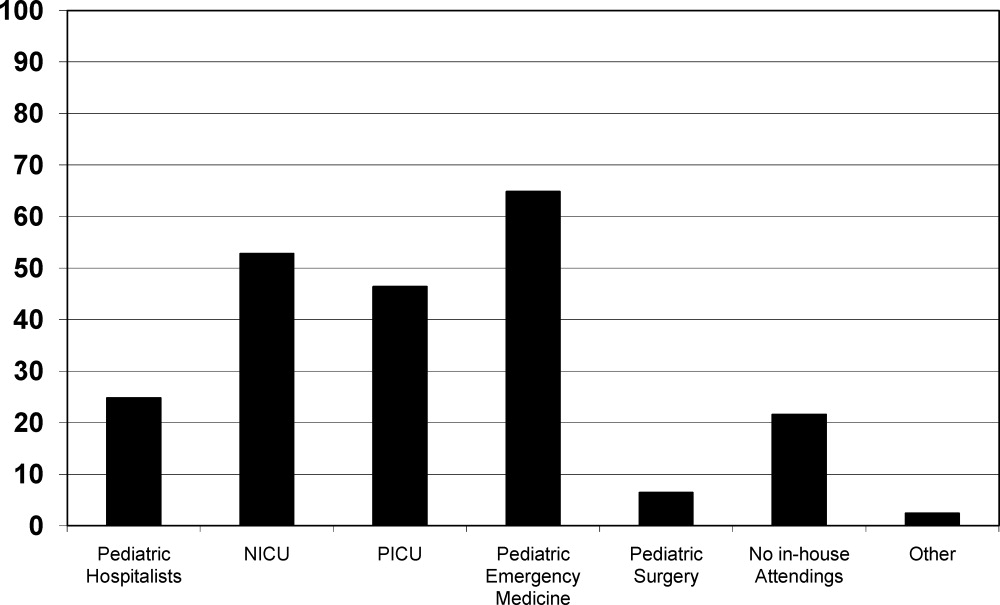

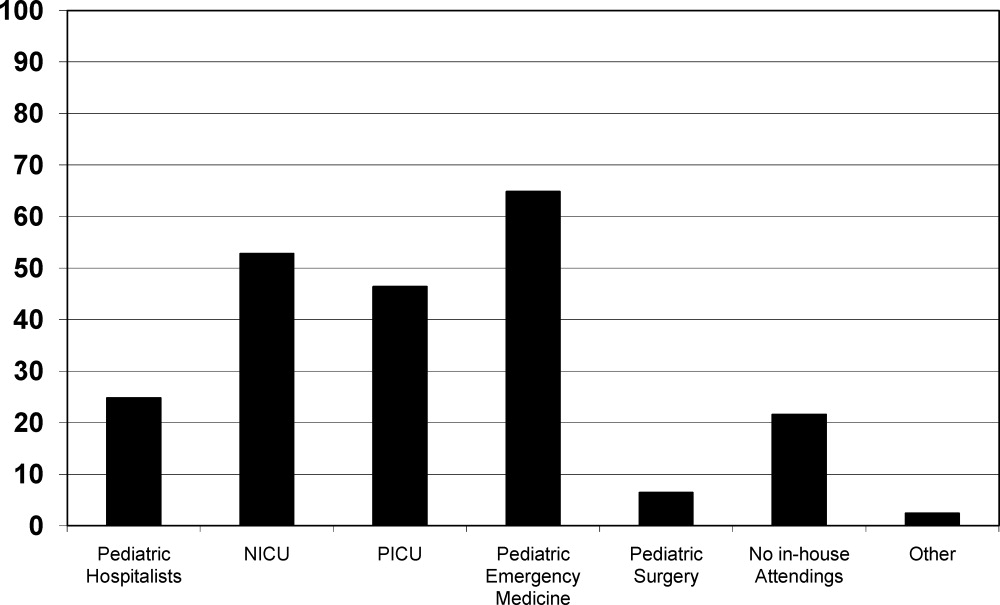

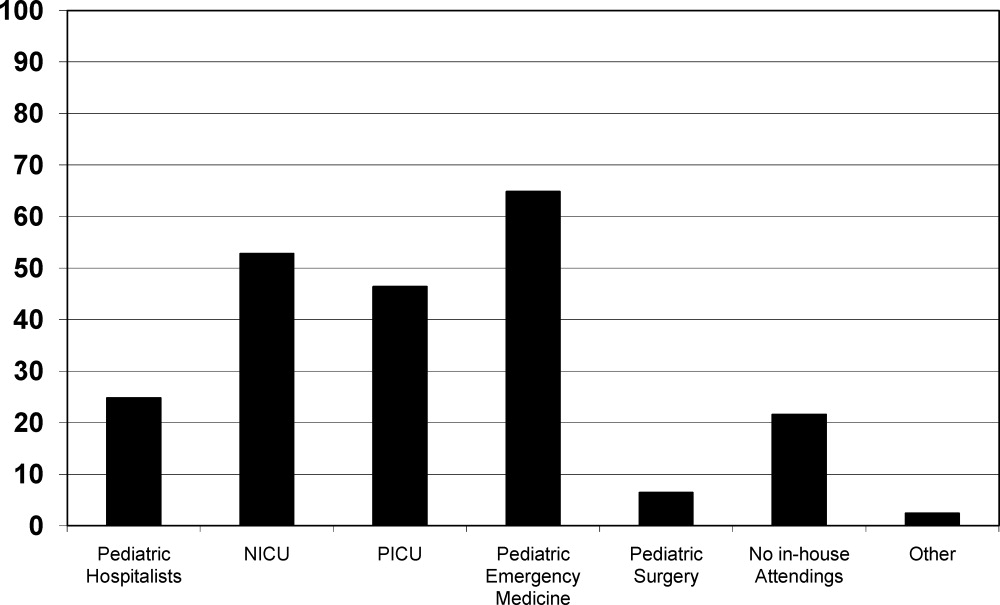

Currently, 30% of responding programs have pediatric hospitalists in‐house at night. This nighttime in‐house coverage includes both partial nighttime coverage (for example, until midnight) and overnight coverage. Forty‐seven percent have neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and 43% have pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in‐house attending coverage. Sixty percent of responding programs have pediatric emergency medicine attendings in‐house at night. Only 12% of programs have no in‐house attending night coverage at all (Figure 3).

Although there was a trend toward increased pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house 24/7, this did not meet statistical significance (16%20%, P=0.36). Programs with night hospitalist coverage were more likely to be small (<30 residents) or large (50+ residents), compared to medium‐sized programs (3049 residents) (P<0.0032). Thirty‐eight percent of small programs, 14% of medium programs, and 41% of large programs have in‐house night hospitalist coverage.

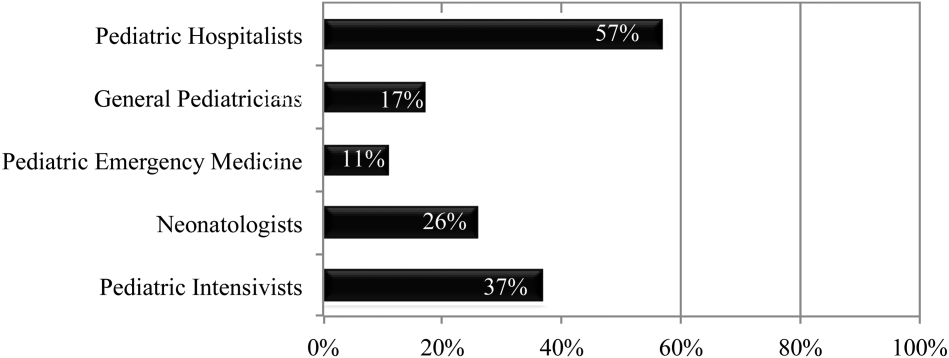

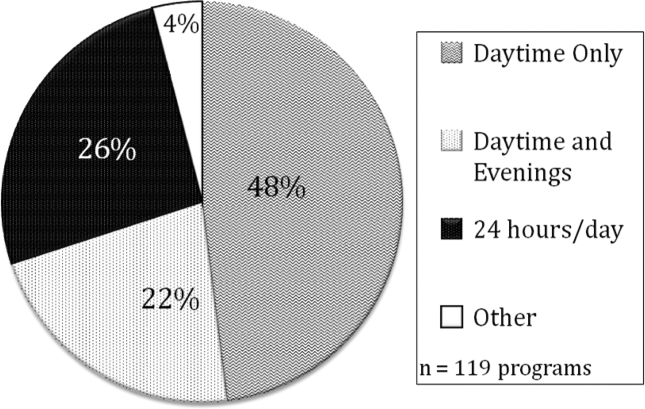

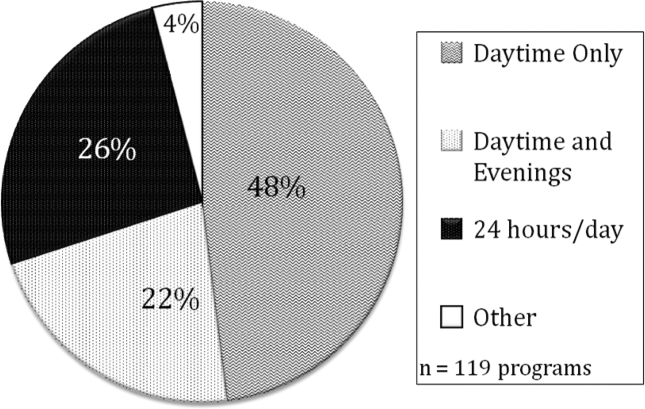

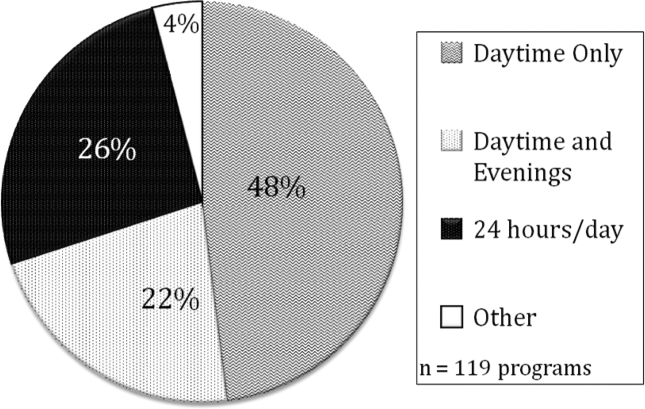

All large programs have some attending physicians in‐house at night (NICU, PICU, pediatric emergency medicine, or hospitalist). All programs with no attendings in‐house at night have fewer than 46 residents. Of programs with pediatric hospitalists (119), hospitalist attendings have in‐house daytime‐only coverage in approximately half the responding programs (48%). The other half of the programs is split between providing some evening coverage (22%) and 24/7 coverage (26%) (Figure 4).

Responsibilities of In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist Attendings at Night

Hospitalist attendings who are in‐house at night have a variety of night responsibilities including approving admission and transfers (65%), teaching residents (74%), consulting for other services (65%), and consulting for residents (65%). They vary in how they staff new patient admissions, with 65% of programs seeing select general pediatric admissions and 35% seeing all general pediatric admissions.

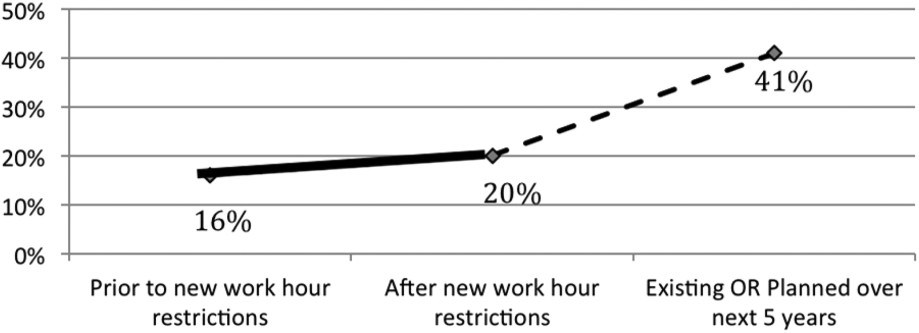

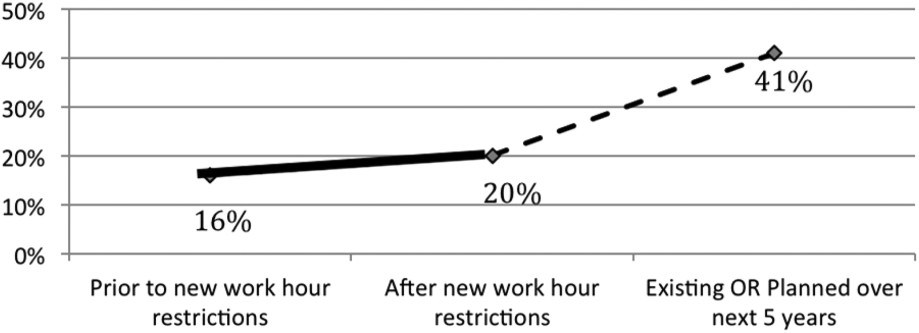

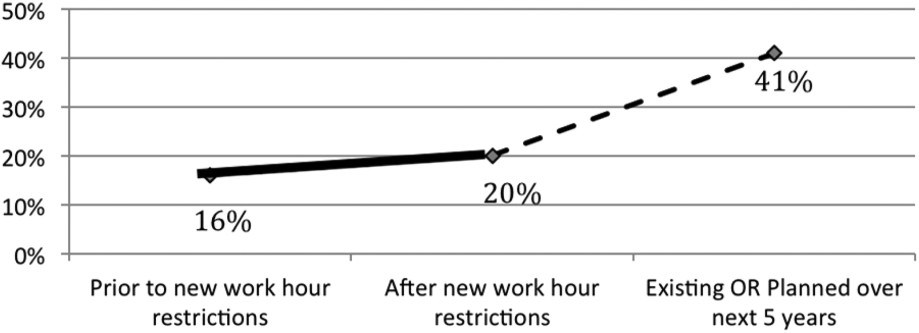

Of the programs without 24/7 pediatric hospital attending coverage, 26% reported that they are planning to add this coverage within the next 5 years. If this occurred, 41% of total responding pediatric residency programs would have 24/7 pediatric hospital coverage (P<0.0001) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Great variation exists in night staffing of pediatric inpatient teaching services. Residency programs have adapted to changes in residency work hours and increased supervision regulations by utilizing night float systems and increasing in‐house attending coverage at night. The largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night since these work‐hour changes has been pediatric hospitalist attendings. Although hospital medicine has been a rapidly growing field over the past 10 years, many program directors in our study felt that the change in resident work hours was the primary driver of increased in‐house attending physicians at night. At the time of this study, pediatric program directors are anticipating an even larger increase in this hospitalist coverage over the next 5 years.

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Patient Safety

The literature is unclear on whether patient safety has improved due to residency work‐hour restrictions. Several studies show decreased mortality among high‐risk patients, but there are conflicting reports on if patient complications have changed.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Two systematic reviews did not show evidence of improved patient safety with increased resident work‐hour restrictions. Some of the studies in these reviews showed a change in medical errors, but no increased patient morbidity and mortality. Although residents were less fatigued with new resident work hours, there is also concern that increased resident handoffs, especially with the increase in resident night float, could lead to medical errors.[16, 17]

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Resident Education

There is concern regarding dissatisfaction among residents, nursing, and training physicians with respect to resident education following the change in residency work‐hour regulations. A systematic review showed negative perceptions of resident education following resident work‐hour restrictions.[18] Another systematic review assessed all intervention studies that reduced resident work shifts over 16 hours, showing no change in resident education with improved patient safety.[19] However, multiple studies done following this systematic review show otherwise.[14, 15, 20, 21] A more recent study showed that although residents were better rested following the shortened work schedule, there was increased work‐load intensity while at work, with decreased patient ownership as well as decreased didactic education (a 25% reduction in ability to attend the noon conference).[20] This could be related to the increase in resident night float seen in our study, resulting in residents not being present during the daytime when much of the didactic education takes place. The number of patient handoffs dramatically increased with an association with higher rates of medical errors.[14, 15, 20, 21] A single‐center study looking specifically at resident education before and after resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented showed improved resident education. This study is hard to generalize due to increased educational programs and redesign of the inpatient services during this time.[22] Although the new resident work‐hour regulations were supposed to increase resident wakefulness, a study on surgical interns found that interns were actually more sleepy on the night float schedule, possibly due to multiple nights of poor sleep without a post‐call day to make it up.[23] Our hypothesis on these conflicting studies is that changes in work‐hour restrictions could result in improved quality of patient care and improved education with the right mix of increased educational programs (on handoffs) and redesign of inpatient services. It is also worth noting that all studies are biased by the constraint of minimal change in resident workload or residency duration. The basic structure of residency may require change to produce the potentially competing goals of improved patient safety and appropriate medical training.

Effects of Increased Resident Supervision and the Role of the In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist at Night

Although increased resident work hours were an important piece of new 2011 ACGME regulations, they also involved increased resident supervision. This may be more important on nights and weekends where there is increased likelihood of patient morbidity and mortality.[24] Our study shows an increase of in‐house attending coverage at night. Although the reasoning for this is likely multifactorial, a large proportion of program directors attributed it to changes in residency work hours. Our study also showed that many of the programs utilized pediatric hospitalist attendings to increase this coverage. A recent study showed that this increased supervision at night improved both the resident education and perception of patient care.[25] Despite this, there is still variation in overnight hospitalist attendings' supervision of trainees, even when hospitalist attendings are present. Our study showed the majority of hospitalist in‐house overnight attendings had roles in teaching and consulting for residents. A different study of internal medicine hospitalist attendings found 61% of these programs had hospitalist attendings in‐house overnight. Only 38% of these programs had formally defined supervisory roles, with almost 25% of the programs with overnight coverage involved in nonteaching services only.[26] although a majority of these hospitalist attending leaders felt formal overnight supervision would improve patient safety and resident education, they were concerned for decreased resident autonomy and increased hospitalist attending workload.[26]

There is little literature specifically on effects of increased resident supervision directly on patient safety since new resident work hours. One large pediatric residency program without 24/7 in‐house attending coverage found that decreasing attending presence by phone did not decrease quality of patient care.[27]

Like all studies, our study has limitations that warrant consideration. Program directors were the respondents in our study. Although they were knowledgeable on residency changes, there may be specific questions on attending responsibilities and future direction of pediatric hospitalist services that may be better answered by specific specialty directors. Although our survey asked for information on the responsibilities of pediatric hospitalist attendings at night, we did not specifically examine responsibilities of nonteaching services. We also did not clarify responsibilities of other attendings (PICU, NICU, emergency medicine) and their utilization of nonteaching services. We did have dropout bias toward the end of our survey. We cannot comment on differences between responding and nonresponding programs, although this is minimized by our large response rate, with similar average program size compared to ACGME data. We are limited by a smaller percentage of small programs responding compared to higher response rates of large and medium‐sized programs. Although program directors predicted large growth of in‐house 24/7 hospitalist coverage, recent economic changes in reimbursement may limit this.[28] Our initial study prior to implementation of 2011 work hours suggested 31% of programs planned to add 24/7 coverage within 5 years.[9] Our current study shows that whereas 24/7 hospitalist coverage is still projected to grow rapidly, it has not yet done so. This could be related to the time to implement 24/7 coverage (hiring staffing for this model and financial concerns) versus the ability of program directors to predict the future of pediatric hospital medicine divisions. Finally, although we feel that the changes in residency work hours likely contributed to the increase in 24/7 hospitalist coverage, this increase is probably multifactorial and could be related to financial and marketing reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study shows that although programs vary in their response to changes in residency work hours, they most commonly utilize night float systems and increased in‐house attending coverage at night, especially among pediatric hospitalist attendings. These changes are likely multifactorial, but many programs attribute increased attending in‐house nighttime coverage to changes in residency work hours. Pediatric hospitalist attendings have had the largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night, with many programs planning to increase in‐house pediatric hospitalist attending coverage at night in the next 5 years. Further investigation is needed to determine the impact of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night on patient outcomes, supervision, and resident education. In the current economic environment with reimbursement rates and national inpatient volumes continuing to decline, hospitals continue to explore options to lower expenses and boost productivity.[28, 29] The perceived need for 24/7 attending in‐house presence may prove to be a financial disincentive for smaller programs and accelerate the shift in pediatric beds to larger, tertiary care settings. A national study may be needed to determine the overall importance and necessity of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night, with regard to maintaining high levels of patient care and residency education while adapting to new economic constraints.

Disclosures: Dr. Oshimura designed the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. She has had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sperring and Dr. Bauer conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Carroll critically reviewed the data collection instruments, analyzed and interpreted the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Rauch conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, reviewed the initial analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. There was no funding source for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–693.

- , , , . The risks and implications of excessive daytime sleepiness in resident physicians. Acad Med. 2002;77:1019–1025.

- , . A brief history of duty hours and resident education. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme‐11‐00‐5‐11%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2014.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Statement of justification/impact for the final approval of common standards related to resident duty hours; September 2002. Available at: www.acgme.org. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , . Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1249–1255.

- Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME, eds. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1829–1837.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME approved standards, effective July 2011. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011%5B2%5D.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , , , . Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(4):299–303.

- , , , . Duty‐hour limits and patient care and resident outcomes: can high‐quality studies offer insight into complex relationships? Ann Rev Med. 2013;64:467–483.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–1848.

- , , , , , . Implementation of resident work hour restrictions is associated with a reduction in mortality and provider‐related complications on the surgical service: a concurrent analysis of 14,610 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):316–321.

- , , , et al. Impact of the 80‐hour workweek on patient care at a level 1 trauma center. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):708–714.

- , , , et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):657–662.

- , . Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work‐hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):73–80.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: effects of resident work hours on patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):851–857.

- , . Restricting resident work hours: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):960–966.

- , , , et al. Sleep deprivation in resident physicians, work hour limitations, and related outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(4):241–249.

- , , . Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , , , , . Better rested, but more stressed? Evidence of the effects of resident work hour restrictions. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):335–343.

- , , . The effect of reducing maximum shift lengths to 16 hours on internal medicine interns' educational opportunities. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):512–518.

- , , , , , . Effects of the new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work hour rules on surgical interns: a prospective study in a community teaching hospital. Am J Surg. 2012;205(2):163–168.

- Nocturnists help avoid night, weekend danger. Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv. 2011;18(11):127.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

- , , , , , . Tempering pediatric hospitalist supervision of residents improves admission process efficiency without decreasing quality of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):106–110.

- . CMS announces Medicare reimbursement changes for 2014. July 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.insidepatientfinance.com/revenue‐cycle‐news/cms‐announces‐medicare‐reimbursement‐changes‐for‐2014. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National estimates on use of hospitals by children from the HCUP Kids Inpatient Database. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed September 12, 2013.

Long work hours with abnormal schedules and extended on‐call periods are common for physicians. Prior to resident work‐hour restrictions, studies showed that sleep‐deprived residents were at increased risk for making errors with decreased decision‐making abilities.[1, 2] Resident work‐hour restrictions and increased attending supervision regulations were initially implemented in 1989 in New York due to concerns for patient safety.[3] In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted this 80‐hour work week standard nationally and restricted residents to a maximum of 30 hours of continuous clinical responsibilities.[4] Due to concern that residents working extending periods of time were at risk for making serious medical errors,[5, 6, 7] the ACGME mandated additional resident work‐hour restrictions in July 2011.8 These changes reduced the maximum hours of continuous clinical responsibilities from 30 to 16 hours for interns, and 28 hours for upper‐level residents, including 4 hours for transition of patient care. Continuous on‐site supervision by attending physicians is not mandated, but programs had to accommodate for the increased emphasis on attending services and supervision of residents, especially at night.[6, 8] Our previous study in 2010, prior to the implementation of new resident work hours, showed 84% of pediatric residency programs had pediatric hospitalists. Of those, 24% had 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage, 22% of pediatric residency programs had no in‐house attendings at night, and 31% of programs at that time planned on adding 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage within the next 5 years if further resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented.[9]

The objective of this study was to determine how inpatient staffing of teaching services within pediatric residency programs has changed following this recent transition of additional resident work hours. We also sought to define current attending physician staffing and explore attending physicians' overnight responsibilities following new ACGME standards, specifically looking at the role of pediatric hospitalists.

METHODS

We developed a Web‐based electronic survey consisting of 23 questions. Many of these questions were multiple choice or numerical values with the option to comment. The survey gathered data on the demographics of pediatric residency programs including: the number of residents in each program, patient admission caps (the total number of patients the resident team can admit overnight), and the use of resident night floats (a resident team working the overnight shift, admitting and cross‐covering patients who will be handed over to a day team in the morning).

We also examined the number of pediatric providers at night, the use of pediatric hospitalists, and specifically the use of attendings in‐house at night and their overnight responsibilities.

The survey was first pilot tested by pediatric hospitalists for face validity. It was reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent to 198 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in May 2012. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or designating someone else to complete it. We sent 2 e‐mail reminders via the listserve with individual e‐mail reminders to nonresponding programs. We sent follow‐up e‐mails and phone calls to programs with current night float systems to clarify their use of resident night float prior to implementation of new work‐hour restrictions. Duplicate responses from a program were removed by initially removing the 1 with incomplete data. If both responses were complete, we removed the second response. We analyzed the use of resident night float systems and admission caps, as well as the use of attending physicians in‐house at night, using a z‐score and [2] test.

The institutional review board of the Indiana University School of Medicine reviewed this study.

RESULTS

Out of 198 pediatric ACGME programs contacted, 152 responses were received, which is a 77% response rate. This represented 7828 pediatric residents, or 79% of total US pediatric residents. Average program size was 52 residents (range, 6168 residents; median, 41). This average program size was similar to the ACGME average program size of 50 residents. Sorting our response rate by program size, all 58 large ACGME programs responded (programs with over 50 residents). Eighty‐four percent (57 programs) of medium‐sized programs responded (programs with 3050 residents). Fifty‐one percent (37 programs) of small programs responded (programs with <30 residents).

Changes in Resident Staffing

Residency programs utilizing night float systems increased from 43% before to 71% after new work hours were implemented (P<0.0001). Overall use of resident admission caps did not significantly change (12%14.5%, P=0.52) (Figure 1).

Changes in Attending Physicians In‐House at Night

Following implementation of new resident work‐hour restrictions, 23% of programs increased the number of attending physicians in‐house at night. Of these programs, 57% (20 programs) increased the number of pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night, whereas 37% increased the number of pediatric intensive care unit attendings (Figure 2). When asked the reason for increased attending physician presence in‐house, 71% of programs attributed this change to increased resident work‐hour restrictions, and 37% attributed it to increased patient census. Other common reasons cited included increased patient acuity as well as improved resident supervision and education.

Currently, 30% of responding programs have pediatric hospitalists in‐house at night. This nighttime in‐house coverage includes both partial nighttime coverage (for example, until midnight) and overnight coverage. Forty‐seven percent have neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and 43% have pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in‐house attending coverage. Sixty percent of responding programs have pediatric emergency medicine attendings in‐house at night. Only 12% of programs have no in‐house attending night coverage at all (Figure 3).

Although there was a trend toward increased pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house 24/7, this did not meet statistical significance (16%20%, P=0.36). Programs with night hospitalist coverage were more likely to be small (<30 residents) or large (50+ residents), compared to medium‐sized programs (3049 residents) (P<0.0032). Thirty‐eight percent of small programs, 14% of medium programs, and 41% of large programs have in‐house night hospitalist coverage.

All large programs have some attending physicians in‐house at night (NICU, PICU, pediatric emergency medicine, or hospitalist). All programs with no attendings in‐house at night have fewer than 46 residents. Of programs with pediatric hospitalists (119), hospitalist attendings have in‐house daytime‐only coverage in approximately half the responding programs (48%). The other half of the programs is split between providing some evening coverage (22%) and 24/7 coverage (26%) (Figure 4).

Responsibilities of In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist Attendings at Night

Hospitalist attendings who are in‐house at night have a variety of night responsibilities including approving admission and transfers (65%), teaching residents (74%), consulting for other services (65%), and consulting for residents (65%). They vary in how they staff new patient admissions, with 65% of programs seeing select general pediatric admissions and 35% seeing all general pediatric admissions.

Of the programs without 24/7 pediatric hospital attending coverage, 26% reported that they are planning to add this coverage within the next 5 years. If this occurred, 41% of total responding pediatric residency programs would have 24/7 pediatric hospital coverage (P<0.0001) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Great variation exists in night staffing of pediatric inpatient teaching services. Residency programs have adapted to changes in residency work hours and increased supervision regulations by utilizing night float systems and increasing in‐house attending coverage at night. The largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night since these work‐hour changes has been pediatric hospitalist attendings. Although hospital medicine has been a rapidly growing field over the past 10 years, many program directors in our study felt that the change in resident work hours was the primary driver of increased in‐house attending physicians at night. At the time of this study, pediatric program directors are anticipating an even larger increase in this hospitalist coverage over the next 5 years.

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Patient Safety

The literature is unclear on whether patient safety has improved due to residency work‐hour restrictions. Several studies show decreased mortality among high‐risk patients, but there are conflicting reports on if patient complications have changed.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Two systematic reviews did not show evidence of improved patient safety with increased resident work‐hour restrictions. Some of the studies in these reviews showed a change in medical errors, but no increased patient morbidity and mortality. Although residents were less fatigued with new resident work hours, there is also concern that increased resident handoffs, especially with the increase in resident night float, could lead to medical errors.[16, 17]

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Resident Education

There is concern regarding dissatisfaction among residents, nursing, and training physicians with respect to resident education following the change in residency work‐hour regulations. A systematic review showed negative perceptions of resident education following resident work‐hour restrictions.[18] Another systematic review assessed all intervention studies that reduced resident work shifts over 16 hours, showing no change in resident education with improved patient safety.[19] However, multiple studies done following this systematic review show otherwise.[14, 15, 20, 21] A more recent study showed that although residents were better rested following the shortened work schedule, there was increased work‐load intensity while at work, with decreased patient ownership as well as decreased didactic education (a 25% reduction in ability to attend the noon conference).[20] This could be related to the increase in resident night float seen in our study, resulting in residents not being present during the daytime when much of the didactic education takes place. The number of patient handoffs dramatically increased with an association with higher rates of medical errors.[14, 15, 20, 21] A single‐center study looking specifically at resident education before and after resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented showed improved resident education. This study is hard to generalize due to increased educational programs and redesign of the inpatient services during this time.[22] Although the new resident work‐hour regulations were supposed to increase resident wakefulness, a study on surgical interns found that interns were actually more sleepy on the night float schedule, possibly due to multiple nights of poor sleep without a post‐call day to make it up.[23] Our hypothesis on these conflicting studies is that changes in work‐hour restrictions could result in improved quality of patient care and improved education with the right mix of increased educational programs (on handoffs) and redesign of inpatient services. It is also worth noting that all studies are biased by the constraint of minimal change in resident workload or residency duration. The basic structure of residency may require change to produce the potentially competing goals of improved patient safety and appropriate medical training.

Effects of Increased Resident Supervision and the Role of the In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist at Night

Although increased resident work hours were an important piece of new 2011 ACGME regulations, they also involved increased resident supervision. This may be more important on nights and weekends where there is increased likelihood of patient morbidity and mortality.[24] Our study shows an increase of in‐house attending coverage at night. Although the reasoning for this is likely multifactorial, a large proportion of program directors attributed it to changes in residency work hours. Our study also showed that many of the programs utilized pediatric hospitalist attendings to increase this coverage. A recent study showed that this increased supervision at night improved both the resident education and perception of patient care.[25] Despite this, there is still variation in overnight hospitalist attendings' supervision of trainees, even when hospitalist attendings are present. Our study showed the majority of hospitalist in‐house overnight attendings had roles in teaching and consulting for residents. A different study of internal medicine hospitalist attendings found 61% of these programs had hospitalist attendings in‐house overnight. Only 38% of these programs had formally defined supervisory roles, with almost 25% of the programs with overnight coverage involved in nonteaching services only.[26] although a majority of these hospitalist attending leaders felt formal overnight supervision would improve patient safety and resident education, they were concerned for decreased resident autonomy and increased hospitalist attending workload.[26]

There is little literature specifically on effects of increased resident supervision directly on patient safety since new resident work hours. One large pediatric residency program without 24/7 in‐house attending coverage found that decreasing attending presence by phone did not decrease quality of patient care.[27]

Like all studies, our study has limitations that warrant consideration. Program directors were the respondents in our study. Although they were knowledgeable on residency changes, there may be specific questions on attending responsibilities and future direction of pediatric hospitalist services that may be better answered by specific specialty directors. Although our survey asked for information on the responsibilities of pediatric hospitalist attendings at night, we did not specifically examine responsibilities of nonteaching services. We also did not clarify responsibilities of other attendings (PICU, NICU, emergency medicine) and their utilization of nonteaching services. We did have dropout bias toward the end of our survey. We cannot comment on differences between responding and nonresponding programs, although this is minimized by our large response rate, with similar average program size compared to ACGME data. We are limited by a smaller percentage of small programs responding compared to higher response rates of large and medium‐sized programs. Although program directors predicted large growth of in‐house 24/7 hospitalist coverage, recent economic changes in reimbursement may limit this.[28] Our initial study prior to implementation of 2011 work hours suggested 31% of programs planned to add 24/7 coverage within 5 years.[9] Our current study shows that whereas 24/7 hospitalist coverage is still projected to grow rapidly, it has not yet done so. This could be related to the time to implement 24/7 coverage (hiring staffing for this model and financial concerns) versus the ability of program directors to predict the future of pediatric hospital medicine divisions. Finally, although we feel that the changes in residency work hours likely contributed to the increase in 24/7 hospitalist coverage, this increase is probably multifactorial and could be related to financial and marketing reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study shows that although programs vary in their response to changes in residency work hours, they most commonly utilize night float systems and increased in‐house attending coverage at night, especially among pediatric hospitalist attendings. These changes are likely multifactorial, but many programs attribute increased attending in‐house nighttime coverage to changes in residency work hours. Pediatric hospitalist attendings have had the largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night, with many programs planning to increase in‐house pediatric hospitalist attending coverage at night in the next 5 years. Further investigation is needed to determine the impact of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night on patient outcomes, supervision, and resident education. In the current economic environment with reimbursement rates and national inpatient volumes continuing to decline, hospitals continue to explore options to lower expenses and boost productivity.[28, 29] The perceived need for 24/7 attending in‐house presence may prove to be a financial disincentive for smaller programs and accelerate the shift in pediatric beds to larger, tertiary care settings. A national study may be needed to determine the overall importance and necessity of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night, with regard to maintaining high levels of patient care and residency education while adapting to new economic constraints.

Disclosures: Dr. Oshimura designed the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. She has had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sperring and Dr. Bauer conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Carroll critically reviewed the data collection instruments, analyzed and interpreted the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Rauch conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, reviewed the initial analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. There was no funding source for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Long work hours with abnormal schedules and extended on‐call periods are common for physicians. Prior to resident work‐hour restrictions, studies showed that sleep‐deprived residents were at increased risk for making errors with decreased decision‐making abilities.[1, 2] Resident work‐hour restrictions and increased attending supervision regulations were initially implemented in 1989 in New York due to concerns for patient safety.[3] In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted this 80‐hour work week standard nationally and restricted residents to a maximum of 30 hours of continuous clinical responsibilities.[4] Due to concern that residents working extending periods of time were at risk for making serious medical errors,[5, 6, 7] the ACGME mandated additional resident work‐hour restrictions in July 2011.8 These changes reduced the maximum hours of continuous clinical responsibilities from 30 to 16 hours for interns, and 28 hours for upper‐level residents, including 4 hours for transition of patient care. Continuous on‐site supervision by attending physicians is not mandated, but programs had to accommodate for the increased emphasis on attending services and supervision of residents, especially at night.[6, 8] Our previous study in 2010, prior to the implementation of new resident work hours, showed 84% of pediatric residency programs had pediatric hospitalists. Of those, 24% had 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage, 22% of pediatric residency programs had no in‐house attendings at night, and 31% of programs at that time planned on adding 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage within the next 5 years if further resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented.[9]

The objective of this study was to determine how inpatient staffing of teaching services within pediatric residency programs has changed following this recent transition of additional resident work hours. We also sought to define current attending physician staffing and explore attending physicians' overnight responsibilities following new ACGME standards, specifically looking at the role of pediatric hospitalists.

METHODS

We developed a Web‐based electronic survey consisting of 23 questions. Many of these questions were multiple choice or numerical values with the option to comment. The survey gathered data on the demographics of pediatric residency programs including: the number of residents in each program, patient admission caps (the total number of patients the resident team can admit overnight), and the use of resident night floats (a resident team working the overnight shift, admitting and cross‐covering patients who will be handed over to a day team in the morning).

We also examined the number of pediatric providers at night, the use of pediatric hospitalists, and specifically the use of attendings in‐house at night and their overnight responsibilities.

The survey was first pilot tested by pediatric hospitalists for face validity. It was reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent to 198 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in May 2012. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or designating someone else to complete it. We sent 2 e‐mail reminders via the listserve with individual e‐mail reminders to nonresponding programs. We sent follow‐up e‐mails and phone calls to programs with current night float systems to clarify their use of resident night float prior to implementation of new work‐hour restrictions. Duplicate responses from a program were removed by initially removing the 1 with incomplete data. If both responses were complete, we removed the second response. We analyzed the use of resident night float systems and admission caps, as well as the use of attending physicians in‐house at night, using a z‐score and [2] test.

The institutional review board of the Indiana University School of Medicine reviewed this study.

RESULTS

Out of 198 pediatric ACGME programs contacted, 152 responses were received, which is a 77% response rate. This represented 7828 pediatric residents, or 79% of total US pediatric residents. Average program size was 52 residents (range, 6168 residents; median, 41). This average program size was similar to the ACGME average program size of 50 residents. Sorting our response rate by program size, all 58 large ACGME programs responded (programs with over 50 residents). Eighty‐four percent (57 programs) of medium‐sized programs responded (programs with 3050 residents). Fifty‐one percent (37 programs) of small programs responded (programs with <30 residents).

Changes in Resident Staffing

Residency programs utilizing night float systems increased from 43% before to 71% after new work hours were implemented (P<0.0001). Overall use of resident admission caps did not significantly change (12%14.5%, P=0.52) (Figure 1).

Changes in Attending Physicians In‐House at Night

Following implementation of new resident work‐hour restrictions, 23% of programs increased the number of attending physicians in‐house at night. Of these programs, 57% (20 programs) increased the number of pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night, whereas 37% increased the number of pediatric intensive care unit attendings (Figure 2). When asked the reason for increased attending physician presence in‐house, 71% of programs attributed this change to increased resident work‐hour restrictions, and 37% attributed it to increased patient census. Other common reasons cited included increased patient acuity as well as improved resident supervision and education.

Currently, 30% of responding programs have pediatric hospitalists in‐house at night. This nighttime in‐house coverage includes both partial nighttime coverage (for example, until midnight) and overnight coverage. Forty‐seven percent have neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and 43% have pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in‐house attending coverage. Sixty percent of responding programs have pediatric emergency medicine attendings in‐house at night. Only 12% of programs have no in‐house attending night coverage at all (Figure 3).

Although there was a trend toward increased pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house 24/7, this did not meet statistical significance (16%20%, P=0.36). Programs with night hospitalist coverage were more likely to be small (<30 residents) or large (50+ residents), compared to medium‐sized programs (3049 residents) (P<0.0032). Thirty‐eight percent of small programs, 14% of medium programs, and 41% of large programs have in‐house night hospitalist coverage.

All large programs have some attending physicians in‐house at night (NICU, PICU, pediatric emergency medicine, or hospitalist). All programs with no attendings in‐house at night have fewer than 46 residents. Of programs with pediatric hospitalists (119), hospitalist attendings have in‐house daytime‐only coverage in approximately half the responding programs (48%). The other half of the programs is split between providing some evening coverage (22%) and 24/7 coverage (26%) (Figure 4).

Responsibilities of In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist Attendings at Night

Hospitalist attendings who are in‐house at night have a variety of night responsibilities including approving admission and transfers (65%), teaching residents (74%), consulting for other services (65%), and consulting for residents (65%). They vary in how they staff new patient admissions, with 65% of programs seeing select general pediatric admissions and 35% seeing all general pediatric admissions.

Of the programs without 24/7 pediatric hospital attending coverage, 26% reported that they are planning to add this coverage within the next 5 years. If this occurred, 41% of total responding pediatric residency programs would have 24/7 pediatric hospital coverage (P<0.0001) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Great variation exists in night staffing of pediatric inpatient teaching services. Residency programs have adapted to changes in residency work hours and increased supervision regulations by utilizing night float systems and increasing in‐house attending coverage at night. The largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night since these work‐hour changes has been pediatric hospitalist attendings. Although hospital medicine has been a rapidly growing field over the past 10 years, many program directors in our study felt that the change in resident work hours was the primary driver of increased in‐house attending physicians at night. At the time of this study, pediatric program directors are anticipating an even larger increase in this hospitalist coverage over the next 5 years.

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Patient Safety

The literature is unclear on whether patient safety has improved due to residency work‐hour restrictions. Several studies show decreased mortality among high‐risk patients, but there are conflicting reports on if patient complications have changed.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Two systematic reviews did not show evidence of improved patient safety with increased resident work‐hour restrictions. Some of the studies in these reviews showed a change in medical errors, but no increased patient morbidity and mortality. Although residents were less fatigued with new resident work hours, there is also concern that increased resident handoffs, especially with the increase in resident night float, could lead to medical errors.[16, 17]

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Resident Education

There is concern regarding dissatisfaction among residents, nursing, and training physicians with respect to resident education following the change in residency work‐hour regulations. A systematic review showed negative perceptions of resident education following resident work‐hour restrictions.[18] Another systematic review assessed all intervention studies that reduced resident work shifts over 16 hours, showing no change in resident education with improved patient safety.[19] However, multiple studies done following this systematic review show otherwise.[14, 15, 20, 21] A more recent study showed that although residents were better rested following the shortened work schedule, there was increased work‐load intensity while at work, with decreased patient ownership as well as decreased didactic education (a 25% reduction in ability to attend the noon conference).[20] This could be related to the increase in resident night float seen in our study, resulting in residents not being present during the daytime when much of the didactic education takes place. The number of patient handoffs dramatically increased with an association with higher rates of medical errors.[14, 15, 20, 21] A single‐center study looking specifically at resident education before and after resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented showed improved resident education. This study is hard to generalize due to increased educational programs and redesign of the inpatient services during this time.[22] Although the new resident work‐hour regulations were supposed to increase resident wakefulness, a study on surgical interns found that interns were actually more sleepy on the night float schedule, possibly due to multiple nights of poor sleep without a post‐call day to make it up.[23] Our hypothesis on these conflicting studies is that changes in work‐hour restrictions could result in improved quality of patient care and improved education with the right mix of increased educational programs (on handoffs) and redesign of inpatient services. It is also worth noting that all studies are biased by the constraint of minimal change in resident workload or residency duration. The basic structure of residency may require change to produce the potentially competing goals of improved patient safety and appropriate medical training.

Effects of Increased Resident Supervision and the Role of the In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist at Night

Although increased resident work hours were an important piece of new 2011 ACGME regulations, they also involved increased resident supervision. This may be more important on nights and weekends where there is increased likelihood of patient morbidity and mortality.[24] Our study shows an increase of in‐house attending coverage at night. Although the reasoning for this is likely multifactorial, a large proportion of program directors attributed it to changes in residency work hours. Our study also showed that many of the programs utilized pediatric hospitalist attendings to increase this coverage. A recent study showed that this increased supervision at night improved both the resident education and perception of patient care.[25] Despite this, there is still variation in overnight hospitalist attendings' supervision of trainees, even when hospitalist attendings are present. Our study showed the majority of hospitalist in‐house overnight attendings had roles in teaching and consulting for residents. A different study of internal medicine hospitalist attendings found 61% of these programs had hospitalist attendings in‐house overnight. Only 38% of these programs had formally defined supervisory roles, with almost 25% of the programs with overnight coverage involved in nonteaching services only.[26] although a majority of these hospitalist attending leaders felt formal overnight supervision would improve patient safety and resident education, they were concerned for decreased resident autonomy and increased hospitalist attending workload.[26]

There is little literature specifically on effects of increased resident supervision directly on patient safety since new resident work hours. One large pediatric residency program without 24/7 in‐house attending coverage found that decreasing attending presence by phone did not decrease quality of patient care.[27]

Like all studies, our study has limitations that warrant consideration. Program directors were the respondents in our study. Although they were knowledgeable on residency changes, there may be specific questions on attending responsibilities and future direction of pediatric hospitalist services that may be better answered by specific specialty directors. Although our survey asked for information on the responsibilities of pediatric hospitalist attendings at night, we did not specifically examine responsibilities of nonteaching services. We also did not clarify responsibilities of other attendings (PICU, NICU, emergency medicine) and their utilization of nonteaching services. We did have dropout bias toward the end of our survey. We cannot comment on differences between responding and nonresponding programs, although this is minimized by our large response rate, with similar average program size compared to ACGME data. We are limited by a smaller percentage of small programs responding compared to higher response rates of large and medium‐sized programs. Although program directors predicted large growth of in‐house 24/7 hospitalist coverage, recent economic changes in reimbursement may limit this.[28] Our initial study prior to implementation of 2011 work hours suggested 31% of programs planned to add 24/7 coverage within 5 years.[9] Our current study shows that whereas 24/7 hospitalist coverage is still projected to grow rapidly, it has not yet done so. This could be related to the time to implement 24/7 coverage (hiring staffing for this model and financial concerns) versus the ability of program directors to predict the future of pediatric hospital medicine divisions. Finally, although we feel that the changes in residency work hours likely contributed to the increase in 24/7 hospitalist coverage, this increase is probably multifactorial and could be related to financial and marketing reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study shows that although programs vary in their response to changes in residency work hours, they most commonly utilize night float systems and increased in‐house attending coverage at night, especially among pediatric hospitalist attendings. These changes are likely multifactorial, but many programs attribute increased attending in‐house nighttime coverage to changes in residency work hours. Pediatric hospitalist attendings have had the largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night, with many programs planning to increase in‐house pediatric hospitalist attending coverage at night in the next 5 years. Further investigation is needed to determine the impact of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night on patient outcomes, supervision, and resident education. In the current economic environment with reimbursement rates and national inpatient volumes continuing to decline, hospitals continue to explore options to lower expenses and boost productivity.[28, 29] The perceived need for 24/7 attending in‐house presence may prove to be a financial disincentive for smaller programs and accelerate the shift in pediatric beds to larger, tertiary care settings. A national study may be needed to determine the overall importance and necessity of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night, with regard to maintaining high levels of patient care and residency education while adapting to new economic constraints.

Disclosures: Dr. Oshimura designed the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. She has had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sperring and Dr. Bauer conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Carroll critically reviewed the data collection instruments, analyzed and interpreted the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Rauch conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, reviewed the initial analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. There was no funding source for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–693.

- , , , . The risks and implications of excessive daytime sleepiness in resident physicians. Acad Med. 2002;77:1019–1025.

- , . A brief history of duty hours and resident education. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme‐11‐00‐5‐11%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2014.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Statement of justification/impact for the final approval of common standards related to resident duty hours; September 2002. Available at: www.acgme.org. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , . Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1249–1255.

- Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME, eds. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1829–1837.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME approved standards, effective July 2011. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011%5B2%5D.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , , , . Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(4):299–303.

- , , , . Duty‐hour limits and patient care and resident outcomes: can high‐quality studies offer insight into complex relationships? Ann Rev Med. 2013;64:467–483.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–1848.

- , , , , , . Implementation of resident work hour restrictions is associated with a reduction in mortality and provider‐related complications on the surgical service: a concurrent analysis of 14,610 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):316–321.

- , , , et al. Impact of the 80‐hour workweek on patient care at a level 1 trauma center. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):708–714.

- , , , et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):657–662.

- , . Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work‐hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):73–80.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: effects of resident work hours on patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):851–857.

- , . Restricting resident work hours: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):960–966.

- , , , et al. Sleep deprivation in resident physicians, work hour limitations, and related outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(4):241–249.

- , , . Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , , , , . Better rested, but more stressed? Evidence of the effects of resident work hour restrictions. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):335–343.

- , , . The effect of reducing maximum shift lengths to 16 hours on internal medicine interns' educational opportunities. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):512–518.

- , , , , , . Effects of the new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work hour rules on surgical interns: a prospective study in a community teaching hospital. Am J Surg. 2012;205(2):163–168.

- Nocturnists help avoid night, weekend danger. Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv. 2011;18(11):127.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

- , , , , , . Tempering pediatric hospitalist supervision of residents improves admission process efficiency without decreasing quality of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):106–110.

- . CMS announces Medicare reimbursement changes for 2014. July 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.insidepatientfinance.com/revenue‐cycle‐news/cms‐announces‐medicare‐reimbursement‐changes‐for‐2014. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National estimates on use of hospitals by children from the HCUP Kids Inpatient Database. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- , . A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–693.

- , , , . The risks and implications of excessive daytime sleepiness in resident physicians. Acad Med. 2002;77:1019–1025.

- , . A brief history of duty hours and resident education. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme‐11‐00‐5‐11%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2014.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Statement of justification/impact for the final approval of common standards related to resident duty hours; September 2002. Available at: www.acgme.org. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , . Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1249–1255.

- Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME, eds. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1829–1837.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME approved standards, effective July 2011. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011%5B2%5D.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , , , . Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(4):299–303.

- , , , . Duty‐hour limits and patient care and resident outcomes: can high‐quality studies offer insight into complex relationships? Ann Rev Med. 2013;64:467–483.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–1848.

- , , , , , . Implementation of resident work hour restrictions is associated with a reduction in mortality and provider‐related complications on the surgical service: a concurrent analysis of 14,610 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):316–321.

- , , , et al. Impact of the 80‐hour workweek on patient care at a level 1 trauma center. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):708–714.

- , , , et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):657–662.

- , . Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work‐hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):73–80.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: effects of resident work hours on patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):851–857.

- , . Restricting resident work hours: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):960–966.

- , , , et al. Sleep deprivation in resident physicians, work hour limitations, and related outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(4):241–249.

- , , . Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , , , , . Better rested, but more stressed? Evidence of the effects of resident work hour restrictions. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):335–343.

- , , . The effect of reducing maximum shift lengths to 16 hours on internal medicine interns' educational opportunities. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):512–518.

- , , , , , . Effects of the new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work hour rules on surgical interns: a prospective study in a community teaching hospital. Am J Surg. 2012;205(2):163–168.

- Nocturnists help avoid night, weekend danger. Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv. 2011;18(11):127.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

- , , , , , . Tempering pediatric hospitalist supervision of residents improves admission process efficiency without decreasing quality of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):106–110.

- . CMS announces Medicare reimbursement changes for 2014. July 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.insidepatientfinance.com/revenue‐cycle‐news/cms‐announces‐medicare‐reimbursement‐changes‐for‐2014. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National estimates on use of hospitals by children from the HCUP Kids Inpatient Database. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed September 12, 2013.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

Inpatient Staffing in Pediatric Programs

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.