User login

Severe Asthma: Allergic Asthma

6-year-old with loud wheezing, difficulty breathing

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

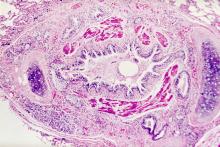

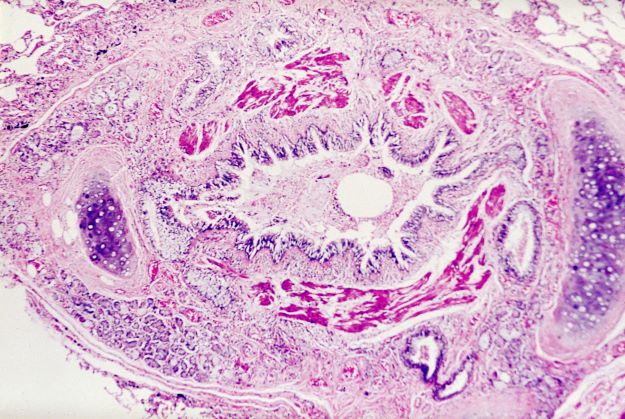

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 6-year-old girl presents with loud wheezing, difficulty breathing, and nasal flaring. She becomes particularly breathless while talking. The only abnormalities on chest CT are reduced airway luminal area and mucus plugs. Heart rate is 110 beats/min. Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is 94%. Skin examination is nonrevealing. The patient's mother cannot identify any factors that may have precipitated the episode.

Immunologic and Inflammatory Pathways of Severe Asthma

Severe Asthma: Challenges

History of asthma presents with wheezing and coughing

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 16-year-old female patient with a history of asthma presents with wheezing and coughing. Initial oxygen saturation is 89% and respiratory rate is 33 breaths/min. On physical examination, it is noted that the patient is using accessory muscles of ventilation. She was deemed to be having a severe asthma exacerbation and was treated with an inhaled bronchodilator. Several hours later, the patient's breathing frequency increased. Examination of the neck and chest revealed symmetrical swelling.