User login

Health Care Integration: Part 2

[for Part 1, click here.]

The waves of changes in health care have been flowing (crashing?) over us for the past couple years. One can barely get dry before the next one comes on. In psychiatry, we have several big waves hitting us now. Adoption of electronic health records. DSM-5. Integration of mental health, addiction, and somatic health care.

Integration of health care, to me, seems like the most challenging one. It involves changing many of our beliefs and practices about how behavioral health (I am using this BH term to encompass both mental health and addiction treatment) care is provided. Much of this new direction has been driven by a series of factors, including the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, the New Freedom Commission report in 2002, and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008.

A good resource for the MHPAEA is parityispersonal.org. The ultimate realization of parity, and of the end of the stigma so long attached to behavioral health, is the full integration of BH into the rest of health care, in the same way that cardiology and neurology are both integrated into health care. There is not a separate health insurance company to manage cardiology services. Neurology patients do not have to pay a higher co-pay for neurology services than they do for other specialty care services. And when you need to find a cardiologist in your insurance company’s provider directory, they are listed there with the other specialties, not in some other directory on some other website.

In my July 2012 column, entitled Health Care Integration, I discussed the process of integration in Maryland Medicaid and promised an update. Every state is addressing this to varying degrees and at different paces. Maryland’s efforts are led by Health Secretary Joshua Sharfstein, a pediatrician and public health expert who clearly gets the value of integration, and Chuck Milligan, the deputy secretary overseeing the entire project. A long process of stakeholder meetings culminated on Oct. 1 in a final recommendation report that can be found at http://dhmh.maryland.gov/bhd/SitePages/integrationefforts.aspx.

The report concludes: “While noting the strengths in the current system, including generally good access in each service domain (mental health, substance use treatment, and somatic care), the resulting report reached five conclusions: (1) benefit design and management across the domains are poorly aligned; (2) purchasing and financing are fragmented; (3) care management is not coordinated; (4) performance and risk are lacking; and (5) care integration needs improvement.”

The current system includes several managed care organizations (MCOs) that provide somatic and addiction care services, and a single administrative services organization (ASO) – Value Options – that is responsible for mental health services. The final recommendation to Secretary Sharfstein is “that Maryland pursue a transformative behavioral health carve-out that combines treatment for specialty mental illness and substance use disorders under the management of a single administrative services organization (ASO).” The transformation part refers to the development of a “performance-based ASO,” whose features include the following:

- Financial performance risk (likely including shared savings) at the ASO level;

- Financial performance risk (which could include shared savings) at the behavioral health provider level;

- Incorporation of behavioral health financial incentives at the primary care and MCO level; and

- Incorporation of non-financial tools that distinguish providers who achieve positive outcomes from providers who achieve average or poor outcomes, including tools such as differential rules for prior authorization, utilization review, and consumer self-referral.

Other changes might include greater integration between the ASO and the MCOs:

- Requiring an MCO to assign a care coordinator when one of its members receives services in the specialty behavioral health system;

- Developing policies and approaches to coordinate (or integrate) primary care with the specialty behavioral health services provided through the new behavioral Health Home;

- Increasing bi-directional data sharing between the MCOs and the ASO to improve beneficiary care, which could include an approach that aligns electronic health records; and

- Shared savings models across somatic and behavioral health.

I think we are moving in the right direction, despite some criticism in the path to get there. We are making less of an issue now about what model to choose (Model 2 has been chosen, the ASO model), and beginning to focus more on the details. Based on the Principles of Integration from the Maryland Psychiatric Association (enumerated in Part 1 of this series), the last four points, such as care coordination, bi-directional data-sharing, shared savings and risk, and stakeholder oversight and data transparency, are all elements that MUST (not “may”) be included.

One interesting development is that the addiction community is largely refuting previous attributions that the integration of addictions with primary care was a disaster, and is now clarifying that – while there were early challenges – things are just fine now, thank you very much. So they are quite concerned about losing their advances when addictions get carved back out of somatic care and included in mental health.

The primary care community, led by MedChi, the state medical society, is also backing the integration principles that the MPS has championed. And we are now hearing from some MCOs and hospitals that a fully integrated approach, all rolled into one or several MCOs, is preferred. A hearing before the legislature was to occur last week, but Hurricane Sandy interfered. Public comments are being collected until Nov. 9, and the rescheduled hearing is set for Dec. 18.

I’ll be back before Christmas with Part 3. I am certain that there are at least a couple states going through the same discussions that we are going through. Log in to CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY NEWS and post your comments so we can all learn from one anothers’ experiences.

—Steven Roy Davis, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog and drdavissATgmailDOTcom.

[for Part 1, click here.]

The waves of changes in health care have been flowing (crashing?) over us for the past couple years. One can barely get dry before the next one comes on. In psychiatry, we have several big waves hitting us now. Adoption of electronic health records. DSM-5. Integration of mental health, addiction, and somatic health care.

Integration of health care, to me, seems like the most challenging one. It involves changing many of our beliefs and practices about how behavioral health (I am using this BH term to encompass both mental health and addiction treatment) care is provided. Much of this new direction has been driven by a series of factors, including the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, the New Freedom Commission report in 2002, and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008.

A good resource for the MHPAEA is parityispersonal.org. The ultimate realization of parity, and of the end of the stigma so long attached to behavioral health, is the full integration of BH into the rest of health care, in the same way that cardiology and neurology are both integrated into health care. There is not a separate health insurance company to manage cardiology services. Neurology patients do not have to pay a higher co-pay for neurology services than they do for other specialty care services. And when you need to find a cardiologist in your insurance company’s provider directory, they are listed there with the other specialties, not in some other directory on some other website.

In my July 2012 column, entitled Health Care Integration, I discussed the process of integration in Maryland Medicaid and promised an update. Every state is addressing this to varying degrees and at different paces. Maryland’s efforts are led by Health Secretary Joshua Sharfstein, a pediatrician and public health expert who clearly gets the value of integration, and Chuck Milligan, the deputy secretary overseeing the entire project. A long process of stakeholder meetings culminated on Oct. 1 in a final recommendation report that can be found at http://dhmh.maryland.gov/bhd/SitePages/integrationefforts.aspx.

The report concludes: “While noting the strengths in the current system, including generally good access in each service domain (mental health, substance use treatment, and somatic care), the resulting report reached five conclusions: (1) benefit design and management across the domains are poorly aligned; (2) purchasing and financing are fragmented; (3) care management is not coordinated; (4) performance and risk are lacking; and (5) care integration needs improvement.”

The current system includes several managed care organizations (MCOs) that provide somatic and addiction care services, and a single administrative services organization (ASO) – Value Options – that is responsible for mental health services. The final recommendation to Secretary Sharfstein is “that Maryland pursue a transformative behavioral health carve-out that combines treatment for specialty mental illness and substance use disorders under the management of a single administrative services organization (ASO).” The transformation part refers to the development of a “performance-based ASO,” whose features include the following:

- Financial performance risk (likely including shared savings) at the ASO level;

- Financial performance risk (which could include shared savings) at the behavioral health provider level;

- Incorporation of behavioral health financial incentives at the primary care and MCO level; and

- Incorporation of non-financial tools that distinguish providers who achieve positive outcomes from providers who achieve average or poor outcomes, including tools such as differential rules for prior authorization, utilization review, and consumer self-referral.

Other changes might include greater integration between the ASO and the MCOs:

- Requiring an MCO to assign a care coordinator when one of its members receives services in the specialty behavioral health system;

- Developing policies and approaches to coordinate (or integrate) primary care with the specialty behavioral health services provided through the new behavioral Health Home;

- Increasing bi-directional data sharing between the MCOs and the ASO to improve beneficiary care, which could include an approach that aligns electronic health records; and

- Shared savings models across somatic and behavioral health.

I think we are moving in the right direction, despite some criticism in the path to get there. We are making less of an issue now about what model to choose (Model 2 has been chosen, the ASO model), and beginning to focus more on the details. Based on the Principles of Integration from the Maryland Psychiatric Association (enumerated in Part 1 of this series), the last four points, such as care coordination, bi-directional data-sharing, shared savings and risk, and stakeholder oversight and data transparency, are all elements that MUST (not “may”) be included.

One interesting development is that the addiction community is largely refuting previous attributions that the integration of addictions with primary care was a disaster, and is now clarifying that – while there were early challenges – things are just fine now, thank you very much. So they are quite concerned about losing their advances when addictions get carved back out of somatic care and included in mental health.

The primary care community, led by MedChi, the state medical society, is also backing the integration principles that the MPS has championed. And we are now hearing from some MCOs and hospitals that a fully integrated approach, all rolled into one or several MCOs, is preferred. A hearing before the legislature was to occur last week, but Hurricane Sandy interfered. Public comments are being collected until Nov. 9, and the rescheduled hearing is set for Dec. 18.

I’ll be back before Christmas with Part 3. I am certain that there are at least a couple states going through the same discussions that we are going through. Log in to CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY NEWS and post your comments so we can all learn from one anothers’ experiences.

—Steven Roy Davis, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog and drdavissATgmailDOTcom.

[for Part 1, click here.]

The waves of changes in health care have been flowing (crashing?) over us for the past couple years. One can barely get dry before the next one comes on. In psychiatry, we have several big waves hitting us now. Adoption of electronic health records. DSM-5. Integration of mental health, addiction, and somatic health care.

Integration of health care, to me, seems like the most challenging one. It involves changing many of our beliefs and practices about how behavioral health (I am using this BH term to encompass both mental health and addiction treatment) care is provided. Much of this new direction has been driven by a series of factors, including the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, the New Freedom Commission report in 2002, and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008.

A good resource for the MHPAEA is parityispersonal.org. The ultimate realization of parity, and of the end of the stigma so long attached to behavioral health, is the full integration of BH into the rest of health care, in the same way that cardiology and neurology are both integrated into health care. There is not a separate health insurance company to manage cardiology services. Neurology patients do not have to pay a higher co-pay for neurology services than they do for other specialty care services. And when you need to find a cardiologist in your insurance company’s provider directory, they are listed there with the other specialties, not in some other directory on some other website.

In my July 2012 column, entitled Health Care Integration, I discussed the process of integration in Maryland Medicaid and promised an update. Every state is addressing this to varying degrees and at different paces. Maryland’s efforts are led by Health Secretary Joshua Sharfstein, a pediatrician and public health expert who clearly gets the value of integration, and Chuck Milligan, the deputy secretary overseeing the entire project. A long process of stakeholder meetings culminated on Oct. 1 in a final recommendation report that can be found at http://dhmh.maryland.gov/bhd/SitePages/integrationefforts.aspx.

The report concludes: “While noting the strengths in the current system, including generally good access in each service domain (mental health, substance use treatment, and somatic care), the resulting report reached five conclusions: (1) benefit design and management across the domains are poorly aligned; (2) purchasing and financing are fragmented; (3) care management is not coordinated; (4) performance and risk are lacking; and (5) care integration needs improvement.”

The current system includes several managed care organizations (MCOs) that provide somatic and addiction care services, and a single administrative services organization (ASO) – Value Options – that is responsible for mental health services. The final recommendation to Secretary Sharfstein is “that Maryland pursue a transformative behavioral health carve-out that combines treatment for specialty mental illness and substance use disorders under the management of a single administrative services organization (ASO).” The transformation part refers to the development of a “performance-based ASO,” whose features include the following:

- Financial performance risk (likely including shared savings) at the ASO level;

- Financial performance risk (which could include shared savings) at the behavioral health provider level;

- Incorporation of behavioral health financial incentives at the primary care and MCO level; and

- Incorporation of non-financial tools that distinguish providers who achieve positive outcomes from providers who achieve average or poor outcomes, including tools such as differential rules for prior authorization, utilization review, and consumer self-referral.

Other changes might include greater integration between the ASO and the MCOs:

- Requiring an MCO to assign a care coordinator when one of its members receives services in the specialty behavioral health system;

- Developing policies and approaches to coordinate (or integrate) primary care with the specialty behavioral health services provided through the new behavioral Health Home;

- Increasing bi-directional data sharing between the MCOs and the ASO to improve beneficiary care, which could include an approach that aligns electronic health records; and

- Shared savings models across somatic and behavioral health.

I think we are moving in the right direction, despite some criticism in the path to get there. We are making less of an issue now about what model to choose (Model 2 has been chosen, the ASO model), and beginning to focus more on the details. Based on the Principles of Integration from the Maryland Psychiatric Association (enumerated in Part 1 of this series), the last four points, such as care coordination, bi-directional data-sharing, shared savings and risk, and stakeholder oversight and data transparency, are all elements that MUST (not “may”) be included.

One interesting development is that the addiction community is largely refuting previous attributions that the integration of addictions with primary care was a disaster, and is now clarifying that – while there were early challenges – things are just fine now, thank you very much. So they are quite concerned about losing their advances when addictions get carved back out of somatic care and included in mental health.

The primary care community, led by MedChi, the state medical society, is also backing the integration principles that the MPS has championed. And we are now hearing from some MCOs and hospitals that a fully integrated approach, all rolled into one or several MCOs, is preferred. A hearing before the legislature was to occur last week, but Hurricane Sandy interfered. Public comments are being collected until Nov. 9, and the rescheduled hearing is set for Dec. 18.

I’ll be back before Christmas with Part 3. I am certain that there are at least a couple states going through the same discussions that we are going through. Log in to CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY NEWS and post your comments so we can all learn from one anothers’ experiences.

—Steven Roy Davis, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog and drdavissATgmailDOTcom.

'Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation': A Review

I was a medical student in Manhattan in the late 1980s. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to go into psychiatry, and I watched the psychoanalysts and psychopharmacologists chase each other back and forth across town from institution to institution, debating questions of nature vs. nurture for the both the cause and cure of mental disorders.

When I moved to Baltimore to begin my psychiatry residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital, I was introduced to a way of thinking about human behavior and emotions that involved considering the individual from four different perspectives as described by our chairman, Dr. Paul McHugh, and our residency director, Dr. Phillip Slavney, in their book, The Perspectives of Psychiatry. At the time, this approach seemed almost obvious to me; of course the causes of psychopathology were multifactorial; how could they not be?

Fast-forward two decades and what seemed obvious to a newly minted psychiatry resident no longer feels quiet so evident. We’ve become a field of diagnosis by checklist and rapid-fire appointments to ask about symptoms and side effects. In fact, most psychiatric care is rendered by primary care physicians with little formal training in psychiatric diagnosis. Twenty years later, and it seems we’ve lost our curiosity (“no time”) and with that, the inclination to learn about a patient’s difficulties in the context of not only a disease, but also by giving consideration to their motivated behaviors, their individual temperaments, and their complete life stories.

So on our current landscape of checklist diagnosis and the full-court press by insurers to reimburse psychiatrists best for brief visits, it is refreshing to read Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation, A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying The Perspectives of Psychiatry, by two of my residency classmates, Dr. Margaret S. Chisolm and Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, M.H.S. Nothing about this book is about learning to diagnose in Chinese menu format, or about rushed appointments with patients; instead it is about how to do thoughtful and caring evaluations (including, but not limited to, diagnoses) of patients with emotional and/or behavioral turmoil.

The authors begin with a hint of humor – probably best understood by those of us who live in Charm City – by presenting the historical case history of Baltimore poet Edgar Allen Poe, done first as a typical psychiatric presentation, and then as a full case study per the four perspectives. They go on to present a series of patient case histories, beginning with reconstructed interviews, an analysis that integrates a multifactorial approach to understanding the problems, a conclusion, and summary points.

One of the treasures of this book is that the back-and-forth dialogue of the interviews is included, illustrating to students exactly which words an experienced clinician might use to elicit specific material, and giving the reader the sense of being in the room during the interview. The wording is designed to convey empathy, warmth, and to put the patient at ease. And while the case studies are comprehensive, the book is done as an engaging, concise, and quick read.

Whether or not psychiatrists choose to practice in time-pressured environments, teaching institutions need to remain a place where our students learn to evaluate patients in a systematic and comprehensive manner and, in psychiatry, this is not a quick process and it does not involve cutting corners or boiling the complex work of psychiatric evaluations down to checklists.

Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation is the best go-to book I have seen for teaching thoughtful evaluation.

Please also see Dr. Chisolm’s guest post about her book on the main Shrink Rap blog here.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

Dr. Miller’s books and novels are listed here.

I was a medical student in Manhattan in the late 1980s. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to go into psychiatry, and I watched the psychoanalysts and psychopharmacologists chase each other back and forth across town from institution to institution, debating questions of nature vs. nurture for the both the cause and cure of mental disorders.

When I moved to Baltimore to begin my psychiatry residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital, I was introduced to a way of thinking about human behavior and emotions that involved considering the individual from four different perspectives as described by our chairman, Dr. Paul McHugh, and our residency director, Dr. Phillip Slavney, in their book, The Perspectives of Psychiatry. At the time, this approach seemed almost obvious to me; of course the causes of psychopathology were multifactorial; how could they not be?

Fast-forward two decades and what seemed obvious to a newly minted psychiatry resident no longer feels quiet so evident. We’ve become a field of diagnosis by checklist and rapid-fire appointments to ask about symptoms and side effects. In fact, most psychiatric care is rendered by primary care physicians with little formal training in psychiatric diagnosis. Twenty years later, and it seems we’ve lost our curiosity (“no time”) and with that, the inclination to learn about a patient’s difficulties in the context of not only a disease, but also by giving consideration to their motivated behaviors, their individual temperaments, and their complete life stories.

So on our current landscape of checklist diagnosis and the full-court press by insurers to reimburse psychiatrists best for brief visits, it is refreshing to read Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation, A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying The Perspectives of Psychiatry, by two of my residency classmates, Dr. Margaret S. Chisolm and Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, M.H.S. Nothing about this book is about learning to diagnose in Chinese menu format, or about rushed appointments with patients; instead it is about how to do thoughtful and caring evaluations (including, but not limited to, diagnoses) of patients with emotional and/or behavioral turmoil.

The authors begin with a hint of humor – probably best understood by those of us who live in Charm City – by presenting the historical case history of Baltimore poet Edgar Allen Poe, done first as a typical psychiatric presentation, and then as a full case study per the four perspectives. They go on to present a series of patient case histories, beginning with reconstructed interviews, an analysis that integrates a multifactorial approach to understanding the problems, a conclusion, and summary points.

One of the treasures of this book is that the back-and-forth dialogue of the interviews is included, illustrating to students exactly which words an experienced clinician might use to elicit specific material, and giving the reader the sense of being in the room during the interview. The wording is designed to convey empathy, warmth, and to put the patient at ease. And while the case studies are comprehensive, the book is done as an engaging, concise, and quick read.

Whether or not psychiatrists choose to practice in time-pressured environments, teaching institutions need to remain a place where our students learn to evaluate patients in a systematic and comprehensive manner and, in psychiatry, this is not a quick process and it does not involve cutting corners or boiling the complex work of psychiatric evaluations down to checklists.

Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation is the best go-to book I have seen for teaching thoughtful evaluation.

Please also see Dr. Chisolm’s guest post about her book on the main Shrink Rap blog here.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

Dr. Miller’s books and novels are listed here.

I was a medical student in Manhattan in the late 1980s. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to go into psychiatry, and I watched the psychoanalysts and psychopharmacologists chase each other back and forth across town from institution to institution, debating questions of nature vs. nurture for the both the cause and cure of mental disorders.

When I moved to Baltimore to begin my psychiatry residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital, I was introduced to a way of thinking about human behavior and emotions that involved considering the individual from four different perspectives as described by our chairman, Dr. Paul McHugh, and our residency director, Dr. Phillip Slavney, in their book, The Perspectives of Psychiatry. At the time, this approach seemed almost obvious to me; of course the causes of psychopathology were multifactorial; how could they not be?

Fast-forward two decades and what seemed obvious to a newly minted psychiatry resident no longer feels quiet so evident. We’ve become a field of diagnosis by checklist and rapid-fire appointments to ask about symptoms and side effects. In fact, most psychiatric care is rendered by primary care physicians with little formal training in psychiatric diagnosis. Twenty years later, and it seems we’ve lost our curiosity (“no time”) and with that, the inclination to learn about a patient’s difficulties in the context of not only a disease, but also by giving consideration to their motivated behaviors, their individual temperaments, and their complete life stories.

So on our current landscape of checklist diagnosis and the full-court press by insurers to reimburse psychiatrists best for brief visits, it is refreshing to read Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation, A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying The Perspectives of Psychiatry, by two of my residency classmates, Dr. Margaret S. Chisolm and Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, M.H.S. Nothing about this book is about learning to diagnose in Chinese menu format, or about rushed appointments with patients; instead it is about how to do thoughtful and caring evaluations (including, but not limited to, diagnoses) of patients with emotional and/or behavioral turmoil.

The authors begin with a hint of humor – probably best understood by those of us who live in Charm City – by presenting the historical case history of Baltimore poet Edgar Allen Poe, done first as a typical psychiatric presentation, and then as a full case study per the four perspectives. They go on to present a series of patient case histories, beginning with reconstructed interviews, an analysis that integrates a multifactorial approach to understanding the problems, a conclusion, and summary points.

One of the treasures of this book is that the back-and-forth dialogue of the interviews is included, illustrating to students exactly which words an experienced clinician might use to elicit specific material, and giving the reader the sense of being in the room during the interview. The wording is designed to convey empathy, warmth, and to put the patient at ease. And while the case studies are comprehensive, the book is done as an engaging, concise, and quick read.

Whether or not psychiatrists choose to practice in time-pressured environments, teaching institutions need to remain a place where our students learn to evaluate patients in a systematic and comprehensive manner and, in psychiatry, this is not a quick process and it does not involve cutting corners or boiling the complex work of psychiatric evaluations down to checklists.

Systematic Psychiatric Evaluation is the best go-to book I have seen for teaching thoughtful evaluation.

Please also see Dr. Chisolm’s guest post about her book on the main Shrink Rap blog here.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

Dr. Miller’s books and novels are listed here.

New Study Debunks the 'Mad Artistic Genius' Myth

In the October issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, Dr. Simon Kyaga and his colleagues examined the relationship between various psychiatric disorders and the creative occupations. They used Swedish census data as well as the medical and mortality registry information of more than 1.1 million subjects involved in either scientific or traditional creative professions. A scientific occupation was considered creative if it involved academic research and teaching at a university level. The traditional creative professions were defined as visual or non-visual artists, with particular attention paid to writers.

An additional control group was added for comparison to a “lesser creative” occupation, specifically accountants and auditors. First degree relatives of each subject were also included. The authors considered a wide variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, autism, anorexia nervosa, ADHD, and substance use disorders.

The study showed that there was no overall difference between the creative and lesser creative occupations with regard to any psychiatric disorder other than bipolar disorder, which was more prevalent among scientific creatives.

Participation in a creative occupation appeared to be protective for the development of most disorders, and decreased the likelihood of suicide.

Being in a creative profession was associated with a family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The authors speculated that creativity and unconventional thinking exist along a spectrum with psychopathology, and that there is an overall evolutionary benefit. Some degree of pathology leads to productivity, while too much is pathological.

Writers were an exception to these findings. Authors were twice as likely as other creative professionals to have schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and were at increased risk of both depression and substance abuse. Writers, and poets in particular, were at an increased risk of suicide even in the absence of a psychiatric diagnosis.

There were several unique aspects to this study: the extremely large number of subjects, the 40-year follow-up period, and the extensive list of psychiatric disorders that were included. It was also unique because it included “everyday” artists – creative individuals who were not celebrity figures or award-winning authors. Thus, the study may be more reflective of the real-world experience of most visual and verbal artistic professionals.

While I found the research fascinating, it was not designed to answer the question of why creativity may protect against mental illness for most professions or why writers may be particularly vulnerable. Certainly, there are aspects of an artist’s life that would affect emotional functioning: living in a society were artistic accomplishments are less valued or rewarded, being professionally isolated or being involved in an activity that requires a considerable investment of one’s identity or some degree of public personal disclosure. The creative endeavor itself may compensate for all this.

The study also isn’t able to answer the question of how best to care for the mentally ill artist or the role of the creative process in recovery from mental illness. Nevertheless, this paper will hopefully put to rest the myth of the mad but tragic artistic genius. While creativity and madness may make for a compelling narrative, the reality of serious mental illness and suicide is a much uglier picture.

—Annette Hanson, M.D.

DR. HANSON is a forensic psychiatrist and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

In the October issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, Dr. Simon Kyaga and his colleagues examined the relationship between various psychiatric disorders and the creative occupations. They used Swedish census data as well as the medical and mortality registry information of more than 1.1 million subjects involved in either scientific or traditional creative professions. A scientific occupation was considered creative if it involved academic research and teaching at a university level. The traditional creative professions were defined as visual or non-visual artists, with particular attention paid to writers.

An additional control group was added for comparison to a “lesser creative” occupation, specifically accountants and auditors. First degree relatives of each subject were also included. The authors considered a wide variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, autism, anorexia nervosa, ADHD, and substance use disorders.

The study showed that there was no overall difference between the creative and lesser creative occupations with regard to any psychiatric disorder other than bipolar disorder, which was more prevalent among scientific creatives.

Participation in a creative occupation appeared to be protective for the development of most disorders, and decreased the likelihood of suicide.

Being in a creative profession was associated with a family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The authors speculated that creativity and unconventional thinking exist along a spectrum with psychopathology, and that there is an overall evolutionary benefit. Some degree of pathology leads to productivity, while too much is pathological.

Writers were an exception to these findings. Authors were twice as likely as other creative professionals to have schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and were at increased risk of both depression and substance abuse. Writers, and poets in particular, were at an increased risk of suicide even in the absence of a psychiatric diagnosis.

There were several unique aspects to this study: the extremely large number of subjects, the 40-year follow-up period, and the extensive list of psychiatric disorders that were included. It was also unique because it included “everyday” artists – creative individuals who were not celebrity figures or award-winning authors. Thus, the study may be more reflective of the real-world experience of most visual and verbal artistic professionals.

While I found the research fascinating, it was not designed to answer the question of why creativity may protect against mental illness for most professions or why writers may be particularly vulnerable. Certainly, there are aspects of an artist’s life that would affect emotional functioning: living in a society were artistic accomplishments are less valued or rewarded, being professionally isolated or being involved in an activity that requires a considerable investment of one’s identity or some degree of public personal disclosure. The creative endeavor itself may compensate for all this.

The study also isn’t able to answer the question of how best to care for the mentally ill artist or the role of the creative process in recovery from mental illness. Nevertheless, this paper will hopefully put to rest the myth of the mad but tragic artistic genius. While creativity and madness may make for a compelling narrative, the reality of serious mental illness and suicide is a much uglier picture.

—Annette Hanson, M.D.

DR. HANSON is a forensic psychiatrist and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

In the October issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, Dr. Simon Kyaga and his colleagues examined the relationship between various psychiatric disorders and the creative occupations. They used Swedish census data as well as the medical and mortality registry information of more than 1.1 million subjects involved in either scientific or traditional creative professions. A scientific occupation was considered creative if it involved academic research and teaching at a university level. The traditional creative professions were defined as visual or non-visual artists, with particular attention paid to writers.

An additional control group was added for comparison to a “lesser creative” occupation, specifically accountants and auditors. First degree relatives of each subject were also included. The authors considered a wide variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, autism, anorexia nervosa, ADHD, and substance use disorders.

The study showed that there was no overall difference between the creative and lesser creative occupations with regard to any psychiatric disorder other than bipolar disorder, which was more prevalent among scientific creatives.

Participation in a creative occupation appeared to be protective for the development of most disorders, and decreased the likelihood of suicide.

Being in a creative profession was associated with a family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The authors speculated that creativity and unconventional thinking exist along a spectrum with psychopathology, and that there is an overall evolutionary benefit. Some degree of pathology leads to productivity, while too much is pathological.

Writers were an exception to these findings. Authors were twice as likely as other creative professionals to have schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and were at increased risk of both depression and substance abuse. Writers, and poets in particular, were at an increased risk of suicide even in the absence of a psychiatric diagnosis.

There were several unique aspects to this study: the extremely large number of subjects, the 40-year follow-up period, and the extensive list of psychiatric disorders that were included. It was also unique because it included “everyday” artists – creative individuals who were not celebrity figures or award-winning authors. Thus, the study may be more reflective of the real-world experience of most visual and verbal artistic professionals.

While I found the research fascinating, it was not designed to answer the question of why creativity may protect against mental illness for most professions or why writers may be particularly vulnerable. Certainly, there are aspects of an artist’s life that would affect emotional functioning: living in a society were artistic accomplishments are less valued or rewarded, being professionally isolated or being involved in an activity that requires a considerable investment of one’s identity or some degree of public personal disclosure. The creative endeavor itself may compensate for all this.

The study also isn’t able to answer the question of how best to care for the mentally ill artist or the role of the creative process in recovery from mental illness. Nevertheless, this paper will hopefully put to rest the myth of the mad but tragic artistic genius. While creativity and madness may make for a compelling narrative, the reality of serious mental illness and suicide is a much uglier picture.

—Annette Hanson, M.D.

DR. HANSON is a forensic psychiatrist and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

World Mental Health Day: Oct. 10

Today, Oct. 10, 2012, is the anniversary of World Mental Health Day, started by the World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH) 20 years ago. Many other advocacy organizations and governments have since recognized this day as a mechanism to promote mental health, including National Depression Screening Day in the United States (which is the next day, on Oct. 11).

This year’s theme is Depression: A Global Crisis. Depression has long been a significant problem globally, but has particularly taken hold in recent years, associated with the global economic downturn. Some facts from the WFMH, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) about depression are rather alarming:

- More than 350 millionMore than 350 million people worldwide have depression

- Unipolar depression was the third-leading cause of global disease burden in 2004

- It is expected to be the #1 leading cause by 2030

- The World Mental Health Survey of people in 17 countries found that 1 in 20 had an episode of depression in the past year

- Depression is the leading cause of disability in terms of work years lost to disease

- 16% of U.S. adults have a history of at least one episode of depression... the average age of onset is 32

- 3,000: number of people lost to suicide ... every day (most have depression)

- 60,000: number of people attempting suicide ... every day

- Every 1% rise in unemployment is associated with a 0.79% rise in suicides in nonelderly adults

- Greece has experienced a 36% increase in suicide attempts since its economic crisis began

- Less than half of people with depression receive any treatment

- Only 20% (in the United States) receive minimally adequate treatment

- At least one-sixth of people with depression actually have bipolar depression

- People with diabetes or heart disease who also have depression do more poorly and have a higher mortality

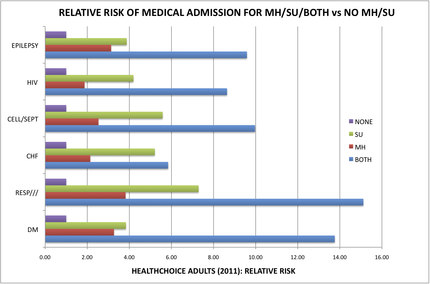

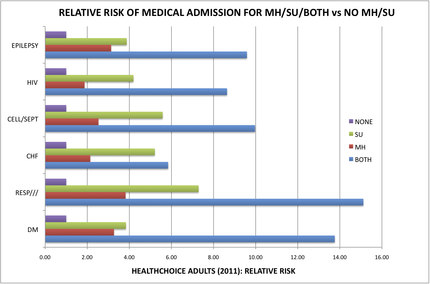

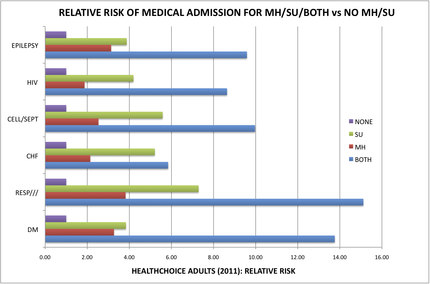

- People on Medicaid who have a chronic medical condition as well as a mental health diagnosis are hospitalized as much as 2-4 times more often for their medical condition than those who do not have a mental health diagnosis

- If they also have an addiction diagnosis, they are hospitalized 8-15 times more often for their chronic medical condition

Here is a list of resources for more information on depression:

- Take a free screening for depression, bipolar, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders

—Steven R. Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.

Today, Oct. 10, 2012, is the anniversary of World Mental Health Day, started by the World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH) 20 years ago. Many other advocacy organizations and governments have since recognized this day as a mechanism to promote mental health, including National Depression Screening Day in the United States (which is the next day, on Oct. 11).

This year’s theme is Depression: A Global Crisis. Depression has long been a significant problem globally, but has particularly taken hold in recent years, associated with the global economic downturn. Some facts from the WFMH, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) about depression are rather alarming:

- More than 350 millionMore than 350 million people worldwide have depression

- Unipolar depression was the third-leading cause of global disease burden in 2004

- It is expected to be the #1 leading cause by 2030

- The World Mental Health Survey of people in 17 countries found that 1 in 20 had an episode of depression in the past year

- Depression is the leading cause of disability in terms of work years lost to disease

- 16% of U.S. adults have a history of at least one episode of depression... the average age of onset is 32

- 3,000: number of people lost to suicide ... every day (most have depression)

- 60,000: number of people attempting suicide ... every day

- Every 1% rise in unemployment is associated with a 0.79% rise in suicides in nonelderly adults

- Greece has experienced a 36% increase in suicide attempts since its economic crisis began

- Less than half of people with depression receive any treatment

- Only 20% (in the United States) receive minimally adequate treatment

- At least one-sixth of people with depression actually have bipolar depression

- People with diabetes or heart disease who also have depression do more poorly and have a higher mortality

- People on Medicaid who have a chronic medical condition as well as a mental health diagnosis are hospitalized as much as 2-4 times more often for their medical condition than those who do not have a mental health diagnosis

- If they also have an addiction diagnosis, they are hospitalized 8-15 times more often for their chronic medical condition

Here is a list of resources for more information on depression:

- Take a free screening for depression, bipolar, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders

—Steven R. Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.

Today, Oct. 10, 2012, is the anniversary of World Mental Health Day, started by the World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH) 20 years ago. Many other advocacy organizations and governments have since recognized this day as a mechanism to promote mental health, including National Depression Screening Day in the United States (which is the next day, on Oct. 11).

This year’s theme is Depression: A Global Crisis. Depression has long been a significant problem globally, but has particularly taken hold in recent years, associated with the global economic downturn. Some facts from the WFMH, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) about depression are rather alarming:

- More than 350 millionMore than 350 million people worldwide have depression

- Unipolar depression was the third-leading cause of global disease burden in 2004

- It is expected to be the #1 leading cause by 2030

- The World Mental Health Survey of people in 17 countries found that 1 in 20 had an episode of depression in the past year

- Depression is the leading cause of disability in terms of work years lost to disease

- 16% of U.S. adults have a history of at least one episode of depression... the average age of onset is 32

- 3,000: number of people lost to suicide ... every day (most have depression)

- 60,000: number of people attempting suicide ... every day

- Every 1% rise in unemployment is associated with a 0.79% rise in suicides in nonelderly adults

- Greece has experienced a 36% increase in suicide attempts since its economic crisis began

- Less than half of people with depression receive any treatment

- Only 20% (in the United States) receive minimally adequate treatment

- At least one-sixth of people with depression actually have bipolar depression

- People with diabetes or heart disease who also have depression do more poorly and have a higher mortality

- People on Medicaid who have a chronic medical condition as well as a mental health diagnosis are hospitalized as much as 2-4 times more often for their medical condition than those who do not have a mental health diagnosis

- If they also have an addiction diagnosis, they are hospitalized 8-15 times more often for their chronic medical condition

Here is a list of resources for more information on depression:

- Take a free screening for depression, bipolar, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders

—Steven R. Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.

The Med Check Racket: More Controversy

A reader from Carlisle, Pa., writes:

If Dr. Miller has ever practiced in a community mental health setting, she gives no evidence of it in her article. The title itself being offensive, the suggestion that “the economics might be clear” eludes me. The economics are not at all clear to me.

I am employed (and therefore have no personal stake in the fee schedule whatsoever) by a community mental health center that serves two counties in south-central Pennsylvania. My practice includes, I am told, about 1,400 patients, the vast majority of them without insurance other than Medicaid and/or Medicare. Many of these patients have no coverage for prescription medications, or have a carrier whose formulary is so restrictive as to require many hours of a nurse’s time to "prior auth" a mainstream medication, or to beg the drug rep for samples.

So, 1,400 patients, 40-hour/week work schedule: You do the math. The med-check “racket” here provides service for patients to which they would not otherwise have access.

The reader was offended by my post “The Med Check Racket,” which appeared on this blog in July, and in the August print edition of Clinical Psychiatry News. He is in good company; my article was so offensive to Dr. Anne Hanson, my co-blogger/author and good friend, that she responded the following week with her own post titled, “Those Evil Med Checks,” where she talks about her clinical work in the prisons. If you haven’t read it, please do.

I have worked at a number of community mental health centers. When I finished residency, I worked half-time at a CMHC, while I simultaneously began a private practice. I left that job to become medical director of a different CMHC, a position that enabled me to learn about the finances of public mental health clinics.

Since 1998, I have consulted part-time to the Johns Hopkins Community Psychiatry Program, and for a few years, I volunteered for HealthCare for the Homeless. I do know at least a little about community psychiatry.

“The Med Check Racket” was titled by a friend who complained to me about a private practice psychiatrist who sees him for 15 minutes every 6 months and asks a few, checklist-style, questions. I borrowed his comment as a title because I thought it was provocative, but I did not intend it to be offensive. Obviously, I was wrong!

I still believe that it does our profession no good to have patients who walk away feeling they have not been heard, and that psychiatry is too complicated to put every patient into a med-check slot, regardless of what they require. But I believe that the term “racket” is reserved for fee-for-service practices where the physician makes more money by seeing more patients. I don’t believe it’s a term that anyone would apply to an over-taxed, under-funded setting where the doctor is paid a set salary (often well below private practice rates), regardless of how many, or how few, patients s/he sees.

The issues for private practice are different from those of clinics or prisons. In an outpatient practice, the psychiatrist often does not have an easy means to communicate with the psychotherapist. It requires obtaining and transmitting a release form, then taking time to call the therapist or to send notes. Care may be fragmented. In a clinic setting, while the psychiatrist does not do the psychotherapy, a single chart is shared among team members – including the psychiatrists, psychotherapists, nurses (to give depot injections, check vital sign, and do psychotherapy), and case managers. The therapists and case managers are often in communication with residential care providers and day program personnel, and they are able to relay pertinent information to the psychiatrist.

In the Community Psychiatry Program at Johns Hopkins, the therapist attends the routine 90 day review visits with the psychiatrist and patient in the same room.

In addition to issues related to communications and information exchange, clinic/prison care is often provided at little or no cost to the patient, and the psychiatrist is salaried. In Maryland, state regulators require that patients in publicly funded Outpatient Mental Health Centers be seen every 90 days, and psychiatrists don’t have the leeway to either recommend or accommodate a less frequent schedule. Patients may well be aware that the system is overtaxed, and the décor at every clinic I have worked at leaves no one doubting that finances are tight.

Still, I am perplexed by the ratio of 1 psychiatrist to 1,400 patients. The expectation at every clinic I have worked in has been that a full-time (40 hour/week) psychiatrist is responsible for the care of roughly 300 patients.

Certainly, this reflects life in a major city, one with two large psychiatric training programs, where it is possible to recruit physicians. There are areas of the country where the supply of psychiatrists simply does not meet the demand, and the available psychiatrists should be lauded for providing the care that no one else wants to give, even if it means they are stretched too thin. If, however, the clinic setting is unable to attract psychiatrists because the salaries being offered are not commensurate with what other area psychiatrists earn, then the system (not the doctor) should be criticized for expecting one doctor to care for 1,400 patients.

So the evil med check racket: It seems it’s a way not only for insurance companies to minimize their expenses and to leave at least some patients feeling unheard, but also to divide us as a profession when it comes to appreciating what we each do.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

DR. MILLER is the author of two new novels, Home Inspection and Double Billing and she is the co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work.

A reader from Carlisle, Pa., writes:

If Dr. Miller has ever practiced in a community mental health setting, she gives no evidence of it in her article. The title itself being offensive, the suggestion that “the economics might be clear” eludes me. The economics are not at all clear to me.

I am employed (and therefore have no personal stake in the fee schedule whatsoever) by a community mental health center that serves two counties in south-central Pennsylvania. My practice includes, I am told, about 1,400 patients, the vast majority of them without insurance other than Medicaid and/or Medicare. Many of these patients have no coverage for prescription medications, or have a carrier whose formulary is so restrictive as to require many hours of a nurse’s time to "prior auth" a mainstream medication, or to beg the drug rep for samples.

So, 1,400 patients, 40-hour/week work schedule: You do the math. The med-check “racket” here provides service for patients to which they would not otherwise have access.

The reader was offended by my post “The Med Check Racket,” which appeared on this blog in July, and in the August print edition of Clinical Psychiatry News. He is in good company; my article was so offensive to Dr. Anne Hanson, my co-blogger/author and good friend, that she responded the following week with her own post titled, “Those Evil Med Checks,” where she talks about her clinical work in the prisons. If you haven’t read it, please do.

I have worked at a number of community mental health centers. When I finished residency, I worked half-time at a CMHC, while I simultaneously began a private practice. I left that job to become medical director of a different CMHC, a position that enabled me to learn about the finances of public mental health clinics.

Since 1998, I have consulted part-time to the Johns Hopkins Community Psychiatry Program, and for a few years, I volunteered for HealthCare for the Homeless. I do know at least a little about community psychiatry.

“The Med Check Racket” was titled by a friend who complained to me about a private practice psychiatrist who sees him for 15 minutes every 6 months and asks a few, checklist-style, questions. I borrowed his comment as a title because I thought it was provocative, but I did not intend it to be offensive. Obviously, I was wrong!

I still believe that it does our profession no good to have patients who walk away feeling they have not been heard, and that psychiatry is too complicated to put every patient into a med-check slot, regardless of what they require. But I believe that the term “racket” is reserved for fee-for-service practices where the physician makes more money by seeing more patients. I don’t believe it’s a term that anyone would apply to an over-taxed, under-funded setting where the doctor is paid a set salary (often well below private practice rates), regardless of how many, or how few, patients s/he sees.

The issues for private practice are different from those of clinics or prisons. In an outpatient practice, the psychiatrist often does not have an easy means to communicate with the psychotherapist. It requires obtaining and transmitting a release form, then taking time to call the therapist or to send notes. Care may be fragmented. In a clinic setting, while the psychiatrist does not do the psychotherapy, a single chart is shared among team members – including the psychiatrists, psychotherapists, nurses (to give depot injections, check vital sign, and do psychotherapy), and case managers. The therapists and case managers are often in communication with residential care providers and day program personnel, and they are able to relay pertinent information to the psychiatrist.

In the Community Psychiatry Program at Johns Hopkins, the therapist attends the routine 90 day review visits with the psychiatrist and patient in the same room.

In addition to issues related to communications and information exchange, clinic/prison care is often provided at little or no cost to the patient, and the psychiatrist is salaried. In Maryland, state regulators require that patients in publicly funded Outpatient Mental Health Centers be seen every 90 days, and psychiatrists don’t have the leeway to either recommend or accommodate a less frequent schedule. Patients may well be aware that the system is overtaxed, and the décor at every clinic I have worked at leaves no one doubting that finances are tight.

Still, I am perplexed by the ratio of 1 psychiatrist to 1,400 patients. The expectation at every clinic I have worked in has been that a full-time (40 hour/week) psychiatrist is responsible for the care of roughly 300 patients.

Certainly, this reflects life in a major city, one with two large psychiatric training programs, where it is possible to recruit physicians. There are areas of the country where the supply of psychiatrists simply does not meet the demand, and the available psychiatrists should be lauded for providing the care that no one else wants to give, even if it means they are stretched too thin. If, however, the clinic setting is unable to attract psychiatrists because the salaries being offered are not commensurate with what other area psychiatrists earn, then the system (not the doctor) should be criticized for expecting one doctor to care for 1,400 patients.

So the evil med check racket: It seems it’s a way not only for insurance companies to minimize their expenses and to leave at least some patients feeling unheard, but also to divide us as a profession when it comes to appreciating what we each do.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

DR. MILLER is the author of two new novels, Home Inspection and Double Billing and she is the co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work.

A reader from Carlisle, Pa., writes:

If Dr. Miller has ever practiced in a community mental health setting, she gives no evidence of it in her article. The title itself being offensive, the suggestion that “the economics might be clear” eludes me. The economics are not at all clear to me.

I am employed (and therefore have no personal stake in the fee schedule whatsoever) by a community mental health center that serves two counties in south-central Pennsylvania. My practice includes, I am told, about 1,400 patients, the vast majority of them without insurance other than Medicaid and/or Medicare. Many of these patients have no coverage for prescription medications, or have a carrier whose formulary is so restrictive as to require many hours of a nurse’s time to "prior auth" a mainstream medication, or to beg the drug rep for samples.

So, 1,400 patients, 40-hour/week work schedule: You do the math. The med-check “racket” here provides service for patients to which they would not otherwise have access.

The reader was offended by my post “The Med Check Racket,” which appeared on this blog in July, and in the August print edition of Clinical Psychiatry News. He is in good company; my article was so offensive to Dr. Anne Hanson, my co-blogger/author and good friend, that she responded the following week with her own post titled, “Those Evil Med Checks,” where she talks about her clinical work in the prisons. If you haven’t read it, please do.

I have worked at a number of community mental health centers. When I finished residency, I worked half-time at a CMHC, while I simultaneously began a private practice. I left that job to become medical director of a different CMHC, a position that enabled me to learn about the finances of public mental health clinics.

Since 1998, I have consulted part-time to the Johns Hopkins Community Psychiatry Program, and for a few years, I volunteered for HealthCare for the Homeless. I do know at least a little about community psychiatry.

“The Med Check Racket” was titled by a friend who complained to me about a private practice psychiatrist who sees him for 15 minutes every 6 months and asks a few, checklist-style, questions. I borrowed his comment as a title because I thought it was provocative, but I did not intend it to be offensive. Obviously, I was wrong!

I still believe that it does our profession no good to have patients who walk away feeling they have not been heard, and that psychiatry is too complicated to put every patient into a med-check slot, regardless of what they require. But I believe that the term “racket” is reserved for fee-for-service practices where the physician makes more money by seeing more patients. I don’t believe it’s a term that anyone would apply to an over-taxed, under-funded setting where the doctor is paid a set salary (often well below private practice rates), regardless of how many, or how few, patients s/he sees.

The issues for private practice are different from those of clinics or prisons. In an outpatient practice, the psychiatrist often does not have an easy means to communicate with the psychotherapist. It requires obtaining and transmitting a release form, then taking time to call the therapist or to send notes. Care may be fragmented. In a clinic setting, while the psychiatrist does not do the psychotherapy, a single chart is shared among team members – including the psychiatrists, psychotherapists, nurses (to give depot injections, check vital sign, and do psychotherapy), and case managers. The therapists and case managers are often in communication with residential care providers and day program personnel, and they are able to relay pertinent information to the psychiatrist.

In the Community Psychiatry Program at Johns Hopkins, the therapist attends the routine 90 day review visits with the psychiatrist and patient in the same room.

In addition to issues related to communications and information exchange, clinic/prison care is often provided at little or no cost to the patient, and the psychiatrist is salaried. In Maryland, state regulators require that patients in publicly funded Outpatient Mental Health Centers be seen every 90 days, and psychiatrists don’t have the leeway to either recommend or accommodate a less frequent schedule. Patients may well be aware that the system is overtaxed, and the décor at every clinic I have worked at leaves no one doubting that finances are tight.

Still, I am perplexed by the ratio of 1 psychiatrist to 1,400 patients. The expectation at every clinic I have worked in has been that a full-time (40 hour/week) psychiatrist is responsible for the care of roughly 300 patients.

Certainly, this reflects life in a major city, one with two large psychiatric training programs, where it is possible to recruit physicians. There are areas of the country where the supply of psychiatrists simply does not meet the demand, and the available psychiatrists should be lauded for providing the care that no one else wants to give, even if it means they are stretched too thin. If, however, the clinic setting is unable to attract psychiatrists because the salaries being offered are not commensurate with what other area psychiatrists earn, then the system (not the doctor) should be criticized for expecting one doctor to care for 1,400 patients.

So the evil med check racket: It seems it’s a way not only for insurance companies to minimize their expenses and to leave at least some patients feeling unheard, but also to divide us as a profession when it comes to appreciating what we each do.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

DR. MILLER is the author of two new novels, Home Inspection and Double Billing and she is the co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work.

This Funny Thing We Call Privacy

When I go to the dentist, I sign in at the window, check off box that says I haven’t moved or changed insurance, and then have a seat in the waiting room with the other patients and a large tank of colorful fish. A secretary takes the sign-in sheet, in a HIPAA-compliant fashion, blacks out my name with a Sharpee. This is, I’m told, good. If you’re not another patient in the waiting room, a colorful fish, a dentist, hygenicist, or office staff at this large practice, and if you don’t happen to see my name posted on the schedule on the wall in the treatroom, then no one has to know that I get my teeth cleaned. I’m all for privacy in medical care.

The same issues come up in psychiatry, and all of medicine for that matter. The government mandates all types of procedures that protect patient privacy, and these procedures take time, effort, and money. Since I value privacy for medical treatment, I should be happy, but instead, I find many of the privacy regulations to be burdensome, and they create this odd state of perception of privacy when the reality remains that the privacy of medical treatment is compromised.

It’s regulated that sign-in sheets compromise privacy, but there remains the risk that patients might see each other in the waiting room. Perhaps every patient should have a mini-cubicle with black curtains to sit in? To protect privacy, when I sign in to my clinic’s electronic medical record and its e-prescribing program, both programs automatically sign me out every few minutes, a minor annoyance, but one of many.

The electronic medical record provides many conveniences, especially since psychiatric outpatient records have not yet been incorporated into them. I can access labs, read notes by other physicians, and I don’t have to spend time entering sensitive psychiatric information, except for medications. Given that psychiatric records have extra protections, can a patient elect to not to tell another physician that they see a psychiatrist? Well, not really, because the medications get entered into the record, it is recorded that the patient had an appointment with psychiatry, and patients often tell their primary care doctors that they are treated by a psychiatrist, so their diagnoses and medications are recorded by those doctors in their notes.

If patients are not comfortable telling their dermatologist that they have been treated for bipolar disorder, or had three abortions, they lose that option. Perhaps it’s not all bad – their lithium could be making their skin condition worse, and patients don’t always know which information it is important to share. But it may also be true that a physician may ascribe patients’ symptoms to their psychiatric condition and not evaluate them with the same diligence they would if a psychiatric condition were not revealed. (Does this still happen? That’s it’s own blog post, but see Discrimination Against Patients with a Psychiatric History for another medical blogger’s insights on this.)

So our illusion of privacy goes one step further with electronic records. In the institution where I work, I believe (and I could be wrong about the number) that approximately 9,000 people have access to the records. There are checks on the system to determine that those accessing have valid reason, but those checks are random, and the major impediment to obliging curiosity and looking at the records of a friend, neighbor, colleague, or ex-girlfriend, remains the fear of being discovered and the serious repercussions that would occur.

In Maryland, our state legislature has spent years debating whether the state’s Board of Physicians should be able to look at patient records if a third party lodges a complaint against a doctor and patients do not want their records released. Yet, hospital regulators regularly review psychiatric charts to determine if they are in compliance for accreditation purposes, without getting the patient’s authorization first. And insurance companies access patient records with patient authorization, then often use this information to deny coverage, but is it really “authorization” (a valid form of consent) if desperately ill patients are told they won’t be treated if they don’t sign?

So we shred. We pay for secure portals for email. We follow rules regarding secured, HIPAA-compliant fax locations. We sign in and out of the various computer screens every 7 minutes to make sure no unauthorized soul sneaks in and reads when we aren’t looking. Our government pays physicians to install EMRs with the promise that this will make medicine better. We refuse to speak with families and with physicians outside our system without signed releases, even if doing so delays care or creates inconvenience. All patients sign off that they were offered privacy notices.

Our patients see all this, and it leads them to believe that confidentiality laws make their treatment more private, that the system has many safeguards, and that only the fish know they are getting their teeth cleaned. I can’t help but think it would be so nice if there were a little less in the way of regulation and requirements and a little more attention to the best interest and privacy needs of the individual patient.

—Dinah Miller, M.D.

DR. MILLER is the author of two new novels, Home Inspection and Double Billing and she is the co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work.

When I go to the dentist, I sign in at the window, check off box that says I haven’t moved or changed insurance, and then have a seat in the waiting room with the other patients and a large tank of colorful fish. A secretary takes the sign-in sheet, in a HIPAA-compliant fashion, blacks out my name with a Sharpee. This is, I’m told, good. If you’re not another patient in the waiting room, a colorful fish, a dentist, hygenicist, or office staff at this large practice, and if you don’t happen to see my name posted on the schedule on the wall in the treatroom, then no one has to know that I get my teeth cleaned. I’m all for privacy in medical care.

The same issues come up in psychiatry, and all of medicine for that matter. The government mandates all types of procedures that protect patient privacy, and these procedures take time, effort, and money. Since I value privacy for medical treatment, I should be happy, but instead, I find many of the privacy regulations to be burdensome, and they create this odd state of perception of privacy when the reality remains that the privacy of medical treatment is compromised.

It’s regulated that sign-in sheets compromise privacy, but there remains the risk that patients might see each other in the waiting room. Perhaps every patient should have a mini-cubicle with black curtains to sit in? To protect privacy, when I sign in to my clinic’s electronic medical record and its e-prescribing program, both programs automatically sign me out every few minutes, a minor annoyance, but one of many.

The electronic medical record provides many conveniences, especially since psychiatric outpatient records have not yet been incorporated into them. I can access labs, read notes by other physicians, and I don’t have to spend time entering sensitive psychiatric information, except for medications. Given that psychiatric records have extra protections, can a patient elect to not to tell another physician that they see a psychiatrist? Well, not really, because the medications get entered into the record, it is recorded that the patient had an appointment with psychiatry, and patients often tell their primary care doctors that they are treated by a psychiatrist, so their diagnoses and medications are recorded by those doctors in their notes.

If patients are not comfortable telling their dermatologist that they have been treated for bipolar disorder, or had three abortions, they lose that option. Perhaps it’s not all bad – their lithium could be making their skin condition worse, and patients don’t always know which information it is important to share. But it may also be true that a physician may ascribe patients’ symptoms to their psychiatric condition and not evaluate them with the same diligence they would if a psychiatric condition were not revealed. (Does this still happen? That’s it’s own blog post, but see Discrimination Against Patients with a Psychiatric History for another medical blogger’s insights on this.)

So our illusion of privacy goes one step further with electronic records. In the institution where I work, I believe (and I could be wrong about the number) that approximately 9,000 people have access to the records. There are checks on the system to determine that those accessing have valid reason, but those checks are random, and the major impediment to obliging curiosity and looking at the records of a friend, neighbor, colleague, or ex-girlfriend, remains the fear of being discovered and the serious repercussions that would occur.