User login

PsA Pathophysiology and Etiology

Obesity Treatment

MCL Treatment

Acute Onset of Vitiligolike Depigmentation After Nivolumab Therapy for Systemic Melanoma

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

Practice Points

- New-onset vitiligo coinciding with malignant melanoma should be considered a good prognostic indicator.

- Daily use of hydroquinone cream 4% in conjunction with diligent photoprotection was shown to even overall skin tone in a patient experiencing leukoderma from nivolumab therapy.

Collision Course of a Basal Cell Carcinoma and Apocrine Hidrocystoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

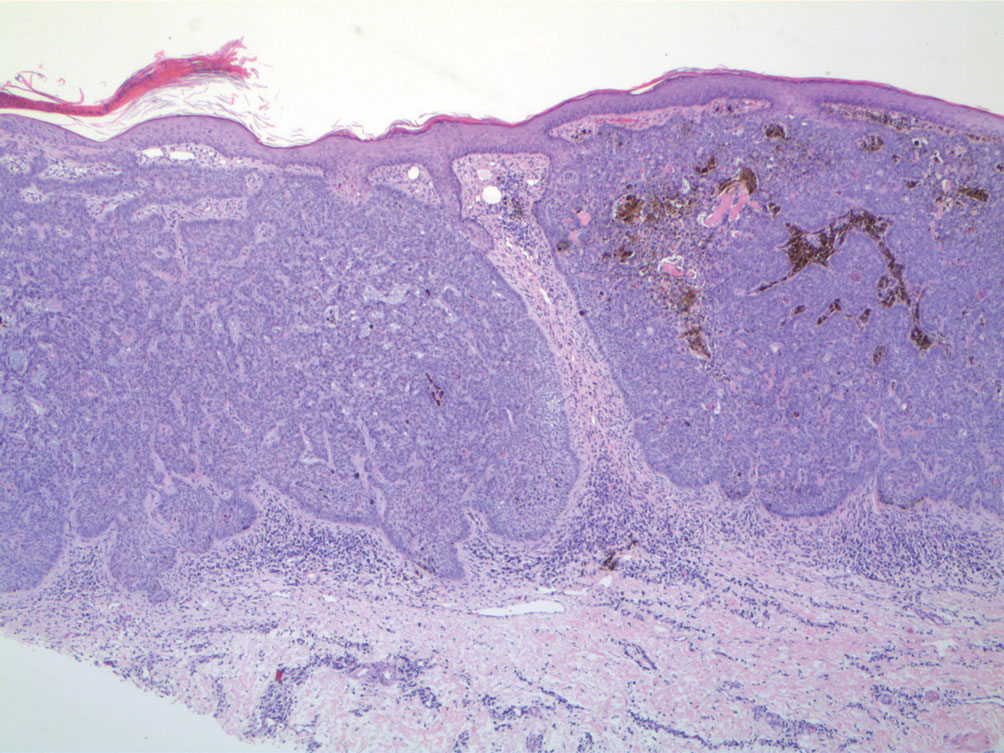

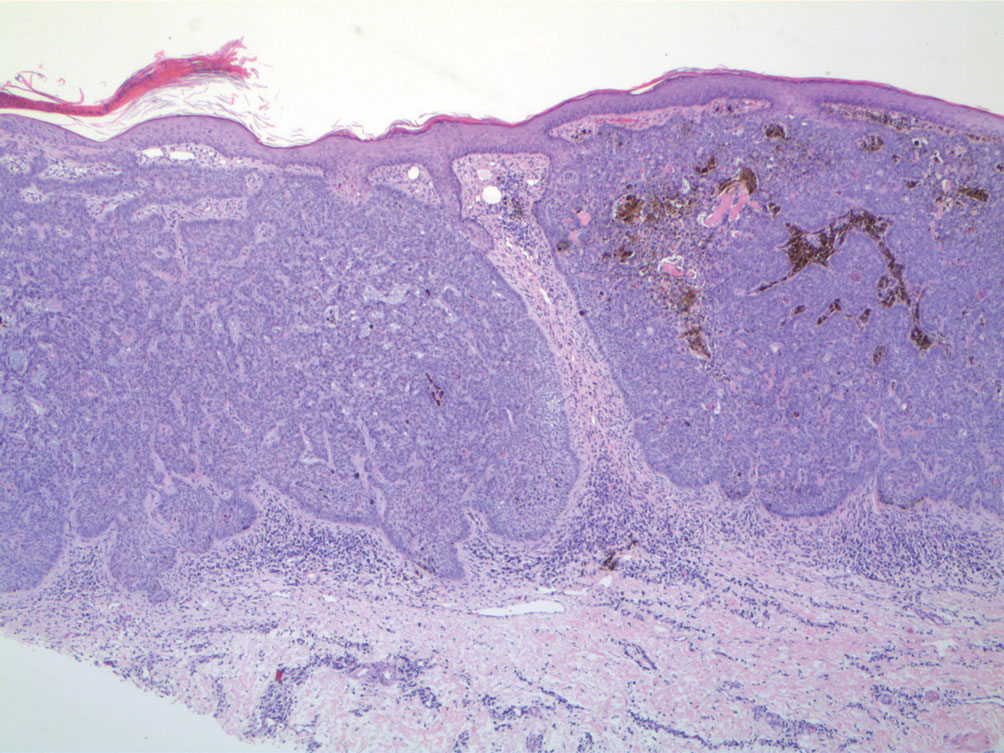

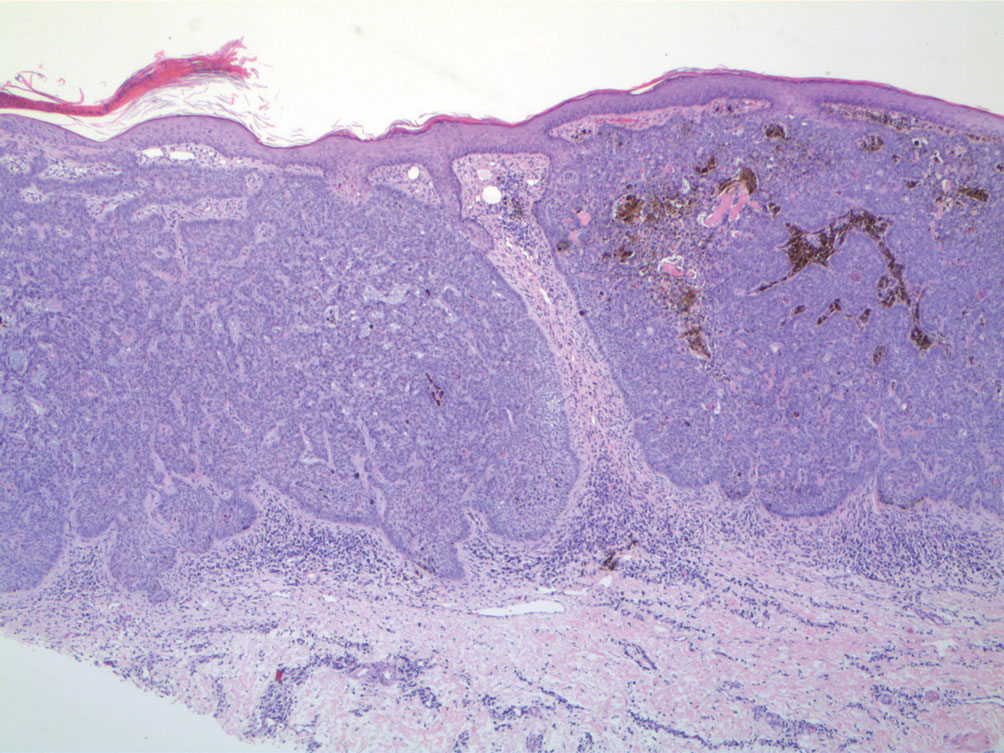

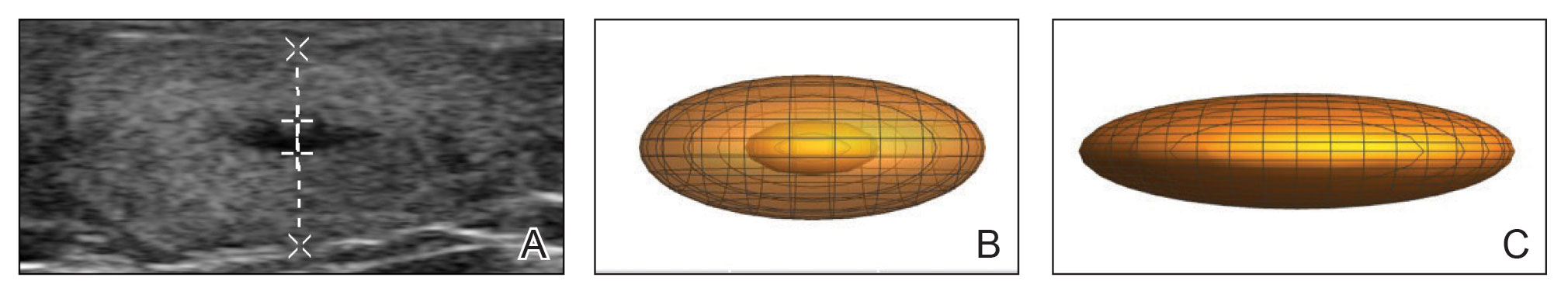

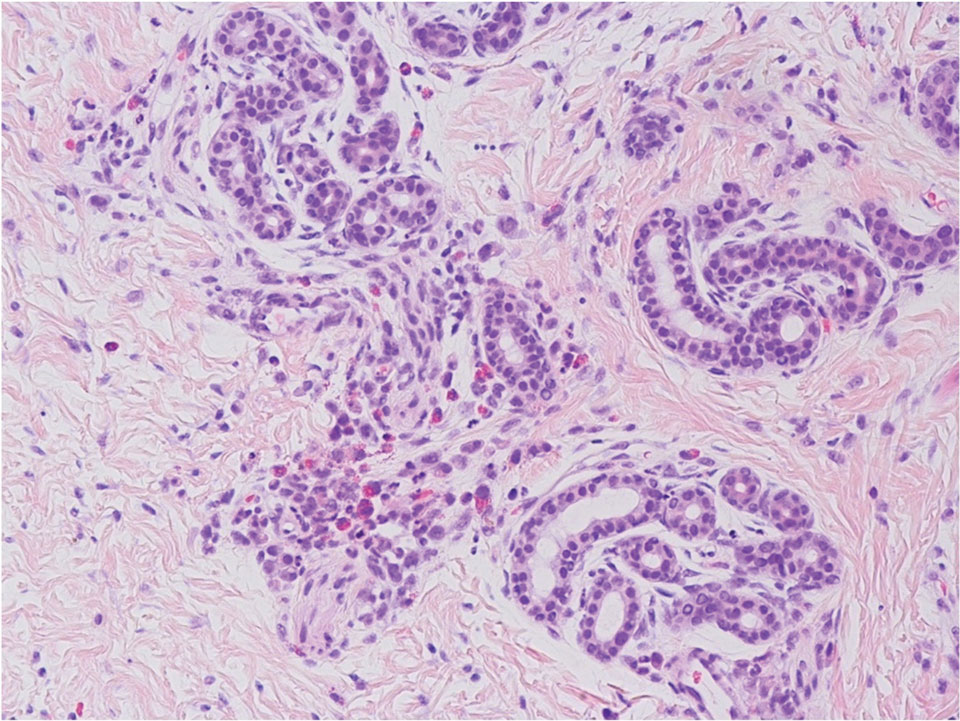

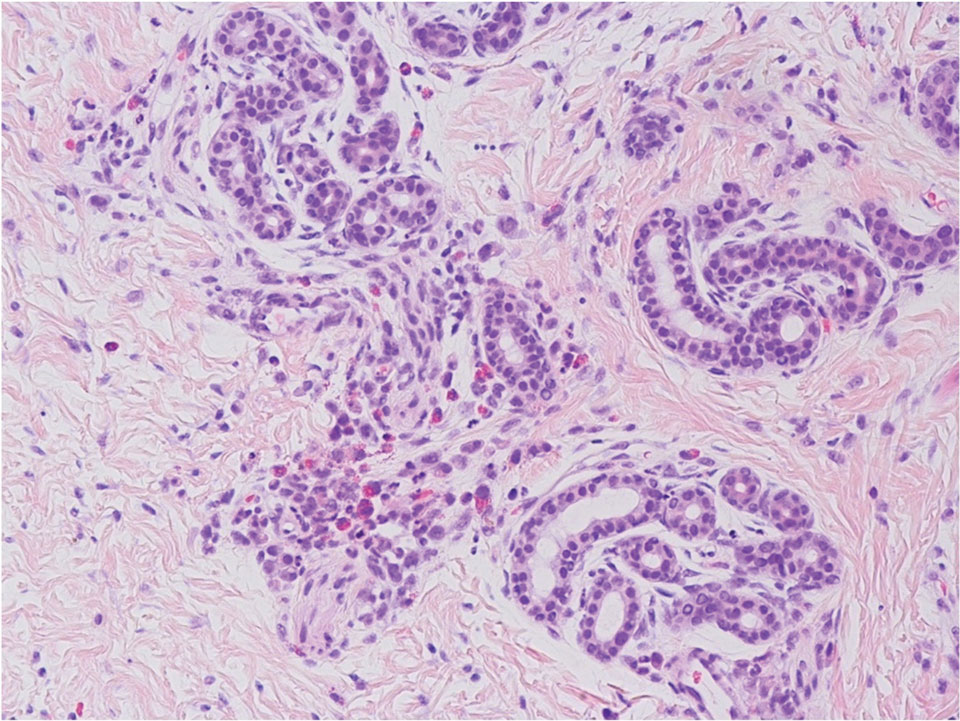

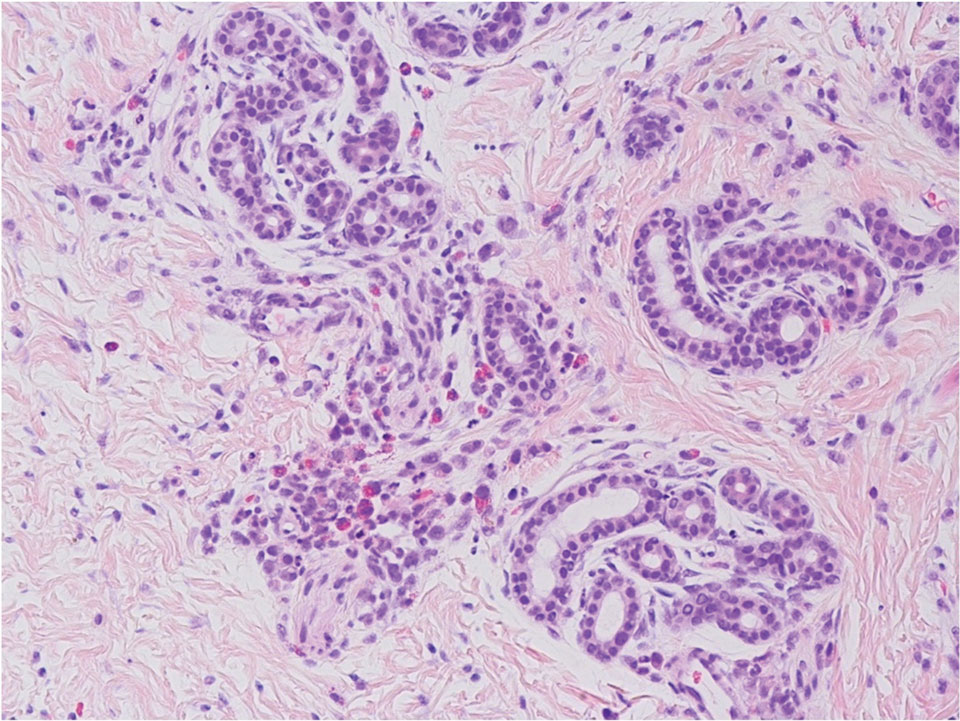

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

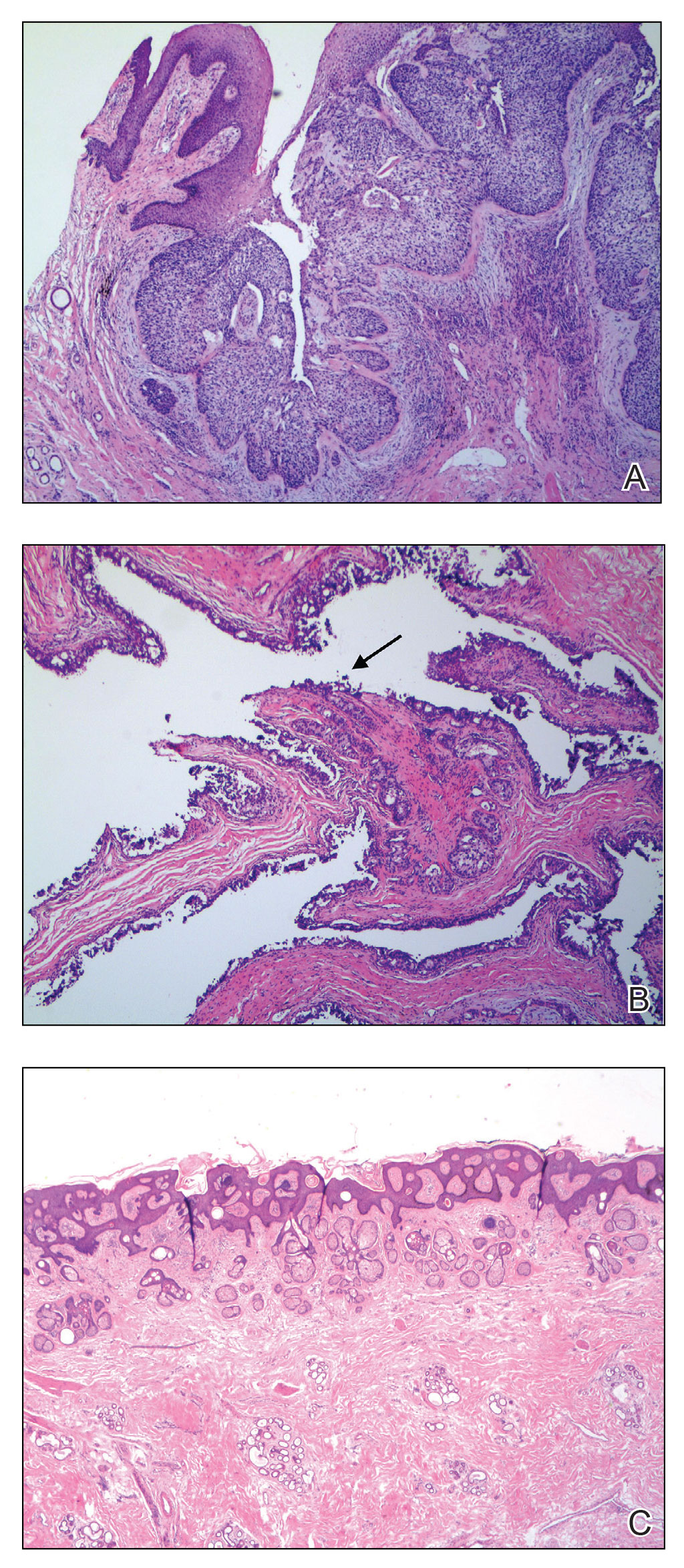

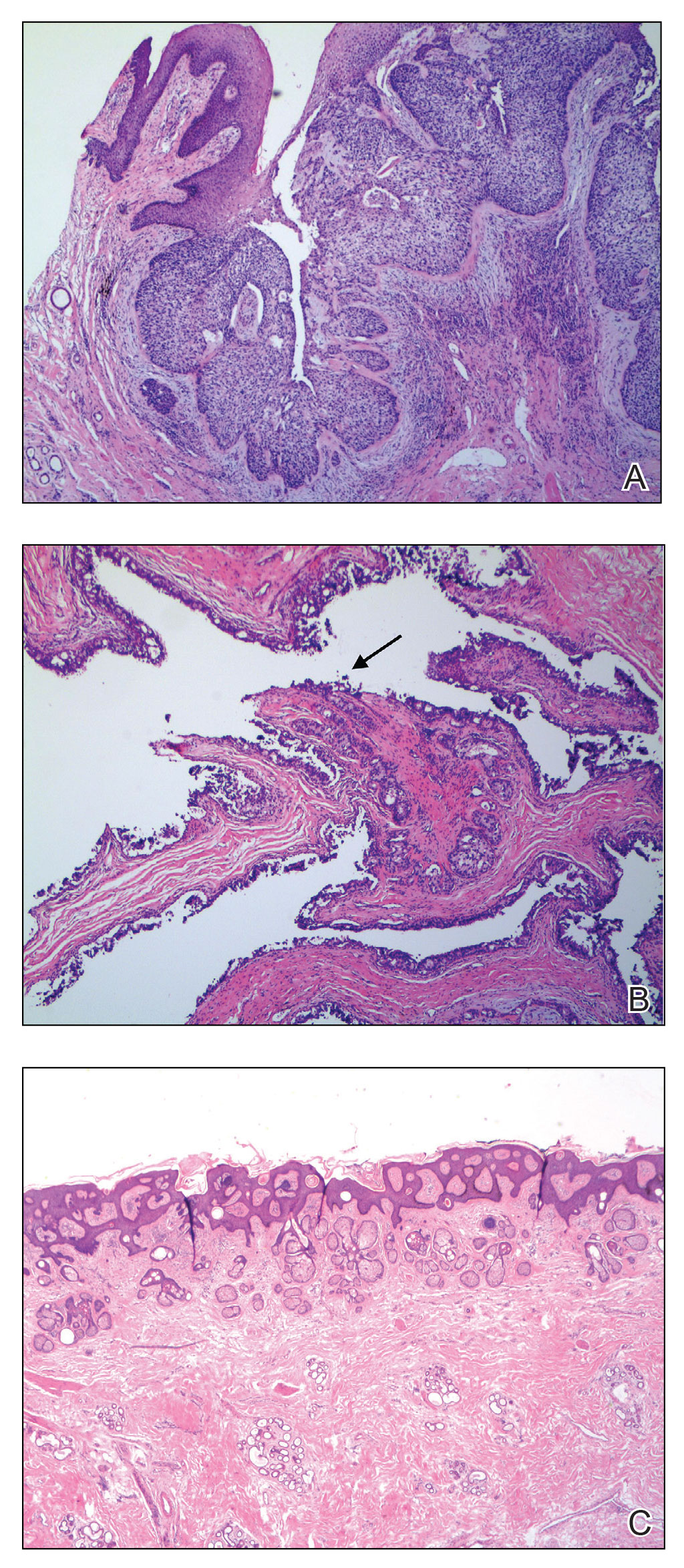

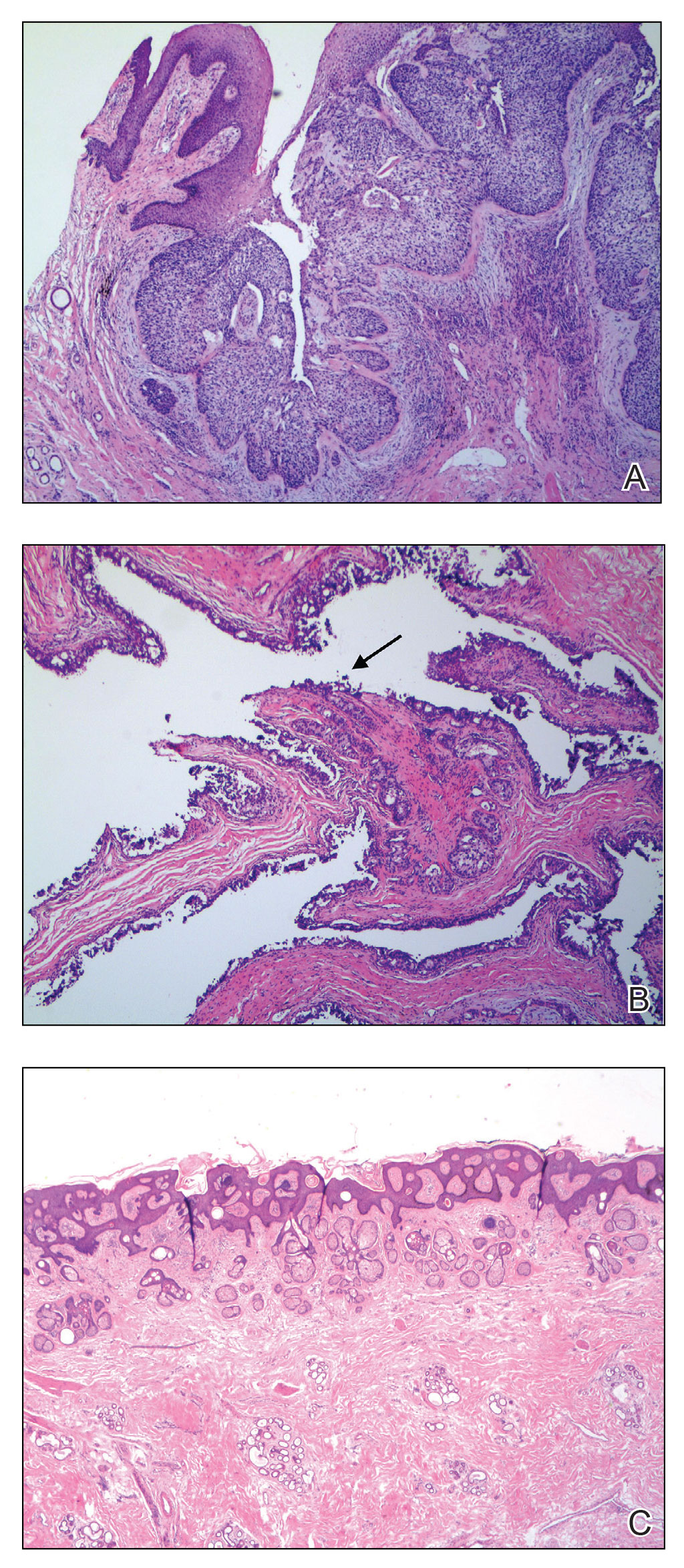

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

PRACTICE POINTS

- When collision tumors are encountered during Mohs micrographic surgery, review of the initial diagnostic material is recommended.

- Permanent processing of Mohs excisions may be helpful in determining the diagnosis of the occult second tumor diagnosis.

Deoxycholic Acid for Dercum Disease: Repurposing a Cosmetic Agent to Treat a Rare Disease

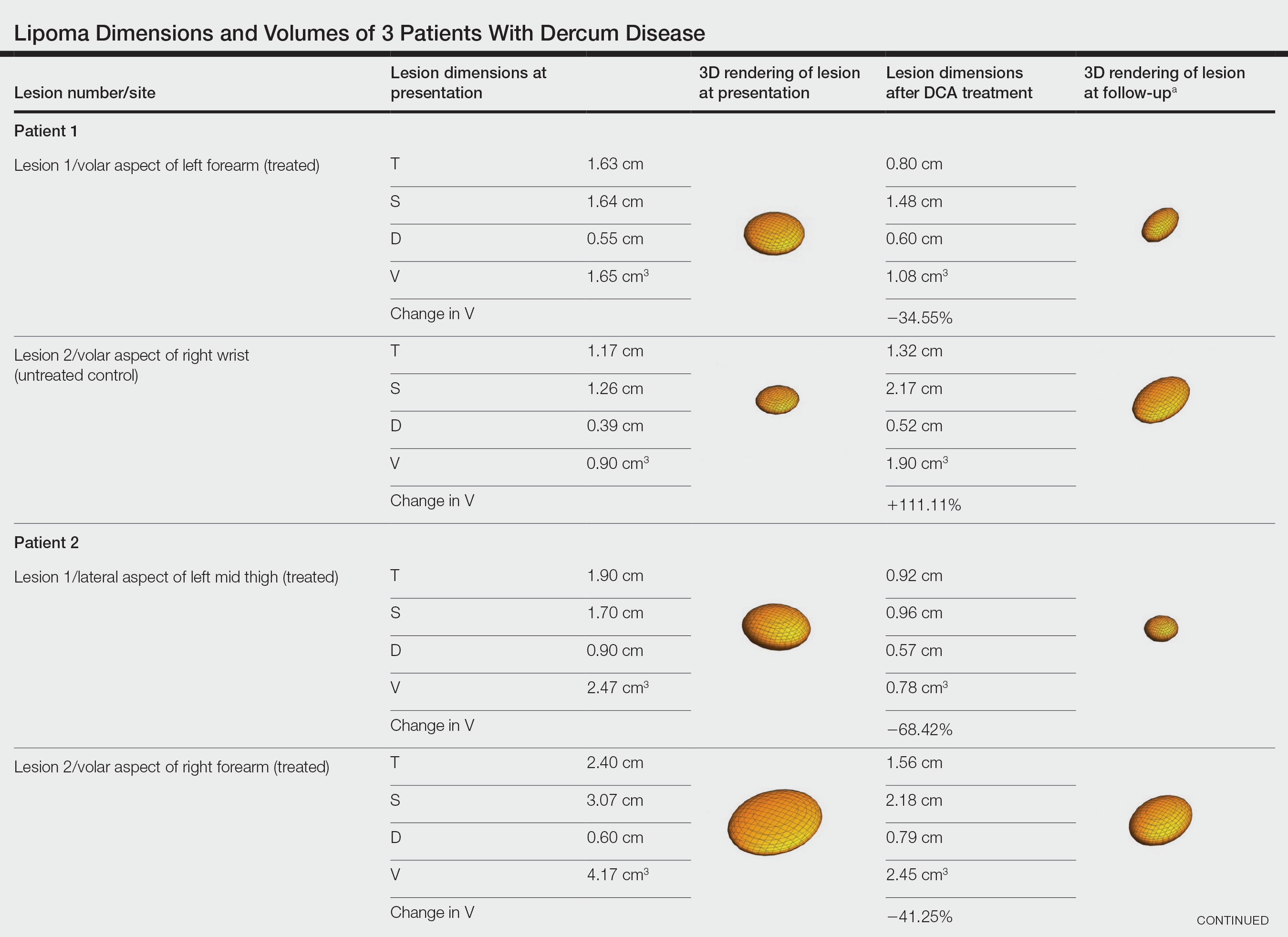

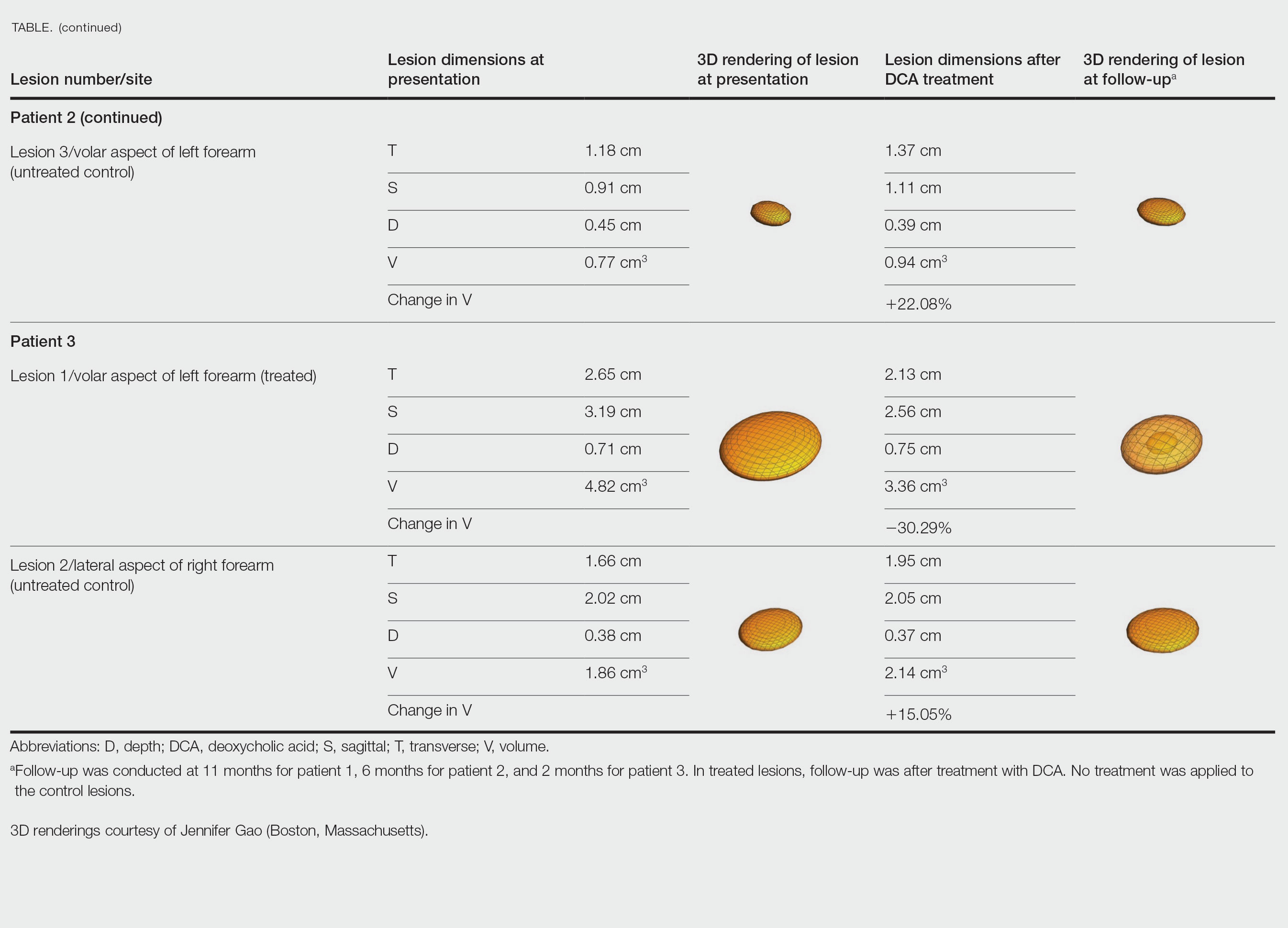

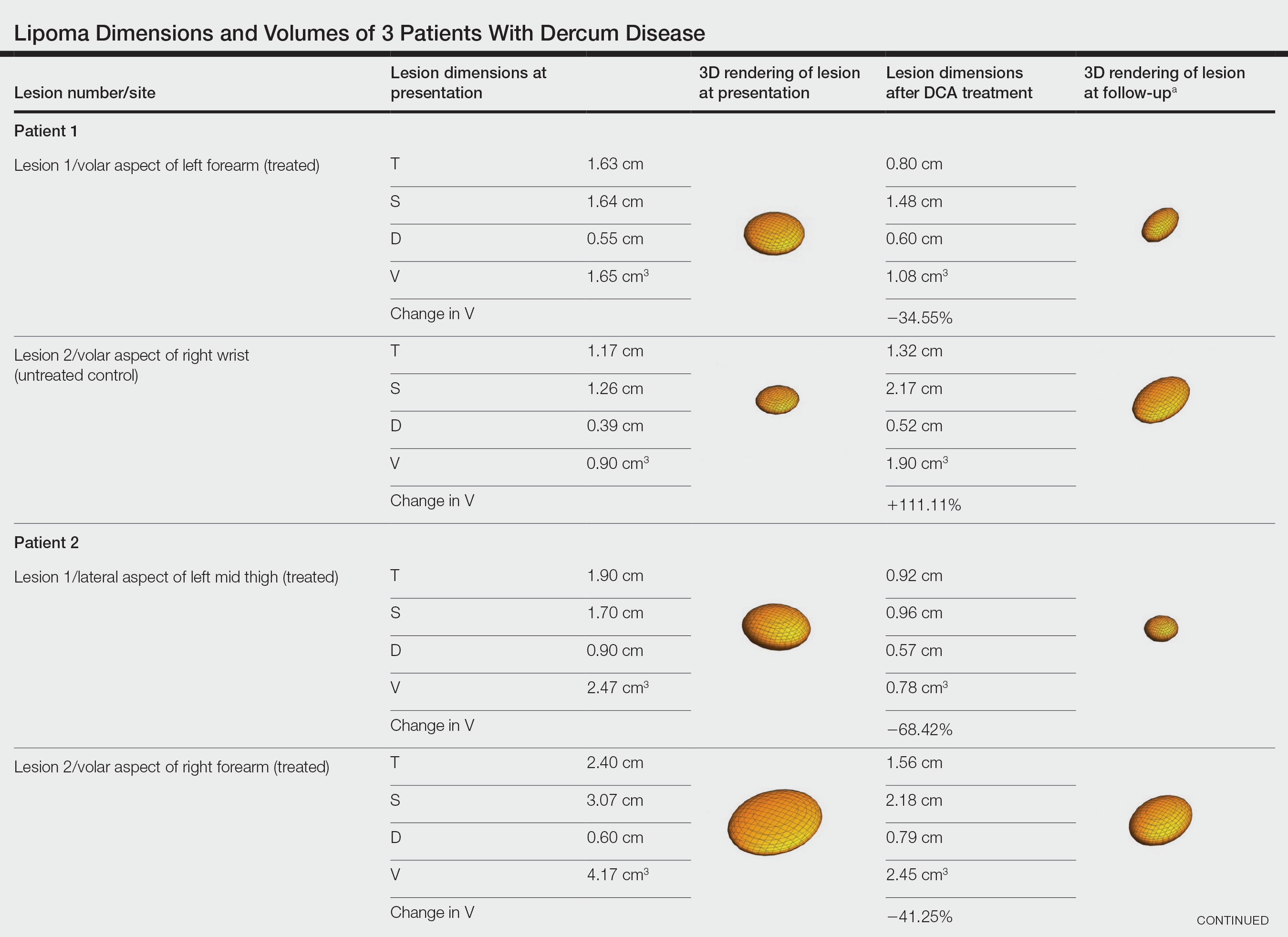

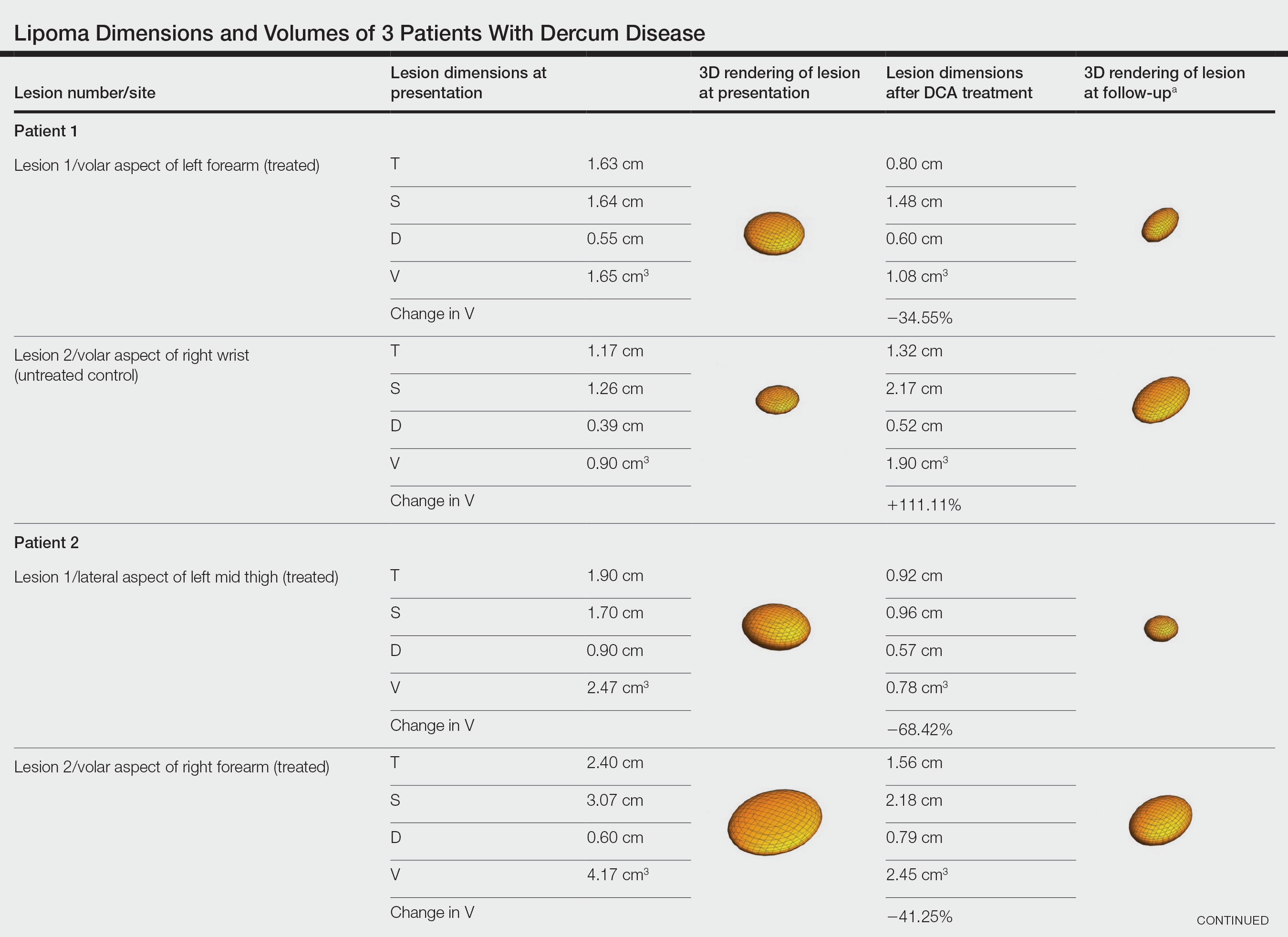

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

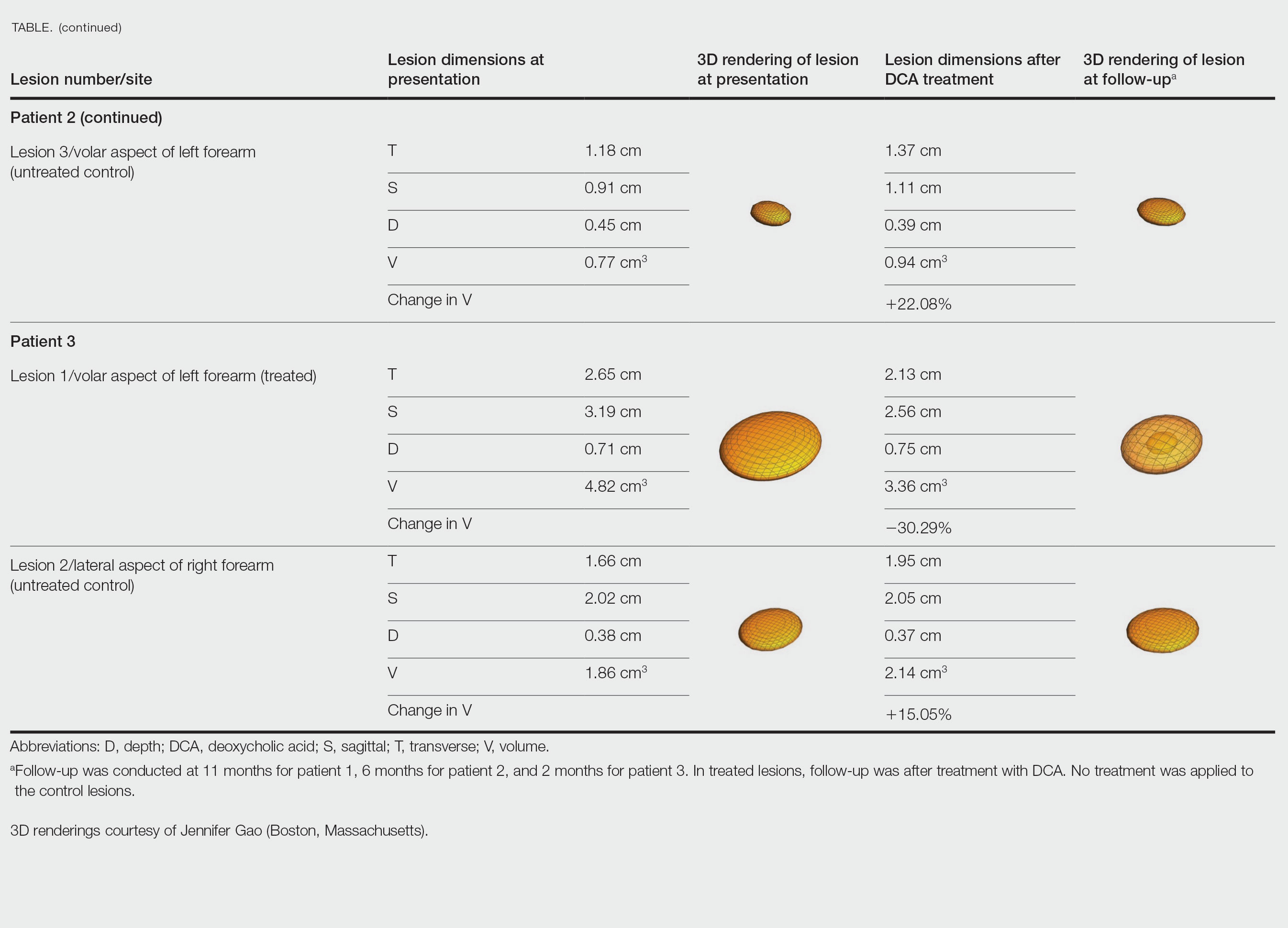

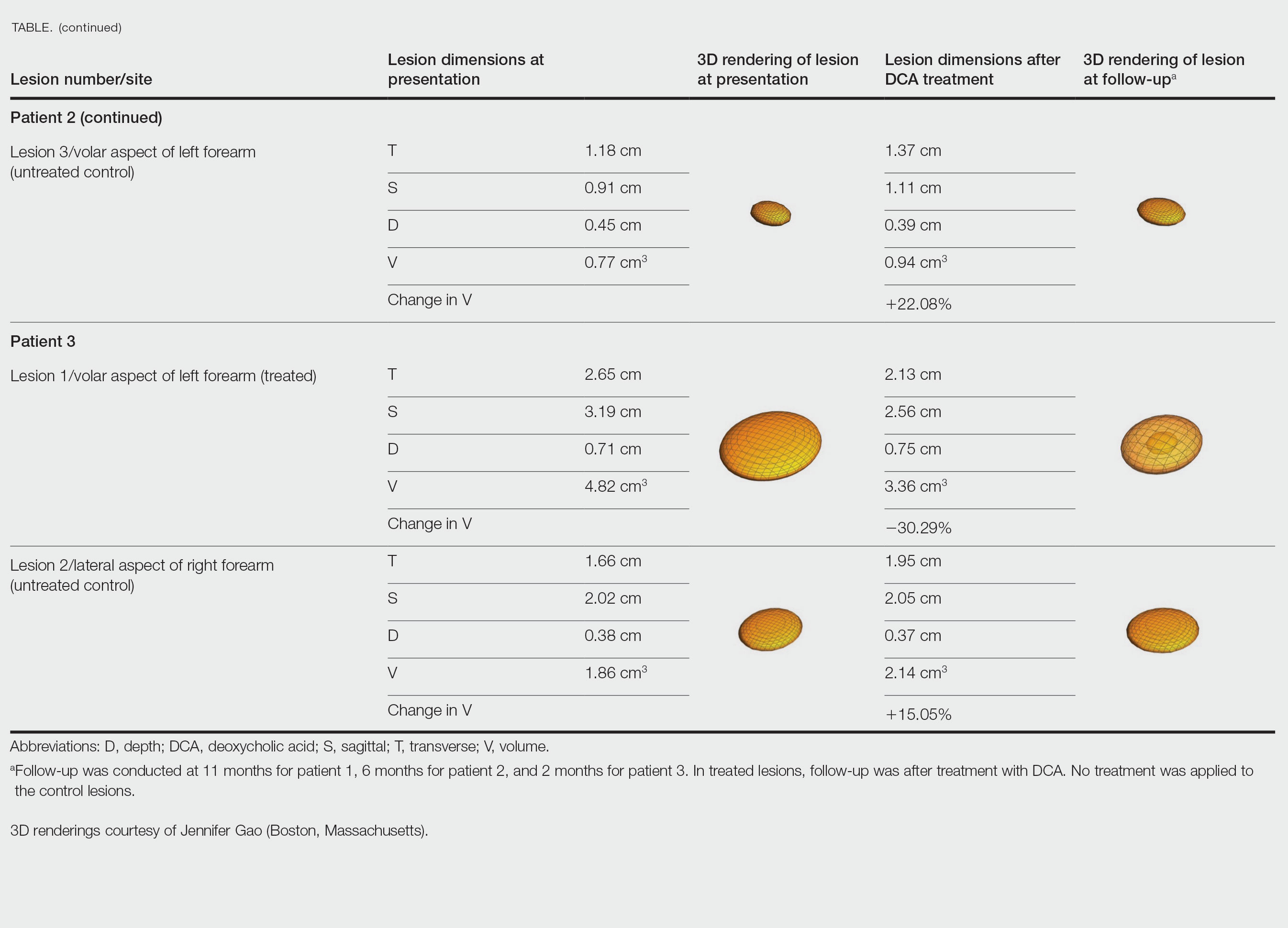

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9