User login

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Observation Care

Many conditions once treated during an “inpatient” hospital stay are currently treated during an “observation” stay (OBS). Although the care remains the same, physician billing is different and requires close attention to admission details for effective charge capture.

Let’s take a look at a typical OBS scenario. A 65-year-old female with longstanding diabetes presents to the ED at 10 p.m. with palpitations, lightheadedness, mild disorientation, and elevated blood sugar. The hospitalist admits the patient to observation, treats her for dehydration, and discharges her the next day. Before billing, the hospitalist should consider the following factors.

Physician of Record

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation; indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. The attending reports the initial patient encounter with the most appropriate initial observation-care code, as reflected by the documentation:1

- 99218: Initial observation care, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward/low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99219: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99220: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of high severity.

While other physicians (e.g., specialists) might be involved in the patient’s care, only the attending physician reports codes 99218-99220. Specialists typically are called to an OBS case for their opinion or advice but do not function as the attending of record. Billing for the specialist (consultation) service depends upon the payor.

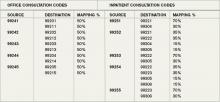

For a non-Medicare patient who pays for consultation codes, the specialist reports an outpatient consultation code (99241-99245) for the appropriately documented service. Conversely, Medicare no longer recognizes consultation codes, and specialists must report either a new patient visit code (99201-99205) or established patient visit code (99212-99215) for Medicare beneficiaries.

Selection of the new or established patient codes follows the “three-year rule”: A “new patient” has not received any face-to-face services (e.g., visit or procedure) in any location from any physician within the same group and same specialty within the past three years.2 There could be occasion when a hospitalist is not the attending of record but is asked to provide their opinion, and must report one of the “non-OBS” codes.

The attending of record is permitted to report a discharge service as long as this service occurs on a calendar day different from the admission service (as in the listed scenario). The attending documents the face-to-face discharge service and any pertinent clinical details, and reports 99217 (observation-care discharge-day management).

Length of Stay

Observation-care services typically do not exceed 24 hours and two calendar days. Observation care for more than 48 hours without inpatient admission is not considered medically necessary but might be payable after medical review. Should the OBS stay span more than two calendar days (as might be the case with “downgraded” hospitalizations), hospitalists should report established patient visit codes (99212-99215) for the calendar day(s) between the admission service (99218-99220) and the discharge service (99217).3 The physician must provide and document a face-to-face encounter on each date of service for which a claim was submitted.

A more likely occurrence is the admission and discharge from OBS on the same calendar date. The attending of record reports the code that corresponds to the patient’s length of stay (LOS). If the total LOS is less than eight hours, the attending only reports standard OBS codes (99218-99220). The hospitalist does not separately report the OBS discharge service (99217), even though the documentation must reflect the attending discharge order and corresponding discharge plan. If the total duration of the patient’s stay lasts more than eight hours and does not overlap two calendar days, the attending reports the same-day admit/discharge codes:1

- 99234: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward or low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99235: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99236: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of high severity.

OBS discharge service (99217) is not separately reported with 99234-99236 because these codes are valued to include the discharge component (e.g., the comprehensive service, 99236 [4.26 wRVU, $211], is equivalent to its components, 99220 [2.99 wRVU, $148] and 99217 [1.28 wRVU, $68]). The attending must document the total duration of the stay, as well as the face-to-face service and the corresponding details of each service component (i.e., both an admission and discharge note).3TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010:11-16.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.7A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8C. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8D. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 1, Section 50.3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c01.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Many conditions once treated during an “inpatient” hospital stay are currently treated during an “observation” stay (OBS). Although the care remains the same, physician billing is different and requires close attention to admission details for effective charge capture.

Let’s take a look at a typical OBS scenario. A 65-year-old female with longstanding diabetes presents to the ED at 10 p.m. with palpitations, lightheadedness, mild disorientation, and elevated blood sugar. The hospitalist admits the patient to observation, treats her for dehydration, and discharges her the next day. Before billing, the hospitalist should consider the following factors.

Physician of Record

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation; indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. The attending reports the initial patient encounter with the most appropriate initial observation-care code, as reflected by the documentation:1

- 99218: Initial observation care, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward/low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99219: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99220: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of high severity.

While other physicians (e.g., specialists) might be involved in the patient’s care, only the attending physician reports codes 99218-99220. Specialists typically are called to an OBS case for their opinion or advice but do not function as the attending of record. Billing for the specialist (consultation) service depends upon the payor.

For a non-Medicare patient who pays for consultation codes, the specialist reports an outpatient consultation code (99241-99245) for the appropriately documented service. Conversely, Medicare no longer recognizes consultation codes, and specialists must report either a new patient visit code (99201-99205) or established patient visit code (99212-99215) for Medicare beneficiaries.

Selection of the new or established patient codes follows the “three-year rule”: A “new patient” has not received any face-to-face services (e.g., visit or procedure) in any location from any physician within the same group and same specialty within the past three years.2 There could be occasion when a hospitalist is not the attending of record but is asked to provide their opinion, and must report one of the “non-OBS” codes.

The attending of record is permitted to report a discharge service as long as this service occurs on a calendar day different from the admission service (as in the listed scenario). The attending documents the face-to-face discharge service and any pertinent clinical details, and reports 99217 (observation-care discharge-day management).

Length of Stay

Observation-care services typically do not exceed 24 hours and two calendar days. Observation care for more than 48 hours without inpatient admission is not considered medically necessary but might be payable after medical review. Should the OBS stay span more than two calendar days (as might be the case with “downgraded” hospitalizations), hospitalists should report established patient visit codes (99212-99215) for the calendar day(s) between the admission service (99218-99220) and the discharge service (99217).3 The physician must provide and document a face-to-face encounter on each date of service for which a claim was submitted.

A more likely occurrence is the admission and discharge from OBS on the same calendar date. The attending of record reports the code that corresponds to the patient’s length of stay (LOS). If the total LOS is less than eight hours, the attending only reports standard OBS codes (99218-99220). The hospitalist does not separately report the OBS discharge service (99217), even though the documentation must reflect the attending discharge order and corresponding discharge plan. If the total duration of the patient’s stay lasts more than eight hours and does not overlap two calendar days, the attending reports the same-day admit/discharge codes:1

- 99234: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward or low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99235: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99236: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of high severity.

OBS discharge service (99217) is not separately reported with 99234-99236 because these codes are valued to include the discharge component (e.g., the comprehensive service, 99236 [4.26 wRVU, $211], is equivalent to its components, 99220 [2.99 wRVU, $148] and 99217 [1.28 wRVU, $68]). The attending must document the total duration of the stay, as well as the face-to-face service and the corresponding details of each service component (i.e., both an admission and discharge note).3TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010:11-16.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.7A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8C. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8D. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 1, Section 50.3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c01.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Many conditions once treated during an “inpatient” hospital stay are currently treated during an “observation” stay (OBS). Although the care remains the same, physician billing is different and requires close attention to admission details for effective charge capture.

Let’s take a look at a typical OBS scenario. A 65-year-old female with longstanding diabetes presents to the ED at 10 p.m. with palpitations, lightheadedness, mild disorientation, and elevated blood sugar. The hospitalist admits the patient to observation, treats her for dehydration, and discharges her the next day. Before billing, the hospitalist should consider the following factors.

Physician of Record

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation; indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. The attending reports the initial patient encounter with the most appropriate initial observation-care code, as reflected by the documentation:1

- 99218: Initial observation care, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward/low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99219: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99220: Initial observation care, requiring both a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually, the problem(s) is of high severity.

While other physicians (e.g., specialists) might be involved in the patient’s care, only the attending physician reports codes 99218-99220. Specialists typically are called to an OBS case for their opinion or advice but do not function as the attending of record. Billing for the specialist (consultation) service depends upon the payor.

For a non-Medicare patient who pays for consultation codes, the specialist reports an outpatient consultation code (99241-99245) for the appropriately documented service. Conversely, Medicare no longer recognizes consultation codes, and specialists must report either a new patient visit code (99201-99205) or established patient visit code (99212-99215) for Medicare beneficiaries.

Selection of the new or established patient codes follows the “three-year rule”: A “new patient” has not received any face-to-face services (e.g., visit or procedure) in any location from any physician within the same group and same specialty within the past three years.2 There could be occasion when a hospitalist is not the attending of record but is asked to provide their opinion, and must report one of the “non-OBS” codes.

The attending of record is permitted to report a discharge service as long as this service occurs on a calendar day different from the admission service (as in the listed scenario). The attending documents the face-to-face discharge service and any pertinent clinical details, and reports 99217 (observation-care discharge-day management).

Length of Stay

Observation-care services typically do not exceed 24 hours and two calendar days. Observation care for more than 48 hours without inpatient admission is not considered medically necessary but might be payable after medical review. Should the OBS stay span more than two calendar days (as might be the case with “downgraded” hospitalizations), hospitalists should report established patient visit codes (99212-99215) for the calendar day(s) between the admission service (99218-99220) and the discharge service (99217).3 The physician must provide and document a face-to-face encounter on each date of service for which a claim was submitted.

A more likely occurrence is the admission and discharge from OBS on the same calendar date. The attending of record reports the code that corresponds to the patient’s length of stay (LOS). If the total LOS is less than eight hours, the attending only reports standard OBS codes (99218-99220). The hospitalist does not separately report the OBS discharge service (99217), even though the documentation must reflect the attending discharge order and corresponding discharge plan. If the total duration of the patient’s stay lasts more than eight hours and does not overlap two calendar days, the attending reports the same-day admit/discharge codes:1

- 99234: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring both a detailed or comprehensive history and exam, and straightforward or low-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of low severity.

- 99235: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and moderate-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of moderate severity.

- 99236: Observation or inpatient care, same date admission and discharge, requiring a comprehensive history and exam, and high-complexity medical decision-making. Usually the presenting problem(s) is of high severity.

OBS discharge service (99217) is not separately reported with 99234-99236 because these codes are valued to include the discharge component (e.g., the comprehensive service, 99236 [4.26 wRVU, $211], is equivalent to its components, 99220 [2.99 wRVU, $148] and 99217 [1.28 wRVU, $68]). The attending must document the total duration of the stay, as well as the face-to-face service and the corresponding details of each service component (i.e., both an admission and discharge note).3TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010:11-16.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.7A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8C. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8D. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 1, Section 50.3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c01.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Discharge Services

Discharge day management services (99238-99239) seem unlikely to cause confusion in the physician community; however, continued requests for documentation involving these CPT codes prove the opposite.

Here’s an example of how a billing error might be made for discharge day management services. A patient with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease is stable for discharge. The patient is being transferred to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Dr. Aardsma prepares the patient for hospital discharge, and Dr. Broxton admits the patient to the SNF later that day. Dr. Aardsma and Dr. Broxton are members of the same group practice, with the same specialty designation. Can both physicians report their services?

Key Elements

Consider the basic billing principles of discharge services: what, who, and when.

Hospital discharge day management codes are used to report the physician’s total duration of time spent preparing the patient for discharge. These codes include, as appropriate:

- Final examination of the patient;

- Discussion of the hospital stay, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous;

- Instructions for continuing care to all relevant caregivers; and

- Preparation of discharge records, prescriptions, and referral forms.1

Hospitalists should report one discharge code per hospitalization, but only when the service occurs after the initial date of admission: 99238, hospital discharge day management, 30 minutes or less; or 99239, hospital discharge day management, more than 30 minutes.1,2 Select one of the two codes, depending upon the cumulative discharge service time provided on the patient’s hospital unit/floor during a single calendar day. Do not count time for services performed outside of the patient’s unit or floor (i.e., calls to the receiving physician/facility made from the physician’s private office) or services performed after the patient physically leaves the hospital.

Physician documentation must refer to the discharge status, as well as other clinically relevant information. Don’t be misled into believing that the presence of a discharge summary alone satisfies documentation requirements. In addition to the discharge groundwork, hospitalists must physically see the patient on the day he or she reports discharge management. Discharge summaries are not always useful in noting the physician’s required face-to-face encounter with the patient. Simply state, “Patient seen and examined by me on discharge day.”

Alternatively, hospitalists can elect to include details of a discharge day exam. Although a final exam isn’t mandatory for billing 99238-99239, it is the best justification of a face-to-face encounter on discharge day. Documentation of the time is required when reporting 99239 (e.g., discharge time >30 minutes). Time isn’t typically included in a discharge summary, and upon post-payment payor review, a claim involving 99239 without documented time in the patient’s medical record might result in either a service reduction to the lower level of care (99238) or a request for payment refund.3 Physicians can document all necessary details in the formal summary or a progress note.

Transfers of Care

The admitting physician or group is responsible for performing discharge services unless a formal transfer of care occurs, such as the patient’s transfer from the ICU to the standard medical floor as the patient’s condition improves. Without this transfer of care, comanaging physicians should merely report subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233) for the final patient encounter. An example of this is surgical comanagement: If a surgeon is identified as the attending of record, they are responsible for postoperative management of the patient, including discharge services.4,5 Providers in a different group or specialty report 99231-99233 for their medically necessary care.

As with all other time-based services, only the billing provider’s time counts. Discharge-related services performed by residents, students, or ancillary staff (i.e., RNs) do not count toward the physician’s discharge service time. Report the date of the physician’s actual discharge visit even if the patient leaves the facility on a different calendar date—for example, if a patient leaves the next day due to availability of the receiving facility.

Pronouncement of Death

Physicians might not realize that they can report discharge day management codes for pronouncement of death.7 Only the hospitalist who performs the pronouncement is allowed to report this service on the date pronouncement occurred, even if the paperwork is delayed to a subsequent date. Completion of the death certificate alone is not sufficient for billing. Hospitalists must “examine” the patient, thus satisfying the “face to face” visit requirement.

Additional services (e.g., speaking with family members, speaking with healthcare providers, filling out the necessary documentation) count toward the cumulative discharge service time, if performed on the patient’s unit or floor. Document the cumulative time when reporting 99239.

Back to the Case

Typical billing and payment rules mandate the reporting of only one E/M service per specialty, per patient, per day. One of the few exceptions involves reporting a hospital discharge code (99238-99239) with initial nursing facility care (99304-99306). Either the same physician or different physicians from the same group and specialty can report the hospital discharge and the nursing facility admission on the same day. When the same physician or group discharges the patient from any other location (e.g., observation unit) on the same day, report only one service: either the observation discharge (99217) or the initial nursing facility care (99304-99306).

When the same physician or group discharges a patient from the hospital and admits the patient to a facility other than a nursing facility on the same day, report only one service: either the hospital discharge (99228-99239) or the admission care (e.g., long-term acute-care hospital: 99221-99223). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2010.

- Highmark Medicare Services Provider Bulletins: Hospital Discharge Day Management Codes 99238 and 99239. Highmark Medicare Services Web site. Available at: www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/bulletins/partb/news02212008a.html. Accessed March 4, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.1A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.3B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site, Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.2E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1d. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Reporting inpatient hospital evaluation and management (E/M) services that could be described by current procedural terminology (CPT) consultation codes. Cigna Government Services Web site. Available at: www.cignagovernmentservices.com/partb/pubs/news/2010/0210/cope11694.html. Accessed March 5, 2010.

Discharge day management services (99238-99239) seem unlikely to cause confusion in the physician community; however, continued requests for documentation involving these CPT codes prove the opposite.

Here’s an example of how a billing error might be made for discharge day management services. A patient with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease is stable for discharge. The patient is being transferred to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Dr. Aardsma prepares the patient for hospital discharge, and Dr. Broxton admits the patient to the SNF later that day. Dr. Aardsma and Dr. Broxton are members of the same group practice, with the same specialty designation. Can both physicians report their services?

Key Elements

Consider the basic billing principles of discharge services: what, who, and when.

Hospital discharge day management codes are used to report the physician’s total duration of time spent preparing the patient for discharge. These codes include, as appropriate:

- Final examination of the patient;

- Discussion of the hospital stay, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous;

- Instructions for continuing care to all relevant caregivers; and

- Preparation of discharge records, prescriptions, and referral forms.1

Hospitalists should report one discharge code per hospitalization, but only when the service occurs after the initial date of admission: 99238, hospital discharge day management, 30 minutes or less; or 99239, hospital discharge day management, more than 30 minutes.1,2 Select one of the two codes, depending upon the cumulative discharge service time provided on the patient’s hospital unit/floor during a single calendar day. Do not count time for services performed outside of the patient’s unit or floor (i.e., calls to the receiving physician/facility made from the physician’s private office) or services performed after the patient physically leaves the hospital.

Physician documentation must refer to the discharge status, as well as other clinically relevant information. Don’t be misled into believing that the presence of a discharge summary alone satisfies documentation requirements. In addition to the discharge groundwork, hospitalists must physically see the patient on the day he or she reports discharge management. Discharge summaries are not always useful in noting the physician’s required face-to-face encounter with the patient. Simply state, “Patient seen and examined by me on discharge day.”

Alternatively, hospitalists can elect to include details of a discharge day exam. Although a final exam isn’t mandatory for billing 99238-99239, it is the best justification of a face-to-face encounter on discharge day. Documentation of the time is required when reporting 99239 (e.g., discharge time >30 minutes). Time isn’t typically included in a discharge summary, and upon post-payment payor review, a claim involving 99239 without documented time in the patient’s medical record might result in either a service reduction to the lower level of care (99238) or a request for payment refund.3 Physicians can document all necessary details in the formal summary or a progress note.

Transfers of Care

The admitting physician or group is responsible for performing discharge services unless a formal transfer of care occurs, such as the patient’s transfer from the ICU to the standard medical floor as the patient’s condition improves. Without this transfer of care, comanaging physicians should merely report subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233) for the final patient encounter. An example of this is surgical comanagement: If a surgeon is identified as the attending of record, they are responsible for postoperative management of the patient, including discharge services.4,5 Providers in a different group or specialty report 99231-99233 for their medically necessary care.

As with all other time-based services, only the billing provider’s time counts. Discharge-related services performed by residents, students, or ancillary staff (i.e., RNs) do not count toward the physician’s discharge service time. Report the date of the physician’s actual discharge visit even if the patient leaves the facility on a different calendar date—for example, if a patient leaves the next day due to availability of the receiving facility.

Pronouncement of Death

Physicians might not realize that they can report discharge day management codes for pronouncement of death.7 Only the hospitalist who performs the pronouncement is allowed to report this service on the date pronouncement occurred, even if the paperwork is delayed to a subsequent date. Completion of the death certificate alone is not sufficient for billing. Hospitalists must “examine” the patient, thus satisfying the “face to face” visit requirement.

Additional services (e.g., speaking with family members, speaking with healthcare providers, filling out the necessary documentation) count toward the cumulative discharge service time, if performed on the patient’s unit or floor. Document the cumulative time when reporting 99239.

Back to the Case

Typical billing and payment rules mandate the reporting of only one E/M service per specialty, per patient, per day. One of the few exceptions involves reporting a hospital discharge code (99238-99239) with initial nursing facility care (99304-99306). Either the same physician or different physicians from the same group and specialty can report the hospital discharge and the nursing facility admission on the same day. When the same physician or group discharges the patient from any other location (e.g., observation unit) on the same day, report only one service: either the observation discharge (99217) or the initial nursing facility care (99304-99306).

When the same physician or group discharges a patient from the hospital and admits the patient to a facility other than a nursing facility on the same day, report only one service: either the hospital discharge (99228-99239) or the admission care (e.g., long-term acute-care hospital: 99221-99223). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2010.

- Highmark Medicare Services Provider Bulletins: Hospital Discharge Day Management Codes 99238 and 99239. Highmark Medicare Services Web site. Available at: www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/bulletins/partb/news02212008a.html. Accessed March 4, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.1A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.3B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site, Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.2E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1d. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Reporting inpatient hospital evaluation and management (E/M) services that could be described by current procedural terminology (CPT) consultation codes. Cigna Government Services Web site. Available at: www.cignagovernmentservices.com/partb/pubs/news/2010/0210/cope11694.html. Accessed March 5, 2010.

Discharge day management services (99238-99239) seem unlikely to cause confusion in the physician community; however, continued requests for documentation involving these CPT codes prove the opposite.

Here’s an example of how a billing error might be made for discharge day management services. A patient with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease is stable for discharge. The patient is being transferred to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Dr. Aardsma prepares the patient for hospital discharge, and Dr. Broxton admits the patient to the SNF later that day. Dr. Aardsma and Dr. Broxton are members of the same group practice, with the same specialty designation. Can both physicians report their services?

Key Elements

Consider the basic billing principles of discharge services: what, who, and when.

Hospital discharge day management codes are used to report the physician’s total duration of time spent preparing the patient for discharge. These codes include, as appropriate:

- Final examination of the patient;

- Discussion of the hospital stay, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous;

- Instructions for continuing care to all relevant caregivers; and

- Preparation of discharge records, prescriptions, and referral forms.1

Hospitalists should report one discharge code per hospitalization, but only when the service occurs after the initial date of admission: 99238, hospital discharge day management, 30 minutes or less; or 99239, hospital discharge day management, more than 30 minutes.1,2 Select one of the two codes, depending upon the cumulative discharge service time provided on the patient’s hospital unit/floor during a single calendar day. Do not count time for services performed outside of the patient’s unit or floor (i.e., calls to the receiving physician/facility made from the physician’s private office) or services performed after the patient physically leaves the hospital.

Physician documentation must refer to the discharge status, as well as other clinically relevant information. Don’t be misled into believing that the presence of a discharge summary alone satisfies documentation requirements. In addition to the discharge groundwork, hospitalists must physically see the patient on the day he or she reports discharge management. Discharge summaries are not always useful in noting the physician’s required face-to-face encounter with the patient. Simply state, “Patient seen and examined by me on discharge day.”

Alternatively, hospitalists can elect to include details of a discharge day exam. Although a final exam isn’t mandatory for billing 99238-99239, it is the best justification of a face-to-face encounter on discharge day. Documentation of the time is required when reporting 99239 (e.g., discharge time >30 minutes). Time isn’t typically included in a discharge summary, and upon post-payment payor review, a claim involving 99239 without documented time in the patient’s medical record might result in either a service reduction to the lower level of care (99238) or a request for payment refund.3 Physicians can document all necessary details in the formal summary or a progress note.

Transfers of Care

The admitting physician or group is responsible for performing discharge services unless a formal transfer of care occurs, such as the patient’s transfer from the ICU to the standard medical floor as the patient’s condition improves. Without this transfer of care, comanaging physicians should merely report subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233) for the final patient encounter. An example of this is surgical comanagement: If a surgeon is identified as the attending of record, they are responsible for postoperative management of the patient, including discharge services.4,5 Providers in a different group or specialty report 99231-99233 for their medically necessary care.

As with all other time-based services, only the billing provider’s time counts. Discharge-related services performed by residents, students, or ancillary staff (i.e., RNs) do not count toward the physician’s discharge service time. Report the date of the physician’s actual discharge visit even if the patient leaves the facility on a different calendar date—for example, if a patient leaves the next day due to availability of the receiving facility.

Pronouncement of Death

Physicians might not realize that they can report discharge day management codes for pronouncement of death.7 Only the hospitalist who performs the pronouncement is allowed to report this service on the date pronouncement occurred, even if the paperwork is delayed to a subsequent date. Completion of the death certificate alone is not sufficient for billing. Hospitalists must “examine” the patient, thus satisfying the “face to face” visit requirement.

Additional services (e.g., speaking with family members, speaking with healthcare providers, filling out the necessary documentation) count toward the cumulative discharge service time, if performed on the patient’s unit or floor. Document the cumulative time when reporting 99239.

Back to the Case

Typical billing and payment rules mandate the reporting of only one E/M service per specialty, per patient, per day. One of the few exceptions involves reporting a hospital discharge code (99238-99239) with initial nursing facility care (99304-99306). Either the same physician or different physicians from the same group and specialty can report the hospital discharge and the nursing facility admission on the same day. When the same physician or group discharges the patient from any other location (e.g., observation unit) on the same day, report only one service: either the observation discharge (99217) or the initial nursing facility care (99304-99306).

When the same physician or group discharges a patient from the hospital and admits the patient to a facility other than a nursing facility on the same day, report only one service: either the hospital discharge (99228-99239) or the admission care (e.g., long-term acute-care hospital: 99221-99223). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2010.

- Highmark Medicare Services Provider Bulletins: Hospital Discharge Day Management Codes 99238 and 99239. Highmark Medicare Services Web site. Available at: www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/bulletins/partb/news02212008a.html. Accessed March 4, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.1A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40.3B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site, Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.2E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.1d. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- Reporting inpatient hospital evaluation and management (E/M) services that could be described by current procedural terminology (CPT) consultation codes. Cigna Government Services Web site. Available at: www.cignagovernmentservices.com/partb/pubs/news/2010/0210/cope11694.html. Accessed March 5, 2010.

Admit Documentation

In light of the recent elimination of consultation codes from the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, physicians of all specialties are being asked to report initial hospital care services (99221-99223) for their first encounter with a patient.1 This leaves hospitalists with questions about the billing and financial implications of reporting admissions services.

Here’s a typical scenario: Dr. A admits a Medicare patient to the hospital from the ED for hyperglycemia and dehydration in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes. He performs and documents an initial hospital-care service on day one of the admission. On day two, another hospitalist, Dr. B, who works in the same HM group, sees the patient for the first time. What should each of the physicians report for their first encounter with the patient?

Each hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and their role in the case. Remember, only one physician is named “attending of record” or “admitting physician.”

When billing during the course of the hospitalization, consider all physicians of the same specialty in the same provider group as the “admitting physician/group.”

Admissions Service

On day one, Dr. A admits the patient. He performs and documents a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity. The documentation corresponds to the highest initial admission service, 99223. Given the recent Medicare billing changes, the attending of record is required to append modifier “AI” (principal physician of record) to the admission service (e.g., 99223-AI).

The purpose of this modifier is “to identify the physician who oversees the patient’s care from all other physicians who may be furnishing specialty care.”2 This modifier has no financial implications. It does not increase or decrease the payment associated with the reported visit level (i.e., 99223 is reimbursed at a national rate of approximately $190, with or without modifier AI).

Initial Encounter by Team Members

As previously stated, the elimination of consultation services requires physicians to report their initial hospital encounter with an initial hospital-care code (i.e., 99221-99223). However, Medicare states that “physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician.”3 This means followup services performed on days subsequent to a group member’s initial admission service must be reported with subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233). Therefore, in the scenario above, Dr. B is obligated to report the appropriate subsequent hospital-care code for his patient encounter on day two.

Incomplete Documentation

Initial hospital-care services (99221-99223) require the physician to obtain, perform, and document the necessary elements of history, physical exam, and medical decision-making in support of the code reported on the claim. There are occasions when the physician’s documentation does not support the lowest code (i.e., 99221). A reasonable approach is to report the service with an unlisted E&M code (99499). “Unlisted” codes do not have a payor-recognized code description or fee. When reporting an unlisted code, the biller must manually enter a charge description (e.g., expanded problem-focused admissions service) and a fee. A payor-prompted request for documentation is likely before payment is made.

Some payors have more specific references to the situation and allow for options. Two options exist for coding services that do not meet the work and/or medical necessity requirements of 99221-99223: report an unlisted E&M service (99499); or report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) that appropriately reflects physician work and medical necessity for the service, and avoids mandatory medical record submission and manual medical review.4

In fact, Medicare Administrator Contractor TrailBlazer Health’s Web site (www.trailblazerhealth.com) offers guidance to physicians who are unsure if subsequent hospital care is an appropriate choice for this dilemma: “TrailBlazer recognizes provider reluctance to miscode initial hospital care as subsequent hospital care. However, doing so is preferable in that it allows Medicare to process and pay the claims much more efficiently. For those concerned about miscoding these services, please understand that TrailBlazer will not find fault with providers who choose this option when records appropriately demonstrate the work and medical necessity of the subsequent code chosen.”4 TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- CMS announces payment, policy changes for physicians services to Medicare beneficiaries in 2010. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/ press/release.asp?Counter=3539&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=1%2C+2%2C+3%2C+4%2C+5&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=&cboOrder=date. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Revisions to Consultation Services Payment Policy. Medicare Learning Network Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/ MM6740.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Update-evaluation and management services formerly coded as consultations. Trailblazer Health Enterprises Web site. Available at: www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/Notices.aspx?DomainID=1. Accessed Jan. 17, 2010.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2009;14-15.

In light of the recent elimination of consultation codes from the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, physicians of all specialties are being asked to report initial hospital care services (99221-99223) for their first encounter with a patient.1 This leaves hospitalists with questions about the billing and financial implications of reporting admissions services.

Here’s a typical scenario: Dr. A admits a Medicare patient to the hospital from the ED for hyperglycemia and dehydration in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes. He performs and documents an initial hospital-care service on day one of the admission. On day two, another hospitalist, Dr. B, who works in the same HM group, sees the patient for the first time. What should each of the physicians report for their first encounter with the patient?

Each hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and their role in the case. Remember, only one physician is named “attending of record” or “admitting physician.”

When billing during the course of the hospitalization, consider all physicians of the same specialty in the same provider group as the “admitting physician/group.”

Admissions Service

On day one, Dr. A admits the patient. He performs and documents a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity. The documentation corresponds to the highest initial admission service, 99223. Given the recent Medicare billing changes, the attending of record is required to append modifier “AI” (principal physician of record) to the admission service (e.g., 99223-AI).

The purpose of this modifier is “to identify the physician who oversees the patient’s care from all other physicians who may be furnishing specialty care.”2 This modifier has no financial implications. It does not increase or decrease the payment associated with the reported visit level (i.e., 99223 is reimbursed at a national rate of approximately $190, with or without modifier AI).

Initial Encounter by Team Members

As previously stated, the elimination of consultation services requires physicians to report their initial hospital encounter with an initial hospital-care code (i.e., 99221-99223). However, Medicare states that “physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician.”3 This means followup services performed on days subsequent to a group member’s initial admission service must be reported with subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233). Therefore, in the scenario above, Dr. B is obligated to report the appropriate subsequent hospital-care code for his patient encounter on day two.

Incomplete Documentation

Initial hospital-care services (99221-99223) require the physician to obtain, perform, and document the necessary elements of history, physical exam, and medical decision-making in support of the code reported on the claim. There are occasions when the physician’s documentation does not support the lowest code (i.e., 99221). A reasonable approach is to report the service with an unlisted E&M code (99499). “Unlisted” codes do not have a payor-recognized code description or fee. When reporting an unlisted code, the biller must manually enter a charge description (e.g., expanded problem-focused admissions service) and a fee. A payor-prompted request for documentation is likely before payment is made.

Some payors have more specific references to the situation and allow for options. Two options exist for coding services that do not meet the work and/or medical necessity requirements of 99221-99223: report an unlisted E&M service (99499); or report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) that appropriately reflects physician work and medical necessity for the service, and avoids mandatory medical record submission and manual medical review.4

In fact, Medicare Administrator Contractor TrailBlazer Health’s Web site (www.trailblazerhealth.com) offers guidance to physicians who are unsure if subsequent hospital care is an appropriate choice for this dilemma: “TrailBlazer recognizes provider reluctance to miscode initial hospital care as subsequent hospital care. However, doing so is preferable in that it allows Medicare to process and pay the claims much more efficiently. For those concerned about miscoding these services, please understand that TrailBlazer will not find fault with providers who choose this option when records appropriately demonstrate the work and medical necessity of the subsequent code chosen.”4 TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- CMS announces payment, policy changes for physicians services to Medicare beneficiaries in 2010. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/ press/release.asp?Counter=3539&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=1%2C+2%2C+3%2C+4%2C+5&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=&cboOrder=date. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Revisions to Consultation Services Payment Policy. Medicare Learning Network Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/ MM6740.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Update-evaluation and management services formerly coded as consultations. Trailblazer Health Enterprises Web site. Available at: www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/Notices.aspx?DomainID=1. Accessed Jan. 17, 2010.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2009;14-15.

In light of the recent elimination of consultation codes from the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, physicians of all specialties are being asked to report initial hospital care services (99221-99223) for their first encounter with a patient.1 This leaves hospitalists with questions about the billing and financial implications of reporting admissions services.

Here’s a typical scenario: Dr. A admits a Medicare patient to the hospital from the ED for hyperglycemia and dehydration in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes. He performs and documents an initial hospital-care service on day one of the admission. On day two, another hospitalist, Dr. B, who works in the same HM group, sees the patient for the first time. What should each of the physicians report for their first encounter with the patient?

Each hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and their role in the case. Remember, only one physician is named “attending of record” or “admitting physician.”

When billing during the course of the hospitalization, consider all physicians of the same specialty in the same provider group as the “admitting physician/group.”

Admissions Service

On day one, Dr. A admits the patient. He performs and documents a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity. The documentation corresponds to the highest initial admission service, 99223. Given the recent Medicare billing changes, the attending of record is required to append modifier “AI” (principal physician of record) to the admission service (e.g., 99223-AI).

The purpose of this modifier is “to identify the physician who oversees the patient’s care from all other physicians who may be furnishing specialty care.”2 This modifier has no financial implications. It does not increase or decrease the payment associated with the reported visit level (i.e., 99223 is reimbursed at a national rate of approximately $190, with or without modifier AI).

Initial Encounter by Team Members

As previously stated, the elimination of consultation services requires physicians to report their initial hospital encounter with an initial hospital-care code (i.e., 99221-99223). However, Medicare states that “physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician.”3 This means followup services performed on days subsequent to a group member’s initial admission service must be reported with subsequent hospital-care codes (99231-99233). Therefore, in the scenario above, Dr. B is obligated to report the appropriate subsequent hospital-care code for his patient encounter on day two.

Incomplete Documentation

Initial hospital-care services (99221-99223) require the physician to obtain, perform, and document the necessary elements of history, physical exam, and medical decision-making in support of the code reported on the claim. There are occasions when the physician’s documentation does not support the lowest code (i.e., 99221). A reasonable approach is to report the service with an unlisted E&M code (99499). “Unlisted” codes do not have a payor-recognized code description or fee. When reporting an unlisted code, the biller must manually enter a charge description (e.g., expanded problem-focused admissions service) and a fee. A payor-prompted request for documentation is likely before payment is made.

Some payors have more specific references to the situation and allow for options. Two options exist for coding services that do not meet the work and/or medical necessity requirements of 99221-99223: report an unlisted E&M service (99499); or report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) that appropriately reflects physician work and medical necessity for the service, and avoids mandatory medical record submission and manual medical review.4

In fact, Medicare Administrator Contractor TrailBlazer Health’s Web site (www.trailblazerhealth.com) offers guidance to physicians who are unsure if subsequent hospital care is an appropriate choice for this dilemma: “TrailBlazer recognizes provider reluctance to miscode initial hospital care as subsequent hospital care. However, doing so is preferable in that it allows Medicare to process and pay the claims much more efficiently. For those concerned about miscoding these services, please understand that TrailBlazer will not find fault with providers who choose this option when records appropriately demonstrate the work and medical necessity of the subsequent code chosen.”4 TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- CMS announces payment, policy changes for physicians services to Medicare beneficiaries in 2010. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/ press/release.asp?Counter=3539&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=1%2C+2%2C+3%2C+4%2C+5&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=&cboOrder=date. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Revisions to Consultation Services Payment Policy. Medicare Learning Network Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/ MM6740.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2010.

- Update-evaluation and management services formerly coded as consultations. Trailblazer Health Enterprises Web site. Available at: www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/Notices.aspx?DomainID=1. Accessed Jan. 17, 2010.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2009;14-15.

Consultation Elimination

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario