User login

Which sling for which SUI patient?

- Placement of TVT-O transobturator tape

- Monarc transobturator procedure

- TVT Exact retropubic sling operation

These videos were selected by Mark D. Walters, MD, and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

Only 15 years ago, when surgery was recommended for patients who had bothersome stress urinary incontinence (SUI), they were offered operations such as suburethral (Kelly) plication, needle urethropexy, open or laparoscopic Burch procedure, and pubovaginal fascial sling procedure. Today, virtually all of these operations have been replaced in general practice by retropubic or transobturator (TOT) midurethral synthetic slings.

Although Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal fascial sling procedure are effective for both primary and recurrent SUI, they are more invasive than midurethral slings, cause more voiding dysfunction, and have significantly longer recovery times, making them less attractive for most primary and recurrent cases of SUI.

The evolution of SUI surgeries has shifted so far toward midurethral slings that Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal sling procedure are rarely performed or taught in obstetrics and gynecology or urology residency programs; these procedures are now mostly done in fellowship programs by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

In this article, we describe how an ObGyn generalist can approach the surgical treatment of women who have either primary or recurrent SUI. Using evidence-based principles, when available, we also discuss how different clinical characteristics—as well as the characteristics of the available slings—affect the suitability of the sling for individual patients.

One caveat: This article assumes that the surgeon knows how to, and is able to, perform retropubic and TOT sling procedures equally well. However, when this is not the case, the surgeon should perform the sling procedure that she or he does best, assuming that it is appropriate for that particular patient.

Almost all surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence performed today involve placement of a retropubic or transobturator midurethral synthetic sling.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

CASE: SUI and Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse

A healthy 45-year-old G2P2 woman complains of a 5-year history of worsening SUI symptoms, mostly occurring during activities such as coughing, laughing, and running. The incontinence has become so severe that she requires several pads daily. She is able to void without difficulty or pain, and her bowel movements are normal. She has regular menses, has had a tubal ligation, and is sexually active.

She reports that she has been performing daily Kegel pelvic muscle exercises, without improvement.

On physical examination, she is found to have Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse and urethral hypermobility, with normal uterine and posterior vaginal support. The uterus and ovaries are of normal size.

A full bladder stress test in the office reveals immediate loss of urine from the urethra upon coughing in a semi-sitting position. She voids 325 mL after the examination and has a post-void residual urine volume, as measured by ultrasonography (US), of 25 mL. Urinalysis is negative.

When discussing her goals, the patient expresses a desire for a cure of her urinary incontinence, if possible.

What further testing and treatment options do you offer to her?

If you and the patient agree that surgery is warranted, which procedure do you recommend?

Recommended assessment of women who report SUI

Women who have bothersome urine loss during activities such as exercise, coughing, or laughing should undergo a history, physical examination, and urinalysis. During the pelvic examination, it is important to assess pelvic organ support defects, especially those involving the anterior vagina and urethra. Also note levator ani muscle contraction and strength. In addition, you can use this time to discuss whether the patient is doing, or has done, pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises; teach the exercises, if necessary; and encourage her to do them in the future.

If the patient has no urinary infection, has performed Kegel exercises without further benefit, and wishes to consider surgical treatment, basic assessment of lower urinary function is indicated. Basic office urodynamic testing includes:

- a measured void

- measurement of post-void residual volume (by catheter or US)

- assessment of bladder sensation and capacity

- provocation for overactive bladder

- a full-bladder cough stress test (a positive test is direct observation of urethral loss of urine upon coughing).

Patients who have a complex history or mixed symptoms, previous failed surgery, or other characteristics that suggest a diagnosis other than simple SUI should undergo formal electronic urodynamic testing.1

Patient selection criteria

Primary sling surgery is an option for patients who have:

- no urinary infection

- normal voiding and bladder-filling function

- urethral hypermobility on examination

- SUI on a cough-stress test

- failure to improve sufficiently with pelvic muscle exercises.

Suburethral slings were initially developed as a treatment for recurrent, urodynamically confirmed SUI, particularly SUI caused by intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD). Pubovaginal slings, usually consisting of autologous fascia, were placed at the bladder neck to both support and slightly compress the proximal urethra. Compared with synthetic slings, fascial slings are effective but take longer to place and have a higher rate of surgical morbidity and more postoperative voiding dysfunction. They are now mostly indicated for complex recurrent SUI, usually managed by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Current slings are lightweight polypropylene mesh

Most slings today are tension-free midurethral slings consisting of synthetic, large-pore polypropylene mesh; they are sold in kits available from several different companies. Sling procedures can also be performed using hand-cut polypropylene mesh and a reusable needle passer.

These slings are placed at the midurethra and work by mechanical kinking or folding of the urethra over the sling, with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Ideally, the midurethral sling will not compress the urethra at rest and have no effect on the normal voiding mechanism.

Three main techniques are used to place synthetic midurethral slings:

- the retropubic approach

- the TOT approach

- variations of single-incision “mini-sling” procedures.

Early studies of mini-slings showed few complications but lower effectiveness, compared with retropubic and TOT midurethral slings, according to short-term follow-up data.2-4 A mini-sling might be an option for some patients in whom surgical complications must be kept to a minimum; otherwise, they will not be discussed further.

Retropubic midurethral slings

The tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure described by Petros and Ulmsten was the first synthetic midurethral sling.5 This ambulatory procedure aims to restore the pubourethral ligament and suburethral vaginal hammock by using specially designed needles attached to synthetic sling material.

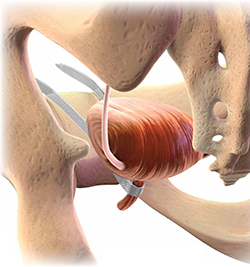

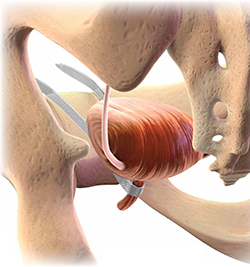

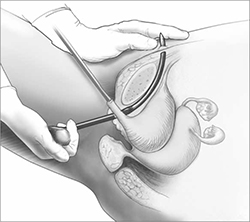

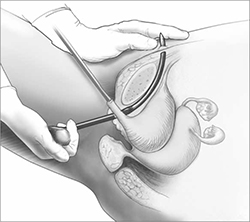

The synthetic sling consists of polypropylene, approximately 1 cm wide and 40 cm long. The sling material is attached to two stainless steel needles that are passed from a vaginal incision made at the level of the midurethra, through the retropubic space, and exiting at a previously created mark or stab incision in the suprapubic area (FIGURE 1).

Variations of the retropubic midurethral sling have been developed, with sling passers going from the vagina upward (“bottom to top”) and also from the suprapubic area downward (“top to bottom”). A recent Cochrane review reported that the bottom-to-top variation is slightly more effective.6

FIGURE 1 Retropubic sling

Placement of the tension-free vaginal tape trocar into the retropubic space.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

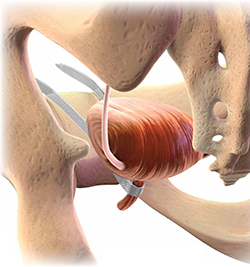

Transobturator midurethral slings

The TOT sling has become one of the most popular and effective surgical treatments for female SUI worldwide (Video 1 and Video 2). It is a relatively rapid and low-risk surgery that is comparable to other surgical options in effectiveness while avoiding an abdominal incision and the passage of a needle or trocar through the space of Retzius.

The TOT sling lies flatter under the urethra and carries a lower risk of urethral obstruction, urinary retention, and subsequent need for sling release, compared with retropubic slings.7-9 Compared with the retropubic TVT, the TOT sling produces similar rates of cure, with fewer bladder perforations and less postoperative irritative voiding symptoms.6,10-12 It nearly eliminates the rare but catastrophic risk of bowel or major vessel perforation. The trade-off is that patients experience more complications referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) with the TOT approach.9,13

All TOT slings on the market consist of a large-pore, lightweight, polypropylene mesh strip, usually covered with a plastic sheath. Various devices are used to place the sling, but most of them involve a helical trocar that curves around the ischiopubic ramus, passing through the inner thigh and obturator membrane to a space created in the ipsilateral peri-urethral tissues.

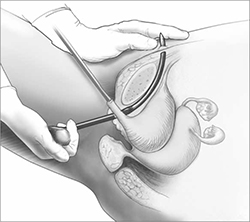

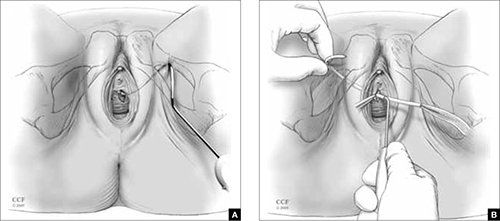

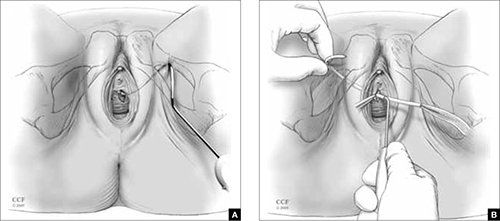

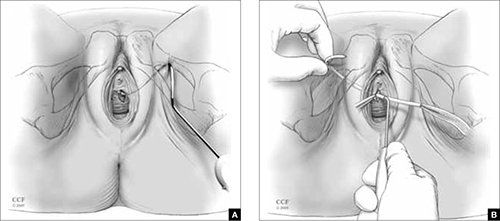

TOT slings can be placed outside-to-inside or inside-to-outside (FIGURE 2), and the indications, effectiveness, and frequency of complications seem to be similar between these two approaches.12 One study found a higher frequency of new sexual dysfunction (tender, palpable sling; penile pain in male partner) in women after the “outside-in” approach,14 but this clinical issue has not been observed in all studies.15,16

FIGURE 2 TOT sling variations

Placement of the transobturator (TOT) sling helical trocar using the (A) “outside-in” variation and (B) “inside-out” variation.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography

© 2005-2012. All Rights Reserved.

Success rates are similar for retropubic and TOT slings

Despite differences in technique and brand of mesh used, treatment success rates for uncomplicated primary SUI are similar for the retropubic (Video 3) and TOT tension-free slings.6-8,10-12,17 The percentage of patients treated successfully depends on the definition used, ranging from a high of 96% to a low of 60%. When the definition of success is restricted to stress incontinence symptoms, especially over a short period of time, the reported effectiveness is high.

In contrast, when the definition of success includes incontinence of any type, the reported effectiveness is lower. For example, in the study that reported 60% effectiveness, success was defined as no incontinence symptoms of any type, a negative cough stress test, and no retreatment for stress incontinence or postoperative urinary retention.11

Retropubic slings, especially TVT, may be somewhat more effective for ISD,18-20 although this conclusion must be tempered by the small number of studies addressing the issue and differences in the diagnosis of ISD.21

Some studies have reported good success in treating mixed urinary incontinence with the retropubic and TOT slings,2,8 although other studies have reported that the initial benefit for urgency or urge incontinence is not sustained over time, compared with the benefit for stress incontinence.22 It is important to counsel patients before surgery that improvement in stress incontinence symptoms and general satisfaction is highly likely, but perfect bladder function is not.

Serious complications are uncommon

Complications are common after both retropubic and TOT slings, although serious complications are uncommon. Cystitis and temporary voiding difficulties are the most common problems after a sling procedure. If the patient is unable to void on the day of surgery, it is reasonable to discharge her with a Foley catheter in place for a few days or teach her to perform intermittent self-catheterization at home. In most cases, normal voiding will resume within a few days. Cystitis is at least partially related to the surgery itself and the duration of postoperative catheterization.

The frequency of some complications differs between the retropubic and TOT approaches to midurethral slings. For example, some literature suggests that irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency or voiding difficulty are somewhat less common after TOT slings, compared with retropubic slings. However, symptoms referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) occur more commonly with the TOT approach.6

After placement of a TOT sling, 10% to 15% of women experience temporary inner thigh or groin pain or leg weakness and are usually managed conservatively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. Long-term or severe complications related to TOT sling passage are rare.

Major intraoperative complications are rare

The rate of these complications does not differ between retropubic and TOT approaches. Minor intraoperative complications—primarily, bladder perforation—occur more commonly with the retropubic approach.6

Bladder perforation with the TVT occurs in 4% to 7% of patients. However, the clinical significance of bladder perforation is minimal as long as the surgeon performs careful cystoscopy, recognizes bladder perforation, and repositions the trocar and mesh outside the bladder lumen. Bladder perforation caused by the trocar usually does not require specific treatment (except repositioning of the trocar outside the bladder lumen) and rarely results in later problems.

Mesh exposures occur with similar frequency for the different sling types as long as large-pore lightweight polypropylene is used. Dehiscence of the suburethral incision (mesh exposure) is uncommon with midurethral slings, occurring in 1% to 2% of patients. Dehiscence can be managed with estrogen cream or trimming of the exposed portion of the sling in the office. If symptoms or signs persist, removal of the exposed segment or the entire central portion of the sling, with closure of the vaginal epithelium, is indicated to allow for healing and resolution of symptoms. However, removal may lead to recurrence of the original SUI symptoms.

Retropubic hematomas occur in 1% to 2% of patients after placement of a retropubic sling, but major vascular injuries are rare—occurring in, perhaps, 3 in every 1,000 cases.

Bowel perforations are very rare but serious complications. A retropubic sling should be placed with caution or avoided in women who have a history of peritonitis, bowel surgery, ruptured appendix, or known extensive pelvic adhesions.

Major vascular injuries are also rare with TOT slings, occurring in approximately 1 to 2 cases in every 1,000.

Bladder injury occurs much less frequently after placement of a TOT sling, compared with the retropubic approach, although one study reported bladder injury in 2% of TOT cases.17 Although bladder injury is uncommon with the TOT approach, the morbidity associated with delayed detection of bladder injury is much higher than the morbidity associated with intraoperative detection and management. Therefore, we believe that cystoscopy should be performed in all TOT and retropubic sling procedures to either exclude bladder damage or detect and appropriately manage it.

For reassurance that intraoperative and postoperative blood loss is not excessive, it is reasonable to check one hemoglobin level before discharge, if desired.

How to individualize the choice of sling

Patients who have primary SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. Objective and subjective success rates are similar, regardless of approach, and serious complications are infrequent. The retropubic approach has longer-term evidence of sustained benefit, compared with the newer TOT approach. We tend to treat younger patients with TVT and older patients with TOT. Surgeon experience and informed patient preferences may dictate the choice of sling (TABLE).

What we recommend surgically for our patients who have SUI—and why

| Clinical problem and patient characteristics | Surgery | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—young patient | TVT | TVT has similar effectiveness and more long-term data than TOT; TVT may result in less sexual pain than TOT |

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—older patient; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TOT | Similar effectiveness, fewer complications with TOT |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—any age; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TVT | Limited data suggest effectiveness of TVT after TOT failure |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—leak point pressure <60 cmH20 (ISD) | TVT or pubovaginal fascial sling | Some but not all data indicate that TVT is more effective for ISD; fascial slings in expert hands are effective, based on cohort studies |

| Recurrent SUI with nonmobile bladder neck; any leak point pressure | Urethral bulking | All sling procedures have lowered effectiveness when the bladder neck is immobile |

| SUI mixed with dominant urgency or voiding dysfunction | TOT | TOT improves or does not exacerbate mixed urinary symptoms to the extent that TVT may |

| SUI with prolapse and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TVT or TOT | Limited data support similar effectiveness for either approach |

| “Occult” SUI with prolapse reduced and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TOT or “wait and see” | TOT has a lower chance of creating new irritative voiding symptoms; “wait-and-see” approach allows treatment of SUI if it develops after prolapse repair |

| Recurrent SUI with previous synthetic sling mesh complication (or patients who desire treatment without mesh) | Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension | These nonmesh options are effective for recurrent SUI, but have higher surgical morbidity |

| ISD = intrinsic sphincter deficiency; SUI = stress urinary incontinence; TVT = tension-free vaginal tape or similar retropubic midurethral sling; TOT = transobturator sling placed either by outside-in or inside-out variations | ||

Patients who have recurrent SUI: Retropubic sling. Comparative data are limited regarding the retropubic and TOT approaches for recurrent SUI that does not involve ISD. One case series reported good results with the use of retropubic TVT for recurrent SUI after an initial TOT approach.23

Patients who have ISD: Retropubic sling (synthetic midurethral sling or fascial sling placed at the bladder neck). A few studies suggest that patients with ISD have better outcomes with the retropubic approach.19,20 However, with differing definitions of ISD and relatively few patients with ISD included in these trials, it is not possible to conclude definitively that the retropubic approach is more effective than the TOT approach for patients who have SUI and ISD. However, the retropubic approach has longer-term data to support its effectiveness; therefore, with some but not all evidence suggesting its superiority for ISD, it is reasonable to choose the retropubic midurethral approach.

A pubovaginal fascial sling placed at the proximal urethra is also an effective option, based on numerous cohort studies.12

Patients who have recurrent SUI or ISD, or both, with a non-mobile bladder neck: Urethral bulking. Although data are scant, urethral injection therapy is beneficial for SUI in the short-term, but long-term studies are lacking. Bulking agents include silicone particles, calcium hydroxylapatite, and carbon spheres; studies have not shown one to be more or less efficacious than the others.24

It is reasonable to use urethral bulking first in these patients as the morbidity is very low and some patients become continent. A retropubic sling can be performed if urethral bulking fails to adequately improve symptoms, although the effectiveness is lower in this population than in women with SUI and urethral hypermobility.

Patients who have mixed stress and urge incontinence or voiding dysfunction: TOT sling. Limited data suggest that the TOT approach improves symptoms of mixed incontinence—or, at least, exacerbates them to a lesser degree than the retropubic approach. Rarely is a sling release needed to treat obstructive urinary symptoms after the TOT approach.

Patients who have prolapse and SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. When a sling procedure is performed at the same time as reconstructive surgery for prolapse, it has similar effectiveness, regardless of whether the retropubic or TOT approach is selected.8,11 A sling placed during prolapse surgery (placed through a separate midurethral incision) appears to be as effective as a sling placed as a sole procedure.

Patients who have prolapse and occult SUI: TOT sling. If you recommend a sling to prevent SUI after prolapse surgery by any route, pick the sling with acceptable efficacy and the lowest rates of complications and voiding dysfunction. Patients are especially intolerant of complications from a sling to prevent SUI. Given the ease of placement and low morbidity of a later outpatient sling procedure, it is also reasonable to offer patients the “wait-and-see” alternative to see if SUI develops after prolapse surgery and only then proceeding with sling surgery. In this way, overtreatment is avoided, and any complications that occur after sling surgery for SUI treatment may be better tolerated by the patient. The preferences of an informed patient may guide decisions in this setting.

Patients who have recurrent SUI with mesh complication: Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension. These non-mesh options are effective for recurrent SUI and can be performed at the same time as mesh removal. They carry higher surgical morbidity, longer operative time, and greater postoperative voiding dysfunction.

An informed patient can help guide the approach

The retropubic and TOT approaches to tension-free midurethral slings are similar in effectiveness. Most women experience significant improvement of SUI symptoms after sling placement, although many women continue to have some urinary symptoms.

Depending on their training, experience, and personal results—as well as the preferences of an informed patient—surgeons may recommend one approach over the other. In addition, certain clinical situations may favor one sling over another. Studies with longer-term follow-up in different patient subgroups are needed to adequately counsel women about the durability of results.

CASE: Resolved

After discussing the options with your patient, she opts to undergo anterior prolapse repair with concurrent placement of a TOT sling. The surgery is completed without complication. She is discharged later that day without a catheter after demonstrating normal voiding with low residual urine volume. Postoperatively, she reports mild pain referred to the groin. You instruct her to take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief. On her postoperative visit, she reports that the pain is gone and the SUI has almost completely resolved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #63: Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1533-1545.

2. Abdel-Fattah M, Ford JA, Lim CP, Madhuvrata P. Single-incision mini-slings versus standard midurethral slings in surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications. Eur Urol. 2011;60(3):468-480.

3. Hinoul P, Vervest HA, den Boon J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing an innovative single-incision sling with an established transobturator sling to treat female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2011;185(4):1356-1362.

4. Barber MD, Weidner AC, Sokol AI, et al. Foundation for Female Health Awareness Research Network. Single-incision mini-sling compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 pt 1):328-337.

5. Petros P, Ulmsten U. Intravaginal sling plasty (IVS): An ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary stress incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29(1):75-82.

6. Ogah J, Cody DJ, Rogerson L. Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women: a short version Cochrane review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(3):284-291.

7. Meschia M, Bertozzi R, Pifarotti P, et al. Perioperative morbidity and early results of a randomised trial comparing TVT and TVT-O. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(11):1257-1261.

8. Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2066-2076.

9. Brubaker L, Norton PA, Albo ME, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Adverse events over two years after retropubic or transobturator midurethral sling surgery: findings from the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(5):498.e1-6.

10. Sung VW, Schleinitz MD, Rardin CR, Ward RM, Myers DL. Comparison of retropubic vs transobturator approach to midurethral slings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):3-11.

11. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

12. Novara G, Artibani W, Barber MD, et al. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative data on colposuspensions, pubovaginal slings, and midurethral tapes in the surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2010;58(2):218-238.

13. Ross S, Robert M, Swaby C, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1287-1294.

14. Scheiner DA, Betschart C, Wiederkehr S, Seifert B, Fink D, Perucchini D. Twelve months effect on voiding function of retropubic compared with outside-in and inside-out transobturator midurethral slings. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(2):197-206.

15. De Souza A, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Sexual function following retropubic TVT and transobturator Monarc sling in women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency: a multicenter prospective study. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(2):153-158.

16. Sentilhes L, Berthier A, Loisel C, Descamps P, Marpeau L, Grise P. Female sexual function following surgery for stress urinary incontinence: tension-free vaginal versus transobturator tape procedure. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(4):393-399.

17. Deffieux X, Daher N, Mansoor A, Debodinance P, Muhlstein J, Fernandez H. Transobturator TVT-O versus retropubic TVT: results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial at 24 months follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(11):1337-1345.

18. Schierlitz L, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Effectiveness of tension-free vaginal tape compared with transobturator tape in women with stress urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1253-1261.

19. Rechberger T, Futyma K, Jankiewicz K, Adamiak A, Skorupski P. The clinical effectiveness of retropubic (IVS-02) and transobturator (IVS-04) midurethral slings: randomized trial. Eur Urol. 2009;56(1):24-30.

20. Schierlitz L, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia AN, et al. Three-year follow-up of tension-free vaginal tape compared with transobturator tape in women with stress urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 pt 1):321-327.

21. Nager C, Siris L, Litman HJ, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Baseline urodynamic predictors of treatment failure 1 year after midurethral sling surgery. J Urol. 2011;186(2):597-603.

22. Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(8):923-932.

23. Sabadell J, Poza JL, Esgueva A, Morales JC, Sanchez-Iglesias JL, Xercavins J. Usefulness of retropubic tape for recurrent stress incontinence after transobturator tape failure. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(12):1543-1547.

24. Kirchin V, Page T, Keegan PE, et al. Urethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; Feb 15;2:CD003881.-

- Placement of TVT-O transobturator tape

- Monarc transobturator procedure

- TVT Exact retropubic sling operation

These videos were selected by Mark D. Walters, MD, and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

Only 15 years ago, when surgery was recommended for patients who had bothersome stress urinary incontinence (SUI), they were offered operations such as suburethral (Kelly) plication, needle urethropexy, open or laparoscopic Burch procedure, and pubovaginal fascial sling procedure. Today, virtually all of these operations have been replaced in general practice by retropubic or transobturator (TOT) midurethral synthetic slings.

Although Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal fascial sling procedure are effective for both primary and recurrent SUI, they are more invasive than midurethral slings, cause more voiding dysfunction, and have significantly longer recovery times, making them less attractive for most primary and recurrent cases of SUI.

The evolution of SUI surgeries has shifted so far toward midurethral slings that Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal sling procedure are rarely performed or taught in obstetrics and gynecology or urology residency programs; these procedures are now mostly done in fellowship programs by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

In this article, we describe how an ObGyn generalist can approach the surgical treatment of women who have either primary or recurrent SUI. Using evidence-based principles, when available, we also discuss how different clinical characteristics—as well as the characteristics of the available slings—affect the suitability of the sling for individual patients.

One caveat: This article assumes that the surgeon knows how to, and is able to, perform retropubic and TOT sling procedures equally well. However, when this is not the case, the surgeon should perform the sling procedure that she or he does best, assuming that it is appropriate for that particular patient.

Almost all surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence performed today involve placement of a retropubic or transobturator midurethral synthetic sling.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

CASE: SUI and Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse

A healthy 45-year-old G2P2 woman complains of a 5-year history of worsening SUI symptoms, mostly occurring during activities such as coughing, laughing, and running. The incontinence has become so severe that she requires several pads daily. She is able to void without difficulty or pain, and her bowel movements are normal. She has regular menses, has had a tubal ligation, and is sexually active.

She reports that she has been performing daily Kegel pelvic muscle exercises, without improvement.

On physical examination, she is found to have Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse and urethral hypermobility, with normal uterine and posterior vaginal support. The uterus and ovaries are of normal size.

A full bladder stress test in the office reveals immediate loss of urine from the urethra upon coughing in a semi-sitting position. She voids 325 mL after the examination and has a post-void residual urine volume, as measured by ultrasonography (US), of 25 mL. Urinalysis is negative.

When discussing her goals, the patient expresses a desire for a cure of her urinary incontinence, if possible.

What further testing and treatment options do you offer to her?

If you and the patient agree that surgery is warranted, which procedure do you recommend?

Recommended assessment of women who report SUI

Women who have bothersome urine loss during activities such as exercise, coughing, or laughing should undergo a history, physical examination, and urinalysis. During the pelvic examination, it is important to assess pelvic organ support defects, especially those involving the anterior vagina and urethra. Also note levator ani muscle contraction and strength. In addition, you can use this time to discuss whether the patient is doing, or has done, pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises; teach the exercises, if necessary; and encourage her to do them in the future.

If the patient has no urinary infection, has performed Kegel exercises without further benefit, and wishes to consider surgical treatment, basic assessment of lower urinary function is indicated. Basic office urodynamic testing includes:

- a measured void

- measurement of post-void residual volume (by catheter or US)

- assessment of bladder sensation and capacity

- provocation for overactive bladder

- a full-bladder cough stress test (a positive test is direct observation of urethral loss of urine upon coughing).

Patients who have a complex history or mixed symptoms, previous failed surgery, or other characteristics that suggest a diagnosis other than simple SUI should undergo formal electronic urodynamic testing.1

Patient selection criteria

Primary sling surgery is an option for patients who have:

- no urinary infection

- normal voiding and bladder-filling function

- urethral hypermobility on examination

- SUI on a cough-stress test

- failure to improve sufficiently with pelvic muscle exercises.

Suburethral slings were initially developed as a treatment for recurrent, urodynamically confirmed SUI, particularly SUI caused by intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD). Pubovaginal slings, usually consisting of autologous fascia, were placed at the bladder neck to both support and slightly compress the proximal urethra. Compared with synthetic slings, fascial slings are effective but take longer to place and have a higher rate of surgical morbidity and more postoperative voiding dysfunction. They are now mostly indicated for complex recurrent SUI, usually managed by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Current slings are lightweight polypropylene mesh

Most slings today are tension-free midurethral slings consisting of synthetic, large-pore polypropylene mesh; they are sold in kits available from several different companies. Sling procedures can also be performed using hand-cut polypropylene mesh and a reusable needle passer.

These slings are placed at the midurethra and work by mechanical kinking or folding of the urethra over the sling, with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Ideally, the midurethral sling will not compress the urethra at rest and have no effect on the normal voiding mechanism.

Three main techniques are used to place synthetic midurethral slings:

- the retropubic approach

- the TOT approach

- variations of single-incision “mini-sling” procedures.

Early studies of mini-slings showed few complications but lower effectiveness, compared with retropubic and TOT midurethral slings, according to short-term follow-up data.2-4 A mini-sling might be an option for some patients in whom surgical complications must be kept to a minimum; otherwise, they will not be discussed further.

Retropubic midurethral slings

The tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure described by Petros and Ulmsten was the first synthetic midurethral sling.5 This ambulatory procedure aims to restore the pubourethral ligament and suburethral vaginal hammock by using specially designed needles attached to synthetic sling material.

The synthetic sling consists of polypropylene, approximately 1 cm wide and 40 cm long. The sling material is attached to two stainless steel needles that are passed from a vaginal incision made at the level of the midurethra, through the retropubic space, and exiting at a previously created mark or stab incision in the suprapubic area (FIGURE 1).

Variations of the retropubic midurethral sling have been developed, with sling passers going from the vagina upward (“bottom to top”) and also from the suprapubic area downward (“top to bottom”). A recent Cochrane review reported that the bottom-to-top variation is slightly more effective.6

FIGURE 1 Retropubic sling

Placement of the tension-free vaginal tape trocar into the retropubic space.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

Transobturator midurethral slings

The TOT sling has become one of the most popular and effective surgical treatments for female SUI worldwide (Video 1 and Video 2). It is a relatively rapid and low-risk surgery that is comparable to other surgical options in effectiveness while avoiding an abdominal incision and the passage of a needle or trocar through the space of Retzius.

The TOT sling lies flatter under the urethra and carries a lower risk of urethral obstruction, urinary retention, and subsequent need for sling release, compared with retropubic slings.7-9 Compared with the retropubic TVT, the TOT sling produces similar rates of cure, with fewer bladder perforations and less postoperative irritative voiding symptoms.6,10-12 It nearly eliminates the rare but catastrophic risk of bowel or major vessel perforation. The trade-off is that patients experience more complications referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) with the TOT approach.9,13

All TOT slings on the market consist of a large-pore, lightweight, polypropylene mesh strip, usually covered with a plastic sheath. Various devices are used to place the sling, but most of them involve a helical trocar that curves around the ischiopubic ramus, passing through the inner thigh and obturator membrane to a space created in the ipsilateral peri-urethral tissues.

TOT slings can be placed outside-to-inside or inside-to-outside (FIGURE 2), and the indications, effectiveness, and frequency of complications seem to be similar between these two approaches.12 One study found a higher frequency of new sexual dysfunction (tender, palpable sling; penile pain in male partner) in women after the “outside-in” approach,14 but this clinical issue has not been observed in all studies.15,16

FIGURE 2 TOT sling variations

Placement of the transobturator (TOT) sling helical trocar using the (A) “outside-in” variation and (B) “inside-out” variation.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography

© 2005-2012. All Rights Reserved.

Success rates are similar for retropubic and TOT slings

Despite differences in technique and brand of mesh used, treatment success rates for uncomplicated primary SUI are similar for the retropubic (Video 3) and TOT tension-free slings.6-8,10-12,17 The percentage of patients treated successfully depends on the definition used, ranging from a high of 96% to a low of 60%. When the definition of success is restricted to stress incontinence symptoms, especially over a short period of time, the reported effectiveness is high.

In contrast, when the definition of success includes incontinence of any type, the reported effectiveness is lower. For example, in the study that reported 60% effectiveness, success was defined as no incontinence symptoms of any type, a negative cough stress test, and no retreatment for stress incontinence or postoperative urinary retention.11

Retropubic slings, especially TVT, may be somewhat more effective for ISD,18-20 although this conclusion must be tempered by the small number of studies addressing the issue and differences in the diagnosis of ISD.21

Some studies have reported good success in treating mixed urinary incontinence with the retropubic and TOT slings,2,8 although other studies have reported that the initial benefit for urgency or urge incontinence is not sustained over time, compared with the benefit for stress incontinence.22 It is important to counsel patients before surgery that improvement in stress incontinence symptoms and general satisfaction is highly likely, but perfect bladder function is not.

Serious complications are uncommon

Complications are common after both retropubic and TOT slings, although serious complications are uncommon. Cystitis and temporary voiding difficulties are the most common problems after a sling procedure. If the patient is unable to void on the day of surgery, it is reasonable to discharge her with a Foley catheter in place for a few days or teach her to perform intermittent self-catheterization at home. In most cases, normal voiding will resume within a few days. Cystitis is at least partially related to the surgery itself and the duration of postoperative catheterization.

The frequency of some complications differs between the retropubic and TOT approaches to midurethral slings. For example, some literature suggests that irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency or voiding difficulty are somewhat less common after TOT slings, compared with retropubic slings. However, symptoms referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) occur more commonly with the TOT approach.6

After placement of a TOT sling, 10% to 15% of women experience temporary inner thigh or groin pain or leg weakness and are usually managed conservatively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. Long-term or severe complications related to TOT sling passage are rare.

Major intraoperative complications are rare

The rate of these complications does not differ between retropubic and TOT approaches. Minor intraoperative complications—primarily, bladder perforation—occur more commonly with the retropubic approach.6

Bladder perforation with the TVT occurs in 4% to 7% of patients. However, the clinical significance of bladder perforation is minimal as long as the surgeon performs careful cystoscopy, recognizes bladder perforation, and repositions the trocar and mesh outside the bladder lumen. Bladder perforation caused by the trocar usually does not require specific treatment (except repositioning of the trocar outside the bladder lumen) and rarely results in later problems.

Mesh exposures occur with similar frequency for the different sling types as long as large-pore lightweight polypropylene is used. Dehiscence of the suburethral incision (mesh exposure) is uncommon with midurethral slings, occurring in 1% to 2% of patients. Dehiscence can be managed with estrogen cream or trimming of the exposed portion of the sling in the office. If symptoms or signs persist, removal of the exposed segment or the entire central portion of the sling, with closure of the vaginal epithelium, is indicated to allow for healing and resolution of symptoms. However, removal may lead to recurrence of the original SUI symptoms.

Retropubic hematomas occur in 1% to 2% of patients after placement of a retropubic sling, but major vascular injuries are rare—occurring in, perhaps, 3 in every 1,000 cases.

Bowel perforations are very rare but serious complications. A retropubic sling should be placed with caution or avoided in women who have a history of peritonitis, bowel surgery, ruptured appendix, or known extensive pelvic adhesions.

Major vascular injuries are also rare with TOT slings, occurring in approximately 1 to 2 cases in every 1,000.

Bladder injury occurs much less frequently after placement of a TOT sling, compared with the retropubic approach, although one study reported bladder injury in 2% of TOT cases.17 Although bladder injury is uncommon with the TOT approach, the morbidity associated with delayed detection of bladder injury is much higher than the morbidity associated with intraoperative detection and management. Therefore, we believe that cystoscopy should be performed in all TOT and retropubic sling procedures to either exclude bladder damage or detect and appropriately manage it.

For reassurance that intraoperative and postoperative blood loss is not excessive, it is reasonable to check one hemoglobin level before discharge, if desired.

How to individualize the choice of sling

Patients who have primary SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. Objective and subjective success rates are similar, regardless of approach, and serious complications are infrequent. The retropubic approach has longer-term evidence of sustained benefit, compared with the newer TOT approach. We tend to treat younger patients with TVT and older patients with TOT. Surgeon experience and informed patient preferences may dictate the choice of sling (TABLE).

What we recommend surgically for our patients who have SUI—and why

| Clinical problem and patient characteristics | Surgery | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—young patient | TVT | TVT has similar effectiveness and more long-term data than TOT; TVT may result in less sexual pain than TOT |

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—older patient; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TOT | Similar effectiveness, fewer complications with TOT |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—any age; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TVT | Limited data suggest effectiveness of TVT after TOT failure |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—leak point pressure <60 cmH20 (ISD) | TVT or pubovaginal fascial sling | Some but not all data indicate that TVT is more effective for ISD; fascial slings in expert hands are effective, based on cohort studies |

| Recurrent SUI with nonmobile bladder neck; any leak point pressure | Urethral bulking | All sling procedures have lowered effectiveness when the bladder neck is immobile |

| SUI mixed with dominant urgency or voiding dysfunction | TOT | TOT improves or does not exacerbate mixed urinary symptoms to the extent that TVT may |

| SUI with prolapse and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TVT or TOT | Limited data support similar effectiveness for either approach |

| “Occult” SUI with prolapse reduced and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TOT or “wait and see” | TOT has a lower chance of creating new irritative voiding symptoms; “wait-and-see” approach allows treatment of SUI if it develops after prolapse repair |

| Recurrent SUI with previous synthetic sling mesh complication (or patients who desire treatment without mesh) | Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension | These nonmesh options are effective for recurrent SUI, but have higher surgical morbidity |

| ISD = intrinsic sphincter deficiency; SUI = stress urinary incontinence; TVT = tension-free vaginal tape or similar retropubic midurethral sling; TOT = transobturator sling placed either by outside-in or inside-out variations | ||

Patients who have recurrent SUI: Retropubic sling. Comparative data are limited regarding the retropubic and TOT approaches for recurrent SUI that does not involve ISD. One case series reported good results with the use of retropubic TVT for recurrent SUI after an initial TOT approach.23

Patients who have ISD: Retropubic sling (synthetic midurethral sling or fascial sling placed at the bladder neck). A few studies suggest that patients with ISD have better outcomes with the retropubic approach.19,20 However, with differing definitions of ISD and relatively few patients with ISD included in these trials, it is not possible to conclude definitively that the retropubic approach is more effective than the TOT approach for patients who have SUI and ISD. However, the retropubic approach has longer-term data to support its effectiveness; therefore, with some but not all evidence suggesting its superiority for ISD, it is reasonable to choose the retropubic midurethral approach.

A pubovaginal fascial sling placed at the proximal urethra is also an effective option, based on numerous cohort studies.12

Patients who have recurrent SUI or ISD, or both, with a non-mobile bladder neck: Urethral bulking. Although data are scant, urethral injection therapy is beneficial for SUI in the short-term, but long-term studies are lacking. Bulking agents include silicone particles, calcium hydroxylapatite, and carbon spheres; studies have not shown one to be more or less efficacious than the others.24

It is reasonable to use urethral bulking first in these patients as the morbidity is very low and some patients become continent. A retropubic sling can be performed if urethral bulking fails to adequately improve symptoms, although the effectiveness is lower in this population than in women with SUI and urethral hypermobility.

Patients who have mixed stress and urge incontinence or voiding dysfunction: TOT sling. Limited data suggest that the TOT approach improves symptoms of mixed incontinence—or, at least, exacerbates them to a lesser degree than the retropubic approach. Rarely is a sling release needed to treat obstructive urinary symptoms after the TOT approach.

Patients who have prolapse and SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. When a sling procedure is performed at the same time as reconstructive surgery for prolapse, it has similar effectiveness, regardless of whether the retropubic or TOT approach is selected.8,11 A sling placed during prolapse surgery (placed through a separate midurethral incision) appears to be as effective as a sling placed as a sole procedure.

Patients who have prolapse and occult SUI: TOT sling. If you recommend a sling to prevent SUI after prolapse surgery by any route, pick the sling with acceptable efficacy and the lowest rates of complications and voiding dysfunction. Patients are especially intolerant of complications from a sling to prevent SUI. Given the ease of placement and low morbidity of a later outpatient sling procedure, it is also reasonable to offer patients the “wait-and-see” alternative to see if SUI develops after prolapse surgery and only then proceeding with sling surgery. In this way, overtreatment is avoided, and any complications that occur after sling surgery for SUI treatment may be better tolerated by the patient. The preferences of an informed patient may guide decisions in this setting.

Patients who have recurrent SUI with mesh complication: Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension. These non-mesh options are effective for recurrent SUI and can be performed at the same time as mesh removal. They carry higher surgical morbidity, longer operative time, and greater postoperative voiding dysfunction.

An informed patient can help guide the approach

The retropubic and TOT approaches to tension-free midurethral slings are similar in effectiveness. Most women experience significant improvement of SUI symptoms after sling placement, although many women continue to have some urinary symptoms.

Depending on their training, experience, and personal results—as well as the preferences of an informed patient—surgeons may recommend one approach over the other. In addition, certain clinical situations may favor one sling over another. Studies with longer-term follow-up in different patient subgroups are needed to adequately counsel women about the durability of results.

CASE: Resolved

After discussing the options with your patient, she opts to undergo anterior prolapse repair with concurrent placement of a TOT sling. The surgery is completed without complication. She is discharged later that day without a catheter after demonstrating normal voiding with low residual urine volume. Postoperatively, she reports mild pain referred to the groin. You instruct her to take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief. On her postoperative visit, she reports that the pain is gone and the SUI has almost completely resolved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Placement of TVT-O transobturator tape

- Monarc transobturator procedure

- TVT Exact retropubic sling operation

These videos were selected by Mark D. Walters, MD, and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

Only 15 years ago, when surgery was recommended for patients who had bothersome stress urinary incontinence (SUI), they were offered operations such as suburethral (Kelly) plication, needle urethropexy, open or laparoscopic Burch procedure, and pubovaginal fascial sling procedure. Today, virtually all of these operations have been replaced in general practice by retropubic or transobturator (TOT) midurethral synthetic slings.

Although Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal fascial sling procedure are effective for both primary and recurrent SUI, they are more invasive than midurethral slings, cause more voiding dysfunction, and have significantly longer recovery times, making them less attractive for most primary and recurrent cases of SUI.

The evolution of SUI surgeries has shifted so far toward midurethral slings that Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal sling procedure are rarely performed or taught in obstetrics and gynecology or urology residency programs; these procedures are now mostly done in fellowship programs by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

In this article, we describe how an ObGyn generalist can approach the surgical treatment of women who have either primary or recurrent SUI. Using evidence-based principles, when available, we also discuss how different clinical characteristics—as well as the characteristics of the available slings—affect the suitability of the sling for individual patients.

One caveat: This article assumes that the surgeon knows how to, and is able to, perform retropubic and TOT sling procedures equally well. However, when this is not the case, the surgeon should perform the sling procedure that she or he does best, assuming that it is appropriate for that particular patient.

Almost all surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence performed today involve placement of a retropubic or transobturator midurethral synthetic sling.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

CASE: SUI and Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse

A healthy 45-year-old G2P2 woman complains of a 5-year history of worsening SUI symptoms, mostly occurring during activities such as coughing, laughing, and running. The incontinence has become so severe that she requires several pads daily. She is able to void without difficulty or pain, and her bowel movements are normal. She has regular menses, has had a tubal ligation, and is sexually active.

She reports that she has been performing daily Kegel pelvic muscle exercises, without improvement.

On physical examination, she is found to have Stage II anterior vaginal prolapse and urethral hypermobility, with normal uterine and posterior vaginal support. The uterus and ovaries are of normal size.

A full bladder stress test in the office reveals immediate loss of urine from the urethra upon coughing in a semi-sitting position. She voids 325 mL after the examination and has a post-void residual urine volume, as measured by ultrasonography (US), of 25 mL. Urinalysis is negative.

When discussing her goals, the patient expresses a desire for a cure of her urinary incontinence, if possible.

What further testing and treatment options do you offer to her?

If you and the patient agree that surgery is warranted, which procedure do you recommend?

Recommended assessment of women who report SUI

Women who have bothersome urine loss during activities such as exercise, coughing, or laughing should undergo a history, physical examination, and urinalysis. During the pelvic examination, it is important to assess pelvic organ support defects, especially those involving the anterior vagina and urethra. Also note levator ani muscle contraction and strength. In addition, you can use this time to discuss whether the patient is doing, or has done, pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises; teach the exercises, if necessary; and encourage her to do them in the future.

If the patient has no urinary infection, has performed Kegel exercises without further benefit, and wishes to consider surgical treatment, basic assessment of lower urinary function is indicated. Basic office urodynamic testing includes:

- a measured void

- measurement of post-void residual volume (by catheter or US)

- assessment of bladder sensation and capacity

- provocation for overactive bladder

- a full-bladder cough stress test (a positive test is direct observation of urethral loss of urine upon coughing).

Patients who have a complex history or mixed symptoms, previous failed surgery, or other characteristics that suggest a diagnosis other than simple SUI should undergo formal electronic urodynamic testing.1

Patient selection criteria

Primary sling surgery is an option for patients who have:

- no urinary infection

- normal voiding and bladder-filling function

- urethral hypermobility on examination

- SUI on a cough-stress test

- failure to improve sufficiently with pelvic muscle exercises.

Suburethral slings were initially developed as a treatment for recurrent, urodynamically confirmed SUI, particularly SUI caused by intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD). Pubovaginal slings, usually consisting of autologous fascia, were placed at the bladder neck to both support and slightly compress the proximal urethra. Compared with synthetic slings, fascial slings are effective but take longer to place and have a higher rate of surgical morbidity and more postoperative voiding dysfunction. They are now mostly indicated for complex recurrent SUI, usually managed by specialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Current slings are lightweight polypropylene mesh

Most slings today are tension-free midurethral slings consisting of synthetic, large-pore polypropylene mesh; they are sold in kits available from several different companies. Sling procedures can also be performed using hand-cut polypropylene mesh and a reusable needle passer.

These slings are placed at the midurethra and work by mechanical kinking or folding of the urethra over the sling, with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Ideally, the midurethral sling will not compress the urethra at rest and have no effect on the normal voiding mechanism.

Three main techniques are used to place synthetic midurethral slings:

- the retropubic approach

- the TOT approach

- variations of single-incision “mini-sling” procedures.

Early studies of mini-slings showed few complications but lower effectiveness, compared with retropubic and TOT midurethral slings, according to short-term follow-up data.2-4 A mini-sling might be an option for some patients in whom surgical complications must be kept to a minimum; otherwise, they will not be discussed further.

Retropubic midurethral slings

The tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure described by Petros and Ulmsten was the first synthetic midurethral sling.5 This ambulatory procedure aims to restore the pubourethral ligament and suburethral vaginal hammock by using specially designed needles attached to synthetic sling material.

The synthetic sling consists of polypropylene, approximately 1 cm wide and 40 cm long. The sling material is attached to two stainless steel needles that are passed from a vaginal incision made at the level of the midurethra, through the retropubic space, and exiting at a previously created mark or stab incision in the suprapubic area (FIGURE 1).

Variations of the retropubic midurethral sling have been developed, with sling passers going from the vagina upward (“bottom to top”) and also from the suprapubic area downward (“top to bottom”). A recent Cochrane review reported that the bottom-to-top variation is slightly more effective.6

FIGURE 1 Retropubic sling

Placement of the tension-free vaginal tape trocar into the retropubic space.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

Transobturator midurethral slings

The TOT sling has become one of the most popular and effective surgical treatments for female SUI worldwide (Video 1 and Video 2). It is a relatively rapid and low-risk surgery that is comparable to other surgical options in effectiveness while avoiding an abdominal incision and the passage of a needle or trocar through the space of Retzius.

The TOT sling lies flatter under the urethra and carries a lower risk of urethral obstruction, urinary retention, and subsequent need for sling release, compared with retropubic slings.7-9 Compared with the retropubic TVT, the TOT sling produces similar rates of cure, with fewer bladder perforations and less postoperative irritative voiding symptoms.6,10-12 It nearly eliminates the rare but catastrophic risk of bowel or major vessel perforation. The trade-off is that patients experience more complications referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) with the TOT approach.9,13

All TOT slings on the market consist of a large-pore, lightweight, polypropylene mesh strip, usually covered with a plastic sheath. Various devices are used to place the sling, but most of them involve a helical trocar that curves around the ischiopubic ramus, passing through the inner thigh and obturator membrane to a space created in the ipsilateral peri-urethral tissues.

TOT slings can be placed outside-to-inside or inside-to-outside (FIGURE 2), and the indications, effectiveness, and frequency of complications seem to be similar between these two approaches.12 One study found a higher frequency of new sexual dysfunction (tender, palpable sling; penile pain in male partner) in women after the “outside-in” approach,14 but this clinical issue has not been observed in all studies.15,16

FIGURE 2 TOT sling variations

Placement of the transobturator (TOT) sling helical trocar using the (A) “outside-in” variation and (B) “inside-out” variation.

Illustration: Craig Zuckerman for OBG Management

Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography

© 2005-2012. All Rights Reserved.

Success rates are similar for retropubic and TOT slings

Despite differences in technique and brand of mesh used, treatment success rates for uncomplicated primary SUI are similar for the retropubic (Video 3) and TOT tension-free slings.6-8,10-12,17 The percentage of patients treated successfully depends on the definition used, ranging from a high of 96% to a low of 60%. When the definition of success is restricted to stress incontinence symptoms, especially over a short period of time, the reported effectiveness is high.

In contrast, when the definition of success includes incontinence of any type, the reported effectiveness is lower. For example, in the study that reported 60% effectiveness, success was defined as no incontinence symptoms of any type, a negative cough stress test, and no retreatment for stress incontinence or postoperative urinary retention.11

Retropubic slings, especially TVT, may be somewhat more effective for ISD,18-20 although this conclusion must be tempered by the small number of studies addressing the issue and differences in the diagnosis of ISD.21

Some studies have reported good success in treating mixed urinary incontinence with the retropubic and TOT slings,2,8 although other studies have reported that the initial benefit for urgency or urge incontinence is not sustained over time, compared with the benefit for stress incontinence.22 It is important to counsel patients before surgery that improvement in stress incontinence symptoms and general satisfaction is highly likely, but perfect bladder function is not.

Serious complications are uncommon

Complications are common after both retropubic and TOT slings, although serious complications are uncommon. Cystitis and temporary voiding difficulties are the most common problems after a sling procedure. If the patient is unable to void on the day of surgery, it is reasonable to discharge her with a Foley catheter in place for a few days or teach her to perform intermittent self-catheterization at home. In most cases, normal voiding will resume within a few days. Cystitis is at least partially related to the surgery itself and the duration of postoperative catheterization.

The frequency of some complications differs between the retropubic and TOT approaches to midurethral slings. For example, some literature suggests that irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency or voiding difficulty are somewhat less common after TOT slings, compared with retropubic slings. However, symptoms referable to the groin (pain and leg weakness or numbness) occur more commonly with the TOT approach.6

After placement of a TOT sling, 10% to 15% of women experience temporary inner thigh or groin pain or leg weakness and are usually managed conservatively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. Long-term or severe complications related to TOT sling passage are rare.

Major intraoperative complications are rare

The rate of these complications does not differ between retropubic and TOT approaches. Minor intraoperative complications—primarily, bladder perforation—occur more commonly with the retropubic approach.6

Bladder perforation with the TVT occurs in 4% to 7% of patients. However, the clinical significance of bladder perforation is minimal as long as the surgeon performs careful cystoscopy, recognizes bladder perforation, and repositions the trocar and mesh outside the bladder lumen. Bladder perforation caused by the trocar usually does not require specific treatment (except repositioning of the trocar outside the bladder lumen) and rarely results in later problems.

Mesh exposures occur with similar frequency for the different sling types as long as large-pore lightweight polypropylene is used. Dehiscence of the suburethral incision (mesh exposure) is uncommon with midurethral slings, occurring in 1% to 2% of patients. Dehiscence can be managed with estrogen cream or trimming of the exposed portion of the sling in the office. If symptoms or signs persist, removal of the exposed segment or the entire central portion of the sling, with closure of the vaginal epithelium, is indicated to allow for healing and resolution of symptoms. However, removal may lead to recurrence of the original SUI symptoms.

Retropubic hematomas occur in 1% to 2% of patients after placement of a retropubic sling, but major vascular injuries are rare—occurring in, perhaps, 3 in every 1,000 cases.

Bowel perforations are very rare but serious complications. A retropubic sling should be placed with caution or avoided in women who have a history of peritonitis, bowel surgery, ruptured appendix, or known extensive pelvic adhesions.

Major vascular injuries are also rare with TOT slings, occurring in approximately 1 to 2 cases in every 1,000.

Bladder injury occurs much less frequently after placement of a TOT sling, compared with the retropubic approach, although one study reported bladder injury in 2% of TOT cases.17 Although bladder injury is uncommon with the TOT approach, the morbidity associated with delayed detection of bladder injury is much higher than the morbidity associated with intraoperative detection and management. Therefore, we believe that cystoscopy should be performed in all TOT and retropubic sling procedures to either exclude bladder damage or detect and appropriately manage it.

For reassurance that intraoperative and postoperative blood loss is not excessive, it is reasonable to check one hemoglobin level before discharge, if desired.

How to individualize the choice of sling

Patients who have primary SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. Objective and subjective success rates are similar, regardless of approach, and serious complications are infrequent. The retropubic approach has longer-term evidence of sustained benefit, compared with the newer TOT approach. We tend to treat younger patients with TVT and older patients with TOT. Surgeon experience and informed patient preferences may dictate the choice of sling (TABLE).

What we recommend surgically for our patients who have SUI—and why

| Clinical problem and patient characteristics | Surgery | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—young patient | TVT | TVT has similar effectiveness and more long-term data than TOT; TVT may result in less sexual pain than TOT |

| Primary SUI with urethral hypermobility—older patient; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TOT | Similar effectiveness, fewer complications with TOT |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—any age; leak point pressure >60 cmH20 | TVT | Limited data suggest effectiveness of TVT after TOT failure |

| Recurrent SUI with urethral hypermobility—leak point pressure <60 cmH20 (ISD) | TVT or pubovaginal fascial sling | Some but not all data indicate that TVT is more effective for ISD; fascial slings in expert hands are effective, based on cohort studies |

| Recurrent SUI with nonmobile bladder neck; any leak point pressure | Urethral bulking | All sling procedures have lowered effectiveness when the bladder neck is immobile |

| SUI mixed with dominant urgency or voiding dysfunction | TOT | TOT improves or does not exacerbate mixed urinary symptoms to the extent that TVT may |

| SUI with prolapse and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TVT or TOT | Limited data support similar effectiveness for either approach |

| “Occult” SUI with prolapse reduced and planned vaginal prolapse repair | TOT or “wait and see” | TOT has a lower chance of creating new irritative voiding symptoms; “wait-and-see” approach allows treatment of SUI if it develops after prolapse repair |

| Recurrent SUI with previous synthetic sling mesh complication (or patients who desire treatment without mesh) | Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension | These nonmesh options are effective for recurrent SUI, but have higher surgical morbidity |

| ISD = intrinsic sphincter deficiency; SUI = stress urinary incontinence; TVT = tension-free vaginal tape or similar retropubic midurethral sling; TOT = transobturator sling placed either by outside-in or inside-out variations | ||

Patients who have recurrent SUI: Retropubic sling. Comparative data are limited regarding the retropubic and TOT approaches for recurrent SUI that does not involve ISD. One case series reported good results with the use of retropubic TVT for recurrent SUI after an initial TOT approach.23

Patients who have ISD: Retropubic sling (synthetic midurethral sling or fascial sling placed at the bladder neck). A few studies suggest that patients with ISD have better outcomes with the retropubic approach.19,20 However, with differing definitions of ISD and relatively few patients with ISD included in these trials, it is not possible to conclude definitively that the retropubic approach is more effective than the TOT approach for patients who have SUI and ISD. However, the retropubic approach has longer-term data to support its effectiveness; therefore, with some but not all evidence suggesting its superiority for ISD, it is reasonable to choose the retropubic midurethral approach.

A pubovaginal fascial sling placed at the proximal urethra is also an effective option, based on numerous cohort studies.12

Patients who have recurrent SUI or ISD, or both, with a non-mobile bladder neck: Urethral bulking. Although data are scant, urethral injection therapy is beneficial for SUI in the short-term, but long-term studies are lacking. Bulking agents include silicone particles, calcium hydroxylapatite, and carbon spheres; studies have not shown one to be more or less efficacious than the others.24

It is reasonable to use urethral bulking first in these patients as the morbidity is very low and some patients become continent. A retropubic sling can be performed if urethral bulking fails to adequately improve symptoms, although the effectiveness is lower in this population than in women with SUI and urethral hypermobility.

Patients who have mixed stress and urge incontinence or voiding dysfunction: TOT sling. Limited data suggest that the TOT approach improves symptoms of mixed incontinence—or, at least, exacerbates them to a lesser degree than the retropubic approach. Rarely is a sling release needed to treat obstructive urinary symptoms after the TOT approach.

Patients who have prolapse and SUI: Retropubic or TOT sling. When a sling procedure is performed at the same time as reconstructive surgery for prolapse, it has similar effectiveness, regardless of whether the retropubic or TOT approach is selected.8,11 A sling placed during prolapse surgery (placed through a separate midurethral incision) appears to be as effective as a sling placed as a sole procedure.

Patients who have prolapse and occult SUI: TOT sling. If you recommend a sling to prevent SUI after prolapse surgery by any route, pick the sling with acceptable efficacy and the lowest rates of complications and voiding dysfunction. Patients are especially intolerant of complications from a sling to prevent SUI. Given the ease of placement and low morbidity of a later outpatient sling procedure, it is also reasonable to offer patients the “wait-and-see” alternative to see if SUI develops after prolapse surgery and only then proceeding with sling surgery. In this way, overtreatment is avoided, and any complications that occur after sling surgery for SUI treatment may be better tolerated by the patient. The preferences of an informed patient may guide decisions in this setting.

Patients who have recurrent SUI with mesh complication: Pubovaginal fascial sling or Burch colposuspension. These non-mesh options are effective for recurrent SUI and can be performed at the same time as mesh removal. They carry higher surgical morbidity, longer operative time, and greater postoperative voiding dysfunction.

An informed patient can help guide the approach

The retropubic and TOT approaches to tension-free midurethral slings are similar in effectiveness. Most women experience significant improvement of SUI symptoms after sling placement, although many women continue to have some urinary symptoms.

Depending on their training, experience, and personal results—as well as the preferences of an informed patient—surgeons may recommend one approach over the other. In addition, certain clinical situations may favor one sling over another. Studies with longer-term follow-up in different patient subgroups are needed to adequately counsel women about the durability of results.

CASE: Resolved

After discussing the options with your patient, she opts to undergo anterior prolapse repair with concurrent placement of a TOT sling. The surgery is completed without complication. She is discharged later that day without a catheter after demonstrating normal voiding with low residual urine volume. Postoperatively, she reports mild pain referred to the groin. You instruct her to take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief. On her postoperative visit, she reports that the pain is gone and the SUI has almost completely resolved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #63: Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1533-1545.

2. Abdel-Fattah M, Ford JA, Lim CP, Madhuvrata P. Single-incision mini-slings versus standard midurethral slings in surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications. Eur Urol. 2011;60(3):468-480.

3. Hinoul P, Vervest HA, den Boon J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing an innovative single-incision sling with an established transobturator sling to treat female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2011;185(4):1356-1362.

4. Barber MD, Weidner AC, Sokol AI, et al. Foundation for Female Health Awareness Research Network. Single-incision mini-sling compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 pt 1):328-337.

5. Petros P, Ulmsten U. Intravaginal sling plasty (IVS): An ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary stress incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29(1):75-82.

6. Ogah J, Cody DJ, Rogerson L. Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women: a short version Cochrane review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(3):284-291.

7. Meschia M, Bertozzi R, Pifarotti P, et al. Perioperative morbidity and early results of a randomised trial comparing TVT and TVT-O. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(11):1257-1261.

8. Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2066-2076.

9. Brubaker L, Norton PA, Albo ME, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Adverse events over two years after retropubic or transobturator midurethral sling surgery: findings from the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(5):498.e1-6.

10. Sung VW, Schleinitz MD, Rardin CR, Ward RM, Myers DL. Comparison of retropubic vs transobturator approach to midurethral slings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):3-11.

11. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

12. Novara G, Artibani W, Barber MD, et al. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative data on colposuspensions, pubovaginal slings, and midurethral tapes in the surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2010;58(2):218-238.

13. Ross S, Robert M, Swaby C, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1287-1294.