User login

Tender Dermal Nodule on the Temple

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma

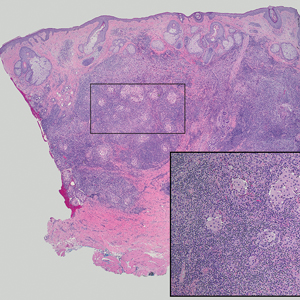

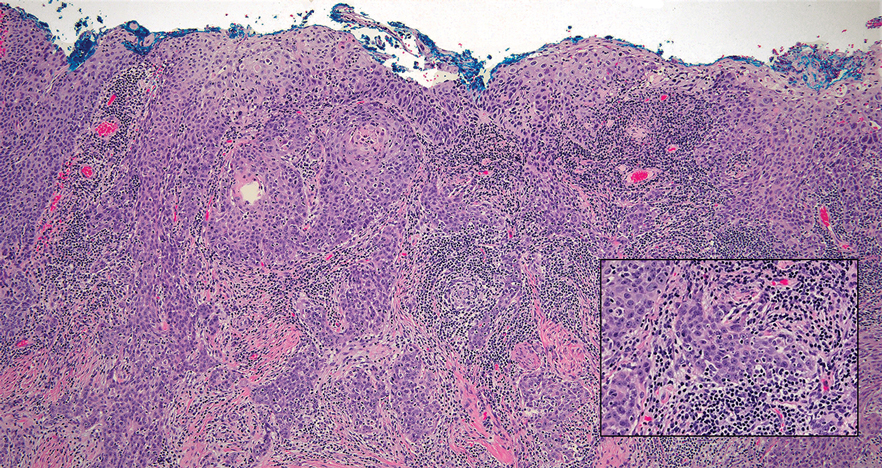

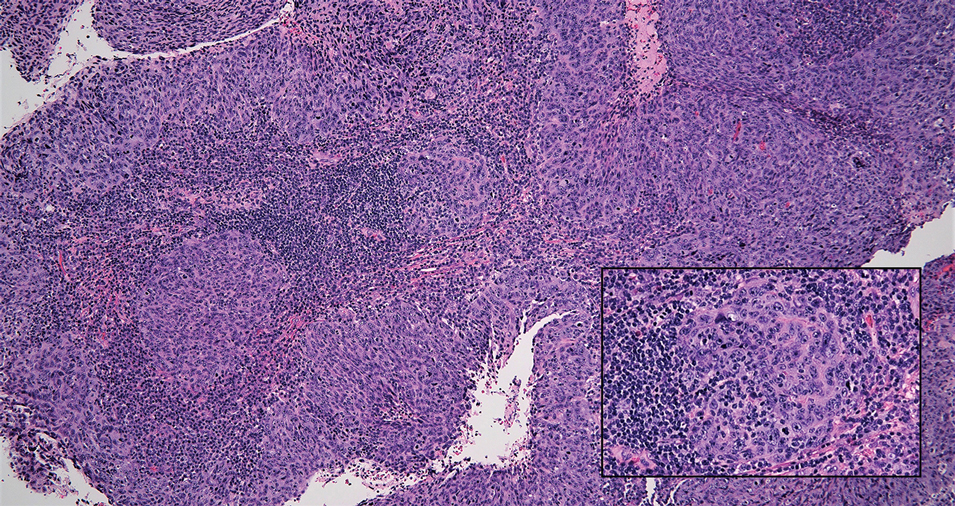

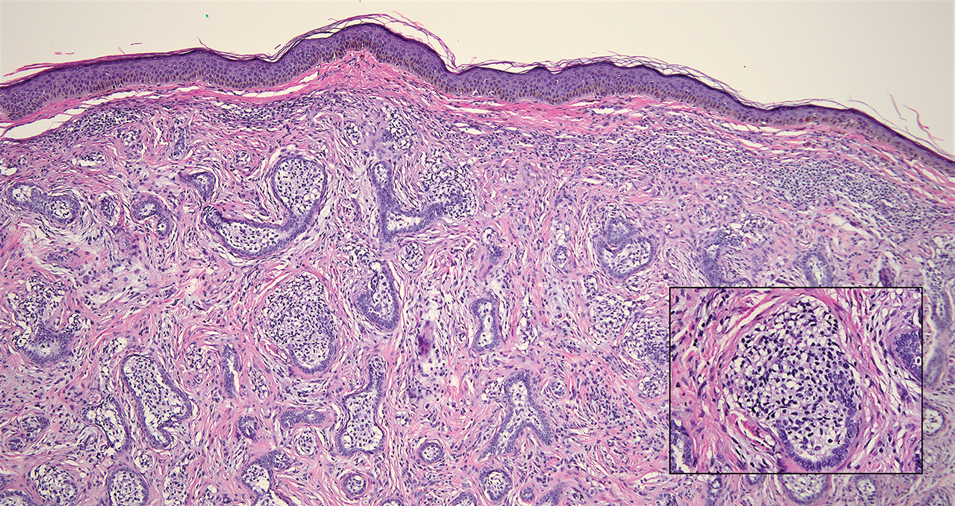

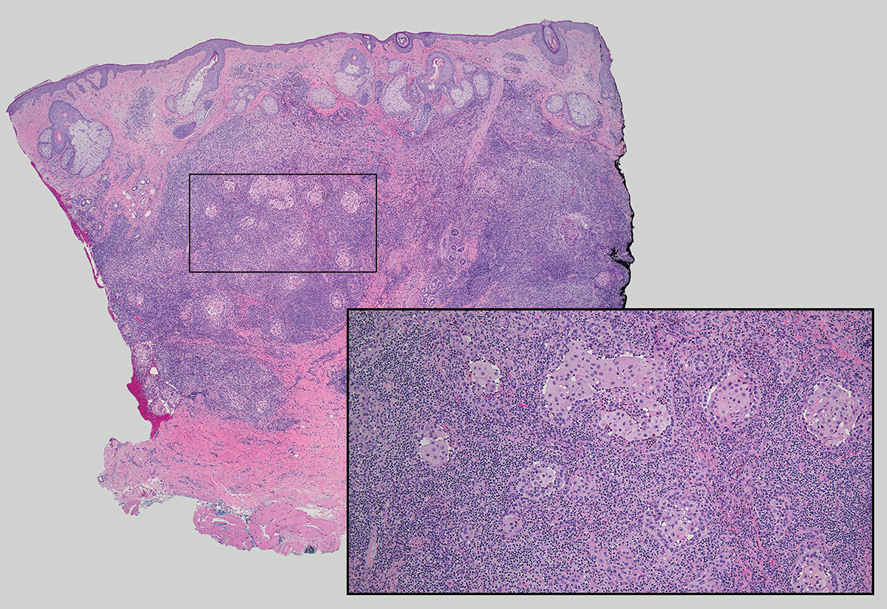

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare, poorly differentiated, primary cutaneous neoplasm that occurs on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the head and neck of elderly individuals. It often manifests as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, flesh-colored or erythematous dermal nodule, though ulceration and tenderness have been reported.1 Histopathologically, these neoplasms often are poorly circumscribed and can infiltrate surrounding subcutaneous and soft tissue. As a biphasic tumor, LELC is characterized by islands, nests, or trabeculae of epithelioid cells within the mid dermis surrounded by a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with plasma cells (Figure 1).1 The epithelial component rarely communicates with the overlying epidermis and is composed of atypical polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitosis.2 These epithelial nests can be highlighted by pancytokeratin AE1/AE3 or other epithelial differentiation markers (eg, CAM 5.2, CK5/6, epithelial membrane antigen, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin), while the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate consists of an admixture of T cells and B cells. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas also can demonstrate sebaceous, eccrine, or follicular differentiations.3 The epithelial nests of LELC also are positive for p63 and epithelial membrane antigen.2

The usual treatment of LELC is wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Despite the poorly differentiated morphology of the tumor, LELC has a generally good prognosis with low metastatic potential and few reports of local recurrence after incomplete excision.3 Patients who are not candidates for surgery as well as recalcitrant cases are managed with radiotherapy.1

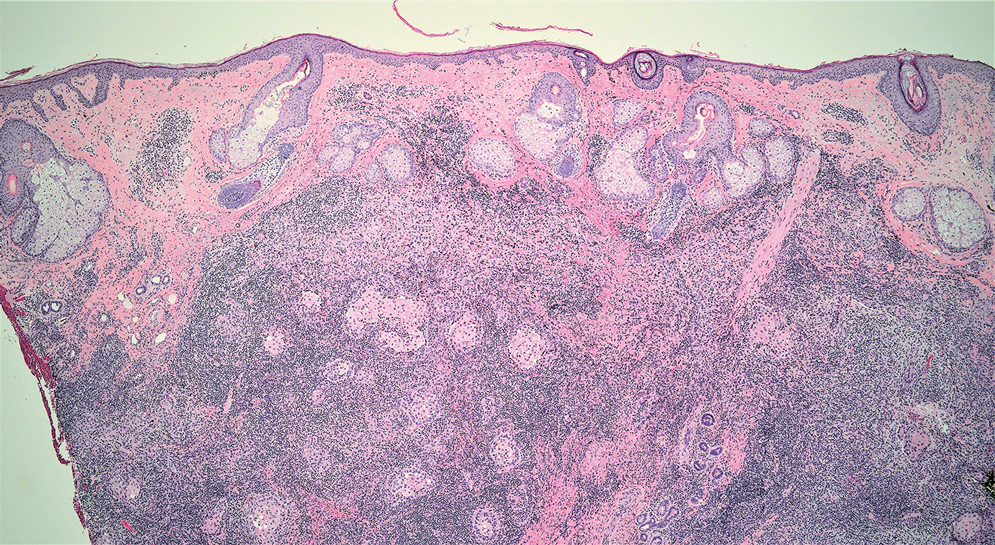

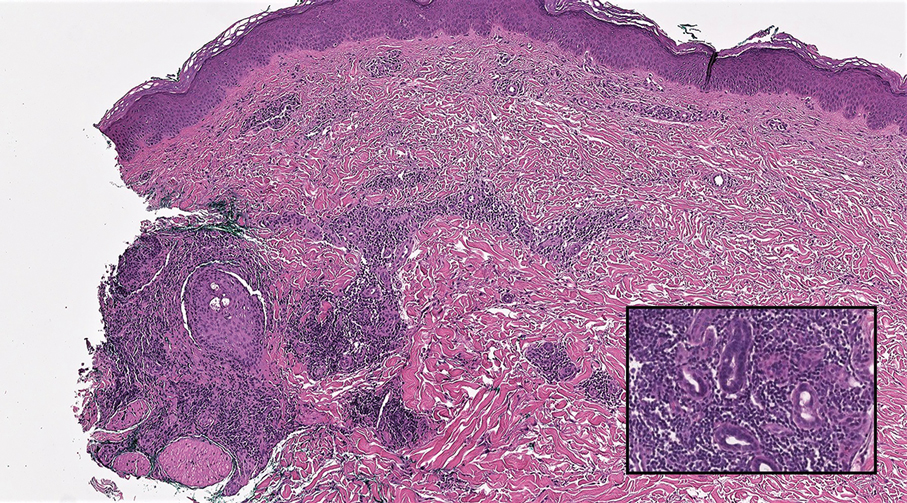

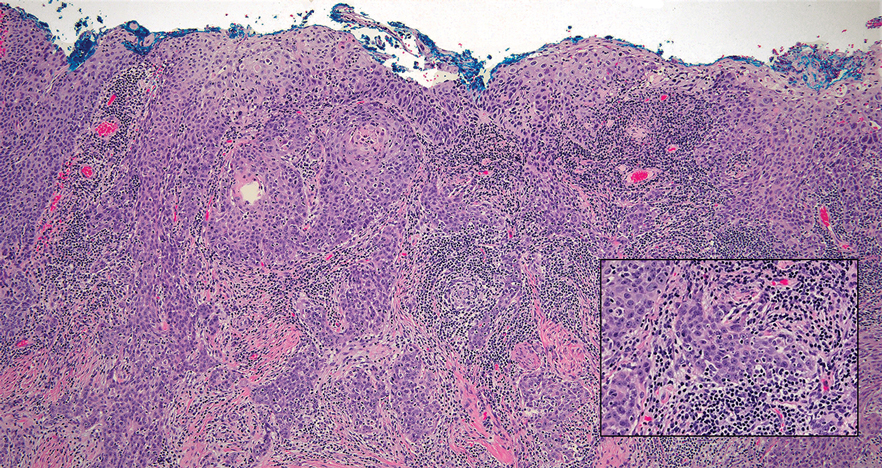

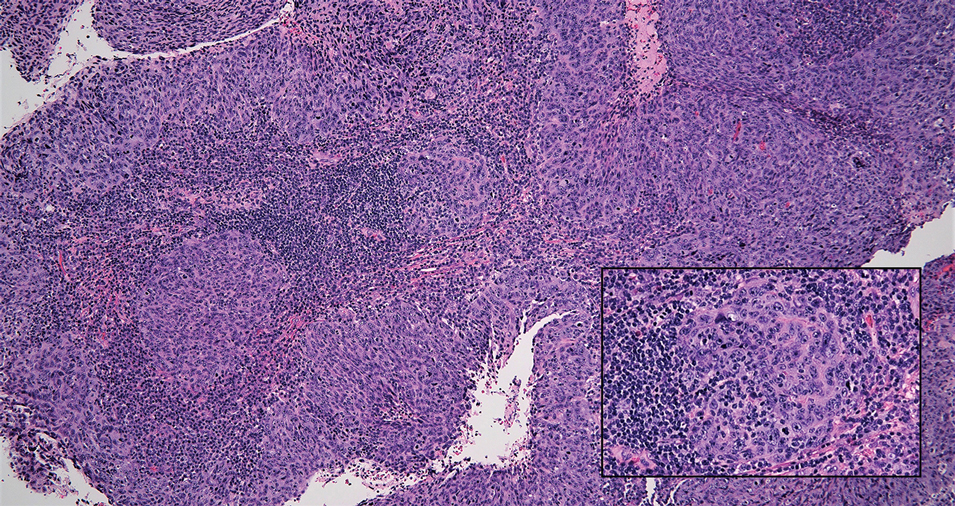

Cutaneous lymphadenoma (CL) is a benign adnexal neoplasm that manifests as a small, solitary, fleshcolored nodule usually in the head and neck region.4 Histologically, CL consists of well-circumscribed epithelial nests within the dermis that are peripherally outlined by palisading basaloid cells and filled with clear to eosinophilic epithelioid cells (Figure 2).5 The fibrotic tumor stroma often is infiltrated by numerous intralobular dendritic cells and lymphocytes that occasionally can be arranged in germinal center–like nodules.4 The lymphoepithelial nature of CL can be challenging to distinguish morphologically from LELC, and immunohistochemistry stains may be required. In CL, both the basaloid and epithelioid cells stain positive for pancytokeratin AE1/ AE3, but the peripheral palisaded basaloid cells also stain positive for BerEP4. Additionally, the fibrotic stroma can be highlighted by CD34 and the intralobular dendritic cells by S-100.4

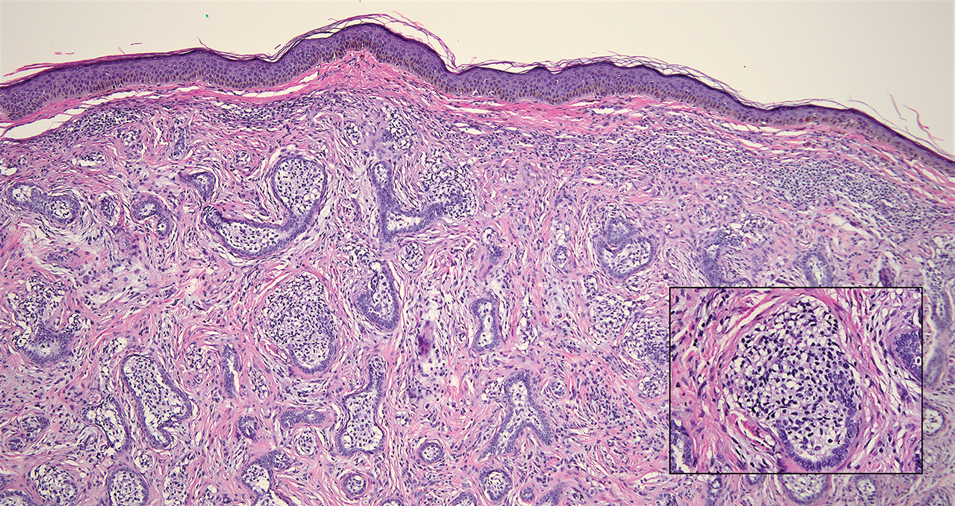

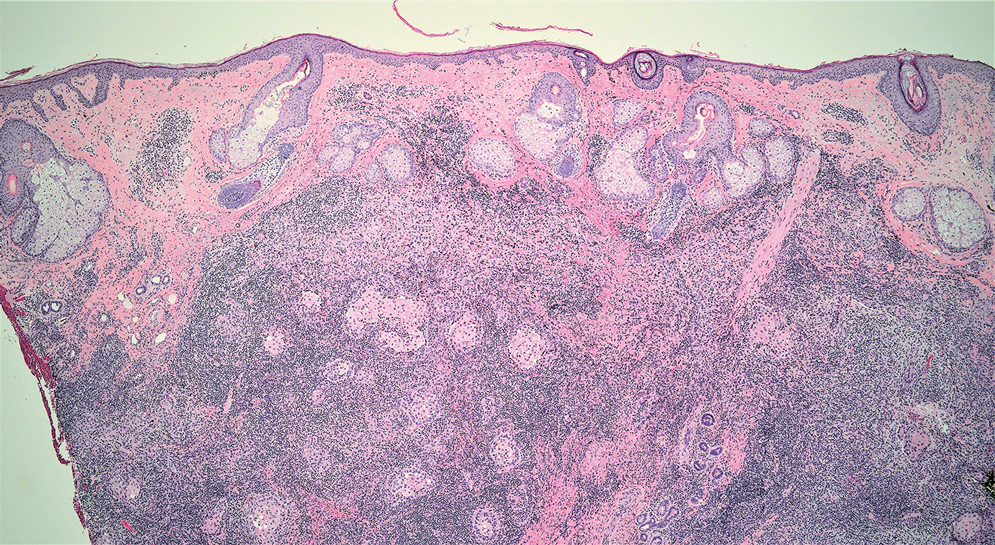

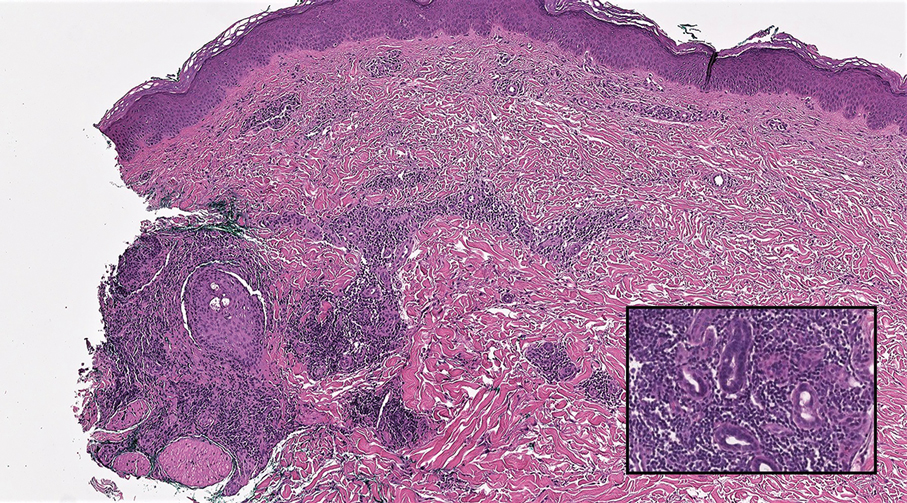

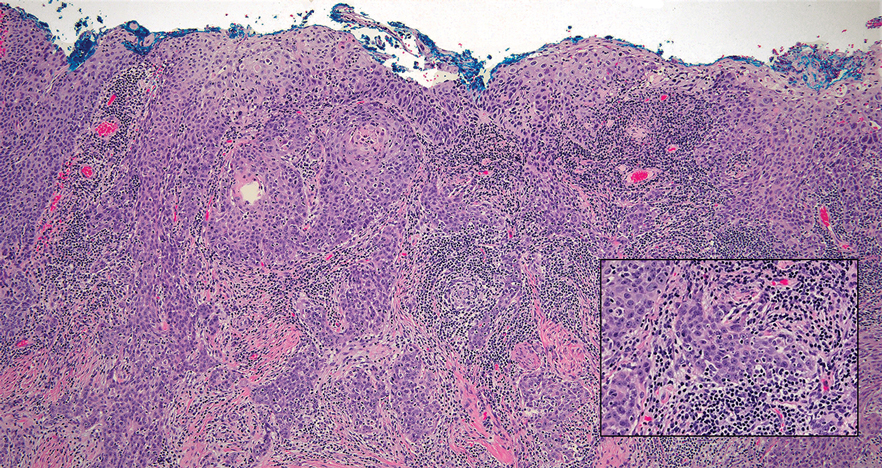

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), formerly known as lymphoepithelioma, refers to carcinoma arising within the epithelium of the nasopharynx.6 Endemic to China, NPC manifests as an enlarging nasopharyngeal mass, causing clinical symptoms such as nasal obstruction and epistaxis.7 Histologically, nonkeratinizing NPC exhibits a biphasic morphology consisting of epithelioid neoplastic cells and background lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 3). The epithelial component consists of round to oval neoplastic cells with amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli.6 Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is associated strongly with the Epstein-Barr virus while LELC is not; thus, Epstein- Barr encoding region in situ hybridization can reliably distinguish these entities. Metastatic NPC is rare but has been reported; therefore, it is highly recommended to perform an otolaryngologic examination in addition to testing for Epstein-Barr virus reactivity as part of a complete evaluation.8

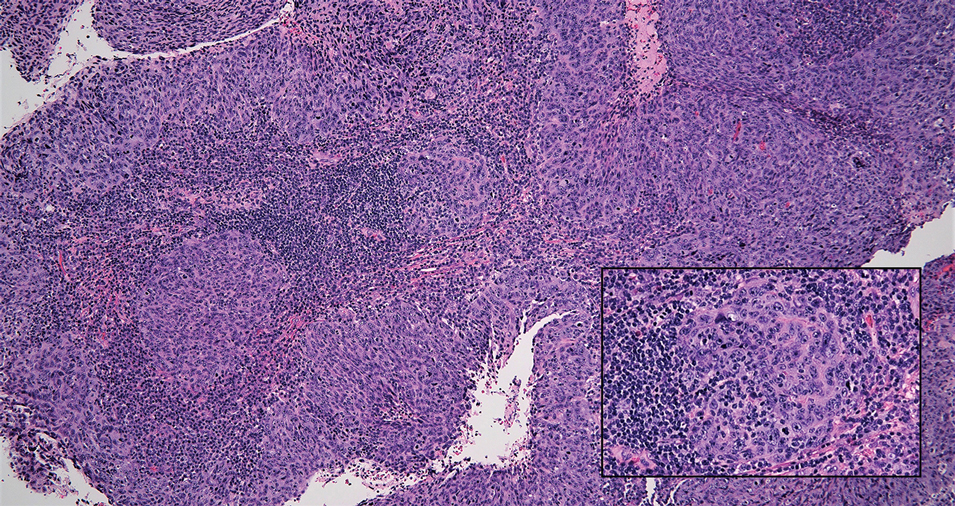

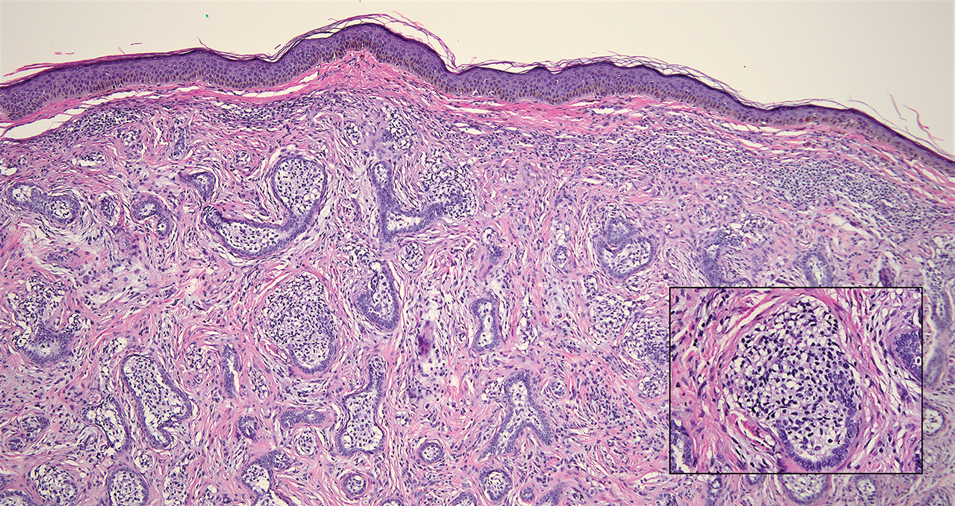

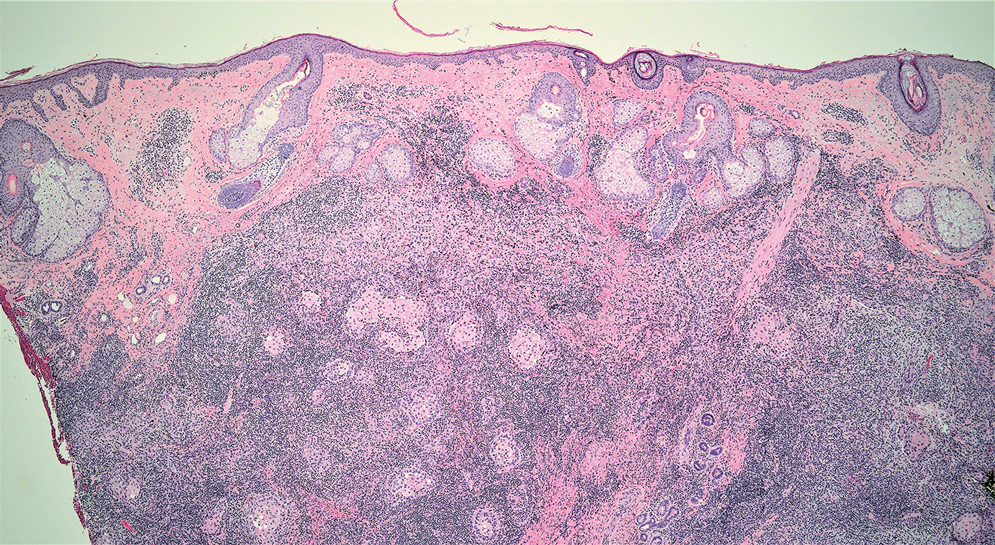

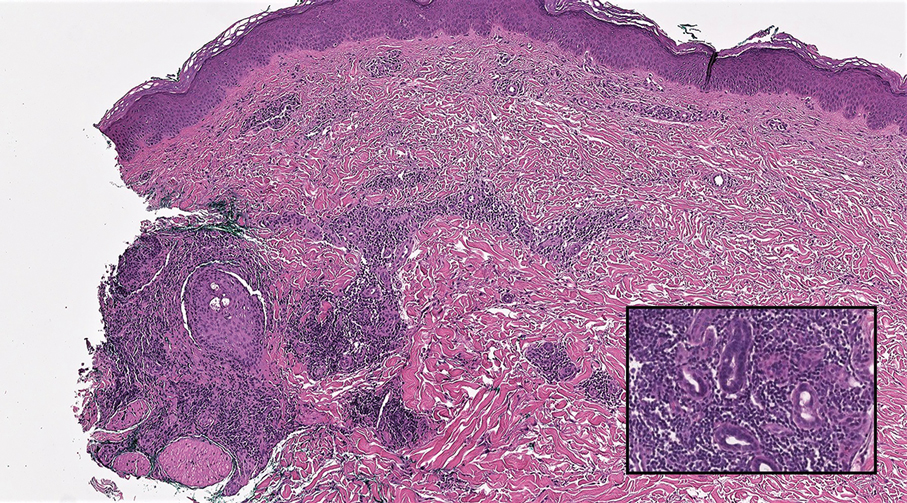

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a common epidermal malignancy with multiple subtypes and variable morphology. The clinical presentation of SCC is similar to LELC—an enlarging hyperkeratotic papule or nodule on sun-exposed skin that often is ulcerated and tender.9 Histologically, poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing SCC can form nests and trabeculae of epithelioid cells that are stained by epithelial differentiation markers, resembling the epithelioid nests of LELC. Distinguishing between LELC and poorly differentiated SCC with robust inflammatory infiltrate can be challenging (Figure 4). In fact, some experts support LELC as an SCC variant rather than a separate entity.9 However, in contrast to LELC, the dermal nests of SCC usually maintain an epidermal connection and often are associated with an overlying area of SCC in situ or welldifferentiated SCC.3

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, accounting for almost 50% of all reported cases.10 Classic MF has an indolent course and progresses through several clinical stages. Patches and plaques characterize early stages; lymphadenopathy indicates progression to later stages in which erythroderma may develop with coalescence of patches, plaques, and tumors; and MF present in blood or lymph nodes characterizes the late stage. Each stage of MF is different histologically—from a superficial lichenoid infiltrate with exocytosis of malignant T cells in the patch stage, to more robust epidermotropism and dermal infiltrate in the plaque stage, and finally a dense dermal infiltrate in the late stage.11 The rare syringotropic variant of MF clinically manifests as solitary or multiple erythematous lesions, often with overlying alopecia. Syringotropic MF uniquely exhibits folliculotropism and syringotropism along with syringometaplasia on histologic evaluation (Figure 5).12 The syringometaplasia can be difficult to distinguish from the epithelial nests of LELC, particularly with the lymphocytic background. Immunohistochemical panels for T-cell markers can highlight aberrant T cells in syringotropic MF through their usual loss of CD5 and CD7, in comparison to normal T cells in LELC.11 An elevated CD4:CD8 ratio of 4:1 and molecular analysis for T-cell receptor gene clonal rearrangements also can support the diagnosis of MF.12

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Fisher JC, White RM, Hurd DS. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case of one patient presenting with two primary cutaneous neoplasms. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. 2015;33:40-41.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Yu R, Salama S, Alowami S. Cutaneous lymphadenoma: a rare case and brief review of a diagnostic pitfall. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5358.

- Monteagudo C, Fúnez R, Sánchez-Sendra B, et al. Cutaneous lymphadenoma is a distinct trichoblastoma-like lymphoepithelial tumor with diffuse androgen receptor immunoreactivity, Notch1 ligand in Reed-Sternberg-like Cells, and common EGFR somatic mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1382-1390.

- Stelow EB, Wenig BM. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: nasopharynx. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:16-22.

- Almomani MH, Zulfiqar H, Nagalli S. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC, lymphoepithelioma). StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Lassen CB, Lock-Andersen J. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with perineural invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:E252.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Pileri A, Facchetti F, Rütten A, et al. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare variant of the disease with peculiar clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:100-109.

- Ryu HJ, Kim SI, Jang HO, et al. Evaluation of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides [published October 15, 2021]. Cells. 2021;10:2758. doi:10.3390/cells10102758

- Lehmer LM, Amber KT, de Feraudy SM. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma enabling a histopathologic “sigh of relief.” Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:920-923.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare, poorly differentiated, primary cutaneous neoplasm that occurs on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the head and neck of elderly individuals. It often manifests as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, flesh-colored or erythematous dermal nodule, though ulceration and tenderness have been reported.1 Histopathologically, these neoplasms often are poorly circumscribed and can infiltrate surrounding subcutaneous and soft tissue. As a biphasic tumor, LELC is characterized by islands, nests, or trabeculae of epithelioid cells within the mid dermis surrounded by a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with plasma cells (Figure 1).1 The epithelial component rarely communicates with the overlying epidermis and is composed of atypical polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitosis.2 These epithelial nests can be highlighted by pancytokeratin AE1/AE3 or other epithelial differentiation markers (eg, CAM 5.2, CK5/6, epithelial membrane antigen, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin), while the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate consists of an admixture of T cells and B cells. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas also can demonstrate sebaceous, eccrine, or follicular differentiations.3 The epithelial nests of LELC also are positive for p63 and epithelial membrane antigen.2

The usual treatment of LELC is wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Despite the poorly differentiated morphology of the tumor, LELC has a generally good prognosis with low metastatic potential and few reports of local recurrence after incomplete excision.3 Patients who are not candidates for surgery as well as recalcitrant cases are managed with radiotherapy.1

Cutaneous lymphadenoma (CL) is a benign adnexal neoplasm that manifests as a small, solitary, fleshcolored nodule usually in the head and neck region.4 Histologically, CL consists of well-circumscribed epithelial nests within the dermis that are peripherally outlined by palisading basaloid cells and filled with clear to eosinophilic epithelioid cells (Figure 2).5 The fibrotic tumor stroma often is infiltrated by numerous intralobular dendritic cells and lymphocytes that occasionally can be arranged in germinal center–like nodules.4 The lymphoepithelial nature of CL can be challenging to distinguish morphologically from LELC, and immunohistochemistry stains may be required. In CL, both the basaloid and epithelioid cells stain positive for pancytokeratin AE1/ AE3, but the peripheral palisaded basaloid cells also stain positive for BerEP4. Additionally, the fibrotic stroma can be highlighted by CD34 and the intralobular dendritic cells by S-100.4

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), formerly known as lymphoepithelioma, refers to carcinoma arising within the epithelium of the nasopharynx.6 Endemic to China, NPC manifests as an enlarging nasopharyngeal mass, causing clinical symptoms such as nasal obstruction and epistaxis.7 Histologically, nonkeratinizing NPC exhibits a biphasic morphology consisting of epithelioid neoplastic cells and background lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 3). The epithelial component consists of round to oval neoplastic cells with amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli.6 Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is associated strongly with the Epstein-Barr virus while LELC is not; thus, Epstein- Barr encoding region in situ hybridization can reliably distinguish these entities. Metastatic NPC is rare but has been reported; therefore, it is highly recommended to perform an otolaryngologic examination in addition to testing for Epstein-Barr virus reactivity as part of a complete evaluation.8

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a common epidermal malignancy with multiple subtypes and variable morphology. The clinical presentation of SCC is similar to LELC—an enlarging hyperkeratotic papule or nodule on sun-exposed skin that often is ulcerated and tender.9 Histologically, poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing SCC can form nests and trabeculae of epithelioid cells that are stained by epithelial differentiation markers, resembling the epithelioid nests of LELC. Distinguishing between LELC and poorly differentiated SCC with robust inflammatory infiltrate can be challenging (Figure 4). In fact, some experts support LELC as an SCC variant rather than a separate entity.9 However, in contrast to LELC, the dermal nests of SCC usually maintain an epidermal connection and often are associated with an overlying area of SCC in situ or welldifferentiated SCC.3

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, accounting for almost 50% of all reported cases.10 Classic MF has an indolent course and progresses through several clinical stages. Patches and plaques characterize early stages; lymphadenopathy indicates progression to later stages in which erythroderma may develop with coalescence of patches, plaques, and tumors; and MF present in blood or lymph nodes characterizes the late stage. Each stage of MF is different histologically—from a superficial lichenoid infiltrate with exocytosis of malignant T cells in the patch stage, to more robust epidermotropism and dermal infiltrate in the plaque stage, and finally a dense dermal infiltrate in the late stage.11 The rare syringotropic variant of MF clinically manifests as solitary or multiple erythematous lesions, often with overlying alopecia. Syringotropic MF uniquely exhibits folliculotropism and syringotropism along with syringometaplasia on histologic evaluation (Figure 5).12 The syringometaplasia can be difficult to distinguish from the epithelial nests of LELC, particularly with the lymphocytic background. Immunohistochemical panels for T-cell markers can highlight aberrant T cells in syringotropic MF through their usual loss of CD5 and CD7, in comparison to normal T cells in LELC.11 An elevated CD4:CD8 ratio of 4:1 and molecular analysis for T-cell receptor gene clonal rearrangements also can support the diagnosis of MF.12

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare, poorly differentiated, primary cutaneous neoplasm that occurs on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the head and neck of elderly individuals. It often manifests as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, flesh-colored or erythematous dermal nodule, though ulceration and tenderness have been reported.1 Histopathologically, these neoplasms often are poorly circumscribed and can infiltrate surrounding subcutaneous and soft tissue. As a biphasic tumor, LELC is characterized by islands, nests, or trabeculae of epithelioid cells within the mid dermis surrounded by a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with plasma cells (Figure 1).1 The epithelial component rarely communicates with the overlying epidermis and is composed of atypical polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitosis.2 These epithelial nests can be highlighted by pancytokeratin AE1/AE3 or other epithelial differentiation markers (eg, CAM 5.2, CK5/6, epithelial membrane antigen, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin), while the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate consists of an admixture of T cells and B cells. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas also can demonstrate sebaceous, eccrine, or follicular differentiations.3 The epithelial nests of LELC also are positive for p63 and epithelial membrane antigen.2

The usual treatment of LELC is wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Despite the poorly differentiated morphology of the tumor, LELC has a generally good prognosis with low metastatic potential and few reports of local recurrence after incomplete excision.3 Patients who are not candidates for surgery as well as recalcitrant cases are managed with radiotherapy.1

Cutaneous lymphadenoma (CL) is a benign adnexal neoplasm that manifests as a small, solitary, fleshcolored nodule usually in the head and neck region.4 Histologically, CL consists of well-circumscribed epithelial nests within the dermis that are peripherally outlined by palisading basaloid cells and filled with clear to eosinophilic epithelioid cells (Figure 2).5 The fibrotic tumor stroma often is infiltrated by numerous intralobular dendritic cells and lymphocytes that occasionally can be arranged in germinal center–like nodules.4 The lymphoepithelial nature of CL can be challenging to distinguish morphologically from LELC, and immunohistochemistry stains may be required. In CL, both the basaloid and epithelioid cells stain positive for pancytokeratin AE1/ AE3, but the peripheral palisaded basaloid cells also stain positive for BerEP4. Additionally, the fibrotic stroma can be highlighted by CD34 and the intralobular dendritic cells by S-100.4

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), formerly known as lymphoepithelioma, refers to carcinoma arising within the epithelium of the nasopharynx.6 Endemic to China, NPC manifests as an enlarging nasopharyngeal mass, causing clinical symptoms such as nasal obstruction and epistaxis.7 Histologically, nonkeratinizing NPC exhibits a biphasic morphology consisting of epithelioid neoplastic cells and background lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 3). The epithelial component consists of round to oval neoplastic cells with amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli.6 Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is associated strongly with the Epstein-Barr virus while LELC is not; thus, Epstein- Barr encoding region in situ hybridization can reliably distinguish these entities. Metastatic NPC is rare but has been reported; therefore, it is highly recommended to perform an otolaryngologic examination in addition to testing for Epstein-Barr virus reactivity as part of a complete evaluation.8

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a common epidermal malignancy with multiple subtypes and variable morphology. The clinical presentation of SCC is similar to LELC—an enlarging hyperkeratotic papule or nodule on sun-exposed skin that often is ulcerated and tender.9 Histologically, poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing SCC can form nests and trabeculae of epithelioid cells that are stained by epithelial differentiation markers, resembling the epithelioid nests of LELC. Distinguishing between LELC and poorly differentiated SCC with robust inflammatory infiltrate can be challenging (Figure 4). In fact, some experts support LELC as an SCC variant rather than a separate entity.9 However, in contrast to LELC, the dermal nests of SCC usually maintain an epidermal connection and often are associated with an overlying area of SCC in situ or welldifferentiated SCC.3

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, accounting for almost 50% of all reported cases.10 Classic MF has an indolent course and progresses through several clinical stages. Patches and plaques characterize early stages; lymphadenopathy indicates progression to later stages in which erythroderma may develop with coalescence of patches, plaques, and tumors; and MF present in blood or lymph nodes characterizes the late stage. Each stage of MF is different histologically—from a superficial lichenoid infiltrate with exocytosis of malignant T cells in the patch stage, to more robust epidermotropism and dermal infiltrate in the plaque stage, and finally a dense dermal infiltrate in the late stage.11 The rare syringotropic variant of MF clinically manifests as solitary or multiple erythematous lesions, often with overlying alopecia. Syringotropic MF uniquely exhibits folliculotropism and syringotropism along with syringometaplasia on histologic evaluation (Figure 5).12 The syringometaplasia can be difficult to distinguish from the epithelial nests of LELC, particularly with the lymphocytic background. Immunohistochemical panels for T-cell markers can highlight aberrant T cells in syringotropic MF through their usual loss of CD5 and CD7, in comparison to normal T cells in LELC.11 An elevated CD4:CD8 ratio of 4:1 and molecular analysis for T-cell receptor gene clonal rearrangements also can support the diagnosis of MF.12

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Fisher JC, White RM, Hurd DS. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case of one patient presenting with two primary cutaneous neoplasms. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. 2015;33:40-41.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Yu R, Salama S, Alowami S. Cutaneous lymphadenoma: a rare case and brief review of a diagnostic pitfall. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5358.

- Monteagudo C, Fúnez R, Sánchez-Sendra B, et al. Cutaneous lymphadenoma is a distinct trichoblastoma-like lymphoepithelial tumor with diffuse androgen receptor immunoreactivity, Notch1 ligand in Reed-Sternberg-like Cells, and common EGFR somatic mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1382-1390.

- Stelow EB, Wenig BM. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: nasopharynx. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:16-22.

- Almomani MH, Zulfiqar H, Nagalli S. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC, lymphoepithelioma). StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Lassen CB, Lock-Andersen J. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with perineural invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:E252.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Pileri A, Facchetti F, Rütten A, et al. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare variant of the disease with peculiar clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:100-109.

- Ryu HJ, Kim SI, Jang HO, et al. Evaluation of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides [published October 15, 2021]. Cells. 2021;10:2758. doi:10.3390/cells10102758

- Lehmer LM, Amber KT, de Feraudy SM. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma enabling a histopathologic “sigh of relief.” Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:920-923.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Fisher JC, White RM, Hurd DS. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case of one patient presenting with two primary cutaneous neoplasms. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. 2015;33:40-41.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Yu R, Salama S, Alowami S. Cutaneous lymphadenoma: a rare case and brief review of a diagnostic pitfall. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5358.

- Monteagudo C, Fúnez R, Sánchez-Sendra B, et al. Cutaneous lymphadenoma is a distinct trichoblastoma-like lymphoepithelial tumor with diffuse androgen receptor immunoreactivity, Notch1 ligand in Reed-Sternberg-like Cells, and common EGFR somatic mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1382-1390.

- Stelow EB, Wenig BM. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: nasopharynx. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:16-22.

- Almomani MH, Zulfiqar H, Nagalli S. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC, lymphoepithelioma). StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Lassen CB, Lock-Andersen J. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with perineural invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:E252.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Pileri A, Facchetti F, Rütten A, et al. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare variant of the disease with peculiar clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:100-109.

- Ryu HJ, Kim SI, Jang HO, et al. Evaluation of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides [published October 15, 2021]. Cells. 2021;10:2758. doi:10.3390/cells10102758

- Lehmer LM, Amber KT, de Feraudy SM. Syringotropic mycosis fungoides: a rare form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma enabling a histopathologic “sigh of relief.” Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:920-923.

A 77-year-old man presented with a 1.2-cm dermal nodule on the left temple of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become tender and darker in color. An excision was performed and submitted for histologic examination. Additional immunohistochemistry staining for Epstein-Barr virus was negative.

Treatments for Hidradenitis Suppurativa Comorbidities Help With Pain Management

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has an unpredictable disease course and poses substantial therapeutic challenges. It carries an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality. It also is associated with comorbidities including mood disorders, tobacco smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, which can complicate its management and considerably affect patients’ quality of life (QOL).1 Hidradenitis suppurativa also disproportionately affects minority groups and has far-reaching inequities; for example, the condition has a notable economic impact on patients, including higher unemployment and disability rates, lower-paying jobs, less paid time off, and other indirect costs.2,3 Race can impact how pain itself is treated. In one study (N = 217), Black patients with extremity fractures presenting to anemergency department were significantly less likely to receive analgesia compared to White patients despite reporting similar pain (57% vs 74%, respectively; P = .01).4 In another study, Hispanic patients were 7-times less likely to be treated with opioids compared to non-Hispanic patients with long-bone fractures.5 Herein, we highlight pain management disparities in HS patients.

Treating HS Comorbidities Helps Improve Pain

Pain is reported by almost all HS patients and is the symptom most associated with QOL impairment.6,7 Pain in HS is multifactorial, with other symptoms and comorbidities affecting its severity. Treatment of acute flares often is painful and procedural, including intralesional steroid injections or incision and drainage.8 Algorithms for addressing pain through the treatment of comorbidities also have been developed.6 Although there are few studies on the medications that treat related comorbidities in HS, there is evidence of their benefits in similar diseases; for example, treating depression in patients with irritable bowel disease (IBD) improved pain perception, cognitive function, and sexual dysfunction.9

Depression exacerbates pain, and higher levels of depression have been observed in severe HS.10,11 Additionally, more than 80% of individuals with HS report tobacco smoking.1 Nicotine not only increases pain sensitivity and decreases pain tolerance but also worsens neuropathic, nociceptive, and psychosocial pain, as well as mood disorders and sleep disturbances.12 Given the higher prevalence of depression and smoking in HS patients and the impact on pain, addressing these comorbidities is crucial. Additionally, poor sleep amplifies pain sensitivity and affects neurologic pain modulation.13 Chronic pain also is associated with obesity and sleep dysfunction.14

Treatments Targeting Pain and Comorbidities

Treatments that target comorbidities and other symptoms of HS also may improve pain. Bupropion is a well-studied antidepressant and first-line option to aid in smoking cessation. It provides acute and chronic pain relief associated with IBD and may perform similarly in patients with HS.15-18 Bupropion also demonstrated dose-dependent weight reduction in obese and overweight individuals.19,20 Additionally, varenicline is a first-line option to aid in smoking cessation and can be combined with bupropion to increase long-term efficacy.21,22

Other antidepressants may alleviate HS pain. The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine are recommended for chronic pain in HS.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine are inexpensive and widely available antidepressants. Citalopram is as efficacious as duloxetine for chronic pain with fewer side effects.23 Paroxetine has been shown to improve pain and pruritus, QOL, and depression in patients with IBD.24 Benefits such as improved weight and sexual dysfunction also have been reported.25

Metformin is well studied in Black patients, and greater glycemic response supports its efficacy for diabetes as well as HS, which disproportionately affects individuals with skin of color.26 Metformin also targets other comorbidities of HS, such as improving insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome, acne vulgaris, weight loss, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular risk, and neuropsychologic conditions.27 Growing evidence supports the use of metformin as a new agent in chronic pain management, specifically for patients with HS.28,29

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a complex medical condition seen disproportionately in minority groups. Understanding common comorbidities as well as the biases associated with pain management will allow providers to treat HS patients more effectively. Dermatologists who see many HS patients should become more familiar with treating these associated comorbidities to provide patient care that is more holistic and effective.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Yang H, Mu F, et al. Impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on work loss, indirect costs and income. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:147-154. doi:10.1111/bjd.17101

- Udechukwu NS, Fleischer AB. Higher risk of care for hidradenitis suppurativa in African American and non-Hispanic patients in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2017;109:44-48. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.09.002

- Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, et al. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11-16. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0

- Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537-1539.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Matusiak Ł, Szcze˛ch J, Kaaz K, et al. Clinical characteristics of pruritus and pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:191-194. doi:10.2340/00015555-2815

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:220-229. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(96)00036-9

- Phan K, Huo YR, Smith SD. Hidradenitis suppurativa and psychiatric comorbidities, suicides and substance abuse: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:821. doi:10.21037/atm-20-1028

- Woo AK. Depression and anxiety in pain. Rev Pain. 2010;4:8-12. doi:10.1177/204946371000400103

- Iida H, Yamaguchi S, Goyagi T, et al. Consensus statement on smoking cessation in patients with pain. J Anesth. 2022;36:671-687. doi:10.1007/s00540-022-03097-w

- Krause AJ, Prather AA, Wager TD, et al. The pain of sleep loss: a brain characterization in humans. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2291-2300. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2408-18.2018

- Mundal I, Gråwe RW, Bjørngaard JH, et al. Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:213. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-213

- Aubin H-J. Tolerability and safety of sustained-release bupropion in the management of smoking cessation. Drugs. 2002;(62 suppl 2):45-52. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262002-00005

- Shah TH, Moradimehr A. Bupropion for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:333-336. doi:10.1177/1049909110361229

- Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:25-50. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.013

- Walker PW, Cole JO, Gardner EA, et al. Improvement in fluoxetine-associated sexual dysfunction in patients switched to bupropion. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:459-465.

- Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/bupropion ER (contrave): newly approved treatment option for chronic weight management in obese adults. P T. 2016;41:164-172.

- Anderson JW, Greenway FL, Fujioka K, et al. Bupropion SR enhances weight loss: a 48-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Obes Res. 2002;10:633-641. doi:10.1038/oby.2002.86

- Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. Prevention and treatment of tobacco use: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1030-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.036

- Singh D, Saadabadi A. Varenicline. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Mazza M, Mazza O, Pazzaglia C, et al. Escitalopram 20 mg versus duloxetine 60 mg for the treatment of chronic low back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1049-1052. doi:10.1517/14656561003730413

- Docherty MJ, Jones RCW, Wallace MS. Managing pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:592-601.

- Shrestha P, Fariba KA, Abdijadid S. Paroxetine. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Williams LK, Padhukasahasram B, Ahmedani BK, et al. Differing effects of metformin on glycemic control by race-ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3160-3168. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1539

- Sharma S, Mathur DK, Paliwal V, et al. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of acne in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a newer approach to acne therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:34-38.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:1. doi:10.5070/D35VW402NF

- Baeza-Flores GDC, Guzmán-Priego CG, Parra-Flores LI, et al. Metformin: a prospective alternative for the treatment of chronic pain. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:558474. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.558474

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has an unpredictable disease course and poses substantial therapeutic challenges. It carries an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality. It also is associated with comorbidities including mood disorders, tobacco smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, which can complicate its management and considerably affect patients’ quality of life (QOL).1 Hidradenitis suppurativa also disproportionately affects minority groups and has far-reaching inequities; for example, the condition has a notable economic impact on patients, including higher unemployment and disability rates, lower-paying jobs, less paid time off, and other indirect costs.2,3 Race can impact how pain itself is treated. In one study (N = 217), Black patients with extremity fractures presenting to anemergency department were significantly less likely to receive analgesia compared to White patients despite reporting similar pain (57% vs 74%, respectively; P = .01).4 In another study, Hispanic patients were 7-times less likely to be treated with opioids compared to non-Hispanic patients with long-bone fractures.5 Herein, we highlight pain management disparities in HS patients.

Treating HS Comorbidities Helps Improve Pain

Pain is reported by almost all HS patients and is the symptom most associated with QOL impairment.6,7 Pain in HS is multifactorial, with other symptoms and comorbidities affecting its severity. Treatment of acute flares often is painful and procedural, including intralesional steroid injections or incision and drainage.8 Algorithms for addressing pain through the treatment of comorbidities also have been developed.6 Although there are few studies on the medications that treat related comorbidities in HS, there is evidence of their benefits in similar diseases; for example, treating depression in patients with irritable bowel disease (IBD) improved pain perception, cognitive function, and sexual dysfunction.9

Depression exacerbates pain, and higher levels of depression have been observed in severe HS.10,11 Additionally, more than 80% of individuals with HS report tobacco smoking.1 Nicotine not only increases pain sensitivity and decreases pain tolerance but also worsens neuropathic, nociceptive, and psychosocial pain, as well as mood disorders and sleep disturbances.12 Given the higher prevalence of depression and smoking in HS patients and the impact on pain, addressing these comorbidities is crucial. Additionally, poor sleep amplifies pain sensitivity and affects neurologic pain modulation.13 Chronic pain also is associated with obesity and sleep dysfunction.14

Treatments Targeting Pain and Comorbidities

Treatments that target comorbidities and other symptoms of HS also may improve pain. Bupropion is a well-studied antidepressant and first-line option to aid in smoking cessation. It provides acute and chronic pain relief associated with IBD and may perform similarly in patients with HS.15-18 Bupropion also demonstrated dose-dependent weight reduction in obese and overweight individuals.19,20 Additionally, varenicline is a first-line option to aid in smoking cessation and can be combined with bupropion to increase long-term efficacy.21,22

Other antidepressants may alleviate HS pain. The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine are recommended for chronic pain in HS.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine are inexpensive and widely available antidepressants. Citalopram is as efficacious as duloxetine for chronic pain with fewer side effects.23 Paroxetine has been shown to improve pain and pruritus, QOL, and depression in patients with IBD.24 Benefits such as improved weight and sexual dysfunction also have been reported.25

Metformin is well studied in Black patients, and greater glycemic response supports its efficacy for diabetes as well as HS, which disproportionately affects individuals with skin of color.26 Metformin also targets other comorbidities of HS, such as improving insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome, acne vulgaris, weight loss, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular risk, and neuropsychologic conditions.27 Growing evidence supports the use of metformin as a new agent in chronic pain management, specifically for patients with HS.28,29

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a complex medical condition seen disproportionately in minority groups. Understanding common comorbidities as well as the biases associated with pain management will allow providers to treat HS patients more effectively. Dermatologists who see many HS patients should become more familiar with treating these associated comorbidities to provide patient care that is more holistic and effective.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has an unpredictable disease course and poses substantial therapeutic challenges. It carries an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality. It also is associated with comorbidities including mood disorders, tobacco smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, which can complicate its management and considerably affect patients’ quality of life (QOL).1 Hidradenitis suppurativa also disproportionately affects minority groups and has far-reaching inequities; for example, the condition has a notable economic impact on patients, including higher unemployment and disability rates, lower-paying jobs, less paid time off, and other indirect costs.2,3 Race can impact how pain itself is treated. In one study (N = 217), Black patients with extremity fractures presenting to anemergency department were significantly less likely to receive analgesia compared to White patients despite reporting similar pain (57% vs 74%, respectively; P = .01).4 In another study, Hispanic patients were 7-times less likely to be treated with opioids compared to non-Hispanic patients with long-bone fractures.5 Herein, we highlight pain management disparities in HS patients.

Treating HS Comorbidities Helps Improve Pain

Pain is reported by almost all HS patients and is the symptom most associated with QOL impairment.6,7 Pain in HS is multifactorial, with other symptoms and comorbidities affecting its severity. Treatment of acute flares often is painful and procedural, including intralesional steroid injections or incision and drainage.8 Algorithms for addressing pain through the treatment of comorbidities also have been developed.6 Although there are few studies on the medications that treat related comorbidities in HS, there is evidence of their benefits in similar diseases; for example, treating depression in patients with irritable bowel disease (IBD) improved pain perception, cognitive function, and sexual dysfunction.9

Depression exacerbates pain, and higher levels of depression have been observed in severe HS.10,11 Additionally, more than 80% of individuals with HS report tobacco smoking.1 Nicotine not only increases pain sensitivity and decreases pain tolerance but also worsens neuropathic, nociceptive, and psychosocial pain, as well as mood disorders and sleep disturbances.12 Given the higher prevalence of depression and smoking in HS patients and the impact on pain, addressing these comorbidities is crucial. Additionally, poor sleep amplifies pain sensitivity and affects neurologic pain modulation.13 Chronic pain also is associated with obesity and sleep dysfunction.14

Treatments Targeting Pain and Comorbidities

Treatments that target comorbidities and other symptoms of HS also may improve pain. Bupropion is a well-studied antidepressant and first-line option to aid in smoking cessation. It provides acute and chronic pain relief associated with IBD and may perform similarly in patients with HS.15-18 Bupropion also demonstrated dose-dependent weight reduction in obese and overweight individuals.19,20 Additionally, varenicline is a first-line option to aid in smoking cessation and can be combined with bupropion to increase long-term efficacy.21,22

Other antidepressants may alleviate HS pain. The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine are recommended for chronic pain in HS.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine are inexpensive and widely available antidepressants. Citalopram is as efficacious as duloxetine for chronic pain with fewer side effects.23 Paroxetine has been shown to improve pain and pruritus, QOL, and depression in patients with IBD.24 Benefits such as improved weight and sexual dysfunction also have been reported.25

Metformin is well studied in Black patients, and greater glycemic response supports its efficacy for diabetes as well as HS, which disproportionately affects individuals with skin of color.26 Metformin also targets other comorbidities of HS, such as improving insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome, acne vulgaris, weight loss, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular risk, and neuropsychologic conditions.27 Growing evidence supports the use of metformin as a new agent in chronic pain management, specifically for patients with HS.28,29

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a complex medical condition seen disproportionately in minority groups. Understanding common comorbidities as well as the biases associated with pain management will allow providers to treat HS patients more effectively. Dermatologists who see many HS patients should become more familiar with treating these associated comorbidities to provide patient care that is more holistic and effective.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Yang H, Mu F, et al. Impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on work loss, indirect costs and income. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:147-154. doi:10.1111/bjd.17101

- Udechukwu NS, Fleischer AB. Higher risk of care for hidradenitis suppurativa in African American and non-Hispanic patients in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2017;109:44-48. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.09.002

- Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, et al. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11-16. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0

- Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537-1539.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Matusiak Ł, Szcze˛ch J, Kaaz K, et al. Clinical characteristics of pruritus and pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:191-194. doi:10.2340/00015555-2815

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:220-229. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(96)00036-9

- Phan K, Huo YR, Smith SD. Hidradenitis suppurativa and psychiatric comorbidities, suicides and substance abuse: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:821. doi:10.21037/atm-20-1028

- Woo AK. Depression and anxiety in pain. Rev Pain. 2010;4:8-12. doi:10.1177/204946371000400103

- Iida H, Yamaguchi S, Goyagi T, et al. Consensus statement on smoking cessation in patients with pain. J Anesth. 2022;36:671-687. doi:10.1007/s00540-022-03097-w

- Krause AJ, Prather AA, Wager TD, et al. The pain of sleep loss: a brain characterization in humans. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2291-2300. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2408-18.2018

- Mundal I, Gråwe RW, Bjørngaard JH, et al. Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:213. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-213

- Aubin H-J. Tolerability and safety of sustained-release bupropion in the management of smoking cessation. Drugs. 2002;(62 suppl 2):45-52. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262002-00005

- Shah TH, Moradimehr A. Bupropion for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:333-336. doi:10.1177/1049909110361229

- Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:25-50. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.013

- Walker PW, Cole JO, Gardner EA, et al. Improvement in fluoxetine-associated sexual dysfunction in patients switched to bupropion. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:459-465.

- Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/bupropion ER (contrave): newly approved treatment option for chronic weight management in obese adults. P T. 2016;41:164-172.

- Anderson JW, Greenway FL, Fujioka K, et al. Bupropion SR enhances weight loss: a 48-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Obes Res. 2002;10:633-641. doi:10.1038/oby.2002.86

- Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. Prevention and treatment of tobacco use: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1030-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.036

- Singh D, Saadabadi A. Varenicline. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Mazza M, Mazza O, Pazzaglia C, et al. Escitalopram 20 mg versus duloxetine 60 mg for the treatment of chronic low back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1049-1052. doi:10.1517/14656561003730413

- Docherty MJ, Jones RCW, Wallace MS. Managing pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:592-601.

- Shrestha P, Fariba KA, Abdijadid S. Paroxetine. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Williams LK, Padhukasahasram B, Ahmedani BK, et al. Differing effects of metformin on glycemic control by race-ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3160-3168. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1539

- Sharma S, Mathur DK, Paliwal V, et al. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of acne in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a newer approach to acne therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:34-38.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:1. doi:10.5070/D35VW402NF

- Baeza-Flores GDC, Guzmán-Priego CG, Parra-Flores LI, et al. Metformin: a prospective alternative for the treatment of chronic pain. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:558474. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.558474

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Yang H, Mu F, et al. Impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on work loss, indirect costs and income. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:147-154. doi:10.1111/bjd.17101

- Udechukwu NS, Fleischer AB. Higher risk of care for hidradenitis suppurativa in African American and non-Hispanic patients in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2017;109:44-48. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.09.002

- Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, et al. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11-16. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0

- Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537-1539.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Matusiak Ł, Szcze˛ch J, Kaaz K, et al. Clinical characteristics of pruritus and pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:191-194. doi:10.2340/00015555-2815

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:220-229. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(96)00036-9

- Phan K, Huo YR, Smith SD. Hidradenitis suppurativa and psychiatric comorbidities, suicides and substance abuse: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:821. doi:10.21037/atm-20-1028

- Woo AK. Depression and anxiety in pain. Rev Pain. 2010;4:8-12. doi:10.1177/204946371000400103

- Iida H, Yamaguchi S, Goyagi T, et al. Consensus statement on smoking cessation in patients with pain. J Anesth. 2022;36:671-687. doi:10.1007/s00540-022-03097-w

- Krause AJ, Prather AA, Wager TD, et al. The pain of sleep loss: a brain characterization in humans. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2291-2300. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2408-18.2018

- Mundal I, Gråwe RW, Bjørngaard JH, et al. Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:213. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-213

- Aubin H-J. Tolerability and safety of sustained-release bupropion in the management of smoking cessation. Drugs. 2002;(62 suppl 2):45-52. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262002-00005

- Shah TH, Moradimehr A. Bupropion for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:333-336. doi:10.1177/1049909110361229

- Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:25-50. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.013

- Walker PW, Cole JO, Gardner EA, et al. Improvement in fluoxetine-associated sexual dysfunction in patients switched to bupropion. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:459-465.

- Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/bupropion ER (contrave): newly approved treatment option for chronic weight management in obese adults. P T. 2016;41:164-172.

- Anderson JW, Greenway FL, Fujioka K, et al. Bupropion SR enhances weight loss: a 48-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Obes Res. 2002;10:633-641. doi:10.1038/oby.2002.86

- Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. Prevention and treatment of tobacco use: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1030-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.036

- Singh D, Saadabadi A. Varenicline. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Mazza M, Mazza O, Pazzaglia C, et al. Escitalopram 20 mg versus duloxetine 60 mg for the treatment of chronic low back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1049-1052. doi:10.1517/14656561003730413

- Docherty MJ, Jones RCW, Wallace MS. Managing pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:592-601.

- Shrestha P, Fariba KA, Abdijadid S. Paroxetine. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Williams LK, Padhukasahasram B, Ahmedani BK, et al. Differing effects of metformin on glycemic control by race-ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3160-3168. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1539

- Sharma S, Mathur DK, Paliwal V, et al. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of acne in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a newer approach to acne therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:34-38.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:1. doi:10.5070/D35VW402NF

- Baeza-Flores GDC, Guzmán-Priego CG, Parra-Flores LI, et al. Metformin: a prospective alternative for the treatment of chronic pain. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:558474. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.558474