User login

Botanical Briefs: Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

An ancient tree of the Ginkgoaceae family, Ginkgo biloba is known as a living fossil because its genome has been identified in fossils older than 200 million years.1 An individual tree can live longer than 1000 years. Originating in China, G biloba (here, “ginkgo”) is cultivated worldwide for its attractive foliage (Figure 1). Ginkgo extract has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine; however, contact with the plant proper can provoke allergic contact dermatitis.

Dermatitis-Inducing Components

The allergenic component of the ginkgo tree is ginkgolic acid, which is structurally similar to urushiol and anacardic acid.2,3 This compound can cause a cross-reaction in a person previously sensitized by contact with other plants. Urushiol is found in poison ivy(Toxicodendron radicans); anacardic acid is found in the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale). Both plants belong to the family Anacardiaceae, commonly known as the cashew family.

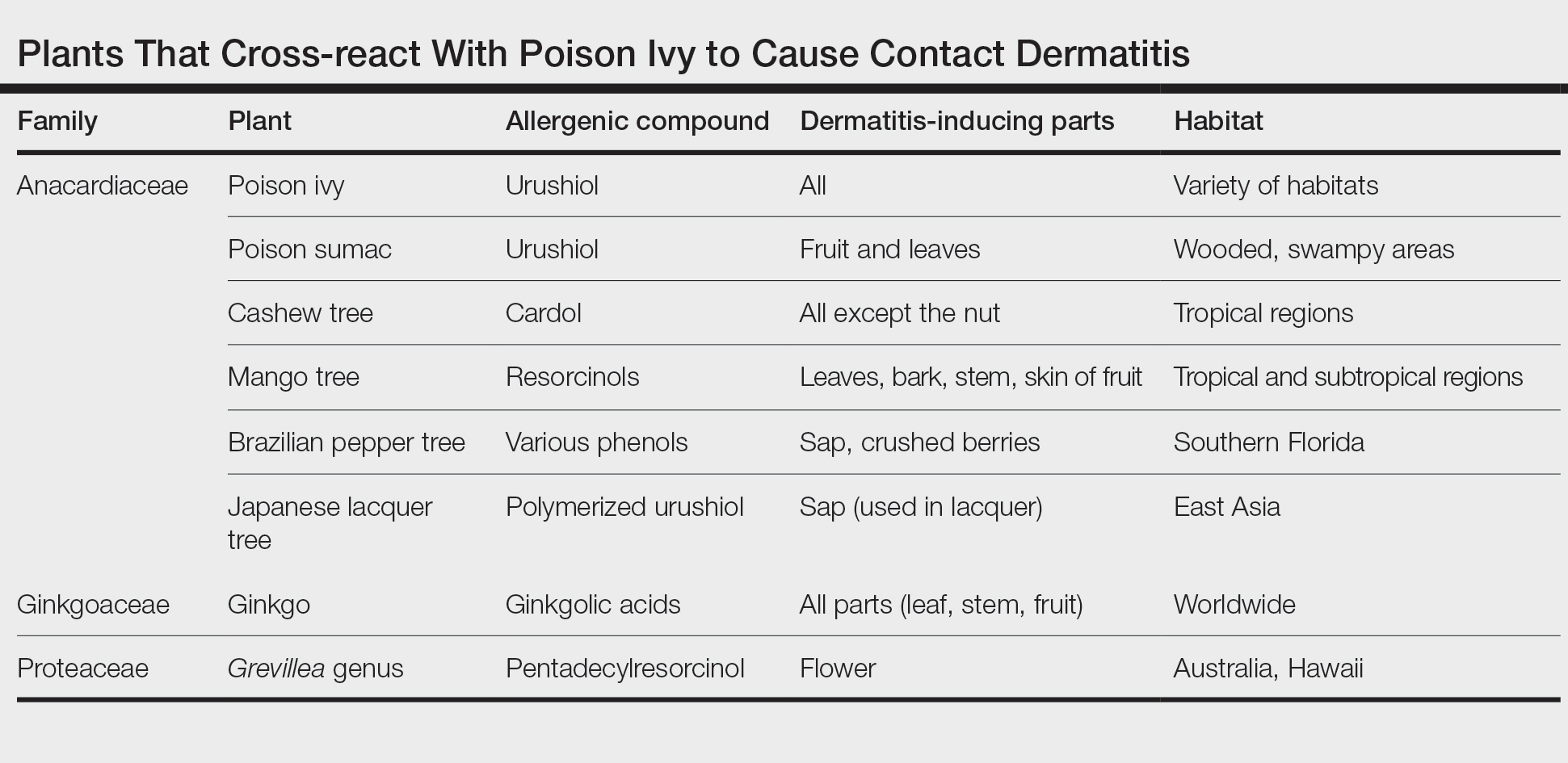

Members of Anacardiaceae are the most common causes of plant-induced allergic contact dermatitis and include the cashew tree, mango tree, poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. These plants can cross-react to cause contact dermatitis (Table).3 Patch tests have revealed that some individuals who are sensitive to components of the ginkgo tree also demonstrate sensitivity to poison ivy and poison sumac4,5; countering this finding, Lepoittevin and colleagues6 demonstrated in animal studies that there was no cross-reactivity between ginkgo and urushiol, suggesting that patients with a reported cross-reaction might truly have been previously sensitized to both plants. In general, patients who have a history of a reaction to any Anacardiaceae plant should take precautions when handling them.

Therapeutic Benefit of Ginkgo

Ginkgo extract is sold as the herbal supplement EGB761, which acts as an antioxidant.7 In France, Germany, and China, it is a commonly prescribed herbal medicine.8 It is purported to support memory and attention; studies have shown improvement in cognition and in involvement with activities of daily living for patients with dementia.9,10 Ginkgo extract might lessen peripheral vascular disease and cerebral circulatory disease, having been shown in vitro and in animal models to prevent platelet aggregation induced by platelet-activating factor and to stimulate vasodilation by increasing production of nitric oxide.11,12

Furthermore, purified ginkgo extract might have beneficial effects on skin. A study in rats showed that when intraperitoneal ginkgo extract was given prior to radiation therapy, 100% of rats receiving placebo developed radiation dermatitis vs 13% of those that received ginkgo extract (P<.0001). An excisional skin biopsy showed a decrease in markers of oxidative stress in rats that received ginkgo extract prior to radiation.7

A randomized, double-blind clinical trial showed a significant reduction in disease progression in vitiligo patients assigned to receive ginkgo extract orally compared to placebo (P=.006).13 Research for many possible uses of ginkgo extract is ongoing.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Contact with the fruit of the ginkgo tree can induce allergic contact dermatitis,14 most often as erythematous papules, vesicles, and in some cases edema.5,15

Exposures While Picking Berries—In 1939, Bolus15 reported the case of a patient who presented with edema, erythema, and vesicular lesions involving the hands and face after picking berries from a ginkgo tree. Later, patch testing on this patient, using ginkgo fruit, resulted in burning and stinging that necessitated removal of the patch, suggesting an irritant reaction. This was followed by a vesicular reaction that then developed within 24 hours, which was more consistent with allergy. Similarly, in 1988, a case series of contact dermatitis was reported in 3 patients after gathering ginkgo fruit.5

Incidental Exposure While Walking—In 1965, dermatitis broke out in 35 high school students, mainly affecting exposed portions of the leg, after ginkgo fruit fell and its pulp was exposed on a path at their school.4 Subsequently, patch testing was performed on 29 volunteers—some who had been exposed to ginkgo on that path, others without prior exposure. It was established that testing with ginkgo pulp directly caused an irritant reaction in all students, regardless of prior ginkgo exposure, but all prior ginkgo-exposed students in this study reacted positively to an acetone extract of ginkgo pulp and either poison ivy extract or pentadecylcatechol.4

Systemic Contact After Eating Fruit—An illustrative case of dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis was reported in a man with history of poison oak contact dermatitis who had eaten fruit from a ginkgo tree, suggesting systemic contact dermatitis. Weeks after resolution of symptoms, he reacted positively to ginkgo fruit and poison ivy extracts on patch testing.16

Ginkgo dermatitis tends to resolve upon removal of the inciting agent and application of a topical steroid.8,17 Although many reported cases involve the fruit, allergic contact dermatitis can result from exposure to any part of the plant. In a reported case, a woman developed airborne contact dermatitis from working with sarcotesta of the ginkgo plant.18 Despite wearing rubber gloves, she broke out 1 week after exposure with erythema on the face and arms and severe facial edema.

Ginkgo leaves also can cause allergic contact dermatitis.19 Precautions should be taken when handling any component of the ginkgo tree.

Oral ginkgo supplementation has been implicated in a variety of other cutaneous reactions—from benign to life-threatening. When the ginkgo allergen concentration is too high within the supplement, as has been noted in some formulations, patients have presented with a diffuse morbilliform eruption within 1 or 2 weeks after taking ginkgo.20 One patient—who was not taking any other medication—experienced an episode of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis 48 hours after taking ginkgo.21 Ingestion of ginkgo extract also has been associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.22-24

Other Adverse Reactions

The adverse effects of ginkgo supplement vary widely. In addition to dermatitis, ginkgo supplement can cause headaches, palpitations, tachycardia, vasculitis, nausea, and other symptoms.14

Metabolic Disturbance—One patient taking ginkgo who died after a seizure was found to have subtherapeutic levels of valproate and phenytoin,25 which could be due to ginkgo’s effect on cytochrome p450 enzyme CYP2C19.26 Ginkgo interactions with many cytochrome enzymes have been studied for potential drug interactions. Any other direct effects remain variable and controversial.27,28

Hemorrhage—Another serious effect associated with taking ginkgo supplements is hemorrhage, often in conjunction with warfarin14; however, a meta-analysis indicated that ginkgo generally does not increase the risk of bleeding.29 Other studies have shown that taking ginkgo with warfarin showed no difference in clotting status, and ginkgo with aspirin resulted in no clinically significant difference in bruising, bleeding, or platelet function in an analysis over a period of 1 month.30,31 These findings notwithstanding, pregnant women, surgical patients, and those taking a blood thinner are advised as a general precaution not to take ginkgo extract.

Carcinogenesis—Ginkgo extract has antioxidant properties, but there is evidence that it might act as a carcinogen. An animal study reported by the US National Toxicology Program found that ginkgo induced mutagenic activity in the liver, thyroid, and nose of mice and rats. Over time, rodent liver underwent changes consistent with hepatic enzyme induction.32 More research is needed to clarify the role of ginkgo in this process.

Toxicity by Ingestion—Ginkgo seeds can cause food poisoning due to the compound 4’-O-methylpyridoxine (also known as ginkgotoxin).33 Because methylpyridoxine can cause depletion of pyridoxal phosphate (a form of vitamin B6 necessary for the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid), overconsumption of ginkgo seeds, even when fully cooked, might result in convulsions and even death.33

Nomenclature and Distribution of Plants

Gingko biloba belongs to the Ginkgoaceae family (class Ginkgophytes). The tree originated in China but might no longer exist in a truly wild form. It is grown worldwide for its beauty and longevity. The female ginkgo tree is a gymnosperm, producing fruit with seeds that are not coated by an ovary wall15; male (nonfruiting) trees are preferentially planted because the fruit is surrounded by a pulp that, when dropped, emits a sour smell described variously as rancid butter, vomit, or excrement.5

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The deciduous ginkgo tree has unique fan-shaped leaves and is cultivated for its beauty and resistance to disease (Figure 2).4,34 It is nicknamed the maidenhair tree because the leaves are similar to the pinnae of the maidenhair fern.34 Because G biloba is resistant to pollution, it often is planted along city streets.17 The leaf—5- to 8-cm wide and a symbol of the city of Tokyo, Japan34—grows in clusters (Figure 3)5 and is green but turns yellow before it falls in autumn.34 Leaf veins branch out into the blade without anastomosing.34

Male flowers grow in a catkinlike pattern; female flowers grow on long stems.5 The fruit is small, dark, and shriveled, with a hint of silver4; it typically is 2 to 2.5 cm in diameter and contains the ginkgo nut or seed. The kernel of the ginkgo nut is edible when roasted and is used in traditional Chinese and Japanese cuisine as a dish served on special occasions in autumn.33

Final Thoughts

Given that G biloba is a beautiful, commonly planted ornamental tree, gardeners and landscapers should be aware of the risk for allergic contact dermatitis and use proper protection. Dermatologists should be aware of its cross-reactivity with other common plants such as poison ivy and poison oak to help patients identify the cause of their reactions and avoid the inciting agent. Because ginkgo extract also can cause a cutaneous reaction or interact with other medications, providers should remember to take a thorough medication history that includes herbal medicines and supplements.

- Lyu J. Ginkgo history told by genomes. Nat Plants. 2019;5:1029. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0529-2

- ElSohly MA, Adawadkar PD, Benigni DA, et al. Analogues of poison ivy urushiol. Synthesis and biological activity of disubstituted n-alkylbenzenes. J Med Chem. 1986;29:606-611. doi:10.1021/jm00155a003

- He X, Bernart MW, Nolan GS, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry study of ginkgolic acid in the leaves and fruits of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba). J Chromatogr Sci. 2000;38:169-173. doi:10.1093/chromsci/38.4.169

- Sowers WF, Weary PE, Collins OD, et al. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:452-456. doi:10.1001/archderm.1965.01600110038009

- Tomb RR, Foussereau J, Sell Y. Mini-epidemic of contact dermatitis from ginkgo tree fruit (Ginkgo biloba L.). Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:281-283. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02928.x

- Lepoittevin J-P, Benezra C, Asakawa Y. Allergic contact dermatitis to Ginkgo biloba L.: relationship with urushiol. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:227-230. doi:10.1007/BF00431055

- Yirmibesoglu E, Karahacioglu E, Kilic D, et al. The protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb-761) on radiation-induced dermatitis: an experimental study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:387-394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04253.x

- Jiang L, Su L, Cui H, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract for dementia: a systematic review. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:10-21. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.01.005

- Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of Ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1409-1415. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.11.1409

- Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278:1327-1332. doi:10.1001/jama.278.16.1327

- Koltermann A, Hartkorn A, Koch E, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 increases endothelial nitric oxide production in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1715-1722. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7085-z

- Touvay C, Vilain B, Taylor JE, et al. Proof of the involvement of platelet activating factor (paf-acether) in pulmonary complex immune systems using a specific paf-acether receptor antagonist: BN 52021. Prog Lipid Res. 1986;25:277-288. doi:10.1016/0163-7827(86)90057-3

- Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A. Effectiveness of oral Ginkgo biloba in treating limited, slowly spreading vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:285-287. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01207.x

- Jacobsson I, Jönsson AK, Gerdén B, et al. Spontaneously reported adverse reactions in association with complementary and alternative medicine substances in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:1039-1047. doi:10.1002/pds.1818

- Bolus M. Dermatitis venenata due to Ginkgo berries. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1939;39:530.

- Becker LE, Skipworth GB. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis. JAMA. 1975;231:1162-1163.

- Nakamura T. Ginkgo tree dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:281-282. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb01138.x

- Jiang J, Ding Y, Qian G. Airborne contact dermatitis caused by the sarcotesta of Ginkgo biloba. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:384-385. doi:10.1111/cod.12646

- Hotta E, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N. Allergic contact dermatitis due to ginkgo tree fruit and leaf. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:548-549. doi:10.1684/ejd.2013.2102

- Chiu AE, Lane AT, Kimball AB. Diffuse morbilliform eruption after consumption of Ginkgo biloba supplement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:145-146. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.118545

- Pennisi RS. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis induced by the herbal remedy Ginkgo biloba. Med J Aust. 2006;184:583-584. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00386.x

- Yuste M, Sánchez-Estella J, Santos JC, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:589-592. doi:10.1016/s0001-7310(05)73141-0

- Jeyamani VP, Sabishruthi S, Kavitha S, et al. An illustrative case study on drug induced Steven-Johnson syndrome by Ginkgo biloba. J Clin Res. 2018;2:1-3.

- Davydov L, Stirling AL. Stevens-Johnson syndrome with Ginkgo biloba. J Herbal Pharmacother. 2001;1:65-69. doi:10.1080/J157v01n03_06

- Yin OQP, Tomlinson B, Waye MMY, et al. Pharmacogenetics and herb–drug interactions: experience with Ginkgo biloba and omeprazole. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:841-850. doi:10.1097/00008571-200412000-00007

- Kupiec T, Raj V. Fatal seizures due to potential herb–drug interactions with Ginkgo biloba. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:755-758. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.755

- Zadoyan G, Rokitta D, Klement S, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761® on human cytochrome P450 activity: a cocktail interaction study in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:553-560. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1174-5

- Zhou S-F, Deng Y, Bi H-c, et al. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A by the Ginkgo biloba extract and bilobalides in human and rat primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Lett. 2008;2:60-66. doi:10.2174/187231208783478489

- Kellermann AJ, Kloft C. Is there a risk of bleeding associated with standardized Ginkgo biloba extract therapy? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:490-502. doi:10.1592/phco.31.5.490

- Gardner CD, Zehnder JL, Rigby AJ, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba (EGb 761) and aspirin on platelet aggregation and platelet function analysis among older adults at risk of cardiovascular disease: a randomized clinical trial. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18:787-79. doi:10.1097/MBC.0b013e3282f102b1

- Jiang X, Williams KM, Liauw WS, et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:425-432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02322.x

- Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of Ginkgo biloba extract (CAS No. 90045-36-6) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1/N mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2013:1-183.

- Azuma F, Nokura K, Kako T, et al. An adult case of generalized convulsions caused by the ingestion of Ginkgo biloba seeds with alcohol. Intern Med. 2020;59:1555-1558. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.4196-19

- Cohen PR. Fixed drug eruption to supplement containing Ginkgo biloba and vinpocetine: a case report and review of related cutaneous side effects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:44-47.

An ancient tree of the Ginkgoaceae family, Ginkgo biloba is known as a living fossil because its genome has been identified in fossils older than 200 million years.1 An individual tree can live longer than 1000 years. Originating in China, G biloba (here, “ginkgo”) is cultivated worldwide for its attractive foliage (Figure 1). Ginkgo extract has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine; however, contact with the plant proper can provoke allergic contact dermatitis.

Dermatitis-Inducing Components

The allergenic component of the ginkgo tree is ginkgolic acid, which is structurally similar to urushiol and anacardic acid.2,3 This compound can cause a cross-reaction in a person previously sensitized by contact with other plants. Urushiol is found in poison ivy(Toxicodendron radicans); anacardic acid is found in the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale). Both plants belong to the family Anacardiaceae, commonly known as the cashew family.

Members of Anacardiaceae are the most common causes of plant-induced allergic contact dermatitis and include the cashew tree, mango tree, poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. These plants can cross-react to cause contact dermatitis (Table).3 Patch tests have revealed that some individuals who are sensitive to components of the ginkgo tree also demonstrate sensitivity to poison ivy and poison sumac4,5; countering this finding, Lepoittevin and colleagues6 demonstrated in animal studies that there was no cross-reactivity between ginkgo and urushiol, suggesting that patients with a reported cross-reaction might truly have been previously sensitized to both plants. In general, patients who have a history of a reaction to any Anacardiaceae plant should take precautions when handling them.

Therapeutic Benefit of Ginkgo

Ginkgo extract is sold as the herbal supplement EGB761, which acts as an antioxidant.7 In France, Germany, and China, it is a commonly prescribed herbal medicine.8 It is purported to support memory and attention; studies have shown improvement in cognition and in involvement with activities of daily living for patients with dementia.9,10 Ginkgo extract might lessen peripheral vascular disease and cerebral circulatory disease, having been shown in vitro and in animal models to prevent platelet aggregation induced by platelet-activating factor and to stimulate vasodilation by increasing production of nitric oxide.11,12

Furthermore, purified ginkgo extract might have beneficial effects on skin. A study in rats showed that when intraperitoneal ginkgo extract was given prior to radiation therapy, 100% of rats receiving placebo developed radiation dermatitis vs 13% of those that received ginkgo extract (P<.0001). An excisional skin biopsy showed a decrease in markers of oxidative stress in rats that received ginkgo extract prior to radiation.7

A randomized, double-blind clinical trial showed a significant reduction in disease progression in vitiligo patients assigned to receive ginkgo extract orally compared to placebo (P=.006).13 Research for many possible uses of ginkgo extract is ongoing.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Contact with the fruit of the ginkgo tree can induce allergic contact dermatitis,14 most often as erythematous papules, vesicles, and in some cases edema.5,15

Exposures While Picking Berries—In 1939, Bolus15 reported the case of a patient who presented with edema, erythema, and vesicular lesions involving the hands and face after picking berries from a ginkgo tree. Later, patch testing on this patient, using ginkgo fruit, resulted in burning and stinging that necessitated removal of the patch, suggesting an irritant reaction. This was followed by a vesicular reaction that then developed within 24 hours, which was more consistent with allergy. Similarly, in 1988, a case series of contact dermatitis was reported in 3 patients after gathering ginkgo fruit.5

Incidental Exposure While Walking—In 1965, dermatitis broke out in 35 high school students, mainly affecting exposed portions of the leg, after ginkgo fruit fell and its pulp was exposed on a path at their school.4 Subsequently, patch testing was performed on 29 volunteers—some who had been exposed to ginkgo on that path, others without prior exposure. It was established that testing with ginkgo pulp directly caused an irritant reaction in all students, regardless of prior ginkgo exposure, but all prior ginkgo-exposed students in this study reacted positively to an acetone extract of ginkgo pulp and either poison ivy extract or pentadecylcatechol.4

Systemic Contact After Eating Fruit—An illustrative case of dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis was reported in a man with history of poison oak contact dermatitis who had eaten fruit from a ginkgo tree, suggesting systemic contact dermatitis. Weeks after resolution of symptoms, he reacted positively to ginkgo fruit and poison ivy extracts on patch testing.16

Ginkgo dermatitis tends to resolve upon removal of the inciting agent and application of a topical steroid.8,17 Although many reported cases involve the fruit, allergic contact dermatitis can result from exposure to any part of the plant. In a reported case, a woman developed airborne contact dermatitis from working with sarcotesta of the ginkgo plant.18 Despite wearing rubber gloves, she broke out 1 week after exposure with erythema on the face and arms and severe facial edema.

Ginkgo leaves also can cause allergic contact dermatitis.19 Precautions should be taken when handling any component of the ginkgo tree.

Oral ginkgo supplementation has been implicated in a variety of other cutaneous reactions—from benign to life-threatening. When the ginkgo allergen concentration is too high within the supplement, as has been noted in some formulations, patients have presented with a diffuse morbilliform eruption within 1 or 2 weeks after taking ginkgo.20 One patient—who was not taking any other medication—experienced an episode of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis 48 hours after taking ginkgo.21 Ingestion of ginkgo extract also has been associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.22-24

Other Adverse Reactions

The adverse effects of ginkgo supplement vary widely. In addition to dermatitis, ginkgo supplement can cause headaches, palpitations, tachycardia, vasculitis, nausea, and other symptoms.14

Metabolic Disturbance—One patient taking ginkgo who died after a seizure was found to have subtherapeutic levels of valproate and phenytoin,25 which could be due to ginkgo’s effect on cytochrome p450 enzyme CYP2C19.26 Ginkgo interactions with many cytochrome enzymes have been studied for potential drug interactions. Any other direct effects remain variable and controversial.27,28

Hemorrhage—Another serious effect associated with taking ginkgo supplements is hemorrhage, often in conjunction with warfarin14; however, a meta-analysis indicated that ginkgo generally does not increase the risk of bleeding.29 Other studies have shown that taking ginkgo with warfarin showed no difference in clotting status, and ginkgo with aspirin resulted in no clinically significant difference in bruising, bleeding, or platelet function in an analysis over a period of 1 month.30,31 These findings notwithstanding, pregnant women, surgical patients, and those taking a blood thinner are advised as a general precaution not to take ginkgo extract.

Carcinogenesis—Ginkgo extract has antioxidant properties, but there is evidence that it might act as a carcinogen. An animal study reported by the US National Toxicology Program found that ginkgo induced mutagenic activity in the liver, thyroid, and nose of mice and rats. Over time, rodent liver underwent changes consistent with hepatic enzyme induction.32 More research is needed to clarify the role of ginkgo in this process.

Toxicity by Ingestion—Ginkgo seeds can cause food poisoning due to the compound 4’-O-methylpyridoxine (also known as ginkgotoxin).33 Because methylpyridoxine can cause depletion of pyridoxal phosphate (a form of vitamin B6 necessary for the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid), overconsumption of ginkgo seeds, even when fully cooked, might result in convulsions and even death.33

Nomenclature and Distribution of Plants

Gingko biloba belongs to the Ginkgoaceae family (class Ginkgophytes). The tree originated in China but might no longer exist in a truly wild form. It is grown worldwide for its beauty and longevity. The female ginkgo tree is a gymnosperm, producing fruit with seeds that are not coated by an ovary wall15; male (nonfruiting) trees are preferentially planted because the fruit is surrounded by a pulp that, when dropped, emits a sour smell described variously as rancid butter, vomit, or excrement.5

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The deciduous ginkgo tree has unique fan-shaped leaves and is cultivated for its beauty and resistance to disease (Figure 2).4,34 It is nicknamed the maidenhair tree because the leaves are similar to the pinnae of the maidenhair fern.34 Because G biloba is resistant to pollution, it often is planted along city streets.17 The leaf—5- to 8-cm wide and a symbol of the city of Tokyo, Japan34—grows in clusters (Figure 3)5 and is green but turns yellow before it falls in autumn.34 Leaf veins branch out into the blade without anastomosing.34

Male flowers grow in a catkinlike pattern; female flowers grow on long stems.5 The fruit is small, dark, and shriveled, with a hint of silver4; it typically is 2 to 2.5 cm in diameter and contains the ginkgo nut or seed. The kernel of the ginkgo nut is edible when roasted and is used in traditional Chinese and Japanese cuisine as a dish served on special occasions in autumn.33

Final Thoughts

Given that G biloba is a beautiful, commonly planted ornamental tree, gardeners and landscapers should be aware of the risk for allergic contact dermatitis and use proper protection. Dermatologists should be aware of its cross-reactivity with other common plants such as poison ivy and poison oak to help patients identify the cause of their reactions and avoid the inciting agent. Because ginkgo extract also can cause a cutaneous reaction or interact with other medications, providers should remember to take a thorough medication history that includes herbal medicines and supplements.

An ancient tree of the Ginkgoaceae family, Ginkgo biloba is known as a living fossil because its genome has been identified in fossils older than 200 million years.1 An individual tree can live longer than 1000 years. Originating in China, G biloba (here, “ginkgo”) is cultivated worldwide for its attractive foliage (Figure 1). Ginkgo extract has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine; however, contact with the plant proper can provoke allergic contact dermatitis.

Dermatitis-Inducing Components

The allergenic component of the ginkgo tree is ginkgolic acid, which is structurally similar to urushiol and anacardic acid.2,3 This compound can cause a cross-reaction in a person previously sensitized by contact with other plants. Urushiol is found in poison ivy(Toxicodendron radicans); anacardic acid is found in the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale). Both plants belong to the family Anacardiaceae, commonly known as the cashew family.

Members of Anacardiaceae are the most common causes of plant-induced allergic contact dermatitis and include the cashew tree, mango tree, poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. These plants can cross-react to cause contact dermatitis (Table).3 Patch tests have revealed that some individuals who are sensitive to components of the ginkgo tree also demonstrate sensitivity to poison ivy and poison sumac4,5; countering this finding, Lepoittevin and colleagues6 demonstrated in animal studies that there was no cross-reactivity between ginkgo and urushiol, suggesting that patients with a reported cross-reaction might truly have been previously sensitized to both plants. In general, patients who have a history of a reaction to any Anacardiaceae plant should take precautions when handling them.

Therapeutic Benefit of Ginkgo

Ginkgo extract is sold as the herbal supplement EGB761, which acts as an antioxidant.7 In France, Germany, and China, it is a commonly prescribed herbal medicine.8 It is purported to support memory and attention; studies have shown improvement in cognition and in involvement with activities of daily living for patients with dementia.9,10 Ginkgo extract might lessen peripheral vascular disease and cerebral circulatory disease, having been shown in vitro and in animal models to prevent platelet aggregation induced by platelet-activating factor and to stimulate vasodilation by increasing production of nitric oxide.11,12

Furthermore, purified ginkgo extract might have beneficial effects on skin. A study in rats showed that when intraperitoneal ginkgo extract was given prior to radiation therapy, 100% of rats receiving placebo developed radiation dermatitis vs 13% of those that received ginkgo extract (P<.0001). An excisional skin biopsy showed a decrease in markers of oxidative stress in rats that received ginkgo extract prior to radiation.7

A randomized, double-blind clinical trial showed a significant reduction in disease progression in vitiligo patients assigned to receive ginkgo extract orally compared to placebo (P=.006).13 Research for many possible uses of ginkgo extract is ongoing.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Contact with the fruit of the ginkgo tree can induce allergic contact dermatitis,14 most often as erythematous papules, vesicles, and in some cases edema.5,15

Exposures While Picking Berries—In 1939, Bolus15 reported the case of a patient who presented with edema, erythema, and vesicular lesions involving the hands and face after picking berries from a ginkgo tree. Later, patch testing on this patient, using ginkgo fruit, resulted in burning and stinging that necessitated removal of the patch, suggesting an irritant reaction. This was followed by a vesicular reaction that then developed within 24 hours, which was more consistent with allergy. Similarly, in 1988, a case series of contact dermatitis was reported in 3 patients after gathering ginkgo fruit.5

Incidental Exposure While Walking—In 1965, dermatitis broke out in 35 high school students, mainly affecting exposed portions of the leg, after ginkgo fruit fell and its pulp was exposed on a path at their school.4 Subsequently, patch testing was performed on 29 volunteers—some who had been exposed to ginkgo on that path, others without prior exposure. It was established that testing with ginkgo pulp directly caused an irritant reaction in all students, regardless of prior ginkgo exposure, but all prior ginkgo-exposed students in this study reacted positively to an acetone extract of ginkgo pulp and either poison ivy extract or pentadecylcatechol.4

Systemic Contact After Eating Fruit—An illustrative case of dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis was reported in a man with history of poison oak contact dermatitis who had eaten fruit from a ginkgo tree, suggesting systemic contact dermatitis. Weeks after resolution of symptoms, he reacted positively to ginkgo fruit and poison ivy extracts on patch testing.16

Ginkgo dermatitis tends to resolve upon removal of the inciting agent and application of a topical steroid.8,17 Although many reported cases involve the fruit, allergic contact dermatitis can result from exposure to any part of the plant. In a reported case, a woman developed airborne contact dermatitis from working with sarcotesta of the ginkgo plant.18 Despite wearing rubber gloves, she broke out 1 week after exposure with erythema on the face and arms and severe facial edema.

Ginkgo leaves also can cause allergic contact dermatitis.19 Precautions should be taken when handling any component of the ginkgo tree.

Oral ginkgo supplementation has been implicated in a variety of other cutaneous reactions—from benign to life-threatening. When the ginkgo allergen concentration is too high within the supplement, as has been noted in some formulations, patients have presented with a diffuse morbilliform eruption within 1 or 2 weeks after taking ginkgo.20 One patient—who was not taking any other medication—experienced an episode of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis 48 hours after taking ginkgo.21 Ingestion of ginkgo extract also has been associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.22-24

Other Adverse Reactions

The adverse effects of ginkgo supplement vary widely. In addition to dermatitis, ginkgo supplement can cause headaches, palpitations, tachycardia, vasculitis, nausea, and other symptoms.14

Metabolic Disturbance—One patient taking ginkgo who died after a seizure was found to have subtherapeutic levels of valproate and phenytoin,25 which could be due to ginkgo’s effect on cytochrome p450 enzyme CYP2C19.26 Ginkgo interactions with many cytochrome enzymes have been studied for potential drug interactions. Any other direct effects remain variable and controversial.27,28

Hemorrhage—Another serious effect associated with taking ginkgo supplements is hemorrhage, often in conjunction with warfarin14; however, a meta-analysis indicated that ginkgo generally does not increase the risk of bleeding.29 Other studies have shown that taking ginkgo with warfarin showed no difference in clotting status, and ginkgo with aspirin resulted in no clinically significant difference in bruising, bleeding, or platelet function in an analysis over a period of 1 month.30,31 These findings notwithstanding, pregnant women, surgical patients, and those taking a blood thinner are advised as a general precaution not to take ginkgo extract.

Carcinogenesis—Ginkgo extract has antioxidant properties, but there is evidence that it might act as a carcinogen. An animal study reported by the US National Toxicology Program found that ginkgo induced mutagenic activity in the liver, thyroid, and nose of mice and rats. Over time, rodent liver underwent changes consistent with hepatic enzyme induction.32 More research is needed to clarify the role of ginkgo in this process.

Toxicity by Ingestion—Ginkgo seeds can cause food poisoning due to the compound 4’-O-methylpyridoxine (also known as ginkgotoxin).33 Because methylpyridoxine can cause depletion of pyridoxal phosphate (a form of vitamin B6 necessary for the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid), overconsumption of ginkgo seeds, even when fully cooked, might result in convulsions and even death.33

Nomenclature and Distribution of Plants

Gingko biloba belongs to the Ginkgoaceae family (class Ginkgophytes). The tree originated in China but might no longer exist in a truly wild form. It is grown worldwide for its beauty and longevity. The female ginkgo tree is a gymnosperm, producing fruit with seeds that are not coated by an ovary wall15; male (nonfruiting) trees are preferentially planted because the fruit is surrounded by a pulp that, when dropped, emits a sour smell described variously as rancid butter, vomit, or excrement.5

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The deciduous ginkgo tree has unique fan-shaped leaves and is cultivated for its beauty and resistance to disease (Figure 2).4,34 It is nicknamed the maidenhair tree because the leaves are similar to the pinnae of the maidenhair fern.34 Because G biloba is resistant to pollution, it often is planted along city streets.17 The leaf—5- to 8-cm wide and a symbol of the city of Tokyo, Japan34—grows in clusters (Figure 3)5 and is green but turns yellow before it falls in autumn.34 Leaf veins branch out into the blade without anastomosing.34

Male flowers grow in a catkinlike pattern; female flowers grow on long stems.5 The fruit is small, dark, and shriveled, with a hint of silver4; it typically is 2 to 2.5 cm in diameter and contains the ginkgo nut or seed. The kernel of the ginkgo nut is edible when roasted and is used in traditional Chinese and Japanese cuisine as a dish served on special occasions in autumn.33

Final Thoughts

Given that G biloba is a beautiful, commonly planted ornamental tree, gardeners and landscapers should be aware of the risk for allergic contact dermatitis and use proper protection. Dermatologists should be aware of its cross-reactivity with other common plants such as poison ivy and poison oak to help patients identify the cause of their reactions and avoid the inciting agent. Because ginkgo extract also can cause a cutaneous reaction or interact with other medications, providers should remember to take a thorough medication history that includes herbal medicines and supplements.

- Lyu J. Ginkgo history told by genomes. Nat Plants. 2019;5:1029. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0529-2

- ElSohly MA, Adawadkar PD, Benigni DA, et al. Analogues of poison ivy urushiol. Synthesis and biological activity of disubstituted n-alkylbenzenes. J Med Chem. 1986;29:606-611. doi:10.1021/jm00155a003

- He X, Bernart MW, Nolan GS, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry study of ginkgolic acid in the leaves and fruits of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba). J Chromatogr Sci. 2000;38:169-173. doi:10.1093/chromsci/38.4.169

- Sowers WF, Weary PE, Collins OD, et al. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:452-456. doi:10.1001/archderm.1965.01600110038009

- Tomb RR, Foussereau J, Sell Y. Mini-epidemic of contact dermatitis from ginkgo tree fruit (Ginkgo biloba L.). Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:281-283. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02928.x

- Lepoittevin J-P, Benezra C, Asakawa Y. Allergic contact dermatitis to Ginkgo biloba L.: relationship with urushiol. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:227-230. doi:10.1007/BF00431055

- Yirmibesoglu E, Karahacioglu E, Kilic D, et al. The protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb-761) on radiation-induced dermatitis: an experimental study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:387-394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04253.x

- Jiang L, Su L, Cui H, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract for dementia: a systematic review. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:10-21. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.01.005

- Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of Ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1409-1415. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.11.1409

- Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278:1327-1332. doi:10.1001/jama.278.16.1327

- Koltermann A, Hartkorn A, Koch E, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 increases endothelial nitric oxide production in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1715-1722. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7085-z

- Touvay C, Vilain B, Taylor JE, et al. Proof of the involvement of platelet activating factor (paf-acether) in pulmonary complex immune systems using a specific paf-acether receptor antagonist: BN 52021. Prog Lipid Res. 1986;25:277-288. doi:10.1016/0163-7827(86)90057-3

- Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A. Effectiveness of oral Ginkgo biloba in treating limited, slowly spreading vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:285-287. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01207.x

- Jacobsson I, Jönsson AK, Gerdén B, et al. Spontaneously reported adverse reactions in association with complementary and alternative medicine substances in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:1039-1047. doi:10.1002/pds.1818

- Bolus M. Dermatitis venenata due to Ginkgo berries. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1939;39:530.

- Becker LE, Skipworth GB. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis. JAMA. 1975;231:1162-1163.

- Nakamura T. Ginkgo tree dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:281-282. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb01138.x

- Jiang J, Ding Y, Qian G. Airborne contact dermatitis caused by the sarcotesta of Ginkgo biloba. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:384-385. doi:10.1111/cod.12646

- Hotta E, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N. Allergic contact dermatitis due to ginkgo tree fruit and leaf. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:548-549. doi:10.1684/ejd.2013.2102

- Chiu AE, Lane AT, Kimball AB. Diffuse morbilliform eruption after consumption of Ginkgo biloba supplement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:145-146. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.118545

- Pennisi RS. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis induced by the herbal remedy Ginkgo biloba. Med J Aust. 2006;184:583-584. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00386.x

- Yuste M, Sánchez-Estella J, Santos JC, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:589-592. doi:10.1016/s0001-7310(05)73141-0

- Jeyamani VP, Sabishruthi S, Kavitha S, et al. An illustrative case study on drug induced Steven-Johnson syndrome by Ginkgo biloba. J Clin Res. 2018;2:1-3.

- Davydov L, Stirling AL. Stevens-Johnson syndrome with Ginkgo biloba. J Herbal Pharmacother. 2001;1:65-69. doi:10.1080/J157v01n03_06

- Yin OQP, Tomlinson B, Waye MMY, et al. Pharmacogenetics and herb–drug interactions: experience with Ginkgo biloba and omeprazole. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:841-850. doi:10.1097/00008571-200412000-00007

- Kupiec T, Raj V. Fatal seizures due to potential herb–drug interactions with Ginkgo biloba. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:755-758. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.755

- Zadoyan G, Rokitta D, Klement S, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761® on human cytochrome P450 activity: a cocktail interaction study in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:553-560. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1174-5

- Zhou S-F, Deng Y, Bi H-c, et al. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A by the Ginkgo biloba extract and bilobalides in human and rat primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Lett. 2008;2:60-66. doi:10.2174/187231208783478489

- Kellermann AJ, Kloft C. Is there a risk of bleeding associated with standardized Ginkgo biloba extract therapy? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:490-502. doi:10.1592/phco.31.5.490

- Gardner CD, Zehnder JL, Rigby AJ, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba (EGb 761) and aspirin on platelet aggregation and platelet function analysis among older adults at risk of cardiovascular disease: a randomized clinical trial. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18:787-79. doi:10.1097/MBC.0b013e3282f102b1

- Jiang X, Williams KM, Liauw WS, et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:425-432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02322.x

- Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of Ginkgo biloba extract (CAS No. 90045-36-6) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1/N mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2013:1-183.

- Azuma F, Nokura K, Kako T, et al. An adult case of generalized convulsions caused by the ingestion of Ginkgo biloba seeds with alcohol. Intern Med. 2020;59:1555-1558. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.4196-19

- Cohen PR. Fixed drug eruption to supplement containing Ginkgo biloba and vinpocetine: a case report and review of related cutaneous side effects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:44-47.

- Lyu J. Ginkgo history told by genomes. Nat Plants. 2019;5:1029. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0529-2

- ElSohly MA, Adawadkar PD, Benigni DA, et al. Analogues of poison ivy urushiol. Synthesis and biological activity of disubstituted n-alkylbenzenes. J Med Chem. 1986;29:606-611. doi:10.1021/jm00155a003

- He X, Bernart MW, Nolan GS, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry study of ginkgolic acid in the leaves and fruits of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba). J Chromatogr Sci. 2000;38:169-173. doi:10.1093/chromsci/38.4.169

- Sowers WF, Weary PE, Collins OD, et al. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:452-456. doi:10.1001/archderm.1965.01600110038009

- Tomb RR, Foussereau J, Sell Y. Mini-epidemic of contact dermatitis from ginkgo tree fruit (Ginkgo biloba L.). Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:281-283. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02928.x

- Lepoittevin J-P, Benezra C, Asakawa Y. Allergic contact dermatitis to Ginkgo biloba L.: relationship with urushiol. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:227-230. doi:10.1007/BF00431055

- Yirmibesoglu E, Karahacioglu E, Kilic D, et al. The protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb-761) on radiation-induced dermatitis: an experimental study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:387-394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04253.x

- Jiang L, Su L, Cui H, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract for dementia: a systematic review. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:10-21. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.01.005

- Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of Ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1409-1415. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.11.1409

- Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278:1327-1332. doi:10.1001/jama.278.16.1327

- Koltermann A, Hartkorn A, Koch E, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 increases endothelial nitric oxide production in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1715-1722. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7085-z

- Touvay C, Vilain B, Taylor JE, et al. Proof of the involvement of platelet activating factor (paf-acether) in pulmonary complex immune systems using a specific paf-acether receptor antagonist: BN 52021. Prog Lipid Res. 1986;25:277-288. doi:10.1016/0163-7827(86)90057-3

- Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A. Effectiveness of oral Ginkgo biloba in treating limited, slowly spreading vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:285-287. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01207.x

- Jacobsson I, Jönsson AK, Gerdén B, et al. Spontaneously reported adverse reactions in association with complementary and alternative medicine substances in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:1039-1047. doi:10.1002/pds.1818

- Bolus M. Dermatitis venenata due to Ginkgo berries. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1939;39:530.

- Becker LE, Skipworth GB. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis. JAMA. 1975;231:1162-1163.

- Nakamura T. Ginkgo tree dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:281-282. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb01138.x

- Jiang J, Ding Y, Qian G. Airborne contact dermatitis caused by the sarcotesta of Ginkgo biloba. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:384-385. doi:10.1111/cod.12646

- Hotta E, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N. Allergic contact dermatitis due to ginkgo tree fruit and leaf. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:548-549. doi:10.1684/ejd.2013.2102

- Chiu AE, Lane AT, Kimball AB. Diffuse morbilliform eruption after consumption of Ginkgo biloba supplement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:145-146. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.118545

- Pennisi RS. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis induced by the herbal remedy Ginkgo biloba. Med J Aust. 2006;184:583-584. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00386.x

- Yuste M, Sánchez-Estella J, Santos JC, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:589-592. doi:10.1016/s0001-7310(05)73141-0

- Jeyamani VP, Sabishruthi S, Kavitha S, et al. An illustrative case study on drug induced Steven-Johnson syndrome by Ginkgo biloba. J Clin Res. 2018;2:1-3.

- Davydov L, Stirling AL. Stevens-Johnson syndrome with Ginkgo biloba. J Herbal Pharmacother. 2001;1:65-69. doi:10.1080/J157v01n03_06

- Yin OQP, Tomlinson B, Waye MMY, et al. Pharmacogenetics and herb–drug interactions: experience with Ginkgo biloba and omeprazole. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:841-850. doi:10.1097/00008571-200412000-00007

- Kupiec T, Raj V. Fatal seizures due to potential herb–drug interactions with Ginkgo biloba. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:755-758. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.755

- Zadoyan G, Rokitta D, Klement S, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761® on human cytochrome P450 activity: a cocktail interaction study in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:553-560. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1174-5

- Zhou S-F, Deng Y, Bi H-c, et al. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A by the Ginkgo biloba extract and bilobalides in human and rat primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Lett. 2008;2:60-66. doi:10.2174/187231208783478489

- Kellermann AJ, Kloft C. Is there a risk of bleeding associated with standardized Ginkgo biloba extract therapy? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:490-502. doi:10.1592/phco.31.5.490

- Gardner CD, Zehnder JL, Rigby AJ, et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba (EGb 761) and aspirin on platelet aggregation and platelet function analysis among older adults at risk of cardiovascular disease: a randomized clinical trial. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18:787-79. doi:10.1097/MBC.0b013e3282f102b1

- Jiang X, Williams KM, Liauw WS, et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:425-432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02322.x

- Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of Ginkgo biloba extract (CAS No. 90045-36-6) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1/N mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2013:1-183.

- Azuma F, Nokura K, Kako T, et al. An adult case of generalized convulsions caused by the ingestion of Ginkgo biloba seeds with alcohol. Intern Med. 2020;59:1555-1558. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.4196-19

- Cohen PR. Fixed drug eruption to supplement containing Ginkgo biloba and vinpocetine: a case report and review of related cutaneous side effects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:44-47.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Contact with the Ginkgo biloba tree can cause allergic contact dermatitis; ingestion can cause systemic dermatitis in a previously sensitized patient.

- Ginkgo biloba can cross-react with plants of the family Anacardiaceae, such as poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, cashew tree, and mango.

- Ginkgo extract is widely considered safe for use; however, dermatologists should be aware that it can cause systemic dermatitis and serious adverse effects, including internal hemorrhage and convulsions.

Vascular Plaque in a Pregnant Patient With a History of Breast Cancer

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

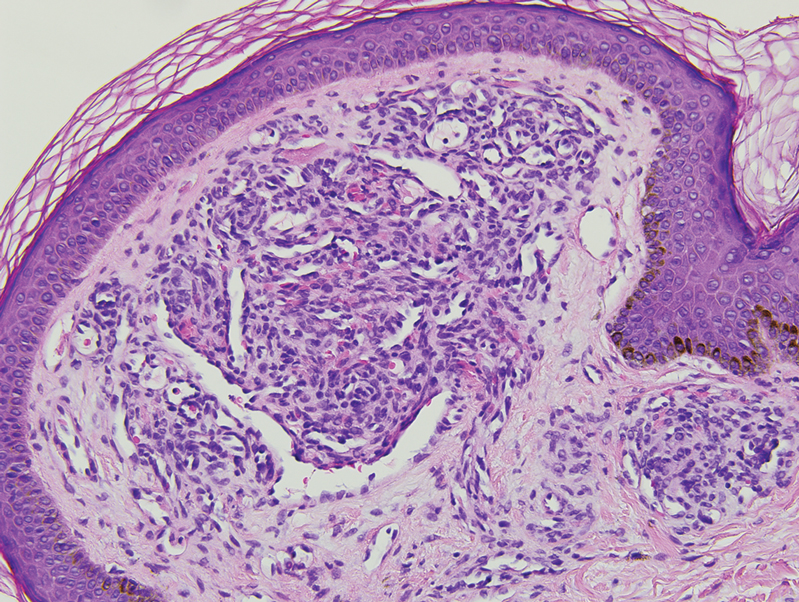

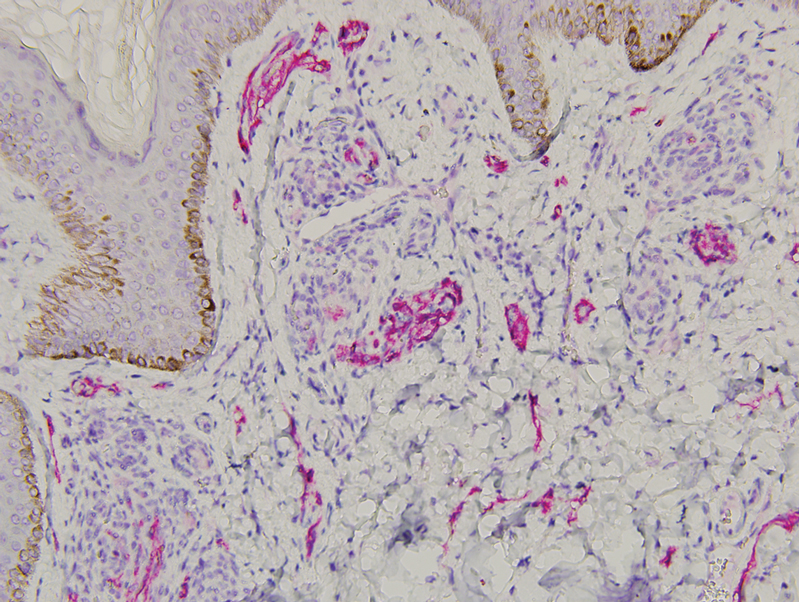

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

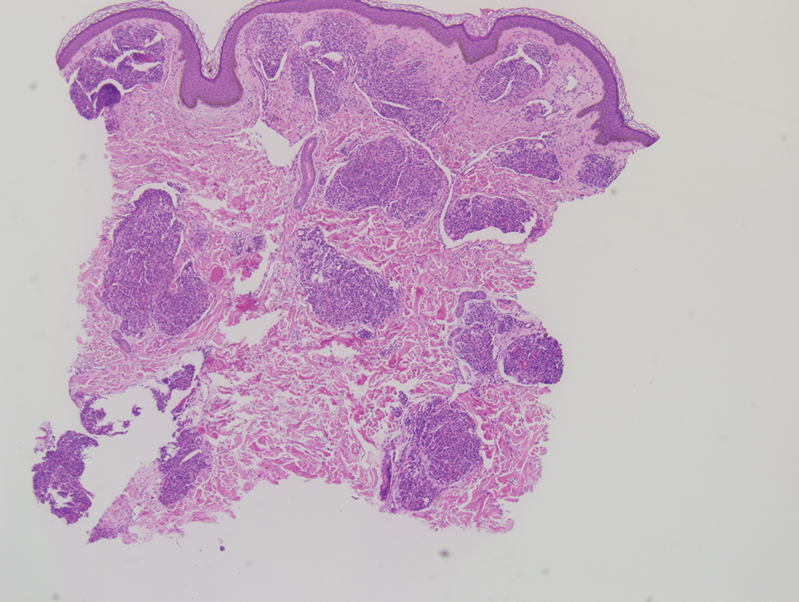

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

A 31-year-old woman at 34 weeks’ gestation presented with skin discoloration of the anterior neck of 7 months’ duration. Her pregnancy had been complicated by a diagnosis of invasive papillary carcinoma of the breast with unilateral complete mastectomy and negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in the first trimester. The lesion was tender, darkening, and rapidly enlarging. Physical examination demonstrated a linear, violaceous, vascular, and indurated plaque with microvesiculation that was 3.5 cm in width. She had no history of blistering sunburns, frequent UV exposure, or skin cancer.