User login

Erythema Ab Igne: A Clinical Review

Erythema ab igne (EAI)(also known as toasted skin syndrome) was first described in the British Journal of Dermatology in the 20th century, 1 though it was known by physicians long before. Reticular netlike skin changes were seen in association with patients who spent extended time directly next to a heat source. This association led to the name of this condition, which literally means “redness by fire.” Indeed, EAI induced by chronic heat exposure has been described across the world for centuries. For example, in the cold regions of northern China, people used to sleep on beds of hot bricks called kang to stay warm at night. The people of India’s Kashmir district carried pots of hot coals called kangri next to the skin under large woven shawls to stay warm. In the past, Irish women often spent much time by a turf- or peat-burning fire. Chronic heat exposure in these cases can lead not only to EAI but also to aggressive types of cancer, often with a latency of 30 years or more. 2

More recently, the invention of home central heating led to a stark decrease in the number of cases associated with combustion-based heat, with a transition to etiologies such as use of hot water bottles, electric blankets, and electric space heaters. Over time, technological advances led to ever-increasing potential causes for EAI, such as laptops or cell phones, car heaters and heated seats, heated blankets,3,4 infrared lamps for food, and even medical devices such as ultrasound-based heating products and convective temperature management systems for hospitalized patients. As technology evolves, so do the potential causes of EAI, requiring clinicians to diagnose and deduce the cause through a thorough social and medical history as well as a workup on the present illness with considerations for the anatomical location.5-7 Herein, we describe the etiology of EAI, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Clinical Characteristics

Erythema ab igne begins as mild, transient, and erythematous macules and patches in a reticular pattern that resolve minutes to hours after removal of the heat source. With weeks to months of continued or repeated application of the heat source, the affected area eventually becomes hyperpigmented where there once was erythema (Figures 1 and 2). Sometimes papules, bullae, telangiectasia, and hyperkeratosis also form. The rash usually is asymptomatic, though pain, pruritus, and dysesthesia have been reported.7 Dermoscopy of EAI in the hyperpigmented stage can reveal diffuse superficial dark pigmentation, telangiectasia, and mild whitish scaling.8 Although the pathogenesis has remained elusive over the years, lesions do seem to be mostly associated with cumulative exposure to heat rather than length of exposure.7

Etiology of EAI

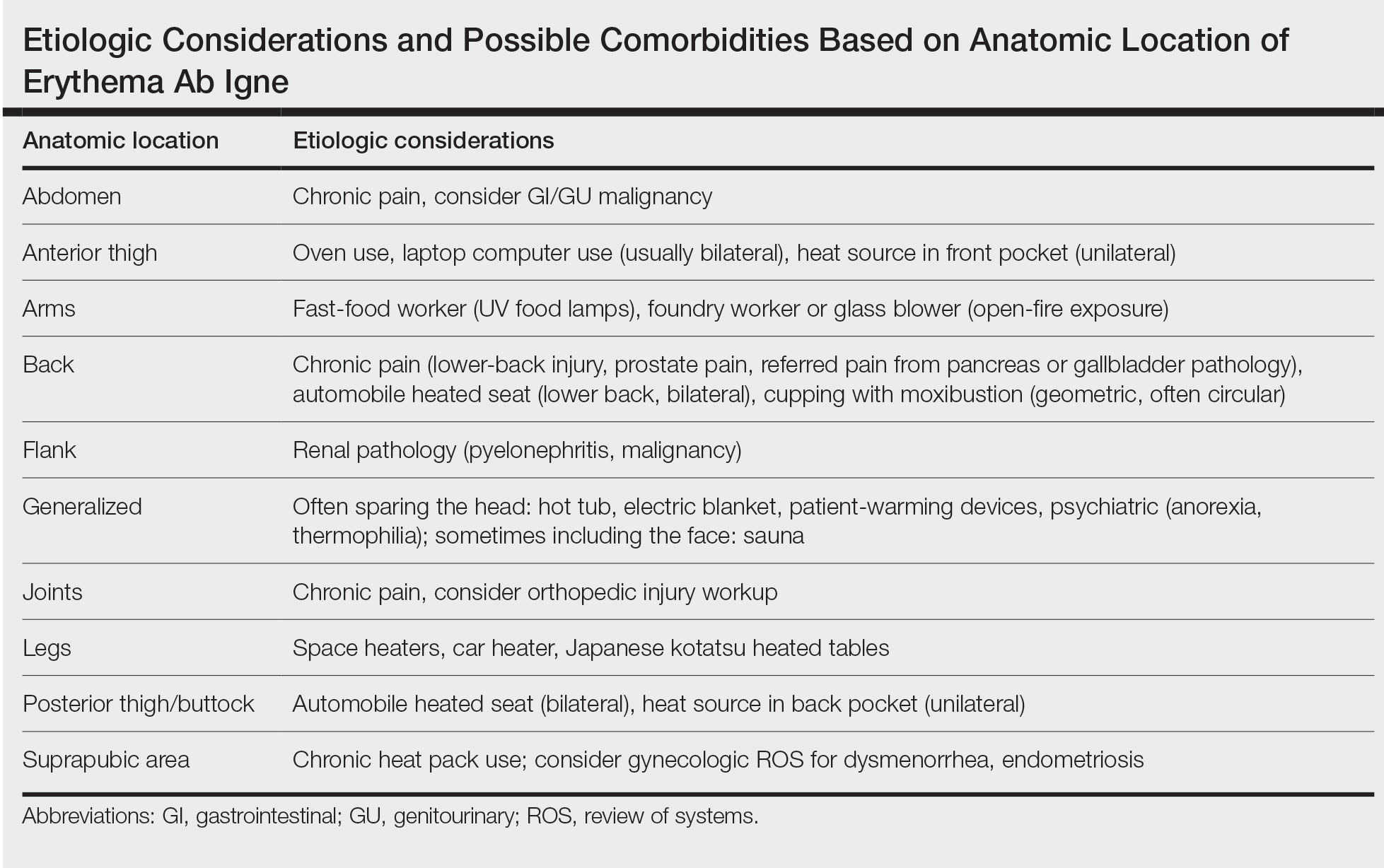

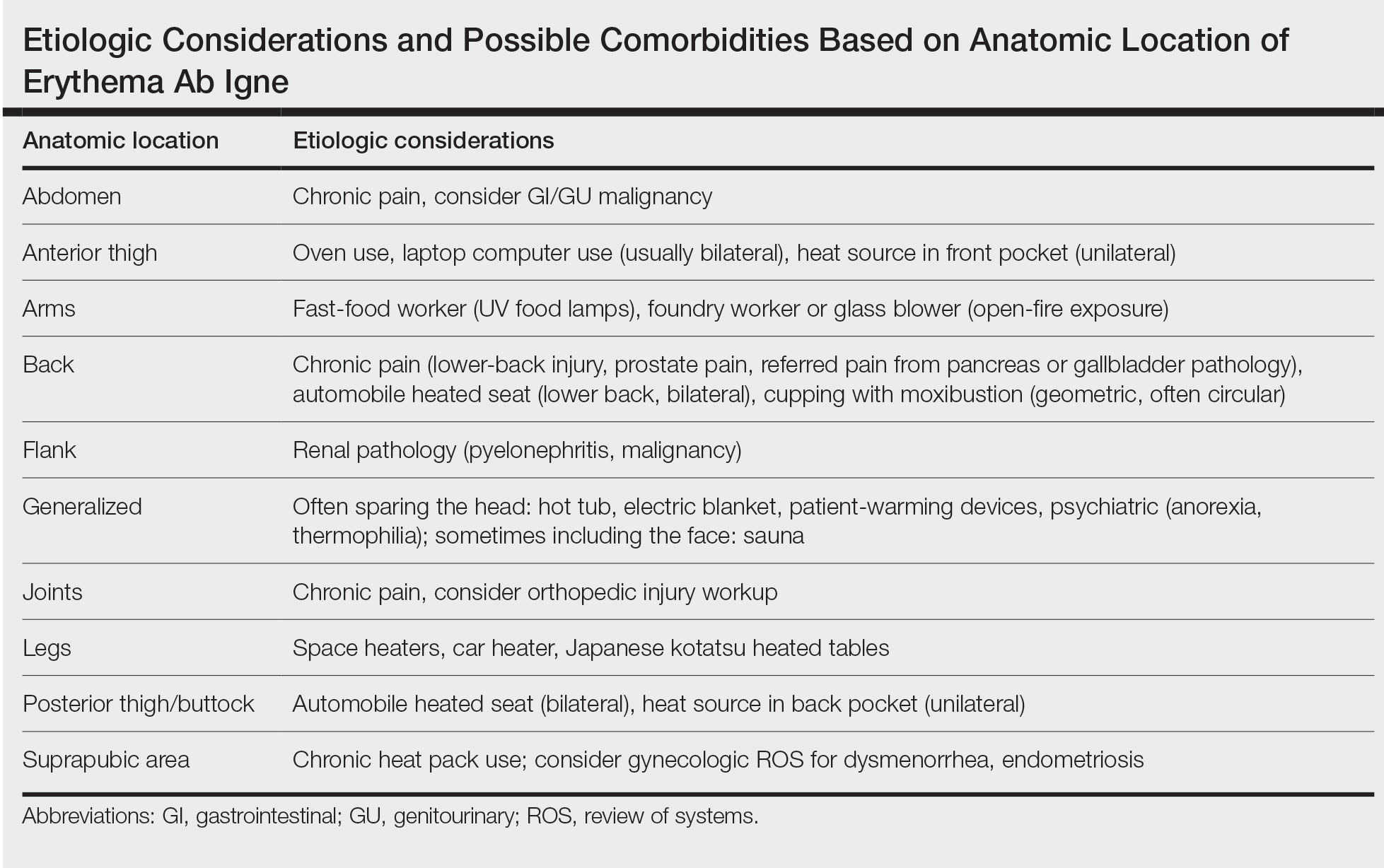

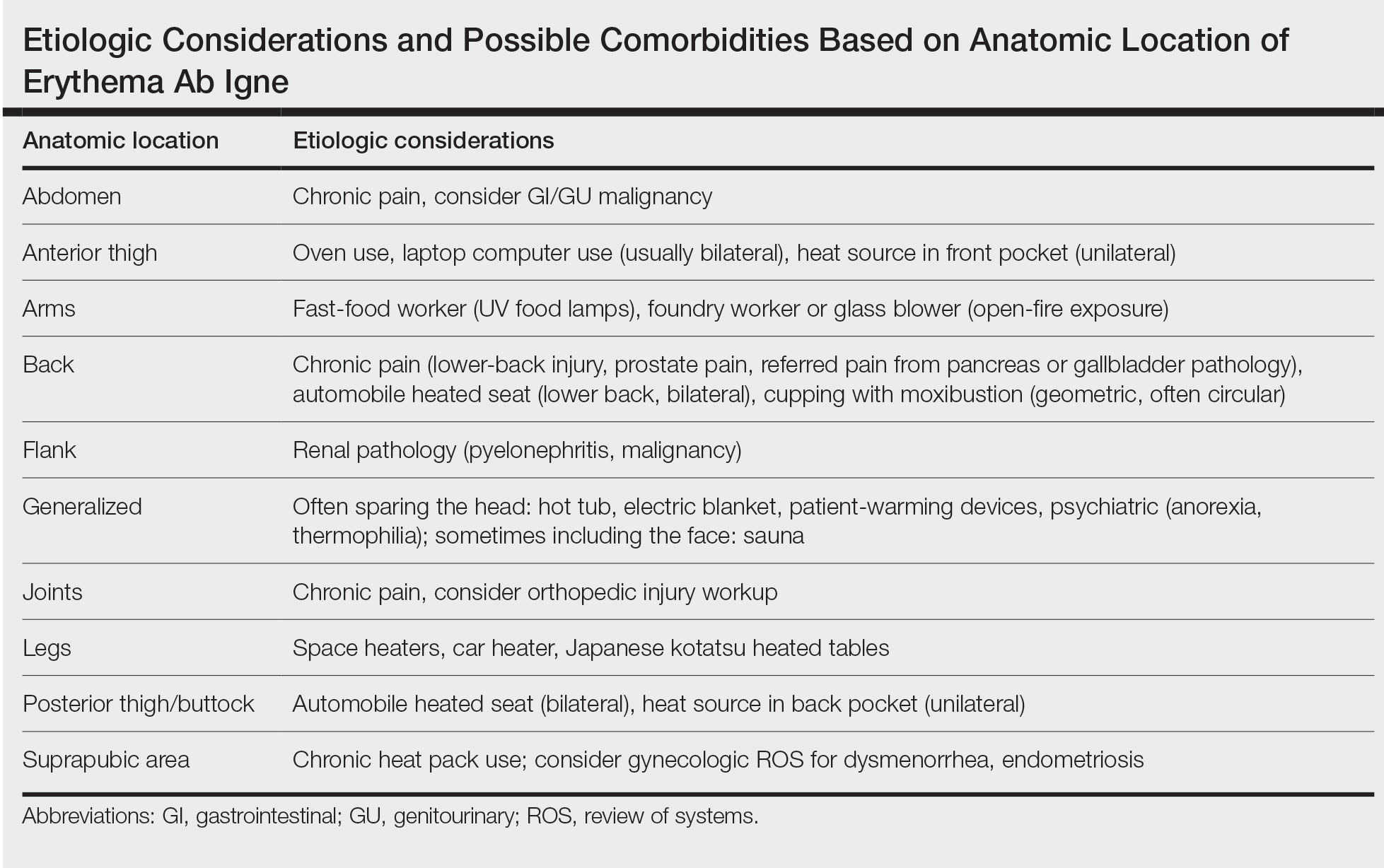

Anatomic Location—The affected site depends on the source of heat (Table). Classic examples of this condition include a patient with EAI presenting on the anterior thighs after working in front of a hot oven or a patient with chronic back pain presenting with lower-back EAI secondary to frequent use of a hot water bottle or heating pad.7 With evolving technology over the last few decades, new etiologies have become more common—teenagers are presenting with anterior thigh EAI secondary to frequent laptop use2-29; patients are holding warm cell phones in their pant pockets, leading to unilateral geometric EAI on the anterior thigh (front pocket) or buttock (back pocket)30; plug-in radiators under computer desks are causing EAI on the lower legs31-34; and automobile seat heaters have been shown to cause EAI on the posterior legs.5,35-37 Clinicians should consider anatomic location a critical clue for etiology.

Social History—There are rarer and more highly specific causes of EAI than simple heat exposure that can be parsed from a patient’s social history. Occupational exposure has been documented, such as bakers with exposure to ovens, foundry workers with exposure to heated metals, or fast-food workers with chronic exposure to infrared food lamps.6,7 There also are cultural practices that can cause EAI. For example, the practice of cupping with moxibustion was shown to create a specific pattern in the shape of the cultural tool used.38 When footbaths with Chinese herbal remedies are performed frequently with high heat, they can lead to EAI on the feet with a linear border at the ankles. There also have been reports of kotatsu (heated tables in Japan) leading to lower-body EAI.39,40 These cultural practices also are more common in patients with darker skin types, which can lead to hyperpigmentation that is difficult to treat, making early diagnosis important.7

Medical History—Case reports have shown EAI caused by patients attempting to use heat-based methods for pain relief of an underlying serious disease such as cancer, bowel pathology (abdominal EAI), spinal disc prolapse (midline back EAI),41 sickle cell anemia, and renal pathology (posterior upper flank EAI).6,7,40-49 Patients with hypothyroidism or anorexia have been noted to have generalized EAI sparing the face secondary to repeated and extended hot baths or showers.50-53 One patient with schizophrenia was shown to have associated thermophilia due to a delusion that led the patient to soak in hot baths for long periods of time, leading to EAI.54 Finally, all physicians should be aware of iatrogenic causes of EAI, such as use of warming devices, ultrasound-based warming techniques, and laser therapy for lipolysis. Inquire about the patient’s surgical history or intensive care unit stays as well as alternative medicine or chiropractic visits. Obtaining a history of medical procedures can be enlightening when an etiology is not immediately clear.7,55,56

Diagnosis

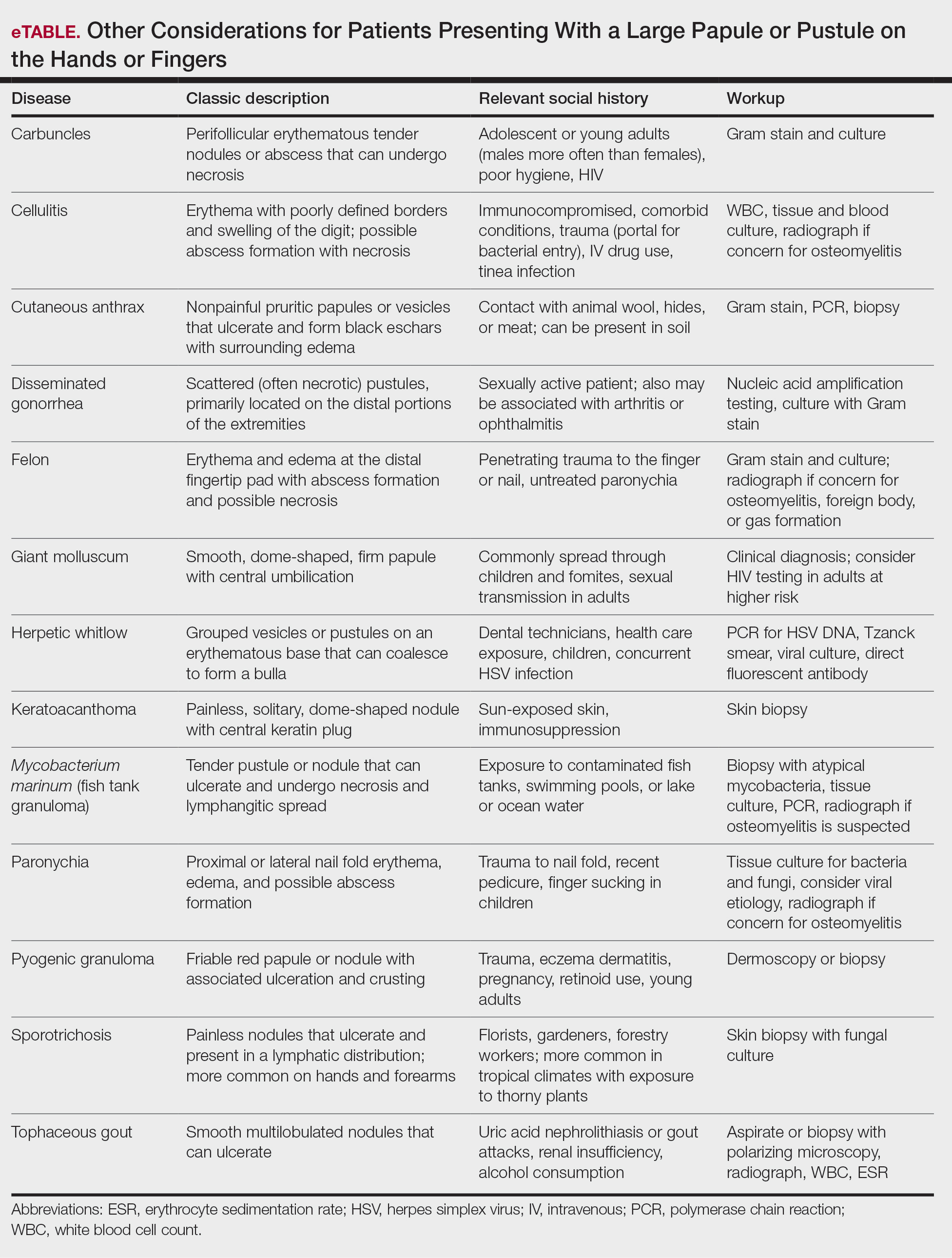

Erythema ab igne is a clinical diagnosis based on recognizable cutaneous findings and a clear history of moderate heat exposure. However, when a clinical diagnosis of EAI is not certain (eg, when unable to obtain a clear history from the patient) or when malignant transformation is suspected, a biopsy can be performed. Pathologically, hematoxylin and eosin staining of EAI classically reveals dilated small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, hence a clinically reticular rash; interface dermatitis clinically manifesting as erythema; and pigment incontinence with melanin-laden macrophages consistent with clinical hyperpigmentation. Finally, for unclear reasons, increased numbers of elastic fibers classically are seen in biopsies of EAI.7

Differential Diagnosis

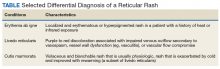

The differential diagnosis for a reticular patch includes livedo reticularis (Figure 3), which usually manifests as a more generalized rash in patients with chronic disease or coagulopathy such as systemic lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia, or Raynaud phenomenon. When differentiating EAI from livedo reticularis or cutis marmorata, consider that both alternative diagnoses are more vascular appearing and are associated with cold exposure rather than heat exposure. In cases that are less reticular, livedo racemosa can be considered in the differential diagnosis. Finally, poikiloderma of Civatte can be reticular, particularly on dermoscopy, but the distribution on the neck with submental sparing should help to distinguish it from EAI unless a heat source around the neck is identified while taking the patient’s history.7

In babies, a reticular generalized rash is most likely to be cutis marmorata (Figure 4), which is a physiologic response to cold exposure that resolves with rewarming of the skin. A more serious condition—cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (Figure 5)—usually is present at birth, most frequently involves a single extremity, and notably does not resolve with rewarming. This is an important differential for EAI in children because it can be associated with vascular and neurologic anomalies as well as limb asymmetry. Finally, port-wine stains can sometimes be reticular in appearance and can mimic the early erythematous stages of EAI. However, unlike the erythematous stage of EAI, the port-wine stains will be present at birth.7

Emerging in 2020, an important differential diagnosis to consider is a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection. An erythematous, reticular, chilblainlike or transient livedo reticularis–like rash has been described as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19. Although the pathophysiology is still being elucidated, it is suspected that this is caused by a major vaso-occlusive crisis secondary to COVID-19–induced thrombotic vasculopathy. Interestingly, the majority of patients with this COVID-related exanthem also displayed symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, cough) at the time of presentation,57-60 but there also have been cases in patients who were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.60

In some cases, EAI is an indication to screen for an underlying disease. For example, uncontrolled pain is an opportunity to improve interventions such as modifying the patient’s pain-control regimen, placing a palliative care pain consultation, or checking if the patient has had age-appropriate screenings for malignancy. New focal pain in a patient with a prior diagnosis of cancer may be a sign of a new metastasis. A thermophilic patient leaves opportunity to assess for underlying medical causes such as thyroid abnormalities or social/psychological issues. Geriatric patients who are diagnosed with EAI may need to be assessed for dementia or home safety issues. Patients with a history of diabetes mellitus can unknowingly develop EAI on the lower extremities, which may signal a need to assess the patient for peripheral neuropathy. Patients with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes also may develop EAI on the abdomen secondary to heating pad use for discomfort. These examples are a reminder to consider possible secondary comorbidities in all diagnoses of EAI.7

Prognosis

Although the prognosis of EAI is excellent if caught early, failure to diagnose this condition can lead to permanent discoloration of the skin and even malignancy.6 A rare sequela includes squamous cell carcinoma, most commonly seen in chronic cases of the lower leg, which is likely related to chronic inflammation of the skin.61-65 Rare cases of poorly differentiated carcinoma,66 cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,67 and Merkel cell carcinoma68 have been reported. Patients diagnosed with EAI should receive normal periodic surveillance of the skin based on their medical history, though the physician should have an increased suspicion and plan for biopsy of any nodules or ulcerations found on the skin of the affected area.7

Treatments

Once the diagnosis of EAI is made, treatment starts with removal of the heat source causing the rash. Because the rash usually is asymptomatic, further treatment typically is not required. The discoloration can resolve over months or years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. If hyperpigmentation persists despite removal of the heat source and the patient desires further treatment for discoloration, there are few treatment options, none of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this condition.7 There is some evidence for the use of Nd:YAG lasers to reduce hyperpigmentation in EAI.69 There have been some reports of treatment using topical hydroquinone and topical tretinoin in an attempt to lighten the skin. If associated hyperkeratosis or other epithelial atypia is present, the use of 5-fluorouracil may show some improvement.70 One case report has been published of successful treatment with systemic mesoglycan and topical bioflavonoids.71 It also is conceivable that medications used to treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be helpful in this condition (eg, kojic acid, arbutin, mild topical steroids, azelaic acid). Patients with darker skin may experience permanent discoloration and may not be good candidates for alternative treatments such as laser therapy due to the risk for inducible hyperpigmentation.7

Conclusion

No matter the etiology, EAI usually is a benign skin condition that is treated by removal of the causative heat source. Once a diagnosis is made, the clinician must work with the patient to determine the etiology. Care must be taken to ensure that there are no underlying signs, such as chronic pain or psychiatric illness, that could point to associated conditions. Rarely, sequalae such as cancers have been documented in areas of chronic EAI. Once the heat source is identified and removed, any remaining hyperpigmentation usually will self-resolve over months to years, though this may take longer in patients with darker skin types. If more aggressive treatment is preferred by the patient, laser therapy, topical medications, and oral over-the-counter vitamins have been tried with minimal responses.

- Perry. Case of erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1900;xxiii:375.

- Bose S, Ortonee JP. Diseases affected by heat. In: Parish LC, Millikan LE, Amer M, et al. Global Dermatology Diagnosis and Management According to Geography, Climate, and Culture. Springer-Varlag; 1994:83-92.

- Leal-Lobato MM, Blasco-Morente G. Electric blanket induced erythema ab igne [in Spanish]. Semergen. 2015;41:456-457. doi:10.1016/j.semerg.2014.12.008

- Huynh N, Sarma D, Huerter C. Erythema ab igne: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:290-292.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. doi:10.5070/D32011024689

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports-related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1569-1594.

- Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: a practical overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0141-6

- Guarneri C, Tchernev G, Wollina U, et al. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:490-492. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.137

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Dickman J, Kessler S. Unilateral reticulated patch localized to the anterior thigh. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.06.007

- Boffa MJ. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne on the left breast. Cutis. 2011;87:175-176.

- Li K, Barankin B. Cutaneous manifestations of modern technology use. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:347-353. doi:10.2310/7750.2011.10053

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Andersen F. Laptop-thighs--laptop-induced erythema ab igne [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:635.

- Jagtman BA. Erythema ab igne due to a laptop computer. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:105. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.0295g.x

- Olechowska M, Kisiel K, Ruszkowska L, et al. Erythema ab igne (EAI) induced by a laptop computer: report of two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2014.12387

- Nayak SUK, Shenoi SD, Prabhu S. Laptop induced erythema ab igne. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:131-132. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94284

- Salvio AG, Nunes AJ, Angarita DPR. Laptop computer induced erythema ab igne: a new presentation of an old disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:79-80. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165139

- Schummer C, Tittelbach J, Elsner P. Right-sided laptop dermatitis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:1376-1377. doi:10.1055/s-0041-103615

- Manoharan D. Erythema ab igne: usual site, unusual cause. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 1):S74-S75. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.155811

- Giraldi S, Diettrich F, Abbage KT, et al. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer in an adolescent. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:128-130. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962011000100018

- Secher LLS, Vind-Kezunovic D, Zachariae COC. Side-effects to the use of laptop computers: erythema ab igne. Dermatol Reports. 2010;31:E11. doi:10.4081/dr.2010.e11

- Botten D, Langley RGB, Webb A. Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers. CMAJ. 2010;182:E857. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091868

- Bilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.08.007

- Fu LW, Vender R. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer gaming - a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:716-717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05033.x

- Levinbook WS, Mallett J, Grant-Kels JM. Laptop computer-associated erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2007;80:319-320.

- Mohr MR, Scott KA, Pariser RM, et al. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:59-60.

- Cantor AS, Bartling SJ. Laptop computer-induced hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6k37r9wm.

- Kaptanog˘lu AF, Mullaaziz D. Erythema ab igne in the palmar area induced by smart phone: case report. Turkiye Klin J Med Sci. 2015;35:284-286. doi:10.5336/medsci.2015-46976

- Redding KS, Watts AN, Lee J, et al. Space heater-induced bullous erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2017;100:E9-E10.

- Goorland J, Edens MA, Baudoin TD. An emergency department presentation of erythema ab igne caused by repeated heater exposure. J La State Med Soc. 2016;168:33-34.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Brzezinski P, Ismail S, Chiriac A. Radiator-induced erythema ab igne in 8-year-old girl. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014;85:239-240. doi:10.4067/S0370-41062014000200015

- Adams BB. Heated car seat-induced erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:265-266. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2207

- Helm TN, Spigel GT, Helm KF. Erythema ab igne caused by a car heater. Cutis. 1997;59:81-82.

- Gregory JF, Beute TC. Erythema ab igne. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13:115-119. doi:10.55460/5AVH-NZHY

- Chua S, Chen Q, Lee HY. Erythema ab igne and dermal scarring caused by cupping and moxibustion treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:337-338. doi:10.1111/ddg.12581

- Chen JF, Liu YC, Chen YF, et al. Erythema ab igne after footbath with Chinese herbal remedies. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2011;74:51-53. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2011.01.009

- Baltazar D, Brockman R, Simpson E. Kotatsu-induced erythema ab igne. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:253-254. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198792

- Baig M, Byrne F. Erythema ab igne and its relation to spinal pathology. Cureus. 2018;10:e2914. doi:10.7759/cureus.2914

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:e2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:e236-e238. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001460

- Dizdarevic A, Karim OA, Bygum A. A reddish brown reticulated hyperpigmented erythema on the abdomen of a girl. Erythema ab igne, also known as toasted skin syndrome, caused by a heating pad onthe abdomen. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:365-367. doi:10.2340/00015555-1722

- Chatterjee S. Erythema ab igne from prolonged use of a heating pad. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1500. doi:10.4065/80.11.1500

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis “erythema ab igne.” JAMA. 1971;218:1704. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190240056023

- South AM, Crispin MK, Marqueling AL, et al. A hyperpigmented reticular rash in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:677-700. doi:10.3747/pdi.2016.00042

- Ravindran R. Erythema ab igne in an individual with diabetes and gastroparesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2014203856. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203856

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Tzavela E, et al. Erythema ab igne in three girls with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e149-e150. doi:10.1111/pde.12770

- Fischer J, Rein K, Erfurt-Berge C, et al. Three cases of erythema ab igne (EAI) in patients with eating disorders. Neuropsychiatr. 2010;24:141-143.

- Docx MKF, Simons A, Ramet J, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:381-383. doi:10.1002/eat.22075

- Turan E, Cimen V, Haytoglu NSK, et al. A case of bullous erythema ab igne accompanied by anemia and subclinical hypothyroidism. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:223366.

- Pavithran K. Erythema ab igne, schizophrenia and thermophilia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:181-182.

- Dellavelle R, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Park SY, Kim SM, Yoon TJ. Erythema ab igne caused by weight loss heating pad. Korean J Dermatol. 2007;45:489-491.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Gisondi P, Plaserico S, Bordin C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2499-2504. doi:10.1111/jdv.16774

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:700. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018

- Zhao Q, Fang X, Pang Z, et al. COVID‐19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2505-2510. doi:10.1111/jdv.16778

- Akasaka T, Kon S. Two cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising from erythema ab igne. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;99:735-742.

- Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1226-1228.

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Wollina U, Helm C, Hansel G, et al. Two cases of erythema ab igne, one with a squamous cell carcinoma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2007;142:415-418.

- Rudolph CM, Soyer HP, Wolf P, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in erythema ab igne. Hautarzt. 2000;51:260-263. doi:10.1007/s001050051115

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:147-148. doi:10.3109/14764172.2013.854623

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;62:77-78.

- Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:432-435. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.123

Erythema ab igne (EAI)(also known as toasted skin syndrome) was first described in the British Journal of Dermatology in the 20th century, 1 though it was known by physicians long before. Reticular netlike skin changes were seen in association with patients who spent extended time directly next to a heat source. This association led to the name of this condition, which literally means “redness by fire.” Indeed, EAI induced by chronic heat exposure has been described across the world for centuries. For example, in the cold regions of northern China, people used to sleep on beds of hot bricks called kang to stay warm at night. The people of India’s Kashmir district carried pots of hot coals called kangri next to the skin under large woven shawls to stay warm. In the past, Irish women often spent much time by a turf- or peat-burning fire. Chronic heat exposure in these cases can lead not only to EAI but also to aggressive types of cancer, often with a latency of 30 years or more. 2

More recently, the invention of home central heating led to a stark decrease in the number of cases associated with combustion-based heat, with a transition to etiologies such as use of hot water bottles, electric blankets, and electric space heaters. Over time, technological advances led to ever-increasing potential causes for EAI, such as laptops or cell phones, car heaters and heated seats, heated blankets,3,4 infrared lamps for food, and even medical devices such as ultrasound-based heating products and convective temperature management systems for hospitalized patients. As technology evolves, so do the potential causes of EAI, requiring clinicians to diagnose and deduce the cause through a thorough social and medical history as well as a workup on the present illness with considerations for the anatomical location.5-7 Herein, we describe the etiology of EAI, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Clinical Characteristics

Erythema ab igne begins as mild, transient, and erythematous macules and patches in a reticular pattern that resolve minutes to hours after removal of the heat source. With weeks to months of continued or repeated application of the heat source, the affected area eventually becomes hyperpigmented where there once was erythema (Figures 1 and 2). Sometimes papules, bullae, telangiectasia, and hyperkeratosis also form. The rash usually is asymptomatic, though pain, pruritus, and dysesthesia have been reported.7 Dermoscopy of EAI in the hyperpigmented stage can reveal diffuse superficial dark pigmentation, telangiectasia, and mild whitish scaling.8 Although the pathogenesis has remained elusive over the years, lesions do seem to be mostly associated with cumulative exposure to heat rather than length of exposure.7

Etiology of EAI

Anatomic Location—The affected site depends on the source of heat (Table). Classic examples of this condition include a patient with EAI presenting on the anterior thighs after working in front of a hot oven or a patient with chronic back pain presenting with lower-back EAI secondary to frequent use of a hot water bottle or heating pad.7 With evolving technology over the last few decades, new etiologies have become more common—teenagers are presenting with anterior thigh EAI secondary to frequent laptop use2-29; patients are holding warm cell phones in their pant pockets, leading to unilateral geometric EAI on the anterior thigh (front pocket) or buttock (back pocket)30; plug-in radiators under computer desks are causing EAI on the lower legs31-34; and automobile seat heaters have been shown to cause EAI on the posterior legs.5,35-37 Clinicians should consider anatomic location a critical clue for etiology.

Social History—There are rarer and more highly specific causes of EAI than simple heat exposure that can be parsed from a patient’s social history. Occupational exposure has been documented, such as bakers with exposure to ovens, foundry workers with exposure to heated metals, or fast-food workers with chronic exposure to infrared food lamps.6,7 There also are cultural practices that can cause EAI. For example, the practice of cupping with moxibustion was shown to create a specific pattern in the shape of the cultural tool used.38 When footbaths with Chinese herbal remedies are performed frequently with high heat, they can lead to EAI on the feet with a linear border at the ankles. There also have been reports of kotatsu (heated tables in Japan) leading to lower-body EAI.39,40 These cultural practices also are more common in patients with darker skin types, which can lead to hyperpigmentation that is difficult to treat, making early diagnosis important.7

Medical History—Case reports have shown EAI caused by patients attempting to use heat-based methods for pain relief of an underlying serious disease such as cancer, bowel pathology (abdominal EAI), spinal disc prolapse (midline back EAI),41 sickle cell anemia, and renal pathology (posterior upper flank EAI).6,7,40-49 Patients with hypothyroidism or anorexia have been noted to have generalized EAI sparing the face secondary to repeated and extended hot baths or showers.50-53 One patient with schizophrenia was shown to have associated thermophilia due to a delusion that led the patient to soak in hot baths for long periods of time, leading to EAI.54 Finally, all physicians should be aware of iatrogenic causes of EAI, such as use of warming devices, ultrasound-based warming techniques, and laser therapy for lipolysis. Inquire about the patient’s surgical history or intensive care unit stays as well as alternative medicine or chiropractic visits. Obtaining a history of medical procedures can be enlightening when an etiology is not immediately clear.7,55,56

Diagnosis

Erythema ab igne is a clinical diagnosis based on recognizable cutaneous findings and a clear history of moderate heat exposure. However, when a clinical diagnosis of EAI is not certain (eg, when unable to obtain a clear history from the patient) or when malignant transformation is suspected, a biopsy can be performed. Pathologically, hematoxylin and eosin staining of EAI classically reveals dilated small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, hence a clinically reticular rash; interface dermatitis clinically manifesting as erythema; and pigment incontinence with melanin-laden macrophages consistent with clinical hyperpigmentation. Finally, for unclear reasons, increased numbers of elastic fibers classically are seen in biopsies of EAI.7

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a reticular patch includes livedo reticularis (Figure 3), which usually manifests as a more generalized rash in patients with chronic disease or coagulopathy such as systemic lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia, or Raynaud phenomenon. When differentiating EAI from livedo reticularis or cutis marmorata, consider that both alternative diagnoses are more vascular appearing and are associated with cold exposure rather than heat exposure. In cases that are less reticular, livedo racemosa can be considered in the differential diagnosis. Finally, poikiloderma of Civatte can be reticular, particularly on dermoscopy, but the distribution on the neck with submental sparing should help to distinguish it from EAI unless a heat source around the neck is identified while taking the patient’s history.7

In babies, a reticular generalized rash is most likely to be cutis marmorata (Figure 4), which is a physiologic response to cold exposure that resolves with rewarming of the skin. A more serious condition—cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (Figure 5)—usually is present at birth, most frequently involves a single extremity, and notably does not resolve with rewarming. This is an important differential for EAI in children because it can be associated with vascular and neurologic anomalies as well as limb asymmetry. Finally, port-wine stains can sometimes be reticular in appearance and can mimic the early erythematous stages of EAI. However, unlike the erythematous stage of EAI, the port-wine stains will be present at birth.7

Emerging in 2020, an important differential diagnosis to consider is a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection. An erythematous, reticular, chilblainlike or transient livedo reticularis–like rash has been described as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19. Although the pathophysiology is still being elucidated, it is suspected that this is caused by a major vaso-occlusive crisis secondary to COVID-19–induced thrombotic vasculopathy. Interestingly, the majority of patients with this COVID-related exanthem also displayed symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, cough) at the time of presentation,57-60 but there also have been cases in patients who were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.60

In some cases, EAI is an indication to screen for an underlying disease. For example, uncontrolled pain is an opportunity to improve interventions such as modifying the patient’s pain-control regimen, placing a palliative care pain consultation, or checking if the patient has had age-appropriate screenings for malignancy. New focal pain in a patient with a prior diagnosis of cancer may be a sign of a new metastasis. A thermophilic patient leaves opportunity to assess for underlying medical causes such as thyroid abnormalities or social/psychological issues. Geriatric patients who are diagnosed with EAI may need to be assessed for dementia or home safety issues. Patients with a history of diabetes mellitus can unknowingly develop EAI on the lower extremities, which may signal a need to assess the patient for peripheral neuropathy. Patients with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes also may develop EAI on the abdomen secondary to heating pad use for discomfort. These examples are a reminder to consider possible secondary comorbidities in all diagnoses of EAI.7

Prognosis

Although the prognosis of EAI is excellent if caught early, failure to diagnose this condition can lead to permanent discoloration of the skin and even malignancy.6 A rare sequela includes squamous cell carcinoma, most commonly seen in chronic cases of the lower leg, which is likely related to chronic inflammation of the skin.61-65 Rare cases of poorly differentiated carcinoma,66 cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,67 and Merkel cell carcinoma68 have been reported. Patients diagnosed with EAI should receive normal periodic surveillance of the skin based on their medical history, though the physician should have an increased suspicion and plan for biopsy of any nodules or ulcerations found on the skin of the affected area.7

Treatments

Once the diagnosis of EAI is made, treatment starts with removal of the heat source causing the rash. Because the rash usually is asymptomatic, further treatment typically is not required. The discoloration can resolve over months or years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. If hyperpigmentation persists despite removal of the heat source and the patient desires further treatment for discoloration, there are few treatment options, none of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this condition.7 There is some evidence for the use of Nd:YAG lasers to reduce hyperpigmentation in EAI.69 There have been some reports of treatment using topical hydroquinone and topical tretinoin in an attempt to lighten the skin. If associated hyperkeratosis or other epithelial atypia is present, the use of 5-fluorouracil may show some improvement.70 One case report has been published of successful treatment with systemic mesoglycan and topical bioflavonoids.71 It also is conceivable that medications used to treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be helpful in this condition (eg, kojic acid, arbutin, mild topical steroids, azelaic acid). Patients with darker skin may experience permanent discoloration and may not be good candidates for alternative treatments such as laser therapy due to the risk for inducible hyperpigmentation.7

Conclusion

No matter the etiology, EAI usually is a benign skin condition that is treated by removal of the causative heat source. Once a diagnosis is made, the clinician must work with the patient to determine the etiology. Care must be taken to ensure that there are no underlying signs, such as chronic pain or psychiatric illness, that could point to associated conditions. Rarely, sequalae such as cancers have been documented in areas of chronic EAI. Once the heat source is identified and removed, any remaining hyperpigmentation usually will self-resolve over months to years, though this may take longer in patients with darker skin types. If more aggressive treatment is preferred by the patient, laser therapy, topical medications, and oral over-the-counter vitamins have been tried with minimal responses.

Erythema ab igne (EAI)(also known as toasted skin syndrome) was first described in the British Journal of Dermatology in the 20th century, 1 though it was known by physicians long before. Reticular netlike skin changes were seen in association with patients who spent extended time directly next to a heat source. This association led to the name of this condition, which literally means “redness by fire.” Indeed, EAI induced by chronic heat exposure has been described across the world for centuries. For example, in the cold regions of northern China, people used to sleep on beds of hot bricks called kang to stay warm at night. The people of India’s Kashmir district carried pots of hot coals called kangri next to the skin under large woven shawls to stay warm. In the past, Irish women often spent much time by a turf- or peat-burning fire. Chronic heat exposure in these cases can lead not only to EAI but also to aggressive types of cancer, often with a latency of 30 years or more. 2

More recently, the invention of home central heating led to a stark decrease in the number of cases associated with combustion-based heat, with a transition to etiologies such as use of hot water bottles, electric blankets, and electric space heaters. Over time, technological advances led to ever-increasing potential causes for EAI, such as laptops or cell phones, car heaters and heated seats, heated blankets,3,4 infrared lamps for food, and even medical devices such as ultrasound-based heating products and convective temperature management systems for hospitalized patients. As technology evolves, so do the potential causes of EAI, requiring clinicians to diagnose and deduce the cause through a thorough social and medical history as well as a workup on the present illness with considerations for the anatomical location.5-7 Herein, we describe the etiology of EAI, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Clinical Characteristics

Erythema ab igne begins as mild, transient, and erythematous macules and patches in a reticular pattern that resolve minutes to hours after removal of the heat source. With weeks to months of continued or repeated application of the heat source, the affected area eventually becomes hyperpigmented where there once was erythema (Figures 1 and 2). Sometimes papules, bullae, telangiectasia, and hyperkeratosis also form. The rash usually is asymptomatic, though pain, pruritus, and dysesthesia have been reported.7 Dermoscopy of EAI in the hyperpigmented stage can reveal diffuse superficial dark pigmentation, telangiectasia, and mild whitish scaling.8 Although the pathogenesis has remained elusive over the years, lesions do seem to be mostly associated with cumulative exposure to heat rather than length of exposure.7

Etiology of EAI

Anatomic Location—The affected site depends on the source of heat (Table). Classic examples of this condition include a patient with EAI presenting on the anterior thighs after working in front of a hot oven or a patient with chronic back pain presenting with lower-back EAI secondary to frequent use of a hot water bottle or heating pad.7 With evolving technology over the last few decades, new etiologies have become more common—teenagers are presenting with anterior thigh EAI secondary to frequent laptop use2-29; patients are holding warm cell phones in their pant pockets, leading to unilateral geometric EAI on the anterior thigh (front pocket) or buttock (back pocket)30; plug-in radiators under computer desks are causing EAI on the lower legs31-34; and automobile seat heaters have been shown to cause EAI on the posterior legs.5,35-37 Clinicians should consider anatomic location a critical clue for etiology.

Social History—There are rarer and more highly specific causes of EAI than simple heat exposure that can be parsed from a patient’s social history. Occupational exposure has been documented, such as bakers with exposure to ovens, foundry workers with exposure to heated metals, or fast-food workers with chronic exposure to infrared food lamps.6,7 There also are cultural practices that can cause EAI. For example, the practice of cupping with moxibustion was shown to create a specific pattern in the shape of the cultural tool used.38 When footbaths with Chinese herbal remedies are performed frequently with high heat, they can lead to EAI on the feet with a linear border at the ankles. There also have been reports of kotatsu (heated tables in Japan) leading to lower-body EAI.39,40 These cultural practices also are more common in patients with darker skin types, which can lead to hyperpigmentation that is difficult to treat, making early diagnosis important.7

Medical History—Case reports have shown EAI caused by patients attempting to use heat-based methods for pain relief of an underlying serious disease such as cancer, bowel pathology (abdominal EAI), spinal disc prolapse (midline back EAI),41 sickle cell anemia, and renal pathology (posterior upper flank EAI).6,7,40-49 Patients with hypothyroidism or anorexia have been noted to have generalized EAI sparing the face secondary to repeated and extended hot baths or showers.50-53 One patient with schizophrenia was shown to have associated thermophilia due to a delusion that led the patient to soak in hot baths for long periods of time, leading to EAI.54 Finally, all physicians should be aware of iatrogenic causes of EAI, such as use of warming devices, ultrasound-based warming techniques, and laser therapy for lipolysis. Inquire about the patient’s surgical history or intensive care unit stays as well as alternative medicine or chiropractic visits. Obtaining a history of medical procedures can be enlightening when an etiology is not immediately clear.7,55,56

Diagnosis

Erythema ab igne is a clinical diagnosis based on recognizable cutaneous findings and a clear history of moderate heat exposure. However, when a clinical diagnosis of EAI is not certain (eg, when unable to obtain a clear history from the patient) or when malignant transformation is suspected, a biopsy can be performed. Pathologically, hematoxylin and eosin staining of EAI classically reveals dilated small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, hence a clinically reticular rash; interface dermatitis clinically manifesting as erythema; and pigment incontinence with melanin-laden macrophages consistent with clinical hyperpigmentation. Finally, for unclear reasons, increased numbers of elastic fibers classically are seen in biopsies of EAI.7

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a reticular patch includes livedo reticularis (Figure 3), which usually manifests as a more generalized rash in patients with chronic disease or coagulopathy such as systemic lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia, or Raynaud phenomenon. When differentiating EAI from livedo reticularis or cutis marmorata, consider that both alternative diagnoses are more vascular appearing and are associated with cold exposure rather than heat exposure. In cases that are less reticular, livedo racemosa can be considered in the differential diagnosis. Finally, poikiloderma of Civatte can be reticular, particularly on dermoscopy, but the distribution on the neck with submental sparing should help to distinguish it from EAI unless a heat source around the neck is identified while taking the patient’s history.7

In babies, a reticular generalized rash is most likely to be cutis marmorata (Figure 4), which is a physiologic response to cold exposure that resolves with rewarming of the skin. A more serious condition—cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (Figure 5)—usually is present at birth, most frequently involves a single extremity, and notably does not resolve with rewarming. This is an important differential for EAI in children because it can be associated with vascular and neurologic anomalies as well as limb asymmetry. Finally, port-wine stains can sometimes be reticular in appearance and can mimic the early erythematous stages of EAI. However, unlike the erythematous stage of EAI, the port-wine stains will be present at birth.7

Emerging in 2020, an important differential diagnosis to consider is a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection. An erythematous, reticular, chilblainlike or transient livedo reticularis–like rash has been described as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19. Although the pathophysiology is still being elucidated, it is suspected that this is caused by a major vaso-occlusive crisis secondary to COVID-19–induced thrombotic vasculopathy. Interestingly, the majority of patients with this COVID-related exanthem also displayed symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, cough) at the time of presentation,57-60 but there also have been cases in patients who were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.60

In some cases, EAI is an indication to screen for an underlying disease. For example, uncontrolled pain is an opportunity to improve interventions such as modifying the patient’s pain-control regimen, placing a palliative care pain consultation, or checking if the patient has had age-appropriate screenings for malignancy. New focal pain in a patient with a prior diagnosis of cancer may be a sign of a new metastasis. A thermophilic patient leaves opportunity to assess for underlying medical causes such as thyroid abnormalities or social/psychological issues. Geriatric patients who are diagnosed with EAI may need to be assessed for dementia or home safety issues. Patients with a history of diabetes mellitus can unknowingly develop EAI on the lower extremities, which may signal a need to assess the patient for peripheral neuropathy. Patients with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes also may develop EAI on the abdomen secondary to heating pad use for discomfort. These examples are a reminder to consider possible secondary comorbidities in all diagnoses of EAI.7

Prognosis

Although the prognosis of EAI is excellent if caught early, failure to diagnose this condition can lead to permanent discoloration of the skin and even malignancy.6 A rare sequela includes squamous cell carcinoma, most commonly seen in chronic cases of the lower leg, which is likely related to chronic inflammation of the skin.61-65 Rare cases of poorly differentiated carcinoma,66 cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,67 and Merkel cell carcinoma68 have been reported. Patients diagnosed with EAI should receive normal periodic surveillance of the skin based on their medical history, though the physician should have an increased suspicion and plan for biopsy of any nodules or ulcerations found on the skin of the affected area.7

Treatments

Once the diagnosis of EAI is made, treatment starts with removal of the heat source causing the rash. Because the rash usually is asymptomatic, further treatment typically is not required. The discoloration can resolve over months or years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. If hyperpigmentation persists despite removal of the heat source and the patient desires further treatment for discoloration, there are few treatment options, none of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this condition.7 There is some evidence for the use of Nd:YAG lasers to reduce hyperpigmentation in EAI.69 There have been some reports of treatment using topical hydroquinone and topical tretinoin in an attempt to lighten the skin. If associated hyperkeratosis or other epithelial atypia is present, the use of 5-fluorouracil may show some improvement.70 One case report has been published of successful treatment with systemic mesoglycan and topical bioflavonoids.71 It also is conceivable that medications used to treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be helpful in this condition (eg, kojic acid, arbutin, mild topical steroids, azelaic acid). Patients with darker skin may experience permanent discoloration and may not be good candidates for alternative treatments such as laser therapy due to the risk for inducible hyperpigmentation.7

Conclusion

No matter the etiology, EAI usually is a benign skin condition that is treated by removal of the causative heat source. Once a diagnosis is made, the clinician must work with the patient to determine the etiology. Care must be taken to ensure that there are no underlying signs, such as chronic pain or psychiatric illness, that could point to associated conditions. Rarely, sequalae such as cancers have been documented in areas of chronic EAI. Once the heat source is identified and removed, any remaining hyperpigmentation usually will self-resolve over months to years, though this may take longer in patients with darker skin types. If more aggressive treatment is preferred by the patient, laser therapy, topical medications, and oral over-the-counter vitamins have been tried with minimal responses.

- Perry. Case of erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1900;xxiii:375.

- Bose S, Ortonee JP. Diseases affected by heat. In: Parish LC, Millikan LE, Amer M, et al. Global Dermatology Diagnosis and Management According to Geography, Climate, and Culture. Springer-Varlag; 1994:83-92.

- Leal-Lobato MM, Blasco-Morente G. Electric blanket induced erythema ab igne [in Spanish]. Semergen. 2015;41:456-457. doi:10.1016/j.semerg.2014.12.008

- Huynh N, Sarma D, Huerter C. Erythema ab igne: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:290-292.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. doi:10.5070/D32011024689

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports-related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1569-1594.

- Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: a practical overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0141-6

- Guarneri C, Tchernev G, Wollina U, et al. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:490-492. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.137

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Dickman J, Kessler S. Unilateral reticulated patch localized to the anterior thigh. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.06.007

- Boffa MJ. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne on the left breast. Cutis. 2011;87:175-176.

- Li K, Barankin B. Cutaneous manifestations of modern technology use. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:347-353. doi:10.2310/7750.2011.10053

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Andersen F. Laptop-thighs--laptop-induced erythema ab igne [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:635.

- Jagtman BA. Erythema ab igne due to a laptop computer. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:105. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.0295g.x

- Olechowska M, Kisiel K, Ruszkowska L, et al. Erythema ab igne (EAI) induced by a laptop computer: report of two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2014.12387

- Nayak SUK, Shenoi SD, Prabhu S. Laptop induced erythema ab igne. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:131-132. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94284

- Salvio AG, Nunes AJ, Angarita DPR. Laptop computer induced erythema ab igne: a new presentation of an old disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:79-80. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165139

- Schummer C, Tittelbach J, Elsner P. Right-sided laptop dermatitis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:1376-1377. doi:10.1055/s-0041-103615

- Manoharan D. Erythema ab igne: usual site, unusual cause. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 1):S74-S75. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.155811

- Giraldi S, Diettrich F, Abbage KT, et al. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer in an adolescent. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:128-130. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962011000100018

- Secher LLS, Vind-Kezunovic D, Zachariae COC. Side-effects to the use of laptop computers: erythema ab igne. Dermatol Reports. 2010;31:E11. doi:10.4081/dr.2010.e11

- Botten D, Langley RGB, Webb A. Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers. CMAJ. 2010;182:E857. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091868

- Bilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.08.007

- Fu LW, Vender R. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer gaming - a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:716-717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05033.x

- Levinbook WS, Mallett J, Grant-Kels JM. Laptop computer-associated erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2007;80:319-320.

- Mohr MR, Scott KA, Pariser RM, et al. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:59-60.

- Cantor AS, Bartling SJ. Laptop computer-induced hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6k37r9wm.

- Kaptanog˘lu AF, Mullaaziz D. Erythema ab igne in the palmar area induced by smart phone: case report. Turkiye Klin J Med Sci. 2015;35:284-286. doi:10.5336/medsci.2015-46976

- Redding KS, Watts AN, Lee J, et al. Space heater-induced bullous erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2017;100:E9-E10.

- Goorland J, Edens MA, Baudoin TD. An emergency department presentation of erythema ab igne caused by repeated heater exposure. J La State Med Soc. 2016;168:33-34.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Brzezinski P, Ismail S, Chiriac A. Radiator-induced erythema ab igne in 8-year-old girl. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014;85:239-240. doi:10.4067/S0370-41062014000200015

- Adams BB. Heated car seat-induced erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:265-266. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2207

- Helm TN, Spigel GT, Helm KF. Erythema ab igne caused by a car heater. Cutis. 1997;59:81-82.

- Gregory JF, Beute TC. Erythema ab igne. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13:115-119. doi:10.55460/5AVH-NZHY

- Chua S, Chen Q, Lee HY. Erythema ab igne and dermal scarring caused by cupping and moxibustion treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:337-338. doi:10.1111/ddg.12581

- Chen JF, Liu YC, Chen YF, et al. Erythema ab igne after footbath with Chinese herbal remedies. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2011;74:51-53. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2011.01.009

- Baltazar D, Brockman R, Simpson E. Kotatsu-induced erythema ab igne. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:253-254. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198792

- Baig M, Byrne F. Erythema ab igne and its relation to spinal pathology. Cureus. 2018;10:e2914. doi:10.7759/cureus.2914

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:e2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:e236-e238. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001460

- Dizdarevic A, Karim OA, Bygum A. A reddish brown reticulated hyperpigmented erythema on the abdomen of a girl. Erythema ab igne, also known as toasted skin syndrome, caused by a heating pad onthe abdomen. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:365-367. doi:10.2340/00015555-1722

- Chatterjee S. Erythema ab igne from prolonged use of a heating pad. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1500. doi:10.4065/80.11.1500

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis “erythema ab igne.” JAMA. 1971;218:1704. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190240056023

- South AM, Crispin MK, Marqueling AL, et al. A hyperpigmented reticular rash in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:677-700. doi:10.3747/pdi.2016.00042

- Ravindran R. Erythema ab igne in an individual with diabetes and gastroparesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2014203856. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203856

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Tzavela E, et al. Erythema ab igne in three girls with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e149-e150. doi:10.1111/pde.12770

- Fischer J, Rein K, Erfurt-Berge C, et al. Three cases of erythema ab igne (EAI) in patients with eating disorders. Neuropsychiatr. 2010;24:141-143.

- Docx MKF, Simons A, Ramet J, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:381-383. doi:10.1002/eat.22075

- Turan E, Cimen V, Haytoglu NSK, et al. A case of bullous erythema ab igne accompanied by anemia and subclinical hypothyroidism. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:223366.

- Pavithran K. Erythema ab igne, schizophrenia and thermophilia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:181-182.

- Dellavelle R, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Park SY, Kim SM, Yoon TJ. Erythema ab igne caused by weight loss heating pad. Korean J Dermatol. 2007;45:489-491.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Gisondi P, Plaserico S, Bordin C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2499-2504. doi:10.1111/jdv.16774

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:700. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018

- Zhao Q, Fang X, Pang Z, et al. COVID‐19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2505-2510. doi:10.1111/jdv.16778

- Akasaka T, Kon S. Two cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising from erythema ab igne. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;99:735-742.

- Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1226-1228.

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Wollina U, Helm C, Hansel G, et al. Two cases of erythema ab igne, one with a squamous cell carcinoma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2007;142:415-418.

- Rudolph CM, Soyer HP, Wolf P, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in erythema ab igne. Hautarzt. 2000;51:260-263. doi:10.1007/s001050051115

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:147-148. doi:10.3109/14764172.2013.854623

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;62:77-78.

- Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:432-435. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.123

- Perry. Case of erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1900;xxiii:375.

- Bose S, Ortonee JP. Diseases affected by heat. In: Parish LC, Millikan LE, Amer M, et al. Global Dermatology Diagnosis and Management According to Geography, Climate, and Culture. Springer-Varlag; 1994:83-92.

- Leal-Lobato MM, Blasco-Morente G. Electric blanket induced erythema ab igne [in Spanish]. Semergen. 2015;41:456-457. doi:10.1016/j.semerg.2014.12.008

- Huynh N, Sarma D, Huerter C. Erythema ab igne: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:290-292.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. doi:10.5070/D32011024689

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports-related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1569-1594.

- Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: a practical overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0141-6

- Guarneri C, Tchernev G, Wollina U, et al. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:490-492. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.137

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Dickman J, Kessler S. Unilateral reticulated patch localized to the anterior thigh. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.06.007

- Boffa MJ. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne on the left breast. Cutis. 2011;87:175-176.

- Li K, Barankin B. Cutaneous manifestations of modern technology use. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:347-353. doi:10.2310/7750.2011.10053

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Andersen F. Laptop-thighs--laptop-induced erythema ab igne [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:635.

- Jagtman BA. Erythema ab igne due to a laptop computer. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:105. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.0295g.x

- Olechowska M, Kisiel K, Ruszkowska L, et al. Erythema ab igne (EAI) induced by a laptop computer: report of two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2014.12387

- Nayak SUK, Shenoi SD, Prabhu S. Laptop induced erythema ab igne. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:131-132. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94284

- Salvio AG, Nunes AJ, Angarita DPR. Laptop computer induced erythema ab igne: a new presentation of an old disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:79-80. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165139

- Schummer C, Tittelbach J, Elsner P. Right-sided laptop dermatitis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:1376-1377. doi:10.1055/s-0041-103615

- Manoharan D. Erythema ab igne: usual site, unusual cause. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 1):S74-S75. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.155811

- Giraldi S, Diettrich F, Abbage KT, et al. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer in an adolescent. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:128-130. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962011000100018

- Secher LLS, Vind-Kezunovic D, Zachariae COC. Side-effects to the use of laptop computers: erythema ab igne. Dermatol Reports. 2010;31:E11. doi:10.4081/dr.2010.e11

- Botten D, Langley RGB, Webb A. Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers. CMAJ. 2010;182:E857. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091868

- Bilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.08.007

- Fu LW, Vender R. Erythema ab igne caused by laptop computer gaming - a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:716-717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05033.x

- Levinbook WS, Mallett J, Grant-Kels JM. Laptop computer-associated erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2007;80:319-320.

- Mohr MR, Scott KA, Pariser RM, et al. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:59-60.

- Cantor AS, Bartling SJ. Laptop computer-induced hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6k37r9wm.

- Kaptanog˘lu AF, Mullaaziz D. Erythema ab igne in the palmar area induced by smart phone: case report. Turkiye Klin J Med Sci. 2015;35:284-286. doi:10.5336/medsci.2015-46976

- Redding KS, Watts AN, Lee J, et al. Space heater-induced bullous erythema ab igne. Cutis. 2017;100:E9-E10.

- Goorland J, Edens MA, Baudoin TD. An emergency department presentation of erythema ab igne caused by repeated heater exposure. J La State Med Soc. 2016;168:33-34.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Brzezinski P, Ismail S, Chiriac A. Radiator-induced erythema ab igne in 8-year-old girl. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014;85:239-240. doi:10.4067/S0370-41062014000200015

- Adams BB. Heated car seat-induced erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:265-266. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2207

- Helm TN, Spigel GT, Helm KF. Erythema ab igne caused by a car heater. Cutis. 1997;59:81-82.

- Gregory JF, Beute TC. Erythema ab igne. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13:115-119. doi:10.55460/5AVH-NZHY

- Chua S, Chen Q, Lee HY. Erythema ab igne and dermal scarring caused by cupping and moxibustion treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:337-338. doi:10.1111/ddg.12581

- Chen JF, Liu YC, Chen YF, et al. Erythema ab igne after footbath with Chinese herbal remedies. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2011;74:51-53. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2011.01.009

- Baltazar D, Brockman R, Simpson E. Kotatsu-induced erythema ab igne. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:253-254. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198792

- Baig M, Byrne F. Erythema ab igne and its relation to spinal pathology. Cureus. 2018;10:e2914. doi:10.7759/cureus.2914

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:e2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:e236-e238. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001460

- Dizdarevic A, Karim OA, Bygum A. A reddish brown reticulated hyperpigmented erythema on the abdomen of a girl. Erythema ab igne, also known as toasted skin syndrome, caused by a heating pad onthe abdomen. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:365-367. doi:10.2340/00015555-1722

- Chatterjee S. Erythema ab igne from prolonged use of a heating pad. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1500. doi:10.4065/80.11.1500

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis “erythema ab igne.” JAMA. 1971;218:1704. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190240056023

- South AM, Crispin MK, Marqueling AL, et al. A hyperpigmented reticular rash in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:677-700. doi:10.3747/pdi.2016.00042

- Ravindran R. Erythema ab igne in an individual with diabetes and gastroparesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2014203856. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203856

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Tzavela E, et al. Erythema ab igne in three girls with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e149-e150. doi:10.1111/pde.12770

- Fischer J, Rein K, Erfurt-Berge C, et al. Three cases of erythema ab igne (EAI) in patients with eating disorders. Neuropsychiatr. 2010;24:141-143.

- Docx MKF, Simons A, Ramet J, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:381-383. doi:10.1002/eat.22075

- Turan E, Cimen V, Haytoglu NSK, et al. A case of bullous erythema ab igne accompanied by anemia and subclinical hypothyroidism. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:223366.

- Pavithran K. Erythema ab igne, schizophrenia and thermophilia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:181-182.

- Dellavelle R, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Park SY, Kim SM, Yoon TJ. Erythema ab igne caused by weight loss heating pad. Korean J Dermatol. 2007;45:489-491.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Gisondi P, Plaserico S, Bordin C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2499-2504. doi:10.1111/jdv.16774

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:700. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018

- Zhao Q, Fang X, Pang Z, et al. COVID‐19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2505-2510. doi:10.1111/jdv.16778

- Akasaka T, Kon S. Two cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising from erythema ab igne. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;99:735-742.

- Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1226-1228.

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Wollina U, Helm C, Hansel G, et al. Two cases of erythema ab igne, one with a squamous cell carcinoma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2007;142:415-418.

- Rudolph CM, Soyer HP, Wolf P, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in erythema ab igne. Hautarzt. 2000;51:260-263. doi:10.1007/s001050051115

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:147-148. doi:10.3109/14764172.2013.854623

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;62:77-78.

- Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, et al. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:432-435. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.123

Practice Points

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a skin condition caused by chronic exposure to heat; removal of the heat source often will result in self-resolution of the rash.

- Erythema ab igne can be a sign of underlying illness in patients self-treating chronic pain with application of heat.

- Recognition and discontinuation of the exposure with close observation are key components in the treatment of EAI.

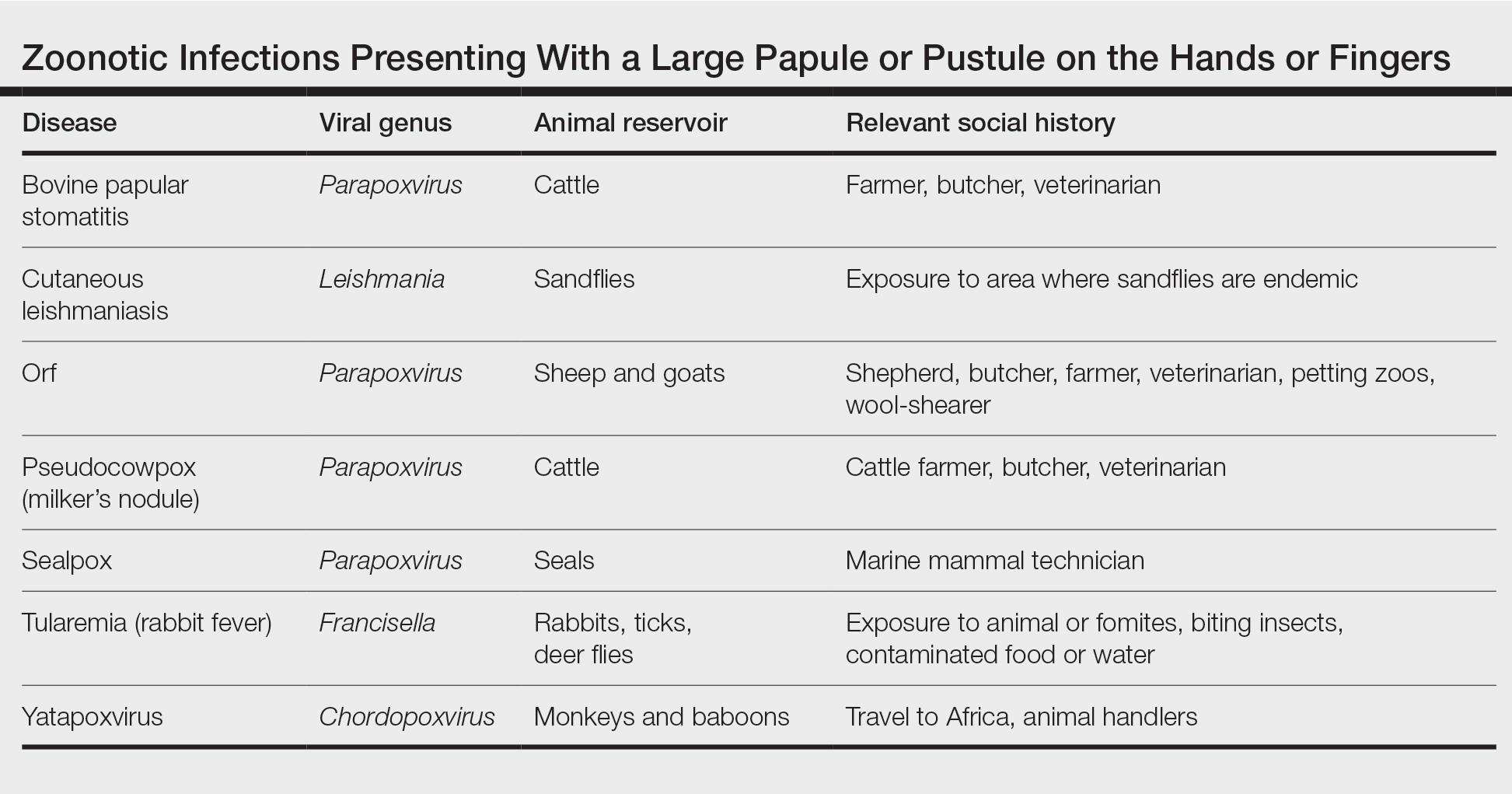

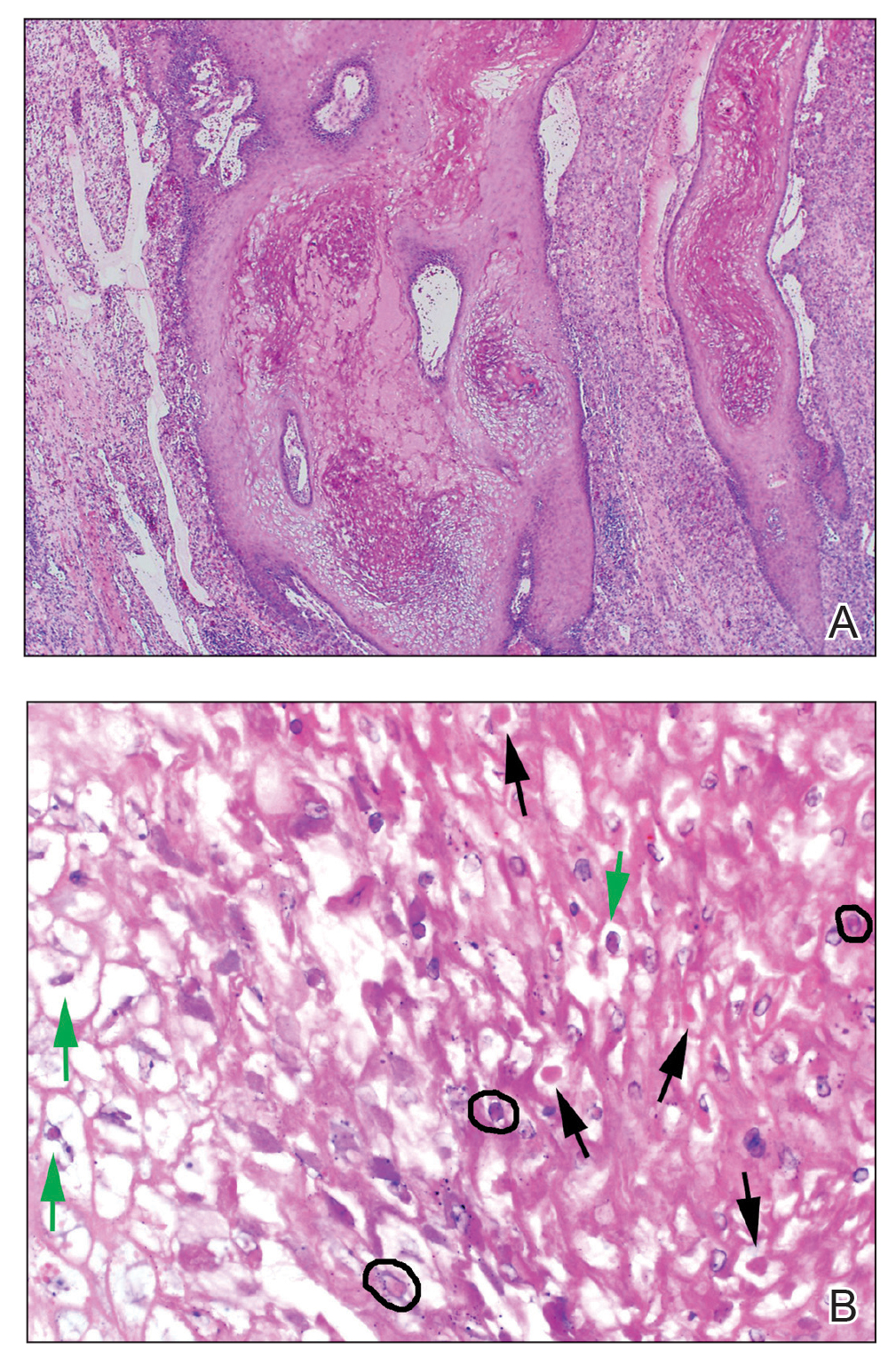

Orf Virus in Humans: Case Series and Clinical Review

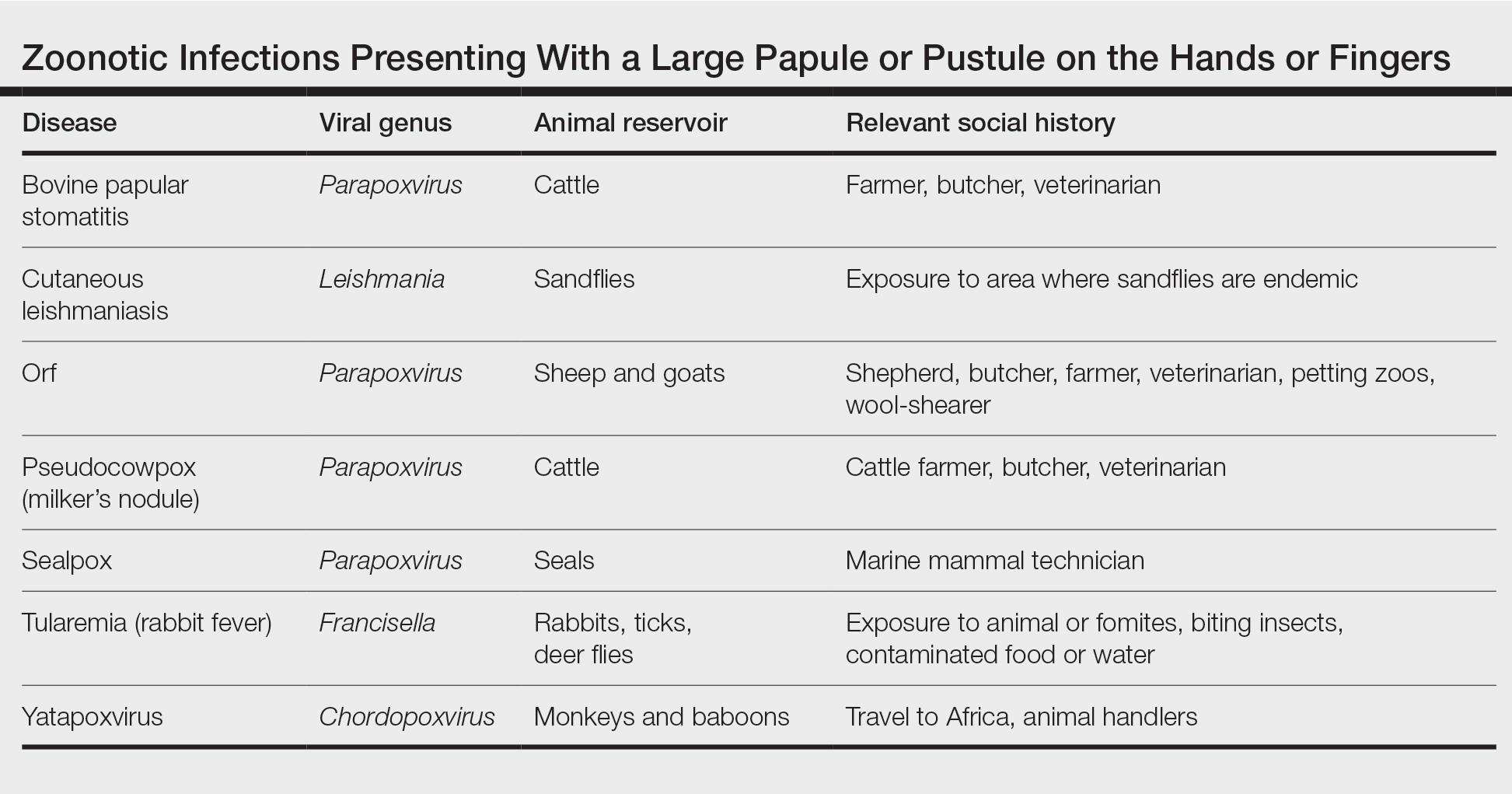

A patient presenting with a hand pustule is a phenomenon encountered worldwide requiring careful history-taking. Some occupations, activities, and various religious practices (eg, Eid al-Adha, Passover, Easter) have been implicated worldwide in orf infection. In the United States, orf virus usually is spread from infected animal hosts to humans. Herein, we review the differential for a single hand pustule, which includes both infectious and noninfectious causes. Recognizing orf virus as the etiology of a cutaneous hand pustule in patients is important, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing and/or treatments with suboptimal clinical outcomes.

Case Series

When conducting a search for orf virus cases at our institution (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa), 5 patient cases were identified.

Patient 1—A 27-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented to clinic with a tender red bump on the right ring finger that had been slowly growing over the course of 2 weeks and had recently started to bleed. A social history revealed that she owned several goats, which she frequently milked; 1 of the goats had a cyst on the mouth, which she popped approximately 1 to 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion on the finger. She also endorsed that she owned several cattle and various other animals with which she had frequent contact. A biopsy was obtained with features consistent with orf virus.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old man presented to clinic with a lesion of concern on the left index finger. Several days prior to presentation, the patient had visited the emergency department for swelling and erythema of the same finger after cutting himself with a knife while preparing sheep meat. Radiographs were normal, and the patient was referred to dermatology. In clinic, there was a 0.5-cm fluctuant mass on the distal interphalangeal joint of the third finger. The patient declined a biopsy, and the lesion healed over 4 to 6 weeks without complication.

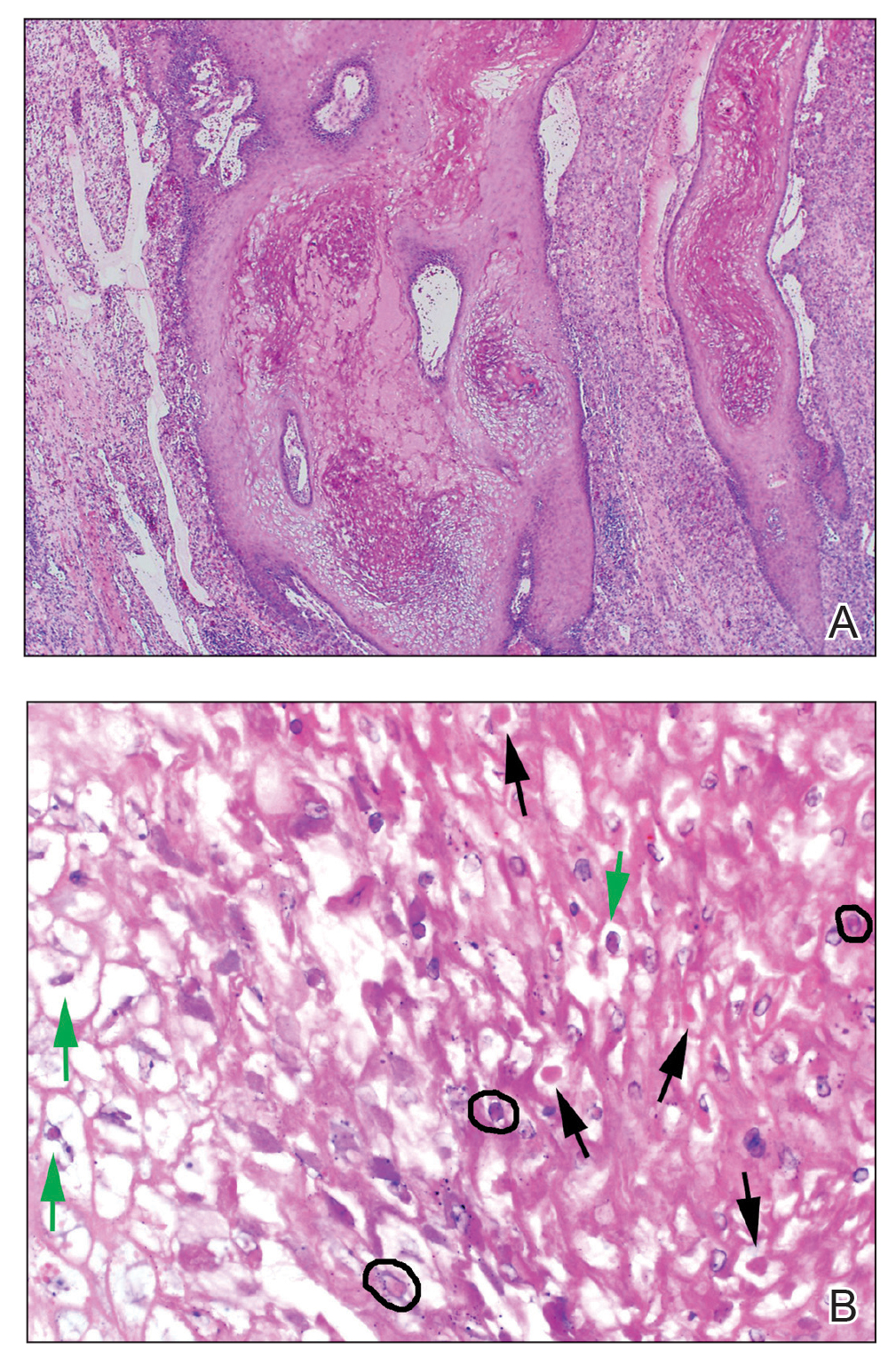

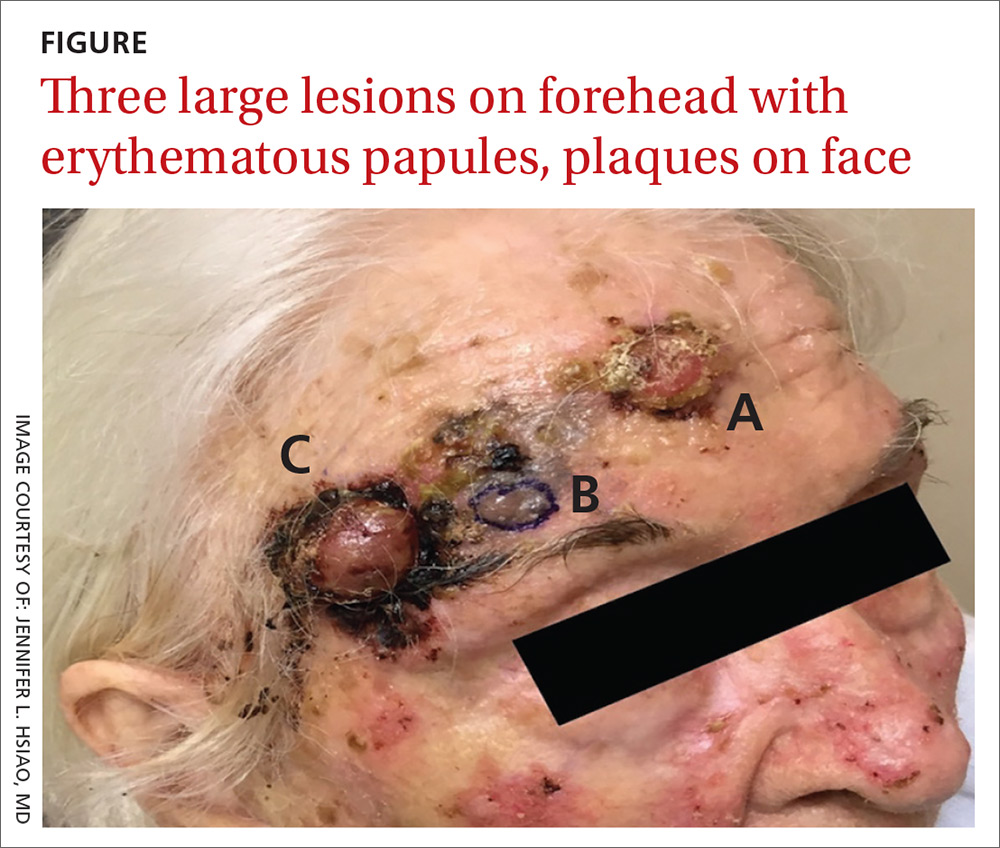

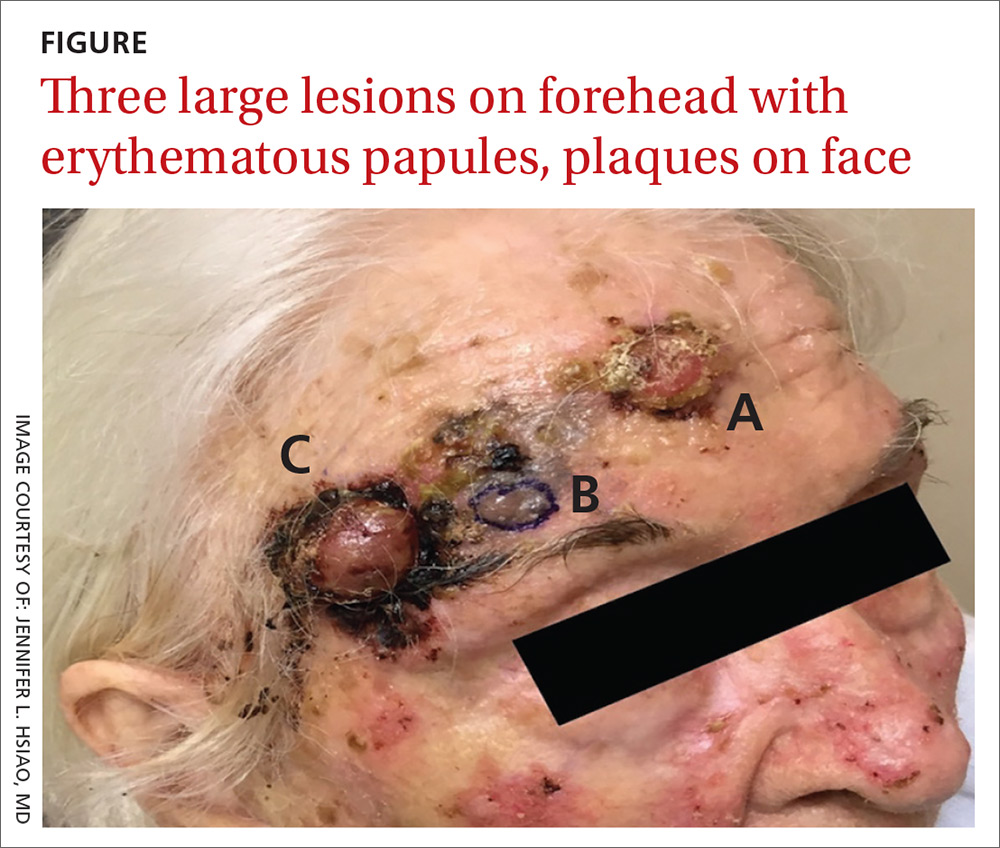

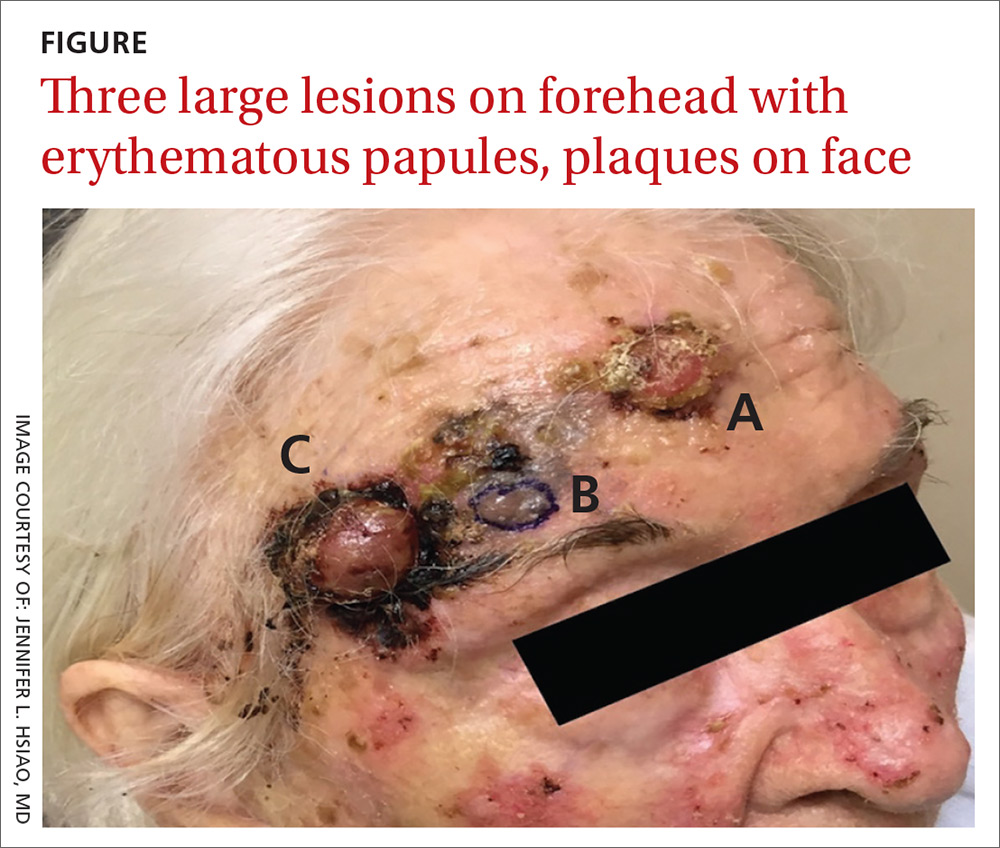

Patient 3—A 38-year-old man presented to clinic with 2 painless, large, round nodules on the right proximal index finger, with open friable centers noted on physical examination (Figure 1). The patient reported cutting the finger while preparing sheep meat several days prior. The nodules had been present for a few weeks and continued to grow. A punch biopsy revealed evidence of parapoxvirus infection consistent with a diagnosis of orf.

Patient 4—A 48-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a bleeding lesion on the left middle finger. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, friable, ulcerated nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left middle finger (Figure 2). Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned that he handled raw lamb meat after cutting the finger. A punch biopsy was obtained and was consistent with orf virus infection.

Patient 5—A 43-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chronic wound on the mid lower back that was noted to drain and crust over. She thought the lesion was improving, but it had become painful over the last few weeks. A shave biopsy of the lesion was consistent with orf virus. At follow-up, the patient was unable to identify any recent contact with animals.

Comment

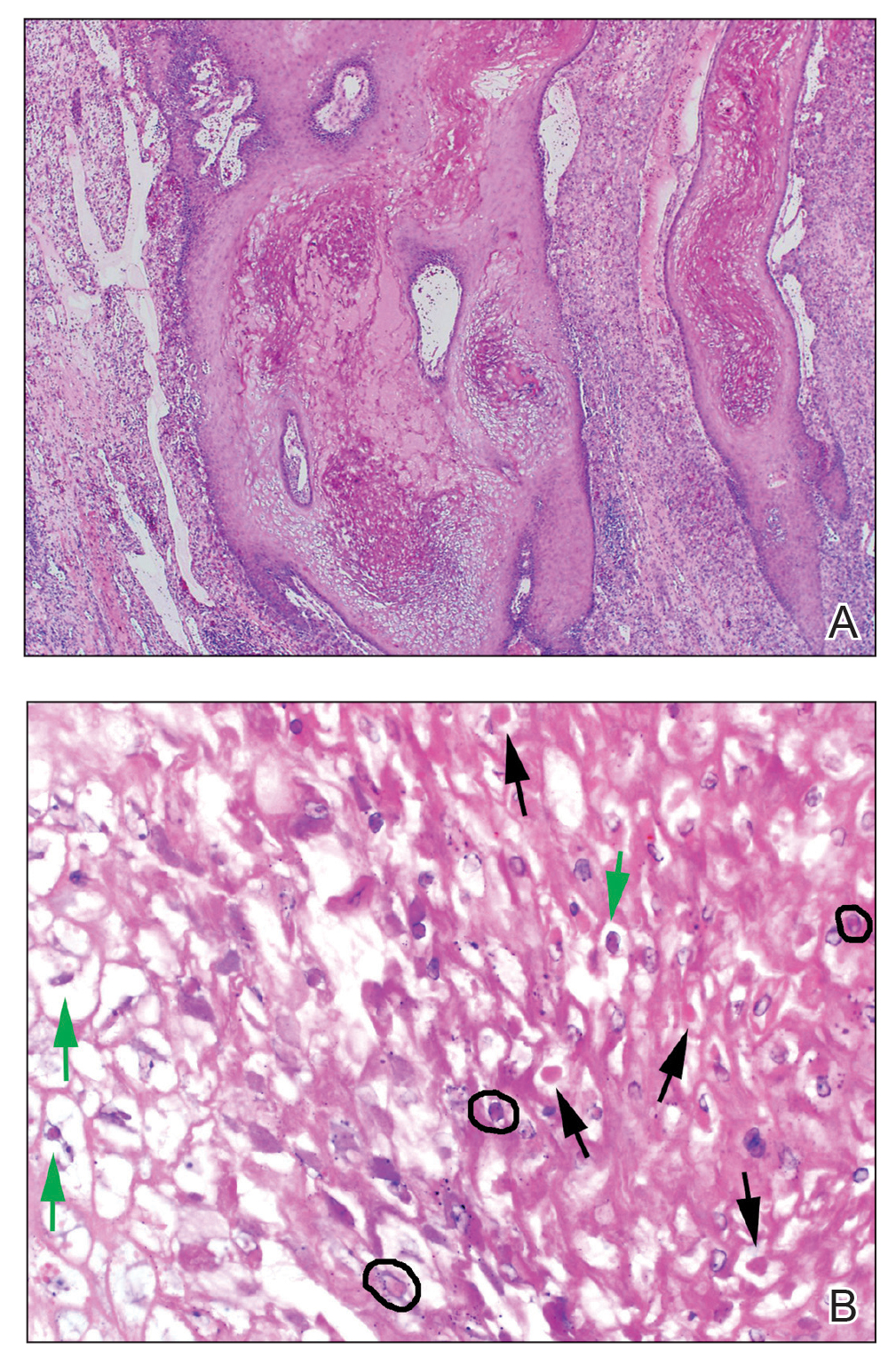

Transmission From Animals to Humans—Orf virus is a member of the Parapoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family.1 This virus is highly contagious among animals and has been described around the globe. The resulting disease also is known as contagious pustular dermatitis,2 soremuzzle,3 ecthyma contagiosum of sheep,4 and scabby mouth.5 This virus most commonly infects young lambs and manifests as raw to crusty papules, pustules, or vesicles around the mouth and nose of the animal.4 Additional signs include excessive salivation and weight loss or starvation from the inability to suckle because of the lesions.5 Although ecthyma contagiosum infection of sheep and goats has been well known for centuries, human infection was first reported in the literature in 1934.6

Transmission of orf to humans can occur when direct contact with an infected animal exhibiting active lesions occurs.7 Orf virus also can be transmitted through fomites (eg, from knives, wool, buildings, equipment) that previously were in contact with infected animals, making it relevant to ask all farmers about any animals with pustules around the mouth, nose, udders, or other commonly affected areas. Although sanitation efforts are important for prevention, orf virus is hardy, and fomites can remain on surfaces for many months.8 Transmission among animals and from animals to humans frequently occurs; however, human-to-human transmission is less common.9 Ecthyma contagiosum is considered an occupational hazard, with the disease being most prevalent in shepherds, veterinarians, and butchers.1,8 Disease prevalence in these occupations has been reported to be as high as 50%.10 Infections also are seen in patients who attend petting zoos or who slaughter goats and sheep for cultural practices.8

Clinical Characteristics in Humans—The clinical diagnosis of orf is dependent on taking a thorough patient history that includes social, occupational, and religious activities. Development of a nodule or papule on a patient’s hand with recent exposure to fomites or direct contact with a goat or sheep up to 1 week prior is extremely suggestive of an orf virus infection.

Clinically, orf most often begins as an individual papule or nodule on the dorsal surface of the patient’s finger or hand and ranges from completely asymptomatic to pruritic or even painful.1,8 Depending on how the infection was inoculated, lesions can vary in size and number. Other sites that have been reported less frequently include the genitals, legs, axillae, and head.11,12 Lesions are roughly 1 cm in diameter but can vary in size. Ecthyma contagiosum is not a static disease but changes in appearance over the course of infection. Typically, lesions will appear 3 to 7 days after inoculation with the orf virus and will self-resolve 6 to 8 weeks later.

Orf lesions have been described to progress through 6 distinct phases before resolving: maculopapular (erythematous macule or papule forms), targetoid (formation of a necrotic center with red outer halo), acute (lesion begins to weep), regenerative (lesion becomes dry), papilloma (dry crust becomes papillomatous), and regression (skin returns to normal appearance).1,8,9 Each phase of ecthyma contagiosum is unique and will last up to 1 week before progressing. Because of this prolonged clinical course, patients can present at any stage.

Reports of systemic symptoms are uncommon but can include lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise.13 Although the disease course in immunocompetent individuals is quite mild, immunocompromised patients may experience persistent orf lesions that are painful and can be much larger, with reports of several centimeters in diameter.14