User login

Can TEE find septal defects in conotruncal repair?

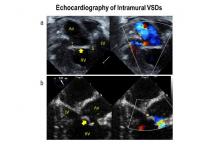

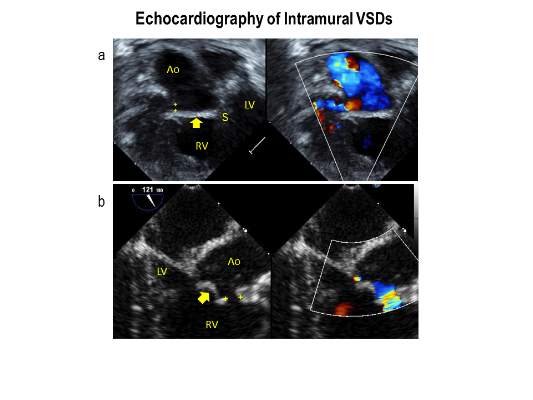

Intramural ventricular septal defects (VSD), residual defects that can occur after repair of conotruncal defects in newborns, increase the risk of complications and death if they’re not detected and closed during the index operation. While various methods have been tried to find these defects during surgery, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) reported that the use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has a good chance of finding VSDs and giving cardiac surgeons the opportunity to correct these residual defects.

“TEE has modest sensitivity but high specificity for identifying intramural VSDs and can identify most defects requiring reinterventions,” Jyoti Patel, MD, and her coauthors reported in a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:688-95).

Previous studies have shown that intraoperative TEE is safe for evaluating operations in congenital heart disease, but this is the first study to evaluate the modality for detecting intramural VSDs, Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Dr. Patel and her coinvestigators analyzed results of TEE and postoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) in patients who had biventricular repair of conotruncal anomalies at CHOP from January 2006 through June 2013. Intramural VSDs occurred in 34 of 337 patients who met the inclusion criteria out of a total population of 903. Actually, 462 patients had biventricular repairs of conotruncal defects involving baffle closure of a VSD, but 125 were excluded for various reasons, including 105 for inadequate intraoperative TEE.

TTE identified a total of 177 residual VSDs, 34 of which were intramural in nature. Among the evaluated procedures, both TEE at the end of the index operation and TTE detected VSD in 19 patients; TTE alone found VSD in 15. “Sensitivity was 56% and specificity was 100% for TEE to identify intramural VSDs,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

What’s more, both TTE and TEE combined identified peripatch VSDs in 90 patients, while TTE only in 53 and TEE only in 15, “yielding a sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 92%,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Of the VSDs that required catheterization or reintervention during surgery, intraoperative TEE detected six of seven intramural VSDs and all five peripatch VSDs, the study found.

“In this study, TEE identified most intramural VSDs and all peripatch VSDs that required subsequent reintervention,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

“This finding underscores the importance of adequate imaging of the superior aspect of the VSD patch during intraoperative TEE for conotruncal anomalies, given that many intramural defects may be repaired during the initial operation.”

Coauthor Andrew Glatz, MD, disclosed receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and coauthor Chitra Ravishankar, MD, disclosed lecture fees from Danone Medical. Dr. Patel and the remaining coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Because of the clinical importance of intramural VSDs, cardiac surgeons need to be highly suspicious in any operation to repair conotruncal defects where the VSD margins are close to the trabeculae, Edward Buratto, MBBS, Philip Naimo, MD, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, of Royal Children’s Hospital at the University of Melbourne said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:696-7). “The best way to resolve the problem would be to prevent it,” they said.

While intraoperative TEE can detect VSDs preemptively, the imaging technique is “not without its flaws,” the commentators said, as evidenced by the 105 subjects the CHOP study excluded because of inadequate TEE imaging. Those excluded cases comprised patients aged 30 days and younger with lower body weight and higher early death rates. “It is these patients who would benefit most from intraoperative identification of intramural VSD,” the commentators said.

They also noted that TEE in detecting intramural and peripatch VSD in children aged 30 days and older “was not perfect either,” with sensitivities of 56% and 63%, respectively. In the CHOP study, TEE was more likely to detect intramural VSD in patients older than 30 days with higher body weight, Dr. Buratto and his colleagues said.

The favored approach at Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne is routine epicardial echocardiograms in conotruncal repair. This imaging technique provides “superb imaging quality,” they said. “This is of particular importance in small children.” They advocate closing a significant VSD once it’s identified.

“After all, failure to close intramural VSD occurs when surgeons do not realize how close they were to success when they gave up,” the commentators said. Precise echocardiographic guidance would “dramatically facilitate” that strategy.

Dr. Buratto, Dr. Naimo, and Dr. Konstantinov had no financial relationships to disclose.

Because of the clinical importance of intramural VSDs, cardiac surgeons need to be highly suspicious in any operation to repair conotruncal defects where the VSD margins are close to the trabeculae, Edward Buratto, MBBS, Philip Naimo, MD, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, of Royal Children’s Hospital at the University of Melbourne said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:696-7). “The best way to resolve the problem would be to prevent it,” they said.

While intraoperative TEE can detect VSDs preemptively, the imaging technique is “not without its flaws,” the commentators said, as evidenced by the 105 subjects the CHOP study excluded because of inadequate TEE imaging. Those excluded cases comprised patients aged 30 days and younger with lower body weight and higher early death rates. “It is these patients who would benefit most from intraoperative identification of intramural VSD,” the commentators said.

They also noted that TEE in detecting intramural and peripatch VSD in children aged 30 days and older “was not perfect either,” with sensitivities of 56% and 63%, respectively. In the CHOP study, TEE was more likely to detect intramural VSD in patients older than 30 days with higher body weight, Dr. Buratto and his colleagues said.

The favored approach at Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne is routine epicardial echocardiograms in conotruncal repair. This imaging technique provides “superb imaging quality,” they said. “This is of particular importance in small children.” They advocate closing a significant VSD once it’s identified.

“After all, failure to close intramural VSD occurs when surgeons do not realize how close they were to success when they gave up,” the commentators said. Precise echocardiographic guidance would “dramatically facilitate” that strategy.

Dr. Buratto, Dr. Naimo, and Dr. Konstantinov had no financial relationships to disclose.

Because of the clinical importance of intramural VSDs, cardiac surgeons need to be highly suspicious in any operation to repair conotruncal defects where the VSD margins are close to the trabeculae, Edward Buratto, MBBS, Philip Naimo, MD, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, of Royal Children’s Hospital at the University of Melbourne said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:696-7). “The best way to resolve the problem would be to prevent it,” they said.

While intraoperative TEE can detect VSDs preemptively, the imaging technique is “not without its flaws,” the commentators said, as evidenced by the 105 subjects the CHOP study excluded because of inadequate TEE imaging. Those excluded cases comprised patients aged 30 days and younger with lower body weight and higher early death rates. “It is these patients who would benefit most from intraoperative identification of intramural VSD,” the commentators said.

They also noted that TEE in detecting intramural and peripatch VSD in children aged 30 days and older “was not perfect either,” with sensitivities of 56% and 63%, respectively. In the CHOP study, TEE was more likely to detect intramural VSD in patients older than 30 days with higher body weight, Dr. Buratto and his colleagues said.

The favored approach at Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne is routine epicardial echocardiograms in conotruncal repair. This imaging technique provides “superb imaging quality,” they said. “This is of particular importance in small children.” They advocate closing a significant VSD once it’s identified.

“After all, failure to close intramural VSD occurs when surgeons do not realize how close they were to success when they gave up,” the commentators said. Precise echocardiographic guidance would “dramatically facilitate” that strategy.

Dr. Buratto, Dr. Naimo, and Dr. Konstantinov had no financial relationships to disclose.

Intramural ventricular septal defects (VSD), residual defects that can occur after repair of conotruncal defects in newborns, increase the risk of complications and death if they’re not detected and closed during the index operation. While various methods have been tried to find these defects during surgery, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) reported that the use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has a good chance of finding VSDs and giving cardiac surgeons the opportunity to correct these residual defects.

“TEE has modest sensitivity but high specificity for identifying intramural VSDs and can identify most defects requiring reinterventions,” Jyoti Patel, MD, and her coauthors reported in a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:688-95).

Previous studies have shown that intraoperative TEE is safe for evaluating operations in congenital heart disease, but this is the first study to evaluate the modality for detecting intramural VSDs, Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Dr. Patel and her coinvestigators analyzed results of TEE and postoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) in patients who had biventricular repair of conotruncal anomalies at CHOP from January 2006 through June 2013. Intramural VSDs occurred in 34 of 337 patients who met the inclusion criteria out of a total population of 903. Actually, 462 patients had biventricular repairs of conotruncal defects involving baffle closure of a VSD, but 125 were excluded for various reasons, including 105 for inadequate intraoperative TEE.

TTE identified a total of 177 residual VSDs, 34 of which were intramural in nature. Among the evaluated procedures, both TEE at the end of the index operation and TTE detected VSD in 19 patients; TTE alone found VSD in 15. “Sensitivity was 56% and specificity was 100% for TEE to identify intramural VSDs,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

What’s more, both TTE and TEE combined identified peripatch VSDs in 90 patients, while TTE only in 53 and TEE only in 15, “yielding a sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 92%,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Of the VSDs that required catheterization or reintervention during surgery, intraoperative TEE detected six of seven intramural VSDs and all five peripatch VSDs, the study found.

“In this study, TEE identified most intramural VSDs and all peripatch VSDs that required subsequent reintervention,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

“This finding underscores the importance of adequate imaging of the superior aspect of the VSD patch during intraoperative TEE for conotruncal anomalies, given that many intramural defects may be repaired during the initial operation.”

Coauthor Andrew Glatz, MD, disclosed receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and coauthor Chitra Ravishankar, MD, disclosed lecture fees from Danone Medical. Dr. Patel and the remaining coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Intramural ventricular septal defects (VSD), residual defects that can occur after repair of conotruncal defects in newborns, increase the risk of complications and death if they’re not detected and closed during the index operation. While various methods have been tried to find these defects during surgery, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) reported that the use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has a good chance of finding VSDs and giving cardiac surgeons the opportunity to correct these residual defects.

“TEE has modest sensitivity but high specificity for identifying intramural VSDs and can identify most defects requiring reinterventions,” Jyoti Patel, MD, and her coauthors reported in a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:688-95).

Previous studies have shown that intraoperative TEE is safe for evaluating operations in congenital heart disease, but this is the first study to evaluate the modality for detecting intramural VSDs, Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Dr. Patel and her coinvestigators analyzed results of TEE and postoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) in patients who had biventricular repair of conotruncal anomalies at CHOP from January 2006 through June 2013. Intramural VSDs occurred in 34 of 337 patients who met the inclusion criteria out of a total population of 903. Actually, 462 patients had biventricular repairs of conotruncal defects involving baffle closure of a VSD, but 125 were excluded for various reasons, including 105 for inadequate intraoperative TEE.

TTE identified a total of 177 residual VSDs, 34 of which were intramural in nature. Among the evaluated procedures, both TEE at the end of the index operation and TTE detected VSD in 19 patients; TTE alone found VSD in 15. “Sensitivity was 56% and specificity was 100% for TEE to identify intramural VSDs,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

What’s more, both TTE and TEE combined identified peripatch VSDs in 90 patients, while TTE only in 53 and TEE only in 15, “yielding a sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 92%,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

Of the VSDs that required catheterization or reintervention during surgery, intraoperative TEE detected six of seven intramural VSDs and all five peripatch VSDs, the study found.

“In this study, TEE identified most intramural VSDs and all peripatch VSDs that required subsequent reintervention,” Dr. Patel and her colleagues said.

“This finding underscores the importance of adequate imaging of the superior aspect of the VSD patch during intraoperative TEE for conotruncal anomalies, given that many intramural defects may be repaired during the initial operation.”

Coauthor Andrew Glatz, MD, disclosed receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and coauthor Chitra Ravishankar, MD, disclosed lecture fees from Danone Medical. Dr. Patel and the remaining coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography has modest sensitivity but high specificity for detecting ventricular septal defects after repair of conotruncal anomalies.

Major finding: TEE is useful for identifying most VSDs during the index operation, providing the opportunity to repair the defects during the index operation.

Data source: A single-institution database of 337 patients who had operations to repair conotruncal anomalies between January 2006 and June 2013.

Disclosures: Coauthor Andrew Glatz, MD, disclosed receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and coauthor Chitra Ravishankar, MD, disclosed lecture fees from Danone Medical. Dr. Patel and the remaining coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Inadequate diversity snags hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genetic linkages

The genetic tests used for more than a decade to identify patients or family members who carry genetic mutations linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are seriously flawed.

The tests have been erroneously flagging people as genetically positive for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) when they actually carried benign genetic variants, according to a new reassessment of the genetic linkages by researchers using a more genetically diverse database. Five genetic variants now reclassified as benign were collectively responsible for flagging 74% of people flagged at genetic risk for HC in the more than 8,500 cases examined.

The results call into question any genetic diagnosis of HC made since genetic testing entered the mainstream in 2003, especially among African Americans who seem to have been disproportionately affected by these mislabeled genetic markers because of inadequate population diversity when the markers were first established.

In addition, the results more broadly cast a shadow over the full spectrum of genetic tests for disease-linked variants now in routine medical practice because of the possibility that other linkage determinations derived from an inadequately-representative reference population, reported Arjun K. Manrai, PhD, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 18;375[7]:655-65). The researchers call the HC experience they document a “cautionary tale of broad relevance to genetic diagnosis.”

The findings “powerfully illustrate the importance of racial and genetic diversity” when running linkage studies aimed at validating genetic markers for widespread clinical use, Isaac S. Kohane, MD, senior author of the study, said in a written statement. “Racial and ethnic inclusiveness improves the validity and accuracy” of genetic tests, said Dr. Kohane, professor of biomedical informatics and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“We believe that what we’re seeing in the case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may be the tip of the iceberg of a larger problem that transcends a single genetic disease,” Dr. Manrai, a biomedical informatics researcher at Harvard, said in the same statement. “Much genetic assessment today relies on historical links between a disorder and variant, sometimes decades old. We believe our findings illustrate the critical need to systematically reevaluate prior assertions about genetic variants,” Dr. Manrai added in an interview.

The two researchers and their associates reexamined the link between genetic variants and HC in three genetic databases that involved a total of more than 8,500 people. One database included 4,300 white Americans and 2,203 black Americans. A second database included genetic data from 1,092 people from 14 worldwide populations, and the third had genetic data from 938 people from 51 worldwide populations.

The analysis showed that although 94 distinct genetic variants that had previously been reported as associated with HC were confirmed as linked, just 5 met the study’s definition of a “high-frequency” variant with an allele frequent of more than 1%. These five variants together accounted for 74% of the overall total of linkages seen in these 8,533 people. Further analysis classified all five of these high-frequency genetic variants as benign with no discernible link to HC.

These five high-frequency variants occurred disproportionately higher among black Americans, and the consequences of this showed up in the patient records the researchers reviewed from one large U.S. genetic testing laboratory. They examined in detail HC genetic test results during 2004-2013 from 2,912 unrelated people. The records showed seven people had been labeled as carrying either a pathogenic or “presumed pathogenic” variant when in fact they had one of the five high-frequency variants now declared benign. Five of the seven mislabeled people were of African ancestry; the other two had unknown ancestry.

The researchers called for reevaluating known variants for all genetic diseases in more diverse populations and to immediately release the results of updated linkage assessments. This has the potential to meaningfully rewrite current gospel for many genetic variants and linkages.

“Our findings point to the value of patients staying in contact with their genetic counselors and physicians, even years after genetic testing,” Dr. Manrai said. Reassessments using more diverse populations will take time, he acknowledged, but tools are available to allow clinical geneticists to update old variants and apply new ones in real time, as soon as a new assessment completes.

Dr. Manrai and Dr. Kohane had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The genetic tests used for more than a decade to identify patients or family members who carry genetic mutations linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are seriously flawed.

The tests have been erroneously flagging people as genetically positive for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) when they actually carried benign genetic variants, according to a new reassessment of the genetic linkages by researchers using a more genetically diverse database. Five genetic variants now reclassified as benign were collectively responsible for flagging 74% of people flagged at genetic risk for HC in the more than 8,500 cases examined.

The results call into question any genetic diagnosis of HC made since genetic testing entered the mainstream in 2003, especially among African Americans who seem to have been disproportionately affected by these mislabeled genetic markers because of inadequate population diversity when the markers were first established.

In addition, the results more broadly cast a shadow over the full spectrum of genetic tests for disease-linked variants now in routine medical practice because of the possibility that other linkage determinations derived from an inadequately-representative reference population, reported Arjun K. Manrai, PhD, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 18;375[7]:655-65). The researchers call the HC experience they document a “cautionary tale of broad relevance to genetic diagnosis.”

The findings “powerfully illustrate the importance of racial and genetic diversity” when running linkage studies aimed at validating genetic markers for widespread clinical use, Isaac S. Kohane, MD, senior author of the study, said in a written statement. “Racial and ethnic inclusiveness improves the validity and accuracy” of genetic tests, said Dr. Kohane, professor of biomedical informatics and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“We believe that what we’re seeing in the case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may be the tip of the iceberg of a larger problem that transcends a single genetic disease,” Dr. Manrai, a biomedical informatics researcher at Harvard, said in the same statement. “Much genetic assessment today relies on historical links between a disorder and variant, sometimes decades old. We believe our findings illustrate the critical need to systematically reevaluate prior assertions about genetic variants,” Dr. Manrai added in an interview.

The two researchers and their associates reexamined the link between genetic variants and HC in three genetic databases that involved a total of more than 8,500 people. One database included 4,300 white Americans and 2,203 black Americans. A second database included genetic data from 1,092 people from 14 worldwide populations, and the third had genetic data from 938 people from 51 worldwide populations.

The analysis showed that although 94 distinct genetic variants that had previously been reported as associated with HC were confirmed as linked, just 5 met the study’s definition of a “high-frequency” variant with an allele frequent of more than 1%. These five variants together accounted for 74% of the overall total of linkages seen in these 8,533 people. Further analysis classified all five of these high-frequency genetic variants as benign with no discernible link to HC.

These five high-frequency variants occurred disproportionately higher among black Americans, and the consequences of this showed up in the patient records the researchers reviewed from one large U.S. genetic testing laboratory. They examined in detail HC genetic test results during 2004-2013 from 2,912 unrelated people. The records showed seven people had been labeled as carrying either a pathogenic or “presumed pathogenic” variant when in fact they had one of the five high-frequency variants now declared benign. Five of the seven mislabeled people were of African ancestry; the other two had unknown ancestry.

The researchers called for reevaluating known variants for all genetic diseases in more diverse populations and to immediately release the results of updated linkage assessments. This has the potential to meaningfully rewrite current gospel for many genetic variants and linkages.

“Our findings point to the value of patients staying in contact with their genetic counselors and physicians, even years after genetic testing,” Dr. Manrai said. Reassessments using more diverse populations will take time, he acknowledged, but tools are available to allow clinical geneticists to update old variants and apply new ones in real time, as soon as a new assessment completes.

Dr. Manrai and Dr. Kohane had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The genetic tests used for more than a decade to identify patients or family members who carry genetic mutations linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are seriously flawed.

The tests have been erroneously flagging people as genetically positive for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) when they actually carried benign genetic variants, according to a new reassessment of the genetic linkages by researchers using a more genetically diverse database. Five genetic variants now reclassified as benign were collectively responsible for flagging 74% of people flagged at genetic risk for HC in the more than 8,500 cases examined.

The results call into question any genetic diagnosis of HC made since genetic testing entered the mainstream in 2003, especially among African Americans who seem to have been disproportionately affected by these mislabeled genetic markers because of inadequate population diversity when the markers were first established.

In addition, the results more broadly cast a shadow over the full spectrum of genetic tests for disease-linked variants now in routine medical practice because of the possibility that other linkage determinations derived from an inadequately-representative reference population, reported Arjun K. Manrai, PhD, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 18;375[7]:655-65). The researchers call the HC experience they document a “cautionary tale of broad relevance to genetic diagnosis.”

The findings “powerfully illustrate the importance of racial and genetic diversity” when running linkage studies aimed at validating genetic markers for widespread clinical use, Isaac S. Kohane, MD, senior author of the study, said in a written statement. “Racial and ethnic inclusiveness improves the validity and accuracy” of genetic tests, said Dr. Kohane, professor of biomedical informatics and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“We believe that what we’re seeing in the case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may be the tip of the iceberg of a larger problem that transcends a single genetic disease,” Dr. Manrai, a biomedical informatics researcher at Harvard, said in the same statement. “Much genetic assessment today relies on historical links between a disorder and variant, sometimes decades old. We believe our findings illustrate the critical need to systematically reevaluate prior assertions about genetic variants,” Dr. Manrai added in an interview.

The two researchers and their associates reexamined the link between genetic variants and HC in three genetic databases that involved a total of more than 8,500 people. One database included 4,300 white Americans and 2,203 black Americans. A second database included genetic data from 1,092 people from 14 worldwide populations, and the third had genetic data from 938 people from 51 worldwide populations.

The analysis showed that although 94 distinct genetic variants that had previously been reported as associated with HC were confirmed as linked, just 5 met the study’s definition of a “high-frequency” variant with an allele frequent of more than 1%. These five variants together accounted for 74% of the overall total of linkages seen in these 8,533 people. Further analysis classified all five of these high-frequency genetic variants as benign with no discernible link to HC.

These five high-frequency variants occurred disproportionately higher among black Americans, and the consequences of this showed up in the patient records the researchers reviewed from one large U.S. genetic testing laboratory. They examined in detail HC genetic test results during 2004-2013 from 2,912 unrelated people. The records showed seven people had been labeled as carrying either a pathogenic or “presumed pathogenic” variant when in fact they had one of the five high-frequency variants now declared benign. Five of the seven mislabeled people were of African ancestry; the other two had unknown ancestry.

The researchers called for reevaluating known variants for all genetic diseases in more diverse populations and to immediately release the results of updated linkage assessments. This has the potential to meaningfully rewrite current gospel for many genetic variants and linkages.

“Our findings point to the value of patients staying in contact with their genetic counselors and physicians, even years after genetic testing,” Dr. Manrai said. Reassessments using more diverse populations will take time, he acknowledged, but tools are available to allow clinical geneticists to update old variants and apply new ones in real time, as soon as a new assessment completes.

Dr. Manrai and Dr. Kohane had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Key clinical point: Five high-frequency genetic variants that collectively had been linked to 74% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cases are actually benign with no detectable pathologic linkage.

Major finding: Inaccurate linkage data mislabeled seven people as having a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy–causing genetic variant.

Data source: Three genomic sequence databases that included 8,533 people and a genetic laboratory’s records for 2,912 clients.

Disclosures: Dr. Manrai and Dr. Kohane had no disclosures.

Can anesthesia in infants affect IQ scores?

About 10,000 newborns receive general anesthesia for congenital heart defects every year, and the more exposure they have to inhaled anesthetic agents, the greater effect it may have on their neurologic development, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported in a study of newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

While previous studies have linked worse neurodevelopment to patient factors like prematurity and genetics, this is the first study to show a consistent relationship between neurodevelopment outcomes and modifiable factors during cardiac surgery in infants, Laura K. Diaz, MD, and her colleagues reported in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:482-9).

They studied 96 patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) or similar syndromes who received volatile anesthetic agents (VAA) at their institution from 1998 to 2003. The patients underwent a battery of neurodevelopmental tests between the ages of 4 and 5 years that included full-scale IQ (FSIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and processing speed.

“This study provides evidence that in children undergoing staged reconstructive surgery for HLHS, increasing cumulative exposure to VAAs beginning in infancy is associated with worse performance for FSIQ and VIQ, suggesting that VAA exposure may be a modifiable risk factor for adverse neurodevelopment outcomes,” Dr. Diaz and her colleagues wrote.

While survival has improved significantly in recent years for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, physicians have harbored concerns that these children encounter neurodevelopmental issues later on. Dr. Diaz and her colleagues acknowledged that previous studies have shown factors, such as the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and hospital length of stay, that could affect neurodevelopment in these children, but the findings have been inconsistent. Instead, those studies have shown such patient-specific factors as birth weight, ethnicity, and hereditary disorders were strong determinants of neurodevelopment in infants who have cardiac surgery, Dr. Diaz and her coauthors pointed out.

Their own previous study of patients with single-ventricle congenital heart disease concurred with the findings of those other studies, but it did not evaluate exposure to anesthesia (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014;147:1276-82). That was the focus of their current study.

Among the study group, 94 patients had an initial operation with CPB in their first 30 days of life. All 96 infants in the study group had additional operations, whether cardiac or noncardiac. The study tracked all anesthetic exposures up until the neurodevelopment evaluation in February 2008. All but 2 patients had initial VAA exposure at less than 1 year of age, and 45 at less than 1 month of age. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used uniformly for aortic arch reconstruction.

The study used four different generalized linear models to evaluate anesthesia exposure and neurodevelopment.

For both FSIQ and PIQ, total minimum alveolar concentration hours were deemed to be statistically significant factors for lower scores. For PIQ, birth weight and length of postoperative hospital stay were statistically significant. For processing speed, gestational age and length of hospital stay were statistically significant.

Dr. Diaz and her colleagues said their findings are preliminary and do not justify a change in practice. “Prospective randomized, controlled multicenter clinical trials are indicated to continue to clarify the effects of early and repetitive exposure to VAA in this and other pediatric populations,” the study authors concluded.

Dr. Diaz and the study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Diaz and her colleagues makes all the more clear the need for a prospective randomized trial on the effect inhaled anesthetic agents in infants can have on their neurologic development, Richard A. Jonas, MD, of Children’s National Heart Institute, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;152:490).

|

Dr. Richard A. Jonas |

However, besides the study limitations that Dr. Diaz and her colleagues pointed out in their study, another “problem” Dr. Jonas noted with the study subjects was that they had staged reconstruction for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. “Not only is this group of patients at risk for prenatal effects of their abnormal in utero circulation, but in addition, they all underwent additional cardiac or noncardiac procedures after their initial cardiac surgery,” he said. These factors, along with some degree of cyanosis in their formative years, may help explain why this study is an outlier in that it did not implicate nonoperative factors that other studies implicated, Dr. Jonas said.

Nonetheless, the study is “an important contribution that adds further evidence to the observation that volatile agents can affect neurodevelopmental outcome,” Dr. Jonas said. Hence the need for a prospective randomized trial.

Dr. Jonas had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Diaz and her colleagues makes all the more clear the need for a prospective randomized trial on the effect inhaled anesthetic agents in infants can have on their neurologic development, Richard A. Jonas, MD, of Children’s National Heart Institute, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;152:490).

|

Dr. Richard A. Jonas |

However, besides the study limitations that Dr. Diaz and her colleagues pointed out in their study, another “problem” Dr. Jonas noted with the study subjects was that they had staged reconstruction for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. “Not only is this group of patients at risk for prenatal effects of their abnormal in utero circulation, but in addition, they all underwent additional cardiac or noncardiac procedures after their initial cardiac surgery,” he said. These factors, along with some degree of cyanosis in their formative years, may help explain why this study is an outlier in that it did not implicate nonoperative factors that other studies implicated, Dr. Jonas said.

Nonetheless, the study is “an important contribution that adds further evidence to the observation that volatile agents can affect neurodevelopmental outcome,” Dr. Jonas said. Hence the need for a prospective randomized trial.

Dr. Jonas had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Diaz and her colleagues makes all the more clear the need for a prospective randomized trial on the effect inhaled anesthetic agents in infants can have on their neurologic development, Richard A. Jonas, MD, of Children’s National Heart Institute, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;152:490).

|

Dr. Richard A. Jonas |

However, besides the study limitations that Dr. Diaz and her colleagues pointed out in their study, another “problem” Dr. Jonas noted with the study subjects was that they had staged reconstruction for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. “Not only is this group of patients at risk for prenatal effects of their abnormal in utero circulation, but in addition, they all underwent additional cardiac or noncardiac procedures after their initial cardiac surgery,” he said. These factors, along with some degree of cyanosis in their formative years, may help explain why this study is an outlier in that it did not implicate nonoperative factors that other studies implicated, Dr. Jonas said.

Nonetheless, the study is “an important contribution that adds further evidence to the observation that volatile agents can affect neurodevelopmental outcome,” Dr. Jonas said. Hence the need for a prospective randomized trial.

Dr. Jonas had no financial relationships to disclose.

About 10,000 newborns receive general anesthesia for congenital heart defects every year, and the more exposure they have to inhaled anesthetic agents, the greater effect it may have on their neurologic development, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported in a study of newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

While previous studies have linked worse neurodevelopment to patient factors like prematurity and genetics, this is the first study to show a consistent relationship between neurodevelopment outcomes and modifiable factors during cardiac surgery in infants, Laura K. Diaz, MD, and her colleagues reported in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:482-9).

They studied 96 patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) or similar syndromes who received volatile anesthetic agents (VAA) at their institution from 1998 to 2003. The patients underwent a battery of neurodevelopmental tests between the ages of 4 and 5 years that included full-scale IQ (FSIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and processing speed.

“This study provides evidence that in children undergoing staged reconstructive surgery for HLHS, increasing cumulative exposure to VAAs beginning in infancy is associated with worse performance for FSIQ and VIQ, suggesting that VAA exposure may be a modifiable risk factor for adverse neurodevelopment outcomes,” Dr. Diaz and her colleagues wrote.

While survival has improved significantly in recent years for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, physicians have harbored concerns that these children encounter neurodevelopmental issues later on. Dr. Diaz and her colleagues acknowledged that previous studies have shown factors, such as the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and hospital length of stay, that could affect neurodevelopment in these children, but the findings have been inconsistent. Instead, those studies have shown such patient-specific factors as birth weight, ethnicity, and hereditary disorders were strong determinants of neurodevelopment in infants who have cardiac surgery, Dr. Diaz and her coauthors pointed out.

Their own previous study of patients with single-ventricle congenital heart disease concurred with the findings of those other studies, but it did not evaluate exposure to anesthesia (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014;147:1276-82). That was the focus of their current study.

Among the study group, 94 patients had an initial operation with CPB in their first 30 days of life. All 96 infants in the study group had additional operations, whether cardiac or noncardiac. The study tracked all anesthetic exposures up until the neurodevelopment evaluation in February 2008. All but 2 patients had initial VAA exposure at less than 1 year of age, and 45 at less than 1 month of age. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used uniformly for aortic arch reconstruction.

The study used four different generalized linear models to evaluate anesthesia exposure and neurodevelopment.

For both FSIQ and PIQ, total minimum alveolar concentration hours were deemed to be statistically significant factors for lower scores. For PIQ, birth weight and length of postoperative hospital stay were statistically significant. For processing speed, gestational age and length of hospital stay were statistically significant.

Dr. Diaz and her colleagues said their findings are preliminary and do not justify a change in practice. “Prospective randomized, controlled multicenter clinical trials are indicated to continue to clarify the effects of early and repetitive exposure to VAA in this and other pediatric populations,” the study authors concluded.

Dr. Diaz and the study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

About 10,000 newborns receive general anesthesia for congenital heart defects every year, and the more exposure they have to inhaled anesthetic agents, the greater effect it may have on their neurologic development, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported in a study of newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

While previous studies have linked worse neurodevelopment to patient factors like prematurity and genetics, this is the first study to show a consistent relationship between neurodevelopment outcomes and modifiable factors during cardiac surgery in infants, Laura K. Diaz, MD, and her colleagues reported in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:482-9).

They studied 96 patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) or similar syndromes who received volatile anesthetic agents (VAA) at their institution from 1998 to 2003. The patients underwent a battery of neurodevelopmental tests between the ages of 4 and 5 years that included full-scale IQ (FSIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and processing speed.

“This study provides evidence that in children undergoing staged reconstructive surgery for HLHS, increasing cumulative exposure to VAAs beginning in infancy is associated with worse performance for FSIQ and VIQ, suggesting that VAA exposure may be a modifiable risk factor for adverse neurodevelopment outcomes,” Dr. Diaz and her colleagues wrote.

While survival has improved significantly in recent years for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, physicians have harbored concerns that these children encounter neurodevelopmental issues later on. Dr. Diaz and her colleagues acknowledged that previous studies have shown factors, such as the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and hospital length of stay, that could affect neurodevelopment in these children, but the findings have been inconsistent. Instead, those studies have shown such patient-specific factors as birth weight, ethnicity, and hereditary disorders were strong determinants of neurodevelopment in infants who have cardiac surgery, Dr. Diaz and her coauthors pointed out.

Their own previous study of patients with single-ventricle congenital heart disease concurred with the findings of those other studies, but it did not evaluate exposure to anesthesia (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014;147:1276-82). That was the focus of their current study.

Among the study group, 94 patients had an initial operation with CPB in their first 30 days of life. All 96 infants in the study group had additional operations, whether cardiac or noncardiac. The study tracked all anesthetic exposures up until the neurodevelopment evaluation in February 2008. All but 2 patients had initial VAA exposure at less than 1 year of age, and 45 at less than 1 month of age. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used uniformly for aortic arch reconstruction.

The study used four different generalized linear models to evaluate anesthesia exposure and neurodevelopment.

For both FSIQ and PIQ, total minimum alveolar concentration hours were deemed to be statistically significant factors for lower scores. For PIQ, birth weight and length of postoperative hospital stay were statistically significant. For processing speed, gestational age and length of hospital stay were statistically significant.

Dr. Diaz and her colleagues said their findings are preliminary and do not justify a change in practice. “Prospective randomized, controlled multicenter clinical trials are indicated to continue to clarify the effects of early and repetitive exposure to VAA in this and other pediatric populations,” the study authors concluded.

Dr. Diaz and the study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Volatile inhaled anesthesia may affect neurodevelopment in infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Major finding: Different generalized linear models determined an association between minimum alveolar concentration hours and hospital length of stay with lower IQ scores and processing speed.

Data source: Meta-analysis reviewed a subgroup of 96 patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome who had neurodevelopmental testing at a single center between 1998 and 2003.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Anatomic repair of ccTGA did not yield superior survival

BALTIMORE – Anatomic repair did not outperform physiologic repair in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA), according to a study presented by Maryam Al-Omair, M.D., of the University of Toronto at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Al-Omair and her colleagues hypothesized that patients undergoing anatomic repair for ccTGA would have superior systemic ventricular function and survival. However, their results showed that anatomic repair of ccTGA did not yield superior survival, compared with physiologic repair, and the long-term impact on systemic ventricular function was not certain.

Because of early evidence showing better outcomes of anatomic over physiologic repair for ccTGA, the surgical trend over time greatly favored the use of anatomic repair: At her team’s institution, anatomic repair went from 2.3% in the 1982-1989 period to 92.3% in the 2010-2015 period, Dr. Al-Omair said.

Their study assessed 200 patients (165 with biventricular ccTGA and 35 Fontan patients) who were managed from 1982 to 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The patient treatment groups were anatomic repair (38 patients), physiologic repair (89), single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (35), and palliated (no intracardiac repair) patients (38). The median follow-up was 3.4 years for anatomic repair, 13.5 years for physiologic repair, 7.5 years for single-ventricle repair, and 11.8 years with no repair (11.8 years), reflecting their change in practice.

The investigators followed the primary outcome of transplant-free survival and secondary outcomes of late systemic ventricular function and systemic atrioventricular valve function.

They found no significant difference in transplant-free survival at 20 years in the three repair groups assessed from 1892 to 2105: anatomic repair (58%), physiologic repair (71%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (78%). Looking at the latter period of 2000-2015 for 10-year transplant-free survival, they found similar results: anatomic repair (77%), physiologic repair (85%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (100%).

They also found that transplant-free survival in patients who required no intracadiac repair and had no associated lesions such as ventral septal defect or ventral septal defect with pulmonary stenosis was nearly 95% at 25 years.

A multivariate analysis showed no independent predictors of mortality among the three treatments, patient age at index operation, or period of treatment, as well as the need for a permanent pacemaker, or moderately to severely reduced ventricular function or moderate to severe valve regurgitation after the index operation, according to Dr. Al-Omair.

For the secondary outcome of late systemic ventricular function, a multivariate analysis showed that two of the variables were independent predictors: Index operation at or after 2000 was shown to be protective (hazard ratio, 0.152), while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced ventricular function after the index operation (HR, 12.4).

For the secondary outcome of late systemic valve function, a multivariate analysis showed that three of the variables were independent predictors: Fontan operation (HR, 0.124) and index operation at or after 2000 (HR, 0.258) were shown to be protective, while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced valve regurgitation after the index operation (HR, 9.00).

The researchers concluded that midterm Fontan survival was relatively favorable, pushing borderline repair may not be necessary, and “prophylactic banding” and the double-switch procedure should be looked on with caution for lower-risk patients.

“Our study also showed that survival was best in those having no associated lesions requiring operation, indicating that performing an anatomic repair for those not having associated lesions could be counterproductive,” Dr. Al-Omair concluded.

The webcast of the annual meeting presentation is available at www.aats.org.

Dr. Al-Omair reported that she and her colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

The choice of anatomic vs. physiologic repair of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries is a controversial area, with many well-known surgeons and centers advocating for anatomic repair (a much tougher and more challenging operation) as opposed to physiologic repair. The Toronto group is to be applauded for this honest conclusion, which goes a bit against the currently fashionable “more is better” approach.

Robert Jaquiss, M.D., of Duke University, Durham, N.C., is the congenital heart disease associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

The choice of anatomic vs. physiologic repair of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries is a controversial area, with many well-known surgeons and centers advocating for anatomic repair (a much tougher and more challenging operation) as opposed to physiologic repair. The Toronto group is to be applauded for this honest conclusion, which goes a bit against the currently fashionable “more is better” approach.

Robert Jaquiss, M.D., of Duke University, Durham, N.C., is the congenital heart disease associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

The choice of anatomic vs. physiologic repair of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries is a controversial area, with many well-known surgeons and centers advocating for anatomic repair (a much tougher and more challenging operation) as opposed to physiologic repair. The Toronto group is to be applauded for this honest conclusion, which goes a bit against the currently fashionable “more is better” approach.

Robert Jaquiss, M.D., of Duke University, Durham, N.C., is the congenital heart disease associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

BALTIMORE – Anatomic repair did not outperform physiologic repair in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA), according to a study presented by Maryam Al-Omair, M.D., of the University of Toronto at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Al-Omair and her colleagues hypothesized that patients undergoing anatomic repair for ccTGA would have superior systemic ventricular function and survival. However, their results showed that anatomic repair of ccTGA did not yield superior survival, compared with physiologic repair, and the long-term impact on systemic ventricular function was not certain.

Because of early evidence showing better outcomes of anatomic over physiologic repair for ccTGA, the surgical trend over time greatly favored the use of anatomic repair: At her team’s institution, anatomic repair went from 2.3% in the 1982-1989 period to 92.3% in the 2010-2015 period, Dr. Al-Omair said.

Their study assessed 200 patients (165 with biventricular ccTGA and 35 Fontan patients) who were managed from 1982 to 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The patient treatment groups were anatomic repair (38 patients), physiologic repair (89), single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (35), and palliated (no intracardiac repair) patients (38). The median follow-up was 3.4 years for anatomic repair, 13.5 years for physiologic repair, 7.5 years for single-ventricle repair, and 11.8 years with no repair (11.8 years), reflecting their change in practice.

The investigators followed the primary outcome of transplant-free survival and secondary outcomes of late systemic ventricular function and systemic atrioventricular valve function.

They found no significant difference in transplant-free survival at 20 years in the three repair groups assessed from 1892 to 2105: anatomic repair (58%), physiologic repair (71%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (78%). Looking at the latter period of 2000-2015 for 10-year transplant-free survival, they found similar results: anatomic repair (77%), physiologic repair (85%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (100%).

They also found that transplant-free survival in patients who required no intracadiac repair and had no associated lesions such as ventral septal defect or ventral septal defect with pulmonary stenosis was nearly 95% at 25 years.

A multivariate analysis showed no independent predictors of mortality among the three treatments, patient age at index operation, or period of treatment, as well as the need for a permanent pacemaker, or moderately to severely reduced ventricular function or moderate to severe valve regurgitation after the index operation, according to Dr. Al-Omair.

For the secondary outcome of late systemic ventricular function, a multivariate analysis showed that two of the variables were independent predictors: Index operation at or after 2000 was shown to be protective (hazard ratio, 0.152), while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced ventricular function after the index operation (HR, 12.4).

For the secondary outcome of late systemic valve function, a multivariate analysis showed that three of the variables were independent predictors: Fontan operation (HR, 0.124) and index operation at or after 2000 (HR, 0.258) were shown to be protective, while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced valve regurgitation after the index operation (HR, 9.00).

The researchers concluded that midterm Fontan survival was relatively favorable, pushing borderline repair may not be necessary, and “prophylactic banding” and the double-switch procedure should be looked on with caution for lower-risk patients.

“Our study also showed that survival was best in those having no associated lesions requiring operation, indicating that performing an anatomic repair for those not having associated lesions could be counterproductive,” Dr. Al-Omair concluded.

The webcast of the annual meeting presentation is available at www.aats.org.

Dr. Al-Omair reported that she and her colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Anatomic repair did not outperform physiologic repair in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA), according to a study presented by Maryam Al-Omair, M.D., of the University of Toronto at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Al-Omair and her colleagues hypothesized that patients undergoing anatomic repair for ccTGA would have superior systemic ventricular function and survival. However, their results showed that anatomic repair of ccTGA did not yield superior survival, compared with physiologic repair, and the long-term impact on systemic ventricular function was not certain.

Because of early evidence showing better outcomes of anatomic over physiologic repair for ccTGA, the surgical trend over time greatly favored the use of anatomic repair: At her team’s institution, anatomic repair went from 2.3% in the 1982-1989 period to 92.3% in the 2010-2015 period, Dr. Al-Omair said.

Their study assessed 200 patients (165 with biventricular ccTGA and 35 Fontan patients) who were managed from 1982 to 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The patient treatment groups were anatomic repair (38 patients), physiologic repair (89), single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (35), and palliated (no intracardiac repair) patients (38). The median follow-up was 3.4 years for anatomic repair, 13.5 years for physiologic repair, 7.5 years for single-ventricle repair, and 11.8 years with no repair (11.8 years), reflecting their change in practice.

The investigators followed the primary outcome of transplant-free survival and secondary outcomes of late systemic ventricular function and systemic atrioventricular valve function.

They found no significant difference in transplant-free survival at 20 years in the three repair groups assessed from 1892 to 2105: anatomic repair (58%), physiologic repair (71%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (78%). Looking at the latter period of 2000-2015 for 10-year transplant-free survival, they found similar results: anatomic repair (77%), physiologic repair (85%), and single-ventricle (Fontan) repair (100%).

They also found that transplant-free survival in patients who required no intracadiac repair and had no associated lesions such as ventral septal defect or ventral septal defect with pulmonary stenosis was nearly 95% at 25 years.

A multivariate analysis showed no independent predictors of mortality among the three treatments, patient age at index operation, or period of treatment, as well as the need for a permanent pacemaker, or moderately to severely reduced ventricular function or moderate to severe valve regurgitation after the index operation, according to Dr. Al-Omair.

For the secondary outcome of late systemic ventricular function, a multivariate analysis showed that two of the variables were independent predictors: Index operation at or after 2000 was shown to be protective (hazard ratio, 0.152), while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced ventricular function after the index operation (HR, 12.4).

For the secondary outcome of late systemic valve function, a multivariate analysis showed that three of the variables were independent predictors: Fontan operation (HR, 0.124) and index operation at or after 2000 (HR, 0.258) were shown to be protective, while a negative association was seen with moderately to severely reduced valve regurgitation after the index operation (HR, 9.00).

The researchers concluded that midterm Fontan survival was relatively favorable, pushing borderline repair may not be necessary, and “prophylactic banding” and the double-switch procedure should be looked on with caution for lower-risk patients.

“Our study also showed that survival was best in those having no associated lesions requiring operation, indicating that performing an anatomic repair for those not having associated lesions could be counterproductive,” Dr. Al-Omair concluded.

The webcast of the annual meeting presentation is available at www.aats.org.

Dr. Al-Omair reported that she and her colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE AATS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Performing an anatomic repair for ccTGA in patients without associated lesions could be counterproductive.

Major finding: There was no significant difference in transplant-free survival at 20 years among anatomic repair (58%), physiologic repair (71%), and single-ventricle repair (78%).

Data source: A single-institution study assessing 200 patients with ccGTA/Fontan who were managed from 1982 to 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Al-Omair reported that she and her colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

MRI-VA improves view of anomalous coronary arteries

Failure to achieve a rounded and unobstructed ostia in children who have surgery to repair anomalous coronary arteries can put these children at continued risk for sudden death, but cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy (VA) before and after the operation can give cardiologists a clear picture of a patient’s risk for sudden death and help direct ongoing management, according to a study in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:205-10).

“Cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy is an important tool for evaluating anomalous coronary anatomy, myocardial function, and ischemia and should be considered for initial and postoperative assessment of children with anomalous coronary arteries,” lead author Julie A. Brothers, MD, and her coauthors said in reporting their findings.

Anomalous coronary artery is a rare congenital condition in which the left coronary artery (LCA) originates from the right sinus or the right coronary artery (RCA) originates from the left coronary sinus. Dr. Brothers, a pediatric cardiologist, and her colleagues from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, studied nine male patients who had operations for anomalous coronary arteries during Feb. 2009-May 2015 in what they said is the first study to document anomalous coronary artery anatomy both before and after surgery. The patients’ average age was 14.1 years; seven had right anomalous coronary arteries and two had left anomalous arteries. After the operations, MRI-VA revealed that two patients still had narrowing in the neo-orifices.

Previous reports recommend surgical repair for all patients with anomalous LCA and for symptomatic patients with anomalous RCA anatomy (Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:691-7; Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:941-5). MRI-VA allows the surgical team to survey the ostial stenosis before the operation “as if standing within the vessel itself,” Dr. Brothers and her coauthors wrote. Afterward, MRI-VA lets the surgeon and team see if the operation succeeded in repairing the orifices.

In the study population, VA before surgery confirmed elliptical, slit-like orifices in all patients. The operations involved unroofing procedures; two patients also had detachment and resuspension procedures during surgery. After surgery, VA showed that seven patients had round, patent, unobstructed repaired orifices; but two had orifices that were still narrow and somewhat stenotic, Dr. Brothers and her coauthors said. The study group had postoperative MRI-VA an average of 8.6 months after surgery.

“The significance of these findings is unknown; however, if the proposed mechanism of ischemia is due to a slit-like orifice, a continued stenotic orifice may place subjects at risk for sudden death,” the researchers said. The two study patients with the narrowed, stenotic orifices have remained symptom free, with no evidence of ischemia on exercise stress test or cardiac MRI. “These subjects will need to be followed up in the future to monitor for progression or resolution,” the study authors wrote.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is more common in anomalous aortic origin of the LCA than the RCA, Dr. Brothers and her colleagues said. Thus, an elliptical, slit-like neo-orifice is a concern because it can become blocked during exercise, possibly leading to lethal ventricular arrhythmia, they said. Ischemia in patients with anomalous coronary artery seems to result from a cumulative effect of exercise.

Patients who undergo the modified unroofing procedure typically have electrocardiography and echocardiography afterward and then get cleared to return to competitive sports in about 3 months if their stress test indicates it. Dr. Brothers and her colleagues said this activity recommendation may need alteration for those patients who have had a heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest, because they may remain at increased risk of SCD after surgery. “At the very least, additional imaging, such as with MRI-VA, should be used in this population,” the study authors said.

While Dr. Brothers and her colleagues acknowledged the small sample size is a limitation of the study, they also pointed out that anomalous coronary artery is a rare disease. They also noted that high-quality VA images can be difficult to obtain in noncompliant patients or those have arrhythmia or irregular breathing. “The images obtained in this study were acquired at an institution very familiar with pediatric cardiac coronary MRI and would be appropriate for assessing the coronary ostia with VA,” they said.

Dr. Brothers and her coauthors had no financial disclosures.

The MRI technique that Dr. Brothers and her colleagues reported on can provide important details of the anomalous coronary anatomy and about myocardial function, Philip S. Naimo, MD, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, FRACS, of the Royal Children’s Hospital, University of Melbourne, wrote in their invited commentary. But, the ability to evaluate the neo-ostium after surgery had “particular value,” the commentators said (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Jul;152:211-12).

MRI with virtual angioscopy can fill help fill in the gaps where the significance of a narrowed neo-ostium is unknown, the commentators said. “The combination of anatomic information on the ostium size, shape, and location, as well as functional information on wall motion and myocardial perfusion, which can be provided by MRI-VA, would be particularly valuable in these patients,” they said.

They also pointed out that MRI-VA could be used in patients who have ongoing but otherwise undetected narrowing of the ostia after the unroofing procedure. At the same time, the technique will also require sufficient caseloads to maintain expertise. “It is safe to say that MRI-VA is here to stay,” Dr. Naimo, Dr. Buratto, and Dr. Konstantinov wrote. “The actual application of this virtual modality will need further refinement to be used routinely.”

The commentary authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

The MRI technique that Dr. Brothers and her colleagues reported on can provide important details of the anomalous coronary anatomy and about myocardial function, Philip S. Naimo, MD, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, FRACS, of the Royal Children’s Hospital, University of Melbourne, wrote in their invited commentary. But, the ability to evaluate the neo-ostium after surgery had “particular value,” the commentators said (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Jul;152:211-12).

MRI with virtual angioscopy can fill help fill in the gaps where the significance of a narrowed neo-ostium is unknown, the commentators said. “The combination of anatomic information on the ostium size, shape, and location, as well as functional information on wall motion and myocardial perfusion, which can be provided by MRI-VA, would be particularly valuable in these patients,” they said.

They also pointed out that MRI-VA could be used in patients who have ongoing but otherwise undetected narrowing of the ostia after the unroofing procedure. At the same time, the technique will also require sufficient caseloads to maintain expertise. “It is safe to say that MRI-VA is here to stay,” Dr. Naimo, Dr. Buratto, and Dr. Konstantinov wrote. “The actual application of this virtual modality will need further refinement to be used routinely.”

The commentary authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

The MRI technique that Dr. Brothers and her colleagues reported on can provide important details of the anomalous coronary anatomy and about myocardial function, Philip S. Naimo, MD, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and Igor Konstantinov, MD, PhD, FRACS, of the Royal Children’s Hospital, University of Melbourne, wrote in their invited commentary. But, the ability to evaluate the neo-ostium after surgery had “particular value,” the commentators said (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Jul;152:211-12).

MRI with virtual angioscopy can fill help fill in the gaps where the significance of a narrowed neo-ostium is unknown, the commentators said. “The combination of anatomic information on the ostium size, shape, and location, as well as functional information on wall motion and myocardial perfusion, which can be provided by MRI-VA, would be particularly valuable in these patients,” they said.

They also pointed out that MRI-VA could be used in patients who have ongoing but otherwise undetected narrowing of the ostia after the unroofing procedure. At the same time, the technique will also require sufficient caseloads to maintain expertise. “It is safe to say that MRI-VA is here to stay,” Dr. Naimo, Dr. Buratto, and Dr. Konstantinov wrote. “The actual application of this virtual modality will need further refinement to be used routinely.”

The commentary authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Failure to achieve a rounded and unobstructed ostia in children who have surgery to repair anomalous coronary arteries can put these children at continued risk for sudden death, but cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy (VA) before and after the operation can give cardiologists a clear picture of a patient’s risk for sudden death and help direct ongoing management, according to a study in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:205-10).

“Cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy is an important tool for evaluating anomalous coronary anatomy, myocardial function, and ischemia and should be considered for initial and postoperative assessment of children with anomalous coronary arteries,” lead author Julie A. Brothers, MD, and her coauthors said in reporting their findings.

Anomalous coronary artery is a rare congenital condition in which the left coronary artery (LCA) originates from the right sinus or the right coronary artery (RCA) originates from the left coronary sinus. Dr. Brothers, a pediatric cardiologist, and her colleagues from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, studied nine male patients who had operations for anomalous coronary arteries during Feb. 2009-May 2015 in what they said is the first study to document anomalous coronary artery anatomy both before and after surgery. The patients’ average age was 14.1 years; seven had right anomalous coronary arteries and two had left anomalous arteries. After the operations, MRI-VA revealed that two patients still had narrowing in the neo-orifices.

Previous reports recommend surgical repair for all patients with anomalous LCA and for symptomatic patients with anomalous RCA anatomy (Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:691-7; Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:941-5). MRI-VA allows the surgical team to survey the ostial stenosis before the operation “as if standing within the vessel itself,” Dr. Brothers and her coauthors wrote. Afterward, MRI-VA lets the surgeon and team see if the operation succeeded in repairing the orifices.

In the study population, VA before surgery confirmed elliptical, slit-like orifices in all patients. The operations involved unroofing procedures; two patients also had detachment and resuspension procedures during surgery. After surgery, VA showed that seven patients had round, patent, unobstructed repaired orifices; but two had orifices that were still narrow and somewhat stenotic, Dr. Brothers and her coauthors said. The study group had postoperative MRI-VA an average of 8.6 months after surgery.

“The significance of these findings is unknown; however, if the proposed mechanism of ischemia is due to a slit-like orifice, a continued stenotic orifice may place subjects at risk for sudden death,” the researchers said. The two study patients with the narrowed, stenotic orifices have remained symptom free, with no evidence of ischemia on exercise stress test or cardiac MRI. “These subjects will need to be followed up in the future to monitor for progression or resolution,” the study authors wrote.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is more common in anomalous aortic origin of the LCA than the RCA, Dr. Brothers and her colleagues said. Thus, an elliptical, slit-like neo-orifice is a concern because it can become blocked during exercise, possibly leading to lethal ventricular arrhythmia, they said. Ischemia in patients with anomalous coronary artery seems to result from a cumulative effect of exercise.

Patients who undergo the modified unroofing procedure typically have electrocardiography and echocardiography afterward and then get cleared to return to competitive sports in about 3 months if their stress test indicates it. Dr. Brothers and her colleagues said this activity recommendation may need alteration for those patients who have had a heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest, because they may remain at increased risk of SCD after surgery. “At the very least, additional imaging, such as with MRI-VA, should be used in this population,” the study authors said.

While Dr. Brothers and her colleagues acknowledged the small sample size is a limitation of the study, they also pointed out that anomalous coronary artery is a rare disease. They also noted that high-quality VA images can be difficult to obtain in noncompliant patients or those have arrhythmia or irregular breathing. “The images obtained in this study were acquired at an institution very familiar with pediatric cardiac coronary MRI and would be appropriate for assessing the coronary ostia with VA,” they said.

Dr. Brothers and her coauthors had no financial disclosures.

Failure to achieve a rounded and unobstructed ostia in children who have surgery to repair anomalous coronary arteries can put these children at continued risk for sudden death, but cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy (VA) before and after the operation can give cardiologists a clear picture of a patient’s risk for sudden death and help direct ongoing management, according to a study in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:205-10).

“Cardiac MRI with virtual angioscopy is an important tool for evaluating anomalous coronary anatomy, myocardial function, and ischemia and should be considered for initial and postoperative assessment of children with anomalous coronary arteries,” lead author Julie A. Brothers, MD, and her coauthors said in reporting their findings.

Anomalous coronary artery is a rare congenital condition in which the left coronary artery (LCA) originates from the right sinus or the right coronary artery (RCA) originates from the left coronary sinus. Dr. Brothers, a pediatric cardiologist, and her colleagues from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, studied nine male patients who had operations for anomalous coronary arteries during Feb. 2009-May 2015 in what they said is the first study to document anomalous coronary artery anatomy both before and after surgery. The patients’ average age was 14.1 years; seven had right anomalous coronary arteries and two had left anomalous arteries. After the operations, MRI-VA revealed that two patients still had narrowing in the neo-orifices.

Previous reports recommend surgical repair for all patients with anomalous LCA and for symptomatic patients with anomalous RCA anatomy (Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:691-7; Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:941-5). MRI-VA allows the surgical team to survey the ostial stenosis before the operation “as if standing within the vessel itself,” Dr. Brothers and her coauthors wrote. Afterward, MRI-VA lets the surgeon and team see if the operation succeeded in repairing the orifices.

In the study population, VA before surgery confirmed elliptical, slit-like orifices in all patients. The operations involved unroofing procedures; two patients also had detachment and resuspension procedures during surgery. After surgery, VA showed that seven patients had round, patent, unobstructed repaired orifices; but two had orifices that were still narrow and somewhat stenotic, Dr. Brothers and her coauthors said. The study group had postoperative MRI-VA an average of 8.6 months after surgery.

“The significance of these findings is unknown; however, if the proposed mechanism of ischemia is due to a slit-like orifice, a continued stenotic orifice may place subjects at risk for sudden death,” the researchers said. The two study patients with the narrowed, stenotic orifices have remained symptom free, with no evidence of ischemia on exercise stress test or cardiac MRI. “These subjects will need to be followed up in the future to monitor for progression or resolution,” the study authors wrote.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is more common in anomalous aortic origin of the LCA than the RCA, Dr. Brothers and her colleagues said. Thus, an elliptical, slit-like neo-orifice is a concern because it can become blocked during exercise, possibly leading to lethal ventricular arrhythmia, they said. Ischemia in patients with anomalous coronary artery seems to result from a cumulative effect of exercise.