User login

How to Teach the Potassium Hydroxide Preparation: A Disappearing Clinical Art Form

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

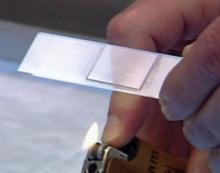

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

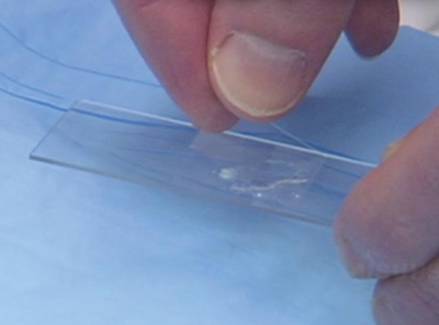

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

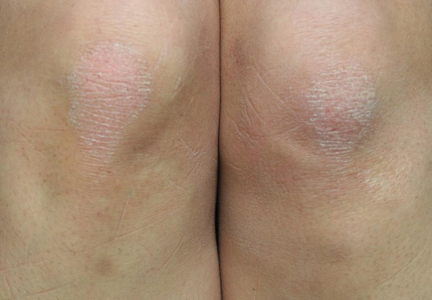

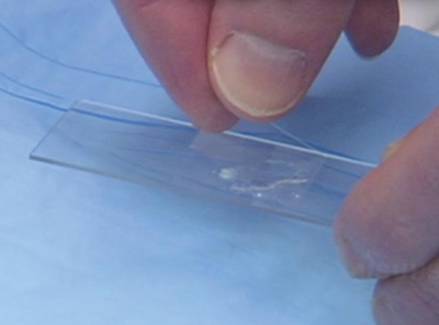

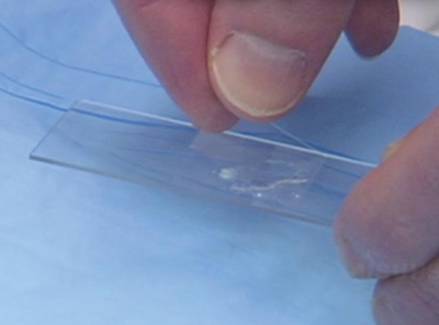

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

1. Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:238-242.

2. Stone S. Editor’s commentary. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:241-242.

3. Monroe JR. The diagnostic value of a KOH. JAAPA. 2001;4:50-51.

4. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;1:101-109.

5. Ponka D, Baddar F. Microscopic potassium hydroxide preparation. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:57.

6. Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;4:620-626.

7. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

9. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/. Updated June 6, 2015. Accessed July 21, 2015.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

1. Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:238-242.

2. Stone S. Editor’s commentary. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:241-242.

3. Monroe JR. The diagnostic value of a KOH. JAAPA. 2001;4:50-51.

4. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;1:101-109.

5. Ponka D, Baddar F. Microscopic potassium hydroxide preparation. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:57.

6. Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;4:620-626.

7. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

9. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/. Updated June 6, 2015. Accessed July 21, 2015.

1. Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:238-242.

2. Stone S. Editor’s commentary. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:241-242.

3. Monroe JR. The diagnostic value of a KOH. JAAPA. 2001;4:50-51.

4. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;1:101-109.

5. Ponka D, Baddar F. Microscopic potassium hydroxide preparation. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:57.

6. Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;4:620-626.

7. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

9. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/. Updated June 6, 2015. Accessed July 21, 2015.

Practice Points

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can lead to diagnostic confidence and direct appropriate therapy.

- Refreshing the basics of this simple technique can lead to better patient outcomes in the primary care setting and in the dermatology specialty clinic.

- Teaching the KOH preparation to the next generation of physicians will ensure its longevity and assure future benefit to patients.