User login

Immunotherapy may benefit relapsed HSCT recipients

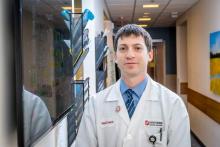

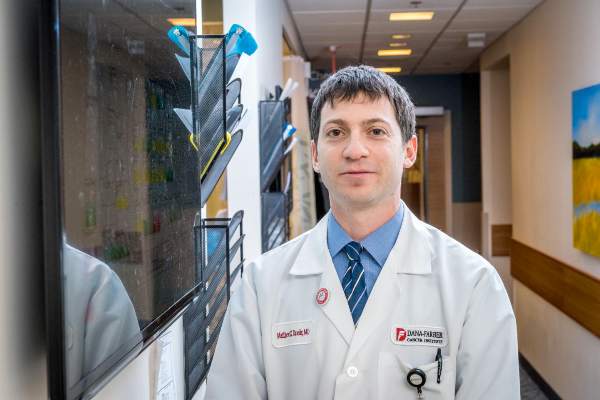

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Ipilimumab may restore antitumor immunity after relapse from HSCT

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Anti-CTLA-4 therapy may restore graft-versus-tumor effect in patients with hematologic malignancies relapsed after allogeneic transplantation.

Major finding: Five of 22 patients on a 10-mg/kg dose of ipilimumab had a complete response.

Data source: Phase I/Ib investigator-initiated study of 28 patients with hematologic malignancies relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

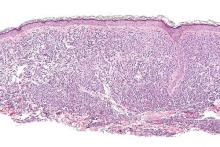

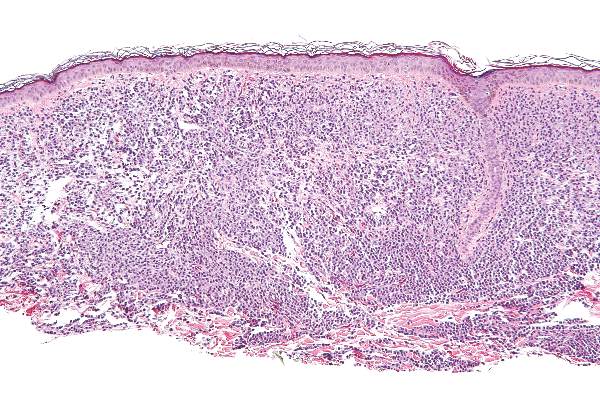

Midostaurin cut organ damage in systemic mastocytosis

Midostaurin completely resolved at least one type of organ damage for 45% of patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, based on a multicenter, open-label, phase II, industry-sponsored trial.

“Response rates were similar regardless of the subtype of advanced systemic mastocytosis, KIT mutation status, or exposure to previous therapy,” reported Jason R. Gotlib, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his associates. Adverse effects led to dose reductions for 41% of patients, however, and caused 22% of patients to stop treatment, the researchers wrote online June 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic mastocytosis is related to a constitutively activated receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the KIT D816V mutation. As neoplastic mast cells infiltrate and damage organs, patients develop cytopenias, hypoalbuminemia, osteolytic bone lesions, abnormal liver function, ascites, and weight loss. Mastocytosis lacks effective treatments, and patients with aggressive disease tend to live about 3.5 years, the researchers noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 29;374:2530-40).

Of 116 patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, 27 lacked measurable signs of disease or had unrelated signs and symptoms. The remaining 89 patients included 16 with aggressive systemic disease, 57 with systemic disease and an associated hematologic neoplasm, and 16 with mast cell leukemia. Patients received 100 mg oral midostaurin twice daily in continuous 4-week cycles for a median of 11.4 months, with a median follow-up of 26 months.

In all, 53 (60%) patients experienced at least 50% improvement in one type of organ damage or improvement in more than one type of organ damage, said the researchers. These responders included 12 patients with aggressive systemic mastocytosis, 33 patients with systemic mastocytosis and a hematologic neoplasm, and eight patients with mast-cell leukemia. No one achieved complete remission, but after six treatment cycles, 45% of patients had complete resolution of at least one type of organ damage.

Patients typically experienced, at best, a nearly 60% drop in bone marrow mast cell burden and serum tryptase. The median duration of response was 24 months, median overall survival was 28.7 months, and median progression-free survival was 14.1 months. Mast cell leukemia and a history of treatment for mastocytosis were tied to shorter survival, while a 50% decrease in mast cell burden significantly improved survival (hazard ratio, 0.33; P = .01).

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic abnormalities included neutropenia (24% of patients), anemia (41%), and thrombocytopenia (29%). Marked myelosuppression was associated with baseline cytopenia and may have reflected either treatment-related effects or disease progression, the researchers said. The most common grade 3/4 nonhematologic adverse effects were fatigue (9% of patients) and diarrhea (8%).

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study, and designed it and collected the data with the authors. Dr. Gotlib disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Ten coinvestigators disclosed financial ties to Novartis and to several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators disclosed direct research support from Novartis. The remaining four coinvestigators had no disclosures.

Midostaurin completely resolved at least one type of organ damage for 45% of patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, based on a multicenter, open-label, phase II, industry-sponsored trial.

“Response rates were similar regardless of the subtype of advanced systemic mastocytosis, KIT mutation status, or exposure to previous therapy,” reported Jason R. Gotlib, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his associates. Adverse effects led to dose reductions for 41% of patients, however, and caused 22% of patients to stop treatment, the researchers wrote online June 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic mastocytosis is related to a constitutively activated receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the KIT D816V mutation. As neoplastic mast cells infiltrate and damage organs, patients develop cytopenias, hypoalbuminemia, osteolytic bone lesions, abnormal liver function, ascites, and weight loss. Mastocytosis lacks effective treatments, and patients with aggressive disease tend to live about 3.5 years, the researchers noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 29;374:2530-40).

Of 116 patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, 27 lacked measurable signs of disease or had unrelated signs and symptoms. The remaining 89 patients included 16 with aggressive systemic disease, 57 with systemic disease and an associated hematologic neoplasm, and 16 with mast cell leukemia. Patients received 100 mg oral midostaurin twice daily in continuous 4-week cycles for a median of 11.4 months, with a median follow-up of 26 months.

In all, 53 (60%) patients experienced at least 50% improvement in one type of organ damage or improvement in more than one type of organ damage, said the researchers. These responders included 12 patients with aggressive systemic mastocytosis, 33 patients with systemic mastocytosis and a hematologic neoplasm, and eight patients with mast-cell leukemia. No one achieved complete remission, but after six treatment cycles, 45% of patients had complete resolution of at least one type of organ damage.

Patients typically experienced, at best, a nearly 60% drop in bone marrow mast cell burden and serum tryptase. The median duration of response was 24 months, median overall survival was 28.7 months, and median progression-free survival was 14.1 months. Mast cell leukemia and a history of treatment for mastocytosis were tied to shorter survival, while a 50% decrease in mast cell burden significantly improved survival (hazard ratio, 0.33; P = .01).

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic abnormalities included neutropenia (24% of patients), anemia (41%), and thrombocytopenia (29%). Marked myelosuppression was associated with baseline cytopenia and may have reflected either treatment-related effects or disease progression, the researchers said. The most common grade 3/4 nonhematologic adverse effects were fatigue (9% of patients) and diarrhea (8%).

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study, and designed it and collected the data with the authors. Dr. Gotlib disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Ten coinvestigators disclosed financial ties to Novartis and to several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators disclosed direct research support from Novartis. The remaining four coinvestigators had no disclosures.

Midostaurin completely resolved at least one type of organ damage for 45% of patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, based on a multicenter, open-label, phase II, industry-sponsored trial.

“Response rates were similar regardless of the subtype of advanced systemic mastocytosis, KIT mutation status, or exposure to previous therapy,” reported Jason R. Gotlib, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his associates. Adverse effects led to dose reductions for 41% of patients, however, and caused 22% of patients to stop treatment, the researchers wrote online June 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic mastocytosis is related to a constitutively activated receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the KIT D816V mutation. As neoplastic mast cells infiltrate and damage organs, patients develop cytopenias, hypoalbuminemia, osteolytic bone lesions, abnormal liver function, ascites, and weight loss. Mastocytosis lacks effective treatments, and patients with aggressive disease tend to live about 3.5 years, the researchers noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 29;374:2530-40).

Of 116 patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, 27 lacked measurable signs of disease or had unrelated signs and symptoms. The remaining 89 patients included 16 with aggressive systemic disease, 57 with systemic disease and an associated hematologic neoplasm, and 16 with mast cell leukemia. Patients received 100 mg oral midostaurin twice daily in continuous 4-week cycles for a median of 11.4 months, with a median follow-up of 26 months.

In all, 53 (60%) patients experienced at least 50% improvement in one type of organ damage or improvement in more than one type of organ damage, said the researchers. These responders included 12 patients with aggressive systemic mastocytosis, 33 patients with systemic mastocytosis and a hematologic neoplasm, and eight patients with mast-cell leukemia. No one achieved complete remission, but after six treatment cycles, 45% of patients had complete resolution of at least one type of organ damage.

Patients typically experienced, at best, a nearly 60% drop in bone marrow mast cell burden and serum tryptase. The median duration of response was 24 months, median overall survival was 28.7 months, and median progression-free survival was 14.1 months. Mast cell leukemia and a history of treatment for mastocytosis were tied to shorter survival, while a 50% decrease in mast cell burden significantly improved survival (hazard ratio, 0.33; P = .01).

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic abnormalities included neutropenia (24% of patients), anemia (41%), and thrombocytopenia (29%). Marked myelosuppression was associated with baseline cytopenia and may have reflected either treatment-related effects or disease progression, the researchers said. The most common grade 3/4 nonhematologic adverse effects were fatigue (9% of patients) and diarrhea (8%).

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study, and designed it and collected the data with the authors. Dr. Gotlib disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Ten coinvestigators disclosed financial ties to Novartis and to several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators disclosed direct research support from Novartis. The remaining four coinvestigators had no disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Midostaurin helped to resolve organ damage related to mastocytosis.

Major finding: In all, 45% of patients had complete resolution of at least one type of organ damage within six, 4-week treatment cycles.

Data source: An international, open-label, phase II study of 116 patients given 100 mg oral midostaurin twice daily.

Disclosures: Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study, designed the study, and collected the data together with the authors. Dr. Gotlib disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Ten coinvestigators disclosed financial ties to Novartis and to several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators disclosed direct research support from Novartis. Four coinvestigators had no disclosures.

Lenalidomide eliminated transfusion dependence for a minority of non-del(5q) MDS patients

Lenalidomide led to independence from red blood cell transfusions for 27% of patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who were refractory to or ineligible for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, based on the results of a phase III placebo-controlled study.

Patients were most likely to reach this primary endpoint if their baseline erythropoietin (EPO) level was less than 100 mU/mL, Dr. Valeria Santini of the University of Florence (Italy) and her associates wrote online June 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) are first-line therapy for anemia in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) patients without a deletion 5q, but most patients stop responding over time. “Although azacitidine and decitabine are approved in the United States and other countries in this setting, no approved treatments exist in the European Union and other countries for ESA-refractory patients who are dependent on red blood cell transfusions,” the researchers wrote.

Their international double-blind study enrolled 239 adults with International Prognostic Scoring System lower- or intermediate-risk MDS who lacked the del(5q) mutation and needed at least 2 U of packed red blood cells every 28 days. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to lenalidomide (160 patients) or placebo (79 patients), given once daily for 28-day cycles. Patients whose creatinine clearance was 40-60 mL/min received 5 mg lenalidomide, while the rest received 10 mg. Randomization was stratified based on MDS treatment history, baseline transfusion requirements, and time from MDS diagnosis (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0118). A total of 43 lenalidomide patients (27%) and 2 placebo patients (2.5%; P less than .001) did not require packed red blood cell transfusions for at least 8 weeks. Transfusion independence persisted through 24 weeks for 17% of lenalidomide patients and no placebo patients. Of 39 patients given 5-mg lenalidomide, 18% reached the primary endpoint (P = .006, compared with placebo). The median duration of response was nearly 31 weeks (95% confidence interval, 21-59 weeks). Prior use of ESAs was the only significant predictor of response in the multivariate analysis (odds ratio, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.1; P = .01), although low baseline transfusion burden reached significance in the univariate model and borderline significance in the multivariate model (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 0.96-7.6; P = .06).

The highest response rate (43%) occurred among the 40 patients who had previously received ESAs and had a baseline erythropoietin level under 100 mU/mL. The response rates for other patients previously treated with ESAs fell as baseline EPO level increased, and the response rate was only 9% among patients whose relatively high endogenous EPO level had made them ineligible for ESA treatment. “Patients with higher endogenous EPO levels may be less responsive due to marked intrinsic defects in erythroid signaling pathways, including signal transducer and activator of transcription extracellular regulated kinase 1/2, and lipid raft assembly, which are restored or stimulated by lenalidomide exposure,” the researchers wrote.

As in previous studies, grade 3-4 adverse events with lenalidomide usually were due to myelosuppression. Grade 3-4 neutropenia affected 99 lenalidomide patients (62%) and 10 placebo patients (13%). Grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia affected 57 lenalidomide patients (36%) and 3 placebo patients (4%). Lenalidomide was associated with a 3% rate of venous thrombosis but did not cause detectable pulmonary embolism. Lenalidomide was stopped in 32% of patients because of thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, or other adverse events, compared with 11% of placebo patients. In all, 2.5% of patients in each group died while on treatment.

Celgene makes lenalidomide and funded the study. Dr. Santini disclosed consulting or advisory roles and honoraria from Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Seventeen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Celgene.

Have goals of therapy been met in treating patients with lower-risk, non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes with lenalidomide? For patients requiring a median of 3 U of packed red blood cells monthly, approximately one-quarter will respond to the drug for a median of little more than 7 months. In exchange, nearly three-quarters of patients will take a pill unnecessarily, with most experiencing cytopenias, for a median of more than 5 months. These data were submitted to the FDA in a supplementary new drug application for an expanded indication for lenalidomide in the non-del(5q) MDS population. The submission was subsequently withdrawn, however, when further analyses and data were requested to support the risk-benefit assessment.

For the majority of these patients, then, neither quality of life nor transfusion requirements improved, and lenalidomide use in patients with non-del(5q) MDS will continue to be relegated to the off-label realm. For a tantalizing few, including at least one patient whose response lasted for 5 years, the drug is extremely effective, and it is now our responsibility, as clinical and translational scientists, to determine how we can better identify those people, and make the long day’s journey into night even longer.

Dr. Mikkael A. Sekeres is at the Cleveland Clinic. He disclosed advisory or consulting ties to Celgene, the maker of lenalidomide. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2492).

Have goals of therapy been met in treating patients with lower-risk, non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes with lenalidomide? For patients requiring a median of 3 U of packed red blood cells monthly, approximately one-quarter will respond to the drug for a median of little more than 7 months. In exchange, nearly three-quarters of patients will take a pill unnecessarily, with most experiencing cytopenias, for a median of more than 5 months. These data were submitted to the FDA in a supplementary new drug application for an expanded indication for lenalidomide in the non-del(5q) MDS population. The submission was subsequently withdrawn, however, when further analyses and data were requested to support the risk-benefit assessment.

For the majority of these patients, then, neither quality of life nor transfusion requirements improved, and lenalidomide use in patients with non-del(5q) MDS will continue to be relegated to the off-label realm. For a tantalizing few, including at least one patient whose response lasted for 5 years, the drug is extremely effective, and it is now our responsibility, as clinical and translational scientists, to determine how we can better identify those people, and make the long day’s journey into night even longer.

Dr. Mikkael A. Sekeres is at the Cleveland Clinic. He disclosed advisory or consulting ties to Celgene, the maker of lenalidomide. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2492).

Have goals of therapy been met in treating patients with lower-risk, non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes with lenalidomide? For patients requiring a median of 3 U of packed red blood cells monthly, approximately one-quarter will respond to the drug for a median of little more than 7 months. In exchange, nearly three-quarters of patients will take a pill unnecessarily, with most experiencing cytopenias, for a median of more than 5 months. These data were submitted to the FDA in a supplementary new drug application for an expanded indication for lenalidomide in the non-del(5q) MDS population. The submission was subsequently withdrawn, however, when further analyses and data were requested to support the risk-benefit assessment.

For the majority of these patients, then, neither quality of life nor transfusion requirements improved, and lenalidomide use in patients with non-del(5q) MDS will continue to be relegated to the off-label realm. For a tantalizing few, including at least one patient whose response lasted for 5 years, the drug is extremely effective, and it is now our responsibility, as clinical and translational scientists, to determine how we can better identify those people, and make the long day’s journey into night even longer.

Dr. Mikkael A. Sekeres is at the Cleveland Clinic. He disclosed advisory or consulting ties to Celgene, the maker of lenalidomide. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2492).

Lenalidomide led to independence from red blood cell transfusions for 27% of patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who were refractory to or ineligible for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, based on the results of a phase III placebo-controlled study.

Patients were most likely to reach this primary endpoint if their baseline erythropoietin (EPO) level was less than 100 mU/mL, Dr. Valeria Santini of the University of Florence (Italy) and her associates wrote online June 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) are first-line therapy for anemia in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) patients without a deletion 5q, but most patients stop responding over time. “Although azacitidine and decitabine are approved in the United States and other countries in this setting, no approved treatments exist in the European Union and other countries for ESA-refractory patients who are dependent on red blood cell transfusions,” the researchers wrote.

Their international double-blind study enrolled 239 adults with International Prognostic Scoring System lower- or intermediate-risk MDS who lacked the del(5q) mutation and needed at least 2 U of packed red blood cells every 28 days. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to lenalidomide (160 patients) or placebo (79 patients), given once daily for 28-day cycles. Patients whose creatinine clearance was 40-60 mL/min received 5 mg lenalidomide, while the rest received 10 mg. Randomization was stratified based on MDS treatment history, baseline transfusion requirements, and time from MDS diagnosis (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0118). A total of 43 lenalidomide patients (27%) and 2 placebo patients (2.5%; P less than .001) did not require packed red blood cell transfusions for at least 8 weeks. Transfusion independence persisted through 24 weeks for 17% of lenalidomide patients and no placebo patients. Of 39 patients given 5-mg lenalidomide, 18% reached the primary endpoint (P = .006, compared with placebo). The median duration of response was nearly 31 weeks (95% confidence interval, 21-59 weeks). Prior use of ESAs was the only significant predictor of response in the multivariate analysis (odds ratio, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.1; P = .01), although low baseline transfusion burden reached significance in the univariate model and borderline significance in the multivariate model (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 0.96-7.6; P = .06).

The highest response rate (43%) occurred among the 40 patients who had previously received ESAs and had a baseline erythropoietin level under 100 mU/mL. The response rates for other patients previously treated with ESAs fell as baseline EPO level increased, and the response rate was only 9% among patients whose relatively high endogenous EPO level had made them ineligible for ESA treatment. “Patients with higher endogenous EPO levels may be less responsive due to marked intrinsic defects in erythroid signaling pathways, including signal transducer and activator of transcription extracellular regulated kinase 1/2, and lipid raft assembly, which are restored or stimulated by lenalidomide exposure,” the researchers wrote.

As in previous studies, grade 3-4 adverse events with lenalidomide usually were due to myelosuppression. Grade 3-4 neutropenia affected 99 lenalidomide patients (62%) and 10 placebo patients (13%). Grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia affected 57 lenalidomide patients (36%) and 3 placebo patients (4%). Lenalidomide was associated with a 3% rate of venous thrombosis but did not cause detectable pulmonary embolism. Lenalidomide was stopped in 32% of patients because of thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, or other adverse events, compared with 11% of placebo patients. In all, 2.5% of patients in each group died while on treatment.

Celgene makes lenalidomide and funded the study. Dr. Santini disclosed consulting or advisory roles and honoraria from Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Seventeen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Celgene.

Lenalidomide led to independence from red blood cell transfusions for 27% of patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who were refractory to or ineligible for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, based on the results of a phase III placebo-controlled study.

Patients were most likely to reach this primary endpoint if their baseline erythropoietin (EPO) level was less than 100 mU/mL, Dr. Valeria Santini of the University of Florence (Italy) and her associates wrote online June 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) are first-line therapy for anemia in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) patients without a deletion 5q, but most patients stop responding over time. “Although azacitidine and decitabine are approved in the United States and other countries in this setting, no approved treatments exist in the European Union and other countries for ESA-refractory patients who are dependent on red blood cell transfusions,” the researchers wrote.

Their international double-blind study enrolled 239 adults with International Prognostic Scoring System lower- or intermediate-risk MDS who lacked the del(5q) mutation and needed at least 2 U of packed red blood cells every 28 days. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to lenalidomide (160 patients) or placebo (79 patients), given once daily for 28-day cycles. Patients whose creatinine clearance was 40-60 mL/min received 5 mg lenalidomide, while the rest received 10 mg. Randomization was stratified based on MDS treatment history, baseline transfusion requirements, and time from MDS diagnosis (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0118). A total of 43 lenalidomide patients (27%) and 2 placebo patients (2.5%; P less than .001) did not require packed red blood cell transfusions for at least 8 weeks. Transfusion independence persisted through 24 weeks for 17% of lenalidomide patients and no placebo patients. Of 39 patients given 5-mg lenalidomide, 18% reached the primary endpoint (P = .006, compared with placebo). The median duration of response was nearly 31 weeks (95% confidence interval, 21-59 weeks). Prior use of ESAs was the only significant predictor of response in the multivariate analysis (odds ratio, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.1; P = .01), although low baseline transfusion burden reached significance in the univariate model and borderline significance in the multivariate model (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 0.96-7.6; P = .06).

The highest response rate (43%) occurred among the 40 patients who had previously received ESAs and had a baseline erythropoietin level under 100 mU/mL. The response rates for other patients previously treated with ESAs fell as baseline EPO level increased, and the response rate was only 9% among patients whose relatively high endogenous EPO level had made them ineligible for ESA treatment. “Patients with higher endogenous EPO levels may be less responsive due to marked intrinsic defects in erythroid signaling pathways, including signal transducer and activator of transcription extracellular regulated kinase 1/2, and lipid raft assembly, which are restored or stimulated by lenalidomide exposure,” the researchers wrote.

As in previous studies, grade 3-4 adverse events with lenalidomide usually were due to myelosuppression. Grade 3-4 neutropenia affected 99 lenalidomide patients (62%) and 10 placebo patients (13%). Grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia affected 57 lenalidomide patients (36%) and 3 placebo patients (4%). Lenalidomide was associated with a 3% rate of venous thrombosis but did not cause detectable pulmonary embolism. Lenalidomide was stopped in 32% of patients because of thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, or other adverse events, compared with 11% of placebo patients. In all, 2.5% of patients in each group died while on treatment.

Celgene makes lenalidomide and funded the study. Dr. Santini disclosed consulting or advisory roles and honoraria from Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Seventeen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Celgene.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lenalidomide usually does not free patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who are refractory to or ineligible for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents from needing packed red blood cell transfusions.

Major finding: A total of 27% of lenalidomide-treated and 2.5% of placebo-treated patients did not need transfusions for at least 8 weeks while on treatment (P less than .001).

Data source: An international randomized, double-blind phase III study of 239 adults with non-del(5q) MDS who were ineligible for or refractory to ESAs.

Disclosures: Celgene makes lenalidomide and funded the study. Dr. Santini disclosed consulting or advisory roles and honoraria from Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Seventeen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Celgene.

Study: CMV doesn’t lower risk of relapse, death

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

Drug enables transfusion independence in lower-risk MDS

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

ESA benefits lower-risk MDS patients

COPENHAGEN—The erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) darbepoetin alfa can provide a clinical benefit in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), a phase 3 trial suggests.

In the ARCADE trial, darbepoetin alfa significantly reduced the incidence of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in patients with low- and intermediate-1 risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), when compared to placebo.

The ESA also significantly improved erythroid response.

In addition, researchers said adverse events (AEs) were generally balanced between the darbepoetin alfa and placebo arms.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus Dresden in Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S128). The ARCADE trial was sponsored by Amgen.

Dr Platzbecker noted that, although ESAs are recommended in clinical guidelines to treat anemia in patients with lower-risk MDS, the drugs are not widely approved for this indication.