User login

Wuhan virus: What clinicians need to know

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

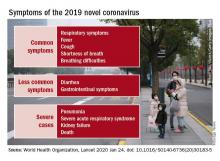

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

If patients exhibit symptoms and either they or a close contact has returned from China recently, take standard airborne precautions and send specimens – a serum sample, oral and nasal pharyngeal swabs, and lower respiratory tract specimens if available – to the local health department, which will forward them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing. Turnaround time is 24-48 hours.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in December in association with a live animal market in Wuhan, China, has been implicated in almost 2,000 cases and 56 deaths in that country. Cases have been reported in 13 countries besides China. Five cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been confirmed in the United States, all in people recently returned from Wuhan. As the virus spreads in China, however, it’s almost certain more cases will show up in the United States. Travel history is key, Dr. Schaffner and others said.

Plan and rehearse

The first step to prepare is to use the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals to make a written plan specific to your practice to respond to a potential case. The plan must include notifying the local health department, the CDC liaison for testing, and tracking down patient contacts.

“It’s not good enough to just download CDC’s guidance; use it to make your own local plan and know what to do 24/7,” said Daniel Lucey, MD, an infectious disease expert at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

“Know who is on call at the health department on weekends and nights,” he said. Know where the patient is going to be isolated; figure out what to do if there’s more than one, and tests come back positive. Have masks on hand, and rehearse the response. “Make a coronavirus team, and absolutely have the nurses involved,” as well as other providers who may come into contact with a case, he added.

“You want to be able to do as well as your counterparts in Washington state and Chicago,” where the first two U.S. cases emerged. “They were prepared. They knew what to do,” Dr. Lucey said.

Those first two U.S. patients – a man in Everett, Wash., and a Chicago woman – developed symptoms after returning from Wuhan, a city of 11 million just over 400 miles inland from the port city of Shanghai. On Jan. 26 three more cases were confirmed by the CDC, two in California and one in Arizona, and each had recently traveled to Wuhan. All five patients remain hospitalized, and there’s no evidence they spread the infection further. There is also no evidence of human-to-human transmission of other cases exported from China to any other countries, according to the WHO.

WHO declined to declare a global health emergency – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in its parlance – on Jan. 23. The step would have triggered travel and trade restrictions in member states, including the United States. For now, at least, the group said it wasn’t warranted at this point.

Fatality rates

The focus right now is China. The outbreak has spread beyond Wuhan to other parts of the country, and there’s evidence of fourth-generation spread.

Transportation into and out of Wuhan and other cities has been curtailed, Lunar New Year festivals have been canceled, and the Shanghai Disneyland has been closed, among other measures taken by Chinese officials.

The government could be taking drastic measures in part to prevent the public criticism it took in the early 2000’s for the delayed response and lack of transparency during the global outbreak of another wildlife market coronavirus epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a press conference Jan. 22, WHO officials commended the government’s containment efforts but did not say they recommended them.

According to WHO, serious cases in China have mostly been in people over 40 years old with significant comorbidities and have skewed towards men. Spread seems to be limited to family members, health care providers, and other close contacts, probably by respiratory droplets. If that pattern holds, WHO officials said, the outbreak is containable.

The fatality rate appears to be around 3%, a good deal lower than the 10% reported for SARS and much lower than the nearly 40% reported for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another recent coronavirus mutation from the animal trade.

The Wuhan virus fatality rate might drop as milder cases are detected and added to the denominator. “It definitely appears to be less severe than SARS and MERS,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease physician in Pittsburgh and emerging infectious disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

SARS: Lessons learned

In general, the world is much better equipped for coronavirus outbreaks than when SARS, in particular, emerged in 2003.

WHO officials in their press conference lauded China for it openness with the current outbreak, and for isolating and sequencing the virus immediately, which gave the world a diagnostic test in the first days of the outbreak, something that wasn’t available for SARS. China and other countries also are cooperating and working closely to contain the Wuhan virus.

“What we know today might change tomorrow, so we have to keep tuned in to new information, but we learned a lot from SARS,” Dr. Shaffner said. Overall, it’s likely “the impact on the United States of this new coronavirus is going to be trivial,” he predicted.

Dr. Lucey, however, recalled that the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003 started with one missed case. A woman returned asymptomatic from Hong Kong and spread the infection to her family members before she died. Her cause of death wasn’t immediately recognized, nor was the reason her family members were sick, since they hadn’t been to Hong Kong recently.

The infection ultimately spread to more than 200 people, about half of them health care workers. A few people died.

If a virus is sufficiently contagious, “it just takes one. You don’t want to be the one who misses that first patient,” Dr. Lucey said.

Currently, there are no antivirals or vaccines for coronaviruses; researchers are working on both, but for now, care is supportive.

This article was updated with new case numbers on 1/26/20.

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

If patients exhibit symptoms and either they or a close contact has returned from China recently, take standard airborne precautions and send specimens – a serum sample, oral and nasal pharyngeal swabs, and lower respiratory tract specimens if available – to the local health department, which will forward them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing. Turnaround time is 24-48 hours.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in December in association with a live animal market in Wuhan, China, has been implicated in almost 2,000 cases and 56 deaths in that country. Cases have been reported in 13 countries besides China. Five cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been confirmed in the United States, all in people recently returned from Wuhan. As the virus spreads in China, however, it’s almost certain more cases will show up in the United States. Travel history is key, Dr. Schaffner and others said.

Plan and rehearse

The first step to prepare is to use the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals to make a written plan specific to your practice to respond to a potential case. The plan must include notifying the local health department, the CDC liaison for testing, and tracking down patient contacts.

“It’s not good enough to just download CDC’s guidance; use it to make your own local plan and know what to do 24/7,” said Daniel Lucey, MD, an infectious disease expert at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

“Know who is on call at the health department on weekends and nights,” he said. Know where the patient is going to be isolated; figure out what to do if there’s more than one, and tests come back positive. Have masks on hand, and rehearse the response. “Make a coronavirus team, and absolutely have the nurses involved,” as well as other providers who may come into contact with a case, he added.

“You want to be able to do as well as your counterparts in Washington state and Chicago,” where the first two U.S. cases emerged. “They were prepared. They knew what to do,” Dr. Lucey said.

Those first two U.S. patients – a man in Everett, Wash., and a Chicago woman – developed symptoms after returning from Wuhan, a city of 11 million just over 400 miles inland from the port city of Shanghai. On Jan. 26 three more cases were confirmed by the CDC, two in California and one in Arizona, and each had recently traveled to Wuhan. All five patients remain hospitalized, and there’s no evidence they spread the infection further. There is also no evidence of human-to-human transmission of other cases exported from China to any other countries, according to the WHO.

WHO declined to declare a global health emergency – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in its parlance – on Jan. 23. The step would have triggered travel and trade restrictions in member states, including the United States. For now, at least, the group said it wasn’t warranted at this point.

Fatality rates

The focus right now is China. The outbreak has spread beyond Wuhan to other parts of the country, and there’s evidence of fourth-generation spread.

Transportation into and out of Wuhan and other cities has been curtailed, Lunar New Year festivals have been canceled, and the Shanghai Disneyland has been closed, among other measures taken by Chinese officials.

The government could be taking drastic measures in part to prevent the public criticism it took in the early 2000’s for the delayed response and lack of transparency during the global outbreak of another wildlife market coronavirus epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a press conference Jan. 22, WHO officials commended the government’s containment efforts but did not say they recommended them.

According to WHO, serious cases in China have mostly been in people over 40 years old with significant comorbidities and have skewed towards men. Spread seems to be limited to family members, health care providers, and other close contacts, probably by respiratory droplets. If that pattern holds, WHO officials said, the outbreak is containable.

The fatality rate appears to be around 3%, a good deal lower than the 10% reported for SARS and much lower than the nearly 40% reported for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another recent coronavirus mutation from the animal trade.

The Wuhan virus fatality rate might drop as milder cases are detected and added to the denominator. “It definitely appears to be less severe than SARS and MERS,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease physician in Pittsburgh and emerging infectious disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

SARS: Lessons learned

In general, the world is much better equipped for coronavirus outbreaks than when SARS, in particular, emerged in 2003.

WHO officials in their press conference lauded China for it openness with the current outbreak, and for isolating and sequencing the virus immediately, which gave the world a diagnostic test in the first days of the outbreak, something that wasn’t available for SARS. China and other countries also are cooperating and working closely to contain the Wuhan virus.

“What we know today might change tomorrow, so we have to keep tuned in to new information, but we learned a lot from SARS,” Dr. Shaffner said. Overall, it’s likely “the impact on the United States of this new coronavirus is going to be trivial,” he predicted.

Dr. Lucey, however, recalled that the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003 started with one missed case. A woman returned asymptomatic from Hong Kong and spread the infection to her family members before she died. Her cause of death wasn’t immediately recognized, nor was the reason her family members were sick, since they hadn’t been to Hong Kong recently.

The infection ultimately spread to more than 200 people, about half of them health care workers. A few people died.

If a virus is sufficiently contagious, “it just takes one. You don’t want to be the one who misses that first patient,” Dr. Lucey said.

Currently, there are no antivirals or vaccines for coronaviruses; researchers are working on both, but for now, care is supportive.

This article was updated with new case numbers on 1/26/20.

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

If patients exhibit symptoms and either they or a close contact has returned from China recently, take standard airborne precautions and send specimens – a serum sample, oral and nasal pharyngeal swabs, and lower respiratory tract specimens if available – to the local health department, which will forward them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing. Turnaround time is 24-48 hours.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in December in association with a live animal market in Wuhan, China, has been implicated in almost 2,000 cases and 56 deaths in that country. Cases have been reported in 13 countries besides China. Five cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been confirmed in the United States, all in people recently returned from Wuhan. As the virus spreads in China, however, it’s almost certain more cases will show up in the United States. Travel history is key, Dr. Schaffner and others said.

Plan and rehearse

The first step to prepare is to use the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals to make a written plan specific to your practice to respond to a potential case. The plan must include notifying the local health department, the CDC liaison for testing, and tracking down patient contacts.

“It’s not good enough to just download CDC’s guidance; use it to make your own local plan and know what to do 24/7,” said Daniel Lucey, MD, an infectious disease expert at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

“Know who is on call at the health department on weekends and nights,” he said. Know where the patient is going to be isolated; figure out what to do if there’s more than one, and tests come back positive. Have masks on hand, and rehearse the response. “Make a coronavirus team, and absolutely have the nurses involved,” as well as other providers who may come into contact with a case, he added.

“You want to be able to do as well as your counterparts in Washington state and Chicago,” where the first two U.S. cases emerged. “They were prepared. They knew what to do,” Dr. Lucey said.

Those first two U.S. patients – a man in Everett, Wash., and a Chicago woman – developed symptoms after returning from Wuhan, a city of 11 million just over 400 miles inland from the port city of Shanghai. On Jan. 26 three more cases were confirmed by the CDC, two in California and one in Arizona, and each had recently traveled to Wuhan. All five patients remain hospitalized, and there’s no evidence they spread the infection further. There is also no evidence of human-to-human transmission of other cases exported from China to any other countries, according to the WHO.

WHO declined to declare a global health emergency – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in its parlance – on Jan. 23. The step would have triggered travel and trade restrictions in member states, including the United States. For now, at least, the group said it wasn’t warranted at this point.

Fatality rates

The focus right now is China. The outbreak has spread beyond Wuhan to other parts of the country, and there’s evidence of fourth-generation spread.

Transportation into and out of Wuhan and other cities has been curtailed, Lunar New Year festivals have been canceled, and the Shanghai Disneyland has been closed, among other measures taken by Chinese officials.

The government could be taking drastic measures in part to prevent the public criticism it took in the early 2000’s for the delayed response and lack of transparency during the global outbreak of another wildlife market coronavirus epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a press conference Jan. 22, WHO officials commended the government’s containment efforts but did not say they recommended them.

According to WHO, serious cases in China have mostly been in people over 40 years old with significant comorbidities and have skewed towards men. Spread seems to be limited to family members, health care providers, and other close contacts, probably by respiratory droplets. If that pattern holds, WHO officials said, the outbreak is containable.

The fatality rate appears to be around 3%, a good deal lower than the 10% reported for SARS and much lower than the nearly 40% reported for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another recent coronavirus mutation from the animal trade.

The Wuhan virus fatality rate might drop as milder cases are detected and added to the denominator. “It definitely appears to be less severe than SARS and MERS,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease physician in Pittsburgh and emerging infectious disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

SARS: Lessons learned

In general, the world is much better equipped for coronavirus outbreaks than when SARS, in particular, emerged in 2003.

WHO officials in their press conference lauded China for it openness with the current outbreak, and for isolating and sequencing the virus immediately, which gave the world a diagnostic test in the first days of the outbreak, something that wasn’t available for SARS. China and other countries also are cooperating and working closely to contain the Wuhan virus.

“What we know today might change tomorrow, so we have to keep tuned in to new information, but we learned a lot from SARS,” Dr. Shaffner said. Overall, it’s likely “the impact on the United States of this new coronavirus is going to be trivial,” he predicted.

Dr. Lucey, however, recalled that the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003 started with one missed case. A woman returned asymptomatic from Hong Kong and spread the infection to her family members before she died. Her cause of death wasn’t immediately recognized, nor was the reason her family members were sick, since they hadn’t been to Hong Kong recently.

The infection ultimately spread to more than 200 people, about half of them health care workers. A few people died.

If a virus is sufficiently contagious, “it just takes one. You don’t want to be the one who misses that first patient,” Dr. Lucey said.

Currently, there are no antivirals or vaccines for coronaviruses; researchers are working on both, but for now, care is supportive.

This article was updated with new case numbers on 1/26/20.

Exogenous boosting against shingles not as robust as thought

Exposure to children with chickenpox reduces the incidence of shingles in adults 33% over 2 years, and 27% out to 20 years, according to British investigators.

Being exposed to children with illness due to varicella infection acts as an “exogenous booster” in adults who had chickenpox themselves as children, making shingles less likely, they explained in a BMJ article.

Although that’s good news, it’s been reported previously that exposure to children with chickenpox confers complete protection against shingles in adults for years afterward.

The finding matters in the United Kingdom because varicella vaccine is not part of the pediatric immunization schedule. The United States is the only country that mandates two shots as a requirement for children to attend school.

The United Kingdom, however, is reconsidering its policy. In the past, the exogenous booster idea has been one of the arguments used against mandating the vaccine for children; the concern is that preventing chickenpox in children – and subsequent reexposure to herpes zoster in adults – would kick off a costly wave of shingles in adults.

The study results “are themselves unable to justify for or against specific vaccination schedules, but they do suggest that revised mathematical models are required to estimate the impact of varicella vaccination, with the updated assumption that exogenous boosting is incomplete and only reduces the risk of zoster by about 30%,” noted the investigators, led by Harriet Forbes of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The researchers identified 9,604 adults with a shingles diagnosis during 1997-2018 who at some point lived with a child who had chickenpox. Data came from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink, a general practice database.

They then looked at the incidence of shingles within 20 years of exposure to the sick child and compared it with the incidence before exposure and after 20 years, by which time the exogenous booster is thought to wear off. It was a self-controlled case series analysis, “a relatively novel epidemiological study design where individuals act as their own controls. Comparisons are made within individuals rather than between individuals as in a cohort or case control study,” Ms. Forbes and colleagues explained.

After adjustment for age, calendar time, and season, they found that in the 2 years after household exposure to a child with varicella, adults were 33% less likely to develop zoster (incidence ratio 0.67, 95% confidence interval 0.62-0.73), and 27% less likely from 10 to 20 years (IR 0.73, CI 0.62-0.87). The boosting effect appeared to be stronger in men.

“Exogenous boosting provides some protection from the risk of herpes zoster, but not complete immunity, as assumed by previous cost effectiveness estimates of varicella immunization,” the researchers said.

More than two-thirds of the adults with shingles were women, which fits with previous reports. Median age of exposure to a child with varicella was 38 years.

Ms. Forbes and colleagues noted that “the study design required patients with zoster to be living with a child with varicella, therefore the study cohort is younger than a general population with zoster. ... However, when we restricted our analysis to adults aged 50 and older at exposure to varicella, a similar pattern of association was observed, with no evidence of effect modification by age. This suggests that although the median age of our study cohort ... was low, the findings can be generalized to older people.”

There was no external funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no relevant financial disclosures. One investigator reported research grants from GSK and Merck, both makers of chickenpox and shingles vaccines.

SOURCE: Forbes H et al. BMJ. 2020 Jan 22;368:l6987.

Exposure to children with chickenpox reduces the incidence of shingles in adults 33% over 2 years, and 27% out to 20 years, according to British investigators.

Being exposed to children with illness due to varicella infection acts as an “exogenous booster” in adults who had chickenpox themselves as children, making shingles less likely, they explained in a BMJ article.

Although that’s good news, it’s been reported previously that exposure to children with chickenpox confers complete protection against shingles in adults for years afterward.

The finding matters in the United Kingdom because varicella vaccine is not part of the pediatric immunization schedule. The United States is the only country that mandates two shots as a requirement for children to attend school.

The United Kingdom, however, is reconsidering its policy. In the past, the exogenous booster idea has been one of the arguments used against mandating the vaccine for children; the concern is that preventing chickenpox in children – and subsequent reexposure to herpes zoster in adults – would kick off a costly wave of shingles in adults.

The study results “are themselves unable to justify for or against specific vaccination schedules, but they do suggest that revised mathematical models are required to estimate the impact of varicella vaccination, with the updated assumption that exogenous boosting is incomplete and only reduces the risk of zoster by about 30%,” noted the investigators, led by Harriet Forbes of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The researchers identified 9,604 adults with a shingles diagnosis during 1997-2018 who at some point lived with a child who had chickenpox. Data came from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink, a general practice database.

They then looked at the incidence of shingles within 20 years of exposure to the sick child and compared it with the incidence before exposure and after 20 years, by which time the exogenous booster is thought to wear off. It was a self-controlled case series analysis, “a relatively novel epidemiological study design where individuals act as their own controls. Comparisons are made within individuals rather than between individuals as in a cohort or case control study,” Ms. Forbes and colleagues explained.

After adjustment for age, calendar time, and season, they found that in the 2 years after household exposure to a child with varicella, adults were 33% less likely to develop zoster (incidence ratio 0.67, 95% confidence interval 0.62-0.73), and 27% less likely from 10 to 20 years (IR 0.73, CI 0.62-0.87). The boosting effect appeared to be stronger in men.

“Exogenous boosting provides some protection from the risk of herpes zoster, but not complete immunity, as assumed by previous cost effectiveness estimates of varicella immunization,” the researchers said.

More than two-thirds of the adults with shingles were women, which fits with previous reports. Median age of exposure to a child with varicella was 38 years.

Ms. Forbes and colleagues noted that “the study design required patients with zoster to be living with a child with varicella, therefore the study cohort is younger than a general population with zoster. ... However, when we restricted our analysis to adults aged 50 and older at exposure to varicella, a similar pattern of association was observed, with no evidence of effect modification by age. This suggests that although the median age of our study cohort ... was low, the findings can be generalized to older people.”

There was no external funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no relevant financial disclosures. One investigator reported research grants from GSK and Merck, both makers of chickenpox and shingles vaccines.

SOURCE: Forbes H et al. BMJ. 2020 Jan 22;368:l6987.

Exposure to children with chickenpox reduces the incidence of shingles in adults 33% over 2 years, and 27% out to 20 years, according to British investigators.

Being exposed to children with illness due to varicella infection acts as an “exogenous booster” in adults who had chickenpox themselves as children, making shingles less likely, they explained in a BMJ article.

Although that’s good news, it’s been reported previously that exposure to children with chickenpox confers complete protection against shingles in adults for years afterward.

The finding matters in the United Kingdom because varicella vaccine is not part of the pediatric immunization schedule. The United States is the only country that mandates two shots as a requirement for children to attend school.

The United Kingdom, however, is reconsidering its policy. In the past, the exogenous booster idea has been one of the arguments used against mandating the vaccine for children; the concern is that preventing chickenpox in children – and subsequent reexposure to herpes zoster in adults – would kick off a costly wave of shingles in adults.

The study results “are themselves unable to justify for or against specific vaccination schedules, but they do suggest that revised mathematical models are required to estimate the impact of varicella vaccination, with the updated assumption that exogenous boosting is incomplete and only reduces the risk of zoster by about 30%,” noted the investigators, led by Harriet Forbes of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The researchers identified 9,604 adults with a shingles diagnosis during 1997-2018 who at some point lived with a child who had chickenpox. Data came from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink, a general practice database.

They then looked at the incidence of shingles within 20 years of exposure to the sick child and compared it with the incidence before exposure and after 20 years, by which time the exogenous booster is thought to wear off. It was a self-controlled case series analysis, “a relatively novel epidemiological study design where individuals act as their own controls. Comparisons are made within individuals rather than between individuals as in a cohort or case control study,” Ms. Forbes and colleagues explained.

After adjustment for age, calendar time, and season, they found that in the 2 years after household exposure to a child with varicella, adults were 33% less likely to develop zoster (incidence ratio 0.67, 95% confidence interval 0.62-0.73), and 27% less likely from 10 to 20 years (IR 0.73, CI 0.62-0.87). The boosting effect appeared to be stronger in men.

“Exogenous boosting provides some protection from the risk of herpes zoster, but not complete immunity, as assumed by previous cost effectiveness estimates of varicella immunization,” the researchers said.

More than two-thirds of the adults with shingles were women, which fits with previous reports. Median age of exposure to a child with varicella was 38 years.

Ms. Forbes and colleagues noted that “the study design required patients with zoster to be living with a child with varicella, therefore the study cohort is younger than a general population with zoster. ... However, when we restricted our analysis to adults aged 50 and older at exposure to varicella, a similar pattern of association was observed, with no evidence of effect modification by age. This suggests that although the median age of our study cohort ... was low, the findings can be generalized to older people.”

There was no external funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no relevant financial disclosures. One investigator reported research grants from GSK and Merck, both makers of chickenpox and shingles vaccines.

SOURCE: Forbes H et al. BMJ. 2020 Jan 22;368:l6987.

FROM BMJ

Can we eradicate malaria by 2050?

A new report by members of the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication has called for ending malaria in Africa within a generation, specifically aiming at the year 2050.

The Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication is a joint endeavor between The Lancet and the University of California, San Francisco, and was convened in 2017 to consider the feasibility and affordability of malaria eradication, as well as to identify priority actions for the achievement of the goal. Eradication was considered “a necessary one given the never-ending struggle against drug and insecticide resistance and the social and economic costs associated with a failure to eradicate.”

Between 2000 and 2017, the worldwide annual incidence of malaria declined by 36%, and the annual death rate declined by 60%, according to the report. In 2007, Bill and Melinda Gates proposed that controlling malaria was not enough and complete eradication was the only scientifically and ethically defensible objective. This goal was adopted by the World Health Organization and other interested parties, and by 2015, global strategies and a potential timeline for eradication were developed.

“Global progress has stalled since 2015 and the malaria community is now at a critical moment, faced with a decision to either temper its ambitions as it did in 1969 or recommit to an eradication goal,” according to the report.

In the report, the authors used new modeling analysis to estimate plausible scenarios for the distribution and intensity of malaria in 2030 and 2050. Socioeconomic and environmental trends, together with enhanced access to high-quality diagnosis, treatment, and vector control, could lead to a “world largely free of malaria” by 2050, but with pockets of low-level transmission persisting across a belt of Africa.

Current statistics lend weight to the promise of eventual eradication, according to the report.

Between 2000 and 2017, 20 countries – constituting about one-fifth of the 106 malaria-endemic countries in 2000 – eliminated malaria transmission within their borders, reporting zero indigenous malaria cases for at least 1 year. However, this was counterbalanced by the fact that between 2015 and 2017, 55 countries had an increase in cases, and 38 countries had an increase in deaths.

“The good news is that 38 countries had incidences of fewer than ten cases per 1,000 population in 2017, with 25 countries reporting fewer than one case per 1,000 population. The same 38 countries reported just 5% of total malaria deaths. Nearly all of these low-burden countries are actively working towards national and regional elimination goals of 2030 or earlier,” according to the report.

The analysis undertaken for the report consisted of the following four steps:

1. Development of a machine-learning model to capture associations between malaria endemicity data and a wide range of socioeconomic and environmental geospatial covariates.

2. Mapping of covariate estimates to the years 2030 and 2050 on the basis of projected global trends.

3. Application of the associations learned in the first step to projected covariates generated in the second step to estimate the possible future global landscape of malaria endemicity.

4. Use of a mathematical transmission model to explore the potential effect of differing levels of malaria interventions.

The report indicates that an annual spending of $6 billion or more is required, while the current global expenditure is approximately $4.3 billion. An additional investment of $2 billion per year is necessary, with a quarter of the funds coming from increased development assistance from external donors and the rest from government health spending in malaria-endemic countries, according to the report.

However, other areas of concern remain, including the current lack of effective and widely deployable outdoor biting technologies, though these are expected to be available within the next decade, according to the report.

In terms of the modeling used in the report, the authors noted that past performance does not “capture the effect of mass drug administration or mass chemoprevention because these interventions are either relatively new or have yet to be applied widely. These underestimates might be counteracted by the absence of drug or insecticide resistance from our projections,which result in overly optimistic estimates for the continued efficacy of current tools.”

The commission was launched in October 2017 by the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco. The commission built on the 2010 Lancet Malaria Elimination Series, “which evaluated the operational, technical, and financial requirements for malaria elimination and helped shape and build early support for the eradication agenda,” according to the report.

SOURCE: Feachem RGA et al. Lancet. 2019 Sept 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0.

A new report by members of the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication has called for ending malaria in Africa within a generation, specifically aiming at the year 2050.

The Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication is a joint endeavor between The Lancet and the University of California, San Francisco, and was convened in 2017 to consider the feasibility and affordability of malaria eradication, as well as to identify priority actions for the achievement of the goal. Eradication was considered “a necessary one given the never-ending struggle against drug and insecticide resistance and the social and economic costs associated with a failure to eradicate.”

Between 2000 and 2017, the worldwide annual incidence of malaria declined by 36%, and the annual death rate declined by 60%, according to the report. In 2007, Bill and Melinda Gates proposed that controlling malaria was not enough and complete eradication was the only scientifically and ethically defensible objective. This goal was adopted by the World Health Organization and other interested parties, and by 2015, global strategies and a potential timeline for eradication were developed.

“Global progress has stalled since 2015 and the malaria community is now at a critical moment, faced with a decision to either temper its ambitions as it did in 1969 or recommit to an eradication goal,” according to the report.

In the report, the authors used new modeling analysis to estimate plausible scenarios for the distribution and intensity of malaria in 2030 and 2050. Socioeconomic and environmental trends, together with enhanced access to high-quality diagnosis, treatment, and vector control, could lead to a “world largely free of malaria” by 2050, but with pockets of low-level transmission persisting across a belt of Africa.

Current statistics lend weight to the promise of eventual eradication, according to the report.

Between 2000 and 2017, 20 countries – constituting about one-fifth of the 106 malaria-endemic countries in 2000 – eliminated malaria transmission within their borders, reporting zero indigenous malaria cases for at least 1 year. However, this was counterbalanced by the fact that between 2015 and 2017, 55 countries had an increase in cases, and 38 countries had an increase in deaths.

“The good news is that 38 countries had incidences of fewer than ten cases per 1,000 population in 2017, with 25 countries reporting fewer than one case per 1,000 population. The same 38 countries reported just 5% of total malaria deaths. Nearly all of these low-burden countries are actively working towards national and regional elimination goals of 2030 or earlier,” according to the report.

The analysis undertaken for the report consisted of the following four steps:

1. Development of a machine-learning model to capture associations between malaria endemicity data and a wide range of socioeconomic and environmental geospatial covariates.

2. Mapping of covariate estimates to the years 2030 and 2050 on the basis of projected global trends.

3. Application of the associations learned in the first step to projected covariates generated in the second step to estimate the possible future global landscape of malaria endemicity.

4. Use of a mathematical transmission model to explore the potential effect of differing levels of malaria interventions.

The report indicates that an annual spending of $6 billion or more is required, while the current global expenditure is approximately $4.3 billion. An additional investment of $2 billion per year is necessary, with a quarter of the funds coming from increased development assistance from external donors and the rest from government health spending in malaria-endemic countries, according to the report.

However, other areas of concern remain, including the current lack of effective and widely deployable outdoor biting technologies, though these are expected to be available within the next decade, according to the report.

In terms of the modeling used in the report, the authors noted that past performance does not “capture the effect of mass drug administration or mass chemoprevention because these interventions are either relatively new or have yet to be applied widely. These underestimates might be counteracted by the absence of drug or insecticide resistance from our projections,which result in overly optimistic estimates for the continued efficacy of current tools.”

The commission was launched in October 2017 by the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco. The commission built on the 2010 Lancet Malaria Elimination Series, “which evaluated the operational, technical, and financial requirements for malaria elimination and helped shape and build early support for the eradication agenda,” according to the report.

SOURCE: Feachem RGA et al. Lancet. 2019 Sept 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0.

A new report by members of the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication has called for ending malaria in Africa within a generation, specifically aiming at the year 2050.

The Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication is a joint endeavor between The Lancet and the University of California, San Francisco, and was convened in 2017 to consider the feasibility and affordability of malaria eradication, as well as to identify priority actions for the achievement of the goal. Eradication was considered “a necessary one given the never-ending struggle against drug and insecticide resistance and the social and economic costs associated with a failure to eradicate.”

Between 2000 and 2017, the worldwide annual incidence of malaria declined by 36%, and the annual death rate declined by 60%, according to the report. In 2007, Bill and Melinda Gates proposed that controlling malaria was not enough and complete eradication was the only scientifically and ethically defensible objective. This goal was adopted by the World Health Organization and other interested parties, and by 2015, global strategies and a potential timeline for eradication were developed.

“Global progress has stalled since 2015 and the malaria community is now at a critical moment, faced with a decision to either temper its ambitions as it did in 1969 or recommit to an eradication goal,” according to the report.

In the report, the authors used new modeling analysis to estimate plausible scenarios for the distribution and intensity of malaria in 2030 and 2050. Socioeconomic and environmental trends, together with enhanced access to high-quality diagnosis, treatment, and vector control, could lead to a “world largely free of malaria” by 2050, but with pockets of low-level transmission persisting across a belt of Africa.

Current statistics lend weight to the promise of eventual eradication, according to the report.

Between 2000 and 2017, 20 countries – constituting about one-fifth of the 106 malaria-endemic countries in 2000 – eliminated malaria transmission within their borders, reporting zero indigenous malaria cases for at least 1 year. However, this was counterbalanced by the fact that between 2015 and 2017, 55 countries had an increase in cases, and 38 countries had an increase in deaths.

“The good news is that 38 countries had incidences of fewer than ten cases per 1,000 population in 2017, with 25 countries reporting fewer than one case per 1,000 population. The same 38 countries reported just 5% of total malaria deaths. Nearly all of these low-burden countries are actively working towards national and regional elimination goals of 2030 or earlier,” according to the report.

The analysis undertaken for the report consisted of the following four steps:

1. Development of a machine-learning model to capture associations between malaria endemicity data and a wide range of socioeconomic and environmental geospatial covariates.

2. Mapping of covariate estimates to the years 2030 and 2050 on the basis of projected global trends.

3. Application of the associations learned in the first step to projected covariates generated in the second step to estimate the possible future global landscape of malaria endemicity.

4. Use of a mathematical transmission model to explore the potential effect of differing levels of malaria interventions.

The report indicates that an annual spending of $6 billion or more is required, while the current global expenditure is approximately $4.3 billion. An additional investment of $2 billion per year is necessary, with a quarter of the funds coming from increased development assistance from external donors and the rest from government health spending in malaria-endemic countries, according to the report.

However, other areas of concern remain, including the current lack of effective and widely deployable outdoor biting technologies, though these are expected to be available within the next decade, according to the report.

In terms of the modeling used in the report, the authors noted that past performance does not “capture the effect of mass drug administration or mass chemoprevention because these interventions are either relatively new or have yet to be applied widely. These underestimates might be counteracted by the absence of drug or insecticide resistance from our projections,which result in overly optimistic estimates for the continued efficacy of current tools.”

The commission was launched in October 2017 by the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco. The commission built on the 2010 Lancet Malaria Elimination Series, “which evaluated the operational, technical, and financial requirements for malaria elimination and helped shape and build early support for the eradication agenda,” according to the report.

SOURCE: Feachem RGA et al. Lancet. 2019 Sept 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0.

FROM THE LANCET

Post-Ebola mortality five times higher than general population

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Renal failure was the assumed cause of death in 63% of the survivors based on reported anuria.

Major finding:

Study details: A postdischarge survey of 1,130 (89%) of the Ebola survivors and their relations in Guinea.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Scabies rates plummeted with community mass drug administration

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD2019

CDC activates Emergency Operations Center for Congo Ebola outbreak

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.