User login

We’ve been hearing a lot about health care integration lately, particularly around integration of behavioral health care with physical health care. (This term behavioral health can have several meanings; it is most often used to refer to “mental health plus substance use” disorders, which is how I am using it here.)

Since before Descartes, we have disintegrated man and woman into head and torso; brain and body; mind and soul. Only in the past hundred years have we begun the discussion about bringing these parts together again; reintegrating the psyche and the soma; integrating behavioral health and physical health.

The state of Maryland began this process last year, as its Department of Health and Mental Hygiene initiated discussions about merging the “Health” with the “Hygiene.” (As if cleanliness would make the difference.) For the past several months, stakeholders interested in the rights and well-being of people with mental health and addiction problems have been meeting, sometimes several times per week, with state and Medicaid officials, insurance representatives, advocacy organizations, and clinicians, to hash out what the new integrated Medicaid should look like. MCOs, ASOs, MBHOs, and ACOs are spit out like bullets, depending on your position about which organizational model is best able to balance enrollees' health with the applicable cost.

The Maryland Mental Health Coalition, an association of behavioral health providers and advocacy organizations, has been organizing an impressive effort, orchestrated by Linda Raines, who is also executive director of the Maryland chapter of Mental Health America (MHA), to unite our disparate voices into one. They are all mostly in agreement except for two main areas: splitting populations into more and less severe subgroups and the timing of integration of physical health into behavioral health.

Some believe that the populations of people with behavioral health problems should be split into those who are less severe and only receiving care from a primary care physician (PCP) and those who are more severely ill and receiving help from specialty mental health providers. The more ill ones, often with severe and chronic mental illness, consume the most resources, both in time and in money. But they are only 10-15% of the entire population of people with any behavioral health problem. The other 85-90% would receive a seemingly less integrated form of care, called collaborative care, which recognizes the fact that the supply of mental health providers is not enough to meet the demand for the entire population.

Collaborative care, which has had somewhat positive to mixed results with respect to outcomes, uses psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health providers to review a patient’s electronic health record and discuss the patient’s problems and needs in a collaborative format that provides clinical decision support to the primary care clinician who is primarily managing the care. This is often telephonic and web-based support, though some provide support that is co-located with the PCPs.

The other part of the discussion is the degree to which the behavioral health care should be carved out versus provided by the parent managed care organization. The American Psychiatric Association has a position statement opposing the concept of carve-outs. The paper suggests that:

“Mental health and substance abuse integration occurs when benefits and services for people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders are integrated, funded and administered no differently than for those people with other medical/surgical illnesses.”

The Maryland Psychiatric Society is also pushing on this point, suggesting that “financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. ” The Maryland chapter of MHA and most of the Coalition members feel that an Administrative Services Organization (ASO) model that uses a behavioral health home for people with severe illnesses, and a collaborative care model for the other 85%, will be the best balance. I liken this to how people like their band-aids torn off – with a sudden amount of pain that subsides quickly, or a drawn-out but consistent level of pain for a longer period of time. It’s a personal choice.

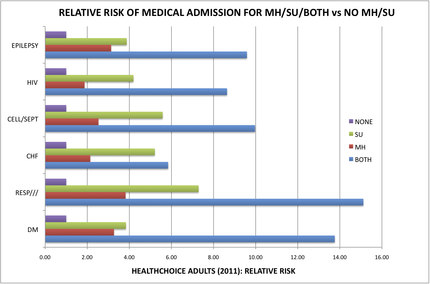

Ask the people who have both a medical problem as well as a behavioral health problem. People with both mental health and addiction illnesses in Maryland Medicaid are 8-15 times more likely to be medically hospitalized for problems like diabetes, epilepsy, infections, and heart failure, than those who do not have a behavioral health condition [See chart below]. Wow! That disparity is impressive.

What model will best reduce this disparity the quickest?

Of course, I am a member of MPS and have a bias in my view of this situation (reader beware). But the entire behavioral health advocacy community is coming together to recommend what it thinks is the best financial and administrative framework within which to provide the greatest good. We need to decide, by the end of September, which infrastructure model to use in order to provide more “integrated” health care.

Will it apply equally, regardless of illness severity?

Will it incorporate both somatic health and behavioral health, connecting the brain and the body again? Or will it keep them separate but equal?

Keep track at http://bit.ly/Ouptue.

The data provided by the Maryland’s Integration Data Work Group [The chart is based on this data] clearly and profoundly demonstrate this disparity in chronic medical problems among the 200,000 or so HealthChoice enrollees. People identified as having a mental health illness are medically admitted 2 to 4 times more often for diabetes, heart failure, infections, epilepsy, and pulmonary disease than are people without any behavioral health condition. People identified as having a substance use disorder are medically admitted 4 to 7 times more often than people without any behavioral health condition. And, for people who have both mental health and substance use illness, these people are admitted 8- to 15-times more often than those without.

We estimated the cost for hospitalization for these six medical categories alone, and only for the 19-64 year old age group that we analyzed, to be about $86 million in excess costs over and above what would be expected for people without a behavioral health illness. A full analysis of this data would likely demonstrate more than $150 million in excess costs, much of which is avoidable with improved outpatient care.

The MPS believes that a model that is most likely to adopt a culture of integration is also the one that will most likely reduce these avoidable costs and improve the health care of this population. It is clear that some of the proposed models are more or less likely to deliver a culture of integration and innovation. The Maryland Psychiatric Society believes that Maryland should ensure that the chosen model is hard-wired to contain the following features:

1. Financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. If the ASO denies a service and this results in an $80,000 bill to the MCO for hospitalization after a suicide attempt, the ASO should be at risk for part of this bill. Similarly, if the MBHO provides case management services that results in improved diabetes care management that leads to reduced hospitalization costs for the MCO, the MBHO should share in those savings. There should be no opportunities for one payor to point to the other payor and say “not me.”

2. Financial rewards and penalties for the clinicians should be integrated such that they are incentivized to pay attention to both somatic and behavioral health (BH) needs. This may include case management services that help behavioral health clinicians coordinate with somatic clinicians and services, as well as collaborative BH services that coordinate with PCPs.

3. Minimize administrative overhead such that the maximum proportion of expenditures are spent on direct care and coordination of services.

4. The spirit and letter of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act should be proactively maintained. (There is a risk that a State-run ASO would be able to skirt the United States’s federal Mental Health Parity law, thus being able to provide less costly care to those with behavioral health problems than those with traditional MCO coverage. The Mental Health Parity law applies to Managed Care Organizations, not to states.) The payor must “provide a detailed analysis demonstrating that their utilization management protocols do not have more restrictive nonquantitative treatment limitations compared to those used on the somatic side. The term “protocol” includes “…any processes, strategies, evidentiary standards, or other factors used in applying the nonquantitative treatment limitation to mental health or substance use disorder benefits.”

5. If the organization delegates any of its responsibilities to another contracted organization, it must “specify that the contractor shall comply with, and maintain parity between the MH/SUD benefits it administers and the organization's medical/surgical benefits pursuant to the applicable federal and/or state law or regulation and any binding regulatory or subregulatory guidance related thereto.”

6. Descriptions of the processes that the organization uses to ensure compliance with regulatory health care parity requirements, including regulations pertaining to mental health and/or substance usage disorders (MHPAEA), including:

a. Periodic internal monitoring and auditing of compliance;

b. Periodic review and analysis to determine if there are any changes in its benefits, policies and procedures, and utilization management protocols that impact compliance.

c. Periodic communication to delegated contractors regarding changes impacting compliance, including parity of health care services such as mental health and/or substance use disorder parity (MHPAEA).

7. A comprehensive list of services and procedures that support integrated and comprehensive recovery models must be available to clinicians and consumers.

8. Integration must include all levels and aspects of care – emergency departments; all inpatient hospital care; partial hospitalization; nursing homes; assisted living facilities; group homes, residential programs; day programs; outpatient care; diversion programs; pharmacy, including all medications; and all types of care including mental health, somatic and addiction care.

9. Either require coordination of clinical information via the state-designated HIE or provision of a shared electronic health record service for all integrated care, with appropriate provisions to protect patient privacy.

10. Financial, administrative, and clinical data collection systems must be integrated to permit analysis of expenditures associated with patient outcomes.

11. Consumers should be allowed to receive services from any willing clinician.

12. The comprehensive list of services that patients may receive must be developed using a recovery-based model and covered under the integration of services.

13. Data transparency for all stakeholders is critical for trust and success.

14. An oversight group of stakeholders will monthly review integrated data from all payor sources (MCO, ASO, MBHO, etc) and service utilization sources (ADT, Pharmacy, etc) for the purposes of ongoing review and ensuring coordination of care.

15. Spreadsheets must be developed that permit ongoing ability for stakeholders to view levels of care being provided and denied, as well as their outcomes, for all patient subpopulations at the granular level.

16. Standards should be developed for network provider directories that ensure accurate and up-to-date contact information as well as the ability to indicate if a provider is able to accept new outpatients in a timely manner.

An interesting approach that could merge these ideas is to develop an MCO that is led by people with expertise in managing the health of people with behavioral health conditions. This would be a pretty new animal, one that is savvy to the needs of both behavioral health and primary care and that can effectively incentivize health system behaviors that improve overall health while reducing total costs.

There could also be a role for Maryland’s two large medical systems, University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins, to work together in running such a hybrid animal. With the goal of getting this up and running by 2014, time may be the most limiting factor here, potentially resulting in us going down more familiar, if less effective, pathways.

What is going on in your state? Is there a challenge to integrate care? Which populations? Is somatic care included? Let us know what is going on in your state.

—Steven Roy Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.

We’ve been hearing a lot about health care integration lately, particularly around integration of behavioral health care with physical health care. (This term behavioral health can have several meanings; it is most often used to refer to “mental health plus substance use” disorders, which is how I am using it here.)

Since before Descartes, we have disintegrated man and woman into head and torso; brain and body; mind and soul. Only in the past hundred years have we begun the discussion about bringing these parts together again; reintegrating the psyche and the soma; integrating behavioral health and physical health.

The state of Maryland began this process last year, as its Department of Health and Mental Hygiene initiated discussions about merging the “Health” with the “Hygiene.” (As if cleanliness would make the difference.) For the past several months, stakeholders interested in the rights and well-being of people with mental health and addiction problems have been meeting, sometimes several times per week, with state and Medicaid officials, insurance representatives, advocacy organizations, and clinicians, to hash out what the new integrated Medicaid should look like. MCOs, ASOs, MBHOs, and ACOs are spit out like bullets, depending on your position about which organizational model is best able to balance enrollees' health with the applicable cost.

The Maryland Mental Health Coalition, an association of behavioral health providers and advocacy organizations, has been organizing an impressive effort, orchestrated by Linda Raines, who is also executive director of the Maryland chapter of Mental Health America (MHA), to unite our disparate voices into one. They are all mostly in agreement except for two main areas: splitting populations into more and less severe subgroups and the timing of integration of physical health into behavioral health.

Some believe that the populations of people with behavioral health problems should be split into those who are less severe and only receiving care from a primary care physician (PCP) and those who are more severely ill and receiving help from specialty mental health providers. The more ill ones, often with severe and chronic mental illness, consume the most resources, both in time and in money. But they are only 10-15% of the entire population of people with any behavioral health problem. The other 85-90% would receive a seemingly less integrated form of care, called collaborative care, which recognizes the fact that the supply of mental health providers is not enough to meet the demand for the entire population.

Collaborative care, which has had somewhat positive to mixed results with respect to outcomes, uses psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health providers to review a patient’s electronic health record and discuss the patient’s problems and needs in a collaborative format that provides clinical decision support to the primary care clinician who is primarily managing the care. This is often telephonic and web-based support, though some provide support that is co-located with the PCPs.

The other part of the discussion is the degree to which the behavioral health care should be carved out versus provided by the parent managed care organization. The American Psychiatric Association has a position statement opposing the concept of carve-outs. The paper suggests that:

“Mental health and substance abuse integration occurs when benefits and services for people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders are integrated, funded and administered no differently than for those people with other medical/surgical illnesses.”

The Maryland Psychiatric Society is also pushing on this point, suggesting that “financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. ” The Maryland chapter of MHA and most of the Coalition members feel that an Administrative Services Organization (ASO) model that uses a behavioral health home for people with severe illnesses, and a collaborative care model for the other 85%, will be the best balance. I liken this to how people like their band-aids torn off – with a sudden amount of pain that subsides quickly, or a drawn-out but consistent level of pain for a longer period of time. It’s a personal choice.

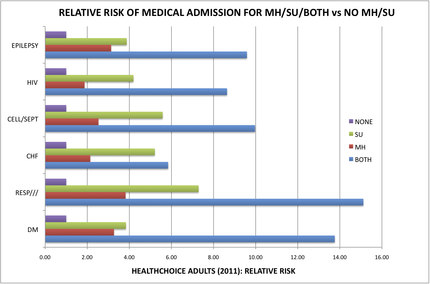

Ask the people who have both a medical problem as well as a behavioral health problem. People with both mental health and addiction illnesses in Maryland Medicaid are 8-15 times more likely to be medically hospitalized for problems like diabetes, epilepsy, infections, and heart failure, than those who do not have a behavioral health condition [See chart below]. Wow! That disparity is impressive.

What model will best reduce this disparity the quickest?

Of course, I am a member of MPS and have a bias in my view of this situation (reader beware). But the entire behavioral health advocacy community is coming together to recommend what it thinks is the best financial and administrative framework within which to provide the greatest good. We need to decide, by the end of September, which infrastructure model to use in order to provide more “integrated” health care.

Will it apply equally, regardless of illness severity?

Will it incorporate both somatic health and behavioral health, connecting the brain and the body again? Or will it keep them separate but equal?

Keep track at http://bit.ly/Ouptue.

The data provided by the Maryland’s Integration Data Work Group [The chart is based on this data] clearly and profoundly demonstrate this disparity in chronic medical problems among the 200,000 or so HealthChoice enrollees. People identified as having a mental health illness are medically admitted 2 to 4 times more often for diabetes, heart failure, infections, epilepsy, and pulmonary disease than are people without any behavioral health condition. People identified as having a substance use disorder are medically admitted 4 to 7 times more often than people without any behavioral health condition. And, for people who have both mental health and substance use illness, these people are admitted 8- to 15-times more often than those without.

We estimated the cost for hospitalization for these six medical categories alone, and only for the 19-64 year old age group that we analyzed, to be about $86 million in excess costs over and above what would be expected for people without a behavioral health illness. A full analysis of this data would likely demonstrate more than $150 million in excess costs, much of which is avoidable with improved outpatient care.

The MPS believes that a model that is most likely to adopt a culture of integration is also the one that will most likely reduce these avoidable costs and improve the health care of this population. It is clear that some of the proposed models are more or less likely to deliver a culture of integration and innovation. The Maryland Psychiatric Society believes that Maryland should ensure that the chosen model is hard-wired to contain the following features:

1. Financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. If the ASO denies a service and this results in an $80,000 bill to the MCO for hospitalization after a suicide attempt, the ASO should be at risk for part of this bill. Similarly, if the MBHO provides case management services that results in improved diabetes care management that leads to reduced hospitalization costs for the MCO, the MBHO should share in those savings. There should be no opportunities for one payor to point to the other payor and say “not me.”

2. Financial rewards and penalties for the clinicians should be integrated such that they are incentivized to pay attention to both somatic and behavioral health (BH) needs. This may include case management services that help behavioral health clinicians coordinate with somatic clinicians and services, as well as collaborative BH services that coordinate with PCPs.

3. Minimize administrative overhead such that the maximum proportion of expenditures are spent on direct care and coordination of services.

4. The spirit and letter of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act should be proactively maintained. (There is a risk that a State-run ASO would be able to skirt the United States’s federal Mental Health Parity law, thus being able to provide less costly care to those with behavioral health problems than those with traditional MCO coverage. The Mental Health Parity law applies to Managed Care Organizations, not to states.) The payor must “provide a detailed analysis demonstrating that their utilization management protocols do not have more restrictive nonquantitative treatment limitations compared to those used on the somatic side. The term “protocol” includes “…any processes, strategies, evidentiary standards, or other factors used in applying the nonquantitative treatment limitation to mental health or substance use disorder benefits.”

5. If the organization delegates any of its responsibilities to another contracted organization, it must “specify that the contractor shall comply with, and maintain parity between the MH/SUD benefits it administers and the organization's medical/surgical benefits pursuant to the applicable federal and/or state law or regulation and any binding regulatory or subregulatory guidance related thereto.”

6. Descriptions of the processes that the organization uses to ensure compliance with regulatory health care parity requirements, including regulations pertaining to mental health and/or substance usage disorders (MHPAEA), including:

a. Periodic internal monitoring and auditing of compliance;

b. Periodic review and analysis to determine if there are any changes in its benefits, policies and procedures, and utilization management protocols that impact compliance.

c. Periodic communication to delegated contractors regarding changes impacting compliance, including parity of health care services such as mental health and/or substance use disorder parity (MHPAEA).

7. A comprehensive list of services and procedures that support integrated and comprehensive recovery models must be available to clinicians and consumers.

8. Integration must include all levels and aspects of care – emergency departments; all inpatient hospital care; partial hospitalization; nursing homes; assisted living facilities; group homes, residential programs; day programs; outpatient care; diversion programs; pharmacy, including all medications; and all types of care including mental health, somatic and addiction care.

9. Either require coordination of clinical information via the state-designated HIE or provision of a shared electronic health record service for all integrated care, with appropriate provisions to protect patient privacy.

10. Financial, administrative, and clinical data collection systems must be integrated to permit analysis of expenditures associated with patient outcomes.

11. Consumers should be allowed to receive services from any willing clinician.

12. The comprehensive list of services that patients may receive must be developed using a recovery-based model and covered under the integration of services.

13. Data transparency for all stakeholders is critical for trust and success.

14. An oversight group of stakeholders will monthly review integrated data from all payor sources (MCO, ASO, MBHO, etc) and service utilization sources (ADT, Pharmacy, etc) for the purposes of ongoing review and ensuring coordination of care.

15. Spreadsheets must be developed that permit ongoing ability for stakeholders to view levels of care being provided and denied, as well as their outcomes, for all patient subpopulations at the granular level.

16. Standards should be developed for network provider directories that ensure accurate and up-to-date contact information as well as the ability to indicate if a provider is able to accept new outpatients in a timely manner.

An interesting approach that could merge these ideas is to develop an MCO that is led by people with expertise in managing the health of people with behavioral health conditions. This would be a pretty new animal, one that is savvy to the needs of both behavioral health and primary care and that can effectively incentivize health system behaviors that improve overall health while reducing total costs.

There could also be a role for Maryland’s two large medical systems, University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins, to work together in running such a hybrid animal. With the goal of getting this up and running by 2014, time may be the most limiting factor here, potentially resulting in us going down more familiar, if less effective, pathways.

What is going on in your state? Is there a challenge to integrate care? Which populations? Is somatic care included? Let us know what is going on in your state.

—Steven Roy Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.

We’ve been hearing a lot about health care integration lately, particularly around integration of behavioral health care with physical health care. (This term behavioral health can have several meanings; it is most often used to refer to “mental health plus substance use” disorders, which is how I am using it here.)

Since before Descartes, we have disintegrated man and woman into head and torso; brain and body; mind and soul. Only in the past hundred years have we begun the discussion about bringing these parts together again; reintegrating the psyche and the soma; integrating behavioral health and physical health.

The state of Maryland began this process last year, as its Department of Health and Mental Hygiene initiated discussions about merging the “Health” with the “Hygiene.” (As if cleanliness would make the difference.) For the past several months, stakeholders interested in the rights and well-being of people with mental health and addiction problems have been meeting, sometimes several times per week, with state and Medicaid officials, insurance representatives, advocacy organizations, and clinicians, to hash out what the new integrated Medicaid should look like. MCOs, ASOs, MBHOs, and ACOs are spit out like bullets, depending on your position about which organizational model is best able to balance enrollees' health with the applicable cost.

The Maryland Mental Health Coalition, an association of behavioral health providers and advocacy organizations, has been organizing an impressive effort, orchestrated by Linda Raines, who is also executive director of the Maryland chapter of Mental Health America (MHA), to unite our disparate voices into one. They are all mostly in agreement except for two main areas: splitting populations into more and less severe subgroups and the timing of integration of physical health into behavioral health.

Some believe that the populations of people with behavioral health problems should be split into those who are less severe and only receiving care from a primary care physician (PCP) and those who are more severely ill and receiving help from specialty mental health providers. The more ill ones, often with severe and chronic mental illness, consume the most resources, both in time and in money. But they are only 10-15% of the entire population of people with any behavioral health problem. The other 85-90% would receive a seemingly less integrated form of care, called collaborative care, which recognizes the fact that the supply of mental health providers is not enough to meet the demand for the entire population.

Collaborative care, which has had somewhat positive to mixed results with respect to outcomes, uses psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health providers to review a patient’s electronic health record and discuss the patient’s problems and needs in a collaborative format that provides clinical decision support to the primary care clinician who is primarily managing the care. This is often telephonic and web-based support, though some provide support that is co-located with the PCPs.

The other part of the discussion is the degree to which the behavioral health care should be carved out versus provided by the parent managed care organization. The American Psychiatric Association has a position statement opposing the concept of carve-outs. The paper suggests that:

“Mental health and substance abuse integration occurs when benefits and services for people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders are integrated, funded and administered no differently than for those people with other medical/surgical illnesses.”

The Maryland Psychiatric Society is also pushing on this point, suggesting that “financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. ” The Maryland chapter of MHA and most of the Coalition members feel that an Administrative Services Organization (ASO) model that uses a behavioral health home for people with severe illnesses, and a collaborative care model for the other 85%, will be the best balance. I liken this to how people like their band-aids torn off – with a sudden amount of pain that subsides quickly, or a drawn-out but consistent level of pain for a longer period of time. It’s a personal choice.

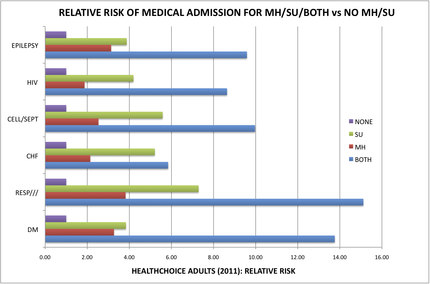

Ask the people who have both a medical problem as well as a behavioral health problem. People with both mental health and addiction illnesses in Maryland Medicaid are 8-15 times more likely to be medically hospitalized for problems like diabetes, epilepsy, infections, and heart failure, than those who do not have a behavioral health condition [See chart below]. Wow! That disparity is impressive.

What model will best reduce this disparity the quickest?

Of course, I am a member of MPS and have a bias in my view of this situation (reader beware). But the entire behavioral health advocacy community is coming together to recommend what it thinks is the best financial and administrative framework within which to provide the greatest good. We need to decide, by the end of September, which infrastructure model to use in order to provide more “integrated” health care.

Will it apply equally, regardless of illness severity?

Will it incorporate both somatic health and behavioral health, connecting the brain and the body again? Or will it keep them separate but equal?

Keep track at http://bit.ly/Ouptue.

The data provided by the Maryland’s Integration Data Work Group [The chart is based on this data] clearly and profoundly demonstrate this disparity in chronic medical problems among the 200,000 or so HealthChoice enrollees. People identified as having a mental health illness are medically admitted 2 to 4 times more often for diabetes, heart failure, infections, epilepsy, and pulmonary disease than are people without any behavioral health condition. People identified as having a substance use disorder are medically admitted 4 to 7 times more often than people without any behavioral health condition. And, for people who have both mental health and substance use illness, these people are admitted 8- to 15-times more often than those without.

We estimated the cost for hospitalization for these six medical categories alone, and only for the 19-64 year old age group that we analyzed, to be about $86 million in excess costs over and above what would be expected for people without a behavioral health illness. A full analysis of this data would likely demonstrate more than $150 million in excess costs, much of which is avoidable with improved outpatient care.

The MPS believes that a model that is most likely to adopt a culture of integration is also the one that will most likely reduce these avoidable costs and improve the health care of this population. It is clear that some of the proposed models are more or less likely to deliver a culture of integration and innovation. The Maryland Psychiatric Society believes that Maryland should ensure that the chosen model is hard-wired to contain the following features:

1. Financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. If the ASO denies a service and this results in an $80,000 bill to the MCO for hospitalization after a suicide attempt, the ASO should be at risk for part of this bill. Similarly, if the MBHO provides case management services that results in improved diabetes care management that leads to reduced hospitalization costs for the MCO, the MBHO should share in those savings. There should be no opportunities for one payor to point to the other payor and say “not me.”

2. Financial rewards and penalties for the clinicians should be integrated such that they are incentivized to pay attention to both somatic and behavioral health (BH) needs. This may include case management services that help behavioral health clinicians coordinate with somatic clinicians and services, as well as collaborative BH services that coordinate with PCPs.

3. Minimize administrative overhead such that the maximum proportion of expenditures are spent on direct care and coordination of services.

4. The spirit and letter of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act should be proactively maintained. (There is a risk that a State-run ASO would be able to skirt the United States’s federal Mental Health Parity law, thus being able to provide less costly care to those with behavioral health problems than those with traditional MCO coverage. The Mental Health Parity law applies to Managed Care Organizations, not to states.) The payor must “provide a detailed analysis demonstrating that their utilization management protocols do not have more restrictive nonquantitative treatment limitations compared to those used on the somatic side. The term “protocol” includes “…any processes, strategies, evidentiary standards, or other factors used in applying the nonquantitative treatment limitation to mental health or substance use disorder benefits.”

5. If the organization delegates any of its responsibilities to another contracted organization, it must “specify that the contractor shall comply with, and maintain parity between the MH/SUD benefits it administers and the organization's medical/surgical benefits pursuant to the applicable federal and/or state law or regulation and any binding regulatory or subregulatory guidance related thereto.”

6. Descriptions of the processes that the organization uses to ensure compliance with regulatory health care parity requirements, including regulations pertaining to mental health and/or substance usage disorders (MHPAEA), including:

a. Periodic internal monitoring and auditing of compliance;

b. Periodic review and analysis to determine if there are any changes in its benefits, policies and procedures, and utilization management protocols that impact compliance.

c. Periodic communication to delegated contractors regarding changes impacting compliance, including parity of health care services such as mental health and/or substance use disorder parity (MHPAEA).

7. A comprehensive list of services and procedures that support integrated and comprehensive recovery models must be available to clinicians and consumers.

8. Integration must include all levels and aspects of care – emergency departments; all inpatient hospital care; partial hospitalization; nursing homes; assisted living facilities; group homes, residential programs; day programs; outpatient care; diversion programs; pharmacy, including all medications; and all types of care including mental health, somatic and addiction care.

9. Either require coordination of clinical information via the state-designated HIE or provision of a shared electronic health record service for all integrated care, with appropriate provisions to protect patient privacy.

10. Financial, administrative, and clinical data collection systems must be integrated to permit analysis of expenditures associated with patient outcomes.

11. Consumers should be allowed to receive services from any willing clinician.

12. The comprehensive list of services that patients may receive must be developed using a recovery-based model and covered under the integration of services.

13. Data transparency for all stakeholders is critical for trust and success.

14. An oversight group of stakeholders will monthly review integrated data from all payor sources (MCO, ASO, MBHO, etc) and service utilization sources (ADT, Pharmacy, etc) for the purposes of ongoing review and ensuring coordination of care.

15. Spreadsheets must be developed that permit ongoing ability for stakeholders to view levels of care being provided and denied, as well as their outcomes, for all patient subpopulations at the granular level.

16. Standards should be developed for network provider directories that ensure accurate and up-to-date contact information as well as the ability to indicate if a provider is able to accept new outpatients in a timely manner.

An interesting approach that could merge these ideas is to develop an MCO that is led by people with expertise in managing the health of people with behavioral health conditions. This would be a pretty new animal, one that is savvy to the needs of both behavioral health and primary care and that can effectively incentivize health system behaviors that improve overall health while reducing total costs.

There could also be a role for Maryland’s two large medical systems, University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins, to work together in running such a hybrid animal. With the goal of getting this up and running by 2014, time may be the most limiting factor here, potentially resulting in us going down more familiar, if less effective, pathways.

What is going on in your state? Is there a challenge to integrate care? Which populations? Is somatic care included? Let us know what is going on in your state.

—Steven Roy Daviss, M.D., DFAPA

DR. DAVISS is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, policy wonk for the Maryland Psychiatric Society, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, and co-author of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. In addition to @HITshrink on Twitter, he can be found on the Shrink Rap blog.