User login

Appetite loss and unusual agitation

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

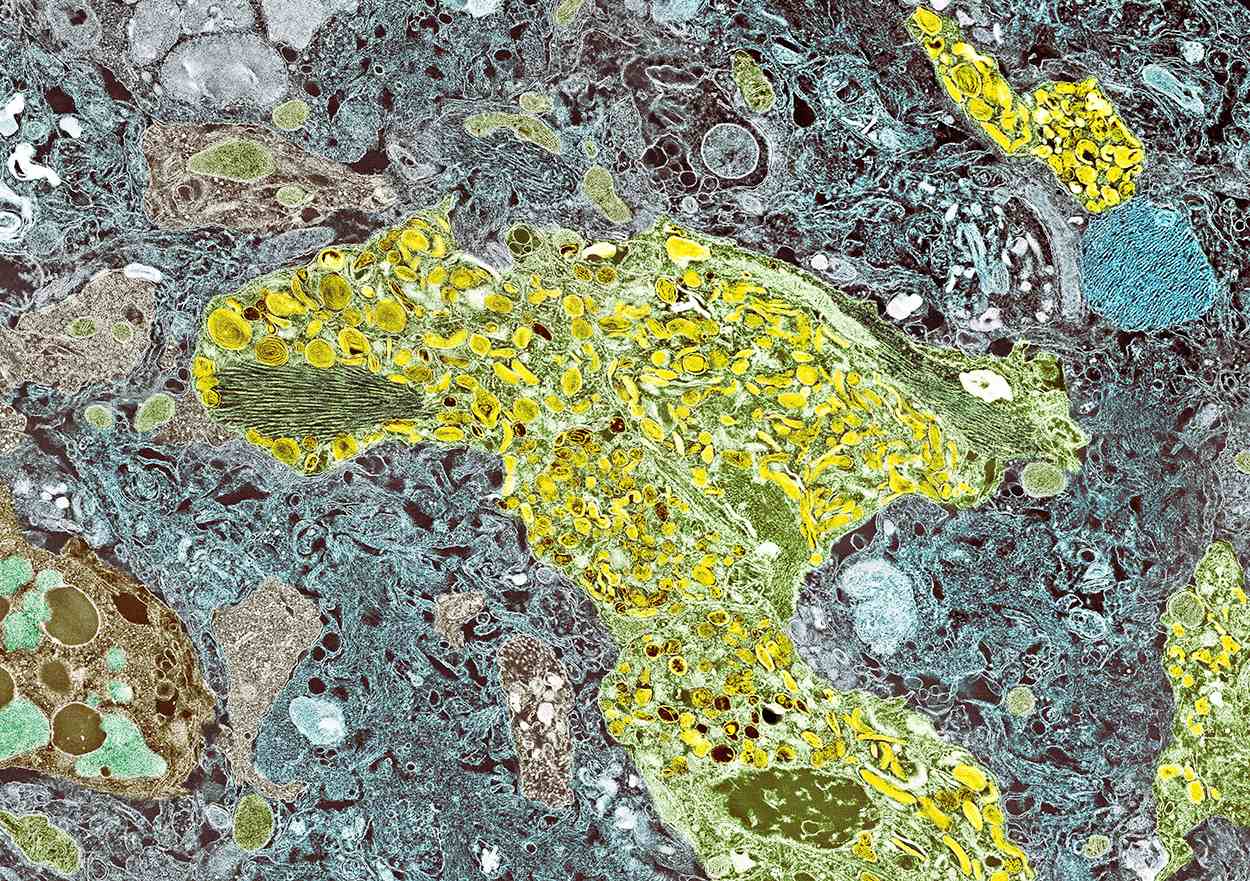

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 85-year-old woman presents to her geriatrician with her daughter, who is her primary caregiver. Seven years ago, the patient was diagnosed with mild Alzheimer's disease (AD). Her symptoms at diagnosis were irritability, forgetfulness, and panic attacks. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional assessments showed levels of decline; neurologic examination revealed mild hyposmia. The patient has been living with her daughter ever since her AD diagnosis.

At today's visit, the daughter reports that her mother has been experiencing loss of appetite and wide mood fluctuations with moments of unusual agitation. In addition, she tells the geriatrician that her mother has had trouble maintaining her balance and seems to have lost her sense of time. The patient has difficulty remembering what month and day it is, and how long it's been since her brother came to visit — which has been every Sunday like clockwork since the patient moved in with her daughter. The daughter also notes that her mother loses track of the story line when she is watching movie and TV shows lately.

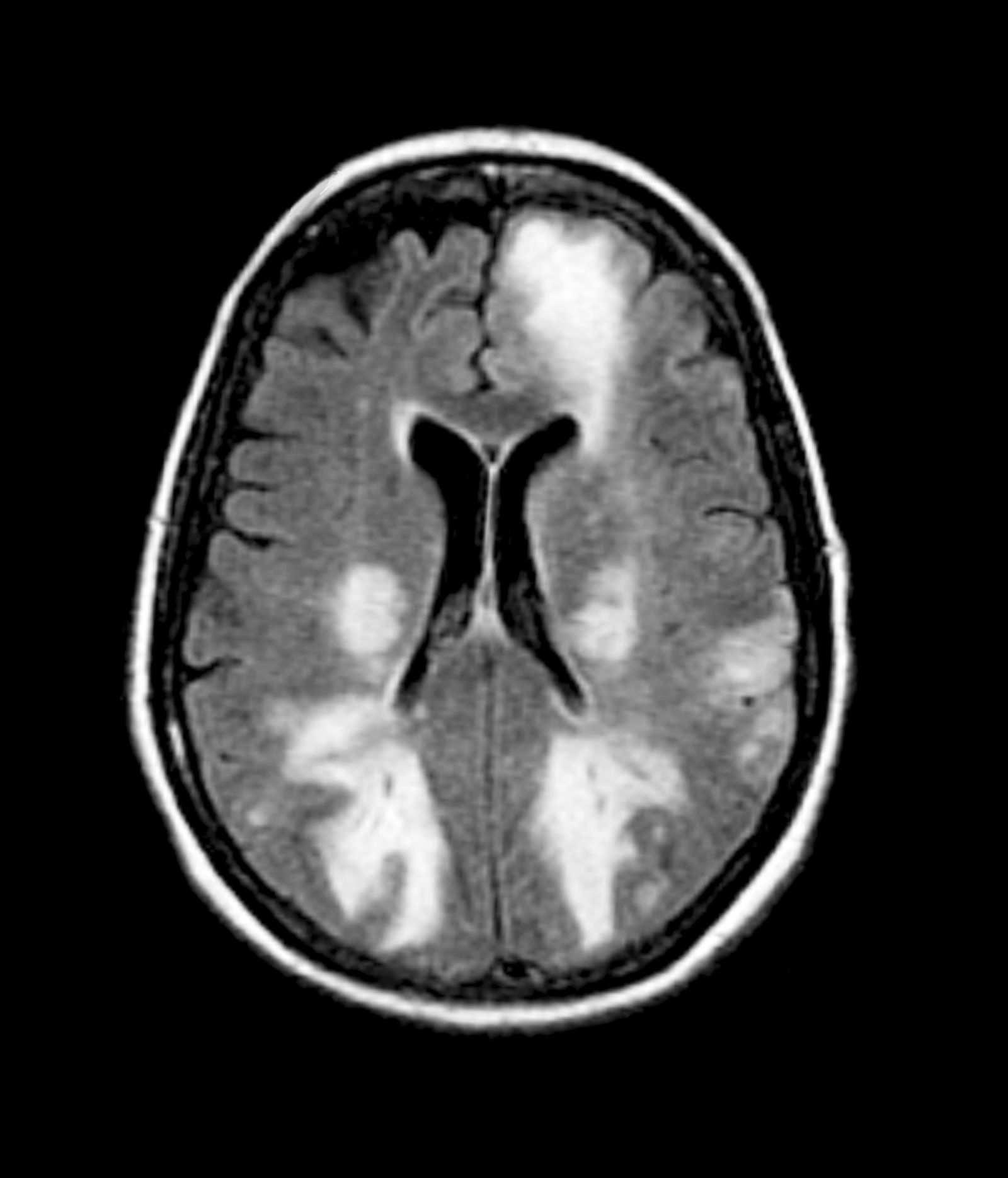

The physician orders a brain MRI and genetic panel. MRI reveals atrophy in the frontal cortex as well as the medial temporal lobe, with hippocampal sclerosis. The genetic panel shows APOE and TMEM106 mutations.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Differential Diagnosis

Forgetfulness and mood fluctuations

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

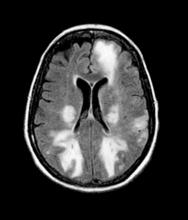

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is a 72-year-old retired schoolteacher accompanied by her daughter. Over the past year, her family has become increasingly concerned about her forgetfulness, mood fluctuations, and challenges in performing daily activities. The patient often forgets her grandchildren's names and struggles to recall significant recent events. She frequently misplaces household items and has missed several appointments. During her consultation, she has difficulty finding the right words, often repeats herself, and seems to lose track of the conversation. Her daughter shared concerning incidents, such as the patient wearing heavy sweaters during hot summer days and falling victim to a phone scam, which was uncharacteristic of her previous discerning nature. Additionally, the patient has become more reclusive, avoiding the social gatherings she once loved. She occasionally exhibits signs of agitation, especially in the evening. She has also stopped cooking as a result of instances of forgetting to turn off the stove and has had challenges managing her finances, leading to unpaid bills. A thorough neurologic exam is performed and is normal. Coronal T1-weighted MRI reveals hippocampal atrophy, particularly on the right side.

Alzheimer's Disease Workup

Anxiety and panic attacks

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

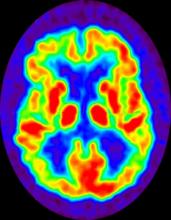

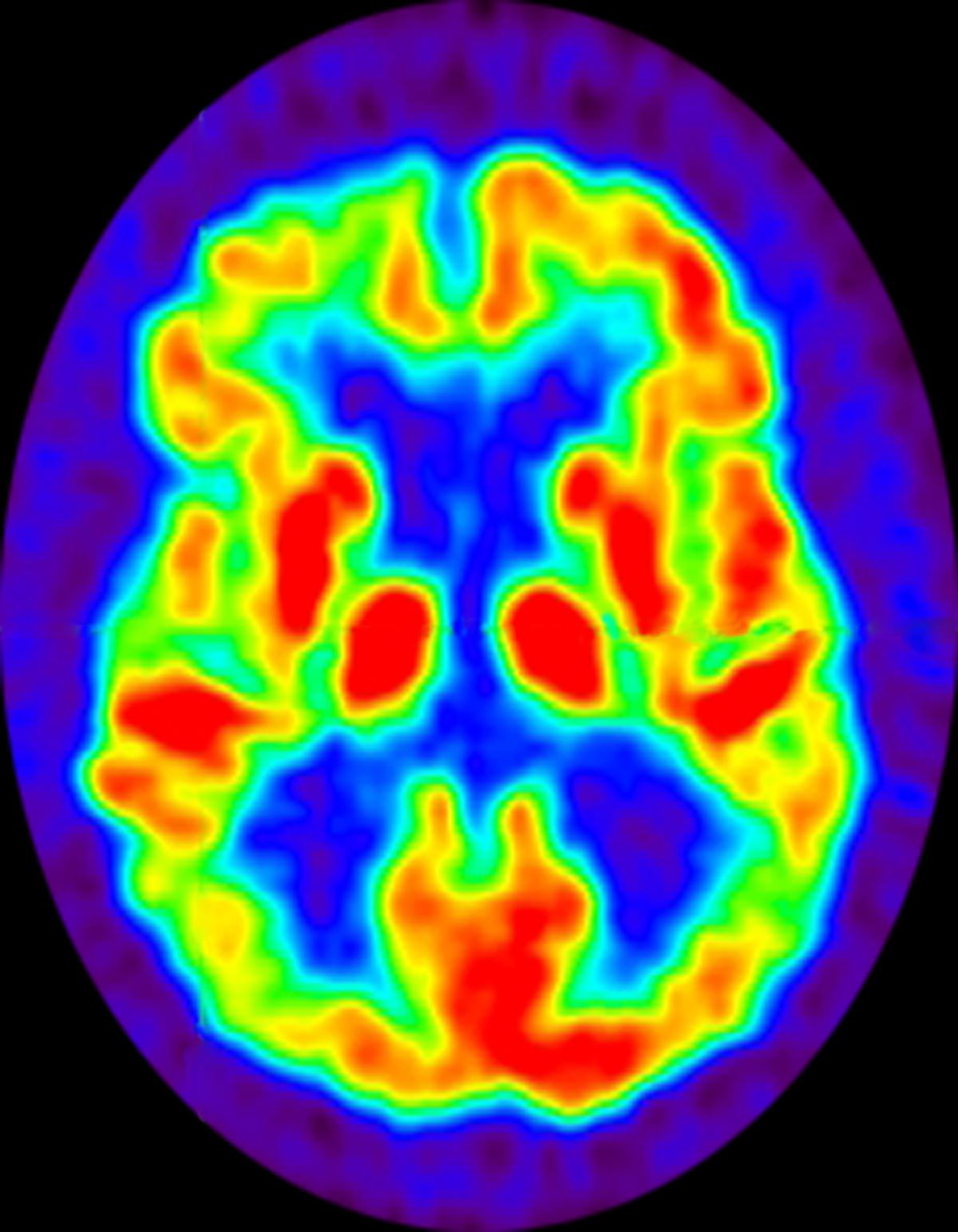

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 73-year-old man who lives independently presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with irritability, anxiety, and panic attacks. Last year, he saw his PCP at the urging of his brother, who noticed that the patient was becoming more forgetful and agitated. At that time, the brother reported concerns that the patient, who normally enjoyed spending time with his extended family, was beginning to regularly forget to show up at family functions. When asked why he hadn't attended, the patient would become irate, saying it was his family who failed to invite him. The patient wouldn't have agreed to seeing the PCP except he was having issues with insomnia that he wanted to address. During last year's visit, the physician conducted a complete physical examination, as well as detailed neurologic and mental status examinations; all came back normal.

At today's visit, in addition to patient-reported mood fluctuations, the brother tells the physician that the patient has become reclusive, skipping nearly all family functions as well as daily walks with friends. His daily hygiene has suffered, and he has stopped eating regularly. The brother also mentions to the doctor that the patient has received some late-payment notices for utilities that he normally meticulously paid on time. The PCP orders another round of cognitive, behavioral, and functional assessments, which reveal a decline in all areas from last year's results, as well as a complete neurologic examination that reveals mild hyposmia.

Forgetfulness and confusion

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 72-year-old woman presents with a 12-month history of short-term memory loss. The patient is accompanied by her husband, who states her symptoms have become increasingly frequent and severe. The patient can no longer drive familiar routes after becoming lost on several occasions. She frequently misplaces items; recently, she placed her husband's car keys in the refrigerator. The patient admits to increasing bouts of forgetfulness and confusion and states that she has been feeling very down. She has not been able to watch her grandchildren over the past few months, which makes her feel sad and old. She also reports trouble sleeping at night due to generalized anxiety.

The patient's past medical history is significant for hypertension and dyslipidemia. There is no history of neurotoxic exposure, head injuries, strokes, or seizures. Her family history is positive for dementia. Her older brother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease (AD) at age 68 years, and her mother died from AD at age 82 years. Current medications include rosuvastatin 20 mg/d and lisinopril 20 mg/d. The patient's current height and weight are 5 ft 5 in and 163 lb, respectively (BMI is 27.1).

No abnormalities are noted on physical examination; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are within normal ranges. The patient scores 18 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. The patient's clinician orders a brain fluorodeoxyglucose-PET, which reveals areas of decreased glucose metabolism involving the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, inferior parietal lobule, and middle temporal gyrus.