User login

Left liver grafts may benefit from hepatic vein/IVC anastomosis

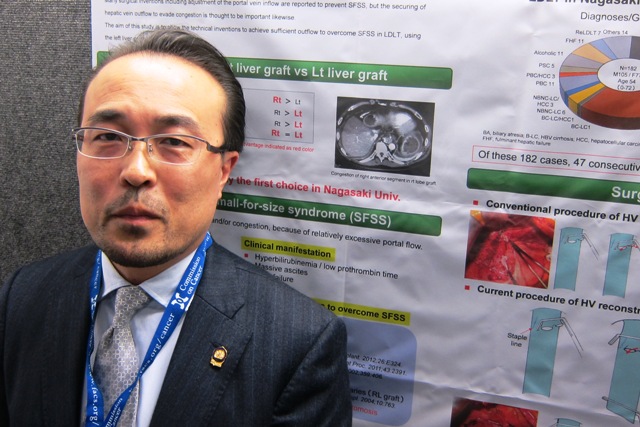

WASHINGTON – A novel anastomosis technique may help avoid small-for-size syndrome in adult living donor liver transplantation, according to Dr. Mitsuhisa Takatsuki.

Reconstructing the hepatic vein by cross-clamping with the inferior vena cava creates improved outflow from the graft. This can avert the potential failure of a left liver graft, which, because of its smaller size, is more prone to the syndrome than is a right liver graft, said Dr. Takatsuki of Nagasaki (Japan) University.

A left liver graft is the first choice for living donor transplant in Japan because this graft is less likely to experience congestion than is a right lobe graft. Donors with a left graft are also less likely to have serious postoperative complications or to die. However, the graft volume of the left liver is less than that of the right, making it susceptible to the problems of a high portal inflow. Dr. Takatsuki’s novel securing of the hepatic vein to the inferior vena cava increases liver outflow and, hopefully, prevents graft congestion, he said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The conventional hepatic vein reconstruction side clamps the middle and left hepatic veins. This common trunk is then joined to the graft hepatic vein. Dr. Takatsuki’s technique takes advantage of the inferior vena cava to increase graft outflow, he noted.

He closes the right hepatic vein with a vascular stapler. He then opens the common trunk of the middle and left hepatic veins and creates a wide cavotomy in the inferior vena cava. "This wide orifice of hepatic vein is anastomosed to the graft hepatic vein. The size of the hepatic vein orifice is easily adjustable to suit the size of the graft hepatic vein," Dr. Takatsuki said.

He reported the results of a study of 47 adult living donor transplants. Of these 47 patients, 21 had the side clamp hepatic vein reconstruction and 26, the new technique of cross-clamping the inferior vena cava.

The patients were a mean of 56 years old and evenly split between men and women. The mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease(MELD) score was 15.5. Surgery lasted a mean of 915 minutes in the side clamp group and 746 minutes in the cross-clamp group – a significant difference. Blood loss was also significantly less in the cross-clamp group (3,800 g vs.5,450 g).

By postoperative day 7, there were no significant between-group differences in total bilirubin or prothrombin time. There was significantly less ascites in the cross-clamp group.

Dr. Takatsuki saw the same results in a subgroup of 17 patients (7 in the side clamp group and 10 in the cross-clamp group) in whom the graft weight/recipient standard liver volume was less than 30%.

Among these patients – who were at the highest risk for graft failure because of the weight/volume differential – those with the cross-clamped anastomosis had significantly higher graft survival (90% vs. 71%) at 1 year.

Dr. Takatsuki said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A novel anastomosis technique may help avoid small-for-size syndrome in adult living donor liver transplantation, according to Dr. Mitsuhisa Takatsuki.

Reconstructing the hepatic vein by cross-clamping with the inferior vena cava creates improved outflow from the graft. This can avert the potential failure of a left liver graft, which, because of its smaller size, is more prone to the syndrome than is a right liver graft, said Dr. Takatsuki of Nagasaki (Japan) University.

A left liver graft is the first choice for living donor transplant in Japan because this graft is less likely to experience congestion than is a right lobe graft. Donors with a left graft are also less likely to have serious postoperative complications or to die. However, the graft volume of the left liver is less than that of the right, making it susceptible to the problems of a high portal inflow. Dr. Takatsuki’s novel securing of the hepatic vein to the inferior vena cava increases liver outflow and, hopefully, prevents graft congestion, he said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The conventional hepatic vein reconstruction side clamps the middle and left hepatic veins. This common trunk is then joined to the graft hepatic vein. Dr. Takatsuki’s technique takes advantage of the inferior vena cava to increase graft outflow, he noted.

He closes the right hepatic vein with a vascular stapler. He then opens the common trunk of the middle and left hepatic veins and creates a wide cavotomy in the inferior vena cava. "This wide orifice of hepatic vein is anastomosed to the graft hepatic vein. The size of the hepatic vein orifice is easily adjustable to suit the size of the graft hepatic vein," Dr. Takatsuki said.

He reported the results of a study of 47 adult living donor transplants. Of these 47 patients, 21 had the side clamp hepatic vein reconstruction and 26, the new technique of cross-clamping the inferior vena cava.

The patients were a mean of 56 years old and evenly split between men and women. The mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease(MELD) score was 15.5. Surgery lasted a mean of 915 minutes in the side clamp group and 746 minutes in the cross-clamp group – a significant difference. Blood loss was also significantly less in the cross-clamp group (3,800 g vs.5,450 g).

By postoperative day 7, there were no significant between-group differences in total bilirubin or prothrombin time. There was significantly less ascites in the cross-clamp group.

Dr. Takatsuki saw the same results in a subgroup of 17 patients (7 in the side clamp group and 10 in the cross-clamp group) in whom the graft weight/recipient standard liver volume was less than 30%.

Among these patients – who were at the highest risk for graft failure because of the weight/volume differential – those with the cross-clamped anastomosis had significantly higher graft survival (90% vs. 71%) at 1 year.

Dr. Takatsuki said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A novel anastomosis technique may help avoid small-for-size syndrome in adult living donor liver transplantation, according to Dr. Mitsuhisa Takatsuki.

Reconstructing the hepatic vein by cross-clamping with the inferior vena cava creates improved outflow from the graft. This can avert the potential failure of a left liver graft, which, because of its smaller size, is more prone to the syndrome than is a right liver graft, said Dr. Takatsuki of Nagasaki (Japan) University.

A left liver graft is the first choice for living donor transplant in Japan because this graft is less likely to experience congestion than is a right lobe graft. Donors with a left graft are also less likely to have serious postoperative complications or to die. However, the graft volume of the left liver is less than that of the right, making it susceptible to the problems of a high portal inflow. Dr. Takatsuki’s novel securing of the hepatic vein to the inferior vena cava increases liver outflow and, hopefully, prevents graft congestion, he said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The conventional hepatic vein reconstruction side clamps the middle and left hepatic veins. This common trunk is then joined to the graft hepatic vein. Dr. Takatsuki’s technique takes advantage of the inferior vena cava to increase graft outflow, he noted.

He closes the right hepatic vein with a vascular stapler. He then opens the common trunk of the middle and left hepatic veins and creates a wide cavotomy in the inferior vena cava. "This wide orifice of hepatic vein is anastomosed to the graft hepatic vein. The size of the hepatic vein orifice is easily adjustable to suit the size of the graft hepatic vein," Dr. Takatsuki said.

He reported the results of a study of 47 adult living donor transplants. Of these 47 patients, 21 had the side clamp hepatic vein reconstruction and 26, the new technique of cross-clamping the inferior vena cava.

The patients were a mean of 56 years old and evenly split between men and women. The mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease(MELD) score was 15.5. Surgery lasted a mean of 915 minutes in the side clamp group and 746 minutes in the cross-clamp group – a significant difference. Blood loss was also significantly less in the cross-clamp group (3,800 g vs.5,450 g).

By postoperative day 7, there were no significant between-group differences in total bilirubin or prothrombin time. There was significantly less ascites in the cross-clamp group.

Dr. Takatsuki saw the same results in a subgroup of 17 patients (7 in the side clamp group and 10 in the cross-clamp group) in whom the graft weight/recipient standard liver volume was less than 30%.

Among these patients – who were at the highest risk for graft failure because of the weight/volume differential – those with the cross-clamped anastomosis had significantly higher graft survival (90% vs. 71%) at 1 year.

Dr. Takatsuki said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS Clincal Congress

Major finding: One-year liver graft survival was significantly better in patients with a hepatic vein/inferior vena cava anastomosis than in those who had the traditional hepatic vein side clamp (90% vs. 71%).

Data source: A randomized study involving 47 patients who received a living donor left liver transplant.

Disclosures: Dr. Takatsuki said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

In HCC, histology and parenchyma more important than tumor size

ORLANDO – In hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor size did not independently influence recurrence or survival, whereas tumor histopathology and background parenchyma did, according to a retrospective, single-center study of 300 patients.

"These findings further support that prognosis and treatment guidelines cannot be effectively categorized based on tumor size," said Dr. Michael D. Kluger of the department of surgery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital–Cornell University, New York.

Although the procedure is hampered by high recurrence rates, resection is safe, readily available, and offers good overall survival, he said.

Also, "This strategy can allow for the more effective utilization of a limited (and dwindling) supply of transplantable livers; freeing other patients from the potential short- and long-term complications of undergoing unnecessary transplantation," Dr. Kluger said.

Meanwhile, "many treatments with curative intent remain available after recurrence, including re-resection, salvage transplantation, and ablation," he said.

He presented his abstract, which is not published, during the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Kluger and his colleagues studied 313 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver resection between 1989 and 2010.

Patients were stratified based on tumor size of less than 50 mm (36%), 50-100 mm (36%), and more than 100 mm (28%).

Patients with larger tumors were more likely to have normal liver parenchyma: 43% of patients with tumors larger than 100 mm, compared with 1% of patients with tumors smaller than 50 mm (P less than .001).

The influence of tumor size on overall survival was significant in univariate analyses (less than 50 mm vs. 50-100 mm, P = .0321; less then 50 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = 0.009; 50-100 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = .57), said Dr. Kluger, but when the salvage transplantation cases were excluded, tumor size was no longer significant (P = .18, .07, and .65, respectively.)

Researchers found seven independent predictors that led to decreased overall survival: intraoperative transfusion (hazard ratio, 2.60), cirrhosis (HR, 2.42), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 2.04), satellite lesions (HR, 1.68), microvascular invasion (HR, 1.48), alpha-fetoprotein more than 200 ng/mL (HR, 1.53), and salvage transplantation (HR, 0.23).

Median overall survival was 60 months. One-year overall survival was 76%, and 5-year overall survival was 50%. Meanwhile, 5-year survival of patients who underwent salvage transplantation from the time of occurrence was 90%, compared with 18% for those not undergoing the procedure (P less than .0001).

The median time to recurrence was 20 months, with 1-year recurrence-free survival at 61%, and 5-year recurrence-free survival at 28%.

Four variables independently affected recurrence-free survival, the authors noted: intra-operative transfusion (HR, 2.15), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 1.87), cirrhosis (HR, 1.69), and microvascular invasion (HR, 1.71).

Patients with nontransplantable recurrences after resection of tumors smaller than 5 cm had similar overall survival, compared with patients whose tumors were originally 5 cm or larger.

The study also showed that the rate of complications decreased during the second decade of the study period. While the mortality rate between 1989 and 1999 was 14%, it dropped to 5% through 2010 (P less than .008).

"These improvements coincide with major advances in liver surgery, patient selection, anesthetic practices, liver imaging, and postoperative care," said Dr. Kluger in an interview. "We also believe that routine integration of laparoscopy for appropriate cases since 1998 was also critical to improvements in outcomes. Whereas 6% of the cases performed prior to 2000 utilized a laparoscopic technique, 30% performed after 2000 did."

Dr. Kluger said that "tumor size is a widely accepted but inadequate proxy for interactions within the tumor milieu. ... The onus is to determine which patients would most benefit from upfront listing for transplantation despite candidacy for resection, or resection with the future possibility of salvage transplantation for recurrence," he said.

Dr. Kluger had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

ORLANDO – In hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor size did not independently influence recurrence or survival, whereas tumor histopathology and background parenchyma did, according to a retrospective, single-center study of 300 patients.

"These findings further support that prognosis and treatment guidelines cannot be effectively categorized based on tumor size," said Dr. Michael D. Kluger of the department of surgery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital–Cornell University, New York.

Although the procedure is hampered by high recurrence rates, resection is safe, readily available, and offers good overall survival, he said.

Also, "This strategy can allow for the more effective utilization of a limited (and dwindling) supply of transplantable livers; freeing other patients from the potential short- and long-term complications of undergoing unnecessary transplantation," Dr. Kluger said.

Meanwhile, "many treatments with curative intent remain available after recurrence, including re-resection, salvage transplantation, and ablation," he said.

He presented his abstract, which is not published, during the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Kluger and his colleagues studied 313 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver resection between 1989 and 2010.

Patients were stratified based on tumor size of less than 50 mm (36%), 50-100 mm (36%), and more than 100 mm (28%).

Patients with larger tumors were more likely to have normal liver parenchyma: 43% of patients with tumors larger than 100 mm, compared with 1% of patients with tumors smaller than 50 mm (P less than .001).

The influence of tumor size on overall survival was significant in univariate analyses (less than 50 mm vs. 50-100 mm, P = .0321; less then 50 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = 0.009; 50-100 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = .57), said Dr. Kluger, but when the salvage transplantation cases were excluded, tumor size was no longer significant (P = .18, .07, and .65, respectively.)

Researchers found seven independent predictors that led to decreased overall survival: intraoperative transfusion (hazard ratio, 2.60), cirrhosis (HR, 2.42), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 2.04), satellite lesions (HR, 1.68), microvascular invasion (HR, 1.48), alpha-fetoprotein more than 200 ng/mL (HR, 1.53), and salvage transplantation (HR, 0.23).

Median overall survival was 60 months. One-year overall survival was 76%, and 5-year overall survival was 50%. Meanwhile, 5-year survival of patients who underwent salvage transplantation from the time of occurrence was 90%, compared with 18% for those not undergoing the procedure (P less than .0001).

The median time to recurrence was 20 months, with 1-year recurrence-free survival at 61%, and 5-year recurrence-free survival at 28%.

Four variables independently affected recurrence-free survival, the authors noted: intra-operative transfusion (HR, 2.15), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 1.87), cirrhosis (HR, 1.69), and microvascular invasion (HR, 1.71).

Patients with nontransplantable recurrences after resection of tumors smaller than 5 cm had similar overall survival, compared with patients whose tumors were originally 5 cm or larger.

The study also showed that the rate of complications decreased during the second decade of the study period. While the mortality rate between 1989 and 1999 was 14%, it dropped to 5% through 2010 (P less than .008).

"These improvements coincide with major advances in liver surgery, patient selection, anesthetic practices, liver imaging, and postoperative care," said Dr. Kluger in an interview. "We also believe that routine integration of laparoscopy for appropriate cases since 1998 was also critical to improvements in outcomes. Whereas 6% of the cases performed prior to 2000 utilized a laparoscopic technique, 30% performed after 2000 did."

Dr. Kluger said that "tumor size is a widely accepted but inadequate proxy for interactions within the tumor milieu. ... The onus is to determine which patients would most benefit from upfront listing for transplantation despite candidacy for resection, or resection with the future possibility of salvage transplantation for recurrence," he said.

Dr. Kluger had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

ORLANDO – In hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor size did not independently influence recurrence or survival, whereas tumor histopathology and background parenchyma did, according to a retrospective, single-center study of 300 patients.

"These findings further support that prognosis and treatment guidelines cannot be effectively categorized based on tumor size," said Dr. Michael D. Kluger of the department of surgery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital–Cornell University, New York.

Although the procedure is hampered by high recurrence rates, resection is safe, readily available, and offers good overall survival, he said.

Also, "This strategy can allow for the more effective utilization of a limited (and dwindling) supply of transplantable livers; freeing other patients from the potential short- and long-term complications of undergoing unnecessary transplantation," Dr. Kluger said.

Meanwhile, "many treatments with curative intent remain available after recurrence, including re-resection, salvage transplantation, and ablation," he said.

He presented his abstract, which is not published, during the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Kluger and his colleagues studied 313 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver resection between 1989 and 2010.

Patients were stratified based on tumor size of less than 50 mm (36%), 50-100 mm (36%), and more than 100 mm (28%).

Patients with larger tumors were more likely to have normal liver parenchyma: 43% of patients with tumors larger than 100 mm, compared with 1% of patients with tumors smaller than 50 mm (P less than .001).

The influence of tumor size on overall survival was significant in univariate analyses (less than 50 mm vs. 50-100 mm, P = .0321; less then 50 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = 0.009; 50-100 mm vs. more than 100 mm, P = .57), said Dr. Kluger, but when the salvage transplantation cases were excluded, tumor size was no longer significant (P = .18, .07, and .65, respectively.)

Researchers found seven independent predictors that led to decreased overall survival: intraoperative transfusion (hazard ratio, 2.60), cirrhosis (HR, 2.42), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 2.04), satellite lesions (HR, 1.68), microvascular invasion (HR, 1.48), alpha-fetoprotein more than 200 ng/mL (HR, 1.53), and salvage transplantation (HR, 0.23).

Median overall survival was 60 months. One-year overall survival was 76%, and 5-year overall survival was 50%. Meanwhile, 5-year survival of patients who underwent salvage transplantation from the time of occurrence was 90%, compared with 18% for those not undergoing the procedure (P less than .0001).

The median time to recurrence was 20 months, with 1-year recurrence-free survival at 61%, and 5-year recurrence-free survival at 28%.

Four variables independently affected recurrence-free survival, the authors noted: intra-operative transfusion (HR, 2.15), poorly differentiated tumor (HR, 1.87), cirrhosis (HR, 1.69), and microvascular invasion (HR, 1.71).

Patients with nontransplantable recurrences after resection of tumors smaller than 5 cm had similar overall survival, compared with patients whose tumors were originally 5 cm or larger.

The study also showed that the rate of complications decreased during the second decade of the study period. While the mortality rate between 1989 and 1999 was 14%, it dropped to 5% through 2010 (P less than .008).

"These improvements coincide with major advances in liver surgery, patient selection, anesthetic practices, liver imaging, and postoperative care," said Dr. Kluger in an interview. "We also believe that routine integration of laparoscopy for appropriate cases since 1998 was also critical to improvements in outcomes. Whereas 6% of the cases performed prior to 2000 utilized a laparoscopic technique, 30% performed after 2000 did."

Dr. Kluger said that "tumor size is a widely accepted but inadequate proxy for interactions within the tumor milieu. ... The onus is to determine which patients would most benefit from upfront listing for transplantation despite candidacy for resection, or resection with the future possibility of salvage transplantation for recurrence," he said.

Dr. Kluger had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AT DDW 2013

Major finding: The influence of tumor size on overall survival was significant in univariate analyses but when the salvage transplantation cases were excluded, tumor size was no longer significant.

Data source: Study of 313 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent liver resection between 1989 and 2010 at a single center.

Disclosures: Dr. Kluger had no disclosures.

Home discharge with total artificial heart is feasible, safe

LOS ANGELES – Some patients with a total artificial heart can safely go home with the use of a small portable driver while awaiting heart transplantation, according to data from the first U.S. patient cohort in whom this was attempted.

Investigators assessed outcomes in 13 total artificial heart recipients who were stable enough clinically to be transitioned from the usual driver to SynCardia Systems’ investigational portable driver, the Freedom Driver System. The driver weighs 14 pounds and allows several hours of untethered activity.

Eight of the patients were able to go home for an average of 5.5 months, lead investigator Dr. Vigneshwar Kasirajan reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

They had a low rate of major bleeding and no major infections. There were roughly five device malfunctions per patient-year, but in all cases, patients were able to switch to a backup driver uneventfully.

Twelve of the 13 total patients ultimately underwent transplantation, for a transplantation rate of 92%.

"The Freedom driver is effective in supporting circulation with a total artificial heart. Discharge home is safe and feasible," commented Dr. Kasirajan, who is director of heart transplantation, heart-lung transplantation, and mechanical circulatory support at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

"Further data on the completion of this study will help to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the driver. In addition, important data on exercise capacity and quality of life will be valuable in finally moving the artificial heart technology to more widespread use," he said.

Session comoderator Dr. Todd M. Dewey, a cardiothoracic surgeon with Medical City Specialists in Dallas, noted, "The majority of patients on axial-flow left ventricular assist devices are discharged home. What percentage of total artificial heart patients do you think will ultimately leave the hospital?"

"We are close to 80% of our patients going home right now, at least in high-volume institutions," Dr. Kasirajan replied. Two patients have been at home for more than 2 years without readmissions related to the device, he added.

A pivotal study previously showed that the total artificial heart can be used as a bridge to transplantation in patients with irreversible biventricular failure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:859-67).

"Unfortunately, ... the widespread use of this technology is limited because of the inability to discharge these patients home, and that relates to the fact that the circulatory support system console has to be powered by compressed air either from the hospital or via a cylinder," Dr. Kasirajan explained.

However, once patients are stable, the driver settings need little adjustment, which spurred development of the portable driver. "The driver has two batteries that allow up to 3 hours of untethered activity. These can be charged in place using an alternating current output or car charger," he said.

The ongoing study of the driver will enroll up to 60 patients from 30 international sites. Patients are required to be wait-listed for heart transplantation and receive a total artificial heart, and to be clinically stable on the circulatory support system, with a cardiac index of at least 2.2 L/min/m2. They are then switched to the portable driver with the intent of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Kasirajan reported results for the first 13 patients enrolled from four U.S. sites. Overall, 5 of the patients remained in the hospital (because of medical reasons, discharge logistics, or personal preference), whereas 8 went home with the driver. The median duration out of the hospital in the latter group was 162 days (range, 39-437 days).

The 13 patients had maintenance of cardiac function, with a cardiac index averaging 3.3 L/min/m2, and their laboratory values remained stable between baseline and 90 days. "Particularly, there was no evidence of hemolysis that was worse than at the beginning," he noted. "Increasing albumin levels reflect the increasing nutritional status in these patients."

The in-hospital group had a very similar rate of adverse events relative to an earlier comparison cohort of stable patients with a total artificial heart followed as part of postmarket surveillance, according to Dr. Kasirajan.

Within the study population, the out-of-hospital and in-hospital groups had similar rates of major bleeding (1.1 vs. 1.4 events per patient-year). The former had a lower rate of major infection (0 vs. 2.8 events per patient-year) but higher rates of device malfunction (4.6 vs. 0 events per patient-year) and hemolysis (2.3 vs. 0 events per patient-year).

The five device malfunctions in the out-of-hospital group were due to a Valsalva maneuver, a faulty sensor, hypertension, a kink in the driveline while a patient was getting into a car, and dropping of the driver while showering.

"All these patients remained stable and had no changes in cardiac output," Dr. Kasirajan pointed out. "They were able to switch to the backup driver as educated, and returned to the hospital."

Valsalva maneuvers can cause a sudden transient rise in intrathoracic pressure that a device sensor interprets as outside the set parameters, he explained; the software has since been modified to allow for these changes.

"The importance of hypertension management is critical," he commented. "The pump tolerates blood pressures at high levels for brief periods of time; however, prolonged hypertension leads to a decrease in left heart cardiac output and pulmonary edema."

The cases of hemolysis were due to transient rises in plasma free hemoglobin as a result of hemothorax and hydralazine-induced hemolytic anemia.

Only a single patient, in the out-of-hospital group, died before transplantation. This patient was stable on the driver for 437 days, but experienced a fall with a spinal cord hematoma, and developed fatal complications.

Dr. Kasirajan disclosed that he is a consultant to SynCardia Systems.

LOS ANGELES – Some patients with a total artificial heart can safely go home with the use of a small portable driver while awaiting heart transplantation, according to data from the first U.S. patient cohort in whom this was attempted.

Investigators assessed outcomes in 13 total artificial heart recipients who were stable enough clinically to be transitioned from the usual driver to SynCardia Systems’ investigational portable driver, the Freedom Driver System. The driver weighs 14 pounds and allows several hours of untethered activity.

Eight of the patients were able to go home for an average of 5.5 months, lead investigator Dr. Vigneshwar Kasirajan reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

They had a low rate of major bleeding and no major infections. There were roughly five device malfunctions per patient-year, but in all cases, patients were able to switch to a backup driver uneventfully.

Twelve of the 13 total patients ultimately underwent transplantation, for a transplantation rate of 92%.

"The Freedom driver is effective in supporting circulation with a total artificial heart. Discharge home is safe and feasible," commented Dr. Kasirajan, who is director of heart transplantation, heart-lung transplantation, and mechanical circulatory support at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

"Further data on the completion of this study will help to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the driver. In addition, important data on exercise capacity and quality of life will be valuable in finally moving the artificial heart technology to more widespread use," he said.

Session comoderator Dr. Todd M. Dewey, a cardiothoracic surgeon with Medical City Specialists in Dallas, noted, "The majority of patients on axial-flow left ventricular assist devices are discharged home. What percentage of total artificial heart patients do you think will ultimately leave the hospital?"

"We are close to 80% of our patients going home right now, at least in high-volume institutions," Dr. Kasirajan replied. Two patients have been at home for more than 2 years without readmissions related to the device, he added.

A pivotal study previously showed that the total artificial heart can be used as a bridge to transplantation in patients with irreversible biventricular failure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:859-67).

"Unfortunately, ... the widespread use of this technology is limited because of the inability to discharge these patients home, and that relates to the fact that the circulatory support system console has to be powered by compressed air either from the hospital or via a cylinder," Dr. Kasirajan explained.

However, once patients are stable, the driver settings need little adjustment, which spurred development of the portable driver. "The driver has two batteries that allow up to 3 hours of untethered activity. These can be charged in place using an alternating current output or car charger," he said.

The ongoing study of the driver will enroll up to 60 patients from 30 international sites. Patients are required to be wait-listed for heart transplantation and receive a total artificial heart, and to be clinically stable on the circulatory support system, with a cardiac index of at least 2.2 L/min/m2. They are then switched to the portable driver with the intent of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Kasirajan reported results for the first 13 patients enrolled from four U.S. sites. Overall, 5 of the patients remained in the hospital (because of medical reasons, discharge logistics, or personal preference), whereas 8 went home with the driver. The median duration out of the hospital in the latter group was 162 days (range, 39-437 days).

The 13 patients had maintenance of cardiac function, with a cardiac index averaging 3.3 L/min/m2, and their laboratory values remained stable between baseline and 90 days. "Particularly, there was no evidence of hemolysis that was worse than at the beginning," he noted. "Increasing albumin levels reflect the increasing nutritional status in these patients."

The in-hospital group had a very similar rate of adverse events relative to an earlier comparison cohort of stable patients with a total artificial heart followed as part of postmarket surveillance, according to Dr. Kasirajan.

Within the study population, the out-of-hospital and in-hospital groups had similar rates of major bleeding (1.1 vs. 1.4 events per patient-year). The former had a lower rate of major infection (0 vs. 2.8 events per patient-year) but higher rates of device malfunction (4.6 vs. 0 events per patient-year) and hemolysis (2.3 vs. 0 events per patient-year).

The five device malfunctions in the out-of-hospital group were due to a Valsalva maneuver, a faulty sensor, hypertension, a kink in the driveline while a patient was getting into a car, and dropping of the driver while showering.

"All these patients remained stable and had no changes in cardiac output," Dr. Kasirajan pointed out. "They were able to switch to the backup driver as educated, and returned to the hospital."

Valsalva maneuvers can cause a sudden transient rise in intrathoracic pressure that a device sensor interprets as outside the set parameters, he explained; the software has since been modified to allow for these changes.

"The importance of hypertension management is critical," he commented. "The pump tolerates blood pressures at high levels for brief periods of time; however, prolonged hypertension leads to a decrease in left heart cardiac output and pulmonary edema."

The cases of hemolysis were due to transient rises in plasma free hemoglobin as a result of hemothorax and hydralazine-induced hemolytic anemia.

Only a single patient, in the out-of-hospital group, died before transplantation. This patient was stable on the driver for 437 days, but experienced a fall with a spinal cord hematoma, and developed fatal complications.

Dr. Kasirajan disclosed that he is a consultant to SynCardia Systems.

LOS ANGELES – Some patients with a total artificial heart can safely go home with the use of a small portable driver while awaiting heart transplantation, according to data from the first U.S. patient cohort in whom this was attempted.

Investigators assessed outcomes in 13 total artificial heart recipients who were stable enough clinically to be transitioned from the usual driver to SynCardia Systems’ investigational portable driver, the Freedom Driver System. The driver weighs 14 pounds and allows several hours of untethered activity.

Eight of the patients were able to go home for an average of 5.5 months, lead investigator Dr. Vigneshwar Kasirajan reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

They had a low rate of major bleeding and no major infections. There were roughly five device malfunctions per patient-year, but in all cases, patients were able to switch to a backup driver uneventfully.

Twelve of the 13 total patients ultimately underwent transplantation, for a transplantation rate of 92%.

"The Freedom driver is effective in supporting circulation with a total artificial heart. Discharge home is safe and feasible," commented Dr. Kasirajan, who is director of heart transplantation, heart-lung transplantation, and mechanical circulatory support at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

"Further data on the completion of this study will help to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the driver. In addition, important data on exercise capacity and quality of life will be valuable in finally moving the artificial heart technology to more widespread use," he said.

Session comoderator Dr. Todd M. Dewey, a cardiothoracic surgeon with Medical City Specialists in Dallas, noted, "The majority of patients on axial-flow left ventricular assist devices are discharged home. What percentage of total artificial heart patients do you think will ultimately leave the hospital?"

"We are close to 80% of our patients going home right now, at least in high-volume institutions," Dr. Kasirajan replied. Two patients have been at home for more than 2 years without readmissions related to the device, he added.

A pivotal study previously showed that the total artificial heart can be used as a bridge to transplantation in patients with irreversible biventricular failure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:859-67).

"Unfortunately, ... the widespread use of this technology is limited because of the inability to discharge these patients home, and that relates to the fact that the circulatory support system console has to be powered by compressed air either from the hospital or via a cylinder," Dr. Kasirajan explained.

However, once patients are stable, the driver settings need little adjustment, which spurred development of the portable driver. "The driver has two batteries that allow up to 3 hours of untethered activity. These can be charged in place using an alternating current output or car charger," he said.

The ongoing study of the driver will enroll up to 60 patients from 30 international sites. Patients are required to be wait-listed for heart transplantation and receive a total artificial heart, and to be clinically stable on the circulatory support system, with a cardiac index of at least 2.2 L/min/m2. They are then switched to the portable driver with the intent of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Kasirajan reported results for the first 13 patients enrolled from four U.S. sites. Overall, 5 of the patients remained in the hospital (because of medical reasons, discharge logistics, or personal preference), whereas 8 went home with the driver. The median duration out of the hospital in the latter group was 162 days (range, 39-437 days).

The 13 patients had maintenance of cardiac function, with a cardiac index averaging 3.3 L/min/m2, and their laboratory values remained stable between baseline and 90 days. "Particularly, there was no evidence of hemolysis that was worse than at the beginning," he noted. "Increasing albumin levels reflect the increasing nutritional status in these patients."

The in-hospital group had a very similar rate of adverse events relative to an earlier comparison cohort of stable patients with a total artificial heart followed as part of postmarket surveillance, according to Dr. Kasirajan.

Within the study population, the out-of-hospital and in-hospital groups had similar rates of major bleeding (1.1 vs. 1.4 events per patient-year). The former had a lower rate of major infection (0 vs. 2.8 events per patient-year) but higher rates of device malfunction (4.6 vs. 0 events per patient-year) and hemolysis (2.3 vs. 0 events per patient-year).

The five device malfunctions in the out-of-hospital group were due to a Valsalva maneuver, a faulty sensor, hypertension, a kink in the driveline while a patient was getting into a car, and dropping of the driver while showering.

"All these patients remained stable and had no changes in cardiac output," Dr. Kasirajan pointed out. "They were able to switch to the backup driver as educated, and returned to the hospital."

Valsalva maneuvers can cause a sudden transient rise in intrathoracic pressure that a device sensor interprets as outside the set parameters, he explained; the software has since been modified to allow for these changes.

"The importance of hypertension management is critical," he commented. "The pump tolerates blood pressures at high levels for brief periods of time; however, prolonged hypertension leads to a decrease in left heart cardiac output and pulmonary edema."

The cases of hemolysis were due to transient rises in plasma free hemoglobin as a result of hemothorax and hydralazine-induced hemolytic anemia.

Only a single patient, in the out-of-hospital group, died before transplantation. This patient was stable on the driver for 437 days, but experienced a fall with a spinal cord hematoma, and developed fatal complications.

Dr. Kasirajan disclosed that he is a consultant to SynCardia Systems.

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: The eight patients who were able to go home had a low rate of major bleeding and no major infections. The rate of device malfunctions was 4.6 events per patient-year, but none of these patients experienced a change in cardiac output.

Data source: An interim analysis of a cohort study among 13 clinically stable patients with a total artificial heart powered by a portable driver.

Disclosures: Dr. Kasirajan disclosed that he is a consultant to SynCardia Systems.

Everolimus approval now includes prevention of liver transplant rejection

Food and Drug Administration approval of the immunosuppressant drug everolimus has been expanded to include prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a liver transplant.

The approval, on Feb. 15, was announced by the manufacturer, Novartis. Everolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, was first approved for prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a kidney transplant in 2010, and is taken twice a day by mouth.

The approved indication states that in liver transplant recipients, everolimus is used in combination with the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus (at a reduced dose) and corticosteroids, and that it should be administered no earlier than 30 days post transplant. Safety and efficacy have not been established in pediatric patients, according to the prescribing information.

FDA approval was based on the 12-month results of a phase III, open-label international study of 719 liver transplant recipients (mean age, 54 years). At 12 months, the rate of the "efficacy failure" endpoint (defined as biopsy-proven acute rejection, graft loss, death, or loss to follow-up) was "comparable" between those patients treated with the reduced dose of everolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (9%), and the patients treated with the standard dose of tacrolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (13.6%), according to the Novartis statement and prescribing information. All patients were treated with corticosteroids.

Everolimus is the first mTOR inhibitor approved for liver transplant recipients, and is the first immunosuppressant approved by the FDA for use in liver transplant recipients in more than 10 years, according to Novartis.

Novartis markets everolimus in the United States as Zortress. It was approved in the European Union in the fourth quarter of 2012 for adult liver transplant recipients; it is marketed as Certican in Europe.

The new label is available here. Serious adverse events associated with everolimus should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Food and Drug Administration approval of the immunosuppressant drug everolimus has been expanded to include prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a liver transplant.

The approval, on Feb. 15, was announced by the manufacturer, Novartis. Everolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, was first approved for prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a kidney transplant in 2010, and is taken twice a day by mouth.

The approved indication states that in liver transplant recipients, everolimus is used in combination with the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus (at a reduced dose) and corticosteroids, and that it should be administered no earlier than 30 days post transplant. Safety and efficacy have not been established in pediatric patients, according to the prescribing information.

FDA approval was based on the 12-month results of a phase III, open-label international study of 719 liver transplant recipients (mean age, 54 years). At 12 months, the rate of the "efficacy failure" endpoint (defined as biopsy-proven acute rejection, graft loss, death, or loss to follow-up) was "comparable" between those patients treated with the reduced dose of everolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (9%), and the patients treated with the standard dose of tacrolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (13.6%), according to the Novartis statement and prescribing information. All patients were treated with corticosteroids.

Everolimus is the first mTOR inhibitor approved for liver transplant recipients, and is the first immunosuppressant approved by the FDA for use in liver transplant recipients in more than 10 years, according to Novartis.

Novartis markets everolimus in the United States as Zortress. It was approved in the European Union in the fourth quarter of 2012 for adult liver transplant recipients; it is marketed as Certican in Europe.

The new label is available here. Serious adverse events associated with everolimus should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Food and Drug Administration approval of the immunosuppressant drug everolimus has been expanded to include prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a liver transplant.

The approval, on Feb. 15, was announced by the manufacturer, Novartis. Everolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, was first approved for prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults undergoing a kidney transplant in 2010, and is taken twice a day by mouth.

The approved indication states that in liver transplant recipients, everolimus is used in combination with the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus (at a reduced dose) and corticosteroids, and that it should be administered no earlier than 30 days post transplant. Safety and efficacy have not been established in pediatric patients, according to the prescribing information.

FDA approval was based on the 12-month results of a phase III, open-label international study of 719 liver transplant recipients (mean age, 54 years). At 12 months, the rate of the "efficacy failure" endpoint (defined as biopsy-proven acute rejection, graft loss, death, or loss to follow-up) was "comparable" between those patients treated with the reduced dose of everolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (9%), and the patients treated with the standard dose of tacrolimus, started 30 days after transplantation (13.6%), according to the Novartis statement and prescribing information. All patients were treated with corticosteroids.

Everolimus is the first mTOR inhibitor approved for liver transplant recipients, and is the first immunosuppressant approved by the FDA for use in liver transplant recipients in more than 10 years, according to Novartis.

Novartis markets everolimus in the United States as Zortress. It was approved in the European Union in the fourth quarter of 2012 for adult liver transplant recipients; it is marketed as Certican in Europe.

The new label is available here. Serious adverse events associated with everolimus should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Survey: Most support transfusing to increase organ donation

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EAST ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: Among respondents, 72.5% agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury for the sake of organ donation, but there was less consensus on when and how to manage these patients.

Data Source: Electronic survey of 285 trauma surgeons in the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Disclosures: Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

No early cancer risk with donor lungs from heavy smokers

LOS ANGELES – Use of lungs from donors who smoked heavily does not worsen lung transplantation outcomes including risk for lung cancer death, at least in the medium term.

At a median follow-up of 2 years for 5,900 adults who had double-lung transplants, those who received lungs from heavy smokers had an actuarial median overall survival of roughly 5.5 years, and their lung function was essentially the same as that of patients who received lungs from other donors, Dr. Sharven Taghavi reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The study data came from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. A team led by Dr. Taghavi, of Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, compared data for double-lung transplants from 2005-2011, comparing donors with a history of smoking exceeding 20 pack-years with other donors.

About 13% of the study patients received lungs from donors who had smoked heavily. Compared with other recipients, these recipients were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and less likely to have a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Otherwise, they were similar.

The rate of deaths due to cancer was based on case reports, as UNOS does not capture this outcome. Cancer deaths were 5.8% among recipients of lungs from heavy smokers and 3.6% among other recipients.

"There is a fairly low capture rate for this field, so it’s difficult to draw significant conclusions from it," cautioned Dr. Taghavi.

Patients who received lungs from heavy smokers had a 1-day longer length of stay in the hospital (18 days vs. 17 days), which "may not really be clinically relevant." Rates of acute rejection during hospitalization were comparable (10.7% vs. 8.8%), as was post-transplant airway dehiscence (1.8% vs. 1.8%).

Post-transplant peak forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was the same (80% vs. 79%), as was decline in this measure over time. Median duration of freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome was 1,583 days vs. 1,827 days.

Risk-adjusted median all-cause survival – the study’s primary endpoint – did not differ significantly between the recipients given lungs from donors who smoked heavily and the other recipients (2,043 vs. 1,928 days).

The rate of cancer deaths did not differ significantly; however, the follow-up time is too short to address this concern in a meaningful way, Dr. Taghavi said.

"Currently, we recommend when evaluating a donor who has a heavy smoking history, that they undergo a thorough examination for lung tumors or evidence of cancer. This includes obtaining a chest x-ray, CT scans, and bronchoscopies. In addition, when the lungs are procured, they should undergo a very thorough visual inspection," he advised.

"Informed consent is very important. You have to discuss the donor’s smoking status with the recipient and explain the risks and the benefits," Dr. Taghavi said. Lung cancer risk, given the donor’s history, is about 1% to 2% annually, and that needs to be considered against the high likelihood of dying within 1 or 2 years without a transplant.

"One thing that is unquestionable is that survival will be better accepting these lungs than it will be sitting on a waiting list," he added. Only about half of the people listed for lung transplant in the United States each year actually undergo the surgery.

Recipients of lungs from heavy smokers do not need any extra follow-up or surveillance, as they are already diligently tested and monitored, according to Dr. Taghavi. The recipient’s immunosuppression does theoretically put one at additional risk for lung cancer.

Current guidelines of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation advise against considering use of lungs from donors who have a smoking history of more than 20 pack-years, Dr. Taghavi noted. But he stopped short of saying that the study should prompt a formal revision of those guidelines.

"I think the findings start the conversation," he commented. "We should consider looking at these potential donors," especially when a recipient’s situation is dire.

Dr. Taghavi disclosed no conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Use of lungs from donors who smoked heavily does not worsen lung transplantation outcomes including risk for lung cancer death, at least in the medium term.

At a median follow-up of 2 years for 5,900 adults who had double-lung transplants, those who received lungs from heavy smokers had an actuarial median overall survival of roughly 5.5 years, and their lung function was essentially the same as that of patients who received lungs from other donors, Dr. Sharven Taghavi reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The study data came from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. A team led by Dr. Taghavi, of Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, compared data for double-lung transplants from 2005-2011, comparing donors with a history of smoking exceeding 20 pack-years with other donors.

About 13% of the study patients received lungs from donors who had smoked heavily. Compared with other recipients, these recipients were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and less likely to have a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Otherwise, they were similar.

The rate of deaths due to cancer was based on case reports, as UNOS does not capture this outcome. Cancer deaths were 5.8% among recipients of lungs from heavy smokers and 3.6% among other recipients.

"There is a fairly low capture rate for this field, so it’s difficult to draw significant conclusions from it," cautioned Dr. Taghavi.

Patients who received lungs from heavy smokers had a 1-day longer length of stay in the hospital (18 days vs. 17 days), which "may not really be clinically relevant." Rates of acute rejection during hospitalization were comparable (10.7% vs. 8.8%), as was post-transplant airway dehiscence (1.8% vs. 1.8%).

Post-transplant peak forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was the same (80% vs. 79%), as was decline in this measure over time. Median duration of freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome was 1,583 days vs. 1,827 days.

Risk-adjusted median all-cause survival – the study’s primary endpoint – did not differ significantly between the recipients given lungs from donors who smoked heavily and the other recipients (2,043 vs. 1,928 days).

The rate of cancer deaths did not differ significantly; however, the follow-up time is too short to address this concern in a meaningful way, Dr. Taghavi said.

"Currently, we recommend when evaluating a donor who has a heavy smoking history, that they undergo a thorough examination for lung tumors or evidence of cancer. This includes obtaining a chest x-ray, CT scans, and bronchoscopies. In addition, when the lungs are procured, they should undergo a very thorough visual inspection," he advised.

"Informed consent is very important. You have to discuss the donor’s smoking status with the recipient and explain the risks and the benefits," Dr. Taghavi said. Lung cancer risk, given the donor’s history, is about 1% to 2% annually, and that needs to be considered against the high likelihood of dying within 1 or 2 years without a transplant.

"One thing that is unquestionable is that survival will be better accepting these lungs than it will be sitting on a waiting list," he added. Only about half of the people listed for lung transplant in the United States each year actually undergo the surgery.

Recipients of lungs from heavy smokers do not need any extra follow-up or surveillance, as they are already diligently tested and monitored, according to Dr. Taghavi. The recipient’s immunosuppression does theoretically put one at additional risk for lung cancer.

Current guidelines of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation advise against considering use of lungs from donors who have a smoking history of more than 20 pack-years, Dr. Taghavi noted. But he stopped short of saying that the study should prompt a formal revision of those guidelines.

"I think the findings start the conversation," he commented. "We should consider looking at these potential donors," especially when a recipient’s situation is dire.

Dr. Taghavi disclosed no conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Use of lungs from donors who smoked heavily does not worsen lung transplantation outcomes including risk for lung cancer death, at least in the medium term.

At a median follow-up of 2 years for 5,900 adults who had double-lung transplants, those who received lungs from heavy smokers had an actuarial median overall survival of roughly 5.5 years, and their lung function was essentially the same as that of patients who received lungs from other donors, Dr. Sharven Taghavi reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The study data came from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. A team led by Dr. Taghavi, of Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, compared data for double-lung transplants from 2005-2011, comparing donors with a history of smoking exceeding 20 pack-years with other donors.

About 13% of the study patients received lungs from donors who had smoked heavily. Compared with other recipients, these recipients were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and less likely to have a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Otherwise, they were similar.

The rate of deaths due to cancer was based on case reports, as UNOS does not capture this outcome. Cancer deaths were 5.8% among recipients of lungs from heavy smokers and 3.6% among other recipients.

"There is a fairly low capture rate for this field, so it’s difficult to draw significant conclusions from it," cautioned Dr. Taghavi.

Patients who received lungs from heavy smokers had a 1-day longer length of stay in the hospital (18 days vs. 17 days), which "may not really be clinically relevant." Rates of acute rejection during hospitalization were comparable (10.7% vs. 8.8%), as was post-transplant airway dehiscence (1.8% vs. 1.8%).

Post-transplant peak forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was the same (80% vs. 79%), as was decline in this measure over time. Median duration of freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome was 1,583 days vs. 1,827 days.

Risk-adjusted median all-cause survival – the study’s primary endpoint – did not differ significantly between the recipients given lungs from donors who smoked heavily and the other recipients (2,043 vs. 1,928 days).

The rate of cancer deaths did not differ significantly; however, the follow-up time is too short to address this concern in a meaningful way, Dr. Taghavi said.

"Currently, we recommend when evaluating a donor who has a heavy smoking history, that they undergo a thorough examination for lung tumors or evidence of cancer. This includes obtaining a chest x-ray, CT scans, and bronchoscopies. In addition, when the lungs are procured, they should undergo a very thorough visual inspection," he advised.

"Informed consent is very important. You have to discuss the donor’s smoking status with the recipient and explain the risks and the benefits," Dr. Taghavi said. Lung cancer risk, given the donor’s history, is about 1% to 2% annually, and that needs to be considered against the high likelihood of dying within 1 or 2 years without a transplant.

"One thing that is unquestionable is that survival will be better accepting these lungs than it will be sitting on a waiting list," he added. Only about half of the people listed for lung transplant in the United States each year actually undergo the surgery.

Recipients of lungs from heavy smokers do not need any extra follow-up or surveillance, as they are already diligently tested and monitored, according to Dr. Taghavi. The recipient’s immunosuppression does theoretically put one at additional risk for lung cancer.

Current guidelines of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation advise against considering use of lungs from donors who have a smoking history of more than 20 pack-years, Dr. Taghavi noted. But he stopped short of saying that the study should prompt a formal revision of those guidelines.

"I think the findings start the conversation," he commented. "We should consider looking at these potential donors," especially when a recipient’s situation is dire.

Dr. Taghavi disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF THROACIC SURGEONS

Major Finding: Risk-adjusted median all-cause survival did not differ significantly between patients given lungs from donors who smoked heavily and those receiving lungs from donors who did not smoke heavily (2,043 vs. 1,928 days).

Data Source: An observational cohort study of 5,900 adult primary double-lung transplant recipients in the UNOS database

Disclosures: Dr. Taghavi disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

New approaches expand kidney transplant pool

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Renal transplant surgeons are using novel methods to expand the pool of donor organs: Using kidneys from donors with acute kidney injury, and vetting and improving the function of kidneys by applying pulsatile machine perfusion to stored kidneys pending transplant.

These approaches can overlap, as machine perfusion has become an important tool for improving the function of kidneys from donors with acute kidney injury (AKI) as well as other marginal kidneys such as those from extended-criteria donors and donation after cardiac death.

Surgeons at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., began transplanting kidneys from AKI donors in 2007, and by mid-2012 they had placed 84 of these organs, resulting in actuarial 5-year patient-survival and graft-survival rates that matched transplants during the same period with kidneys from non-AKI donors, Dr. Alan C. Farney said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Seventy-four of these kidneys (88%) underwent machine perfusion, for a minimum of 6 hours and more often overnight, said Dr. Farney’s colleague, Dr. Robert J. Stratta, professor of surgery at Wake Forest. "We try to pump whenever possible, and in a perfect world we’d like to see all kidneys pumped" before they are transplanted, Dr. Stratta said. In addition to improving function, mechanical perfusion allows surgeons to assess kidney function. If resistance in the kidney is more than 0.4 or 0.5 mm Hg/mL per minute, "we tend to discard it," he noted.

A second report at the meeting further documented the ability of mechanical perfusion to boost kidney function. In a review of more than 50,000 adult, isolated kidney transplants done on American patients during January 2005–March 2011, machine perfusion prior to transplant led to an average 8-percentage-point cut in the rate of delayed kidney function in a pair of analyses that accounted for baseline patient differences. This means that every 13 kidneys treated before transplant with mechanical perfusion prevented a case of delayed graft function (DGF) following transplantation, resulting in fewer patients requiring hemodialysis, Dr. Glen A. Franklin reported at the meeting.

Prevention of DGF mitigates edema, reduces the need for wound drainage, and decreases the risk for infection, factors that – along with the need for dialysis – drive up costs. Preventing these complications and their associated costs potentially offsets the extra expense of routinely perfusing each kidney before transplantation, Dr. Stratta said.

Dr. Stratta and his associates reviewed the outcomes of 84 transplants of kidneys from donors with AKI done at Wake Forest since 2007 and compared this against the outcomes of 283 concurrent kidney transplants performed during the same 2007-2012 period using organs from donors without AKI. A major, statistically significant difference in protocol for the two types of organs was that 88% of the AKI-derived kidneys underwent machine perfusion before transplant, compared with 51% of the kidneys that came from non-AKI donors, reported Dr. Farney, professor of surgery at Wake Forest.

A major difference in outcomes was that the incidence of DGF following transplantation occurred in 41% of patients who received a kidney from an AKI donor, compared with a 27% DGF rate among patients whose kidneys came from non-AKI donors, a statistically-significant difference.

Despite this, actuarial 5-year patient survival was 98% among the AKI kidney recipients and 90% among the non-AKI kidney recipients. Five-year graft survival was 78% in the AKI-kidney recipients and 71% in patients who received a non-AKI organ. The between-group differences were not statistically significant, Dr. Farney said.

The data also showed an unexpected difference in the way that DGF appeared to affect graft survival. Among patients whose kidneys came from non-AKI donors, the 5-year graft survival rate was 90% among the 206 patients who did not have DGF, but fell to 68% among the 77 patients in this group who had DGF, a statistically-significant difference. In contrast, among patients who received kidneys from AKI donors, the incidence of DGF had no significant impact on long-term graft survival.