User login

Histiocytoid Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Challenging Case With Features of Sweet Syndrome

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

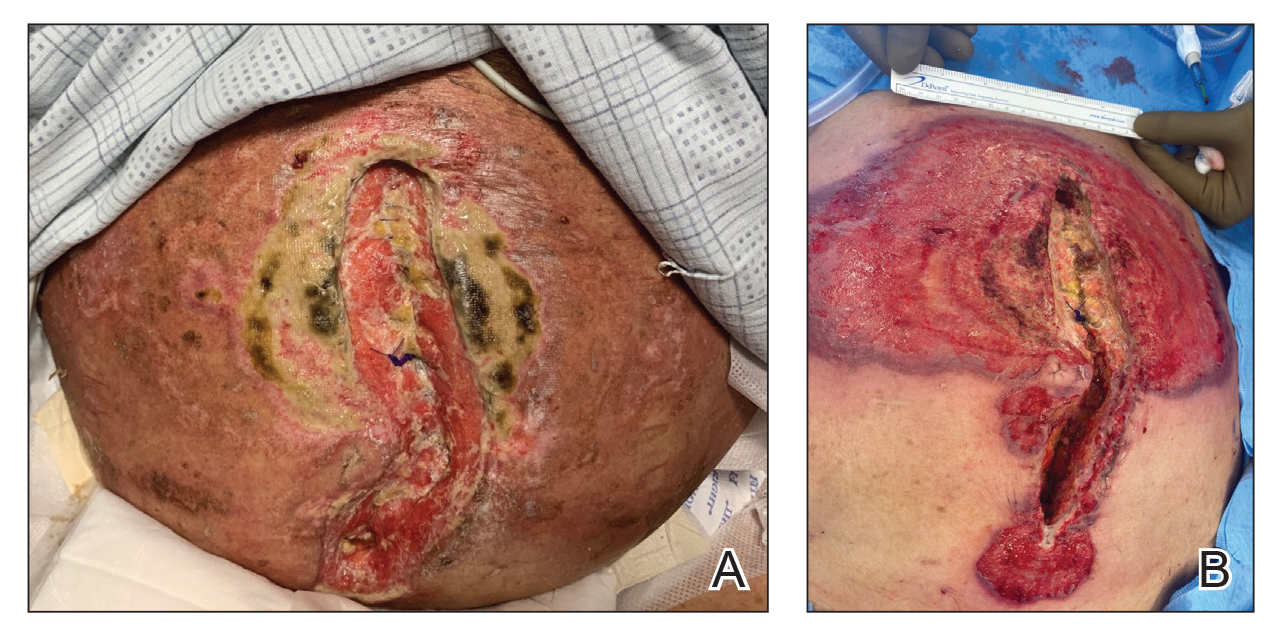

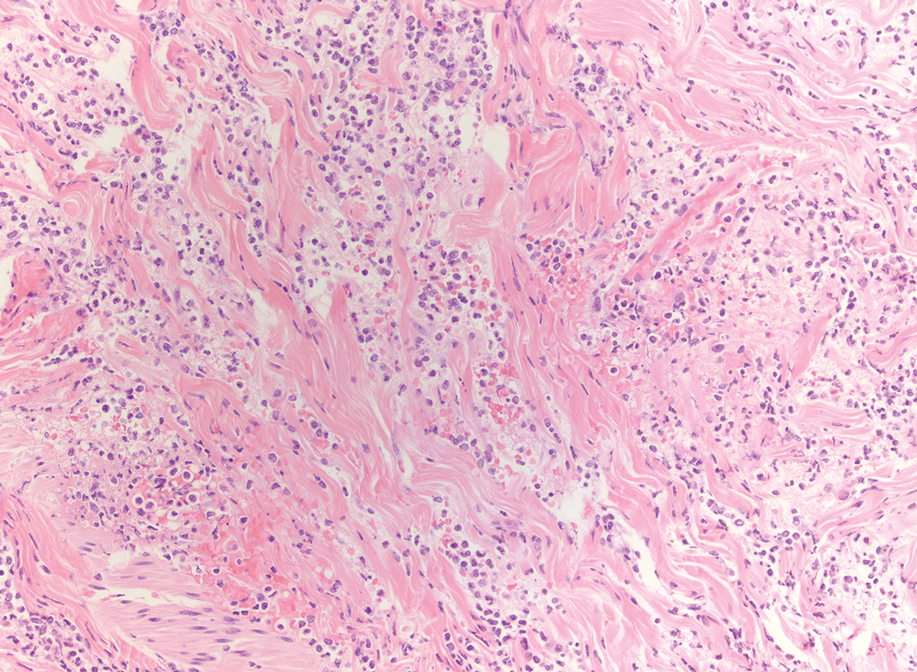

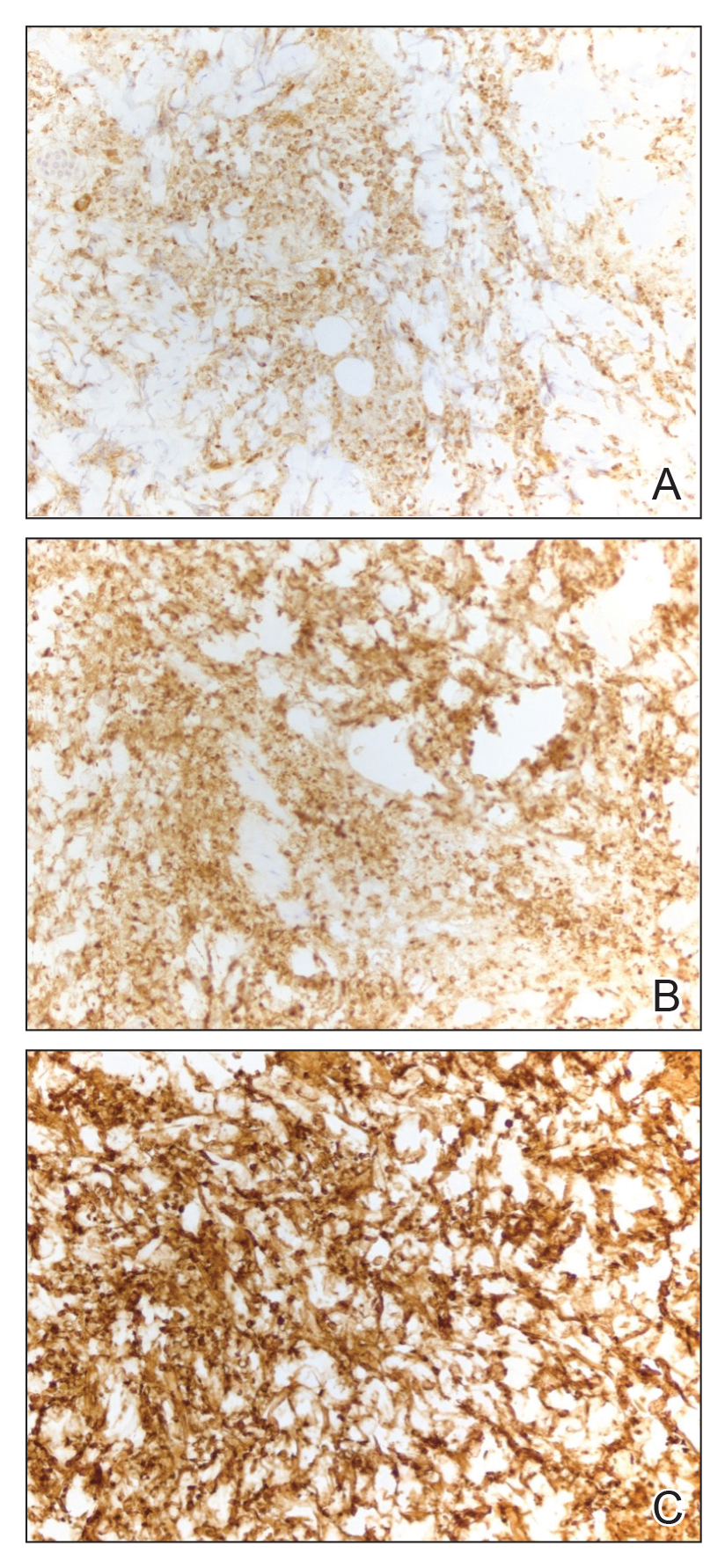

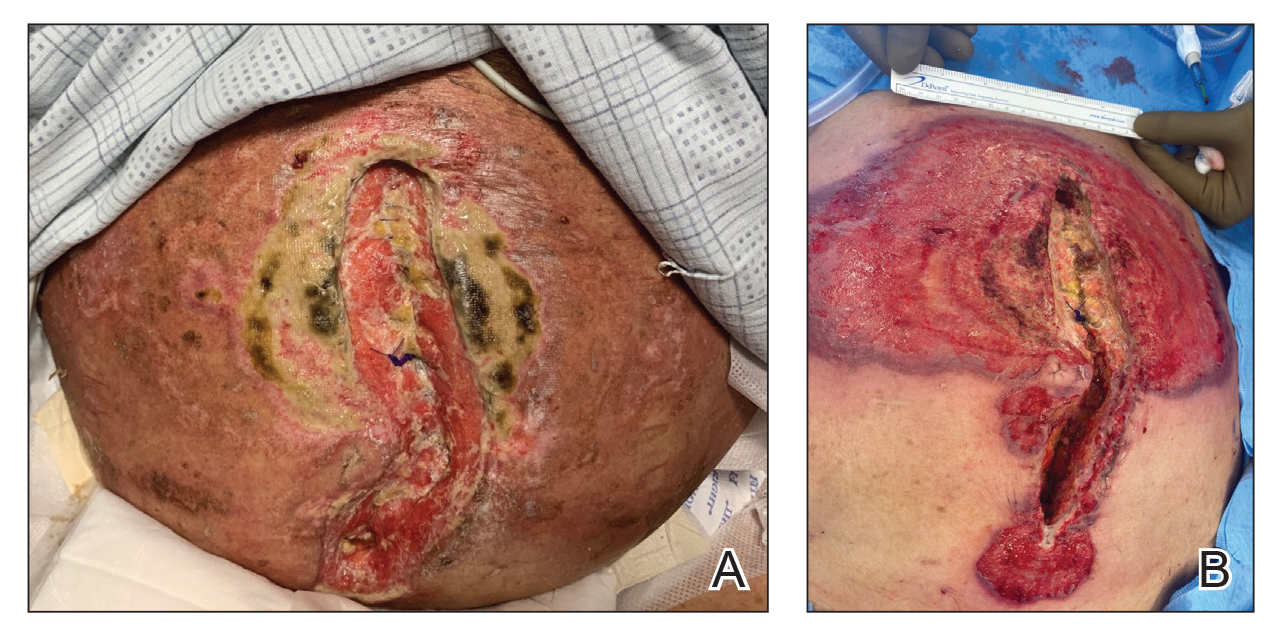

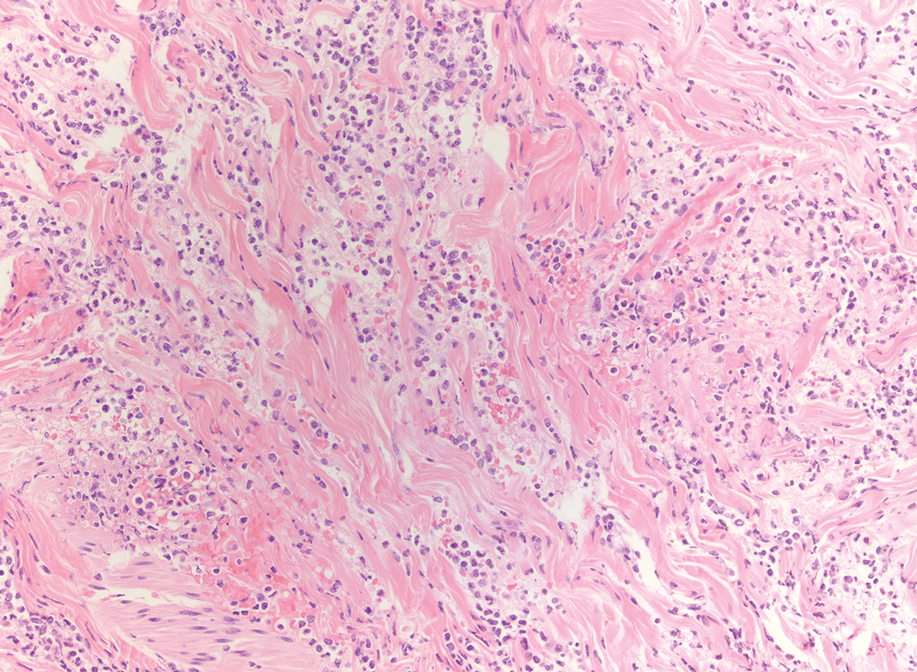

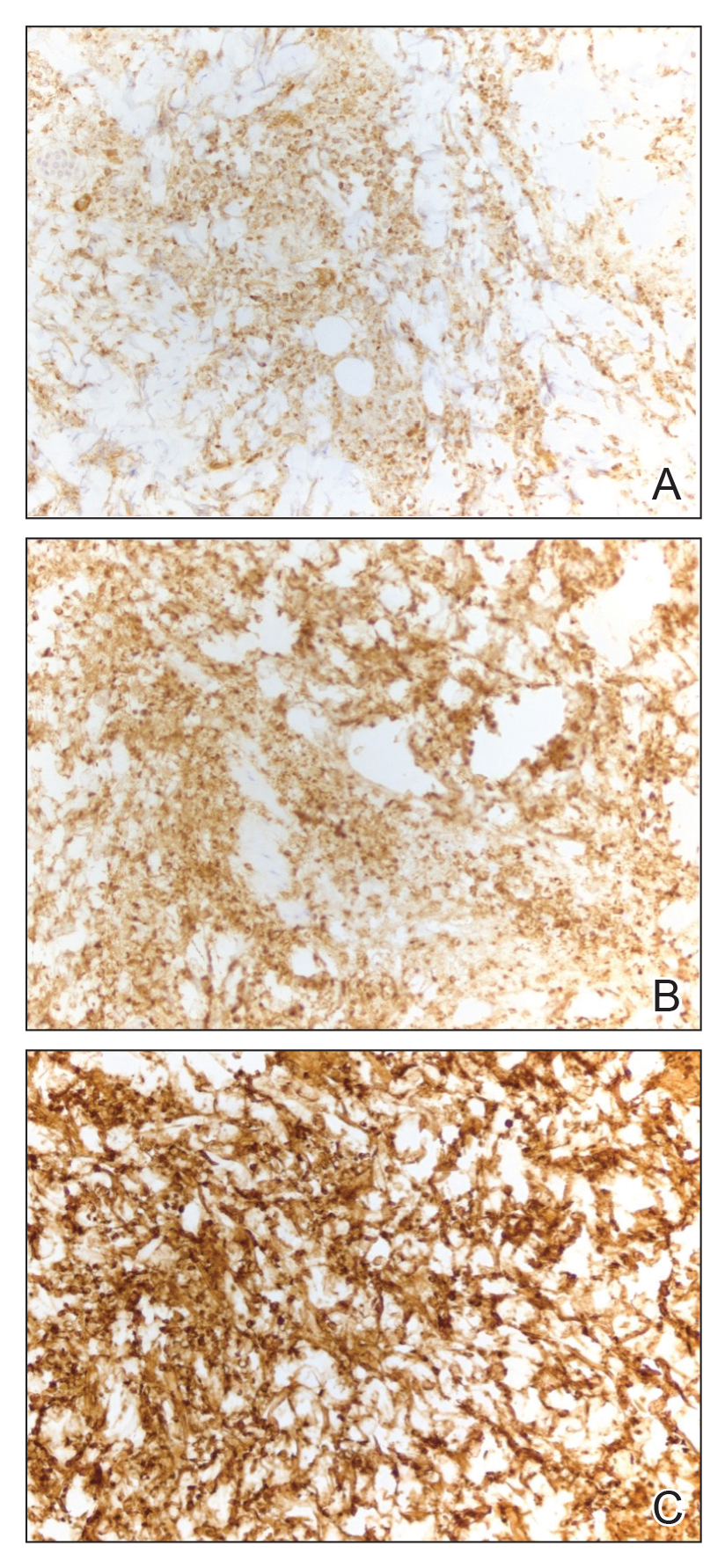

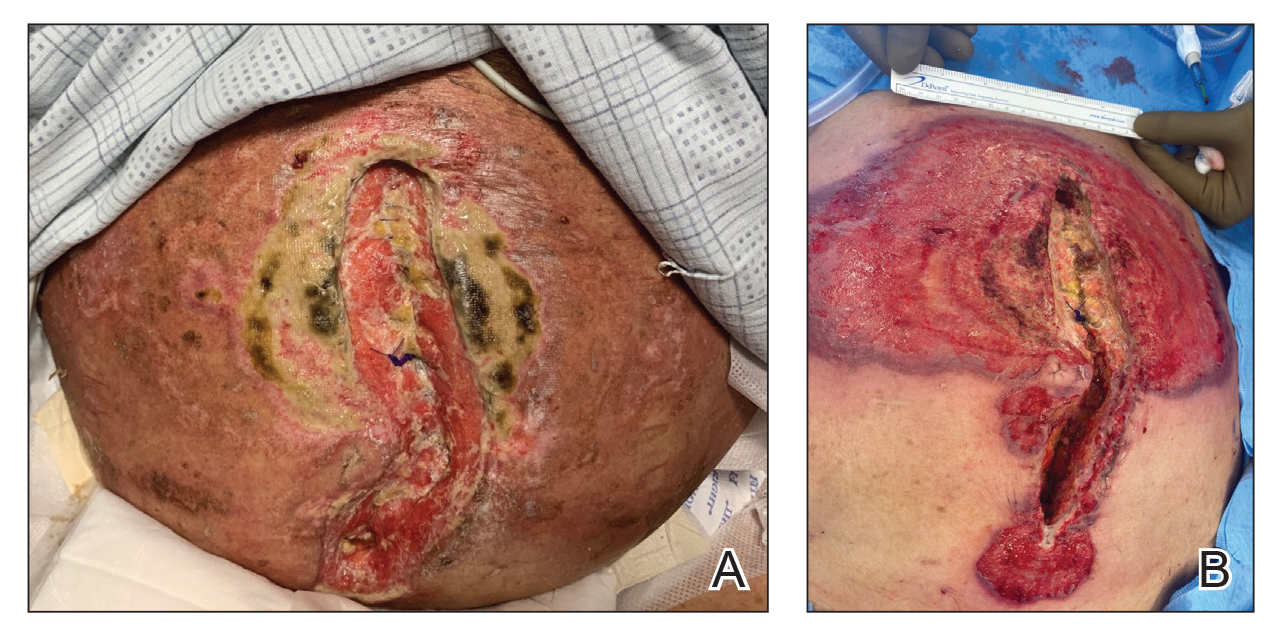

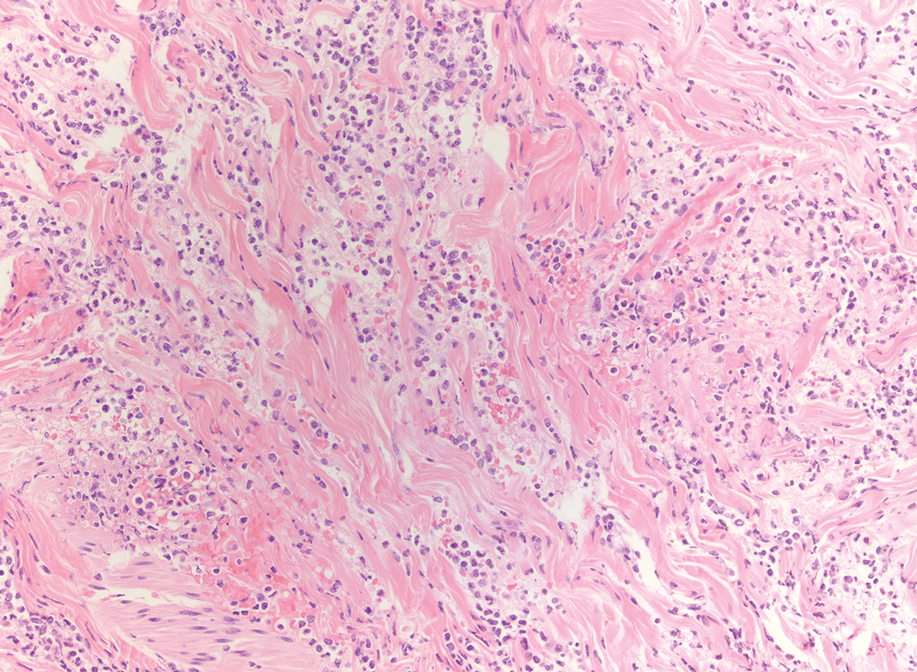

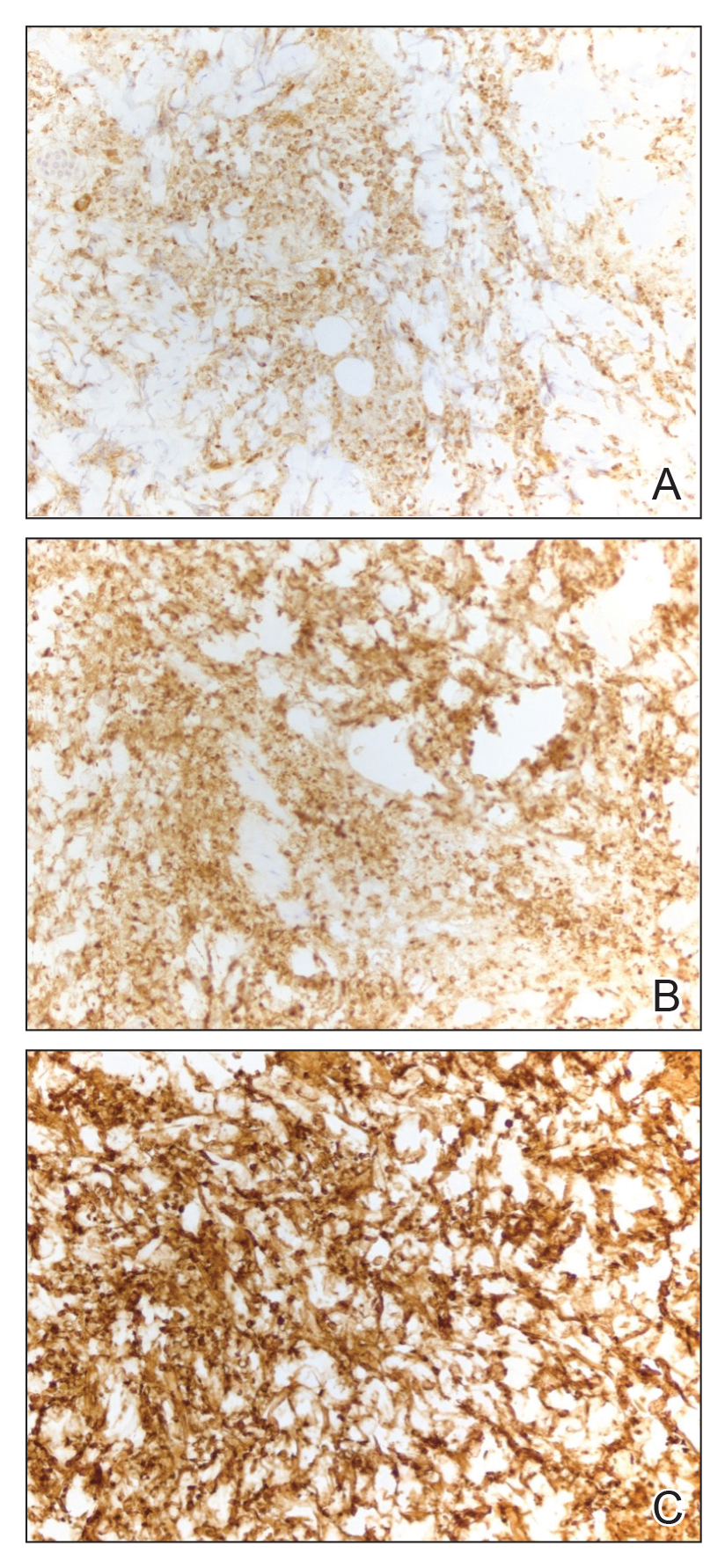

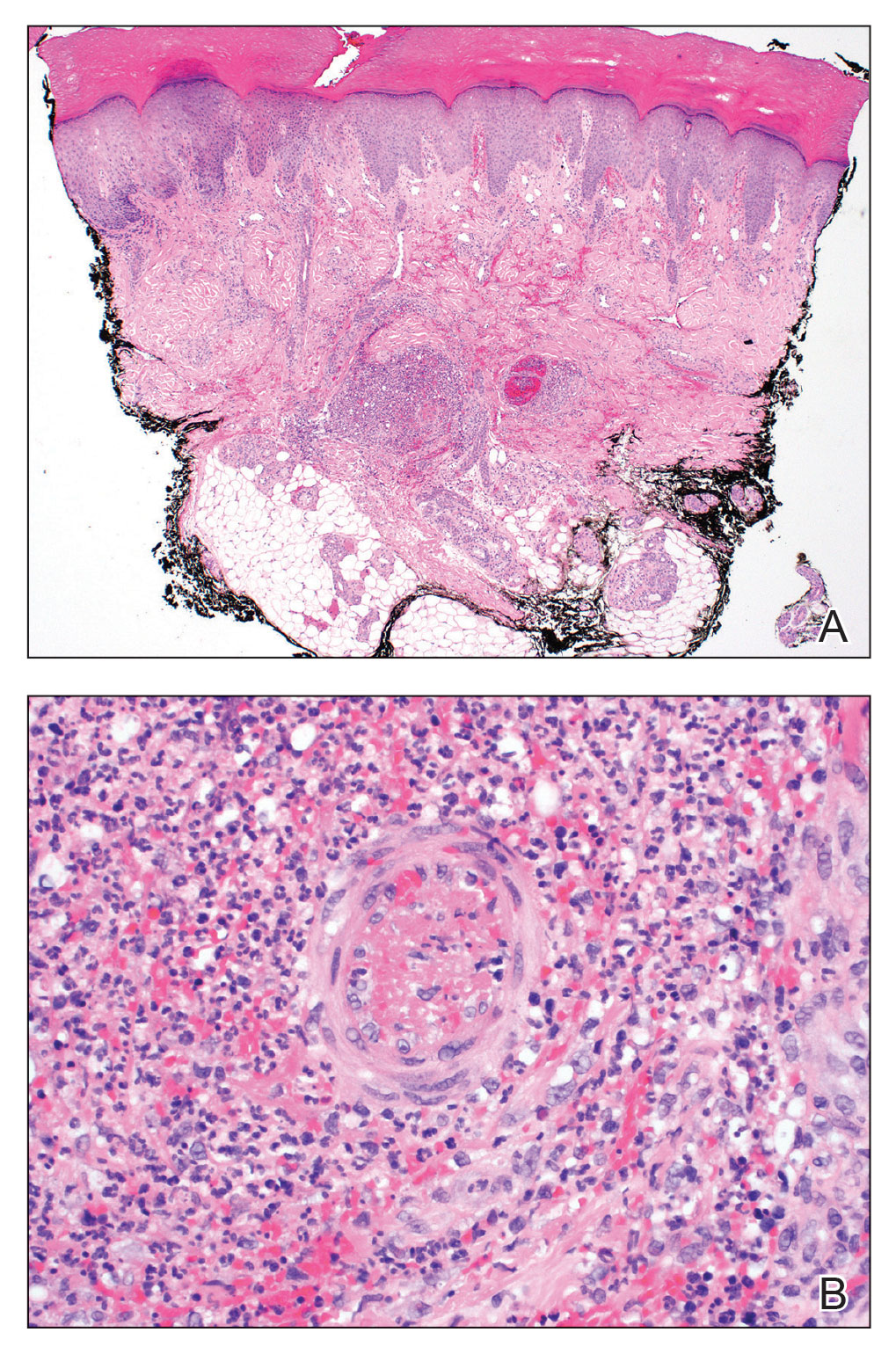

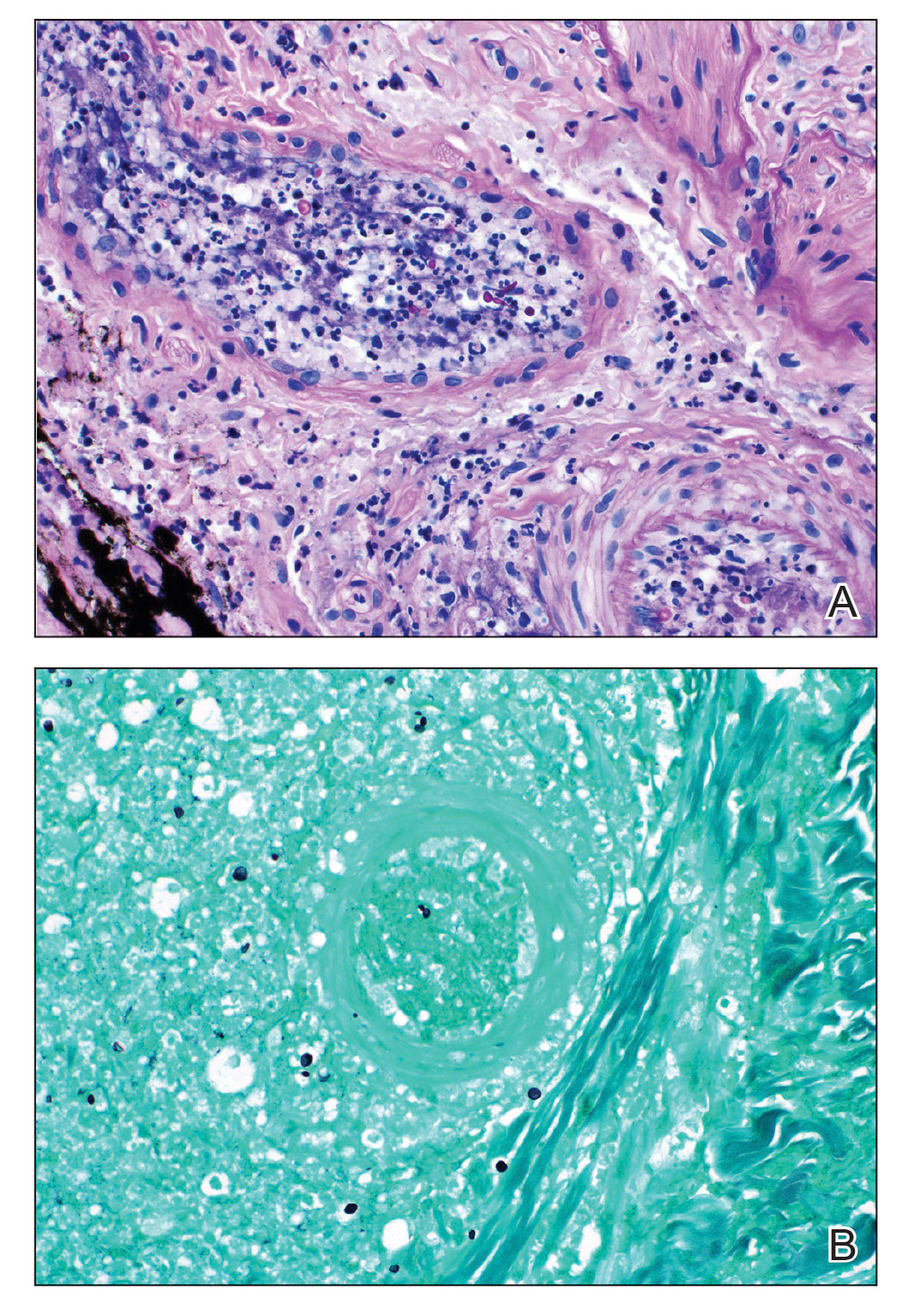

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

Practice Points:

- Dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be aware of the histiocytoid variant of pyoderma gangrenosum, which can clinical and histologic features that overlap with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome.

- When considering a diagnosis of histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatoses, leukemia cutis or aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma should be ruled out.

- Similar to histiocytoid Sweet syndrome and neutrophilic dermatoses in the setting of hematologic or solid organ malignancy, histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum may respond well to high-dose systemic corticosteroids.

Fungal Osler Nodes Indicate Candidal Infective Endocarditis

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

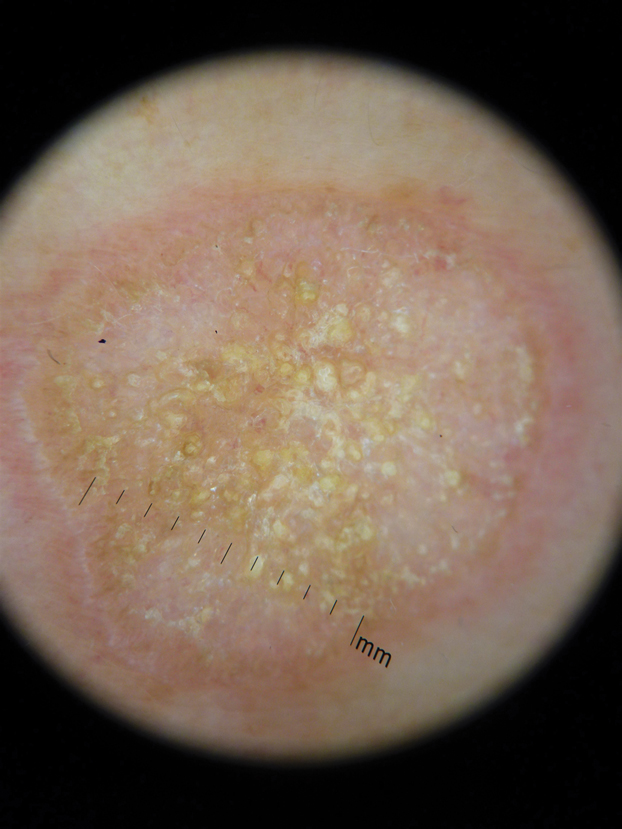

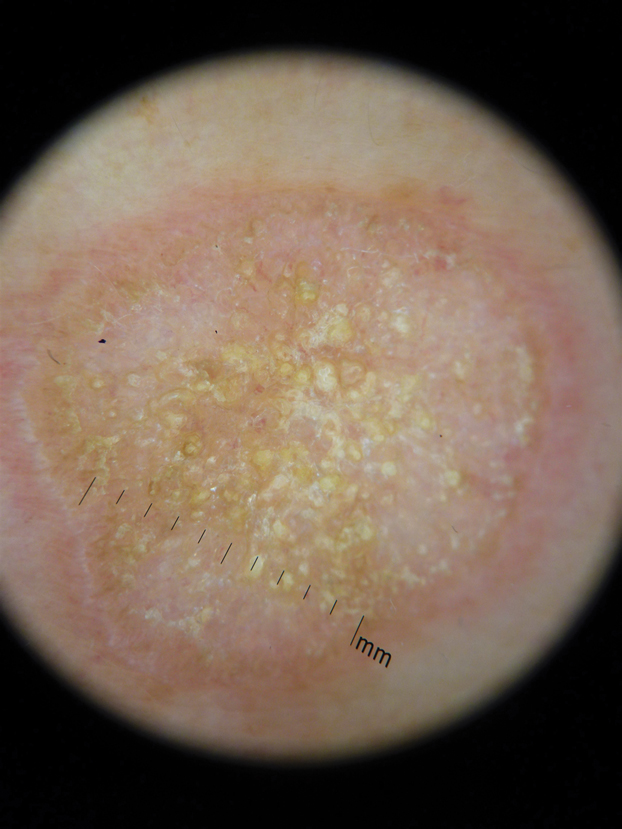

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

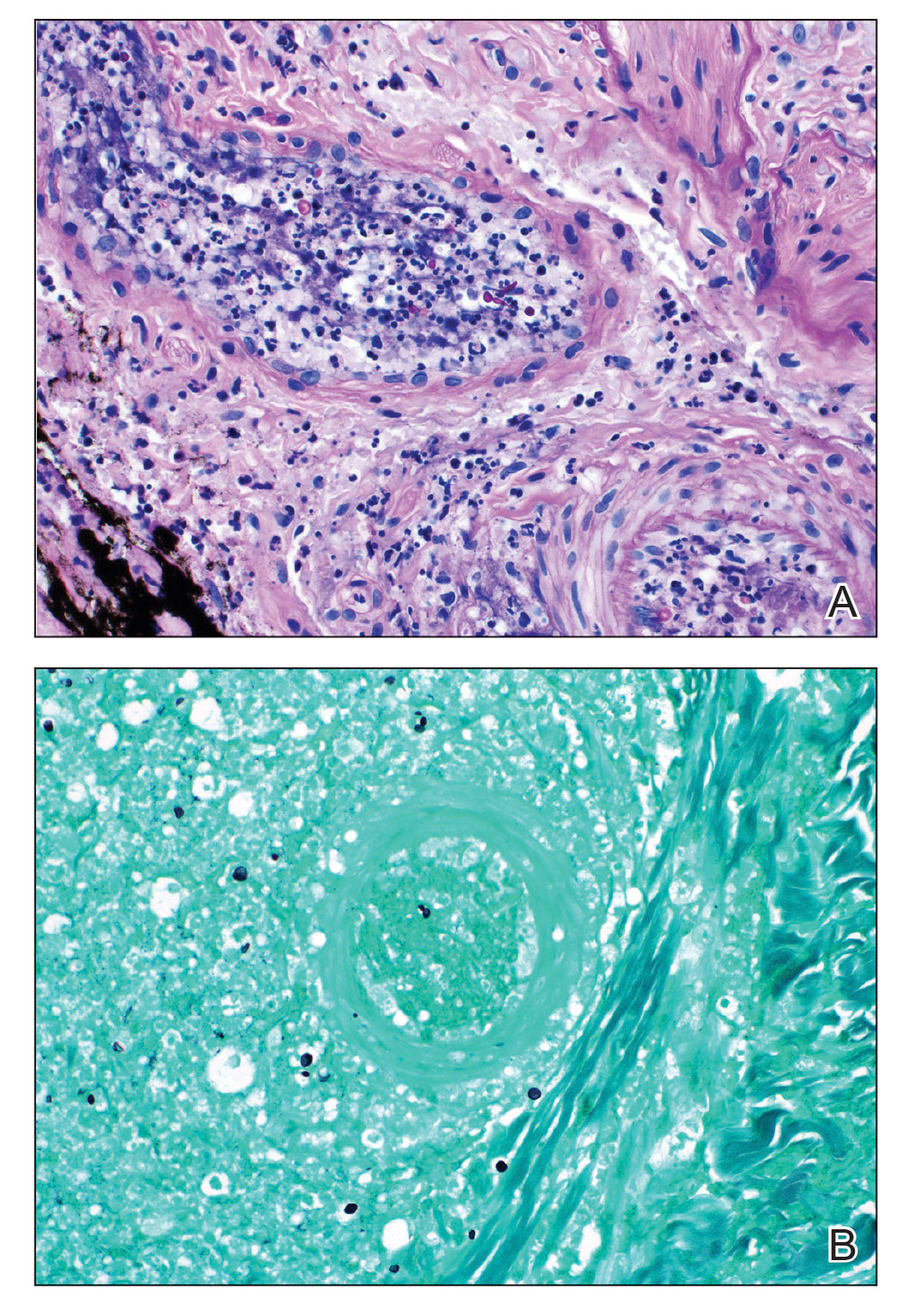

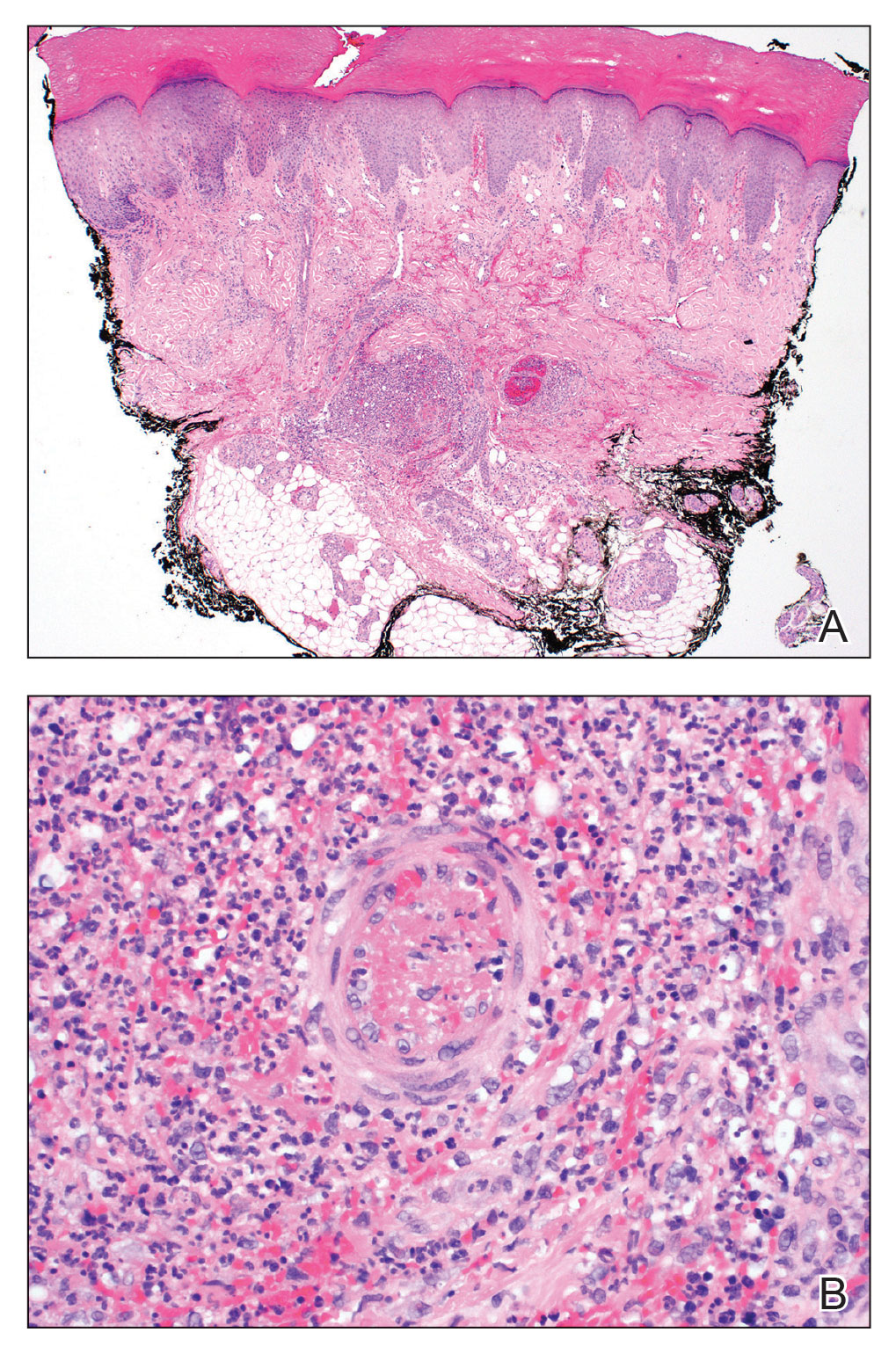

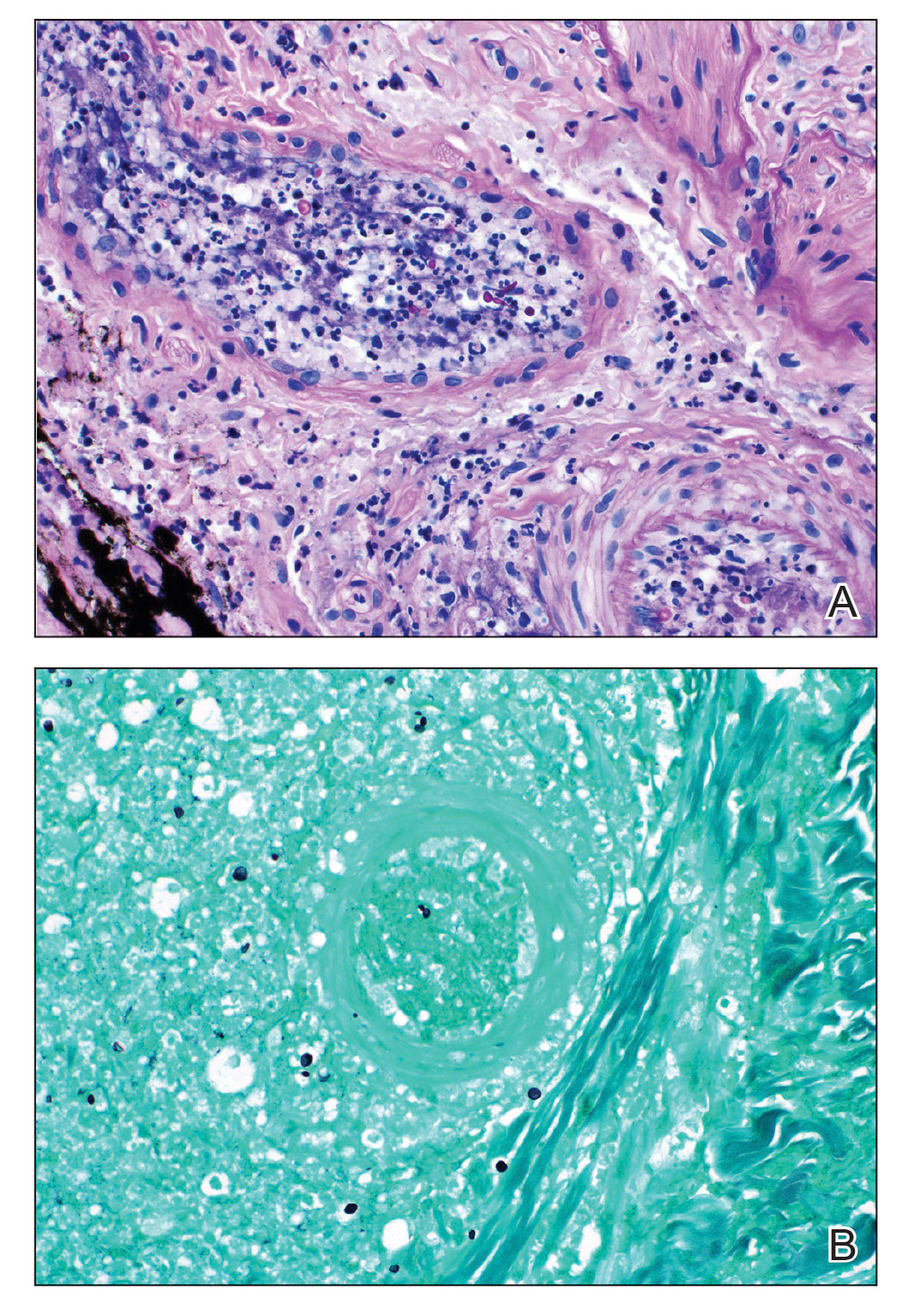

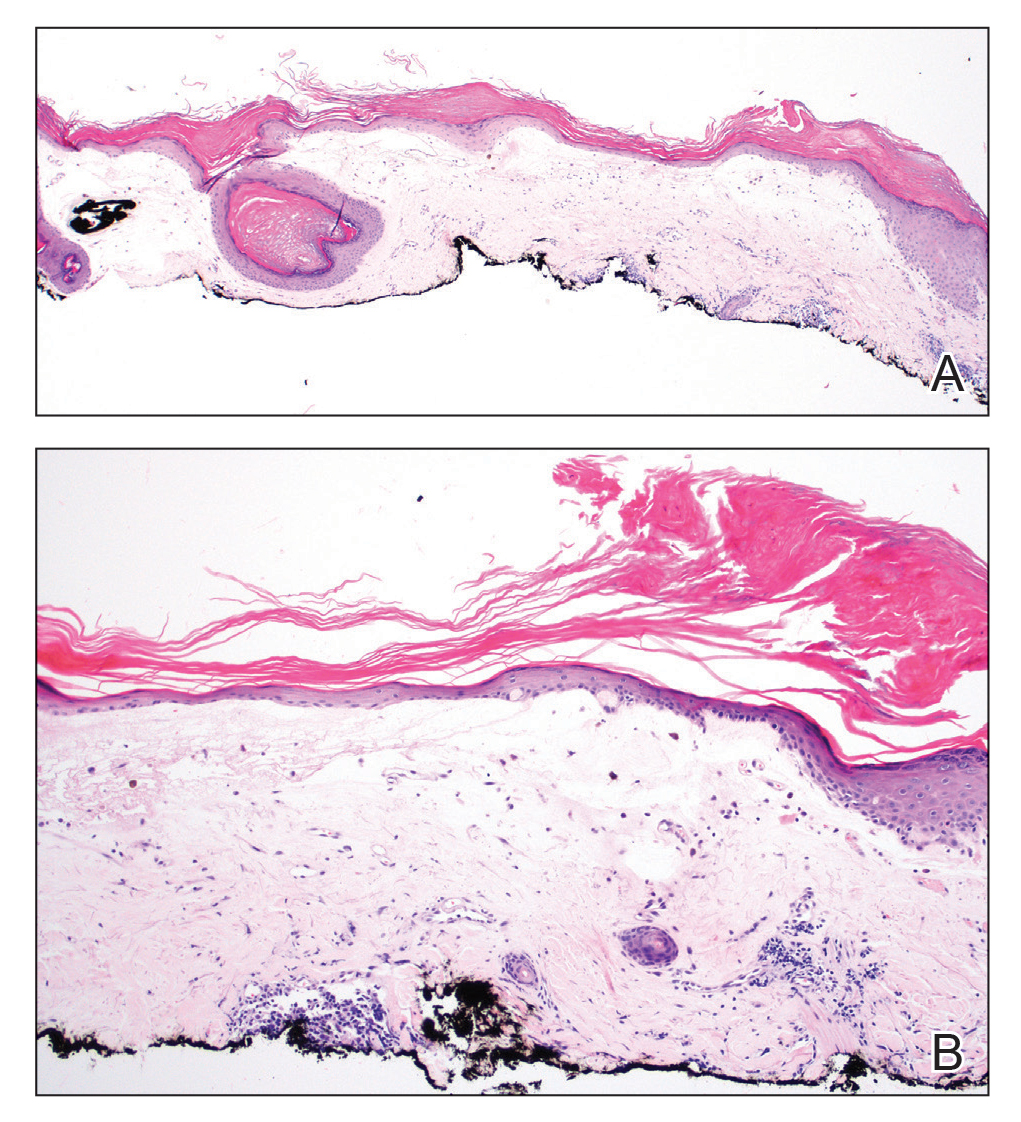

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

PRACTICE POINTS

- Fungal infective endocarditis is rare, and diagnostic tests such as blood cultures and echocardiography may not detect the disease.

- The mortality rate of fungal endocarditis is high, with improved clinical outcomes if diagnosed and treated early.

- Clinicopathologic correlation between integumentary examination and skin biopsy findings may provide timely diagnosis, thereby guiding appropriate therapy.

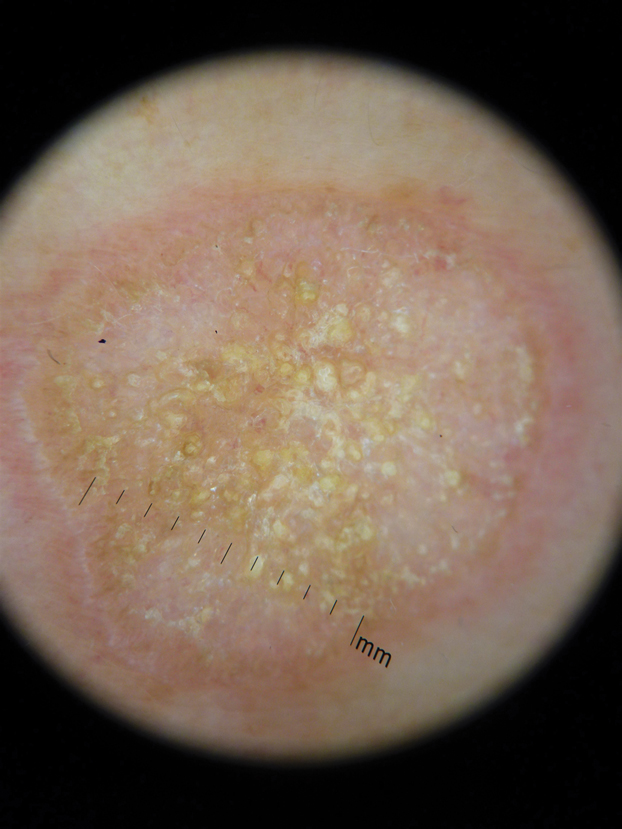

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

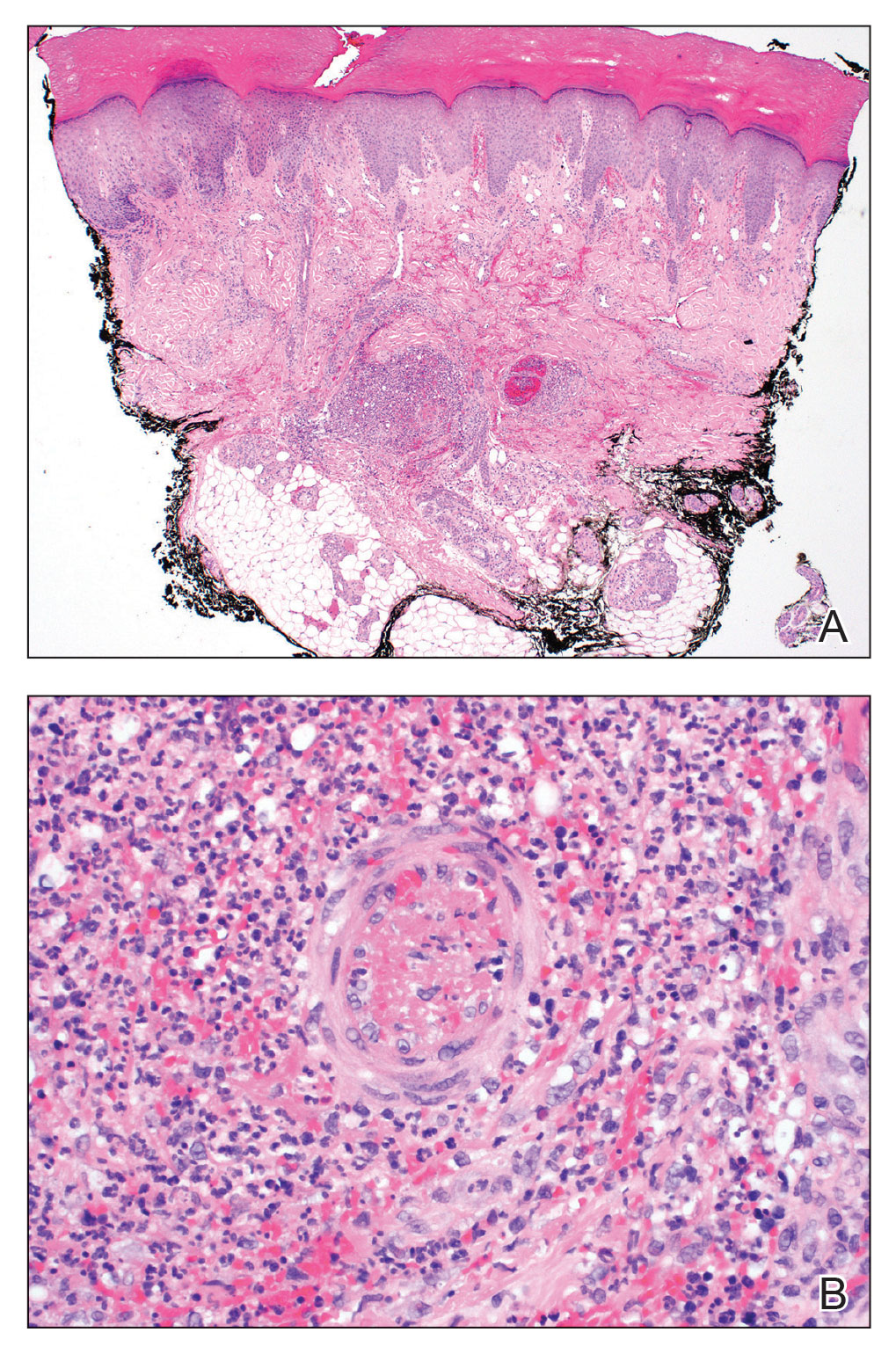

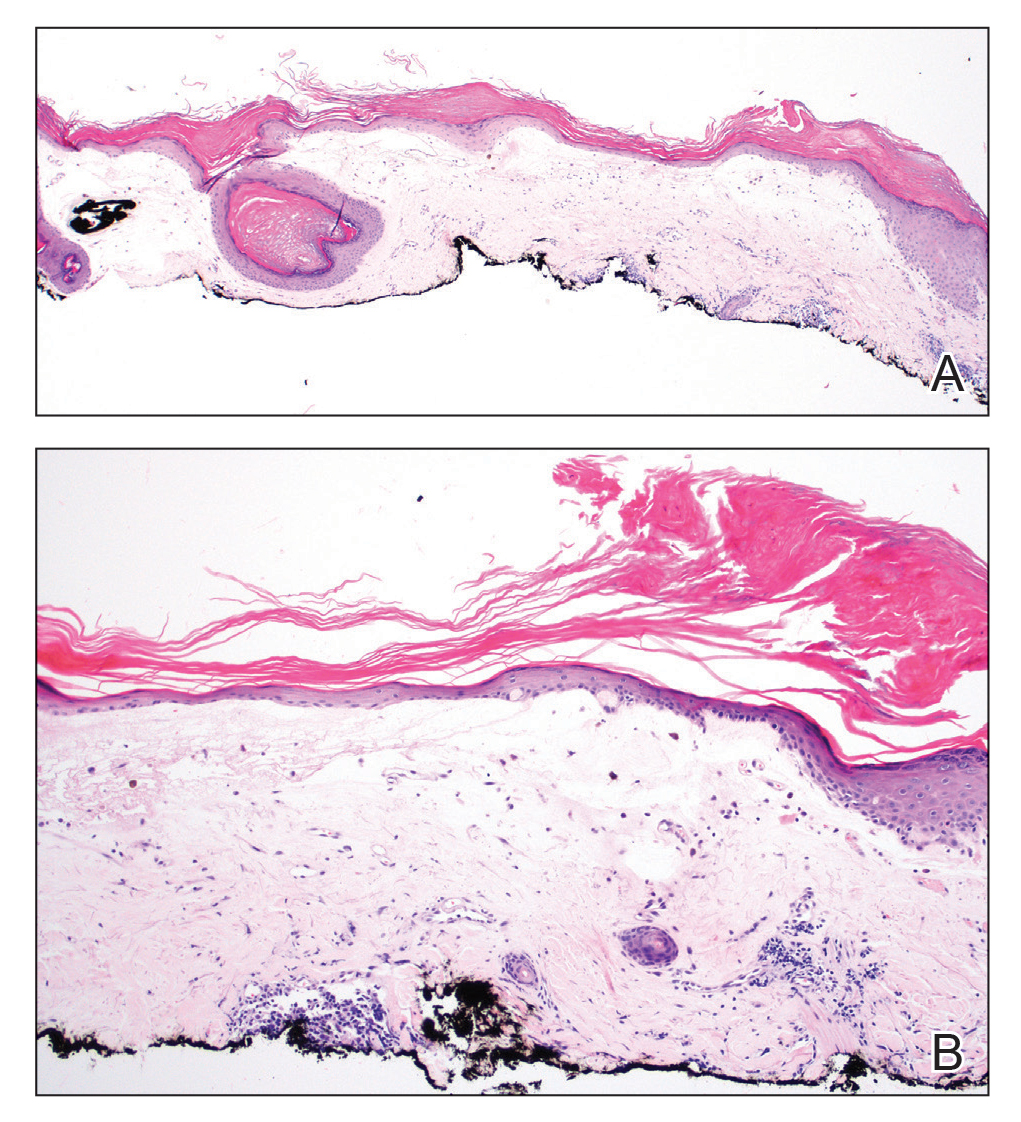

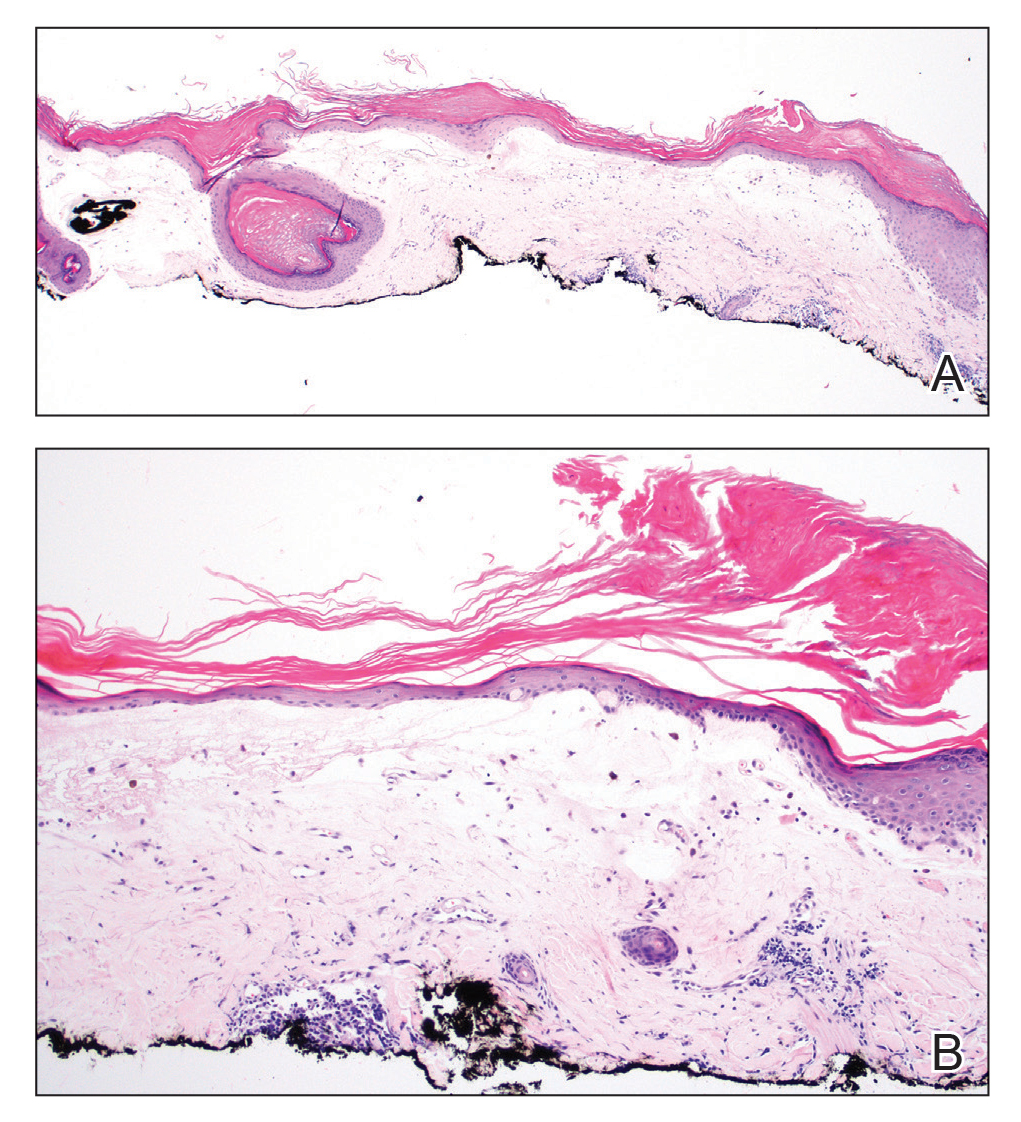

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2