User login

So Much More than Bald and Bloated

A 44-year-old previously healthy semiprofessional male athlete presented with five days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had also experienced several months of decreased energy and new episodes of constipation three weeks prior to presentation.

At this point, we do not have sufficient information to completely determine the cause of his abdominal symptoms. Common causes of abdominal pain and vomiting in adults of his age group include peptic ulcer disease, pancreatic or hepatobiliary track disorders, small or large bowel processes, appendicitis, or even renal pathology. Further characterization may be possible by describing the location and quality of pain and factors that might relieve or exacerbate his pain. Despite the ambiguity, multiple clues might allow us to narrow the broad differential diagnosis of abdominal pain. In a previously healthy, vigorous, middle-aged man with subacute abdominal pain associated with constipation, the differential diagnosis should include disease states that may cause a bowel obstruction; these states include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), gastrointestinal malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease. Mechanical obstruction due to volvulus or intussusception would be less likely in his age group. Given his history of several months of fatigue and several weeks of constipation, he should be evaluated for metabolic causes of abdominal pain and constipation, such as hypothyroidism or hypercalcemia. In addition to basic laboratory and imaging studies, obtaining additional history regarding prior abdominal surgeries, medication use, alcohol intake, and family and travel history will be the key in directing the evaluation.

Six months prior to admission, the patient began to feel more fatigue and exercise intolerance, reduced sweating, increased cold intolerance, and increased presyncopal episodes. He was diagnosed with hypothyroidism (TSH 6.69 μIU/mL; free T4 not done) and initiated on levothyroxine. One month prior to presentation, he developed constipation, loss of taste, reduced appetite, and weight loss of 30 pounds. He developed blurry vision and photophobia. He also complained of erectile dysfunction, urinary hesitancy and straining, which were diagnosed as benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Given the addition of numerous historical features in a previously healthy man, it is important to strive for a parsimonious diagnosis to unify his seemingly disparate features. His fatigue, constipation, and cold intolerance are consistent with his diagnosis of hypothyroidism but are nonspecific. Whether the degree of hypothyroidism caused his symptoms or signs is doubtful. The constellation of symptoms and signs are more likely to be representative of a nonthyroidal illness. His abdominal pain, unexplained weight loss, and presyncopal episodes should raise consideration of adrenal insufficiency. The combination of hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency suggest the possibility of an autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome or other pituitary pathology. In this case, history of headache, dysgeusia, and visual disturbances might support the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma. A cosyntropin stimulation test could establish the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. A low ACTH level would establish a diagnosis of pituitary or hypothalamic hypofunction. If pituitary hypofunction is documented, then a brain MRI would be needed to confirm the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma.

His newly reported erectile dysfunction suggests the possibility of a psychiatric, neurologic, hormonal, or vascular process and should be explored further. Sexual dysfunction is also associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypopituitarism. However, the presence of suspected prostatic hypertrophy in a male competitive athlete in his forties also raises the question of exogenous androgen use.

His past medical history was notable for a two-year history of alopecia totalis, seasonal allergies, asthma, and a repaired congenital aortic web with known aortic insufficiency. He was married with two children, worked an office job, and had no history of injection drug use, blood transfusions, or multiple sexual partners. His family history was notable for hypothyroidism and asthma in several family members in addition to Crohn disease, celiac disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancers of the breast and lung.

His past medical, surgical, and family history supports a diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Although there is a personal and family history of atopic disorders, including allergic rhinitis and asthma, no association is found between atopy and autoimmunity. His family history of hypothyroidism, Crohn disease, and diabetes suggests a familial autoimmune genetic predisposition. His history of alopecia totalis in the setting of hypothyroidism and possible autoimmune adrenal insufficiency or autoimmune hypophysitis raises suspicion for the previously suggested diagnosis of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, also known as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. Type I polyglandular autoimmune syndrome is associated with hypoparathyroidism and mucocutaneous candidiasis. In the absence of these symptoms, the patient more likely has type II polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Type II syndrome is more prevalent and can occur in the setting of other nonendocrine autoimmune disorders, such as vitiligo, myasthenia gravis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Adrenal insufficiency can be the initial and most prominent manifestation of type II syndrome.

On physical exam, he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 68 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and normal oxygen saturation. His supine blood pressure and heart rate were 116/72 mm Hg and 66 beats per minute, respectively, and his standing blood pressure and heart rates were 80/48 mm Hg and 68 beats per minute respectively. He was thin, had diffuse scalp and body alopecia, and was ill-appearing with dry skin and dry mucous membranes. No evidence of Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, or splinter hemorrhages were found on cutaneous examination. No Roth spots or conjunctival hemorrhages were noted on ophthalmologic examination. He had both a 3/6 crescendo–decrescendo systolic murmur best heard at the right clavicle and radiated to the carotids and a 3/6 early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border. His abdomen was slightly protuberant, with reduced bowel sounds, hyperresonant to tympanitic on percussion, and a diffusely, moderately tender without peritoneal signs. Neurologic examination revealed 8 mm pupils with minimal response to light and accommodation. The remaining portions of his cranial nerve and complete neurologic examination were normal.

The presence of postural hypotension supports the previous suspicion of adrenal insufficiency, and the possibility of a pituitary or hypothalamic process remains. However, his dilated and minimally responsive pupils and potentially adynamic bowel are inconsistent with these diagnoses. Mydriasis and adynamic bowel in combination with orthostatic hypotension, dysgeusia, urinary retention, and erectile dysfunction are strongly suggestive of an autonomic process. Endocarditis is worth considering given his multisystem involvement, subacute decline, and known valve pathology. The absence of fever or stigmata of endocarditis make it difficult to explain his clinical syndrome. An echocardiogram would be reasonable for further assessment. At this point, it is prudent to explore his adrenal and pituitary function; if unrevealing, embark on an evaluation of his autonomic dysfunction.

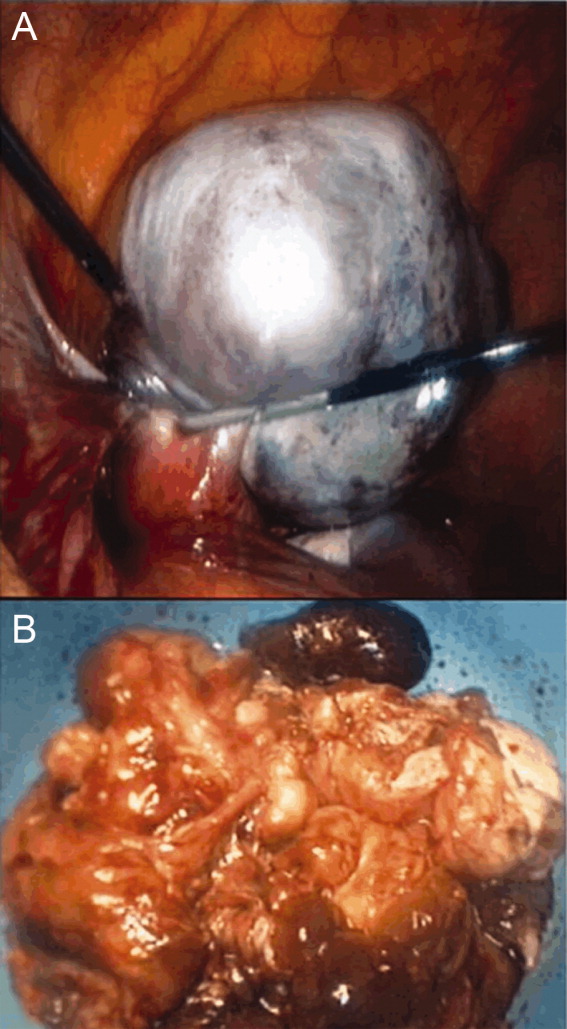

Initial laboratory investigations were notable for mild normocytic anemia and hypoalbuminemia. His cosyntropin stimulation test was normal at 60 minutes. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated marked dilation in the small bowel loops (6 cm in caliber) with associated small bowel wall thickening and hyperemia. The echocardiogram was unrevealing and only confirmed the ongoing, progression of his known valve pathology without evidence of vegetation.

The above testing rules out primary adrenal insufficiency, but an appropriate response to the cosyntropin stimulation test does not rule out secondary, or pituitary, adrenal insufficiency. The echocardiogram and lack of other features make infective endocarditis unlikely. Thus, as mentioned, it is important now to commence a complete work-up of his probable dysautonomia to explain the majority of his features. Additionally, his hypothyroidism (if more than sick euthyroid syndrome), family history of autoimmune processes, and alopecia totalis all suggest the possibility of an immune-related syndrome. His CT scan revealed some thickened hyperemic bowel, which could suggest an IBD, such as Crohn disease; however, the absence of other signs, such as fever, diarrhea, or bloody stools, argues against this diagnosis. A syndrome that could unify his presentation is autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), a rare genetic autonomic system disorder that presents with pandysautonomia. The spectrum of autoimmunity was considered early in this case, but the differential diagnosis included more common conditions, such as adrenal insufficiency. Similarly, IBD remains a consideration. The serologic studies for IBD can be useful but they lack definitive diagnostic accuracy. Given that treatment for AAG differs from that for IBD, additional information will help guide the therapeutic approach. Anti-α3gnAChR antibodies, which are associated with AAG, should be checked.

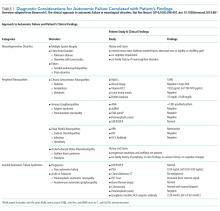

His history of presyncope, anhidrosis, urinary retention, and ileus raised suspicion for pandysautonomia, as characterized by signs of sympathetic and parasympathetic dysfunction. The suspicion for pandysautonomia was confirmed via specialized autonomic testing, which included reduced heart rate variation on Valsalva and deep breathing maneuvers, orthostatic hypotension consistent autonomic insufficiency on Tilt table testing, and reduced sweat response to acetylcholine application (QSART test). The patient underwent further diagnostic serologic testing to differentiate causes of autonomic failure (Table 1). His personal and family history of autoimmunity led to the working diagnosis of AAG. Ultimate testing revealed high titers of autoantibodies, specifically anti-α3gnAChR (3.29 nmol/L, normal <0.02 nmol/L), directed against the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This finding strongly supported the diagnosis of AAG.1,4-7

He was initially treated empirically with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with minimal improvement. He received additional immunomodulating therapies including methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and rituximab but did not tolerate a trial of mycophenolate. Six weeks after therapy initiation, his antibody titers decreased to 0.89 nmol/L with associated clinical improvement. Ultimately, he was discharged from the hospital on day 73 with a feeding tube and supplemental total parenteral nutrition. Four months postdischarge, he had returned to his prediagnosis weight, had eased back into his prior activities, and was off supplemental nutrition. Over a year later, he completed a 10-month prednisone taper and continued to receive monthly IVIG infusion

DISCUSSION

The clinical approach to dysautonomia is based on different etiologies: (1) those associated with neurodegenerative disorders; (2) those associated with peripheral neuropathies, and (3) isolated autonomic failure.2 Thus, clinical history and physical examination can assist greatly in guiding the evaluation of patients. Neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson disease), combined disorders (such as multiple-system atrophy), and acquired or familial processes were considered. Our patient had neither a personal or family history nor physical examination supporting a neurodegenerative disorder. Disorders of the peripheral nerves were considered and can broadly be categorized as chronic sensorimotor neuropathies, sensory ganglionopathies, distal painful neuropathies, and acute or subacute motor polyradiculopathies. During evaluation, no historical, physical examination, or laboratory findings supported diabetes, amyloidosis, heavy metals, Sjögren syndrome, paraneoplastic neuropathy, sodium channel disorders, infectious etiologies, or porphyria (Table 1). Thus, in the absence of supportive evidence for primary neurodegenerative disorders or peripheral neuropathies, his syndrome appeared most compatible with an isolated autonomic failure syndrome. The principal differential for this syndrome is pure autonomic failure versus an immune-mediated autonomic disorder, including paraneoplastic autoimmune neuropathy and AAG. The diagnosis of pure autonomic failure is made after there is no clear unifying syndrome after more than five years of investigation. After exploration, no evidence of malignancy was discovered on body cross sectional imaging, PET scanning, bone marrow biopsy, colonoscopy, or laboratory testing. Thus, positive serologic testing in the absence of an underlying malignancy suggests a diagnosis of AAG.

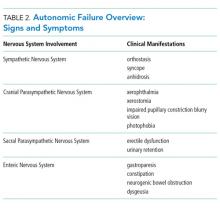

AAG was first described in 1969 and is a rare, acquired disorder characterized by combined failure of the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. This disorder typically presents in young-to-middle aged patients but has been described in all age groups. It is more commonly seen in patients with coexistent autoimmune diseases and/or a history of familial autoimmunity. The onset of clinical AAG may be subacute (less than three months) or insidious (more than three months). Patients present with signs or symptoms of pandysautonomia, such as severe orthostatic hypotension, syncope, constipation and gastrointestinal dysmotility, urinary retention, fixed and dilated pupils, and dry mouth and eyes (Table 2). Up to 40% of patients with AAG may also have significant cognitive impairment.3,4 Diagnosis relies on a combination of typical clinical features as discussed above and the exclusion of other diagnostic considerations. Diagnosis of AAG is aided by the presence of autoantibodies to ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (gnAChR), particularly antiganglionic acetylcholine receptor α3 (anti-α3gAChR).1 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are only present in about half of patients with AAG. Antibody titers are highest in subacute AAG (40%-50%)3 compared with chronic AAG (30%-40%) or paraneoplastic AAG (10%-20%).5 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are not specific to AAG and have been identified in low levels in up to 20% of patients with thymomas, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, chronic idiopathic anhidrosis, idiopathic gastrointestinal dysmotility, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, and myasthenia gravis without thymoma.1,5-7 These associations raise the question of shared pathology and perhaps a syndrome overlap. Individuals with seropositive AAG may also have other paraneoplastic antibodies, making it clinically indistinguishable from paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy.5,8 Although the autoantibody lacks sensitivity and is imperfectly specific, its presence supports a diagnosis of AAG. Anti-gnAChR antibodies have been shown to be pathological in rabbit and mouse models.4 In patients with AAG, higher autoantibody titers correlate with increased disease severity.1,6,7 A decrease in autoantibody titers correlates with decreased disease severity.6 Case report series also described a distinct entity of seronegative AAG.2,3 Maintaining a high clinical suspicion for AAG even with negative antibodies is important.

Given the rarity of the disease, no standard therapeutic regimens are available. About one-third of individuals improve on their own, while other individuals require extensive immunomodulation and symptom management. Case series and observational trials currently make up the vast array of treatment data. Therapies include glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, IVIG, and other immunosuppressive agents, such as rituximab.9-12 Patients with and without identified anti-gnAChRs antibodies may respond to therapy.12 The overall long-term prognosis of the disease is poorly characterized.9,10,13

Despite the rarity of the syndrome discussed, this case represents how diagnostic reasoning strategies, such as law of parsimony, shift how the case is framed. For example, a middle-aged man with several new, distinctly unrelated diagnoses versus a middle-aged man with signs and symptoms of autonomic failure alters the subsequent clinical reasoning and diagnostic approach. Many diseases, both common and rare, are associated with dysautonomia. Therefore, clinicians should have an approach to autonomic failure

TEACHING POINTS

- Recognize the following signs and symptoms suggesting a dysautonomic syndrome: orthostasis, syncope, anhidrosis, xerophthalmia, xerostomia, impaired pupillary constriction, blurry vision, photophobia, erectile dysfunction, urinary retention, gastroparesis, constipation, neurogenic bowel obstruction, and dysgeusia.

- Recognize the clinical features, diagnostic approach, and management of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.

- When faced with a complex clinical presentation, early application of the “law of parsimony” may help identify a unifying syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our Blinded Expert, Anthony Montanaro, MD, for his expertise and guidance during this process.

Disclosures

There are no known conflicts of interest.

1. Gibbons C, Freeman R. Antibody titers predict clinical features of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.013. PubMed

2. Golden E, Bryarly M, Vernino S. Seronegative autoimmune autonomic neuropathy: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Auton Res. 2018;28(1):115-123. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0493-8. PubMed

3. Sandroni P, Vernino S, Klein CM, et al. Idiopathic autonomic neuropathy: comparison of cases seropositive and seronegative for ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):44-48. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.44. PubMed

4. Vernino S, Ermilov L, Sha L, Szurszewski J, Low P, Lennon V. Passive transfer of autoimmune autonomic neuropathy to mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(32):7037-7042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1485-04.2004. PubMed

5. Vernino S, Hopkins S, Wang Z. Autonomic ganglia, acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and autoimmune ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):3-7. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.09.005. PubMed

6. Vernino S, Low P, Fealey R, Stewart J, Farrugia G, Lennon V. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):847-855. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009213431204. PubMed

7. Gibbons C, Vernino S, Freeman R. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy – Symptom antibody correlations. Auton Neurosci. 2015;192:130. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.07.241 .

8. Benarroch E. The clinical approach to autonomic failure in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(7):396-407. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.88. PubMed

9. Baker SK, Morillo C, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy with late-onset encephalopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.10.016. PubMed

10. Gibbons C, Centi J, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionoapthy with reversible cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(4):461-466. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2372. PubMed

11. Boydston E, Muppidi S, Vernino S. Long-term outcomes in autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P05.210). Neurology. 2012;78(1):P05.210. doi: 10.1212/WNL.78.1_MeetingAbstracts.P05.210.

12. Gehrking T, Sletten D, Fealey R, Low P, Singer W. 11-year follow-up of a case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P03.024). Neurology. 2013;80(7):P03.024.

13. Imrich R, Vernino S, Eldadah BA, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy: treatment by plasma exchanges and rituximab. Clin Auton Res. 2009;19(4):259-262. doi: 10.1007/s10286-009-0012-7. PubMed

14. Iodice V, Kimpinski K, Vernino S, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA. Efficacy of immunotherapy in seropositive and seronegative putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Neurology. 2009;72(23):2002-8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92b52. PubMed

15. Hayashi M, Ishii Y. A Japanese case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG) and a review of AAG cases in Japan. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):26-8. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.12.013. PubMed

16. Baker, A. Simplicity. In: Baker A, Zalta E, eds. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2016 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/simplicity/. Accessed October 26, 2017.

A 44-year-old previously healthy semiprofessional male athlete presented with five days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had also experienced several months of decreased energy and new episodes of constipation three weeks prior to presentation.

At this point, we do not have sufficient information to completely determine the cause of his abdominal symptoms. Common causes of abdominal pain and vomiting in adults of his age group include peptic ulcer disease, pancreatic or hepatobiliary track disorders, small or large bowel processes, appendicitis, or even renal pathology. Further characterization may be possible by describing the location and quality of pain and factors that might relieve or exacerbate his pain. Despite the ambiguity, multiple clues might allow us to narrow the broad differential diagnosis of abdominal pain. In a previously healthy, vigorous, middle-aged man with subacute abdominal pain associated with constipation, the differential diagnosis should include disease states that may cause a bowel obstruction; these states include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), gastrointestinal malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease. Mechanical obstruction due to volvulus or intussusception would be less likely in his age group. Given his history of several months of fatigue and several weeks of constipation, he should be evaluated for metabolic causes of abdominal pain and constipation, such as hypothyroidism or hypercalcemia. In addition to basic laboratory and imaging studies, obtaining additional history regarding prior abdominal surgeries, medication use, alcohol intake, and family and travel history will be the key in directing the evaluation.

Six months prior to admission, the patient began to feel more fatigue and exercise intolerance, reduced sweating, increased cold intolerance, and increased presyncopal episodes. He was diagnosed with hypothyroidism (TSH 6.69 μIU/mL; free T4 not done) and initiated on levothyroxine. One month prior to presentation, he developed constipation, loss of taste, reduced appetite, and weight loss of 30 pounds. He developed blurry vision and photophobia. He also complained of erectile dysfunction, urinary hesitancy and straining, which were diagnosed as benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Given the addition of numerous historical features in a previously healthy man, it is important to strive for a parsimonious diagnosis to unify his seemingly disparate features. His fatigue, constipation, and cold intolerance are consistent with his diagnosis of hypothyroidism but are nonspecific. Whether the degree of hypothyroidism caused his symptoms or signs is doubtful. The constellation of symptoms and signs are more likely to be representative of a nonthyroidal illness. His abdominal pain, unexplained weight loss, and presyncopal episodes should raise consideration of adrenal insufficiency. The combination of hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency suggest the possibility of an autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome or other pituitary pathology. In this case, history of headache, dysgeusia, and visual disturbances might support the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma. A cosyntropin stimulation test could establish the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. A low ACTH level would establish a diagnosis of pituitary or hypothalamic hypofunction. If pituitary hypofunction is documented, then a brain MRI would be needed to confirm the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma.

His newly reported erectile dysfunction suggests the possibility of a psychiatric, neurologic, hormonal, or vascular process and should be explored further. Sexual dysfunction is also associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypopituitarism. However, the presence of suspected prostatic hypertrophy in a male competitive athlete in his forties also raises the question of exogenous androgen use.

His past medical history was notable for a two-year history of alopecia totalis, seasonal allergies, asthma, and a repaired congenital aortic web with known aortic insufficiency. He was married with two children, worked an office job, and had no history of injection drug use, blood transfusions, or multiple sexual partners. His family history was notable for hypothyroidism and asthma in several family members in addition to Crohn disease, celiac disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancers of the breast and lung.

His past medical, surgical, and family history supports a diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Although there is a personal and family history of atopic disorders, including allergic rhinitis and asthma, no association is found between atopy and autoimmunity. His family history of hypothyroidism, Crohn disease, and diabetes suggests a familial autoimmune genetic predisposition. His history of alopecia totalis in the setting of hypothyroidism and possible autoimmune adrenal insufficiency or autoimmune hypophysitis raises suspicion for the previously suggested diagnosis of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, also known as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. Type I polyglandular autoimmune syndrome is associated with hypoparathyroidism and mucocutaneous candidiasis. In the absence of these symptoms, the patient more likely has type II polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Type II syndrome is more prevalent and can occur in the setting of other nonendocrine autoimmune disorders, such as vitiligo, myasthenia gravis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Adrenal insufficiency can be the initial and most prominent manifestation of type II syndrome.

On physical exam, he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 68 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and normal oxygen saturation. His supine blood pressure and heart rate were 116/72 mm Hg and 66 beats per minute, respectively, and his standing blood pressure and heart rates were 80/48 mm Hg and 68 beats per minute respectively. He was thin, had diffuse scalp and body alopecia, and was ill-appearing with dry skin and dry mucous membranes. No evidence of Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, or splinter hemorrhages were found on cutaneous examination. No Roth spots or conjunctival hemorrhages were noted on ophthalmologic examination. He had both a 3/6 crescendo–decrescendo systolic murmur best heard at the right clavicle and radiated to the carotids and a 3/6 early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border. His abdomen was slightly protuberant, with reduced bowel sounds, hyperresonant to tympanitic on percussion, and a diffusely, moderately tender without peritoneal signs. Neurologic examination revealed 8 mm pupils with minimal response to light and accommodation. The remaining portions of his cranial nerve and complete neurologic examination were normal.

The presence of postural hypotension supports the previous suspicion of adrenal insufficiency, and the possibility of a pituitary or hypothalamic process remains. However, his dilated and minimally responsive pupils and potentially adynamic bowel are inconsistent with these diagnoses. Mydriasis and adynamic bowel in combination with orthostatic hypotension, dysgeusia, urinary retention, and erectile dysfunction are strongly suggestive of an autonomic process. Endocarditis is worth considering given his multisystem involvement, subacute decline, and known valve pathology. The absence of fever or stigmata of endocarditis make it difficult to explain his clinical syndrome. An echocardiogram would be reasonable for further assessment. At this point, it is prudent to explore his adrenal and pituitary function; if unrevealing, embark on an evaluation of his autonomic dysfunction.

Initial laboratory investigations were notable for mild normocytic anemia and hypoalbuminemia. His cosyntropin stimulation test was normal at 60 minutes. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated marked dilation in the small bowel loops (6 cm in caliber) with associated small bowel wall thickening and hyperemia. The echocardiogram was unrevealing and only confirmed the ongoing, progression of his known valve pathology without evidence of vegetation.

The above testing rules out primary adrenal insufficiency, but an appropriate response to the cosyntropin stimulation test does not rule out secondary, or pituitary, adrenal insufficiency. The echocardiogram and lack of other features make infective endocarditis unlikely. Thus, as mentioned, it is important now to commence a complete work-up of his probable dysautonomia to explain the majority of his features. Additionally, his hypothyroidism (if more than sick euthyroid syndrome), family history of autoimmune processes, and alopecia totalis all suggest the possibility of an immune-related syndrome. His CT scan revealed some thickened hyperemic bowel, which could suggest an IBD, such as Crohn disease; however, the absence of other signs, such as fever, diarrhea, or bloody stools, argues against this diagnosis. A syndrome that could unify his presentation is autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), a rare genetic autonomic system disorder that presents with pandysautonomia. The spectrum of autoimmunity was considered early in this case, but the differential diagnosis included more common conditions, such as adrenal insufficiency. Similarly, IBD remains a consideration. The serologic studies for IBD can be useful but they lack definitive diagnostic accuracy. Given that treatment for AAG differs from that for IBD, additional information will help guide the therapeutic approach. Anti-α3gnAChR antibodies, which are associated with AAG, should be checked.

His history of presyncope, anhidrosis, urinary retention, and ileus raised suspicion for pandysautonomia, as characterized by signs of sympathetic and parasympathetic dysfunction. The suspicion for pandysautonomia was confirmed via specialized autonomic testing, which included reduced heart rate variation on Valsalva and deep breathing maneuvers, orthostatic hypotension consistent autonomic insufficiency on Tilt table testing, and reduced sweat response to acetylcholine application (QSART test). The patient underwent further diagnostic serologic testing to differentiate causes of autonomic failure (Table 1). His personal and family history of autoimmunity led to the working diagnosis of AAG. Ultimate testing revealed high titers of autoantibodies, specifically anti-α3gnAChR (3.29 nmol/L, normal <0.02 nmol/L), directed against the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This finding strongly supported the diagnosis of AAG.1,4-7

He was initially treated empirically with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with minimal improvement. He received additional immunomodulating therapies including methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and rituximab but did not tolerate a trial of mycophenolate. Six weeks after therapy initiation, his antibody titers decreased to 0.89 nmol/L with associated clinical improvement. Ultimately, he was discharged from the hospital on day 73 with a feeding tube and supplemental total parenteral nutrition. Four months postdischarge, he had returned to his prediagnosis weight, had eased back into his prior activities, and was off supplemental nutrition. Over a year later, he completed a 10-month prednisone taper and continued to receive monthly IVIG infusion

DISCUSSION

The clinical approach to dysautonomia is based on different etiologies: (1) those associated with neurodegenerative disorders; (2) those associated with peripheral neuropathies, and (3) isolated autonomic failure.2 Thus, clinical history and physical examination can assist greatly in guiding the evaluation of patients. Neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson disease), combined disorders (such as multiple-system atrophy), and acquired or familial processes were considered. Our patient had neither a personal or family history nor physical examination supporting a neurodegenerative disorder. Disorders of the peripheral nerves were considered and can broadly be categorized as chronic sensorimotor neuropathies, sensory ganglionopathies, distal painful neuropathies, and acute or subacute motor polyradiculopathies. During evaluation, no historical, physical examination, or laboratory findings supported diabetes, amyloidosis, heavy metals, Sjögren syndrome, paraneoplastic neuropathy, sodium channel disorders, infectious etiologies, or porphyria (Table 1). Thus, in the absence of supportive evidence for primary neurodegenerative disorders or peripheral neuropathies, his syndrome appeared most compatible with an isolated autonomic failure syndrome. The principal differential for this syndrome is pure autonomic failure versus an immune-mediated autonomic disorder, including paraneoplastic autoimmune neuropathy and AAG. The diagnosis of pure autonomic failure is made after there is no clear unifying syndrome after more than five years of investigation. After exploration, no evidence of malignancy was discovered on body cross sectional imaging, PET scanning, bone marrow biopsy, colonoscopy, or laboratory testing. Thus, positive serologic testing in the absence of an underlying malignancy suggests a diagnosis of AAG.

AAG was first described in 1969 and is a rare, acquired disorder characterized by combined failure of the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. This disorder typically presents in young-to-middle aged patients but has been described in all age groups. It is more commonly seen in patients with coexistent autoimmune diseases and/or a history of familial autoimmunity. The onset of clinical AAG may be subacute (less than three months) or insidious (more than three months). Patients present with signs or symptoms of pandysautonomia, such as severe orthostatic hypotension, syncope, constipation and gastrointestinal dysmotility, urinary retention, fixed and dilated pupils, and dry mouth and eyes (Table 2). Up to 40% of patients with AAG may also have significant cognitive impairment.3,4 Diagnosis relies on a combination of typical clinical features as discussed above and the exclusion of other diagnostic considerations. Diagnosis of AAG is aided by the presence of autoantibodies to ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (gnAChR), particularly antiganglionic acetylcholine receptor α3 (anti-α3gAChR).1 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are only present in about half of patients with AAG. Antibody titers are highest in subacute AAG (40%-50%)3 compared with chronic AAG (30%-40%) or paraneoplastic AAG (10%-20%).5 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are not specific to AAG and have been identified in low levels in up to 20% of patients with thymomas, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, chronic idiopathic anhidrosis, idiopathic gastrointestinal dysmotility, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, and myasthenia gravis without thymoma.1,5-7 These associations raise the question of shared pathology and perhaps a syndrome overlap. Individuals with seropositive AAG may also have other paraneoplastic antibodies, making it clinically indistinguishable from paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy.5,8 Although the autoantibody lacks sensitivity and is imperfectly specific, its presence supports a diagnosis of AAG. Anti-gnAChR antibodies have been shown to be pathological in rabbit and mouse models.4 In patients with AAG, higher autoantibody titers correlate with increased disease severity.1,6,7 A decrease in autoantibody titers correlates with decreased disease severity.6 Case report series also described a distinct entity of seronegative AAG.2,3 Maintaining a high clinical suspicion for AAG even with negative antibodies is important.

Given the rarity of the disease, no standard therapeutic regimens are available. About one-third of individuals improve on their own, while other individuals require extensive immunomodulation and symptom management. Case series and observational trials currently make up the vast array of treatment data. Therapies include glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, IVIG, and other immunosuppressive agents, such as rituximab.9-12 Patients with and without identified anti-gnAChRs antibodies may respond to therapy.12 The overall long-term prognosis of the disease is poorly characterized.9,10,13

Despite the rarity of the syndrome discussed, this case represents how diagnostic reasoning strategies, such as law of parsimony, shift how the case is framed. For example, a middle-aged man with several new, distinctly unrelated diagnoses versus a middle-aged man with signs and symptoms of autonomic failure alters the subsequent clinical reasoning and diagnostic approach. Many diseases, both common and rare, are associated with dysautonomia. Therefore, clinicians should have an approach to autonomic failure

TEACHING POINTS

- Recognize the following signs and symptoms suggesting a dysautonomic syndrome: orthostasis, syncope, anhidrosis, xerophthalmia, xerostomia, impaired pupillary constriction, blurry vision, photophobia, erectile dysfunction, urinary retention, gastroparesis, constipation, neurogenic bowel obstruction, and dysgeusia.

- Recognize the clinical features, diagnostic approach, and management of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.

- When faced with a complex clinical presentation, early application of the “law of parsimony” may help identify a unifying syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our Blinded Expert, Anthony Montanaro, MD, for his expertise and guidance during this process.

Disclosures

There are no known conflicts of interest.

A 44-year-old previously healthy semiprofessional male athlete presented with five days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had also experienced several months of decreased energy and new episodes of constipation three weeks prior to presentation.

At this point, we do not have sufficient information to completely determine the cause of his abdominal symptoms. Common causes of abdominal pain and vomiting in adults of his age group include peptic ulcer disease, pancreatic or hepatobiliary track disorders, small or large bowel processes, appendicitis, or even renal pathology. Further characterization may be possible by describing the location and quality of pain and factors that might relieve or exacerbate his pain. Despite the ambiguity, multiple clues might allow us to narrow the broad differential diagnosis of abdominal pain. In a previously healthy, vigorous, middle-aged man with subacute abdominal pain associated with constipation, the differential diagnosis should include disease states that may cause a bowel obstruction; these states include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), gastrointestinal malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease. Mechanical obstruction due to volvulus or intussusception would be less likely in his age group. Given his history of several months of fatigue and several weeks of constipation, he should be evaluated for metabolic causes of abdominal pain and constipation, such as hypothyroidism or hypercalcemia. In addition to basic laboratory and imaging studies, obtaining additional history regarding prior abdominal surgeries, medication use, alcohol intake, and family and travel history will be the key in directing the evaluation.

Six months prior to admission, the patient began to feel more fatigue and exercise intolerance, reduced sweating, increased cold intolerance, and increased presyncopal episodes. He was diagnosed with hypothyroidism (TSH 6.69 μIU/mL; free T4 not done) and initiated on levothyroxine. One month prior to presentation, he developed constipation, loss of taste, reduced appetite, and weight loss of 30 pounds. He developed blurry vision and photophobia. He also complained of erectile dysfunction, urinary hesitancy and straining, which were diagnosed as benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Given the addition of numerous historical features in a previously healthy man, it is important to strive for a parsimonious diagnosis to unify his seemingly disparate features. His fatigue, constipation, and cold intolerance are consistent with his diagnosis of hypothyroidism but are nonspecific. Whether the degree of hypothyroidism caused his symptoms or signs is doubtful. The constellation of symptoms and signs are more likely to be representative of a nonthyroidal illness. His abdominal pain, unexplained weight loss, and presyncopal episodes should raise consideration of adrenal insufficiency. The combination of hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency suggest the possibility of an autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome or other pituitary pathology. In this case, history of headache, dysgeusia, and visual disturbances might support the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma. A cosyntropin stimulation test could establish the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. A low ACTH level would establish a diagnosis of pituitary or hypothalamic hypofunction. If pituitary hypofunction is documented, then a brain MRI would be needed to confirm the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma.

His newly reported erectile dysfunction suggests the possibility of a psychiatric, neurologic, hormonal, or vascular process and should be explored further. Sexual dysfunction is also associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypopituitarism. However, the presence of suspected prostatic hypertrophy in a male competitive athlete in his forties also raises the question of exogenous androgen use.

His past medical history was notable for a two-year history of alopecia totalis, seasonal allergies, asthma, and a repaired congenital aortic web with known aortic insufficiency. He was married with two children, worked an office job, and had no history of injection drug use, blood transfusions, or multiple sexual partners. His family history was notable for hypothyroidism and asthma in several family members in addition to Crohn disease, celiac disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancers of the breast and lung.

His past medical, surgical, and family history supports a diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Although there is a personal and family history of atopic disorders, including allergic rhinitis and asthma, no association is found between atopy and autoimmunity. His family history of hypothyroidism, Crohn disease, and diabetes suggests a familial autoimmune genetic predisposition. His history of alopecia totalis in the setting of hypothyroidism and possible autoimmune adrenal insufficiency or autoimmune hypophysitis raises suspicion for the previously suggested diagnosis of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, also known as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. Type I polyglandular autoimmune syndrome is associated with hypoparathyroidism and mucocutaneous candidiasis. In the absence of these symptoms, the patient more likely has type II polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Type II syndrome is more prevalent and can occur in the setting of other nonendocrine autoimmune disorders, such as vitiligo, myasthenia gravis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Adrenal insufficiency can be the initial and most prominent manifestation of type II syndrome.

On physical exam, he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 68 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and normal oxygen saturation. His supine blood pressure and heart rate were 116/72 mm Hg and 66 beats per minute, respectively, and his standing blood pressure and heart rates were 80/48 mm Hg and 68 beats per minute respectively. He was thin, had diffuse scalp and body alopecia, and was ill-appearing with dry skin and dry mucous membranes. No evidence of Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, or splinter hemorrhages were found on cutaneous examination. No Roth spots or conjunctival hemorrhages were noted on ophthalmologic examination. He had both a 3/6 crescendo–decrescendo systolic murmur best heard at the right clavicle and radiated to the carotids and a 3/6 early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border. His abdomen was slightly protuberant, with reduced bowel sounds, hyperresonant to tympanitic on percussion, and a diffusely, moderately tender without peritoneal signs. Neurologic examination revealed 8 mm pupils with minimal response to light and accommodation. The remaining portions of his cranial nerve and complete neurologic examination were normal.

The presence of postural hypotension supports the previous suspicion of adrenal insufficiency, and the possibility of a pituitary or hypothalamic process remains. However, his dilated and minimally responsive pupils and potentially adynamic bowel are inconsistent with these diagnoses. Mydriasis and adynamic bowel in combination with orthostatic hypotension, dysgeusia, urinary retention, and erectile dysfunction are strongly suggestive of an autonomic process. Endocarditis is worth considering given his multisystem involvement, subacute decline, and known valve pathology. The absence of fever or stigmata of endocarditis make it difficult to explain his clinical syndrome. An echocardiogram would be reasonable for further assessment. At this point, it is prudent to explore his adrenal and pituitary function; if unrevealing, embark on an evaluation of his autonomic dysfunction.

Initial laboratory investigations were notable for mild normocytic anemia and hypoalbuminemia. His cosyntropin stimulation test was normal at 60 minutes. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated marked dilation in the small bowel loops (6 cm in caliber) with associated small bowel wall thickening and hyperemia. The echocardiogram was unrevealing and only confirmed the ongoing, progression of his known valve pathology without evidence of vegetation.

The above testing rules out primary adrenal insufficiency, but an appropriate response to the cosyntropin stimulation test does not rule out secondary, or pituitary, adrenal insufficiency. The echocardiogram and lack of other features make infective endocarditis unlikely. Thus, as mentioned, it is important now to commence a complete work-up of his probable dysautonomia to explain the majority of his features. Additionally, his hypothyroidism (if more than sick euthyroid syndrome), family history of autoimmune processes, and alopecia totalis all suggest the possibility of an immune-related syndrome. His CT scan revealed some thickened hyperemic bowel, which could suggest an IBD, such as Crohn disease; however, the absence of other signs, such as fever, diarrhea, or bloody stools, argues against this diagnosis. A syndrome that could unify his presentation is autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), a rare genetic autonomic system disorder that presents with pandysautonomia. The spectrum of autoimmunity was considered early in this case, but the differential diagnosis included more common conditions, such as adrenal insufficiency. Similarly, IBD remains a consideration. The serologic studies for IBD can be useful but they lack definitive diagnostic accuracy. Given that treatment for AAG differs from that for IBD, additional information will help guide the therapeutic approach. Anti-α3gnAChR antibodies, which are associated with AAG, should be checked.

His history of presyncope, anhidrosis, urinary retention, and ileus raised suspicion for pandysautonomia, as characterized by signs of sympathetic and parasympathetic dysfunction. The suspicion for pandysautonomia was confirmed via specialized autonomic testing, which included reduced heart rate variation on Valsalva and deep breathing maneuvers, orthostatic hypotension consistent autonomic insufficiency on Tilt table testing, and reduced sweat response to acetylcholine application (QSART test). The patient underwent further diagnostic serologic testing to differentiate causes of autonomic failure (Table 1). His personal and family history of autoimmunity led to the working diagnosis of AAG. Ultimate testing revealed high titers of autoantibodies, specifically anti-α3gnAChR (3.29 nmol/L, normal <0.02 nmol/L), directed against the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This finding strongly supported the diagnosis of AAG.1,4-7

He was initially treated empirically with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with minimal improvement. He received additional immunomodulating therapies including methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and rituximab but did not tolerate a trial of mycophenolate. Six weeks after therapy initiation, his antibody titers decreased to 0.89 nmol/L with associated clinical improvement. Ultimately, he was discharged from the hospital on day 73 with a feeding tube and supplemental total parenteral nutrition. Four months postdischarge, he had returned to his prediagnosis weight, had eased back into his prior activities, and was off supplemental nutrition. Over a year later, he completed a 10-month prednisone taper and continued to receive monthly IVIG infusion

DISCUSSION

The clinical approach to dysautonomia is based on different etiologies: (1) those associated with neurodegenerative disorders; (2) those associated with peripheral neuropathies, and (3) isolated autonomic failure.2 Thus, clinical history and physical examination can assist greatly in guiding the evaluation of patients. Neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson disease), combined disorders (such as multiple-system atrophy), and acquired or familial processes were considered. Our patient had neither a personal or family history nor physical examination supporting a neurodegenerative disorder. Disorders of the peripheral nerves were considered and can broadly be categorized as chronic sensorimotor neuropathies, sensory ganglionopathies, distal painful neuropathies, and acute or subacute motor polyradiculopathies. During evaluation, no historical, physical examination, or laboratory findings supported diabetes, amyloidosis, heavy metals, Sjögren syndrome, paraneoplastic neuropathy, sodium channel disorders, infectious etiologies, or porphyria (Table 1). Thus, in the absence of supportive evidence for primary neurodegenerative disorders or peripheral neuropathies, his syndrome appeared most compatible with an isolated autonomic failure syndrome. The principal differential for this syndrome is pure autonomic failure versus an immune-mediated autonomic disorder, including paraneoplastic autoimmune neuropathy and AAG. The diagnosis of pure autonomic failure is made after there is no clear unifying syndrome after more than five years of investigation. After exploration, no evidence of malignancy was discovered on body cross sectional imaging, PET scanning, bone marrow biopsy, colonoscopy, or laboratory testing. Thus, positive serologic testing in the absence of an underlying malignancy suggests a diagnosis of AAG.

AAG was first described in 1969 and is a rare, acquired disorder characterized by combined failure of the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. This disorder typically presents in young-to-middle aged patients but has been described in all age groups. It is more commonly seen in patients with coexistent autoimmune diseases and/or a history of familial autoimmunity. The onset of clinical AAG may be subacute (less than three months) or insidious (more than three months). Patients present with signs or symptoms of pandysautonomia, such as severe orthostatic hypotension, syncope, constipation and gastrointestinal dysmotility, urinary retention, fixed and dilated pupils, and dry mouth and eyes (Table 2). Up to 40% of patients with AAG may also have significant cognitive impairment.3,4 Diagnosis relies on a combination of typical clinical features as discussed above and the exclusion of other diagnostic considerations. Diagnosis of AAG is aided by the presence of autoantibodies to ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (gnAChR), particularly antiganglionic acetylcholine receptor α3 (anti-α3gAChR).1 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are only present in about half of patients with AAG. Antibody titers are highest in subacute AAG (40%-50%)3 compared with chronic AAG (30%-40%) or paraneoplastic AAG (10%-20%).5 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are not specific to AAG and have been identified in low levels in up to 20% of patients with thymomas, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, chronic idiopathic anhidrosis, idiopathic gastrointestinal dysmotility, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, and myasthenia gravis without thymoma.1,5-7 These associations raise the question of shared pathology and perhaps a syndrome overlap. Individuals with seropositive AAG may also have other paraneoplastic antibodies, making it clinically indistinguishable from paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy.5,8 Although the autoantibody lacks sensitivity and is imperfectly specific, its presence supports a diagnosis of AAG. Anti-gnAChR antibodies have been shown to be pathological in rabbit and mouse models.4 In patients with AAG, higher autoantibody titers correlate with increased disease severity.1,6,7 A decrease in autoantibody titers correlates with decreased disease severity.6 Case report series also described a distinct entity of seronegative AAG.2,3 Maintaining a high clinical suspicion for AAG even with negative antibodies is important.

Given the rarity of the disease, no standard therapeutic regimens are available. About one-third of individuals improve on their own, while other individuals require extensive immunomodulation and symptom management. Case series and observational trials currently make up the vast array of treatment data. Therapies include glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, IVIG, and other immunosuppressive agents, such as rituximab.9-12 Patients with and without identified anti-gnAChRs antibodies may respond to therapy.12 The overall long-term prognosis of the disease is poorly characterized.9,10,13

Despite the rarity of the syndrome discussed, this case represents how diagnostic reasoning strategies, such as law of parsimony, shift how the case is framed. For example, a middle-aged man with several new, distinctly unrelated diagnoses versus a middle-aged man with signs and symptoms of autonomic failure alters the subsequent clinical reasoning and diagnostic approach. Many diseases, both common and rare, are associated with dysautonomia. Therefore, clinicians should have an approach to autonomic failure

TEACHING POINTS

- Recognize the following signs and symptoms suggesting a dysautonomic syndrome: orthostasis, syncope, anhidrosis, xerophthalmia, xerostomia, impaired pupillary constriction, blurry vision, photophobia, erectile dysfunction, urinary retention, gastroparesis, constipation, neurogenic bowel obstruction, and dysgeusia.

- Recognize the clinical features, diagnostic approach, and management of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.

- When faced with a complex clinical presentation, early application of the “law of parsimony” may help identify a unifying syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our Blinded Expert, Anthony Montanaro, MD, for his expertise and guidance during this process.

Disclosures

There are no known conflicts of interest.

1. Gibbons C, Freeman R. Antibody titers predict clinical features of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.013. PubMed

2. Golden E, Bryarly M, Vernino S. Seronegative autoimmune autonomic neuropathy: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Auton Res. 2018;28(1):115-123. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0493-8. PubMed

3. Sandroni P, Vernino S, Klein CM, et al. Idiopathic autonomic neuropathy: comparison of cases seropositive and seronegative for ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):44-48. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.44. PubMed

4. Vernino S, Ermilov L, Sha L, Szurszewski J, Low P, Lennon V. Passive transfer of autoimmune autonomic neuropathy to mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(32):7037-7042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1485-04.2004. PubMed

5. Vernino S, Hopkins S, Wang Z. Autonomic ganglia, acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and autoimmune ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):3-7. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.09.005. PubMed

6. Vernino S, Low P, Fealey R, Stewart J, Farrugia G, Lennon V. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):847-855. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009213431204. PubMed

7. Gibbons C, Vernino S, Freeman R. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy – Symptom antibody correlations. Auton Neurosci. 2015;192:130. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.07.241 .

8. Benarroch E. The clinical approach to autonomic failure in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(7):396-407. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.88. PubMed

9. Baker SK, Morillo C, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy with late-onset encephalopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.10.016. PubMed

10. Gibbons C, Centi J, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionoapthy with reversible cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(4):461-466. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2372. PubMed

11. Boydston E, Muppidi S, Vernino S. Long-term outcomes in autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P05.210). Neurology. 2012;78(1):P05.210. doi: 10.1212/WNL.78.1_MeetingAbstracts.P05.210.

12. Gehrking T, Sletten D, Fealey R, Low P, Singer W. 11-year follow-up of a case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P03.024). Neurology. 2013;80(7):P03.024.

13. Imrich R, Vernino S, Eldadah BA, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy: treatment by plasma exchanges and rituximab. Clin Auton Res. 2009;19(4):259-262. doi: 10.1007/s10286-009-0012-7. PubMed

14. Iodice V, Kimpinski K, Vernino S, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA. Efficacy of immunotherapy in seropositive and seronegative putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Neurology. 2009;72(23):2002-8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92b52. PubMed

15. Hayashi M, Ishii Y. A Japanese case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG) and a review of AAG cases in Japan. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):26-8. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.12.013. PubMed

16. Baker, A. Simplicity. In: Baker A, Zalta E, eds. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2016 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/simplicity/. Accessed October 26, 2017.

1. Gibbons C, Freeman R. Antibody titers predict clinical features of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.013. PubMed

2. Golden E, Bryarly M, Vernino S. Seronegative autoimmune autonomic neuropathy: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Auton Res. 2018;28(1):115-123. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0493-8. PubMed

3. Sandroni P, Vernino S, Klein CM, et al. Idiopathic autonomic neuropathy: comparison of cases seropositive and seronegative for ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):44-48. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.44. PubMed

4. Vernino S, Ermilov L, Sha L, Szurszewski J, Low P, Lennon V. Passive transfer of autoimmune autonomic neuropathy to mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(32):7037-7042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1485-04.2004. PubMed

5. Vernino S, Hopkins S, Wang Z. Autonomic ganglia, acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and autoimmune ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):3-7. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.09.005. PubMed

6. Vernino S, Low P, Fealey R, Stewart J, Farrugia G, Lennon V. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):847-855. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009213431204. PubMed

7. Gibbons C, Vernino S, Freeman R. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy – Symptom antibody correlations. Auton Neurosci. 2015;192:130. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.07.241 .

8. Benarroch E. The clinical approach to autonomic failure in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(7):396-407. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.88. PubMed

9. Baker SK, Morillo C, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy with late-onset encephalopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.10.016. PubMed

10. Gibbons C, Centi J, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionoapthy with reversible cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(4):461-466. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2372. PubMed

11. Boydston E, Muppidi S, Vernino S. Long-term outcomes in autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P05.210). Neurology. 2012;78(1):P05.210. doi: 10.1212/WNL.78.1_MeetingAbstracts.P05.210.

12. Gehrking T, Sletten D, Fealey R, Low P, Singer W. 11-year follow-up of a case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (P03.024). Neurology. 2013;80(7):P03.024.

13. Imrich R, Vernino S, Eldadah BA, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy: treatment by plasma exchanges and rituximab. Clin Auton Res. 2009;19(4):259-262. doi: 10.1007/s10286-009-0012-7. PubMed

14. Iodice V, Kimpinski K, Vernino S, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA. Efficacy of immunotherapy in seropositive and seronegative putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Neurology. 2009;72(23):2002-8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92b52. PubMed

15. Hayashi M, Ishii Y. A Japanese case of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG) and a review of AAG cases in Japan. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146(1-2):26-8. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.12.013. PubMed

16. Baker, A. Simplicity. In: Baker A, Zalta E, eds. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2016 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/simplicity/. Accessed October 26, 2017.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Computer-Based Reminders Have Small to Modest Effect on Care Processes

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Patient Participation in Medication Reconciliation at Discharge Helps Detect Prescribing Discrepancies

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Negative D-Dimer Test Can Safely Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in Patients at Low To Intermediate Clinical Risk

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.