User login

New tests may finally diagnose long COVID

One of the biggest challenges facing clinicians who treat long COVID is a lack of consensus when it comes to recognizing and diagnosing the condition. But

Effective diagnostic testing would be a game-changer in the long COVID fight, for it’s not just the fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations, and other persistent symptoms that affect patients. Two out of three people with long COVID also suffer mental health challenges like depression and anxiety. Some patients say their symptoms are not taken seriously by their doctors. And as many as 12% of long COVID patients are unemployed because of the severity of their illness and their employers may be skeptical of their condition.

Quick, accurate diagnosis would eliminate all that. Now a new preprint study suggests that the elevation of certain immune system proteins are a commonality in long COVID patients and identifying them may be an accurate way to diagnose the condition.

Researchers at Cardiff (Wales) University, tracked 166 patients, 79 of whom had been diagnosed with long COVID and 87 who had not. All participants had recovered from a severe bout of acute COVID-19.

In an analysis of the blood plasma of the study participants, researchers found elevated levels of certain components. Four proteins in particular – Ba, iC3b, C5a, and TCC – predicted the presence of long COVID with 78.5% accuracy.

“I was gobsmacked by the results. We’re seeing a massive dysregulation in those four biomarkers,” says study author Wioleta Zelek, PhD, a research fellow at Cardiff University. “It’s a combination that we showed was predictive of long COVID.”

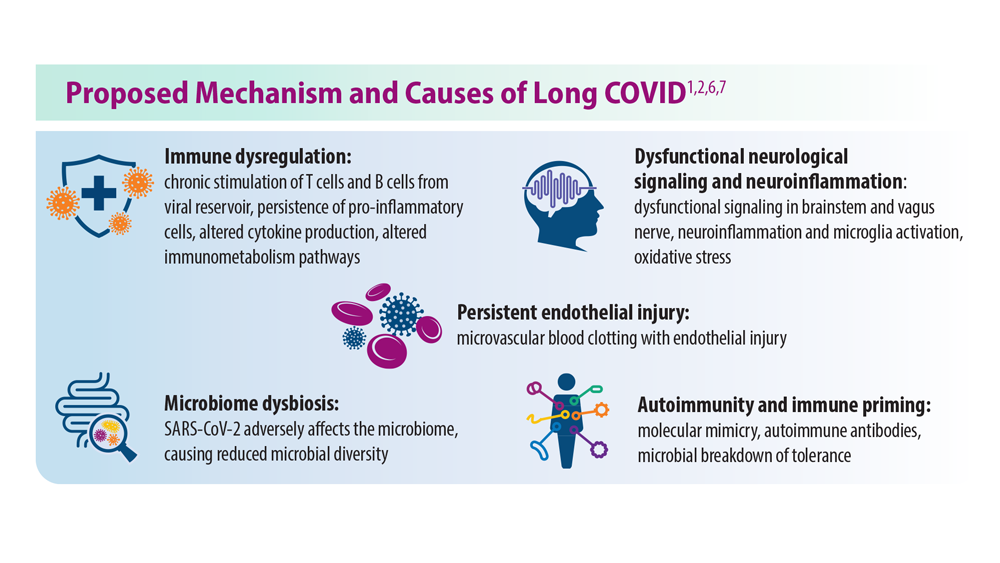

The study revealed that long COVID was associated with inflammation of the immune system causing these complement proteins to remain dysregulated. Proteins like C3, C4, and C5 are important parts of the immune system because they recruit phagocytes, cells that attack and engulf bacteria and viruses at the site of infection to destroy pathogens like SARS-coV-2.

In the case of long COVID, these proteins remain chronically elevated. While the symptoms of long COVID have seemed largely unrelated to one another, researchers point to elevated inflammation as a connecting factor that causes various systems in the body to go haywire.

“Anything that could help to better diagnose patients with long COVID is research we’re greatly appreciative of within the clinical community,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the University of California, Los Angeles, Long COVID program at UCLA Health.

Testing for biomarkers highlighted in the study, as well as others like serotonin and cortisol, may help doctors separate patients who have long COVID from patients who have similar symptoms caused by other conditions, said Dr. Viswanathan. For example, a recent study published in the journal Cell found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but recovered from the condition.

Dr. Viswanathan cautions that the biomarker test does not answer all the questions about diagnosing long COVID. For example, Dr. Viswanathan said scientists don’t know whether complement dysregulation is caused by long COVID and not another underlying medical issue that patients had prior to infection, because “we don’t know where patients’ levels were prior to developing long COVID.” For example, those with autoimmune issues are more likely to develop long COVID, which means their levels could have been elevated prior to a COVID infection.

It is increasingly likely, said Dr. Viswanathan, that long COVID is an umbrella term for a host of conditions that could be caused by different impacts of the virus. Other research has pointed to the different phenotypes of long COVID. For example, some are focused on cardiopulmonary issues and others on fatigue and gastrointestinal problems.

“It looks like these different phenotypes have a different mechanism for disease,” she said. This means that it’s less likely to be a one-size-fits-all condition and the next step in the research should be identifying which biomarker is aligned with which phenotype of the disease.

Better diagnostics will open the door to better treatments, Dr. Zelek said. The more doctors understand about the mechanism causing immune dysregulation in long COVID patients, the more they can treat it with existing medications. Dr. Zelek’s lab has been studying certain medications like pegcetacoplan (C3 blocker), danicopan (anti-factor D), and iptacopan (anti-factor B) that can be used to break the body’s cycle of inflammation and reduce symptoms experienced in those with long COVID.

These drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of a rare blood disease called paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. The C5 inhibitor zilucoplan has also been used in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and researchers have found that the drug lowered serum C5 and interleukin-8 concentration in the blood, seeming to reduce certain aspects of the immune system’s inflammatory response to the virus.

The Cardiff University research is one of the most detailed studies to highlight long COVID biomarkers to date, said infectious disease specialist Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. The research needs to be duplicated in a larger study population that might include the other biomarkers like serotonin and cortisol to see if they’re related, she said.

Researchers are learning more everyday about the various biomarkers that may be linked to long COVID, she added. This Cardiff study showed that a huge percentage of those patients had elevated levels of certain complements. The next step, said Dr. McComsey, “is to put all these puzzle pieces together” so that clinicians have a common diagnostic tool or tools that provide patients with some peace of mind in starting their road to recovery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest challenges facing clinicians who treat long COVID is a lack of consensus when it comes to recognizing and diagnosing the condition. But

Effective diagnostic testing would be a game-changer in the long COVID fight, for it’s not just the fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations, and other persistent symptoms that affect patients. Two out of three people with long COVID also suffer mental health challenges like depression and anxiety. Some patients say their symptoms are not taken seriously by their doctors. And as many as 12% of long COVID patients are unemployed because of the severity of their illness and their employers may be skeptical of their condition.

Quick, accurate diagnosis would eliminate all that. Now a new preprint study suggests that the elevation of certain immune system proteins are a commonality in long COVID patients and identifying them may be an accurate way to diagnose the condition.

Researchers at Cardiff (Wales) University, tracked 166 patients, 79 of whom had been diagnosed with long COVID and 87 who had not. All participants had recovered from a severe bout of acute COVID-19.

In an analysis of the blood plasma of the study participants, researchers found elevated levels of certain components. Four proteins in particular – Ba, iC3b, C5a, and TCC – predicted the presence of long COVID with 78.5% accuracy.

“I was gobsmacked by the results. We’re seeing a massive dysregulation in those four biomarkers,” says study author Wioleta Zelek, PhD, a research fellow at Cardiff University. “It’s a combination that we showed was predictive of long COVID.”

The study revealed that long COVID was associated with inflammation of the immune system causing these complement proteins to remain dysregulated. Proteins like C3, C4, and C5 are important parts of the immune system because they recruit phagocytes, cells that attack and engulf bacteria and viruses at the site of infection to destroy pathogens like SARS-coV-2.

In the case of long COVID, these proteins remain chronically elevated. While the symptoms of long COVID have seemed largely unrelated to one another, researchers point to elevated inflammation as a connecting factor that causes various systems in the body to go haywire.

“Anything that could help to better diagnose patients with long COVID is research we’re greatly appreciative of within the clinical community,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the University of California, Los Angeles, Long COVID program at UCLA Health.

Testing for biomarkers highlighted in the study, as well as others like serotonin and cortisol, may help doctors separate patients who have long COVID from patients who have similar symptoms caused by other conditions, said Dr. Viswanathan. For example, a recent study published in the journal Cell found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but recovered from the condition.

Dr. Viswanathan cautions that the biomarker test does not answer all the questions about diagnosing long COVID. For example, Dr. Viswanathan said scientists don’t know whether complement dysregulation is caused by long COVID and not another underlying medical issue that patients had prior to infection, because “we don’t know where patients’ levels were prior to developing long COVID.” For example, those with autoimmune issues are more likely to develop long COVID, which means their levels could have been elevated prior to a COVID infection.

It is increasingly likely, said Dr. Viswanathan, that long COVID is an umbrella term for a host of conditions that could be caused by different impacts of the virus. Other research has pointed to the different phenotypes of long COVID. For example, some are focused on cardiopulmonary issues and others on fatigue and gastrointestinal problems.

“It looks like these different phenotypes have a different mechanism for disease,” she said. This means that it’s less likely to be a one-size-fits-all condition and the next step in the research should be identifying which biomarker is aligned with which phenotype of the disease.

Better diagnostics will open the door to better treatments, Dr. Zelek said. The more doctors understand about the mechanism causing immune dysregulation in long COVID patients, the more they can treat it with existing medications. Dr. Zelek’s lab has been studying certain medications like pegcetacoplan (C3 blocker), danicopan (anti-factor D), and iptacopan (anti-factor B) that can be used to break the body’s cycle of inflammation and reduce symptoms experienced in those with long COVID.

These drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of a rare blood disease called paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. The C5 inhibitor zilucoplan has also been used in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and researchers have found that the drug lowered serum C5 and interleukin-8 concentration in the blood, seeming to reduce certain aspects of the immune system’s inflammatory response to the virus.

The Cardiff University research is one of the most detailed studies to highlight long COVID biomarkers to date, said infectious disease specialist Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. The research needs to be duplicated in a larger study population that might include the other biomarkers like serotonin and cortisol to see if they’re related, she said.

Researchers are learning more everyday about the various biomarkers that may be linked to long COVID, she added. This Cardiff study showed that a huge percentage of those patients had elevated levels of certain complements. The next step, said Dr. McComsey, “is to put all these puzzle pieces together” so that clinicians have a common diagnostic tool or tools that provide patients with some peace of mind in starting their road to recovery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest challenges facing clinicians who treat long COVID is a lack of consensus when it comes to recognizing and diagnosing the condition. But

Effective diagnostic testing would be a game-changer in the long COVID fight, for it’s not just the fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations, and other persistent symptoms that affect patients. Two out of three people with long COVID also suffer mental health challenges like depression and anxiety. Some patients say their symptoms are not taken seriously by their doctors. And as many as 12% of long COVID patients are unemployed because of the severity of their illness and their employers may be skeptical of their condition.

Quick, accurate diagnosis would eliminate all that. Now a new preprint study suggests that the elevation of certain immune system proteins are a commonality in long COVID patients and identifying them may be an accurate way to diagnose the condition.

Researchers at Cardiff (Wales) University, tracked 166 patients, 79 of whom had been diagnosed with long COVID and 87 who had not. All participants had recovered from a severe bout of acute COVID-19.

In an analysis of the blood plasma of the study participants, researchers found elevated levels of certain components. Four proteins in particular – Ba, iC3b, C5a, and TCC – predicted the presence of long COVID with 78.5% accuracy.

“I was gobsmacked by the results. We’re seeing a massive dysregulation in those four biomarkers,” says study author Wioleta Zelek, PhD, a research fellow at Cardiff University. “It’s a combination that we showed was predictive of long COVID.”

The study revealed that long COVID was associated with inflammation of the immune system causing these complement proteins to remain dysregulated. Proteins like C3, C4, and C5 are important parts of the immune system because they recruit phagocytes, cells that attack and engulf bacteria and viruses at the site of infection to destroy pathogens like SARS-coV-2.

In the case of long COVID, these proteins remain chronically elevated. While the symptoms of long COVID have seemed largely unrelated to one another, researchers point to elevated inflammation as a connecting factor that causes various systems in the body to go haywire.

“Anything that could help to better diagnose patients with long COVID is research we’re greatly appreciative of within the clinical community,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the University of California, Los Angeles, Long COVID program at UCLA Health.

Testing for biomarkers highlighted in the study, as well as others like serotonin and cortisol, may help doctors separate patients who have long COVID from patients who have similar symptoms caused by other conditions, said Dr. Viswanathan. For example, a recent study published in the journal Cell found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but recovered from the condition.

Dr. Viswanathan cautions that the biomarker test does not answer all the questions about diagnosing long COVID. For example, Dr. Viswanathan said scientists don’t know whether complement dysregulation is caused by long COVID and not another underlying medical issue that patients had prior to infection, because “we don’t know where patients’ levels were prior to developing long COVID.” For example, those with autoimmune issues are more likely to develop long COVID, which means their levels could have been elevated prior to a COVID infection.

It is increasingly likely, said Dr. Viswanathan, that long COVID is an umbrella term for a host of conditions that could be caused by different impacts of the virus. Other research has pointed to the different phenotypes of long COVID. For example, some are focused on cardiopulmonary issues and others on fatigue and gastrointestinal problems.

“It looks like these different phenotypes have a different mechanism for disease,” she said. This means that it’s less likely to be a one-size-fits-all condition and the next step in the research should be identifying which biomarker is aligned with which phenotype of the disease.

Better diagnostics will open the door to better treatments, Dr. Zelek said. The more doctors understand about the mechanism causing immune dysregulation in long COVID patients, the more they can treat it with existing medications. Dr. Zelek’s lab has been studying certain medications like pegcetacoplan (C3 blocker), danicopan (anti-factor D), and iptacopan (anti-factor B) that can be used to break the body’s cycle of inflammation and reduce symptoms experienced in those with long COVID.

These drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of a rare blood disease called paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. The C5 inhibitor zilucoplan has also been used in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and researchers have found that the drug lowered serum C5 and interleukin-8 concentration in the blood, seeming to reduce certain aspects of the immune system’s inflammatory response to the virus.

The Cardiff University research is one of the most detailed studies to highlight long COVID biomarkers to date, said infectious disease specialist Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. The research needs to be duplicated in a larger study population that might include the other biomarkers like serotonin and cortisol to see if they’re related, she said.

Researchers are learning more everyday about the various biomarkers that may be linked to long COVID, she added. This Cardiff study showed that a huge percentage of those patients had elevated levels of certain complements. The next step, said Dr. McComsey, “is to put all these puzzle pieces together” so that clinicians have a common diagnostic tool or tools that provide patients with some peace of mind in starting their road to recovery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MEDRXIV

Chest pain with long COVID common but undertreated

And chronic chest discomfort may persist in some individuals for years after COVID, warranting future studies of reliable treatments and pain management in this population, a new study shows.

“Recent studies have shown that chest pain occurs in as many as 89% of patients who qualify as having long COVID,” said Ansley Poole, an undergraduate student at the University of South Florida, Tampa, who conducted the research under the supervision of Christine Hunt, DO, and her colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings, though preliminary, shed light on the prevalence, current treatments, and ongoing challenges in managing symptoms of long COVID, said Ms. Poole, who presented the research at the annual Pain Medicine Meeting sponsored by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

Long COVID, which affects an estimated 18 million Americans, manifests approximately 12 weeks after the initial infection and can persist for 2 months or more. Ms. Poole and her team set out to identify risk factors, treatment options, and outcomes for patients dealing with post-COVID chest discomfort.

The study involved a retrospective chart review of 520 patients from the Mayo Clinic network, narrowed down to a final sample of 104. To be included, patients had to report chest discomfort 3-6 months post COVID that continued for 3-6 months after presentation, with no history of chronic chest pain before the infection.

The researchers identified no standardized method for the treatment or management of chest pain linked to long COVID. “Patients were prescribed multiple different treatments, including opioids, post-COVID treatment programs, anticoagulants, steroids, and even psychological programs,” Ms. Poole said.

The median age of the patients was around 50 years; more than 65% were female and over 90% identified as White. More than half (55%) had received one or more vaccine doses at the time of infection. The majority were classified as overweight or obese at the time of their SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Of the 104 patients analyzed, 30 were referred to one or more subspecialties within the pain medicine department, 23 were hospitalized, and 9 were admitted to the intensive care unit or critical care.

“Fifty-three of our patients visited the ER one or more times after COVID because of chest discomfort; however, only six were admitted for over 24 hours, indicating possible overuse of emergency services,” Ms. Poole noted.

Overall, chest pain was described as intermittent instead of constant, which may have been a barrier to providing adequate and timely treatment. The inconsistent presence of pain contributed to the prolonged suffering some patients experienced, Ms. Poole noted.

The study identified several comorbidities, potentially complicating the treatment and etiology of chest pain. These comorbidities – when combined with COVID-related chest pain – contributed to the wide array of prescribed treatments, including steroids, anticoagulants, beta blockers, and physical therapy. Chest pain also seldom stood alone; it was often accompanied by other long COVID–related symptoms, such as shortness of breath.

“Our current analysis indicates that chest pain continues on for years in many individuals, suggesting that COVID-related chest pain may be resistant to treatment,” Ms. Poole reported.

The observed heterogeneity in treatments and outcomes in patients experiencing long-term chest discomfort after COVID infection underscores the need for future studies to establish reliable treatment and management protocols for this population, said Dalia Elmofty, MD, an associate professor of anesthesia and critical care at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study. “There are things about COVID that we don’t fully understand. As we’re seeing its consequences and trying to understand its etiology, we recognize the need for further research,” Dr. Elmofty said.

“So many different disease pathologies came out of COVID, whether it’s organ pathology, myofascial pathology, or autoimmune pathology, and all of that is obviously linked to pain,” Dr. Elmofty told this news organization. “It’s an area of research that we are going to have to devote a lot of time to in order to understand, but I think we’re still in the very early phases, trying to fit the pieces of the puzzle together.”

Ms. Poole and Dr. Elmofty report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

And chronic chest discomfort may persist in some individuals for years after COVID, warranting future studies of reliable treatments and pain management in this population, a new study shows.

“Recent studies have shown that chest pain occurs in as many as 89% of patients who qualify as having long COVID,” said Ansley Poole, an undergraduate student at the University of South Florida, Tampa, who conducted the research under the supervision of Christine Hunt, DO, and her colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings, though preliminary, shed light on the prevalence, current treatments, and ongoing challenges in managing symptoms of long COVID, said Ms. Poole, who presented the research at the annual Pain Medicine Meeting sponsored by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

Long COVID, which affects an estimated 18 million Americans, manifests approximately 12 weeks after the initial infection and can persist for 2 months or more. Ms. Poole and her team set out to identify risk factors, treatment options, and outcomes for patients dealing with post-COVID chest discomfort.

The study involved a retrospective chart review of 520 patients from the Mayo Clinic network, narrowed down to a final sample of 104. To be included, patients had to report chest discomfort 3-6 months post COVID that continued for 3-6 months after presentation, with no history of chronic chest pain before the infection.

The researchers identified no standardized method for the treatment or management of chest pain linked to long COVID. “Patients were prescribed multiple different treatments, including opioids, post-COVID treatment programs, anticoagulants, steroids, and even psychological programs,” Ms. Poole said.

The median age of the patients was around 50 years; more than 65% were female and over 90% identified as White. More than half (55%) had received one or more vaccine doses at the time of infection. The majority were classified as overweight or obese at the time of their SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Of the 104 patients analyzed, 30 were referred to one or more subspecialties within the pain medicine department, 23 were hospitalized, and 9 were admitted to the intensive care unit or critical care.

“Fifty-three of our patients visited the ER one or more times after COVID because of chest discomfort; however, only six were admitted for over 24 hours, indicating possible overuse of emergency services,” Ms. Poole noted.

Overall, chest pain was described as intermittent instead of constant, which may have been a barrier to providing adequate and timely treatment. The inconsistent presence of pain contributed to the prolonged suffering some patients experienced, Ms. Poole noted.

The study identified several comorbidities, potentially complicating the treatment and etiology of chest pain. These comorbidities – when combined with COVID-related chest pain – contributed to the wide array of prescribed treatments, including steroids, anticoagulants, beta blockers, and physical therapy. Chest pain also seldom stood alone; it was often accompanied by other long COVID–related symptoms, such as shortness of breath.

“Our current analysis indicates that chest pain continues on for years in many individuals, suggesting that COVID-related chest pain may be resistant to treatment,” Ms. Poole reported.

The observed heterogeneity in treatments and outcomes in patients experiencing long-term chest discomfort after COVID infection underscores the need for future studies to establish reliable treatment and management protocols for this population, said Dalia Elmofty, MD, an associate professor of anesthesia and critical care at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study. “There are things about COVID that we don’t fully understand. As we’re seeing its consequences and trying to understand its etiology, we recognize the need for further research,” Dr. Elmofty said.

“So many different disease pathologies came out of COVID, whether it’s organ pathology, myofascial pathology, or autoimmune pathology, and all of that is obviously linked to pain,” Dr. Elmofty told this news organization. “It’s an area of research that we are going to have to devote a lot of time to in order to understand, but I think we’re still in the very early phases, trying to fit the pieces of the puzzle together.”

Ms. Poole and Dr. Elmofty report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

And chronic chest discomfort may persist in some individuals for years after COVID, warranting future studies of reliable treatments and pain management in this population, a new study shows.

“Recent studies have shown that chest pain occurs in as many as 89% of patients who qualify as having long COVID,” said Ansley Poole, an undergraduate student at the University of South Florida, Tampa, who conducted the research under the supervision of Christine Hunt, DO, and her colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings, though preliminary, shed light on the prevalence, current treatments, and ongoing challenges in managing symptoms of long COVID, said Ms. Poole, who presented the research at the annual Pain Medicine Meeting sponsored by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

Long COVID, which affects an estimated 18 million Americans, manifests approximately 12 weeks after the initial infection and can persist for 2 months or more. Ms. Poole and her team set out to identify risk factors, treatment options, and outcomes for patients dealing with post-COVID chest discomfort.

The study involved a retrospective chart review of 520 patients from the Mayo Clinic network, narrowed down to a final sample of 104. To be included, patients had to report chest discomfort 3-6 months post COVID that continued for 3-6 months after presentation, with no history of chronic chest pain before the infection.

The researchers identified no standardized method for the treatment or management of chest pain linked to long COVID. “Patients were prescribed multiple different treatments, including opioids, post-COVID treatment programs, anticoagulants, steroids, and even psychological programs,” Ms. Poole said.

The median age of the patients was around 50 years; more than 65% were female and over 90% identified as White. More than half (55%) had received one or more vaccine doses at the time of infection. The majority were classified as overweight or obese at the time of their SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Of the 104 patients analyzed, 30 were referred to one or more subspecialties within the pain medicine department, 23 were hospitalized, and 9 were admitted to the intensive care unit or critical care.

“Fifty-three of our patients visited the ER one or more times after COVID because of chest discomfort; however, only six were admitted for over 24 hours, indicating possible overuse of emergency services,” Ms. Poole noted.

Overall, chest pain was described as intermittent instead of constant, which may have been a barrier to providing adequate and timely treatment. The inconsistent presence of pain contributed to the prolonged suffering some patients experienced, Ms. Poole noted.

The study identified several comorbidities, potentially complicating the treatment and etiology of chest pain. These comorbidities – when combined with COVID-related chest pain – contributed to the wide array of prescribed treatments, including steroids, anticoagulants, beta blockers, and physical therapy. Chest pain also seldom stood alone; it was often accompanied by other long COVID–related symptoms, such as shortness of breath.

“Our current analysis indicates that chest pain continues on for years in many individuals, suggesting that COVID-related chest pain may be resistant to treatment,” Ms. Poole reported.

The observed heterogeneity in treatments and outcomes in patients experiencing long-term chest discomfort after COVID infection underscores the need for future studies to establish reliable treatment and management protocols for this population, said Dalia Elmofty, MD, an associate professor of anesthesia and critical care at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study. “There are things about COVID that we don’t fully understand. As we’re seeing its consequences and trying to understand its etiology, we recognize the need for further research,” Dr. Elmofty said.

“So many different disease pathologies came out of COVID, whether it’s organ pathology, myofascial pathology, or autoimmune pathology, and all of that is obviously linked to pain,” Dr. Elmofty told this news organization. “It’s an area of research that we are going to have to devote a lot of time to in order to understand, but I think we’re still in the very early phases, trying to fit the pieces of the puzzle together.”

Ms. Poole and Dr. Elmofty report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID and mental illness: New guidance

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

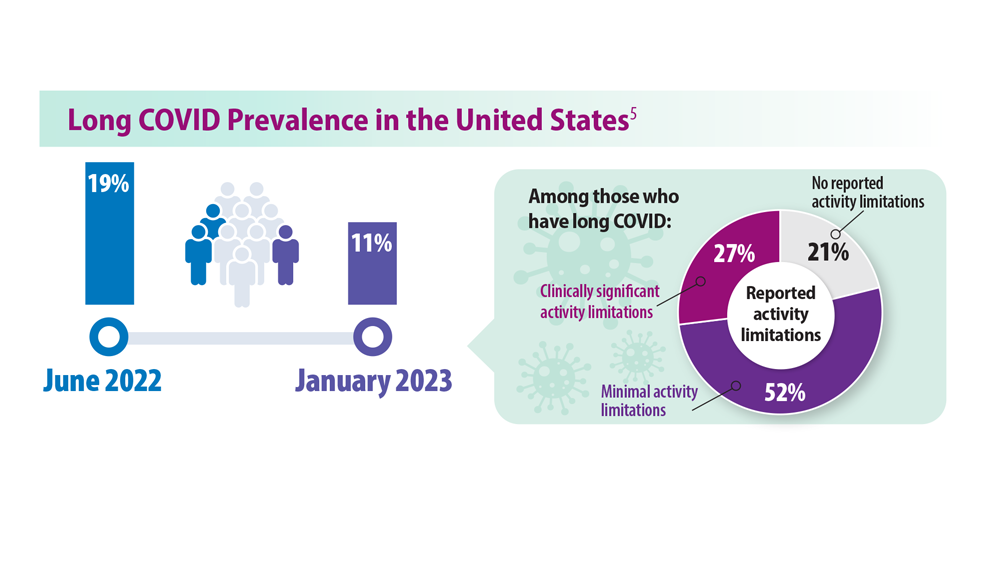

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PHYSICAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION

Sensory comeback: New findings show the path to smell and taste recovery after COVID

Good news for people struggling with sensory problems after a bout of COVID-19. Although mild cases of the disease often impair the ability to taste and smell, and the problem can drag on for months, a new study from Italy shows that most people return to their senses, as it were, within 3 years.

said Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, MD, a professor of medicine, surgery, and health sciences at the University of Trieste (Italy), and a co-author of the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Dr. Boscolo-Rizzo and his colleagues analyzed data from 88 adults with mild COVID-19, which was defined as having no lower respiratory disease and blood oxygen saturation of 94% or greater. Another group of 88 adults who never contracted the virus but sometimes had difficulties with smell and taste were also studied. In both groups, the average age was 49 years, all participants were White, and 58% were women.

The researchers tested participants’ sense of smell with sticks that contained different odors and checked their sense of taste with strips that had different tastes. Over time, fewer people had difficulty distinguishing odors. Three years after developing COVID-19, only 12 people had impaired smell, compared with 36 people at year 1 and 24 people at year 2. And at the 3-year mark, all participants had at least a partial ability to smell.

The story was similar with sense of taste, with 10 of 88 people reporting impairments 3 years later. By then, people with COVID-19 were no more likely to have trouble with smell or taste than people who did not get the virus.

A study this past June showed a strong correlation between severity of COVID-19 symptoms and impaired sense of taste and smell and estimated that millions of Americans maintained altered senses. More than 10% of people in the Italian study still had trouble with smell or taste 3 years later.

Emerging treatments, psychological concerns

“We’re seeing fewer people with this problem, but there are still people suffering from it,” said Fernando Carnavali, MD, an internal medicine physician and a site director for the Center for Post-COVID Care at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Dr. Carnavali wasn’t part of this study, but he did find the new results encouraging, and he called for similar studies in diverse populations that have experienced COVID-19. He also noted that an impaired sense of smell is distressing.

“It really has a significant psychological impact,” Dr. Carnavali said.

He recalled a patient crying in his office because her inability to smell made it impossible for her to cook. Dr. Carnavali recommended clinicians refer patients facing protracted loss of smell or taste to mental health professionals for support.

Treatments are emerging for COVID-19 smell loss. One approach is to inject platelet-rich plasma into a patient’s nasal cavities to help neurons related to smell repair themselves.

A randomized trial showed platelet-rich plasma significantly outperformed placebo in patients with smell loss up to a year after getting COVID-19.

“I wish more people would do it,” said Zara Patel, MD, an otolaryngologist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine, who helped conduct that trial. She said some physicians may be nervous about injecting plasma so close to the skull and are therefore hesitant to try this approach.

Another technique may help to address the olfactory condition known as parosmia, in which patients generally experience a benign odor as rancid, according to otolaryngologist Nyssa Farrell, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Farrell said around two-thirds of patients who contract COVID-19 develop the condition, and the rates of long-term parosmia range from 10%-50% depending on various studies.

“It is almost always foul; this can profoundly affect someone’s quality of life,” impairing their ability to eat or to be intimate with a partner who now smells unpleasant, said Dr. Farrell, who wasn’t associated with this research.

The treatment, called a stellate ganglion block, is provided through a shot into nerves in the neck. People with parosmia associated with COVID-19 often report that this method cures them. Dr. Patel said that may be because their psychological health is improving, not their sense of smell, because the area of the body where the stellate ganglion block is applied is not part of the olfactory system.

Earlier this year, Dr. Farrell and colleagues reported that parosmia linked to COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

One coauthor reported receiving grants from Smell and Taste Lab, Takasago, Baia Foods, and Frequency Therapeutics. The other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Good news for people struggling with sensory problems after a bout of COVID-19. Although mild cases of the disease often impair the ability to taste and smell, and the problem can drag on for months, a new study from Italy shows that most people return to their senses, as it were, within 3 years.

said Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, MD, a professor of medicine, surgery, and health sciences at the University of Trieste (Italy), and a co-author of the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Dr. Boscolo-Rizzo and his colleagues analyzed data from 88 adults with mild COVID-19, which was defined as having no lower respiratory disease and blood oxygen saturation of 94% or greater. Another group of 88 adults who never contracted the virus but sometimes had difficulties with smell and taste were also studied. In both groups, the average age was 49 years, all participants were White, and 58% were women.

The researchers tested participants’ sense of smell with sticks that contained different odors and checked their sense of taste with strips that had different tastes. Over time, fewer people had difficulty distinguishing odors. Three years after developing COVID-19, only 12 people had impaired smell, compared with 36 people at year 1 and 24 people at year 2. And at the 3-year mark, all participants had at least a partial ability to smell.

The story was similar with sense of taste, with 10 of 88 people reporting impairments 3 years later. By then, people with COVID-19 were no more likely to have trouble with smell or taste than people who did not get the virus.

A study this past June showed a strong correlation between severity of COVID-19 symptoms and impaired sense of taste and smell and estimated that millions of Americans maintained altered senses. More than 10% of people in the Italian study still had trouble with smell or taste 3 years later.

Emerging treatments, psychological concerns

“We’re seeing fewer people with this problem, but there are still people suffering from it,” said Fernando Carnavali, MD, an internal medicine physician and a site director for the Center for Post-COVID Care at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Dr. Carnavali wasn’t part of this study, but he did find the new results encouraging, and he called for similar studies in diverse populations that have experienced COVID-19. He also noted that an impaired sense of smell is distressing.

“It really has a significant psychological impact,” Dr. Carnavali said.

He recalled a patient crying in his office because her inability to smell made it impossible for her to cook. Dr. Carnavali recommended clinicians refer patients facing protracted loss of smell or taste to mental health professionals for support.

Treatments are emerging for COVID-19 smell loss. One approach is to inject platelet-rich plasma into a patient’s nasal cavities to help neurons related to smell repair themselves.

A randomized trial showed platelet-rich plasma significantly outperformed placebo in patients with smell loss up to a year after getting COVID-19.

“I wish more people would do it,” said Zara Patel, MD, an otolaryngologist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine, who helped conduct that trial. She said some physicians may be nervous about injecting plasma so close to the skull and are therefore hesitant to try this approach.

Another technique may help to address the olfactory condition known as parosmia, in which patients generally experience a benign odor as rancid, according to otolaryngologist Nyssa Farrell, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Farrell said around two-thirds of patients who contract COVID-19 develop the condition, and the rates of long-term parosmia range from 10%-50% depending on various studies.

“It is almost always foul; this can profoundly affect someone’s quality of life,” impairing their ability to eat or to be intimate with a partner who now smells unpleasant, said Dr. Farrell, who wasn’t associated with this research.

The treatment, called a stellate ganglion block, is provided through a shot into nerves in the neck. People with parosmia associated with COVID-19 often report that this method cures them. Dr. Patel said that may be because their psychological health is improving, not their sense of smell, because the area of the body where the stellate ganglion block is applied is not part of the olfactory system.

Earlier this year, Dr. Farrell and colleagues reported that parosmia linked to COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

One coauthor reported receiving grants from Smell and Taste Lab, Takasago, Baia Foods, and Frequency Therapeutics. The other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Good news for people struggling with sensory problems after a bout of COVID-19. Although mild cases of the disease often impair the ability to taste and smell, and the problem can drag on for months, a new study from Italy shows that most people return to their senses, as it were, within 3 years.

said Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, MD, a professor of medicine, surgery, and health sciences at the University of Trieste (Italy), and a co-author of the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Dr. Boscolo-Rizzo and his colleagues analyzed data from 88 adults with mild COVID-19, which was defined as having no lower respiratory disease and blood oxygen saturation of 94% or greater. Another group of 88 adults who never contracted the virus but sometimes had difficulties with smell and taste were also studied. In both groups, the average age was 49 years, all participants were White, and 58% were women.

The researchers tested participants’ sense of smell with sticks that contained different odors and checked their sense of taste with strips that had different tastes. Over time, fewer people had difficulty distinguishing odors. Three years after developing COVID-19, only 12 people had impaired smell, compared with 36 people at year 1 and 24 people at year 2. And at the 3-year mark, all participants had at least a partial ability to smell.

The story was similar with sense of taste, with 10 of 88 people reporting impairments 3 years later. By then, people with COVID-19 were no more likely to have trouble with smell or taste than people who did not get the virus.

A study this past June showed a strong correlation between severity of COVID-19 symptoms and impaired sense of taste and smell and estimated that millions of Americans maintained altered senses. More than 10% of people in the Italian study still had trouble with smell or taste 3 years later.

Emerging treatments, psychological concerns

“We’re seeing fewer people with this problem, but there are still people suffering from it,” said Fernando Carnavali, MD, an internal medicine physician and a site director for the Center for Post-COVID Care at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Dr. Carnavali wasn’t part of this study, but he did find the new results encouraging, and he called for similar studies in diverse populations that have experienced COVID-19. He also noted that an impaired sense of smell is distressing.

“It really has a significant psychological impact,” Dr. Carnavali said.

He recalled a patient crying in his office because her inability to smell made it impossible for her to cook. Dr. Carnavali recommended clinicians refer patients facing protracted loss of smell or taste to mental health professionals for support.

Treatments are emerging for COVID-19 smell loss. One approach is to inject platelet-rich plasma into a patient’s nasal cavities to help neurons related to smell repair themselves.

A randomized trial showed platelet-rich plasma significantly outperformed placebo in patients with smell loss up to a year after getting COVID-19.

“I wish more people would do it,” said Zara Patel, MD, an otolaryngologist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine, who helped conduct that trial. She said some physicians may be nervous about injecting plasma so close to the skull and are therefore hesitant to try this approach.

Another technique may help to address the olfactory condition known as parosmia, in which patients generally experience a benign odor as rancid, according to otolaryngologist Nyssa Farrell, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Farrell said around two-thirds of patients who contract COVID-19 develop the condition, and the rates of long-term parosmia range from 10%-50% depending on various studies.

“It is almost always foul; this can profoundly affect someone’s quality of life,” impairing their ability to eat or to be intimate with a partner who now smells unpleasant, said Dr. Farrell, who wasn’t associated with this research.

The treatment, called a stellate ganglion block, is provided through a shot into nerves in the neck. People with parosmia associated with COVID-19 often report that this method cures them. Dr. Patel said that may be because their psychological health is improving, not their sense of smell, because the area of the body where the stellate ganglion block is applied is not part of the olfactory system.

Earlier this year, Dr. Farrell and colleagues reported that parosmia linked to COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

One coauthor reported receiving grants from Smell and Taste Lab, Takasago, Baia Foods, and Frequency Therapeutics. The other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD & NECK SURGERY

A new long COVID explanation: Low serotonin levels?

Could antidepressants hold the key to treating long COVID? The study even points to a possible treatment.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that has many functions in the body and is targeted by the most commonly prescribed antidepressants – the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Serotonin is widely studied for its effects on the brain – it regulates the messaging between neurons, affecting sleep, mood, and memory. It is present in the gut, is found in cells along the gastrointestinal tract, and is absorbed by blood platelets. Gut serotonin, known as circulating serotonin, is responsible for a host of other functions, including the regulation of blood flow, body temperature, and digestion.

Low levels of serotonin could result in any number of seemingly unrelated symptoms, as in the case of long COVID, experts say. The condition affects about 7% of Americans and is associated with a wide range of health problems, including fatigue, shortness of breath, neurological symptoms, joint pain, blood clots, heart palpitations, and digestive problems.

Long COVID is difficult to treat because researchers haven’t been able to pinpoint the underlying mechanisms that cause prolonged illness after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, said study author Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The hope is that this study could have implications for new treatments, he said.

“Long COVID can have manifestations not only in the brain but in many different parts of the body, so it’s possible that serotonin reductions are involved in many different aspects of the disease,” said Dr. Thaiss.

Dr. Thaiss’s study, published in the journal Cell, found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but who fully recovered.

His team found that reductions in serotonin were driven by low levels of circulating SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused persistent inflammation as well as an inability of the body to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactive blood platelets were also shown to play a role; they serve as the primary means of serotonin absorption.

The study doesn’t make any recommendations for treatment, but understanding the role of serotonin in long COVID opens the door to a host of novel ideas that could set the stage for clinical trials and affect care.

“The study gives us a few possible targets that could be used in future clinical studies,” Dr. Thaiss said.

Persistent circulating virus is one of the drivers of low serotonin levels, said study author Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. This points to the need to reduce viral load using antiviral medications like nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, and VV116, which has not yet been approved for use against COVID.

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the oral antiviral agent VV116 was as effective as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in reducing the body’s viral load and aiding recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Paxlovid has also been shown to reduce the likelihood of getting long COVID after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Researchers are investigating ways to target serotonin levels directly, potentially using SSRIs. But first they need to study whether improvement in serotonin level makes a difference.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said.

Indeed, the research did show that the SSRI fluoxetine, as well as a glycine-tryptophan supplement, improved cognitive function in SARS-CoV-2-infected rodent models, which were used in a portion of the study.

David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, said the research is helping “to paint a biological picture” that’s in line with other research on the mechanisms that cause long COVID symptoms.

But Dr. Putrino, who was not involved in the study, cautions against treating long COVID patients with SSRIs or any other treatment that increases serotonin before testing patients to determine whether their serotonin levels are actually lower than those of healthy persons.

“We don’t want to assume that every patient with long COVID is going to have lower serotonin levels,” said Dr. Putrino.

What’s more, researchers need to investigate whether SSRIs increase levels of circulating serotonin. It’s important to note that researchers found lower levels of circulating serotonin but that serotonin levels in the brain remained normal.

Traditionally, SSRIs are used clinically for increasing the levels of serotonin in the brain, not the body.

“Whether that’s going to contribute to an increase in systemic levels of serotonin, that’s something that needs to be tested,” said Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, co-lead investigator of the Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., COVID-19 Recovery Study, who was not involved in the research.

Thus far, investigators have not identified one unifying biomarker that seems to cause long COVID in all patients, said Dr. Iwasaki. Some research has found higher levels of certain immune cells and biomarkers: for example, monocytes and activated B lymphocytes, indicating a stronger and ongoing antibody response to the virus. Other recent research conducted by Dr. Iwasaki, Dr. Putrino, and others, published in the journal Nature, showed that long COVID patients tend to have lower levels of cortisol, which could be a factor in the extreme fatigue experienced by many who suffer from the condition.

The findings in the study in The Cell are promising, but they need to be replicated in more people, said Dr. Iwasaki. And even if they’re replicated in a larger study population, this would still be just one biomarker that is associated with one subtype of the disease. There is a need to better understand which biomarkers go with which symptoms so that the most effective treatments can be identified, she said.

Both Dr. Putrino and Dr. Iwasaki contended that there isn’t a single factor that can explain all of long COVID. It’s a complex disease caused by a host of different mechanisms.

Still, low levels of serotonin could be an important piece of the puzzle. The next step, said Dr. Iwasaki, is to uncover how many of the millions of Americans with long COVID have this biomarker.

“People working in the field of long COVID should now be considering this pathway and thinking of ways to measure serotonin in their patients.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could antidepressants hold the key to treating long COVID? The study even points to a possible treatment.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that has many functions in the body and is targeted by the most commonly prescribed antidepressants – the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Serotonin is widely studied for its effects on the brain – it regulates the messaging between neurons, affecting sleep, mood, and memory. It is present in the gut, is found in cells along the gastrointestinal tract, and is absorbed by blood platelets. Gut serotonin, known as circulating serotonin, is responsible for a host of other functions, including the regulation of blood flow, body temperature, and digestion.

Low levels of serotonin could result in any number of seemingly unrelated symptoms, as in the case of long COVID, experts say. The condition affects about 7% of Americans and is associated with a wide range of health problems, including fatigue, shortness of breath, neurological symptoms, joint pain, blood clots, heart palpitations, and digestive problems.

Long COVID is difficult to treat because researchers haven’t been able to pinpoint the underlying mechanisms that cause prolonged illness after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, said study author Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The hope is that this study could have implications for new treatments, he said.

“Long COVID can have manifestations not only in the brain but in many different parts of the body, so it’s possible that serotonin reductions are involved in many different aspects of the disease,” said Dr. Thaiss.

Dr. Thaiss’s study, published in the journal Cell, found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but who fully recovered.

His team found that reductions in serotonin were driven by low levels of circulating SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused persistent inflammation as well as an inability of the body to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactive blood platelets were also shown to play a role; they serve as the primary means of serotonin absorption.

The study doesn’t make any recommendations for treatment, but understanding the role of serotonin in long COVID opens the door to a host of novel ideas that could set the stage for clinical trials and affect care.

“The study gives us a few possible targets that could be used in future clinical studies,” Dr. Thaiss said.

Persistent circulating virus is one of the drivers of low serotonin levels, said study author Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. This points to the need to reduce viral load using antiviral medications like nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, and VV116, which has not yet been approved for use against COVID.

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the oral antiviral agent VV116 was as effective as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in reducing the body’s viral load and aiding recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Paxlovid has also been shown to reduce the likelihood of getting long COVID after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Researchers are investigating ways to target serotonin levels directly, potentially using SSRIs. But first they need to study whether improvement in serotonin level makes a difference.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said.

Indeed, the research did show that the SSRI fluoxetine, as well as a glycine-tryptophan supplement, improved cognitive function in SARS-CoV-2-infected rodent models, which were used in a portion of the study.

David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, said the research is helping “to paint a biological picture” that’s in line with other research on the mechanisms that cause long COVID symptoms.

But Dr. Putrino, who was not involved in the study, cautions against treating long COVID patients with SSRIs or any other treatment that increases serotonin before testing patients to determine whether their serotonin levels are actually lower than those of healthy persons.

“We don’t want to assume that every patient with long COVID is going to have lower serotonin levels,” said Dr. Putrino.

What’s more, researchers need to investigate whether SSRIs increase levels of circulating serotonin. It’s important to note that researchers found lower levels of circulating serotonin but that serotonin levels in the brain remained normal.

Traditionally, SSRIs are used clinically for increasing the levels of serotonin in the brain, not the body.

“Whether that’s going to contribute to an increase in systemic levels of serotonin, that’s something that needs to be tested,” said Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, co-lead investigator of the Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., COVID-19 Recovery Study, who was not involved in the research.

Thus far, investigators have not identified one unifying biomarker that seems to cause long COVID in all patients, said Dr. Iwasaki. Some research has found higher levels of certain immune cells and biomarkers: for example, monocytes and activated B lymphocytes, indicating a stronger and ongoing antibody response to the virus. Other recent research conducted by Dr. Iwasaki, Dr. Putrino, and others, published in the journal Nature, showed that long COVID patients tend to have lower levels of cortisol, which could be a factor in the extreme fatigue experienced by many who suffer from the condition.

The findings in the study in The Cell are promising, but they need to be replicated in more people, said Dr. Iwasaki. And even if they’re replicated in a larger study population, this would still be just one biomarker that is associated with one subtype of the disease. There is a need to better understand which biomarkers go with which symptoms so that the most effective treatments can be identified, she said.

Both Dr. Putrino and Dr. Iwasaki contended that there isn’t a single factor that can explain all of long COVID. It’s a complex disease caused by a host of different mechanisms.

Still, low levels of serotonin could be an important piece of the puzzle. The next step, said Dr. Iwasaki, is to uncover how many of the millions of Americans with long COVID have this biomarker.

“People working in the field of long COVID should now be considering this pathway and thinking of ways to measure serotonin in their patients.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could antidepressants hold the key to treating long COVID? The study even points to a possible treatment.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that has many functions in the body and is targeted by the most commonly prescribed antidepressants – the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Serotonin is widely studied for its effects on the brain – it regulates the messaging between neurons, affecting sleep, mood, and memory. It is present in the gut, is found in cells along the gastrointestinal tract, and is absorbed by blood platelets. Gut serotonin, known as circulating serotonin, is responsible for a host of other functions, including the regulation of blood flow, body temperature, and digestion.

Low levels of serotonin could result in any number of seemingly unrelated symptoms, as in the case of long COVID, experts say. The condition affects about 7% of Americans and is associated with a wide range of health problems, including fatigue, shortness of breath, neurological symptoms, joint pain, blood clots, heart palpitations, and digestive problems.

Long COVID is difficult to treat because researchers haven’t been able to pinpoint the underlying mechanisms that cause prolonged illness after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, said study author Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The hope is that this study could have implications for new treatments, he said.

“Long COVID can have manifestations not only in the brain but in many different parts of the body, so it’s possible that serotonin reductions are involved in many different aspects of the disease,” said Dr. Thaiss.

Dr. Thaiss’s study, published in the journal Cell, found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but who fully recovered.

His team found that reductions in serotonin were driven by low levels of circulating SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused persistent inflammation as well as an inability of the body to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactive blood platelets were also shown to play a role; they serve as the primary means of serotonin absorption.

The study doesn’t make any recommendations for treatment, but understanding the role of serotonin in long COVID opens the door to a host of novel ideas that could set the stage for clinical trials and affect care.

“The study gives us a few possible targets that could be used in future clinical studies,” Dr. Thaiss said.

Persistent circulating virus is one of the drivers of low serotonin levels, said study author Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. This points to the need to reduce viral load using antiviral medications like nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, and VV116, which has not yet been approved for use against COVID.

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the oral antiviral agent VV116 was as effective as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in reducing the body’s viral load and aiding recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Paxlovid has also been shown to reduce the likelihood of getting long COVID after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Researchers are investigating ways to target serotonin levels directly, potentially using SSRIs. But first they need to study whether improvement in serotonin level makes a difference.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said.

Indeed, the research did show that the SSRI fluoxetine, as well as a glycine-tryptophan supplement, improved cognitive function in SARS-CoV-2-infected rodent models, which were used in a portion of the study.

David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, said the research is helping “to paint a biological picture” that’s in line with other research on the mechanisms that cause long COVID symptoms.

But Dr. Putrino, who was not involved in the study, cautions against treating long COVID patients with SSRIs or any other treatment that increases serotonin before testing patients to determine whether their serotonin levels are actually lower than those of healthy persons.

“We don’t want to assume that every patient with long COVID is going to have lower serotonin levels,” said Dr. Putrino.

What’s more, researchers need to investigate whether SSRIs increase levels of circulating serotonin. It’s important to note that researchers found lower levels of circulating serotonin but that serotonin levels in the brain remained normal.

Traditionally, SSRIs are used clinically for increasing the levels of serotonin in the brain, not the body.

“Whether that’s going to contribute to an increase in systemic levels of serotonin, that’s something that needs to be tested,” said Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, co-lead investigator of the Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., COVID-19 Recovery Study, who was not involved in the research.

Thus far, investigators have not identified one unifying biomarker that seems to cause long COVID in all patients, said Dr. Iwasaki. Some research has found higher levels of certain immune cells and biomarkers: for example, monocytes and activated B lymphocytes, indicating a stronger and ongoing antibody response to the virus. Other recent research conducted by Dr. Iwasaki, Dr. Putrino, and others, published in the journal Nature, showed that long COVID patients tend to have lower levels of cortisol, which could be a factor in the extreme fatigue experienced by many who suffer from the condition.

The findings in the study in The Cell are promising, but they need to be replicated in more people, said Dr. Iwasaki. And even if they’re replicated in a larger study population, this would still be just one biomarker that is associated with one subtype of the disease. There is a need to better understand which biomarkers go with which symptoms so that the most effective treatments can be identified, she said.