User login

CDC panel updates info on rare side effect after J&J vaccine

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Disturbing number of hospital workers still unvaccinated

Tim Oswalt had been in a Fort Worth, Texas, hospital for over a month, receiving treatment for a grapefruit-sized tumor in his chest that was pressing on his heart and lungs. It turned out to be stage 3 non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Then one day in January, he was moved from his semi-private room to an isolated one with special ventilation. The staff explained he had been infected by the virus that was once again surging in many areas of the country, including Texas.

“How the hell did I catch COVID?” he asked the staff, who now approached him in full moon-suit personal protective equipment (PPE).

The hospital was locked down, and Mr. Oswalt hadn’t had any visitors in weeks. Neither of his two roommates tested positive. He’d been tested for COVID several times over the course of his nearly 5-week stay and was always negative.

“‘Well, you know, it’s easy to [catch it] in a hospital,’” Mr. Oswalt said he was told by hospital staff. “‘We’re having a bad outbreak. So you were just exposed somehow.’”

Officials at John Peter Smith Hospital, where Mr. Oswalt was treated, said they are puzzled by his case. According to their infection prevention team, none of his caregivers tested positive for COVID-19, nor did Mr. Oswalt share space with any other COVID-positive patients. And yet, local media reported a surge in cases among JPS hospital staff in December.

“Infection of any kind is a constant battle within hospitals and one that we all take seriously,” said Rob Stephenson, MD, chief quality officer at JPS Health Network. “Anyone in a vulnerable health condition at the height of the pandemic would have been at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 inside – or even more so, outside – the hospital.”

Mr. Oswalt was diagnosed with COVID in early January. JPS Hospital began vaccinating its health care workers about 2 weeks earlier, so there had not yet been enough time for any of them to develop full protection against catching or spreading the virus.

Today, the hospital said 74% of its staff – 5,300 of 7,200 workers – are now vaccinated.

against the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Refusing vaccinations

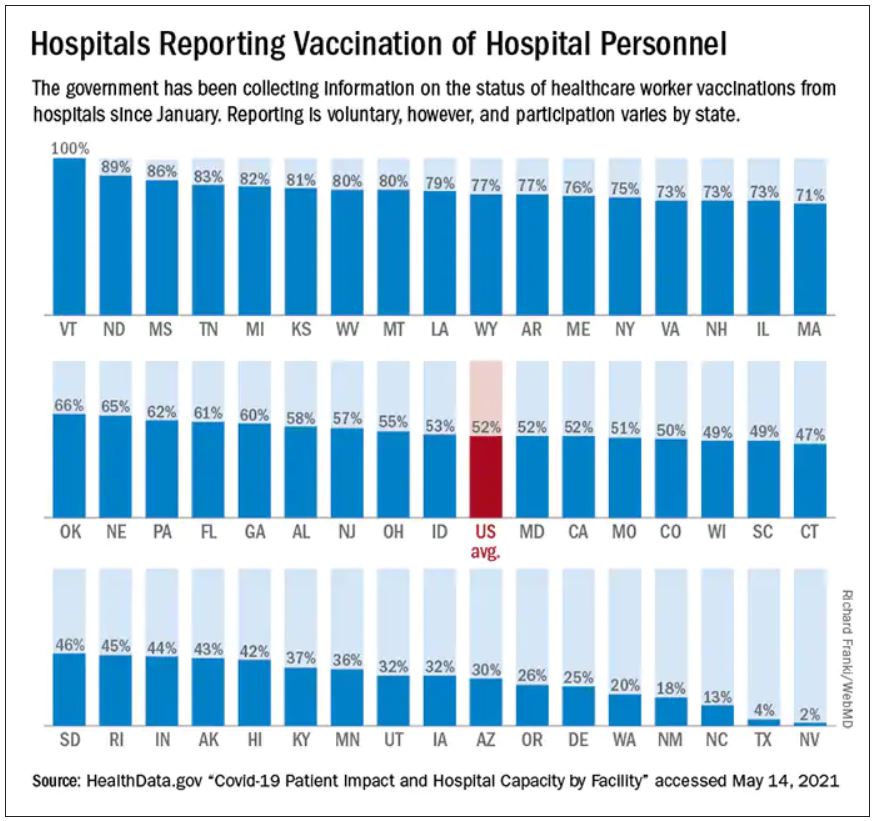

In fact, nationwide, 1 in 4 hospital workers who have direct contact with patients had not yet received a single dose of a COVID vaccine by the end of May, according to a WebMD and Medscape Medical News analysis of data collected by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from 2,500 hospitals across the United States.

Among the nation’s 50 largest hospitals, the percentage of unvaccinated health care workers appears to be even larger, about 1 in 3. Vaccination rates range from a high of 99% at Houston Methodist Hospital, which was the first in the nation to mandate the shots for its workers, to a low between 30% and 40% at some hospitals in Florida.

Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center in Houston has 1,180 beds and sits less than half a mile from Houston Methodist Hospital. But in terms of worker vaccinations, it is farther away.

Memorial Hermann reported to HHS that about 32% of its 28,000 workers haven’t been inoculated. The hospital’s PR office contests that figure, putting it closer to 25% unvaccinated across their health system. The hospital said it is boosting participation by offering a $300 “shot of hope” bonus to workers who start their vaccination series by the end of June.

Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla., reported to HHS that 63% of its health care personnel are still unvaccinated. The hospital did not return a call to verify that number.

To boost vaccination rates, more hospitals are starting to require the shots, after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission gave its green light to mandates in May.

“It’s a real problem that you have such high levels of unvaccinated individuals in hospitals,” said Lawrence Gostin, JD, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, Washington.

“We have to protect our health workforce, and we have to protect our patients. Hospitals should be the safest places in the country, and the only way to make them safe is to have a fully vaccinated workforce,” Mr. Gostin said.

Is the data misleading?

The HHS system designed to amass hospital data was set up quickly, to respond to an emergency. For that reason, experts say the information hasn’t been as carefully collected or vetted as it normally would have been. Some hospitals may have misunderstood how to report their vaccination numbers.

In addition, reporting data on worker vaccinations is voluntary. Only about half of hospitals have chosen to share their numbers. In other cases, like Texas, states have blocked the public release of these statistics.

AdventHealth Orlando, a 1,300-bed hospital in Florida, reported to HHS that 56% of its staff have not started their shots. But spokesman Jeff Grainger said the figures probably overstate the number of unvaccinated workers because the hospital doesn’t always know when people get vaccinated outside of its campus, at a local pharmacy, for example.

For those reasons, the picture of health care worker vaccinations across the country is incomplete.

Where hospitals fall behind

Even if the data are flawed, the vaccination rates from hospitals mirror the general population. A May Gallup poll, for example, found 24% of Americans said they definitely won’t get the vaccine. Another 12% say they plan to get it but are waiting.

The data also align with recent studies. A review of 35 studies by researchers at New Mexico State University that assessed hesitancy in more than 76,000 health care workers around the world found about 23% of them were reluctant to get the shots.

An ongoing monthly survey of more than 1.9 million U.S. Facebook users led by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh recently looked at vaccine hesitancy by occupation. It revealed a spectrum of hesitancy among health care workers corresponding to income and education, ranging from a low of 9% among pharmacists to highs of 20%-23% among nursing aides and emergency medical technicians. About 12% of registered nurses and doctors admitted to being hesitant to get a shot.

“Health care workers are not monolithic,” said study author Jagdish Khubchandani, professor of public health sciences at New Mexico State.

“There’s a big divide between males, doctoral degree holders, older people and the younger low-income, low-education frontline, female, health care workers. They are the most hesitant,” he said. Support staff typically outnumbers doctors at hospitals about 3 to 1.

“There is outreach work to be done there,” said Robin Mejia, PhD, director of the Statistics and Human Rights Program at Carnegie Mellon, who is leading the study on Facebook’s survey data. “These are also high-contact professions. These are people who are seeing patients on a regular basis.”

That’s why, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was planning the national vaccine rollout, they prioritized health care workers for the initially scarce first doses. The intent was to protect vulnerable workers and their patients who are at high risk of infection. But the CDC had another reason for putting health care workers first: After they were safely vaccinated, the hope was that they would encourage wary patients to do the same.

Hospitals were supposed to be hubs of education to help build trust within less confident communities. But not all hospitals have risen to that challenge.

Political affiliation seems to be one contributing factor in vaccine hesitancy. Take for example Calhoun, Ga., the seat of Gordon County, where residents voted for Donald Trump over Joe Biden by a 67-point margin in the 2020 general election. Studies have found that Republicans are more likely to decline vaccines than Democrats.

People who live in rural areas are less likely to be vaccinated than those who live in cities, and that’s true in Gordon County too. Vaccinations are lagging in this northwest corner of Georgia where factory jobs in chicken processing plants and carpet manufacturing energize the local economy. Just 24% of Gordon County residents are fully vaccinated, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

At AdventHealth Gordon, a 112-bed hospital in Calhoun, just 35% of the 1,723 workers that serve the hospital are at least partially vaccinated, according to data reported to HHS.

‘I am not vaccinated’

One reason some hospital staff say they are resisting COVID vaccination is because it’s so new and not yet fully approved by the FDA.

“I am not vaccinated,” said a social services worker for AdventHealth Gordon who asked that her name not be used because she was unauthorized to speak to this news organization and Georgia Health News (who collaborated on this project). “I just have not felt the need to do that at this time.”

The woman said she doesn’t have a problem with vaccines. She gets the flu shot every year. “I’ve been vaccinated all my life,” she said. But she doesn’t view COVID-19 vaccination in the same way.

“I want to see more testing done,” she said. “It took a long time to get a flu vaccine, and we made a COVID vaccine in 6 months. I want to know, before I start putting something into my body, that the testing is done.”

Staff at her hospital were given the option to be vaccinated or wear a mask. She chose the mask.

Many of her coworkers share her feelings, she said.

Mask expert Linsey Marr, PhD, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, Va., said N95 masks and vaccines are both highly effective, but the protection from the vaccine is superior because it is continuous.

“It’s hard to wear an N95 at all times. You have to take it off to eat, for example, in a break room in a hospital. I should point out that you can be exposed to the virus in other buildings besides a hospital – restaurants, stores, people’s homes – and because someone can be infected without symptoms, you could easily be around an infected person without knowing it,” she said.

Eventually, staff at AdventHealth Gordon may get a stronger nudge to get the shots. Chief Medical Officer Joseph Joyave, MD, said AdventHealth asks workers to get flu vaccines or provide the hospital with a reason why they won’t. He expects a similar policy will be adopted for COVID vaccines once they are fully licensed by the FDA.

In the meantime, he does not believe that the hospital is putting patients at risk with its low vaccination rate. “We continue to use PPE, masking in all clinical areas, and continue to screen daily all employees and visitors,” he said.

AdventHealth, the 12th largest hospital system in the nation with 49 hospitals, has at least 20 hospitals with vaccination rates lower than 50%, according to HHS data.

Other hospital systems have approached hesitation around the COVID vaccines differently.

When infectious disease experts at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville realized early on that many of their workers felt unsure about the vaccines, they set out to provide a wealth of information.

“There was a lot of hesitancy and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious disease at Vanderbilt. So the infectious disease division put together a multifaceted program including Q&As, educational sessions, and one-on-one visits with employees “from the custodians all the way up to the C-Suite,” he said.

Today, HHS data shows the hospital is 83% vaccinated. Dr. Schaffner thinks the true number is probably higher, about 90%. “We’re very pleased with that,” he said.

In his experience with flu vaccinations, it was extremely difficult in the first year to get workers to take flu shots. The second year it was easier. By the third year it was humdrum, he said, because it had become a cultural norm.

Dr. Schaffner expects winning people over to the COVID vaccines will follow a similar course, but “we’re not there yet,” he said.

Protecting patients and caregivers

There is no question that health care workers carried a heavy load through the worst months of the pandemic. Many of them worked to the point of exhaustion and burnout. Some were the only conduits between isolated patients and their families, holding hands and mobile phones so distanced loved ones could video chat. Many were left inadequately protected because of shortages of masks, gowns, gloves, and other gear.

An investigation by Kaiser Health News and The Guardian recently revealed that more than 3,600 health care workers died in COVID’s first year in the United States.

Vaccination of health care workers is important to protect these frontline workers and their families who will continue to be at risk of coming into contact with the infection, even as the number of cases falls.

Hesitancy in health care is also dangerous because these clinicians and allied health workers – who may not show any symptoms – can also carry the virus to someone who wouldn’t survive an infection, including patients with organ transplants, those with autoimmune diseases, premature infants, and the elderly.

It is not known how often patients in the United States are infected with COVID in health care settings, but case reports reveal that hospitals are still experiencing outbreaks.

On June 1, Northern Lights A.R. Gould Hospital in Presque Isle, Maine, announced a COVID outbreak on its medical-surgical unit. As of June 22, 13 residents and staff have caught the virus, according to the Maine Centers for Disease Control, which is investigating. Four of the first five staff members to test positive had not been fully vaccinated.

According to HHS data, about 20% of the health care workers at that hospital are still unvaccinated.

Oregon Health & Science University experienced a COVID outbreak connected to the hospital’s cardiovascular care unit from April to mid-May of this year. According to hospital spokesperson Tracy Brawley, a patient visitor brought the infection to campus, where it ultimately spread to 14 others, including “patients, visitors, employees, and learners.”

In a written statement, the hospital said “nearly all” health care workers who tested positive were previously vaccinated and experienced no symptoms or only minor ones. The hospital said it hasn’t identified any onward transmission from health care workers to patients, and also stated: “It is not yet understood how transmission may have occurred between patients, visitors, and health care workers.”

In March, an unvaccinated health care worker in Kentucky carried a SARS-CoV-2 variant back to the nursing home where the person worked. Some 90% of the residents were fully vaccinated. Ultimately, 26 patients were infected; 18 of them were fully vaccinated. And 20 health care workers, four of whom were vaccinated, were infected.

Vaccines slowed the virus down and made infections less severe, but in this fragile population, they couldn’t stop it completely. One resident, who had survived a bout of COVID almost a year earlier, died. According to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47% of the workers in that facility were unvaccinated.

In the United Kingdom, statistics collected through that country’s National Health Service also suggest a heavy toll. More than 32,300 patients caught COVID in English hospitals since March 2020. Up to 8,700 of them died, according to a recent analysis by The Guardian. The U.K. government recently made COVID vaccinations mandatory for health care workers.

COVID delays cancer care

When Mr. Oswalt, the Fort Worth, Texas man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, contracted COVID-19, the virus took down his kidneys first. Toxins were building up in his blood, so doctors prescribed dialysis to support his body and buy his kidneys time to heal.

He was in one of these dialysis treatments when his lungs succumbed.

“Look, I can’t breathe,” he told the nurse who was supervising his treatment. The nurse gestured to an oxygen tank already hanging by his side, and said, “You should be OK.”

But he wasn’t.

“I can’t breathe,” Mr. Oswalt said again. Then the air hunger hit. Mr. Oswalt began gasping and couldn’t stop. Today, his voice breaks when he describes this moment. “A lot of it becomes a blur.”

When Mr. Oswalt, 61, regained consciousness, he was hooked up to a ventilator to ease his breathing.

For days, Mr. Oswalt clung to the edge of life. His wife, Molly, who wasn’t allowed to see him in the hospital, got a call that he might not make it through the night. She made frantic phone calls to her brother and sister and prayed.

Mr. Oswalt was on a ventilator for about a week. His kidneys and lungs healed enough so that he could restart his chemotherapy. He was eventually discharged home on January 22.

The last time he was scanned, the large tumor in his chest had shrunk from the size of a grapefruit to the size of a dime.

But having COVID on top of cancer has had a devastating effect on his life. Before he got sick, Molly said, he couldn’t stay still. He was busy all the time. After spending months in the hospital, his energy was depleted. He couldn’t keep his swimming pool installation business going.

He and Molly had to give up their house in Fort Worth and move in with family in Amarillo. He has had to pause his cancer treatments while doctors wait for his kidneys to heal. Relatives have been raising money on GoFundMe to pay their bills.

Months after moving across the state to Amarillo and hoping for better days, Tim said he got good news this week: He no longer needs dialysis. A new round of tests found no signs of cancer. His white blood cell count is back to normal. His lymph nodes are no longer swollen.

He goes back for another scan in a few weeks, but the doctor told him she isn’t going to recommend any further chemo at this point.

“It was shocking, to tell you the truth. It still is. When I talk about it, I get kind of emotional” about his recovery, he said.

Tim said he was really dreading more chemotherapy. His hair has just started growing back. He can finally taste food again. He wasn’t ready to face more side effects from the treatments, or the COVID – he no longer knows exactly which diagnosis led to his most debilitating symptoms.

He said his ordeal has left him with no patience for health care workers who don’t think they need to be vaccinated.

The way he sees it, it’s no different than the electrical training he had to get before he could wire the lights and pumps in a swimming pool.

“You know, if I don’t certify and keep my license, I can’t work on anything electrical. So, if I’ve made the choice not to go down and take the test and get a license, then I made the choice not to work on electrical stuff,” he said.

He supports the growing number of hospitals that have made vaccination mandatory for their workers.

“They don’t let electricians put people at risk. And they shouldn’t let health care workers for sure,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tim Oswalt had been in a Fort Worth, Texas, hospital for over a month, receiving treatment for a grapefruit-sized tumor in his chest that was pressing on his heart and lungs. It turned out to be stage 3 non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Then one day in January, he was moved from his semi-private room to an isolated one with special ventilation. The staff explained he had been infected by the virus that was once again surging in many areas of the country, including Texas.

“How the hell did I catch COVID?” he asked the staff, who now approached him in full moon-suit personal protective equipment (PPE).

The hospital was locked down, and Mr. Oswalt hadn’t had any visitors in weeks. Neither of his two roommates tested positive. He’d been tested for COVID several times over the course of his nearly 5-week stay and was always negative.

“‘Well, you know, it’s easy to [catch it] in a hospital,’” Mr. Oswalt said he was told by hospital staff. “‘We’re having a bad outbreak. So you were just exposed somehow.’”

Officials at John Peter Smith Hospital, where Mr. Oswalt was treated, said they are puzzled by his case. According to their infection prevention team, none of his caregivers tested positive for COVID-19, nor did Mr. Oswalt share space with any other COVID-positive patients. And yet, local media reported a surge in cases among JPS hospital staff in December.

“Infection of any kind is a constant battle within hospitals and one that we all take seriously,” said Rob Stephenson, MD, chief quality officer at JPS Health Network. “Anyone in a vulnerable health condition at the height of the pandemic would have been at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 inside – or even more so, outside – the hospital.”

Mr. Oswalt was diagnosed with COVID in early January. JPS Hospital began vaccinating its health care workers about 2 weeks earlier, so there had not yet been enough time for any of them to develop full protection against catching or spreading the virus.

Today, the hospital said 74% of its staff – 5,300 of 7,200 workers – are now vaccinated.

against the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Refusing vaccinations

In fact, nationwide, 1 in 4 hospital workers who have direct contact with patients had not yet received a single dose of a COVID vaccine by the end of May, according to a WebMD and Medscape Medical News analysis of data collected by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from 2,500 hospitals across the United States.

Among the nation’s 50 largest hospitals, the percentage of unvaccinated health care workers appears to be even larger, about 1 in 3. Vaccination rates range from a high of 99% at Houston Methodist Hospital, which was the first in the nation to mandate the shots for its workers, to a low between 30% and 40% at some hospitals in Florida.

Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center in Houston has 1,180 beds and sits less than half a mile from Houston Methodist Hospital. But in terms of worker vaccinations, it is farther away.

Memorial Hermann reported to HHS that about 32% of its 28,000 workers haven’t been inoculated. The hospital’s PR office contests that figure, putting it closer to 25% unvaccinated across their health system. The hospital said it is boosting participation by offering a $300 “shot of hope” bonus to workers who start their vaccination series by the end of June.

Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla., reported to HHS that 63% of its health care personnel are still unvaccinated. The hospital did not return a call to verify that number.

To boost vaccination rates, more hospitals are starting to require the shots, after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission gave its green light to mandates in May.

“It’s a real problem that you have such high levels of unvaccinated individuals in hospitals,” said Lawrence Gostin, JD, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, Washington.

“We have to protect our health workforce, and we have to protect our patients. Hospitals should be the safest places in the country, and the only way to make them safe is to have a fully vaccinated workforce,” Mr. Gostin said.

Is the data misleading?

The HHS system designed to amass hospital data was set up quickly, to respond to an emergency. For that reason, experts say the information hasn’t been as carefully collected or vetted as it normally would have been. Some hospitals may have misunderstood how to report their vaccination numbers.

In addition, reporting data on worker vaccinations is voluntary. Only about half of hospitals have chosen to share their numbers. In other cases, like Texas, states have blocked the public release of these statistics.

AdventHealth Orlando, a 1,300-bed hospital in Florida, reported to HHS that 56% of its staff have not started their shots. But spokesman Jeff Grainger said the figures probably overstate the number of unvaccinated workers because the hospital doesn’t always know when people get vaccinated outside of its campus, at a local pharmacy, for example.

For those reasons, the picture of health care worker vaccinations across the country is incomplete.

Where hospitals fall behind

Even if the data are flawed, the vaccination rates from hospitals mirror the general population. A May Gallup poll, for example, found 24% of Americans said they definitely won’t get the vaccine. Another 12% say they plan to get it but are waiting.

The data also align with recent studies. A review of 35 studies by researchers at New Mexico State University that assessed hesitancy in more than 76,000 health care workers around the world found about 23% of them were reluctant to get the shots.

An ongoing monthly survey of more than 1.9 million U.S. Facebook users led by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh recently looked at vaccine hesitancy by occupation. It revealed a spectrum of hesitancy among health care workers corresponding to income and education, ranging from a low of 9% among pharmacists to highs of 20%-23% among nursing aides and emergency medical technicians. About 12% of registered nurses and doctors admitted to being hesitant to get a shot.

“Health care workers are not monolithic,” said study author Jagdish Khubchandani, professor of public health sciences at New Mexico State.

“There’s a big divide between males, doctoral degree holders, older people and the younger low-income, low-education frontline, female, health care workers. They are the most hesitant,” he said. Support staff typically outnumbers doctors at hospitals about 3 to 1.

“There is outreach work to be done there,” said Robin Mejia, PhD, director of the Statistics and Human Rights Program at Carnegie Mellon, who is leading the study on Facebook’s survey data. “These are also high-contact professions. These are people who are seeing patients on a regular basis.”

That’s why, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was planning the national vaccine rollout, they prioritized health care workers for the initially scarce first doses. The intent was to protect vulnerable workers and their patients who are at high risk of infection. But the CDC had another reason for putting health care workers first: After they were safely vaccinated, the hope was that they would encourage wary patients to do the same.

Hospitals were supposed to be hubs of education to help build trust within less confident communities. But not all hospitals have risen to that challenge.

Political affiliation seems to be one contributing factor in vaccine hesitancy. Take for example Calhoun, Ga., the seat of Gordon County, where residents voted for Donald Trump over Joe Biden by a 67-point margin in the 2020 general election. Studies have found that Republicans are more likely to decline vaccines than Democrats.

People who live in rural areas are less likely to be vaccinated than those who live in cities, and that’s true in Gordon County too. Vaccinations are lagging in this northwest corner of Georgia where factory jobs in chicken processing plants and carpet manufacturing energize the local economy. Just 24% of Gordon County residents are fully vaccinated, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

At AdventHealth Gordon, a 112-bed hospital in Calhoun, just 35% of the 1,723 workers that serve the hospital are at least partially vaccinated, according to data reported to HHS.

‘I am not vaccinated’

One reason some hospital staff say they are resisting COVID vaccination is because it’s so new and not yet fully approved by the FDA.

“I am not vaccinated,” said a social services worker for AdventHealth Gordon who asked that her name not be used because she was unauthorized to speak to this news organization and Georgia Health News (who collaborated on this project). “I just have not felt the need to do that at this time.”

The woman said she doesn’t have a problem with vaccines. She gets the flu shot every year. “I’ve been vaccinated all my life,” she said. But she doesn’t view COVID-19 vaccination in the same way.

“I want to see more testing done,” she said. “It took a long time to get a flu vaccine, and we made a COVID vaccine in 6 months. I want to know, before I start putting something into my body, that the testing is done.”

Staff at her hospital were given the option to be vaccinated or wear a mask. She chose the mask.

Many of her coworkers share her feelings, she said.

Mask expert Linsey Marr, PhD, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, Va., said N95 masks and vaccines are both highly effective, but the protection from the vaccine is superior because it is continuous.

“It’s hard to wear an N95 at all times. You have to take it off to eat, for example, in a break room in a hospital. I should point out that you can be exposed to the virus in other buildings besides a hospital – restaurants, stores, people’s homes – and because someone can be infected without symptoms, you could easily be around an infected person without knowing it,” she said.

Eventually, staff at AdventHealth Gordon may get a stronger nudge to get the shots. Chief Medical Officer Joseph Joyave, MD, said AdventHealth asks workers to get flu vaccines or provide the hospital with a reason why they won’t. He expects a similar policy will be adopted for COVID vaccines once they are fully licensed by the FDA.

In the meantime, he does not believe that the hospital is putting patients at risk with its low vaccination rate. “We continue to use PPE, masking in all clinical areas, and continue to screen daily all employees and visitors,” he said.

AdventHealth, the 12th largest hospital system in the nation with 49 hospitals, has at least 20 hospitals with vaccination rates lower than 50%, according to HHS data.

Other hospital systems have approached hesitation around the COVID vaccines differently.

When infectious disease experts at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville realized early on that many of their workers felt unsure about the vaccines, they set out to provide a wealth of information.

“There was a lot of hesitancy and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious disease at Vanderbilt. So the infectious disease division put together a multifaceted program including Q&As, educational sessions, and one-on-one visits with employees “from the custodians all the way up to the C-Suite,” he said.

Today, HHS data shows the hospital is 83% vaccinated. Dr. Schaffner thinks the true number is probably higher, about 90%. “We’re very pleased with that,” he said.

In his experience with flu vaccinations, it was extremely difficult in the first year to get workers to take flu shots. The second year it was easier. By the third year it was humdrum, he said, because it had become a cultural norm.

Dr. Schaffner expects winning people over to the COVID vaccines will follow a similar course, but “we’re not there yet,” he said.

Protecting patients and caregivers

There is no question that health care workers carried a heavy load through the worst months of the pandemic. Many of them worked to the point of exhaustion and burnout. Some were the only conduits between isolated patients and their families, holding hands and mobile phones so distanced loved ones could video chat. Many were left inadequately protected because of shortages of masks, gowns, gloves, and other gear.

An investigation by Kaiser Health News and The Guardian recently revealed that more than 3,600 health care workers died in COVID’s first year in the United States.

Vaccination of health care workers is important to protect these frontline workers and their families who will continue to be at risk of coming into contact with the infection, even as the number of cases falls.

Hesitancy in health care is also dangerous because these clinicians and allied health workers – who may not show any symptoms – can also carry the virus to someone who wouldn’t survive an infection, including patients with organ transplants, those with autoimmune diseases, premature infants, and the elderly.

It is not known how often patients in the United States are infected with COVID in health care settings, but case reports reveal that hospitals are still experiencing outbreaks.

On June 1, Northern Lights A.R. Gould Hospital in Presque Isle, Maine, announced a COVID outbreak on its medical-surgical unit. As of June 22, 13 residents and staff have caught the virus, according to the Maine Centers for Disease Control, which is investigating. Four of the first five staff members to test positive had not been fully vaccinated.

According to HHS data, about 20% of the health care workers at that hospital are still unvaccinated.

Oregon Health & Science University experienced a COVID outbreak connected to the hospital’s cardiovascular care unit from April to mid-May of this year. According to hospital spokesperson Tracy Brawley, a patient visitor brought the infection to campus, where it ultimately spread to 14 others, including “patients, visitors, employees, and learners.”

In a written statement, the hospital said “nearly all” health care workers who tested positive were previously vaccinated and experienced no symptoms or only minor ones. The hospital said it hasn’t identified any onward transmission from health care workers to patients, and also stated: “It is not yet understood how transmission may have occurred between patients, visitors, and health care workers.”

In March, an unvaccinated health care worker in Kentucky carried a SARS-CoV-2 variant back to the nursing home where the person worked. Some 90% of the residents were fully vaccinated. Ultimately, 26 patients were infected; 18 of them were fully vaccinated. And 20 health care workers, four of whom were vaccinated, were infected.

Vaccines slowed the virus down and made infections less severe, but in this fragile population, they couldn’t stop it completely. One resident, who had survived a bout of COVID almost a year earlier, died. According to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47% of the workers in that facility were unvaccinated.

In the United Kingdom, statistics collected through that country’s National Health Service also suggest a heavy toll. More than 32,300 patients caught COVID in English hospitals since March 2020. Up to 8,700 of them died, according to a recent analysis by The Guardian. The U.K. government recently made COVID vaccinations mandatory for health care workers.

COVID delays cancer care

When Mr. Oswalt, the Fort Worth, Texas man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, contracted COVID-19, the virus took down his kidneys first. Toxins were building up in his blood, so doctors prescribed dialysis to support his body and buy his kidneys time to heal.

He was in one of these dialysis treatments when his lungs succumbed.

“Look, I can’t breathe,” he told the nurse who was supervising his treatment. The nurse gestured to an oxygen tank already hanging by his side, and said, “You should be OK.”

But he wasn’t.

“I can’t breathe,” Mr. Oswalt said again. Then the air hunger hit. Mr. Oswalt began gasping and couldn’t stop. Today, his voice breaks when he describes this moment. “A lot of it becomes a blur.”

When Mr. Oswalt, 61, regained consciousness, he was hooked up to a ventilator to ease his breathing.

For days, Mr. Oswalt clung to the edge of life. His wife, Molly, who wasn’t allowed to see him in the hospital, got a call that he might not make it through the night. She made frantic phone calls to her brother and sister and prayed.

Mr. Oswalt was on a ventilator for about a week. His kidneys and lungs healed enough so that he could restart his chemotherapy. He was eventually discharged home on January 22.

The last time he was scanned, the large tumor in his chest had shrunk from the size of a grapefruit to the size of a dime.

But having COVID on top of cancer has had a devastating effect on his life. Before he got sick, Molly said, he couldn’t stay still. He was busy all the time. After spending months in the hospital, his energy was depleted. He couldn’t keep his swimming pool installation business going.

He and Molly had to give up their house in Fort Worth and move in with family in Amarillo. He has had to pause his cancer treatments while doctors wait for his kidneys to heal. Relatives have been raising money on GoFundMe to pay their bills.

Months after moving across the state to Amarillo and hoping for better days, Tim said he got good news this week: He no longer needs dialysis. A new round of tests found no signs of cancer. His white blood cell count is back to normal. His lymph nodes are no longer swollen.

He goes back for another scan in a few weeks, but the doctor told him she isn’t going to recommend any further chemo at this point.

“It was shocking, to tell you the truth. It still is. When I talk about it, I get kind of emotional” about his recovery, he said.

Tim said he was really dreading more chemotherapy. His hair has just started growing back. He can finally taste food again. He wasn’t ready to face more side effects from the treatments, or the COVID – he no longer knows exactly which diagnosis led to his most debilitating symptoms.

He said his ordeal has left him with no patience for health care workers who don’t think they need to be vaccinated.

The way he sees it, it’s no different than the electrical training he had to get before he could wire the lights and pumps in a swimming pool.

“You know, if I don’t certify and keep my license, I can’t work on anything electrical. So, if I’ve made the choice not to go down and take the test and get a license, then I made the choice not to work on electrical stuff,” he said.

He supports the growing number of hospitals that have made vaccination mandatory for their workers.

“They don’t let electricians put people at risk. And they shouldn’t let health care workers for sure,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tim Oswalt had been in a Fort Worth, Texas, hospital for over a month, receiving treatment for a grapefruit-sized tumor in his chest that was pressing on his heart and lungs. It turned out to be stage 3 non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Then one day in January, he was moved from his semi-private room to an isolated one with special ventilation. The staff explained he had been infected by the virus that was once again surging in many areas of the country, including Texas.

“How the hell did I catch COVID?” he asked the staff, who now approached him in full moon-suit personal protective equipment (PPE).

The hospital was locked down, and Mr. Oswalt hadn’t had any visitors in weeks. Neither of his two roommates tested positive. He’d been tested for COVID several times over the course of his nearly 5-week stay and was always negative.

“‘Well, you know, it’s easy to [catch it] in a hospital,’” Mr. Oswalt said he was told by hospital staff. “‘We’re having a bad outbreak. So you were just exposed somehow.’”

Officials at John Peter Smith Hospital, where Mr. Oswalt was treated, said they are puzzled by his case. According to their infection prevention team, none of his caregivers tested positive for COVID-19, nor did Mr. Oswalt share space with any other COVID-positive patients. And yet, local media reported a surge in cases among JPS hospital staff in December.

“Infection of any kind is a constant battle within hospitals and one that we all take seriously,” said Rob Stephenson, MD, chief quality officer at JPS Health Network. “Anyone in a vulnerable health condition at the height of the pandemic would have been at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 inside – or even more so, outside – the hospital.”

Mr. Oswalt was diagnosed with COVID in early January. JPS Hospital began vaccinating its health care workers about 2 weeks earlier, so there had not yet been enough time for any of them to develop full protection against catching or spreading the virus.

Today, the hospital said 74% of its staff – 5,300 of 7,200 workers – are now vaccinated.

against the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Refusing vaccinations

In fact, nationwide, 1 in 4 hospital workers who have direct contact with patients had not yet received a single dose of a COVID vaccine by the end of May, according to a WebMD and Medscape Medical News analysis of data collected by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from 2,500 hospitals across the United States.

Among the nation’s 50 largest hospitals, the percentage of unvaccinated health care workers appears to be even larger, about 1 in 3. Vaccination rates range from a high of 99% at Houston Methodist Hospital, which was the first in the nation to mandate the shots for its workers, to a low between 30% and 40% at some hospitals in Florida.

Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center in Houston has 1,180 beds and sits less than half a mile from Houston Methodist Hospital. But in terms of worker vaccinations, it is farther away.

Memorial Hermann reported to HHS that about 32% of its 28,000 workers haven’t been inoculated. The hospital’s PR office contests that figure, putting it closer to 25% unvaccinated across their health system. The hospital said it is boosting participation by offering a $300 “shot of hope” bonus to workers who start their vaccination series by the end of June.

Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla., reported to HHS that 63% of its health care personnel are still unvaccinated. The hospital did not return a call to verify that number.

To boost vaccination rates, more hospitals are starting to require the shots, after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission gave its green light to mandates in May.

“It’s a real problem that you have such high levels of unvaccinated individuals in hospitals,” said Lawrence Gostin, JD, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, Washington.

“We have to protect our health workforce, and we have to protect our patients. Hospitals should be the safest places in the country, and the only way to make them safe is to have a fully vaccinated workforce,” Mr. Gostin said.

Is the data misleading?

The HHS system designed to amass hospital data was set up quickly, to respond to an emergency. For that reason, experts say the information hasn’t been as carefully collected or vetted as it normally would have been. Some hospitals may have misunderstood how to report their vaccination numbers.

In addition, reporting data on worker vaccinations is voluntary. Only about half of hospitals have chosen to share their numbers. In other cases, like Texas, states have blocked the public release of these statistics.

AdventHealth Orlando, a 1,300-bed hospital in Florida, reported to HHS that 56% of its staff have not started their shots. But spokesman Jeff Grainger said the figures probably overstate the number of unvaccinated workers because the hospital doesn’t always know when people get vaccinated outside of its campus, at a local pharmacy, for example.

For those reasons, the picture of health care worker vaccinations across the country is incomplete.

Where hospitals fall behind

Even if the data are flawed, the vaccination rates from hospitals mirror the general population. A May Gallup poll, for example, found 24% of Americans said they definitely won’t get the vaccine. Another 12% say they plan to get it but are waiting.

The data also align with recent studies. A review of 35 studies by researchers at New Mexico State University that assessed hesitancy in more than 76,000 health care workers around the world found about 23% of them were reluctant to get the shots.

An ongoing monthly survey of more than 1.9 million U.S. Facebook users led by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh recently looked at vaccine hesitancy by occupation. It revealed a spectrum of hesitancy among health care workers corresponding to income and education, ranging from a low of 9% among pharmacists to highs of 20%-23% among nursing aides and emergency medical technicians. About 12% of registered nurses and doctors admitted to being hesitant to get a shot.

“Health care workers are not monolithic,” said study author Jagdish Khubchandani, professor of public health sciences at New Mexico State.

“There’s a big divide between males, doctoral degree holders, older people and the younger low-income, low-education frontline, female, health care workers. They are the most hesitant,” he said. Support staff typically outnumbers doctors at hospitals about 3 to 1.

“There is outreach work to be done there,” said Robin Mejia, PhD, director of the Statistics and Human Rights Program at Carnegie Mellon, who is leading the study on Facebook’s survey data. “These are also high-contact professions. These are people who are seeing patients on a regular basis.”

That’s why, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was planning the national vaccine rollout, they prioritized health care workers for the initially scarce first doses. The intent was to protect vulnerable workers and their patients who are at high risk of infection. But the CDC had another reason for putting health care workers first: After they were safely vaccinated, the hope was that they would encourage wary patients to do the same.

Hospitals were supposed to be hubs of education to help build trust within less confident communities. But not all hospitals have risen to that challenge.

Political affiliation seems to be one contributing factor in vaccine hesitancy. Take for example Calhoun, Ga., the seat of Gordon County, where residents voted for Donald Trump over Joe Biden by a 67-point margin in the 2020 general election. Studies have found that Republicans are more likely to decline vaccines than Democrats.

People who live in rural areas are less likely to be vaccinated than those who live in cities, and that’s true in Gordon County too. Vaccinations are lagging in this northwest corner of Georgia where factory jobs in chicken processing plants and carpet manufacturing energize the local economy. Just 24% of Gordon County residents are fully vaccinated, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

At AdventHealth Gordon, a 112-bed hospital in Calhoun, just 35% of the 1,723 workers that serve the hospital are at least partially vaccinated, according to data reported to HHS.

‘I am not vaccinated’

One reason some hospital staff say they are resisting COVID vaccination is because it’s so new and not yet fully approved by the FDA.

“I am not vaccinated,” said a social services worker for AdventHealth Gordon who asked that her name not be used because she was unauthorized to speak to this news organization and Georgia Health News (who collaborated on this project). “I just have not felt the need to do that at this time.”

The woman said she doesn’t have a problem with vaccines. She gets the flu shot every year. “I’ve been vaccinated all my life,” she said. But she doesn’t view COVID-19 vaccination in the same way.

“I want to see more testing done,” she said. “It took a long time to get a flu vaccine, and we made a COVID vaccine in 6 months. I want to know, before I start putting something into my body, that the testing is done.”

Staff at her hospital were given the option to be vaccinated or wear a mask. She chose the mask.

Many of her coworkers share her feelings, she said.

Mask expert Linsey Marr, PhD, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, Va., said N95 masks and vaccines are both highly effective, but the protection from the vaccine is superior because it is continuous.

“It’s hard to wear an N95 at all times. You have to take it off to eat, for example, in a break room in a hospital. I should point out that you can be exposed to the virus in other buildings besides a hospital – restaurants, stores, people’s homes – and because someone can be infected without symptoms, you could easily be around an infected person without knowing it,” she said.

Eventually, staff at AdventHealth Gordon may get a stronger nudge to get the shots. Chief Medical Officer Joseph Joyave, MD, said AdventHealth asks workers to get flu vaccines or provide the hospital with a reason why they won’t. He expects a similar policy will be adopted for COVID vaccines once they are fully licensed by the FDA.

In the meantime, he does not believe that the hospital is putting patients at risk with its low vaccination rate. “We continue to use PPE, masking in all clinical areas, and continue to screen daily all employees and visitors,” he said.

AdventHealth, the 12th largest hospital system in the nation with 49 hospitals, has at least 20 hospitals with vaccination rates lower than 50%, according to HHS data.

Other hospital systems have approached hesitation around the COVID vaccines differently.

When infectious disease experts at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville realized early on that many of their workers felt unsure about the vaccines, they set out to provide a wealth of information.

“There was a lot of hesitancy and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious disease at Vanderbilt. So the infectious disease division put together a multifaceted program including Q&As, educational sessions, and one-on-one visits with employees “from the custodians all the way up to the C-Suite,” he said.

Today, HHS data shows the hospital is 83% vaccinated. Dr. Schaffner thinks the true number is probably higher, about 90%. “We’re very pleased with that,” he said.

In his experience with flu vaccinations, it was extremely difficult in the first year to get workers to take flu shots. The second year it was easier. By the third year it was humdrum, he said, because it had become a cultural norm.

Dr. Schaffner expects winning people over to the COVID vaccines will follow a similar course, but “we’re not there yet,” he said.

Protecting patients and caregivers

There is no question that health care workers carried a heavy load through the worst months of the pandemic. Many of them worked to the point of exhaustion and burnout. Some were the only conduits between isolated patients and their families, holding hands and mobile phones so distanced loved ones could video chat. Many were left inadequately protected because of shortages of masks, gowns, gloves, and other gear.

An investigation by Kaiser Health News and The Guardian recently revealed that more than 3,600 health care workers died in COVID’s first year in the United States.

Vaccination of health care workers is important to protect these frontline workers and their families who will continue to be at risk of coming into contact with the infection, even as the number of cases falls.

Hesitancy in health care is also dangerous because these clinicians and allied health workers – who may not show any symptoms – can also carry the virus to someone who wouldn’t survive an infection, including patients with organ transplants, those with autoimmune diseases, premature infants, and the elderly.

It is not known how often patients in the United States are infected with COVID in health care settings, but case reports reveal that hospitals are still experiencing outbreaks.

On June 1, Northern Lights A.R. Gould Hospital in Presque Isle, Maine, announced a COVID outbreak on its medical-surgical unit. As of June 22, 13 residents and staff have caught the virus, according to the Maine Centers for Disease Control, which is investigating. Four of the first five staff members to test positive had not been fully vaccinated.

According to HHS data, about 20% of the health care workers at that hospital are still unvaccinated.

Oregon Health & Science University experienced a COVID outbreak connected to the hospital’s cardiovascular care unit from April to mid-May of this year. According to hospital spokesperson Tracy Brawley, a patient visitor brought the infection to campus, where it ultimately spread to 14 others, including “patients, visitors, employees, and learners.”

In a written statement, the hospital said “nearly all” health care workers who tested positive were previously vaccinated and experienced no symptoms or only minor ones. The hospital said it hasn’t identified any onward transmission from health care workers to patients, and also stated: “It is not yet understood how transmission may have occurred between patients, visitors, and health care workers.”

In March, an unvaccinated health care worker in Kentucky carried a SARS-CoV-2 variant back to the nursing home where the person worked. Some 90% of the residents were fully vaccinated. Ultimately, 26 patients were infected; 18 of them were fully vaccinated. And 20 health care workers, four of whom were vaccinated, were infected.

Vaccines slowed the virus down and made infections less severe, but in this fragile population, they couldn’t stop it completely. One resident, who had survived a bout of COVID almost a year earlier, died. According to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47% of the workers in that facility were unvaccinated.

In the United Kingdom, statistics collected through that country’s National Health Service also suggest a heavy toll. More than 32,300 patients caught COVID in English hospitals since March 2020. Up to 8,700 of them died, according to a recent analysis by The Guardian. The U.K. government recently made COVID vaccinations mandatory for health care workers.

COVID delays cancer care

When Mr. Oswalt, the Fort Worth, Texas man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, contracted COVID-19, the virus took down his kidneys first. Toxins were building up in his blood, so doctors prescribed dialysis to support his body and buy his kidneys time to heal.

He was in one of these dialysis treatments when his lungs succumbed.

“Look, I can’t breathe,” he told the nurse who was supervising his treatment. The nurse gestured to an oxygen tank already hanging by his side, and said, “You should be OK.”

But he wasn’t.

“I can’t breathe,” Mr. Oswalt said again. Then the air hunger hit. Mr. Oswalt began gasping and couldn’t stop. Today, his voice breaks when he describes this moment. “A lot of it becomes a blur.”

When Mr. Oswalt, 61, regained consciousness, he was hooked up to a ventilator to ease his breathing.

For days, Mr. Oswalt clung to the edge of life. His wife, Molly, who wasn’t allowed to see him in the hospital, got a call that he might not make it through the night. She made frantic phone calls to her brother and sister and prayed.

Mr. Oswalt was on a ventilator for about a week. His kidneys and lungs healed enough so that he could restart his chemotherapy. He was eventually discharged home on January 22.

The last time he was scanned, the large tumor in his chest had shrunk from the size of a grapefruit to the size of a dime.

But having COVID on top of cancer has had a devastating effect on his life. Before he got sick, Molly said, he couldn’t stay still. He was busy all the time. After spending months in the hospital, his energy was depleted. He couldn’t keep his swimming pool installation business going.

He and Molly had to give up their house in Fort Worth and move in with family in Amarillo. He has had to pause his cancer treatments while doctors wait for his kidneys to heal. Relatives have been raising money on GoFundMe to pay their bills.

Months after moving across the state to Amarillo and hoping for better days, Tim said he got good news this week: He no longer needs dialysis. A new round of tests found no signs of cancer. His white blood cell count is back to normal. His lymph nodes are no longer swollen.

He goes back for another scan in a few weeks, but the doctor told him she isn’t going to recommend any further chemo at this point.

“It was shocking, to tell you the truth. It still is. When I talk about it, I get kind of emotional” about his recovery, he said.

Tim said he was really dreading more chemotherapy. His hair has just started growing back. He can finally taste food again. He wasn’t ready to face more side effects from the treatments, or the COVID – he no longer knows exactly which diagnosis led to his most debilitating symptoms.

He said his ordeal has left him with no patience for health care workers who don’t think they need to be vaccinated.

The way he sees it, it’s no different than the electrical training he had to get before he could wire the lights and pumps in a swimming pool.

“You know, if I don’t certify and keep my license, I can’t work on anything electrical. So, if I’ve made the choice not to go down and take the test and get a license, then I made the choice not to work on electrical stuff,” he said.

He supports the growing number of hospitals that have made vaccination mandatory for their workers.

“They don’t let electricians put people at risk. And they shouldn’t let health care workers for sure,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why getting a COVID-19 vaccine to children could take time

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.

The FDA is considering different approaches to figure out whether a vaccine would be effective in kids, including something called an “immunobridging trial.”

In bridging trials, researchers don’t look for infections; rather, they look for proven signs that someone has developed immunity, like antibody levels. Those biomarkers are then compared to the immune responses of younger adults who have demonstrated good protection against infection.

The main advantage of bridging studies is speed. It’s possible to get a snapshot of how the immune system responds to a vaccine within weeks of the final dose.

The drawback is that researchers don’t know exactly what to look for to judge how well the shots are generating protection.

That’s made even more difficult because kids’ immune systems are still developing, so it may be tough to draw direct parallels to adults.

“We don’t know what the serologic correlate of immunity is now. We don’t know how much antibody you have to get in order to be protected. We don’t know what the role of T cells will be,” said H. Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

“I have so much sympathy for the FDA because these are enormous problems, and you have to make a decision,” said Dr. Meissner, who is a member of the FDA’s vaccines and related biological products advisory committee.

Speed vaccines to market, or gather more data?

The plummeting rate of infections in the United States also means that it may be more difficult for the FDA to justify allowing a vaccine on the market for emergency use for children under age 12.

In its recent advisory committee meeting, the agency asked the panel whether it should consider COVID vaccines for children under an EUA or a biologics license application (BLA), aka full approval.

A BLA typically means the agency considers a year or two of data on a new product, rather than just 2 months’ worth. Emergency use also allows products on the market under a looser standard – they “may be” safe and effective, instead of has been proven to be safe and effective.

Several committee members said they didn’t feel the United States was still in an emergency with COVID and couldn’t see the FDA allowing a vaccine to be used in kids that wasn’t given the agency’s highest level of scrutiny, particularly with reports of adverse events like myocarditis coming to light.

“I just want to be sure the price we pay for vaccinating millions of children justifies the side effects, and I don’t think we know that yet,” Dr. Meissner said.

Others acknowledged that there was little risk to kids now with infections on the decline but said that picture could change as variants spread, schools reopen, and colder temperatures force people indoors.

The FDA must decide whether to act based on where we are now or where we could be in a few months.

“I think it’s the million-dollar question right now,” said Hannah Kirking, MD, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who presented new and unpublished data on COVID’s impact in children to the FDA’s advisory committee.

She said prospective studies tracking the way COVID moves through a household with weekly testing from New York City and Utah had found that children catch and transmit COVID almost as readily as adults. But they don’t usually get as sick as adults do, so their cases are easy to miss.

She also presented the results of blood tests from samples around the country looking for evidence of past infection. In these seroprevalence studies, about 27% of children under age 17 had antibodies to COVID – the most of any age group. So more than 1 in 4 kids already has some natural immunity.

That means the main benefit of vaccinating children might be the protection of others, while they still bear the risks – however tiny.

Some experts felt that wasn’t enough reason to justify mass distribution of the vaccines to kids, and from a regulatory standpoint, it might not be permissible.

“FDA can only approve a medical product in a population if the benefits outweigh the risks in that population,” said Peter Doshi, PhD, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research in the University of Maryland’s school of pharmacy, Baltimore.

“If benefits don’t outweigh risks in children, it can’t be indicated for children. Full stop,” said Dr. Doshi, who is also an editor at the BMJ.

He said there’s another way to give children access to vaccines, through an expanded access or compassionate use program. Because most COVID deaths have been in children with underlying health conditions, Dr. Doshi and others said it might make sense to allow expanded access – which would get vaccines to children at high risk for complications – without turning them loose on millions before they are more thoroughly studied.

“It’s not a particularly attractive option for industry, because there’s no money to be made. Your medicine can’t be commercialized under expanded access. The most you can reap is manufacturing cost, which is not a lot,” he said.

Art Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone medical center, said the argument for vaccinating children for flu falls along the same lines. The benefit-to-risk ratio is finely balanced in children. The main value of protecting them is to protect others.

“Flu rarely kills young folks. But you’re really trying to protect old folks and that’s the classic example,” he said.

What’s more, he said the idea that children would take on some risk with a vaccine for little personal benefit is oversimplified.

“Yes, you might get vaccinated to prevent harm to others, but those others are providing benefits to you. It’s not a one-way street. I think that’s a little morally distorted,” Mr. Caplan said. “Being able to keep society open benefits kids and adults alike.”

Other committee members felt like it was too early to sound the all-clear on COVID and said the FDA should authorize vaccines for children as quickly as it had for other age groups.

“We are still, I believe, in an emergency situation. I think that when this virus goes into our children, which is what it’s going to do, that will give it an incubator to change,” said Oveta Fuller, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.