User login

Avoid hysterectomy in POP repairs

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

Lightweight mesh reduces erosion risk after sacrocolpopexy

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

AT SGS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The odds ratio for ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) exposure, versus heavier polypropylene mesh, was not statistically significant (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 0.33-14.57).

Data source: A single-center study matching 133 erosion cases to 261 controls.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding of the study, and the investigators reported no financial disclosures.

Confirmatory blood typing unnecessary for closed prolapse repairs

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 women with closed apical prolapse repairs.

Data source: A review of more than 600 cases of apical prolapse surgery at a single center.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Long-term durability low for nonmesh vaginal prolapse repair

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall 5-year success rate was 39% in women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension and 30% in women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation.

Data source: The first randomized trial to compare the two commonly used techniques was conducted among 218 women at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network.

Disclosures: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The lead investigator reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Which treatments for pelvic floor disorders are backed by evidence?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

2016 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction

The genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a constellation of symptoms and signs of a hypoestrogenic state resulting in some or all of the following: vaginal dryness, burning, irritation, dyspareunia, urinary urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections.1 In 2014, the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society endorsed “GSM” as a new term to replace the less comprehensive description, vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA).1

The prevalence of GSM is around 50%, but it may increase each year after menopause, reaching up to 84.2%.2,3 Only about half of women affected seek medical care, with the most commonly reported symptoms being vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.3,4

Nonhormonal vaginal moisturizers andlubricants remain first-line treatment. The benefits are temporary and short lived because these options do not change the physiologic makeup of the vaginal wall; these treatments therefore provide relief only if the GSM symptoms are limited or mild.5

In this Update on pelvic floor dysfunction, we review 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of hormonal options (vaginal estrogen and oral ospemifene) and examine the latest information regarding fractional CO2 vaginal laser treatment. Also included are evidence-based guidelines for vaginal estrogen use and recommendations and conclusions for use of vaginal estrogen in women with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer. (The terms used in the studies described [ie, VVA versus GSM] have been maintained for accuracy of reporting.)

Low-dose estrogen vaginal cream ameliorates moderate to severe VVA with limited adverse events

Freedman M, Kaunitz AM, Reape KZ, Hait H, Shu H. Twice-weekly synthetic conjugated estrogens vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2009;16(4):735-741.

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, Freedman and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of a 1-g dose of synthetic conjugated estrogens A (SCE-A) cream versus placebo in postmenopausal women with moderate to severe VVA.

Details of the study

The investigators enrolled 305 participants aged 30 to 80 years (mean [SD] age, 60 [6.6] years) who were naturally or surgically postmenopausal. The enrollment criteria included ≤5% superficial cells on vaginal smear, vaginal pH >5.0, and at least 1 moderate or severe symptom of VVA (vaginal dryness, soreness, irritation/itching, pain with intercourse, or bleeding after intercourse).

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to twice-weekly therapy with 1 g (0.625 mg/g) SCE-A vaginal cream, 2 g SCE-A vaginal cream, 1 g placebo, or 2 g placebo. Study visits occurred on days 14, 21, 28, 56, and 84 (12-week end point). The 3 co-primary outcomes were cytology, vaginal pH, and most bothersome symptom (MBS). Primary outcomes and safety/adverse events (AEs) were recorded at each study visit, and transvaginal ultrasound and endometrial biopsy were performed for women with a uterus at the beginning and end of the study.

Mean change and percent change in the 3 primary outcomes were assessed between baseline and each study visit. MBS was scored on a scale of 0 to 3 (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). The principal indicators of efficacy were the changes from baseline to the end of treatment (12 weeks) for each of the 3 end points. Since the 1-g and 2-g SCE-A dose groups showed a similar degree of efficacy on all 3 co-primary end points, approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was sought only for the lower dose, in keeping with the use of the lowest effective dose; therefore, results from only the 1-g SCE-A dose group and matching placebo group were presented in the article. A sample size calculation determined that at least 111 participants in each group were needed to provide 90% power for statistical testing.

Estrogen reduced MBS severity, improved vaginal indices

The modified intent-to-treat (MITT) cohort was used for outcome analysis, and data from 275 participants were available at the 12-week end point. At baseline, 132 participants (48%) indicated vaginal dryness and 86 women (31.3%) indicated pain during intercourse as the MBS. In the SCE-A group at baseline, the vaginal maturation index (VMI) was 31.31 compared with 31.84 in the placebo group. At 12 weeks, the SCE-A group had a mean reduction of 1.71 in overall MBS severity compared with the placebo group’s mean reduction of 1.11 (P<.0001). The SCE-A group had a greater increase in the VMI (with a mean change of 31.46 vs 5.16 in the placebo group [P<.0001]) and a greater decrease in the vaginal pH (mean pH at the end of treatment for the SCE-A group was 4.84, a decrease of 1.48, and for the placebo group was 5.96, a decrease of 0.31 [P<.0001]).

Adverse events. The incidence of AEs was similar for the 1-g SCE-A group and the 1-g placebo group, with no AE occurring at a rate of higher than 5%. There were 15 (10%) treatment-related AEs in the estrogen group and 16 (10.3%) in the placebo group. The SCE-A group had 3 AEs (2%) leading to discontinuation, while the placebo group had 2 AEs (1.3%) leading to discontinuation. There were no clinically significant endometrial biopsy findings at the conclusion of the study.

Strengths and limitations. This study evaluated clinical and physiologic outcomes as well as uterine response to transvaginal estrogen. The use of MBS allows symptoms to be scored objectively compared with prior subjective symptom assessment, which varied widely. However, fewer indicated symptoms will permit limited conclusions.

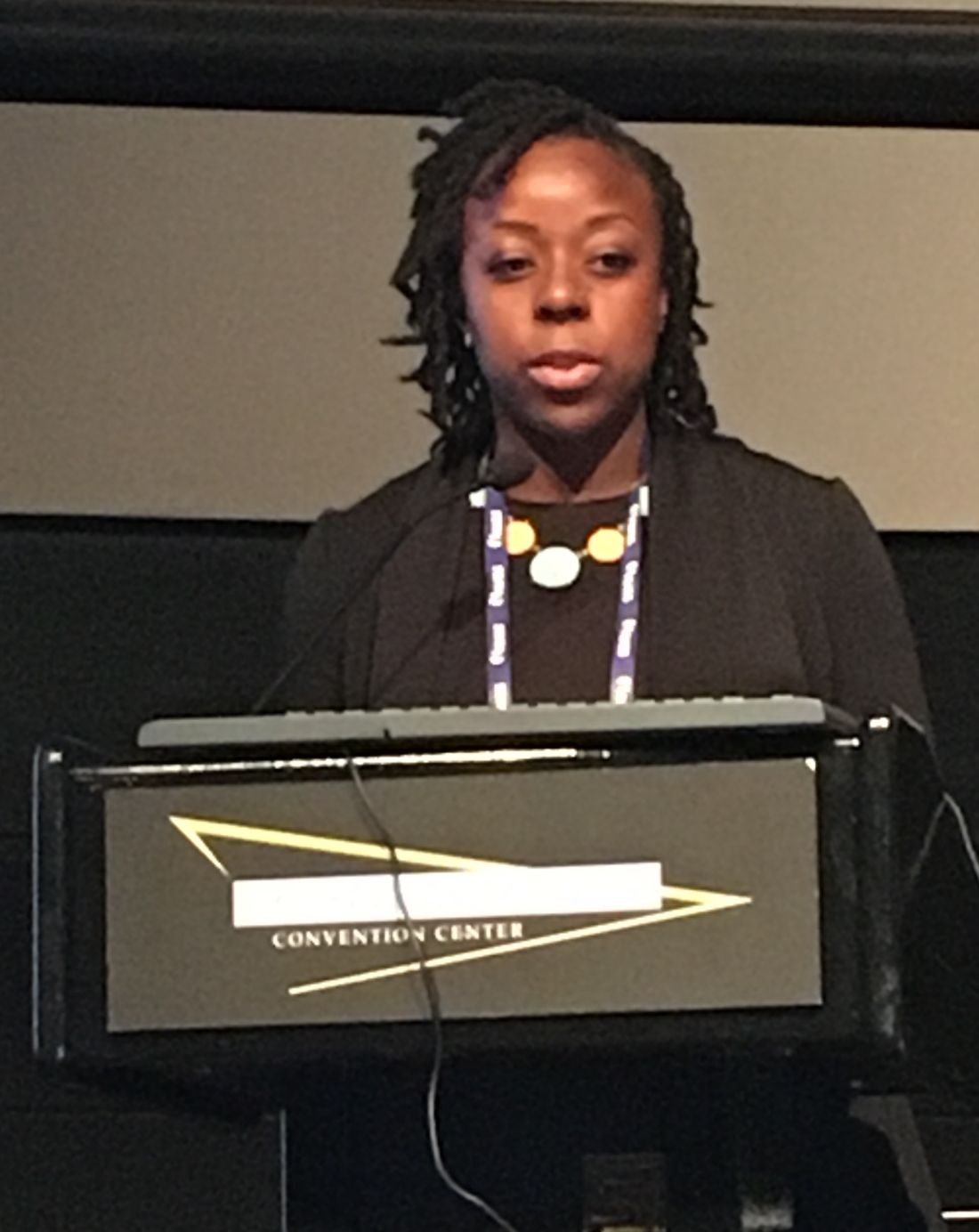

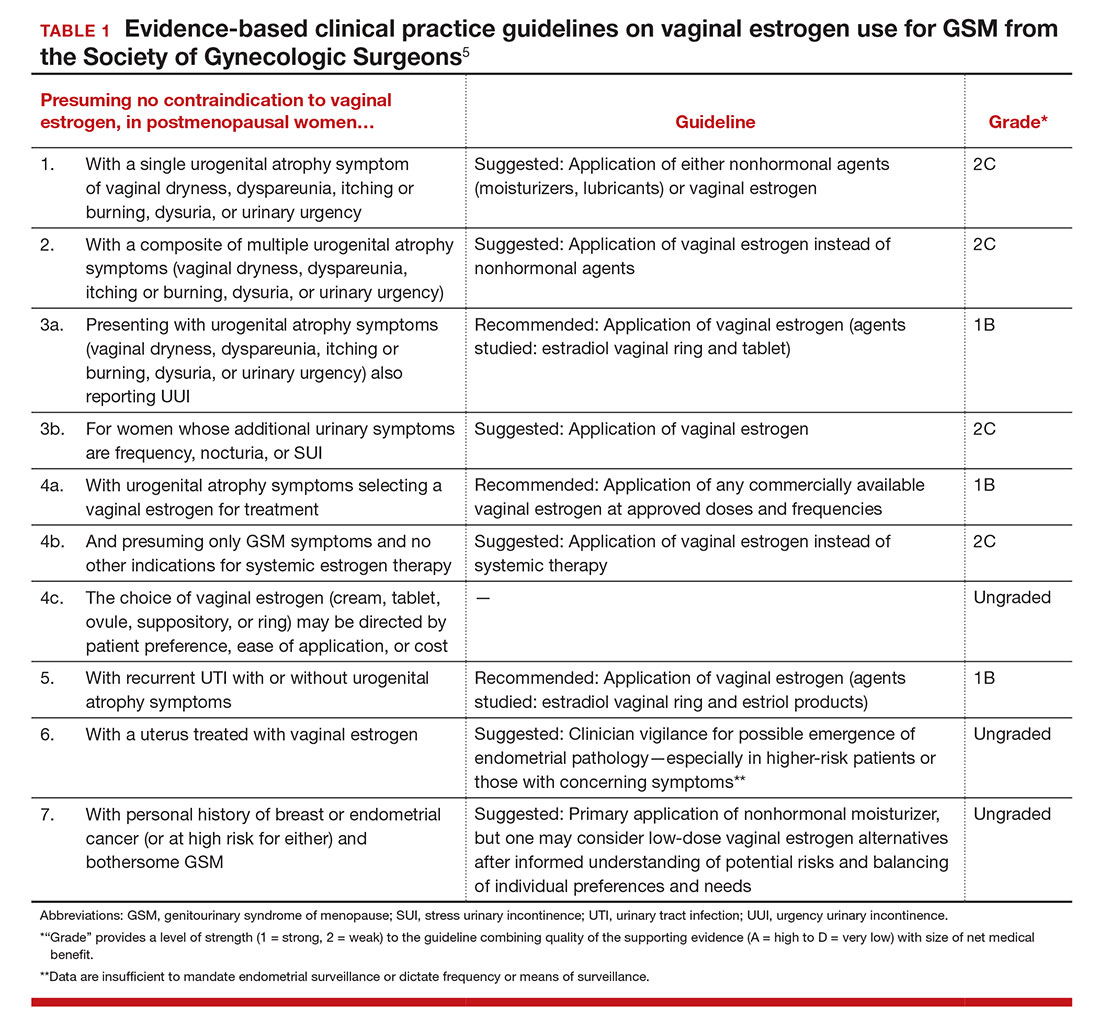

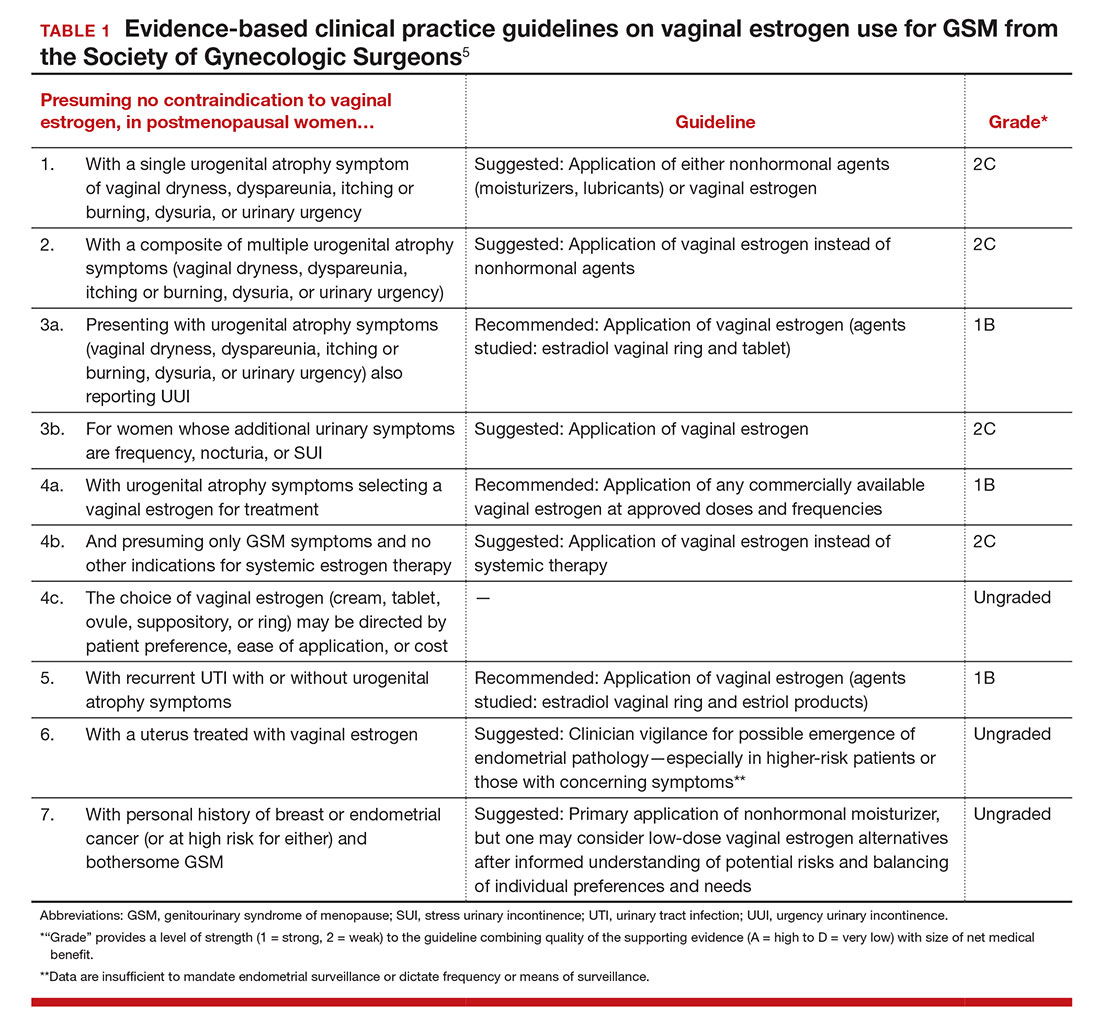

For evidence-based recommended and suggested treatments for various genitourinary symptoms, we recommended as a resource the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons clinical practice guidelines on vaginal estrogen for the treatment of GSM (TABLE 1).5

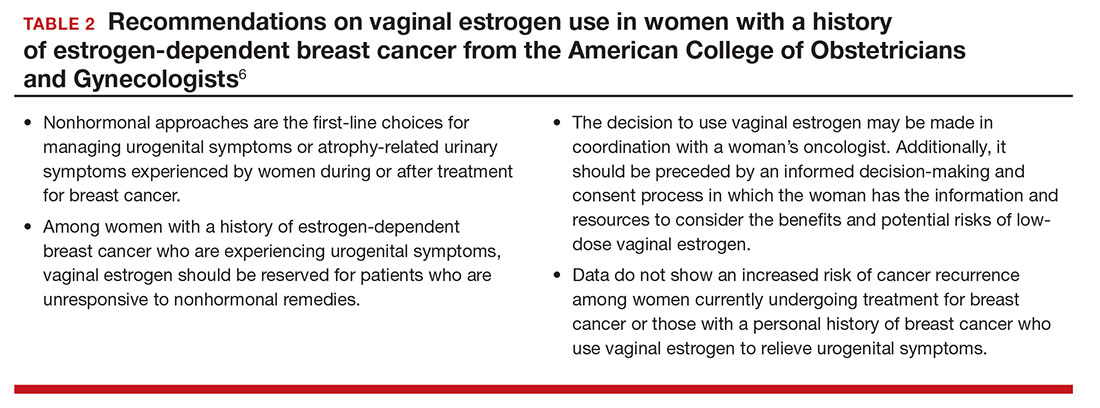

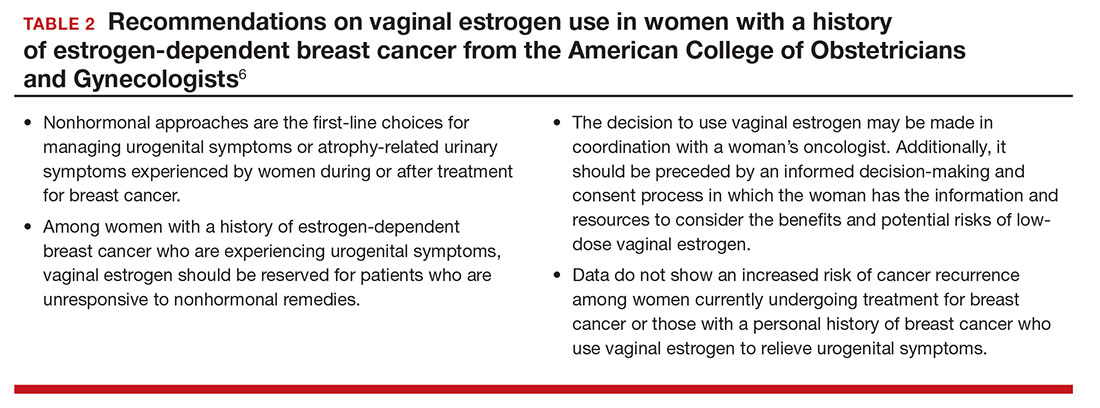

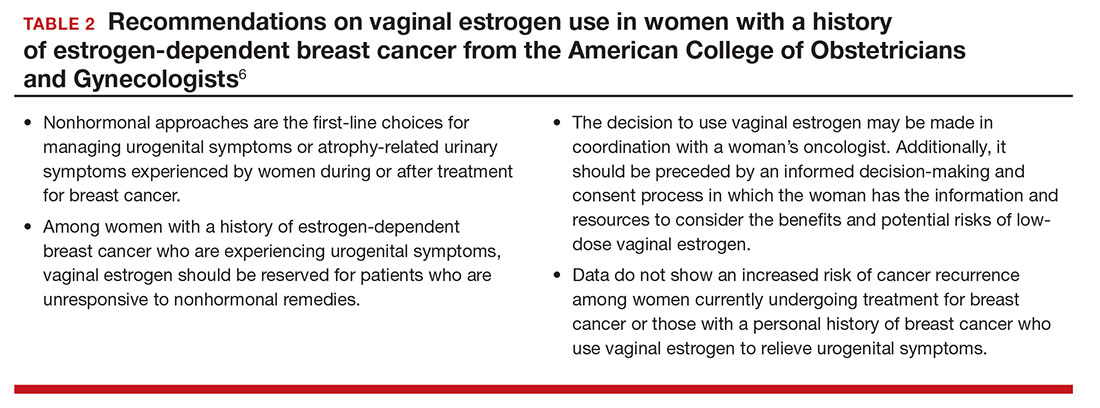

In addition, for women with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer experiencing urogenital symptoms, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends nonhormonal agents as first-line therapy, with vaginal estrogen treatment reserved for woman whose symptoms are unresponsive to nonhormonal therapies (TABLE 2).6

Ospemifene improves vaginal physiology and dyspareunia

Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

Bachmann and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of ospemifene for the treatment of VVA. This is one of the efficacy studies on which FDA approval was based. Ospemifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that acts as an estrogen agonist/antagonist.

Details of the study

The study included 826 postmenopausal women randomly assigned to 30 mg/day of ospemifene, 60 mg/day of ospemifene, or placebo for 12 weeks. Participants were aged 40 to 80 years and met the criteria for VVA (defined as ≤5% superficial cells on vaginal smear [maturation index], vaginal pH >5.0, and at least 1 moderate or severe symptom of VVA). All women were given a nonhormonal lubricant for use as needed.

There were 4 co-primary end points: percentage of superficial cells on the vaginal smear, percentage of parabasal cells on the vaginal smear, vaginal pH, and self-assessed MBS using a Likert scale (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe). The symptom score was calculated as the change from baseline to week 12 for each MBS. Safety was assessed by patient report; if a participant had an intact uterus and cervix, Pap test, endometrial thickness, and endometrial histologic analysis were performed at baseline and at 12 weeks. Baseline characteristics were similar among all treatment groups. A total of 46% of participants reported dyspareunia as their MBS, and 39% reported vaginal dryness.

Two dose levels of ospemifene effectively relieve symptoms

After 12 weeks of treatment, both the 30-mg and the 60-mg dose of ospemifene produced a statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness and objective results of maturation index and vaginal pH compared with placebo. Vaginal dryness decreased in the ospemifene 30-mg group (1.22) and in the ospemifene 60-mg group (1.26) compared with placebo (0.84) (P = .04 for the 30-mg group and P = .021 for the 60-mg group). The percentage of superficial cells was increased in both treatment groups compared with placebo (7.8% for the 30-mg group, 10.8% for the 60-mg group, 2.2% for the placebo group; P<.001 for both). The percentage of parabasal cells decreased in both treatment groups compared with participants who received placebo (21.9% in the 30-mg group, 30.1% in the 60-mg group, and 3.98% in the placebo group; P<.001 for both). Both treatment groups had a decrease in vaginal pH versus the placebo group as well (0.67 decrease in the 30-mg group, 1.01 decrease in the 60-mg group, and 0.10 decrease in the placebo group; P<.001 for both). The 60-mg/day ospemifene dose improved dyspareunia compared with placebo and was more effective than the 30-mg dose for all end points.

Adverse effects. Hot flashes were reported in 9.6% of the 30-mg ospemifene group and in 8.3% of the 60-mg group, compared with 3.4% in the placebo group. The increased percentage of participants with hot flashes in the ospemifene groups did not lead to increased discontinuation with the study. Urinary tract infections, defined by symptoms only, were more common in the ospemifene groups (4.6% in the 30-mg group, 7.2% in the 60-mg group, and 2.2% in the placebo group). In each group, 5% of patients discontinued the study because of AEs. There were 5 serious AEs in the 30-mg ospemifene group, 4 serious AEs in the placebo group, and none in the 60-mg group. No venous thromboembolic events were reported.

Strengths and limitations. Vaginal physiology as well as common symptoms of GSM were assessed in this large study. However, AEs were self-reported. While ospemifene was found safe and well tolerated when the study was extended for an additional 52 weeks (in women without a uterus) and 40 weeks (in women with a uterus), longer follow-up is needed to determine endometrial safety.7,8

Some patients may prefer an oral agent over a vaginally applied medication. While ospemifene is not an estrogen, it is a SERM that may increase the risk of endometrial cancer and thromboembolic events as stated in the boxed warning of the ospemifene prescribing information.

Fractional CO2 laser for VVA shows efficacy, patient satisfaction

Sokol ER, Karram MM. An assessment of the safety and efficacy of a fractional CO2 laser system for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2016;23(10):1102–1107.

In this first US pilot study, postmenopausal women received 3 fractional CO2 laser treatments, 6 weeks apart. The investigators evaluated the safety and efficacy of the treatment for GSM.

Details of the study

Thirty women (mean age, 58.6 years) who were nonsmokers, postmenopausal, had less than stage 2 prolapse, no vaginal procedures for the past 6 months, and did not use vaginal creams, moisturizers, lubricants, or homeopathic preparations for the past 3 months were enrolled. Participants received 3 laser treatments with the SmartXide2, MonaLisa Touch (DEKA M.E.L.A. SRL, Florence, Italy) device at 6-week intervals followed by a 3-month follow-up.

The primary outcome was visual analog scale (VAS) change in 6 categories (vaginal pain, burning, itching, dryness, dyspareunia, and dysuria) assessed from baseline to after each treatment, including 3 months after the final treatment, using an 11-point scale with 0 the lowest (no symptoms) and 10 the highest (extreme bother). Secondary outcomes were Vaginal Health Index (VHI) score, maximal tolerable dilator size, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire score, general quality of life, degree of difficulty performing the procedure, participant satisfaction, vaginal pH, adverse effects, and treatment discomfort assessed using the VAS.

Improved VVA symptoms and vaginal caliber

Twenty-seven women completed the study. There was a statistically significant change in all 6 symptom categories measured with the VAS. Improvement change (SD) on the VAS was 1.7 (3.2) for pain, 1.4 (2.9) for burning, 1.4 (1.9) for itching, 1.0 (2.4) for dysuria, comparing baseline scores to scores after 3 treatments (all with P<.05). A greater improvement was noted for dryness, 6.1 (2.7), and for dyspareunia, 5.4 (2.9) (both P<.001). There was also a statistically significant change in overall improvement on the VHI and the FSFI. The mean (SD) VHI score at baseline was 14.4 (2.9; range, 8 to 20) and the mean (SD) after 3 laser treatments was 21.4 (2.9; range, 16 to 25), with an overall mean (SD) improvement of 7.0 (3.1; P<.001).

Twenty-six participants completed a follow-up FSFI, with a mean (SD) baseline score of 11.3 (7.3; range, 2 to 25) and a follow-up mean (SD) score of 8.8 (7.3; range, −3.7 to 27.2) (P<.001). There was an increase in dilator size of 83% when comparing baseline to follow-up. At baseline, 24 participants (80%) could comfortably accept an XS or S dilator, and at follow-up 23 of 24 women (96%) could comfortably accept an M or L dilator.

Adverse effects. At their follow-up, 96% of participants were satisfied or extremely satisfied with treatment. Two women reported mild-to-moderate pain lasting 2 to 3 days, and 2 had minor bleeding; however, no women withdrew or discontinued treatment because of adverse events.

Study limitations. This study evaluated the majority of GSM symptoms as well as change in vaginal caliber after a nonhormonal therapy. The cohort was small and had no placebo group. In addition, with the limited observation period, it is difficult to determine the duration of effect and long-term safety of repeated treatments.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML: Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2014;79(3):349–354.

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437–447.

- Palma F, Volpe A, Villa P, Cagnacci A; Writing Groupt of AGATA Study. Vaginal atrophy of women in postmenopause. Results from a multicentric observational study: the AGATA study. Maturitas. 2016;83:40–44.