User login

Waxy fingers and skin tethering

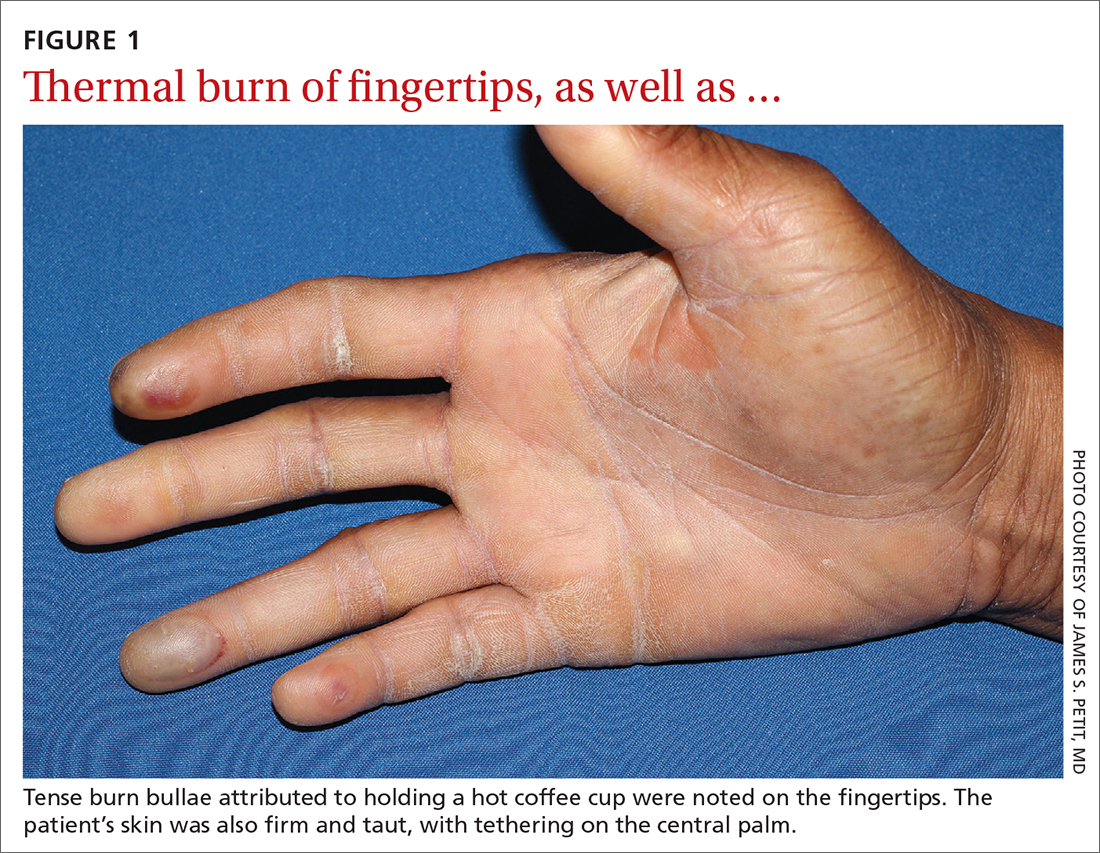

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

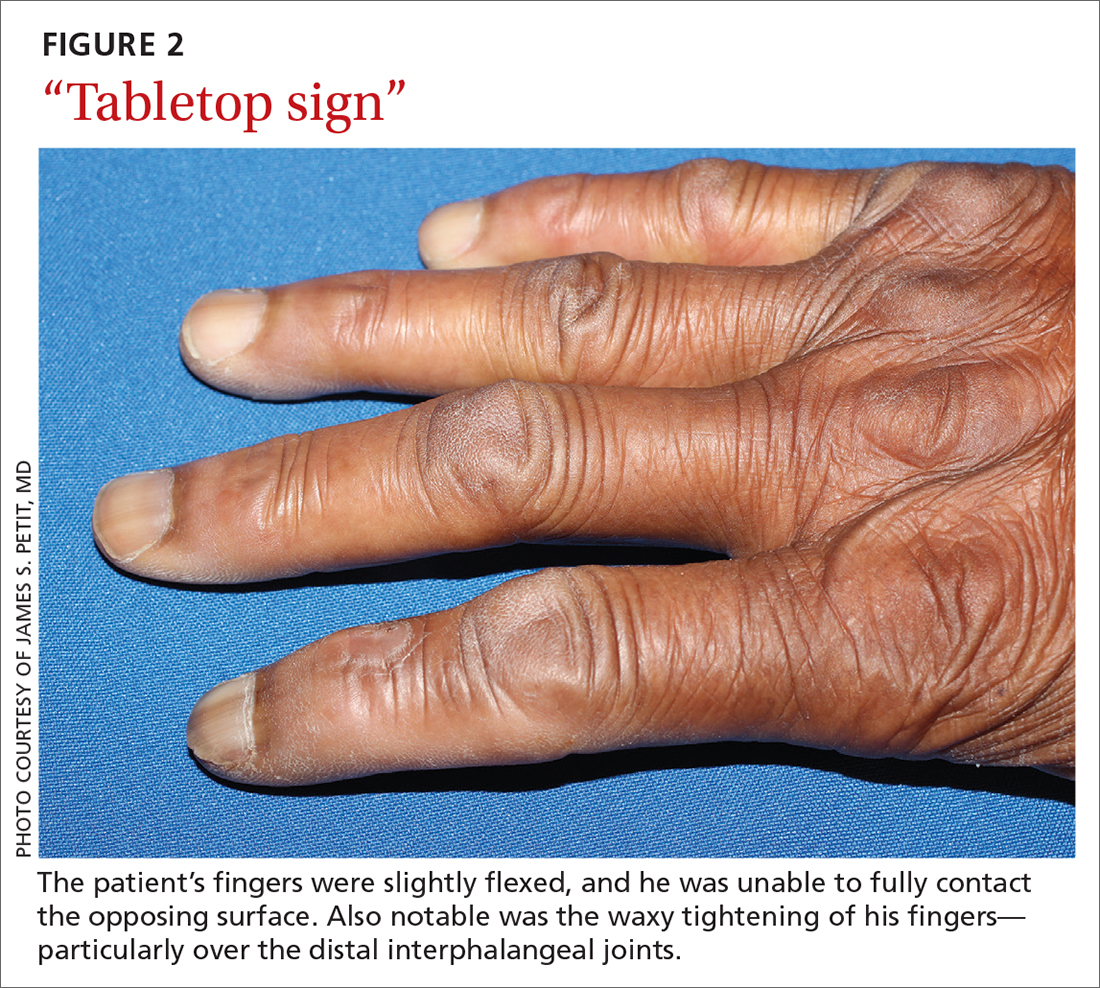

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

Bullae on elderly woman’s toes

A biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence; the results were negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to the diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum (BD). This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes.

The etiology of BD is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites.

A diagnosis of BD can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar diagnoses such as epidermolysis bullosa, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And, while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.1,2 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

The blisters associated with BD spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence. Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection. For this patient, the bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

This case was adapted from: Mims L, Savage A, Chessman A. Blisters on an elderly woman’s toes. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:273-274.

1. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

2. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01305.x

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. UpToDate. Updated July 30, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters

A biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence; the results were negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to the diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum (BD). This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes.

The etiology of BD is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites.

A diagnosis of BD can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar diagnoses such as epidermolysis bullosa, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And, while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.1,2 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

The blisters associated with BD spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence. Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection. For this patient, the bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

This case was adapted from: Mims L, Savage A, Chessman A. Blisters on an elderly woman’s toes. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:273-274.

A biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence; the results were negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to the diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum (BD). This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes.

The etiology of BD is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites.

A diagnosis of BD can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar diagnoses such as epidermolysis bullosa, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And, while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.1,2 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

The blisters associated with BD spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence. Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection. For this patient, the bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

This case was adapted from: Mims L, Savage A, Chessman A. Blisters on an elderly woman’s toes. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:273-274.

1. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

2. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01305.x

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. UpToDate. Updated July 30, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters

1. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

2. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01305.x

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. UpToDate. Updated July 30, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters

New wound over an old scar

While a squamous cell carcinoma presenting this way is perhaps more common, this nonhealing draining papule over a sternal scar was actually a sternocutaneous fistula (SCF). Examination revealed multiple bound down pits along the sternotomy scar. Very gentle probing of the papule in consideration of biopsy revealed a wire foreign body—the end of a sternotomy wire. A culture of yellow discharge ultimately grew Staphylococcus aureus.

SCF is a rare, and sometimes devastating, complication of cardiac surgery that occurred in 0.23% of cases at 1-year in a single center study of 12,297 patients over 9 years.1 As in this case, it may also present distantly from the time of surgery. The risk of SCF increases with smoking, previous sternal wound infection, renal failure, and use of bone wax during surgery.1

As soon as there was concern for SCF as a possible diagnosis, the patient was referred to, and quickly evaluated by, Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ultrasound and computed tomography imaging did not reveal any osteomyelitis or deep mediastinal disease. He was treated with debridement and removal of the sternotomy wire. At the 1-year follow-up, he had no further episodes of skin infection in the area.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Steingrímsson S, Gustafsson R, Gudbjartsson T, et al. Sternocutaneous fistulas after cardiac surgery: incidence and late outcome during a ten-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1910-1915. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.012

While a squamous cell carcinoma presenting this way is perhaps more common, this nonhealing draining papule over a sternal scar was actually a sternocutaneous fistula (SCF). Examination revealed multiple bound down pits along the sternotomy scar. Very gentle probing of the papule in consideration of biopsy revealed a wire foreign body—the end of a sternotomy wire. A culture of yellow discharge ultimately grew Staphylococcus aureus.

SCF is a rare, and sometimes devastating, complication of cardiac surgery that occurred in 0.23% of cases at 1-year in a single center study of 12,297 patients over 9 years.1 As in this case, it may also present distantly from the time of surgery. The risk of SCF increases with smoking, previous sternal wound infection, renal failure, and use of bone wax during surgery.1

As soon as there was concern for SCF as a possible diagnosis, the patient was referred to, and quickly evaluated by, Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ultrasound and computed tomography imaging did not reveal any osteomyelitis or deep mediastinal disease. He was treated with debridement and removal of the sternotomy wire. At the 1-year follow-up, he had no further episodes of skin infection in the area.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

While a squamous cell carcinoma presenting this way is perhaps more common, this nonhealing draining papule over a sternal scar was actually a sternocutaneous fistula (SCF). Examination revealed multiple bound down pits along the sternotomy scar. Very gentle probing of the papule in consideration of biopsy revealed a wire foreign body—the end of a sternotomy wire. A culture of yellow discharge ultimately grew Staphylococcus aureus.

SCF is a rare, and sometimes devastating, complication of cardiac surgery that occurred in 0.23% of cases at 1-year in a single center study of 12,297 patients over 9 years.1 As in this case, it may also present distantly from the time of surgery. The risk of SCF increases with smoking, previous sternal wound infection, renal failure, and use of bone wax during surgery.1

As soon as there was concern for SCF as a possible diagnosis, the patient was referred to, and quickly evaluated by, Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ultrasound and computed tomography imaging did not reveal any osteomyelitis or deep mediastinal disease. He was treated with debridement and removal of the sternotomy wire. At the 1-year follow-up, he had no further episodes of skin infection in the area.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Steingrímsson S, Gustafsson R, Gudbjartsson T, et al. Sternocutaneous fistulas after cardiac surgery: incidence and late outcome during a ten-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1910-1915. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.012

1. Steingrímsson S, Gustafsson R, Gudbjartsson T, et al. Sternocutaneous fistulas after cardiac surgery: incidence and late outcome during a ten-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1910-1915. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.012

Itchy belly

Examination revealed diffusely bordered periumbilical pink to violet scaly plaques consistent with nickel allergic contact dermatitis (Ni-ACD). The patient was wearing a belt with a buckle containing nickel, which had begun dispersing nickel. Her earlobes were also pierced and had similar scale and erythema around the metal earring studs

Ni-ACD is the most common, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction worldwide. It affects 10% of people in the United States with a strong female predominance and a 4-fold increase in the last 30 years.1 The induction of nickel delayed-type hypersensitivity has been well-studied and includes nickel corrosion dissolving into a solution and exceeding an immunogenic threshold. Piercing practices, sweat, and friction facilitate this process.

Gold jewelry that’s less than 24 karat, “white gold,” and stainless steel all contain nickel and may cause allergy in sensitized individuals. It’s wise to assume that any shiny metal fashion accessory contains nickel, unless proven otherwise. Items can be tested for the presence of nickel with an inexpensive kit containing dimethylglyoxime.

Symptoms of Ni-ACD may range from mild erythema to thickened and weepy lichenified plaques. Distribution is often present at the site of exposure but may also be seen on the eyelids or hands from nickel transfer. A systematized reaction or id reaction is uncommon but can occur. Allergic contact dermatitis can be distinguished from psoriasis by a fading border rather than a sharp, well-demarcated border.

The patient in this case switched to a nonmetallic belt and earrings with plastic studs. She was prescribed topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% bid for 3 weeks, which led to clearance of her rash.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Silverberg N, Pelletier JL, Jacob SE, et al. Nickel allergic contact dermatitis: identification, treatment, and prevention. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20200628. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0628

Examination revealed diffusely bordered periumbilical pink to violet scaly plaques consistent with nickel allergic contact dermatitis (Ni-ACD). The patient was wearing a belt with a buckle containing nickel, which had begun dispersing nickel. Her earlobes were also pierced and had similar scale and erythema around the metal earring studs

Ni-ACD is the most common, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction worldwide. It affects 10% of people in the United States with a strong female predominance and a 4-fold increase in the last 30 years.1 The induction of nickel delayed-type hypersensitivity has been well-studied and includes nickel corrosion dissolving into a solution and exceeding an immunogenic threshold. Piercing practices, sweat, and friction facilitate this process.

Gold jewelry that’s less than 24 karat, “white gold,” and stainless steel all contain nickel and may cause allergy in sensitized individuals. It’s wise to assume that any shiny metal fashion accessory contains nickel, unless proven otherwise. Items can be tested for the presence of nickel with an inexpensive kit containing dimethylglyoxime.

Symptoms of Ni-ACD may range from mild erythema to thickened and weepy lichenified plaques. Distribution is often present at the site of exposure but may also be seen on the eyelids or hands from nickel transfer. A systematized reaction or id reaction is uncommon but can occur. Allergic contact dermatitis can be distinguished from psoriasis by a fading border rather than a sharp, well-demarcated border.

The patient in this case switched to a nonmetallic belt and earrings with plastic studs. She was prescribed topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% bid for 3 weeks, which led to clearance of her rash.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Examination revealed diffusely bordered periumbilical pink to violet scaly plaques consistent with nickel allergic contact dermatitis (Ni-ACD). The patient was wearing a belt with a buckle containing nickel, which had begun dispersing nickel. Her earlobes were also pierced and had similar scale and erythema around the metal earring studs

Ni-ACD is the most common, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction worldwide. It affects 10% of people in the United States with a strong female predominance and a 4-fold increase in the last 30 years.1 The induction of nickel delayed-type hypersensitivity has been well-studied and includes nickel corrosion dissolving into a solution and exceeding an immunogenic threshold. Piercing practices, sweat, and friction facilitate this process.

Gold jewelry that’s less than 24 karat, “white gold,” and stainless steel all contain nickel and may cause allergy in sensitized individuals. It’s wise to assume that any shiny metal fashion accessory contains nickel, unless proven otherwise. Items can be tested for the presence of nickel with an inexpensive kit containing dimethylglyoxime.

Symptoms of Ni-ACD may range from mild erythema to thickened and weepy lichenified plaques. Distribution is often present at the site of exposure but may also be seen on the eyelids or hands from nickel transfer. A systematized reaction or id reaction is uncommon but can occur. Allergic contact dermatitis can be distinguished from psoriasis by a fading border rather than a sharp, well-demarcated border.

The patient in this case switched to a nonmetallic belt and earrings with plastic studs. She was prescribed topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% bid for 3 weeks, which led to clearance of her rash.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Silverberg N, Pelletier JL, Jacob SE, et al. Nickel allergic contact dermatitis: identification, treatment, and prevention. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20200628. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0628

1. Silverberg N, Pelletier JL, Jacob SE, et al. Nickel allergic contact dermatitis: identification, treatment, and prevention. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20200628. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0628

Nonhealing incision and drainage site

Additional history from the family revealed that they were cleaning the wound with copious amounts of hydrogen peroxide twice a week—a practice that impedes wound healing and was ultimately the cause of this patient’s wound closure delay.

A nonhealing wound should be carefully evaluated to rule out malignancy, infection, or an inflammatory disorder such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). In this case, punch biopsies were performed to exclude PG and malignancy, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. Additionally, punch biopsies were performed for bacterial and fungal tissue culture. A complete blood count with differential was obtained to evaluate for signs of infection or hematologic malignancy. All work-ups and biopsies were consistent with a noninfected surgical wound.

Widely available over the counter in 3% to 5% solutions, hydrogen peroxide is used as a low-cost antiseptic for minor cuts and wounds. Data are mixed as to whether hydrogen peroxide improves or impedes wound healing when used outside of initial first aid or postoperatively.1 At higher concentrations, it uniformly causes skin necrosis. Owing to its debriding effect, it is FDA approved to treat seborrheic keratoses as an alternative to cryotherapy or electrodessication and curettage.

At the time of this work-up, and in the absence of other signs of infection, the patient and family were told to stop using hydrogen peroxide. Care instructions were changed to daily topical petroleum jelly and wound occlusion. Four weeks after wound care changes were made, the wound had re-epithelialized completely and reduced in size by two-thirds.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Murphy EC, Friedman AJ. Hydrogen peroxide and cutaneous biology: translational applications, benefits, and risks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1379-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.030

Additional history from the family revealed that they were cleaning the wound with copious amounts of hydrogen peroxide twice a week—a practice that impedes wound healing and was ultimately the cause of this patient’s wound closure delay.

A nonhealing wound should be carefully evaluated to rule out malignancy, infection, or an inflammatory disorder such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). In this case, punch biopsies were performed to exclude PG and malignancy, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. Additionally, punch biopsies were performed for bacterial and fungal tissue culture. A complete blood count with differential was obtained to evaluate for signs of infection or hematologic malignancy. All work-ups and biopsies were consistent with a noninfected surgical wound.

Widely available over the counter in 3% to 5% solutions, hydrogen peroxide is used as a low-cost antiseptic for minor cuts and wounds. Data are mixed as to whether hydrogen peroxide improves or impedes wound healing when used outside of initial first aid or postoperatively.1 At higher concentrations, it uniformly causes skin necrosis. Owing to its debriding effect, it is FDA approved to treat seborrheic keratoses as an alternative to cryotherapy or electrodessication and curettage.

At the time of this work-up, and in the absence of other signs of infection, the patient and family were told to stop using hydrogen peroxide. Care instructions were changed to daily topical petroleum jelly and wound occlusion. Four weeks after wound care changes were made, the wound had re-epithelialized completely and reduced in size by two-thirds.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Additional history from the family revealed that they were cleaning the wound with copious amounts of hydrogen peroxide twice a week—a practice that impedes wound healing and was ultimately the cause of this patient’s wound closure delay.

A nonhealing wound should be carefully evaluated to rule out malignancy, infection, or an inflammatory disorder such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). In this case, punch biopsies were performed to exclude PG and malignancy, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. Additionally, punch biopsies were performed for bacterial and fungal tissue culture. A complete blood count with differential was obtained to evaluate for signs of infection or hematologic malignancy. All work-ups and biopsies were consistent with a noninfected surgical wound.

Widely available over the counter in 3% to 5% solutions, hydrogen peroxide is used as a low-cost antiseptic for minor cuts and wounds. Data are mixed as to whether hydrogen peroxide improves or impedes wound healing when used outside of initial first aid or postoperatively.1 At higher concentrations, it uniformly causes skin necrosis. Owing to its debriding effect, it is FDA approved to treat seborrheic keratoses as an alternative to cryotherapy or electrodessication and curettage.

At the time of this work-up, and in the absence of other signs of infection, the patient and family were told to stop using hydrogen peroxide. Care instructions were changed to daily topical petroleum jelly and wound occlusion. Four weeks after wound care changes were made, the wound had re-epithelialized completely and reduced in size by two-thirds.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Murphy EC, Friedman AJ. Hydrogen peroxide and cutaneous biology: translational applications, benefits, and risks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1379-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.030

1. Murphy EC, Friedman AJ. Hydrogen peroxide and cutaneous biology: translational applications, benefits, and risks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1379-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.030

Hyperpigmented lesion on left palm

A 17-year-old high school baseball player presented to a sports medicine clinic for left anterior knee pain. During the exam, a hyperpigmented lesion was incidentally noted on his left palm. The patient, who also played basketball and football, was unsure of how long he’d had the lesion, and he did not recall having any prior lesions on his hand. He denied any discomfort or significant past medical history. There was no known family history of skin cancers, but the patient did report that his brother, also an athlete, had a similar lesion on his hand.

On closer examination, scattered black dots were noted within a 2 × 1–cm thickened keratotic plaque at the hypothenar eminence of the patient’s left hand (Figure). There was no tenderness, erythema, warmth, or disruption of normal skin architecture or drainage.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Posttraumatic tache noir

Posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet) is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically.

Our patient was a competitive baseball player, and he noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to the author’s clinical experience with similar cases.

Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.1 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.1-3 Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse. One should have a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis in patients who participate in any sport that might lead to shearing forces involving the volar aspect of the hands or feet.

Confirmation is obtained through a simple procedure. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.4

Other lesions may havea similar appearance

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris similarly contains puncta but typically appears as a raised lesion with a disruption of the stratum corneum.5

Acral melanoma can be distinguished from tache/talon noir by dermoscopic evaluation and/or paring of the corneum. On dermoscopic evaluation, both acral melanoma and tache/talon noir will reveal parallel ridge patterns; this finding has an 86% sensitivity and 96% specificity for early acral melanoma.6 What differentiates the 2 is the “satellite globules” or “pebbles on a ridge” that are seen with a subcorneal hematoma. Furthermore, paring the corneum would demonstrate an absence of blood within the ridges of the skin shavings, pointing away from tache/talon noir as the diagnosis.1-3,5-7

Traumatic tattoo can also mimic tache/talon noir, due to foreign-material deposits in the skin (gunpowder, carbon, lead, dirt, and asphalt). A history of penetrating trauma should help to narrow the differential. Attempts at paring with traumatic tattoo may or may not help with differentiation.1

In this case, time does heal all wounds

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade, which can partially or completely remove the pigmentation from within the parallel ridges.3,5,8

Our patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

1. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

2. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

3. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

4. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

5. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.079

6. Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01174.x

7. Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory condition, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:31-43.

8. Kaminska-Winciorek G, Spiewak R. Tips and tricks in the dermoscopy of pigmented lesions. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-14

A 17-year-old high school baseball player presented to a sports medicine clinic for left anterior knee pain. During the exam, a hyperpigmented lesion was incidentally noted on his left palm. The patient, who also played basketball and football, was unsure of how long he’d had the lesion, and he did not recall having any prior lesions on his hand. He denied any discomfort or significant past medical history. There was no known family history of skin cancers, but the patient did report that his brother, also an athlete, had a similar lesion on his hand.

On closer examination, scattered black dots were noted within a 2 × 1–cm thickened keratotic plaque at the hypothenar eminence of the patient’s left hand (Figure). There was no tenderness, erythema, warmth, or disruption of normal skin architecture or drainage.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Posttraumatic tache noir

Posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet) is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically.

Our patient was a competitive baseball player, and he noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to the author’s clinical experience with similar cases.

Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.1 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.1-3 Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse. One should have a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis in patients who participate in any sport that might lead to shearing forces involving the volar aspect of the hands or feet.

Confirmation is obtained through a simple procedure. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.4

Other lesions may havea similar appearance

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris similarly contains puncta but typically appears as a raised lesion with a disruption of the stratum corneum.5

Acral melanoma can be distinguished from tache/talon noir by dermoscopic evaluation and/or paring of the corneum. On dermoscopic evaluation, both acral melanoma and tache/talon noir will reveal parallel ridge patterns; this finding has an 86% sensitivity and 96% specificity for early acral melanoma.6 What differentiates the 2 is the “satellite globules” or “pebbles on a ridge” that are seen with a subcorneal hematoma. Furthermore, paring the corneum would demonstrate an absence of blood within the ridges of the skin shavings, pointing away from tache/talon noir as the diagnosis.1-3,5-7

Traumatic tattoo can also mimic tache/talon noir, due to foreign-material deposits in the skin (gunpowder, carbon, lead, dirt, and asphalt). A history of penetrating trauma should help to narrow the differential. Attempts at paring with traumatic tattoo may or may not help with differentiation.1

In this case, time does heal all wounds

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade, which can partially or completely remove the pigmentation from within the parallel ridges.3,5,8

Our patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

A 17-year-old high school baseball player presented to a sports medicine clinic for left anterior knee pain. During the exam, a hyperpigmented lesion was incidentally noted on his left palm. The patient, who also played basketball and football, was unsure of how long he’d had the lesion, and he did not recall having any prior lesions on his hand. He denied any discomfort or significant past medical history. There was no known family history of skin cancers, but the patient did report that his brother, also an athlete, had a similar lesion on his hand.

On closer examination, scattered black dots were noted within a 2 × 1–cm thickened keratotic plaque at the hypothenar eminence of the patient’s left hand (Figure). There was no tenderness, erythema, warmth, or disruption of normal skin architecture or drainage.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Posttraumatic tache noir

Posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet) is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically.

Our patient was a competitive baseball player, and he noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to the author’s clinical experience with similar cases.

Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.1 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.1-3 Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse. One should have a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis in patients who participate in any sport that might lead to shearing forces involving the volar aspect of the hands or feet.

Confirmation is obtained through a simple procedure. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.4

Other lesions may havea similar appearance

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris similarly contains puncta but typically appears as a raised lesion with a disruption of the stratum corneum.5

Acral melanoma can be distinguished from tache/talon noir by dermoscopic evaluation and/or paring of the corneum. On dermoscopic evaluation, both acral melanoma and tache/talon noir will reveal parallel ridge patterns; this finding has an 86% sensitivity and 96% specificity for early acral melanoma.6 What differentiates the 2 is the “satellite globules” or “pebbles on a ridge” that are seen with a subcorneal hematoma. Furthermore, paring the corneum would demonstrate an absence of blood within the ridges of the skin shavings, pointing away from tache/talon noir as the diagnosis.1-3,5-7

Traumatic tattoo can also mimic tache/talon noir, due to foreign-material deposits in the skin (gunpowder, carbon, lead, dirt, and asphalt). A history of penetrating trauma should help to narrow the differential. Attempts at paring with traumatic tattoo may or may not help with differentiation.1

In this case, time does heal all wounds

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade, which can partially or completely remove the pigmentation from within the parallel ridges.3,5,8

Our patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

1. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

2. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

3. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

4. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

5. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.079

6. Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01174.x

7. Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory condition, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:31-43.

8. Kaminska-Winciorek G, Spiewak R. Tips and tricks in the dermoscopy of pigmented lesions. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-14

1. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

2. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

3. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

4. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

5. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.079

6. Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01174.x

7. Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory condition, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:31-43.

8. Kaminska-Winciorek G, Spiewak R. Tips and tricks in the dermoscopy of pigmented lesions. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-14

Enlarging purple plaque on leg

Clinical and dermoscopic features were consistent with a sporadic angiokeratoma, a benign ectasia of vessels associated with keratinization. Diagnosis was confirmed with shave biopsy.

Sporadic angiokeratomas are common and increase with age. They may occur anywhere on the skin, including mucous membranes. Dermoscopy of an angiokeratoma will reveal vascular lacunae—small pools of red or near black blood—as well as keratin scale, which appears as a white veil or shiny white lines.1

Other subtypes of angiokeratomas may be more widespread, including angiokeratoma of Fordyce, which manifests on the vulva and scrotum (usually in adulthood), or angiokeratoma circumscriptum, which occurs congenitally. There are some rare syndromic conditions associated with widespread angiokeratomas, such as Fabry disease.

The differential diagnosis for this solitary, vascular-appearing papule or plaque includes cherry angioma, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma. Over time, the keratinization may increase, and lesions may look like a wart. A punch or shave biopsy will distinguish an angiokeratoma from other types of lesions. When a lesion is small enough, it may also be curative.

Angiokeratomas do not require treatment. However, because they may occur in cosmetically sensitive areas or bleed when traumatized, remedies are often sought. Excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, and vascular laser are all possible treatments.

In this case, the patient was treated with curettage and light electrocautery, which left a small scar.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

Clinical and dermoscopic features were consistent with a sporadic angiokeratoma, a benign ectasia of vessels associated with keratinization. Diagnosis was confirmed with shave biopsy.

Sporadic angiokeratomas are common and increase with age. They may occur anywhere on the skin, including mucous membranes. Dermoscopy of an angiokeratoma will reveal vascular lacunae—small pools of red or near black blood—as well as keratin scale, which appears as a white veil or shiny white lines.1

Other subtypes of angiokeratomas may be more widespread, including angiokeratoma of Fordyce, which manifests on the vulva and scrotum (usually in adulthood), or angiokeratoma circumscriptum, which occurs congenitally. There are some rare syndromic conditions associated with widespread angiokeratomas, such as Fabry disease.

The differential diagnosis for this solitary, vascular-appearing papule or plaque includes cherry angioma, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma. Over time, the keratinization may increase, and lesions may look like a wart. A punch or shave biopsy will distinguish an angiokeratoma from other types of lesions. When a lesion is small enough, it may also be curative.

Angiokeratomas do not require treatment. However, because they may occur in cosmetically sensitive areas or bleed when traumatized, remedies are often sought. Excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, and vascular laser are all possible treatments.

In this case, the patient was treated with curettage and light electrocautery, which left a small scar.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Clinical and dermoscopic features were consistent with a sporadic angiokeratoma, a benign ectasia of vessels associated with keratinization. Diagnosis was confirmed with shave biopsy.

Sporadic angiokeratomas are common and increase with age. They may occur anywhere on the skin, including mucous membranes. Dermoscopy of an angiokeratoma will reveal vascular lacunae—small pools of red or near black blood—as well as keratin scale, which appears as a white veil or shiny white lines.1

Other subtypes of angiokeratomas may be more widespread, including angiokeratoma of Fordyce, which manifests on the vulva and scrotum (usually in adulthood), or angiokeratoma circumscriptum, which occurs congenitally. There are some rare syndromic conditions associated with widespread angiokeratomas, such as Fabry disease.

The differential diagnosis for this solitary, vascular-appearing papule or plaque includes cherry angioma, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma. Over time, the keratinization may increase, and lesions may look like a wart. A punch or shave biopsy will distinguish an angiokeratoma from other types of lesions. When a lesion is small enough, it may also be curative.

Angiokeratomas do not require treatment. However, because they may occur in cosmetically sensitive areas or bleed when traumatized, remedies are often sought. Excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, and vascular laser are all possible treatments.

In this case, the patient was treated with curettage and light electrocautery, which left a small scar.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

1. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

Rash in an immunocompromised patient

The patient’s history and presentation, as well as a positive varicella zoster virus (VZV) culture of vesicular fluid, led to a diagnosis of disseminated herpes zoster (DHZ). The patient’s laboratory studies were remarkable for mild lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver function tests. Shave and punch biopsies of the lesion showed ballooning epithelial necrosis with multinucleated giant cells.

DHZ is characterized by more than 20 vesicles outside of a primary or adjacent dermatome and is caused by extensive reactivation of VZV. DHZ is most often encountered in immunocompromised patients.1 Untreated DHZ can lead to encephalitis, myelitis, nerve palsies, pneumonitis, hepatitis, and ocular complications.

Diagnosis is usually made clinically and confirmed by a polymerase chain reaction test, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or viral culture.2 In immunocompetent patients, uncomplicated DHZ is treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times daily, valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily, or famciclovir 500 mg 3 times daily for 7 days. Hospital admission for intravenous acyclovir is recommended for immunocompromised patients, especially those with internal organ involvement, such as hepatitis or encephalitis.3

Early treatment is imperative to avoid life-threatening complications. Active herpes zoster lesions are infectious by contact with vesicular fluid until they dry and crust over. Patients should be instructed to avoid contact with susceptible people, including those who are immunocompromised, babies who have not received their varicella vaccine, and pregnant women. It is important to keep DHZ on the differential—especially in an immunosuppressed patient with a diffuse vesicular rash—as it can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

Our patient was treated with oral valacyclovir 1 g tid for 10 days and he improved without developing systemic symptoms.

Image courtesy of Christen B. Samaan, MD. Text courtesy of Christen B. Samaan, MD, and Matthew F. Helm, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Nanjiba Nawaz, BA, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey.

1. Bollea-Garlatti ML, Bollea-Garlatti LA, Vacas AS, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in a population with disseminated herpes zoster: a retrospective cohort study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:145-152. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2016.10.009

2. Chiriac A, Chiriac AE, Podoleanu C, et al. Disseminated cutaneous herpes zoster—a frequently misdiagnosed entity. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1089-1091. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13370

3. Lewis DJ, Schlichte MJ, Dao H Jr. Atypical disseminated herpes zoster: management guidelines in immunocompromised patients. Cutis. 2017;100:321;324;330.

The patient’s history and presentation, as well as a positive varicella zoster virus (VZV) culture of vesicular fluid, led to a diagnosis of disseminated herpes zoster (DHZ). The patient’s laboratory studies were remarkable for mild lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver function tests. Shave and punch biopsies of the lesion showed ballooning epithelial necrosis with multinucleated giant cells.

DHZ is characterized by more than 20 vesicles outside of a primary or adjacent dermatome and is caused by extensive reactivation of VZV. DHZ is most often encountered in immunocompromised patients.1 Untreated DHZ can lead to encephalitis, myelitis, nerve palsies, pneumonitis, hepatitis, and ocular complications.

Diagnosis is usually made clinically and confirmed by a polymerase chain reaction test, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or viral culture.2 In immunocompetent patients, uncomplicated DHZ is treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times daily, valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily, or famciclovir 500 mg 3 times daily for 7 days. Hospital admission for intravenous acyclovir is recommended for immunocompromised patients, especially those with internal organ involvement, such as hepatitis or encephalitis.3

Early treatment is imperative to avoid life-threatening complications. Active herpes zoster lesions are infectious by contact with vesicular fluid until they dry and crust over. Patients should be instructed to avoid contact with susceptible people, including those who are immunocompromised, babies who have not received their varicella vaccine, and pregnant women. It is important to keep DHZ on the differential—especially in an immunosuppressed patient with a diffuse vesicular rash—as it can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

Our patient was treated with oral valacyclovir 1 g tid for 10 days and he improved without developing systemic symptoms.

Image courtesy of Christen B. Samaan, MD. Text courtesy of Christen B. Samaan, MD, and Matthew F. Helm, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Nanjiba Nawaz, BA, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey.