User login

Less pain, quicker discharge with post-TORS dexamethasone

SEATTLE – A longer course of dexamethasone was a bit better than the usual single intraoperative dose for controlling pain and dysphagia after transoral robotic surgery in a randomized trial from the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Thirty-five subjects were randomized to the standard 10-mg intraoperative dexamethasone dose plus 8 mg every 8 hours for up to 4 days; 33 others were randomized to the intraoperative dose plus placebo. All the subjects had transoral robotic surgery (TORS) resection for T1 or T2 oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, either partial pharyngectomy/radical tonsillectomy, base of tongue resection, or both.

The dexamethasone group had significantly less pain on postop day 3 (about 1.5 points less on the 10-point visual analogue scale) and were discharged, on average, a day earlier. They also advanced more quickly toward solid food at 1- and 3-weeks’ follow-up. “They were much more likely to be on a full-soft diet, while the placebo group was mostly still on purees, and just starting into soft foods,” said lead investigator Daniel Clayburgh, MD, a head and neck cancer specialist at the university.

Otherwise, however, the extra dexamethasone wasn’t much help; pain scores were the same in both groups for the first couple days after surgery and at follow-up, and both groups used the same amount of post-op opioids. Other than food tolerance, dysphagia metrics were pretty much the same.

“I was actually anticipating a little bit more of a benefit, but there are potentially some benefits to extended corticosteroid courses after TORS. It’s safe, and well tolerated so long as you screen out diabetes and other problems with hyperglycemia,” as was done in the study, he said. “It does decrease post-op length of stay and may provide a modest decrease in post-op pain, and may slightly accelerate advancement of dietary consistency,” Dr. Clayburgh said at the International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, held by the American Head and Neck Society.

Although he and his colleagues are mulling over what to do with the findings in light of other initiatives to reduce post-TORS pain, they are now likely to extend dexamethasone courses when significant post-op pain seems likely, and doing so is not otherwise contraindicated, he said.

Intraoperative corticosteroids are now routine for TORS, based on the strength of benefit in the tonsillectomy literature. The team decided to try an extended course because “being rather simple minded surgeons, we thought that if one dose is good, more should be better,” Dr. Clayburgh said.

The dexamethasone group was slightly younger than the placebo group (56 vs. 61 years) but otherwise similar; most were men. In addition to patients with hyperglycemia issues, those with confounders for post-op speech and swallowing recovery were among those excluded from the trial. Subjects required nasogastric feeding tubes for a median of 6.5 days postoperatively, lost a mean of 10 pounds in the first 2 post-op weeks, and were hospitalized for a mean of about 5 days. Dexamethasone was delivered orally or by nasogastric tube.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Clayburgh had no relevant financial disclosures.

SEATTLE – A longer course of dexamethasone was a bit better than the usual single intraoperative dose for controlling pain and dysphagia after transoral robotic surgery in a randomized trial from the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Thirty-five subjects were randomized to the standard 10-mg intraoperative dexamethasone dose plus 8 mg every 8 hours for up to 4 days; 33 others were randomized to the intraoperative dose plus placebo. All the subjects had transoral robotic surgery (TORS) resection for T1 or T2 oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, either partial pharyngectomy/radical tonsillectomy, base of tongue resection, or both.

The dexamethasone group had significantly less pain on postop day 3 (about 1.5 points less on the 10-point visual analogue scale) and were discharged, on average, a day earlier. They also advanced more quickly toward solid food at 1- and 3-weeks’ follow-up. “They were much more likely to be on a full-soft diet, while the placebo group was mostly still on purees, and just starting into soft foods,” said lead investigator Daniel Clayburgh, MD, a head and neck cancer specialist at the university.

Otherwise, however, the extra dexamethasone wasn’t much help; pain scores were the same in both groups for the first couple days after surgery and at follow-up, and both groups used the same amount of post-op opioids. Other than food tolerance, dysphagia metrics were pretty much the same.

“I was actually anticipating a little bit more of a benefit, but there are potentially some benefits to extended corticosteroid courses after TORS. It’s safe, and well tolerated so long as you screen out diabetes and other problems with hyperglycemia,” as was done in the study, he said. “It does decrease post-op length of stay and may provide a modest decrease in post-op pain, and may slightly accelerate advancement of dietary consistency,” Dr. Clayburgh said at the International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, held by the American Head and Neck Society.

Although he and his colleagues are mulling over what to do with the findings in light of other initiatives to reduce post-TORS pain, they are now likely to extend dexamethasone courses when significant post-op pain seems likely, and doing so is not otherwise contraindicated, he said.

Intraoperative corticosteroids are now routine for TORS, based on the strength of benefit in the tonsillectomy literature. The team decided to try an extended course because “being rather simple minded surgeons, we thought that if one dose is good, more should be better,” Dr. Clayburgh said.

The dexamethasone group was slightly younger than the placebo group (56 vs. 61 years) but otherwise similar; most were men. In addition to patients with hyperglycemia issues, those with confounders for post-op speech and swallowing recovery were among those excluded from the trial. Subjects required nasogastric feeding tubes for a median of 6.5 days postoperatively, lost a mean of 10 pounds in the first 2 post-op weeks, and were hospitalized for a mean of about 5 days. Dexamethasone was delivered orally or by nasogastric tube.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Clayburgh had no relevant financial disclosures.

SEATTLE – A longer course of dexamethasone was a bit better than the usual single intraoperative dose for controlling pain and dysphagia after transoral robotic surgery in a randomized trial from the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Thirty-five subjects were randomized to the standard 10-mg intraoperative dexamethasone dose plus 8 mg every 8 hours for up to 4 days; 33 others were randomized to the intraoperative dose plus placebo. All the subjects had transoral robotic surgery (TORS) resection for T1 or T2 oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, either partial pharyngectomy/radical tonsillectomy, base of tongue resection, or both.

The dexamethasone group had significantly less pain on postop day 3 (about 1.5 points less on the 10-point visual analogue scale) and were discharged, on average, a day earlier. They also advanced more quickly toward solid food at 1- and 3-weeks’ follow-up. “They were much more likely to be on a full-soft diet, while the placebo group was mostly still on purees, and just starting into soft foods,” said lead investigator Daniel Clayburgh, MD, a head and neck cancer specialist at the university.

Otherwise, however, the extra dexamethasone wasn’t much help; pain scores were the same in both groups for the first couple days after surgery and at follow-up, and both groups used the same amount of post-op opioids. Other than food tolerance, dysphagia metrics were pretty much the same.

“I was actually anticipating a little bit more of a benefit, but there are potentially some benefits to extended corticosteroid courses after TORS. It’s safe, and well tolerated so long as you screen out diabetes and other problems with hyperglycemia,” as was done in the study, he said. “It does decrease post-op length of stay and may provide a modest decrease in post-op pain, and may slightly accelerate advancement of dietary consistency,” Dr. Clayburgh said at the International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, held by the American Head and Neck Society.

Although he and his colleagues are mulling over what to do with the findings in light of other initiatives to reduce post-TORS pain, they are now likely to extend dexamethasone courses when significant post-op pain seems likely, and doing so is not otherwise contraindicated, he said.

Intraoperative corticosteroids are now routine for TORS, based on the strength of benefit in the tonsillectomy literature. The team decided to try an extended course because “being rather simple minded surgeons, we thought that if one dose is good, more should be better,” Dr. Clayburgh said.

The dexamethasone group was slightly younger than the placebo group (56 vs. 61 years) but otherwise similar; most were men. In addition to patients with hyperglycemia issues, those with confounders for post-op speech and swallowing recovery were among those excluded from the trial. Subjects required nasogastric feeding tubes for a median of 6.5 days postoperatively, lost a mean of 10 pounds in the first 2 post-op weeks, and were hospitalized for a mean of about 5 days. Dexamethasone was delivered orally or by nasogastric tube.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Clayburgh had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AHNS 2016

Key clinical point: A longer course of dexamethasone is a bit better than the usual single intraoperative dose for controlling pain and dysphagia after transoral robotic surgery.

Major finding: The dexamethasone group had significantly less pain on post-op day 3 (about 1.5 points less on the 10-point visual analogue scale) and were discharged, on average, a day earlier. They also advanced more quickly toward solid food at 1- and 3-weeks’ follow-up.

Data source: A randomized trial of 68 TORS patients.

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the study, and the lead investigator had no relevant financial disclosures.

Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery performed mostly by and for white males

BOSTON – Patients who receive robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery (RALS), an increasingly widespread facet of surgical medicine, tend to be higher income white males, according to an extensive new study presented at Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“We wanted to look at how the technology is rolling out ... and what some of those characteristics are that are occurring, not only with the types of patients that are picking up these surgeries but also who the surgeons are that are performing these surgeries,” the study’s lead investigator, Michael A. Palese, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System, New York, explained during a video interview.

A total of 63,725 RALS cases were included, all of which occurred during 2009-2015. In addition to affluent white males being the predominant recipients of this type of surgery, younger white male surgeons tended to be the ones more likely to perform RALS. Across specialties, RALS use has increased substantially over the study period, with the largest increases seen among cardiothoracic surgeons (from 197 cases, 3.1% of all cases per year, to 1,159, 8.7% of all cases). Among general surgeons, RALS use increased from 98 cases (3.2%) to 2,559 cases (19.1%), and for orthopedic surgeons, 55 (0.8%) to 985 (7.4%).

Dr. Palese discussed the genesis of the study, the importance of the study’s findings, and where he foresees RALS heading in the near future. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Patients who receive robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery (RALS), an increasingly widespread facet of surgical medicine, tend to be higher income white males, according to an extensive new study presented at Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“We wanted to look at how the technology is rolling out ... and what some of those characteristics are that are occurring, not only with the types of patients that are picking up these surgeries but also who the surgeons are that are performing these surgeries,” the study’s lead investigator, Michael A. Palese, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System, New York, explained during a video interview.

A total of 63,725 RALS cases were included, all of which occurred during 2009-2015. In addition to affluent white males being the predominant recipients of this type of surgery, younger white male surgeons tended to be the ones more likely to perform RALS. Across specialties, RALS use has increased substantially over the study period, with the largest increases seen among cardiothoracic surgeons (from 197 cases, 3.1% of all cases per year, to 1,159, 8.7% of all cases). Among general surgeons, RALS use increased from 98 cases (3.2%) to 2,559 cases (19.1%), and for orthopedic surgeons, 55 (0.8%) to 985 (7.4%).

Dr. Palese discussed the genesis of the study, the importance of the study’s findings, and where he foresees RALS heading in the near future. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Patients who receive robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery (RALS), an increasingly widespread facet of surgical medicine, tend to be higher income white males, according to an extensive new study presented at Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“We wanted to look at how the technology is rolling out ... and what some of those characteristics are that are occurring, not only with the types of patients that are picking up these surgeries but also who the surgeons are that are performing these surgeries,” the study’s lead investigator, Michael A. Palese, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System, New York, explained during a video interview.

A total of 63,725 RALS cases were included, all of which occurred during 2009-2015. In addition to affluent white males being the predominant recipients of this type of surgery, younger white male surgeons tended to be the ones more likely to perform RALS. Across specialties, RALS use has increased substantially over the study period, with the largest increases seen among cardiothoracic surgeons (from 197 cases, 3.1% of all cases per year, to 1,159, 8.7% of all cases). Among general surgeons, RALS use increased from 98 cases (3.2%) to 2,559 cases (19.1%), and for orthopedic surgeons, 55 (0.8%) to 985 (7.4%).

Dr. Palese discussed the genesis of the study, the importance of the study’s findings, and where he foresees RALS heading in the near future. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY WEEK

Post-TORS neck dissections extend hospital stay

SEATTLE – Oncologic transoral robotic surgery patients spend less time in the hospital if they have neck dissections at the same time, instead of later, according to a review of 441 patients by Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The average hospital length of stay (LOS) was 6 days for the 349 patients (79.1%) who had lymphadenectomy neck dissections at the same time as transoral robotic surgery (TORS). The 92 patients (20.9%) who had staged procedures - neck dissections and TORS about a month apart, with TORS usually done first - stayed in the hospital an average of 8 days (P less than .0001). After risk adjustment, LOS was 43% shorter for concurrent dissections.

Cardiac arrhythmias were also more common in staged patients, perhaps because they had general anesthesia twice in a short period or maybe because staged patients were more likely to be obese (18.5% vs. 7.5%; P less than .01).

However, there were no statistically significant outcome differences otherwise, and the investigators concluded that “concurrent and staged procedures are equally safe. It is therefore reasonable to allow operator preference and patient factors to determine surgical logistics.”

Neck dissection timing has been controversial since the advent of TORS several years ago, when surgeons and administrators realized they could fit more cases into the schedule by doing neck dissections, which can take a few hours, at a different time.

Proponents of the staged approach argue, among other things, that it reduces the risk of fistulas and tracheotomies, and allows surgeons a second go at positive margins. Advocates of concurrent procedures counter that fistulas, if found, can be repaired right away, and that same-time surgery saves money, allows for earlier adjuvant therapy, and cuts anesthesia risks.

There hasn’t been much data to settle the debate, and no one has compared LOS before, so it was “important” to look into the matter, lead investigator Catherine Frenkel, MD, a Stony Brook general surgery resident, said at the American Head and Neck Society International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer.

German investigators also recently concluded that it’s pretty much a draw between concurrent and staged dissections. In a study of 41 TORS cases, “the timing of neck dissection did not make a significant difference in the outcomes. We suggest, therefore, that aspiring and established TORS teams do not restrict their appropriate indications due to robotic slot and theatre time constraints, but perform each indicated TORS case as soon as possible within their given systems, even if the neck dissections cannot be done on the same day,” they said (Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 Jun;41[6]:773-8).

In addition to obese patients, those who had tongue or tonsil lesions were more likely to be staged in the Stony Brook analysis. About half of the surgeons in the study stuck solely to concurrent procedures, while a handful opted for the staged approach, and the rest did both. Perhaps not surprisingly, high-volume surgeons – those who did five or more TORS cases per year – were more likely to stage.

Almost two-thirds of patients had at least one complication, most commonly renal failure, heart problems, extended ventilation, and surgical errors, which included accidental punctures, postop fistulas, hemorrhages, and wound complications. A total of 13% of patients had at least one postop readmission. Apart from arrhythmias, there were no statistically significant differences in complication or 30-day readmission rates between concurrent and staged patients. High-volume surgeons were less likely to have complications.

Postop bleeding was another common problem, and more likely with staged surgeries (12% vs. 7%). Concurrent procedures had a slightly higher rate of new tracheotomies and gastrostomies, but again the differences were not statistically significant, even with pedicle and free-flap reconstruction. There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Oncologic transoral robotic surgery patients spend less time in the hospital if they have neck dissections at the same time, instead of later, according to a review of 441 patients by Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The average hospital length of stay (LOS) was 6 days for the 349 patients (79.1%) who had lymphadenectomy neck dissections at the same time as transoral robotic surgery (TORS). The 92 patients (20.9%) who had staged procedures - neck dissections and TORS about a month apart, with TORS usually done first - stayed in the hospital an average of 8 days (P less than .0001). After risk adjustment, LOS was 43% shorter for concurrent dissections.

Cardiac arrhythmias were also more common in staged patients, perhaps because they had general anesthesia twice in a short period or maybe because staged patients were more likely to be obese (18.5% vs. 7.5%; P less than .01).

However, there were no statistically significant outcome differences otherwise, and the investigators concluded that “concurrent and staged procedures are equally safe. It is therefore reasonable to allow operator preference and patient factors to determine surgical logistics.”

Neck dissection timing has been controversial since the advent of TORS several years ago, when surgeons and administrators realized they could fit more cases into the schedule by doing neck dissections, which can take a few hours, at a different time.

Proponents of the staged approach argue, among other things, that it reduces the risk of fistulas and tracheotomies, and allows surgeons a second go at positive margins. Advocates of concurrent procedures counter that fistulas, if found, can be repaired right away, and that same-time surgery saves money, allows for earlier adjuvant therapy, and cuts anesthesia risks.

There hasn’t been much data to settle the debate, and no one has compared LOS before, so it was “important” to look into the matter, lead investigator Catherine Frenkel, MD, a Stony Brook general surgery resident, said at the American Head and Neck Society International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer.

German investigators also recently concluded that it’s pretty much a draw between concurrent and staged dissections. In a study of 41 TORS cases, “the timing of neck dissection did not make a significant difference in the outcomes. We suggest, therefore, that aspiring and established TORS teams do not restrict their appropriate indications due to robotic slot and theatre time constraints, but perform each indicated TORS case as soon as possible within their given systems, even if the neck dissections cannot be done on the same day,” they said (Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 Jun;41[6]:773-8).

In addition to obese patients, those who had tongue or tonsil lesions were more likely to be staged in the Stony Brook analysis. About half of the surgeons in the study stuck solely to concurrent procedures, while a handful opted for the staged approach, and the rest did both. Perhaps not surprisingly, high-volume surgeons – those who did five or more TORS cases per year – were more likely to stage.

Almost two-thirds of patients had at least one complication, most commonly renal failure, heart problems, extended ventilation, and surgical errors, which included accidental punctures, postop fistulas, hemorrhages, and wound complications. A total of 13% of patients had at least one postop readmission. Apart from arrhythmias, there were no statistically significant differences in complication or 30-day readmission rates between concurrent and staged patients. High-volume surgeons were less likely to have complications.

Postop bleeding was another common problem, and more likely with staged surgeries (12% vs. 7%). Concurrent procedures had a slightly higher rate of new tracheotomies and gastrostomies, but again the differences were not statistically significant, even with pedicle and free-flap reconstruction. There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Oncologic transoral robotic surgery patients spend less time in the hospital if they have neck dissections at the same time, instead of later, according to a review of 441 patients by Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The average hospital length of stay (LOS) was 6 days for the 349 patients (79.1%) who had lymphadenectomy neck dissections at the same time as transoral robotic surgery (TORS). The 92 patients (20.9%) who had staged procedures - neck dissections and TORS about a month apart, with TORS usually done first - stayed in the hospital an average of 8 days (P less than .0001). After risk adjustment, LOS was 43% shorter for concurrent dissections.

Cardiac arrhythmias were also more common in staged patients, perhaps because they had general anesthesia twice in a short period or maybe because staged patients were more likely to be obese (18.5% vs. 7.5%; P less than .01).

However, there were no statistically significant outcome differences otherwise, and the investigators concluded that “concurrent and staged procedures are equally safe. It is therefore reasonable to allow operator preference and patient factors to determine surgical logistics.”

Neck dissection timing has been controversial since the advent of TORS several years ago, when surgeons and administrators realized they could fit more cases into the schedule by doing neck dissections, which can take a few hours, at a different time.

Proponents of the staged approach argue, among other things, that it reduces the risk of fistulas and tracheotomies, and allows surgeons a second go at positive margins. Advocates of concurrent procedures counter that fistulas, if found, can be repaired right away, and that same-time surgery saves money, allows for earlier adjuvant therapy, and cuts anesthesia risks.

There hasn’t been much data to settle the debate, and no one has compared LOS before, so it was “important” to look into the matter, lead investigator Catherine Frenkel, MD, a Stony Brook general surgery resident, said at the American Head and Neck Society International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer.

German investigators also recently concluded that it’s pretty much a draw between concurrent and staged dissections. In a study of 41 TORS cases, “the timing of neck dissection did not make a significant difference in the outcomes. We suggest, therefore, that aspiring and established TORS teams do not restrict their appropriate indications due to robotic slot and theatre time constraints, but perform each indicated TORS case as soon as possible within their given systems, even if the neck dissections cannot be done on the same day,” they said (Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 Jun;41[6]:773-8).

In addition to obese patients, those who had tongue or tonsil lesions were more likely to be staged in the Stony Brook analysis. About half of the surgeons in the study stuck solely to concurrent procedures, while a handful opted for the staged approach, and the rest did both. Perhaps not surprisingly, high-volume surgeons – those who did five or more TORS cases per year – were more likely to stage.

Almost two-thirds of patients had at least one complication, most commonly renal failure, heart problems, extended ventilation, and surgical errors, which included accidental punctures, postop fistulas, hemorrhages, and wound complications. A total of 13% of patients had at least one postop readmission. Apart from arrhythmias, there were no statistically significant differences in complication or 30-day readmission rates between concurrent and staged patients. High-volume surgeons were less likely to have complications.

Postop bleeding was another common problem, and more likely with staged surgeries (12% vs. 7%). Concurrent procedures had a slightly higher rate of new tracheotomies and gastrostomies, but again the differences were not statistically significant, even with pedicle and free-flap reconstruction. There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON HEAD AND NECK CANCER

Key clinical point: Oncologic transoral robotic surgery patients spend less time in the hospital if they have neck dissections at the same time, instead of later.

Major finding: The average hospital length of stay was 6 days for the 349 patients (79.1%) who had lymphadenectomy neck dissections at the same time as TORS. The 92 patients (20.9%) who had staged procedures – neck dissections and TORS about a month apart, with TORS usually done first – stayed in the hospital an average of 8 days (P less than .0001).

Data source: Review of 441 TORS patients.

Disclosures: There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Gyn. oncologists are in demand for robotic hysterectomy

SAN DIEGO – The demand for gynecologic oncologists to perform robotic hysterectomies – even for benign indications – has increased to the point that additional fellowship training spots will be necessary to meet the need, Dr. Kayla M. Wishall said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

More and more patients want their hysterectomies performed robotically. They find the high-quality optics and minimally invasive nature of the robotic procedure appealing – smaller incisions, less blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery. And gynecologic oncologists are getting an increasing number of referrals because of their special expertise in robotic surgery and extensive experience with higher-risk patients, explained Dr. Wishall, a gynecologic oncologist at Hahnemann University Hospital/Drexel University in Philadelphia.

“This trend will likely tax the limited resources of gynecologic oncologists,” she added.

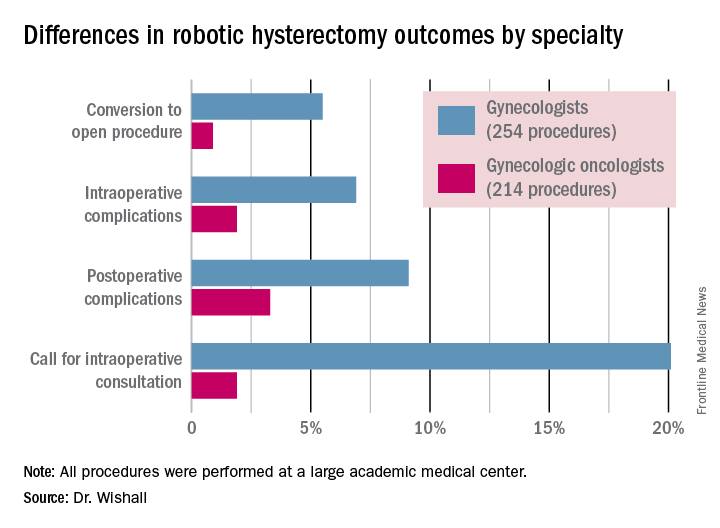

Another possible reason for the growing demand for gynecologic oncologist–performed robotic hysterectomies is that these subspecialists achieve better outcomes than gynecologists who do robotic hysterectomies, at least according to the findings of a retrospective study performed by Dr. Wishall, which included all of the 468 robotic hysterectomies performed at a large academic medical center in a recent 5-year period.

Gynecologic oncologists performed 64 (16.5%) of the 387 robotic hysterectomies done for benign indications. All told, gynecologists did 254 of the robotic hysterectomies; gynecologic oncologists performed 214.

Even though patients referred to gynecologic oncologists for these procedures were older, heavier, more likely to have had previous abdominal surgery, more often members of racial minorities, and had a higher prevalence of cardiac comorbidities, they experienced significantly fewer intra- and postoperative complications than patients whose robotic hysterectomies were performed by gynecologists, Dr. Wishall reported.

The combined intraoperative and postoperative complication rate for robotic hysterectomies performed by gynecologic oncologists was 5.2%, compared with 16% for gynecologists. But the rate of cardiac comorbidities, for instance, was 36.4% among patients seeing gynecologic oncologists, compared with 23.6% among those seeing gynecologists.

Moreover, gynecologists were about 10-fold more likely than gynecologic oncologists to call for an intraoperative consultation and sixfold more likely to convert their robotic hysterectomy to an open procedure. Their average operating room time was about 40% longer (244 minutes versus 171 minutes), too, in this single-center experience.

Dr. Wishall reported having no financial conflicts related to her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

I read this article initially with amusement and then with outrage and disdain. This article summarizes the single-site, retrospective study by Dr. Kayla Wishall at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Not only is this nonscience, but nonsensical science. As a single center retrospective study, conclusions must be suspect.

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

The comparison numbers of the two groups are small. While confounders would appear to be greater in the oncology group, we know nothing about the difficulty of the surgeries themselves – size of uterus, adnexal disease, endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, etc. Oftentimes, gynecologic oncologists dealing with endometrial carcinoma are going to face a less difficult challenge than a generalist dealing with an 18-weeks–size uterus in a woman who has undergone three prior C-sections, an open myomectomy, or stage IV endometriosis.

We are also not privy to the experience of the surgeons involved; that is, the number of procedures performed by each surgeon in the compared groups. It is certainly well known that complications decrease with surgeon experience. In a multicenter analysis by Peter Lim et al., looking at robotic assisted hysterectomies performed by high-volume surgeons (60 or more prior procedures), the intraoperative complication rate was only 0.7% and the postoperative complication rate 6.3% (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Jun;133[3]:359-64).

As a benign gynecologist who has been performing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery for 30 years and more recently, robotic surgery, I am shocked with the tenor of this study, as it would imply that unless someone is boarded in gynecologic oncology, he or she should not be performing robotic hysterectomies.

I would advise Dr. Wishall to reevaluate her surgeon population and look at the impact of experience as well as procedure difficultly. I am absolutely sure that she will find that many of the surgeons with excellent outcomes will be generalists, who are well experienced in robotic hysterectomy.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

I read this article initially with amusement and then with outrage and disdain. This article summarizes the single-site, retrospective study by Dr. Kayla Wishall at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Not only is this nonscience, but nonsensical science. As a single center retrospective study, conclusions must be suspect.

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

The comparison numbers of the two groups are small. While confounders would appear to be greater in the oncology group, we know nothing about the difficulty of the surgeries themselves – size of uterus, adnexal disease, endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, etc. Oftentimes, gynecologic oncologists dealing with endometrial carcinoma are going to face a less difficult challenge than a generalist dealing with an 18-weeks–size uterus in a woman who has undergone three prior C-sections, an open myomectomy, or stage IV endometriosis.

We are also not privy to the experience of the surgeons involved; that is, the number of procedures performed by each surgeon in the compared groups. It is certainly well known that complications decrease with surgeon experience. In a multicenter analysis by Peter Lim et al., looking at robotic assisted hysterectomies performed by high-volume surgeons (60 or more prior procedures), the intraoperative complication rate was only 0.7% and the postoperative complication rate 6.3% (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Jun;133[3]:359-64).

As a benign gynecologist who has been performing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery for 30 years and more recently, robotic surgery, I am shocked with the tenor of this study, as it would imply that unless someone is boarded in gynecologic oncology, he or she should not be performing robotic hysterectomies.

I would advise Dr. Wishall to reevaluate her surgeon population and look at the impact of experience as well as procedure difficultly. I am absolutely sure that she will find that many of the surgeons with excellent outcomes will be generalists, who are well experienced in robotic hysterectomy.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

I read this article initially with amusement and then with outrage and disdain. This article summarizes the single-site, retrospective study by Dr. Kayla Wishall at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Not only is this nonscience, but nonsensical science. As a single center retrospective study, conclusions must be suspect.

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

The comparison numbers of the two groups are small. While confounders would appear to be greater in the oncology group, we know nothing about the difficulty of the surgeries themselves – size of uterus, adnexal disease, endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, etc. Oftentimes, gynecologic oncologists dealing with endometrial carcinoma are going to face a less difficult challenge than a generalist dealing with an 18-weeks–size uterus in a woman who has undergone three prior C-sections, an open myomectomy, or stage IV endometriosis.

We are also not privy to the experience of the surgeons involved; that is, the number of procedures performed by each surgeon in the compared groups. It is certainly well known that complications decrease with surgeon experience. In a multicenter analysis by Peter Lim et al., looking at robotic assisted hysterectomies performed by high-volume surgeons (60 or more prior procedures), the intraoperative complication rate was only 0.7% and the postoperative complication rate 6.3% (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Jun;133[3]:359-64).

As a benign gynecologist who has been performing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery for 30 years and more recently, robotic surgery, I am shocked with the tenor of this study, as it would imply that unless someone is boarded in gynecologic oncology, he or she should not be performing robotic hysterectomies.

I would advise Dr. Wishall to reevaluate her surgeon population and look at the impact of experience as well as procedure difficultly. I am absolutely sure that she will find that many of the surgeons with excellent outcomes will be generalists, who are well experienced in robotic hysterectomy.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

SAN DIEGO – The demand for gynecologic oncologists to perform robotic hysterectomies – even for benign indications – has increased to the point that additional fellowship training spots will be necessary to meet the need, Dr. Kayla M. Wishall said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

More and more patients want their hysterectomies performed robotically. They find the high-quality optics and minimally invasive nature of the robotic procedure appealing – smaller incisions, less blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery. And gynecologic oncologists are getting an increasing number of referrals because of their special expertise in robotic surgery and extensive experience with higher-risk patients, explained Dr. Wishall, a gynecologic oncologist at Hahnemann University Hospital/Drexel University in Philadelphia.

“This trend will likely tax the limited resources of gynecologic oncologists,” she added.

Another possible reason for the growing demand for gynecologic oncologist–performed robotic hysterectomies is that these subspecialists achieve better outcomes than gynecologists who do robotic hysterectomies, at least according to the findings of a retrospective study performed by Dr. Wishall, which included all of the 468 robotic hysterectomies performed at a large academic medical center in a recent 5-year period.

Gynecologic oncologists performed 64 (16.5%) of the 387 robotic hysterectomies done for benign indications. All told, gynecologists did 254 of the robotic hysterectomies; gynecologic oncologists performed 214.

Even though patients referred to gynecologic oncologists for these procedures were older, heavier, more likely to have had previous abdominal surgery, more often members of racial minorities, and had a higher prevalence of cardiac comorbidities, they experienced significantly fewer intra- and postoperative complications than patients whose robotic hysterectomies were performed by gynecologists, Dr. Wishall reported.

The combined intraoperative and postoperative complication rate for robotic hysterectomies performed by gynecologic oncologists was 5.2%, compared with 16% for gynecologists. But the rate of cardiac comorbidities, for instance, was 36.4% among patients seeing gynecologic oncologists, compared with 23.6% among those seeing gynecologists.

Moreover, gynecologists were about 10-fold more likely than gynecologic oncologists to call for an intraoperative consultation and sixfold more likely to convert their robotic hysterectomy to an open procedure. Their average operating room time was about 40% longer (244 minutes versus 171 minutes), too, in this single-center experience.

Dr. Wishall reported having no financial conflicts related to her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – The demand for gynecologic oncologists to perform robotic hysterectomies – even for benign indications – has increased to the point that additional fellowship training spots will be necessary to meet the need, Dr. Kayla M. Wishall said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

More and more patients want their hysterectomies performed robotically. They find the high-quality optics and minimally invasive nature of the robotic procedure appealing – smaller incisions, less blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery. And gynecologic oncologists are getting an increasing number of referrals because of their special expertise in robotic surgery and extensive experience with higher-risk patients, explained Dr. Wishall, a gynecologic oncologist at Hahnemann University Hospital/Drexel University in Philadelphia.

“This trend will likely tax the limited resources of gynecologic oncologists,” she added.

Another possible reason for the growing demand for gynecologic oncologist–performed robotic hysterectomies is that these subspecialists achieve better outcomes than gynecologists who do robotic hysterectomies, at least according to the findings of a retrospective study performed by Dr. Wishall, which included all of the 468 robotic hysterectomies performed at a large academic medical center in a recent 5-year period.

Gynecologic oncologists performed 64 (16.5%) of the 387 robotic hysterectomies done for benign indications. All told, gynecologists did 254 of the robotic hysterectomies; gynecologic oncologists performed 214.

Even though patients referred to gynecologic oncologists for these procedures were older, heavier, more likely to have had previous abdominal surgery, more often members of racial minorities, and had a higher prevalence of cardiac comorbidities, they experienced significantly fewer intra- and postoperative complications than patients whose robotic hysterectomies were performed by gynecologists, Dr. Wishall reported.

The combined intraoperative and postoperative complication rate for robotic hysterectomies performed by gynecologic oncologists was 5.2%, compared with 16% for gynecologists. But the rate of cardiac comorbidities, for instance, was 36.4% among patients seeing gynecologic oncologists, compared with 23.6% among those seeing gynecologists.

Moreover, gynecologists were about 10-fold more likely than gynecologic oncologists to call for an intraoperative consultation and sixfold more likely to convert their robotic hysterectomy to an open procedure. Their average operating room time was about 40% longer (244 minutes versus 171 minutes), too, in this single-center experience.

Dr. Wishall reported having no financial conflicts related to her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: Gynecologic oncologists achieved better robotic hysterectomy outcomes than gynecologists despite challenging referrals.

Major finding: The combined intraoperative and postoperative complication rate for robotic hysterectomies performed by gynecologic oncologists was 5.2%, compared with 16% for gynecologists.

Data source: A retrospective observational study conducted at a single center included 254 women whose robotic hysterectomies were performed by gynecologists and 214 done by gynecologic oncologists.

Disclosures: Dr. Wishall reported having no financial conflicts related to the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.