User login

Recurrent Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema Refractory to Fresh Frozen Plasma

Angioedema induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) is present in from 0.1% to 0.7% of treated patients and more often involves the head, neck, face, lips, tongue, and larynx.1 ACEI-induced angioedema results from inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), which results in reduced degradation and resultant accumulation of bradykinin, a potent inflammatory mediator.2

The treatment of choice is discontinuing all ACEIs; however, the patient may be at increased risk of a subsequent angioedema attack for many weeks.3 Antihistamines (H1 and H2 receptor blockade), epinephrine, and glucocorticoids are effective in allergic/histaminergic angioedema but are usually ineffective for hereditary angioedema or ACEI angioedema and are not recommended for acute therapy.4 Kallikrein-bradykinin pathway targeted therapies are now approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for hereditary angioedema attacks and have been studied for ACEI-induced angioedema. Ecallantide and icatibant inhibit conversion of precursors to bradykinin. Multiple randomized trials of ecallantide have not shown any advantage over traditional therapies.5 On the other hand, icatibant has shown resolution of angioedema in several case reports and in a randomized trial.6 Icatibant for ACEI-induced angioedema continues to be off-label because the data are conflicting.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man presented with a medical history of arterial hypertension (diagnosed 17 years previously), hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, alcohol dependence, and obesity. His outpatient medications included simvastatin, aripiprazole, losartan/hydrochlorothiazide, and amlodipine. He was voluntarily admitted for inpatient detoxification. After evaluation by the internist, medication reconciliation was done, and the therapy was adjusted according to medication availability. He reported having no drug allergies, and the losartan was changed for lisinopril. About 24 hours after the first dose of lisinopril, the patient developed swelling of the lips. Antihistamine and IV steroids were administered, and the ACEI was discontinued. His baseline vital signs were temperature 98° F, heart rate 83 beats per minute, respiratory rate 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure 150/94, and oxygen saturation 98% by pulse oximeter.

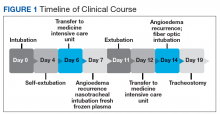

During the night shift the patient’s symptoms worsened, developing difficulty swallowing and shortness of breath. He was transferred to the medicine intensive care unit (MICU), intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation to protect his airway. Laryngoscopic examination was notable for edematous tongue, uvula, and larynx. Also, the patient had mild stridor. His laboratory test results showed normal levels of complement, tryptase, and C1 esterase. On the fourth day after admission to MICU (Figure 1), the patient extubated himself. At that time, he did not present stridor or respiratory distress and remained at the MICU for 24 hours for close monitoring.

Thirty-six hours after self-extubation the patient developed stridor and shortness of breath at the general medicine ward. In view of his clinical presentation of recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema, the Anesthesiology Service was consulted. Direct visualization of the airways showed edema of the epiglottis and vocal cords, requiring nasotracheal intubation. Two units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were administered. Complete resolution of angioedema took at least 72 hours even after the administration of FFP. As part of the ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention bundle, the patient continued with daily spontaneous breathing trials. On the fourth day, he was he was extubated after a cuff-leak test was positive and his rapid shallow breathing index was adequate.

The cuff-leak test is usually done to predict postextubation stridor. It consists of deflating the endotracheal tube cuff to verify if gas can pass around the tube. Absence of cuff leak is suggestive of airway edema, a risk factor for postextubation stridor and failure of extubation. For example, if the patient has an endotracheal tube that is too large in relation to the patient’s airway, the leak test can result in a false negative. In this case, fiber optic visualization of the airway can confirm the endotracheal tube occluding all the airway even with the cuff deflated and without evidence of swelling of the vocal cords. The rapid shallow breathing index is a ratio of respiratory rate over tidal volume in liters and is used to predict successful extubation. Values < 105 have a high sensitivity for successful extubation.

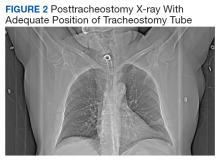

The patient remained under observation for 24 hours in the MICU and then was transferred to the general medicine ward. Unfortunately, 36 hours after, the patient had a new episode of angioedema requiring endotracheal intubation and placement on mechanical ventilation. This was his third episode of angioedema; he had a difficult airway classified as a Cormack-Lehane grade 3, requiring intubation with fiber-optic laryngoscope. In view of the recurrent events, a tracheostomy was done several days later. Figure 2 shows posttracheostomy X-ray with adequate position of the tracheostomy tube.

The patient was transferred to the Respiratory Care Unit and weaned off mechanical ventilation. He completed an intensive physical rehabilitation program and was discharged home. On discharge, he was followed by the Otorhinolaryngology Service and was decannulated about 5 months after. After tracheostomy decannulation, he developed asymptomatic stridor. A neck computer tomography scan revealed soft tissue thickening at the anterior and lateral aspects of the proximal tracheal likely representing granulation tissue/scarring. The findings were consistent with proximal tracheal stenosis sequelae of tracheostomy and intubation. In Figure 3, the upper portion of the curve represents the expiratory limb of the forced vital capacity and the lower portion represents inspiration. The flow-volume loop graph showed flattening of the inspiratory limb. There was a plateau in the inspiratory limb, suggestive of limitation of inspiratory flow as seen in variable extrathoracic lesions, such as glotticstricture, tumors, and vocal cord paralysis.7 The findings on the flow-volume loop were consistent with the subglottic stenosis identified by laryngoscopic examination. The patient was reluctant to undergo further interventions.

Discussion

The standard therapy for ACEI-inducedangioedema continues to be airway management and discontinuation of medication. However, life-threatening progression of symptoms have led to the use of off-label therapies, including FFP and bradykinin receptor antagonists, such as icatibant, which has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Icatibant is expensive and most hospitals do not have access to it. When considering the bradykinin pathway for therapy, FFP is commonly used. The cases described in the literature that have reported success with the use of FFP have used up to 2 units. There is no reported benefit of its use beyond 2 units. The initial randomized trials of icatibant for ACEI angioedema showed decreased time of resolution of angioedema.6 However, repeated trials showed conflicting results. At Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System, this medication was not available, and we decided to use FFP to improve the patient’s symptoms.

The administration of 2 units of FFP has been documented on case reports as a method to decrease the time of resolution of angioedema and the risk of recurrence. The mechanism of action thought to be involved includes the degradation of bradykinin by the enzyme ACE into inactive peptides and by supplying C1 inhibitor.8 No randomized clinical trial has investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of ACEI-induced angioedema. However, a retrospective cohort study report compared patients who presented with acute (nonhereditary) angioedema and airway compromise and received FFP with patients who were not treated with FFP.9 The study suggested a shorter ICU stay in the group treated with FFP, but the findings did not present statistical outcomes.

Nevertheless, our patient had recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema refractory to FFP. In addition to ACE or kininase II, FFP contains high-molecular weight-kininogen and kallikrein, the substrates that form bradykinin, which explained the mechanism of worsening angioedema.10 No randomized trials have investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of bradykinin-induced angioedema nor the appropriate dose.

Conclusion

In view of the emerging case reports of the effectiveness of FFP, this case of refractory angioedema raises concern for its true effectiveness and other possible factors involved in the mechanism of recurrence. Probably it would be unwise to conduct randomized studies in clinical situations such as the ones outlined. A collection of case series where FFP administration was done may be a more reasonable source of conclusions to be analyzed by a panel of experts.

1. Sánchez-Borges M, González-Aveledo LA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(3):195-198.

2. Kaplan AP. Angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1(6):103-113.

3. Moellman JJ, Bernstein JA, Lindsell C, et al; American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM). A consensus parameter for the evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):469-484.

4. LoVerde D, Files DC, Krishnaswamy G. Angioedema. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):725-735.

5. van den Elzen M, Go MFLC, Knulst AC, Blankestijn MA, van Os-Medendorp H, Otten HG. Efficacy of treatment of non-hereditary angioedema. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;54(3):412-431.

6. Bas M, Greve J, Stelter S, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ace-inhibitor–induced angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):418-425.

7. Diaz J, Casal J, Rodriguez W. Flow-volume loops: clinical correlation. PR Health Sci J. 2008;27(2):181-182.

8. Stewart M, McGlone R. Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii:bcr2012006849.

9. Saeb A, Hagglund KH, Cigolle CT. Using fresh frozen plasma for acute airway angioedema to prevent intubation in the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med Int. 2016;2016:6091510.

10. Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(12):1377-1382.

Angioedema induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) is present in from 0.1% to 0.7% of treated patients and more often involves the head, neck, face, lips, tongue, and larynx.1 ACEI-induced angioedema results from inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), which results in reduced degradation and resultant accumulation of bradykinin, a potent inflammatory mediator.2

The treatment of choice is discontinuing all ACEIs; however, the patient may be at increased risk of a subsequent angioedema attack for many weeks.3 Antihistamines (H1 and H2 receptor blockade), epinephrine, and glucocorticoids are effective in allergic/histaminergic angioedema but are usually ineffective for hereditary angioedema or ACEI angioedema and are not recommended for acute therapy.4 Kallikrein-bradykinin pathway targeted therapies are now approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for hereditary angioedema attacks and have been studied for ACEI-induced angioedema. Ecallantide and icatibant inhibit conversion of precursors to bradykinin. Multiple randomized trials of ecallantide have not shown any advantage over traditional therapies.5 On the other hand, icatibant has shown resolution of angioedema in several case reports and in a randomized trial.6 Icatibant for ACEI-induced angioedema continues to be off-label because the data are conflicting.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man presented with a medical history of arterial hypertension (diagnosed 17 years previously), hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, alcohol dependence, and obesity. His outpatient medications included simvastatin, aripiprazole, losartan/hydrochlorothiazide, and amlodipine. He was voluntarily admitted for inpatient detoxification. After evaluation by the internist, medication reconciliation was done, and the therapy was adjusted according to medication availability. He reported having no drug allergies, and the losartan was changed for lisinopril. About 24 hours after the first dose of lisinopril, the patient developed swelling of the lips. Antihistamine and IV steroids were administered, and the ACEI was discontinued. His baseline vital signs were temperature 98° F, heart rate 83 beats per minute, respiratory rate 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure 150/94, and oxygen saturation 98% by pulse oximeter.

During the night shift the patient’s symptoms worsened, developing difficulty swallowing and shortness of breath. He was transferred to the medicine intensive care unit (MICU), intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation to protect his airway. Laryngoscopic examination was notable for edematous tongue, uvula, and larynx. Also, the patient had mild stridor. His laboratory test results showed normal levels of complement, tryptase, and C1 esterase. On the fourth day after admission to MICU (Figure 1), the patient extubated himself. At that time, he did not present stridor or respiratory distress and remained at the MICU for 24 hours for close monitoring.

Thirty-six hours after self-extubation the patient developed stridor and shortness of breath at the general medicine ward. In view of his clinical presentation of recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema, the Anesthesiology Service was consulted. Direct visualization of the airways showed edema of the epiglottis and vocal cords, requiring nasotracheal intubation. Two units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were administered. Complete resolution of angioedema took at least 72 hours even after the administration of FFP. As part of the ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention bundle, the patient continued with daily spontaneous breathing trials. On the fourth day, he was he was extubated after a cuff-leak test was positive and his rapid shallow breathing index was adequate.

The cuff-leak test is usually done to predict postextubation stridor. It consists of deflating the endotracheal tube cuff to verify if gas can pass around the tube. Absence of cuff leak is suggestive of airway edema, a risk factor for postextubation stridor and failure of extubation. For example, if the patient has an endotracheal tube that is too large in relation to the patient’s airway, the leak test can result in a false negative. In this case, fiber optic visualization of the airway can confirm the endotracheal tube occluding all the airway even with the cuff deflated and without evidence of swelling of the vocal cords. The rapid shallow breathing index is a ratio of respiratory rate over tidal volume in liters and is used to predict successful extubation. Values < 105 have a high sensitivity for successful extubation.

The patient remained under observation for 24 hours in the MICU and then was transferred to the general medicine ward. Unfortunately, 36 hours after, the patient had a new episode of angioedema requiring endotracheal intubation and placement on mechanical ventilation. This was his third episode of angioedema; he had a difficult airway classified as a Cormack-Lehane grade 3, requiring intubation with fiber-optic laryngoscope. In view of the recurrent events, a tracheostomy was done several days later. Figure 2 shows posttracheostomy X-ray with adequate position of the tracheostomy tube.

The patient was transferred to the Respiratory Care Unit and weaned off mechanical ventilation. He completed an intensive physical rehabilitation program and was discharged home. On discharge, he was followed by the Otorhinolaryngology Service and was decannulated about 5 months after. After tracheostomy decannulation, he developed asymptomatic stridor. A neck computer tomography scan revealed soft tissue thickening at the anterior and lateral aspects of the proximal tracheal likely representing granulation tissue/scarring. The findings were consistent with proximal tracheal stenosis sequelae of tracheostomy and intubation. In Figure 3, the upper portion of the curve represents the expiratory limb of the forced vital capacity and the lower portion represents inspiration. The flow-volume loop graph showed flattening of the inspiratory limb. There was a plateau in the inspiratory limb, suggestive of limitation of inspiratory flow as seen in variable extrathoracic lesions, such as glotticstricture, tumors, and vocal cord paralysis.7 The findings on the flow-volume loop were consistent with the subglottic stenosis identified by laryngoscopic examination. The patient was reluctant to undergo further interventions.

Discussion

The standard therapy for ACEI-inducedangioedema continues to be airway management and discontinuation of medication. However, life-threatening progression of symptoms have led to the use of off-label therapies, including FFP and bradykinin receptor antagonists, such as icatibant, which has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Icatibant is expensive and most hospitals do not have access to it. When considering the bradykinin pathway for therapy, FFP is commonly used. The cases described in the literature that have reported success with the use of FFP have used up to 2 units. There is no reported benefit of its use beyond 2 units. The initial randomized trials of icatibant for ACEI angioedema showed decreased time of resolution of angioedema.6 However, repeated trials showed conflicting results. At Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System, this medication was not available, and we decided to use FFP to improve the patient’s symptoms.

The administration of 2 units of FFP has been documented on case reports as a method to decrease the time of resolution of angioedema and the risk of recurrence. The mechanism of action thought to be involved includes the degradation of bradykinin by the enzyme ACE into inactive peptides and by supplying C1 inhibitor.8 No randomized clinical trial has investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of ACEI-induced angioedema. However, a retrospective cohort study report compared patients who presented with acute (nonhereditary) angioedema and airway compromise and received FFP with patients who were not treated with FFP.9 The study suggested a shorter ICU stay in the group treated with FFP, but the findings did not present statistical outcomes.

Nevertheless, our patient had recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema refractory to FFP. In addition to ACE or kininase II, FFP contains high-molecular weight-kininogen and kallikrein, the substrates that form bradykinin, which explained the mechanism of worsening angioedema.10 No randomized trials have investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of bradykinin-induced angioedema nor the appropriate dose.

Conclusion

In view of the emerging case reports of the effectiveness of FFP, this case of refractory angioedema raises concern for its true effectiveness and other possible factors involved in the mechanism of recurrence. Probably it would be unwise to conduct randomized studies in clinical situations such as the ones outlined. A collection of case series where FFP administration was done may be a more reasonable source of conclusions to be analyzed by a panel of experts.

Angioedema induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) is present in from 0.1% to 0.7% of treated patients and more often involves the head, neck, face, lips, tongue, and larynx.1 ACEI-induced angioedema results from inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), which results in reduced degradation and resultant accumulation of bradykinin, a potent inflammatory mediator.2

The treatment of choice is discontinuing all ACEIs; however, the patient may be at increased risk of a subsequent angioedema attack for many weeks.3 Antihistamines (H1 and H2 receptor blockade), epinephrine, and glucocorticoids are effective in allergic/histaminergic angioedema but are usually ineffective for hereditary angioedema or ACEI angioedema and are not recommended for acute therapy.4 Kallikrein-bradykinin pathway targeted therapies are now approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for hereditary angioedema attacks and have been studied for ACEI-induced angioedema. Ecallantide and icatibant inhibit conversion of precursors to bradykinin. Multiple randomized trials of ecallantide have not shown any advantage over traditional therapies.5 On the other hand, icatibant has shown resolution of angioedema in several case reports and in a randomized trial.6 Icatibant for ACEI-induced angioedema continues to be off-label because the data are conflicting.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man presented with a medical history of arterial hypertension (diagnosed 17 years previously), hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, alcohol dependence, and obesity. His outpatient medications included simvastatin, aripiprazole, losartan/hydrochlorothiazide, and amlodipine. He was voluntarily admitted for inpatient detoxification. After evaluation by the internist, medication reconciliation was done, and the therapy was adjusted according to medication availability. He reported having no drug allergies, and the losartan was changed for lisinopril. About 24 hours after the first dose of lisinopril, the patient developed swelling of the lips. Antihistamine and IV steroids were administered, and the ACEI was discontinued. His baseline vital signs were temperature 98° F, heart rate 83 beats per minute, respiratory rate 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure 150/94, and oxygen saturation 98% by pulse oximeter.

During the night shift the patient’s symptoms worsened, developing difficulty swallowing and shortness of breath. He was transferred to the medicine intensive care unit (MICU), intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation to protect his airway. Laryngoscopic examination was notable for edematous tongue, uvula, and larynx. Also, the patient had mild stridor. His laboratory test results showed normal levels of complement, tryptase, and C1 esterase. On the fourth day after admission to MICU (Figure 1), the patient extubated himself. At that time, he did not present stridor or respiratory distress and remained at the MICU for 24 hours for close monitoring.

Thirty-six hours after self-extubation the patient developed stridor and shortness of breath at the general medicine ward. In view of his clinical presentation of recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema, the Anesthesiology Service was consulted. Direct visualization of the airways showed edema of the epiglottis and vocal cords, requiring nasotracheal intubation. Two units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were administered. Complete resolution of angioedema took at least 72 hours even after the administration of FFP. As part of the ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention bundle, the patient continued with daily spontaneous breathing trials. On the fourth day, he was he was extubated after a cuff-leak test was positive and his rapid shallow breathing index was adequate.

The cuff-leak test is usually done to predict postextubation stridor. It consists of deflating the endotracheal tube cuff to verify if gas can pass around the tube. Absence of cuff leak is suggestive of airway edema, a risk factor for postextubation stridor and failure of extubation. For example, if the patient has an endotracheal tube that is too large in relation to the patient’s airway, the leak test can result in a false negative. In this case, fiber optic visualization of the airway can confirm the endotracheal tube occluding all the airway even with the cuff deflated and without evidence of swelling of the vocal cords. The rapid shallow breathing index is a ratio of respiratory rate over tidal volume in liters and is used to predict successful extubation. Values < 105 have a high sensitivity for successful extubation.

The patient remained under observation for 24 hours in the MICU and then was transferred to the general medicine ward. Unfortunately, 36 hours after, the patient had a new episode of angioedema requiring endotracheal intubation and placement on mechanical ventilation. This was his third episode of angioedema; he had a difficult airway classified as a Cormack-Lehane grade 3, requiring intubation with fiber-optic laryngoscope. In view of the recurrent events, a tracheostomy was done several days later. Figure 2 shows posttracheostomy X-ray with adequate position of the tracheostomy tube.

The patient was transferred to the Respiratory Care Unit and weaned off mechanical ventilation. He completed an intensive physical rehabilitation program and was discharged home. On discharge, he was followed by the Otorhinolaryngology Service and was decannulated about 5 months after. After tracheostomy decannulation, he developed asymptomatic stridor. A neck computer tomography scan revealed soft tissue thickening at the anterior and lateral aspects of the proximal tracheal likely representing granulation tissue/scarring. The findings were consistent with proximal tracheal stenosis sequelae of tracheostomy and intubation. In Figure 3, the upper portion of the curve represents the expiratory limb of the forced vital capacity and the lower portion represents inspiration. The flow-volume loop graph showed flattening of the inspiratory limb. There was a plateau in the inspiratory limb, suggestive of limitation of inspiratory flow as seen in variable extrathoracic lesions, such as glotticstricture, tumors, and vocal cord paralysis.7 The findings on the flow-volume loop were consistent with the subglottic stenosis identified by laryngoscopic examination. The patient was reluctant to undergo further interventions.

Discussion

The standard therapy for ACEI-inducedangioedema continues to be airway management and discontinuation of medication. However, life-threatening progression of symptoms have led to the use of off-label therapies, including FFP and bradykinin receptor antagonists, such as icatibant, which has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Icatibant is expensive and most hospitals do not have access to it. When considering the bradykinin pathway for therapy, FFP is commonly used. The cases described in the literature that have reported success with the use of FFP have used up to 2 units. There is no reported benefit of its use beyond 2 units. The initial randomized trials of icatibant for ACEI angioedema showed decreased time of resolution of angioedema.6 However, repeated trials showed conflicting results. At Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System, this medication was not available, and we decided to use FFP to improve the patient’s symptoms.

The administration of 2 units of FFP has been documented on case reports as a method to decrease the time of resolution of angioedema and the risk of recurrence. The mechanism of action thought to be involved includes the degradation of bradykinin by the enzyme ACE into inactive peptides and by supplying C1 inhibitor.8 No randomized clinical trial has investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of ACEI-induced angioedema. However, a retrospective cohort study report compared patients who presented with acute (nonhereditary) angioedema and airway compromise and received FFP with patients who were not treated with FFP.9 The study suggested a shorter ICU stay in the group treated with FFP, but the findings did not present statistical outcomes.

Nevertheless, our patient had recurrent ACEI-induced angioedema refractory to FFP. In addition to ACE or kininase II, FFP contains high-molecular weight-kininogen and kallikrein, the substrates that form bradykinin, which explained the mechanism of worsening angioedema.10 No randomized trials have investigated the use of FFP for the treatment of bradykinin-induced angioedema nor the appropriate dose.

Conclusion

In view of the emerging case reports of the effectiveness of FFP, this case of refractory angioedema raises concern for its true effectiveness and other possible factors involved in the mechanism of recurrence. Probably it would be unwise to conduct randomized studies in clinical situations such as the ones outlined. A collection of case series where FFP administration was done may be a more reasonable source of conclusions to be analyzed by a panel of experts.

1. Sánchez-Borges M, González-Aveledo LA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(3):195-198.

2. Kaplan AP. Angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1(6):103-113.

3. Moellman JJ, Bernstein JA, Lindsell C, et al; American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM). A consensus parameter for the evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):469-484.

4. LoVerde D, Files DC, Krishnaswamy G. Angioedema. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):725-735.

5. van den Elzen M, Go MFLC, Knulst AC, Blankestijn MA, van Os-Medendorp H, Otten HG. Efficacy of treatment of non-hereditary angioedema. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;54(3):412-431.

6. Bas M, Greve J, Stelter S, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ace-inhibitor–induced angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):418-425.

7. Diaz J, Casal J, Rodriguez W. Flow-volume loops: clinical correlation. PR Health Sci J. 2008;27(2):181-182.

8. Stewart M, McGlone R. Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii:bcr2012006849.

9. Saeb A, Hagglund KH, Cigolle CT. Using fresh frozen plasma for acute airway angioedema to prevent intubation in the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med Int. 2016;2016:6091510.

10. Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(12):1377-1382.

1. Sánchez-Borges M, González-Aveledo LA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(3):195-198.

2. Kaplan AP. Angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1(6):103-113.

3. Moellman JJ, Bernstein JA, Lindsell C, et al; American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM). A consensus parameter for the evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):469-484.

4. LoVerde D, Files DC, Krishnaswamy G. Angioedema. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):725-735.

5. van den Elzen M, Go MFLC, Knulst AC, Blankestijn MA, van Os-Medendorp H, Otten HG. Efficacy of treatment of non-hereditary angioedema. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;54(3):412-431.

6. Bas M, Greve J, Stelter S, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ace-inhibitor–induced angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):418-425.

7. Diaz J, Casal J, Rodriguez W. Flow-volume loops: clinical correlation. PR Health Sci J. 2008;27(2):181-182.

8. Stewart M, McGlone R. Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii:bcr2012006849.

9. Saeb A, Hagglund KH, Cigolle CT. Using fresh frozen plasma for acute airway angioedema to prevent intubation in the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med Int. 2016;2016:6091510.

10. Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(12):1377-1382.