User login

Depressed and cognitively impaired

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

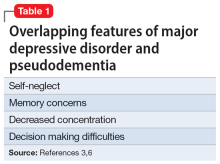

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

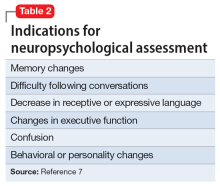

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53

Depressed and awkward: Is it more than that?

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

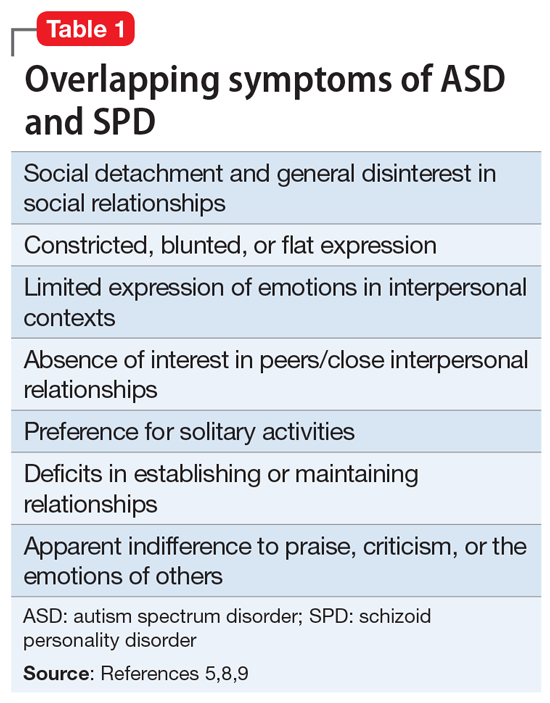

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

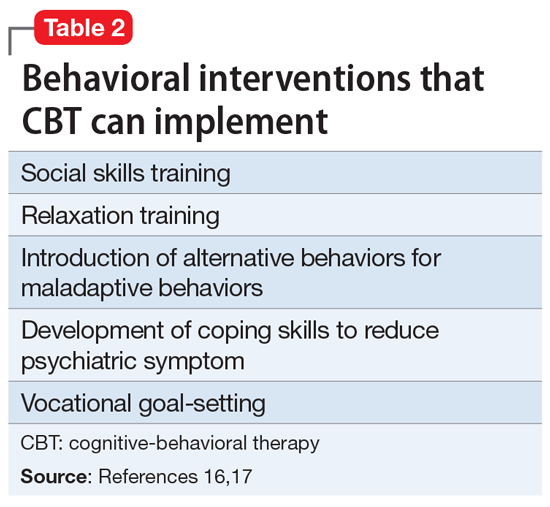

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

1. Fariba K, Gupta V. Schizoid personality disorder. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559234/

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed rev. American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

3. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(4):515-528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8

4. Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid personality disorder: a review of current status and implications for DSM-IV. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7(1), 43-52.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

7. Vatano

8. Ritsner MS. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances. Springer; 2011.

9. Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. On the continuity between autistic and schizoid personality disorder trait burden: a prospective study in adolescence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(2):94-100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

10. Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013-1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

11. Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, et al. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;10.1007/s00406-020-01189-2. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

12. Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

13. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, et al. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2389-2402. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

14. Giarelli E, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, et al. Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):107-116. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

15. Frazier TW, Georgiades S, Bishop SL, et al. Behavioral and cognitive characteristics of females and males with autism in the Simons Simplex Collection. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):329-40.e403. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.004

16. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA Jr, et al. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

17. Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;9, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019

18. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):687-694. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations