User login

New myeloma drugs improve response and extend survival

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, and Dr Ken Anderson, the Kraft Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an international thought leader and investigator in myeloma, discuss three cases of patients with myeloma that are indicative of the remarkable therapeutic advances in oncology in general, and in myeloma in particular.

Listen to the podcast below

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, and Dr Ken Anderson, the Kraft Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an international thought leader and investigator in myeloma, discuss three cases of patients with myeloma that are indicative of the remarkable therapeutic advances in oncology in general, and in myeloma in particular.

Listen to the podcast below

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, and Dr Ken Anderson, the Kraft Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an international thought leader and investigator in myeloma, discuss three cases of patients with myeloma that are indicative of the remarkable therapeutic advances in oncology in general, and in myeloma in particular.

Listen to the podcast below

New myeloma drugs improve response and extend survival

DR HENRY I thought we might discuss some cases of patients with myeloma, starting with a relatively simple case and ending with one that is a little more complicated. For the first case, we have a 56-year-old healthy man with IgG kappa myeloma whose work-up shows he has multiple lytic bone lesions. He has normal renal function, normal calcium, and he’s transplant-eligible by other health issues. I’ll leave the cytogenetics up to you if that changes your approach. How would you develop or pose some options for this man’s treatment to begin with?

DR ANDERSON It’s important to start out by saying that we, in myeloma, have many new classes of drugs and many new opportunities to choose from to treat this patient.1 As you know, we have proteasome inhibitors, the first-generation bortezomib, then carfilzomib and ixazomib. We have the immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), thalidomide, and now lenalidomide and pomalidomide. We have a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved called panobinostat, and we have 2 monoclonal antibodies approved, elotuzumab and daratumumab. These classes of medicine have made it possible for 20 different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in the last 10-15 years. These agents, having been tested in advanced myeloma, have moved toward initial management.

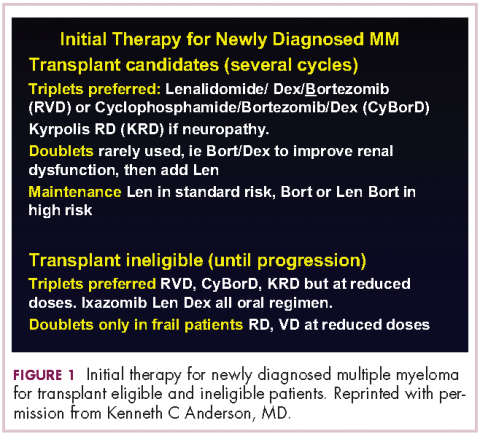

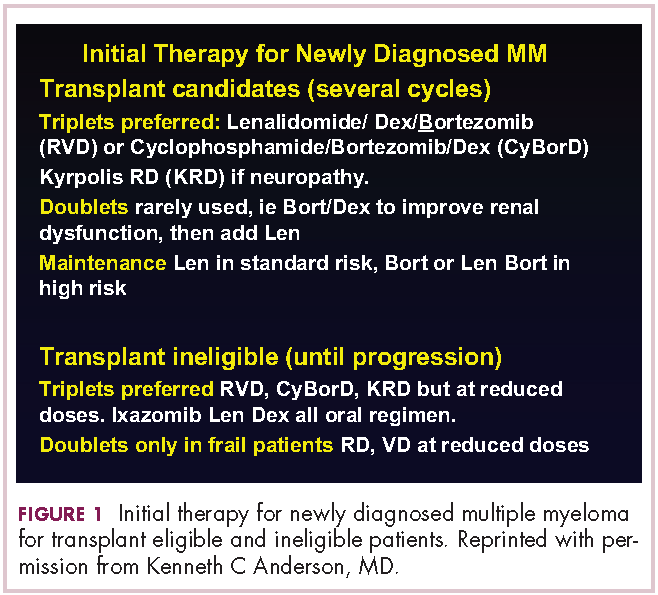

This person is 50 years old. He has adequate liver, heart, lung, and kidney function, so he would be eligible for high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. In terms of initial management, there are many options (Figure 1). We strongly recommend that triplet therapy be used initially. The most common triplets would be lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD)2,3 or cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD).4 If this man had neuropathy, perhaps carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, with lenalidomide and dexamethasone could have been used. Why do we use these? The extent and frequency of response with these triplets is nearly universal overall response rate, with three-quarters very good partial and half-complete responses, including minimal residual disease negative responses. In this patient, we would therefore recommend treatment with either RVD or CyBorD for several cycles to maximal response.

He would then have autologous stem cells collected, and it is still the standard of care to proceed to high-dose melphalan and a single high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. The cytogenetics are important: if this patient has standard-risk multiple myeloma, then lenalidomide maintenance would be given after transplant. It is now FDA-approved for this purpose because it can prolong both progression-free and – most importantly – overall survival.5 Standard-risk cytogenetics might, for example, include hyperdiploidy or translocation 11;14. On the other hand, if his myeloma were high-risk and characterized, for example, by 17p deletion, we would carry out the same induction and transplantation, but we would alter the maintenance to incorporate a proteasome inhibitor. Lenalidomide and bortezomib, for example, could be combined. Early data show that using combined maintenance therapy with lenalidomide and bortezomib, can overcome the early relapses that are characteristic of high-risk disease.6

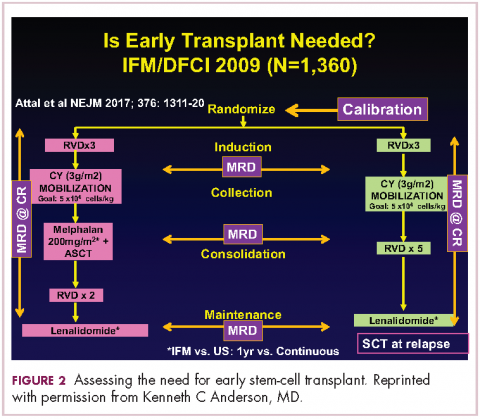

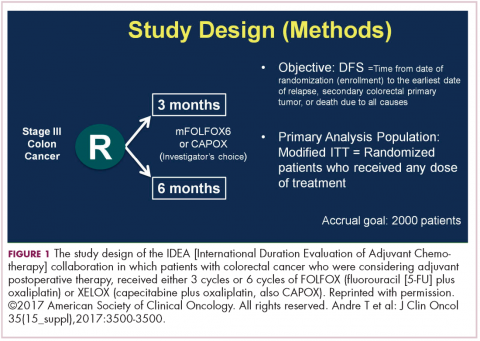

Because of the extent and frequency of response to combination novel therapies, we have undertaken with our French colleagues a clinical trial of RVD in newly diagnosed patients – such as this patient – followed by stem-cell collection in all patients (Figure 2). Then there is a randomization to either early high-dose therapy, melphalan, and autologous stem-cell transplantation, followed by lenalidomide maintenance; or in the other cohort, harvesting of stem cells, additional RVD, and then maintenance with lenalidomide, saving the stem-cell transplant for later.

The French portion of this trial was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier in 2017.7 It showed that patients who received RVD, high-dose melphalan, stem-cell transplant, and had 1 year of lenalidomide maintenance, had a progression-free survival advantage of about 1 year, without an overall survival advantage; compared with those patients who received RVD and lenalidomide maintenance, saving the transplant for later. I would hasten to add that lenalidomide maintenance was given for only 1 year in this trial, and patients in the RVD-only or RVD-and-transplant arms of this trial relapsed after the lenalidomide maintenance was discontinued.

The American portion of this trial is identical. That is, RVD induction is being given and all patients have a stem-cell collection. Half of the patients then go to high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant early, and half of them have the transplant only later at the time of relapse. A major difference, however, is that in both the RVD-only and RVD-and-transplant cohorts, patients receive lenalidomide maintenance until progression. This trial has been ongoing since 2009 and is still ongoing, which tells us that patients in both arms – the RVD-only as well as the RVD-and-transplant arms – are doing well.

In the recent STAMINA trial, all patients underwent a single high-dose therapy and transplant. Then there was a randomization to lenalidomide maintenance only in 1 cohort; a randomization to consolidation with RVD posttransplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the second cohort; or a randomization to a second high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the third cohort.8 I mention this because the outcomes in all 3 cohorts was similar.

I believe this tells us strongly that high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation twice – so-called tandem transplant – is no longer a major option in multiple myeloma. For now, however, in this patient, the standard of care would be to undergo induction therapy with triplet, novel combination treatment. Then, stem cells would be collected and high-dose therapy stem-cell transplant would be done, followed either by lenalidomide maintenance for standard disease or lenalidomide and bortezomib maintenance for high-risk disease. We won’t really know if we can delay transplant until the trials I’ve mentioned totally read out. In my clinical practice, if patients have had a major response to their induction therapy and have stem cells harvested, we can then offer them the opportunity to use maintenance therapy and save the transplant as a potential option for later, when myeloma relapses.

DR HENRY In summary then, this would be, in 2017, off-protocol while the data is pending: it’s reasonable to get a deep induction response, collect stem cells, have a discussion with the patient, and then consider high-dose therapy or not.

DR ANDERSON Yes. I think it’s reasonable to discuss it. We need to be open and honest with patients that the standard of care remains transplant, that you incorporate novel treatments before the transplant and novel treatments as maintenance after the transplant. The happy news is that the outcome, especially for patients who have standard-risk myeloma, is at least a decade or longer progression-free survival. It’s an optimistic picture. The data in terms of transplant being needed or not, will come within the next several years.

For now, it is a standard of care to use 1 high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant in this setting. I will add into our discussion with patients – besides the opportunity to harvest stem cells and think about whether one needs to do a transplant early on or not – is the issue of toxicity. High-dose melphalan by itself has a small but real secondary incidence of cancer, myelodysplasia, or leukemia. If one uses lenalidomide maintenance after melphalan transplantation treatment, that risk of secondary cancer is slightly increased.

In my experience, if patients have achieved a complete response with induction therapy only, it’s not unreasonable to offer early transplant and be clear that’s the standard of care. The alternative is maintenance with lenalidomide, knowing once the stem cells have been harvested, that transplantation can be an option to treat relapsed myeloma. We have many other options available as well. Time will tell in terms of the ongoing randomized trials as to whether transplant remains central to our treatment paradigm.

DR HENRY This leads us to our second patient. Here we have an older man of 74 years. He’s a professional piano player, so we want to try to avoid peripheral neuropathy in him. He has some mild renal insufficiency and some coronary artery disease, so he’s deemed transplant-ineligible. He has IgG kappa myeloma, and he’s brand new. What would you consider to be options for him for treatment?

DR ANDERSON This brings up the issue of a transplant-ineligible patient. He has significant comorbidity that would make transplantation an increased risk. What we would recommend in such a patient is still triplet induction therapy incorporating novel agents (Figure 1). Lenalidomide, the immunomodulatory drug, can safely be given in the context of neuropathy because it does not cause significant neuropathy. It would need to be dose modified, depending on the degree of renal insufficiency. We would recommend also including proteasome inhibitors. Bortezomib, the first-generation proteasome inhibitor, would be contraindicated because it does have a small but real attendant neuropathy. If, however, it is given weekly and subcutaneously, the risk of attendant neuropathy is quite low. In this patient, therefore, one could start with lenalidomide and bortezomib weekly and subcutaneously,1,2 with a very early and vigilant follow-up for the earliest signs of neuropathy, so as not to allow it to develop and compromise his career.

Alternatively, one could use a proteasome inhibitor that does not have attendant neuropathy. Carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, does not have neuropathy.9 But we would need to have caution here, because this patient has a history of coronary artery disease, and carfilzomib has a very small, but real, incidence of cardiac toxicity so would need to be used judiciously in this setting. The third proteasome inhibitor, ixazomib, is the next-generation bortezomib-class proteasome inhibitor, and it’s oral.10 It has less neuropathy than does bortezomib, so in my view is a very realistic option for him together with lenalidomide. It does have a small incidence of neuropathy, so close monitoring for neuropathy would be indicated. We could use lenalidomide–dexamethasone as a doublet and avoid neuropathy,11 but usually doublets are reserved only for frail patients.

My recommendation, therefore, would be RVD with the bortezomib weekly or subcutaneously, or alternatively, lenalidomide, ixazomib, dexamethasone as an all-oral regimen as induction therapy. In my view, this 74-year-old patient with comorbidity is not a transplant candidate. However, one can be very optimistic with this patient. The likelihood that he could have myeloma as a chronic illness and die from something else is quite high. Initial induction triplet therapy would achieve a very high response extent and frequency. The durability would be long, especially with lenalidomide maintenance if it’s standard-risk myeloma or lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, probably ixazomib in this setting, if he were to have high-risk myeloma.

If myeloma relapses, then there are many options that could be used in this patient and achieve years of progression-free and overall survival. Indeed, he is 74 years old and will respond very well to induction triplet therapy, with many years’ duration of response due to continuous lenalidomide or lenalidomide and proteasome inhibitor maintenance. Then there are many effective options to treat relapsed therapy using triplet novel agents. Therefore, his lifespan is unlikely to be shortened by multiple myeloma.

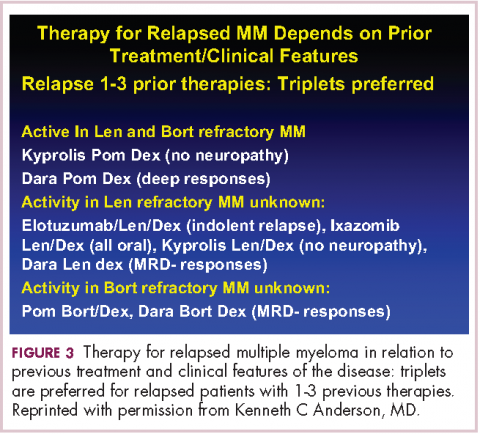

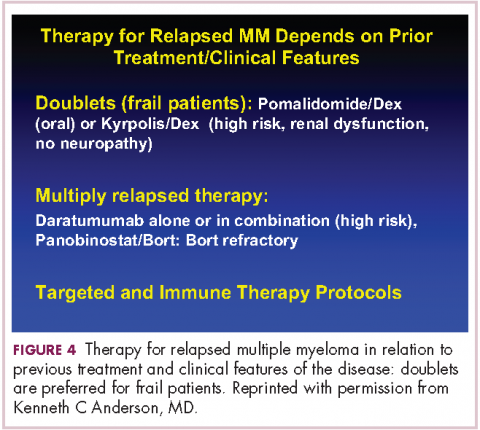

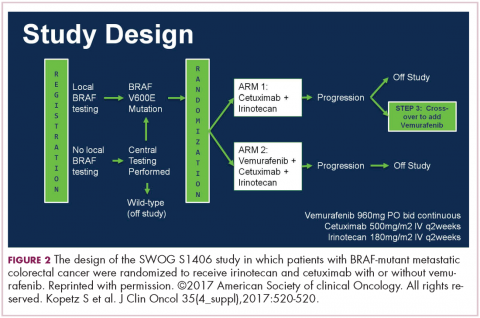

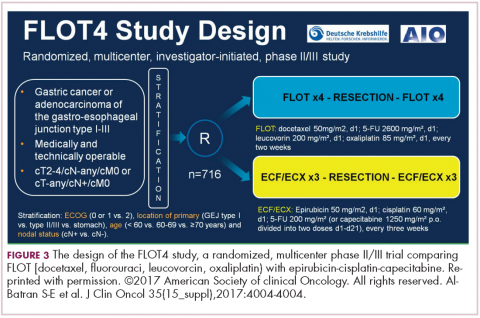

DR HENRY It’s so incredible compared with what it was when I trained. The next patient, a 45-year-old woman with IgG lambda myeloma, has had RVD induction and responded. She had lenalidomide maintenance, but then she progressed, and she got her stem-cell transplant, and she’s progressing after that. I guess we’re looking here to fold in some of the newer agents. How you would you do that in this patient?DR ANDERSON Yes. I think one of the most remarkable and exciting developments with myeloma is the rapid approval of the novel classes of agents that I mentioned earlier – the proteasome inhibitors, the immunomodulatory drugs, the HDAC inhibitor, and the monoclonal antibodies.1 They’re particularly relevant in a patient such as this one, whose myeloma has relapsed after what would be considered standard therapy for a young person with standard-risk myeloma. This patient had RVD and maintenance therapy, and then progressed. The transplant was given for relapsed myeloma. The opportunity to use stem-cell transplant in patients when myeloma becomes active after maintenance should not be forgotten as it can be very effective. In all the trials done to date in which early versus late transplant are compared, there have been similar outcomes. Therefore, if the transplant isn’t done early, don’t forget that it’s an option at the time the myeloma progresses. I do want to mention, that there are lots of options for relapsed myeloma (Figures 3 and 4). I mentioned RVD or CyBorD as initial triplet therapies.2-4 In North America, those are the 2 most common regimens. If myeloma then relapses and is resistant to RVD or to CyBorD, then we need to identify alternatives.

We also need to think about the comorbidities in the patient – issues such as age, neuropathy, presence of renal dysfunction, and other clinical factors. And we need to think about what treatment they’ve had in the past. This patient has had RVD, maintenance with lenalidomide, and a stem-cell transplant. We can offer patients a variety of therapies, but in the context of resistance to the first-generation proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and the first-generation immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide, we would strongly recommend the second-generation immunomodulatory drug pomalidomide12 together with a second-generation proteasome inhibitor, be that carfilzomib13 or ixazomib.14 When one uses the second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors together, there’s a very high frequency of response in the order of 70%-80%, which lasts years.

Besides carfilzomib and ixazomib proteasome inhibitors, we also have elotuzumab and daratumumab, the monoclonal antibodies.15-17 These agents have been FDA approved to treat patients such as this one who has had 1-3 previous therapies for their myeloma. All of them have been approved in randomized phase 3 trials compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone in the control arm.13-15,17 They’ve all been found to be superior. Although lenalidomide-dexamethasone combined with daratumumab, ixazomib, elotuzumab, or carfilzomib is superior to lenalidomide in relapsed myeloma, the situation in North America, as in this patient, is usually that patients have had lenalidomide-dexamethasone as part of their initial treatment and their myeloma is refractory to lenalidomide.

Hence, we recommend, that we go to the second-generation pomalidomide and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Having said that, the treatment paradigm is evolving. For example, the monoclonal antibody daratumumab was initially approved by the FDA in multiply relapsed disease as a single agent because it achieves a 30% response rate.16 It now has been moved earlier into the first relapse of multiple myeloma, where it achieves much higher response rates when combined with lenalidomide–dexamethasone or combined with bortezomib–dexamethasone.17,18 Response rates of 70%-80% can be achieved, including minimal residual disease negative complete responses.

Today, in a patient who has had RVD transplant and myeloma has returned, we would recommend second-generation IMiDs, pomalidomide, and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Data for daratumumab combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or with bortezomib-dexamethasone, look very promising. We need, however, to see more experience of daratumumab together with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or daratumumab together with bortezomib-dexamethasone in patients whose myeloma is refractory to RVD, that is, patients whose myeloma has returned after RVD induction treatment. Of note, pomalidomide, dexamethasone, and daratumumab have just been approved by the FDA and may also be active even in myeloma recurring after RVD treatment.19

Daratumumab in combination will be moving earlier and earlier and may be appropriate to treat the first relapse. I do want to stress, however, that at present I save daratumumab for the second or greater relapse. Daratumumab is active even when relapse occurs after treatment with second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors.

DR HENRY Before we close, I have a couple practical questions with these antibodies. Daratumumab has the track record of first-treatment severe reactions and long infusion times. How long are you anticipating the first daratumumab treatment takes? There has been some talk that maybe splitting it in half and going over 2 days is easier on the patient and the infusion center. Have you done that?

DR ANDERSON Yes, I think that’s a very important point. We need to be thinking – first and foremost – about efficacy of our therapy. Equally important, however, are the safety profile and the user-friendliness for the patient. Daratumumab infusions are quite long – on the order of 8 hours or longer on day 1 of infusion. And to date, all the clinical trials have used daratumumab infusions weekly for 8 treatments, followed by 8 treatments given every 2 weeks. Then monthly daratumumab is given as a maintenance therapy. Thus, there is a requirement for multiple outpatient clinic visits that can be prolonged.

One of the opportunities that’s being tested is to give daratumumab subcutaneously. While this is being evaluated in protocols now, the results that have been reported at our national meetings look to be quite promising in terms of efficacy, similar to results with the intravenous administration. Obviously, this would allow for a much more convenient clinic visit and shorter time for the patients being treated.

I should mention that the other antibody, elotuzumab, has been approved in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.15 The infusions with lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and the antibody elotuzumab are much shorter, on the order of 2- or 3-hour visits. The place for elotuzumab in the management of relapsed myeloma is yet to be totally defined. We tend to use it now in the setting of more indolent relapses, where patients might have a slowly rising monoclonal protein. Elotuzumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone has maintained an overall survival advantage at 4 years compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone when used in relapsed myeloma.

We are quite excited about both antibodies. Daratumumab tends to get most of the activity, as it achieves responses as a single agent,16 and the depth of the responses are markedly increased when it’s combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or bortezomib-dexamethasone.17,18 However, one shouldn’t forget elotuzumab15 based on its tolerability and the survival advantage I mentioned at 4 years.

The final point is that we think about myeloma genetically at the time of diagnosis and relapse in terms of standard or high-risk disease. One of the hallmarks of high-risk disease has been 17P deletion or P53 dysfunction. One of the most exciting outcomes of the development of monoclonal antibodies has been the responses observed even in the context of P53 deletion. Clearly, antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity, complement-mediated cytotoxicity, and other mechanisms of action of these antibodies do not require normal P53 function. The important point, therefore, is that what has previously been thought of as high-risk disease can nowadays be effectively treated with these new immune treatments, correlating with the marked improvement in survival and overall outcome.

DR HENRY We have outlined 3 kinds of myeloma patients we see, and especially interesting is the last patient, who has relapsed and then progressed, and in whom newer drugs have a role. Thank you for such a complete and thorough discussion, Dr Anderson.

1. Kumar SK, Callander NS, Alsina M, et al. Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:230-269.

2. Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:679-686.

3. Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777: a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):519-527.

4. Moreau P, Hulin C, Macro M, et al. VTD is superior to VCD prior to intensive therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the prospective IFM2013-04 trial. Blood. 2016;127:2569-2574.

5. McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. A phase III study of lenalidomide after transplant for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770-1781.

6. Nooka AK, Kaufman JL, Muppidi S, et al. Consolidation and maintenance therapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) in high risk myeloma patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:690-693.

7. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone with transplantation in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311-1320.

8. Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Comparison of autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT), bortezomib, lenalidomide (len) and dexamethasone (RVD) consolidation with len maintenance (ACM), tandem autohct with len maintenance (TAM) and autohct with len maintenance (AM) for up-front treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM): primary results from the randomized phase III trial of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN 0702 – StaMINA Trial). Abstract LBA-1. Presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, December 6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

9. Dytfeld D, Jasielec J, Griffith KA, et al: Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2014;99:e162-164.

10. Kumar SK, Berdeja JG, Niesvizky R, et al. Safety and tolerability of ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: an open-label phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1503-1512

11. Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. for the FIRST Trial Team. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917.

12. Richardson P, Siegel D, Vij R, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 2 study. Blood. 2014;123:1826-1832.

13. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. for the ASPIRE Investigators. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:142-152

14. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. for the TOURMALINE-MM1 Study Group. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;28;374:1621-1634.

15. Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. for the ELOQUENT-2 Investigators. Elotuzumab therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:621-631.

16. Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD 38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1207-1219.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1319-1331.

18. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. for the CASTOR Investigators. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:754-766.

19. Chari A, Suvannasankha A, Fay JW, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130(8):974-981.

DR HENRY I thought we might discuss some cases of patients with myeloma, starting with a relatively simple case and ending with one that is a little more complicated. For the first case, we have a 56-year-old healthy man with IgG kappa myeloma whose work-up shows he has multiple lytic bone lesions. He has normal renal function, normal calcium, and he’s transplant-eligible by other health issues. I’ll leave the cytogenetics up to you if that changes your approach. How would you develop or pose some options for this man’s treatment to begin with?

DR ANDERSON It’s important to start out by saying that we, in myeloma, have many new classes of drugs and many new opportunities to choose from to treat this patient.1 As you know, we have proteasome inhibitors, the first-generation bortezomib, then carfilzomib and ixazomib. We have the immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), thalidomide, and now lenalidomide and pomalidomide. We have a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved called panobinostat, and we have 2 monoclonal antibodies approved, elotuzumab and daratumumab. These classes of medicine have made it possible for 20 different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in the last 10-15 years. These agents, having been tested in advanced myeloma, have moved toward initial management.

This person is 50 years old. He has adequate liver, heart, lung, and kidney function, so he would be eligible for high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. In terms of initial management, there are many options (Figure 1). We strongly recommend that triplet therapy be used initially. The most common triplets would be lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD)2,3 or cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD).4 If this man had neuropathy, perhaps carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, with lenalidomide and dexamethasone could have been used. Why do we use these? The extent and frequency of response with these triplets is nearly universal overall response rate, with three-quarters very good partial and half-complete responses, including minimal residual disease negative responses. In this patient, we would therefore recommend treatment with either RVD or CyBorD for several cycles to maximal response.

He would then have autologous stem cells collected, and it is still the standard of care to proceed to high-dose melphalan and a single high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. The cytogenetics are important: if this patient has standard-risk multiple myeloma, then lenalidomide maintenance would be given after transplant. It is now FDA-approved for this purpose because it can prolong both progression-free and – most importantly – overall survival.5 Standard-risk cytogenetics might, for example, include hyperdiploidy or translocation 11;14. On the other hand, if his myeloma were high-risk and characterized, for example, by 17p deletion, we would carry out the same induction and transplantation, but we would alter the maintenance to incorporate a proteasome inhibitor. Lenalidomide and bortezomib, for example, could be combined. Early data show that using combined maintenance therapy with lenalidomide and bortezomib, can overcome the early relapses that are characteristic of high-risk disease.6

Because of the extent and frequency of response to combination novel therapies, we have undertaken with our French colleagues a clinical trial of RVD in newly diagnosed patients – such as this patient – followed by stem-cell collection in all patients (Figure 2). Then there is a randomization to either early high-dose therapy, melphalan, and autologous stem-cell transplantation, followed by lenalidomide maintenance; or in the other cohort, harvesting of stem cells, additional RVD, and then maintenance with lenalidomide, saving the stem-cell transplant for later.

The French portion of this trial was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier in 2017.7 It showed that patients who received RVD, high-dose melphalan, stem-cell transplant, and had 1 year of lenalidomide maintenance, had a progression-free survival advantage of about 1 year, without an overall survival advantage; compared with those patients who received RVD and lenalidomide maintenance, saving the transplant for later. I would hasten to add that lenalidomide maintenance was given for only 1 year in this trial, and patients in the RVD-only or RVD-and-transplant arms of this trial relapsed after the lenalidomide maintenance was discontinued.

The American portion of this trial is identical. That is, RVD induction is being given and all patients have a stem-cell collection. Half of the patients then go to high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant early, and half of them have the transplant only later at the time of relapse. A major difference, however, is that in both the RVD-only and RVD-and-transplant cohorts, patients receive lenalidomide maintenance until progression. This trial has been ongoing since 2009 and is still ongoing, which tells us that patients in both arms – the RVD-only as well as the RVD-and-transplant arms – are doing well.

In the recent STAMINA trial, all patients underwent a single high-dose therapy and transplant. Then there was a randomization to lenalidomide maintenance only in 1 cohort; a randomization to consolidation with RVD posttransplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the second cohort; or a randomization to a second high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the third cohort.8 I mention this because the outcomes in all 3 cohorts was similar.

I believe this tells us strongly that high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation twice – so-called tandem transplant – is no longer a major option in multiple myeloma. For now, however, in this patient, the standard of care would be to undergo induction therapy with triplet, novel combination treatment. Then, stem cells would be collected and high-dose therapy stem-cell transplant would be done, followed either by lenalidomide maintenance for standard disease or lenalidomide and bortezomib maintenance for high-risk disease. We won’t really know if we can delay transplant until the trials I’ve mentioned totally read out. In my clinical practice, if patients have had a major response to their induction therapy and have stem cells harvested, we can then offer them the opportunity to use maintenance therapy and save the transplant as a potential option for later, when myeloma relapses.

DR HENRY In summary then, this would be, in 2017, off-protocol while the data is pending: it’s reasonable to get a deep induction response, collect stem cells, have a discussion with the patient, and then consider high-dose therapy or not.

DR ANDERSON Yes. I think it’s reasonable to discuss it. We need to be open and honest with patients that the standard of care remains transplant, that you incorporate novel treatments before the transplant and novel treatments as maintenance after the transplant. The happy news is that the outcome, especially for patients who have standard-risk myeloma, is at least a decade or longer progression-free survival. It’s an optimistic picture. The data in terms of transplant being needed or not, will come within the next several years.

For now, it is a standard of care to use 1 high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant in this setting. I will add into our discussion with patients – besides the opportunity to harvest stem cells and think about whether one needs to do a transplant early on or not – is the issue of toxicity. High-dose melphalan by itself has a small but real secondary incidence of cancer, myelodysplasia, or leukemia. If one uses lenalidomide maintenance after melphalan transplantation treatment, that risk of secondary cancer is slightly increased.

In my experience, if patients have achieved a complete response with induction therapy only, it’s not unreasonable to offer early transplant and be clear that’s the standard of care. The alternative is maintenance with lenalidomide, knowing once the stem cells have been harvested, that transplantation can be an option to treat relapsed myeloma. We have many other options available as well. Time will tell in terms of the ongoing randomized trials as to whether transplant remains central to our treatment paradigm.

DR HENRY This leads us to our second patient. Here we have an older man of 74 years. He’s a professional piano player, so we want to try to avoid peripheral neuropathy in him. He has some mild renal insufficiency and some coronary artery disease, so he’s deemed transplant-ineligible. He has IgG kappa myeloma, and he’s brand new. What would you consider to be options for him for treatment?

DR ANDERSON This brings up the issue of a transplant-ineligible patient. He has significant comorbidity that would make transplantation an increased risk. What we would recommend in such a patient is still triplet induction therapy incorporating novel agents (Figure 1). Lenalidomide, the immunomodulatory drug, can safely be given in the context of neuropathy because it does not cause significant neuropathy. It would need to be dose modified, depending on the degree of renal insufficiency. We would recommend also including proteasome inhibitors. Bortezomib, the first-generation proteasome inhibitor, would be contraindicated because it does have a small but real attendant neuropathy. If, however, it is given weekly and subcutaneously, the risk of attendant neuropathy is quite low. In this patient, therefore, one could start with lenalidomide and bortezomib weekly and subcutaneously,1,2 with a very early and vigilant follow-up for the earliest signs of neuropathy, so as not to allow it to develop and compromise his career.

Alternatively, one could use a proteasome inhibitor that does not have attendant neuropathy. Carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, does not have neuropathy.9 But we would need to have caution here, because this patient has a history of coronary artery disease, and carfilzomib has a very small, but real, incidence of cardiac toxicity so would need to be used judiciously in this setting. The third proteasome inhibitor, ixazomib, is the next-generation bortezomib-class proteasome inhibitor, and it’s oral.10 It has less neuropathy than does bortezomib, so in my view is a very realistic option for him together with lenalidomide. It does have a small incidence of neuropathy, so close monitoring for neuropathy would be indicated. We could use lenalidomide–dexamethasone as a doublet and avoid neuropathy,11 but usually doublets are reserved only for frail patients.

My recommendation, therefore, would be RVD with the bortezomib weekly or subcutaneously, or alternatively, lenalidomide, ixazomib, dexamethasone as an all-oral regimen as induction therapy. In my view, this 74-year-old patient with comorbidity is not a transplant candidate. However, one can be very optimistic with this patient. The likelihood that he could have myeloma as a chronic illness and die from something else is quite high. Initial induction triplet therapy would achieve a very high response extent and frequency. The durability would be long, especially with lenalidomide maintenance if it’s standard-risk myeloma or lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, probably ixazomib in this setting, if he were to have high-risk myeloma.

If myeloma relapses, then there are many options that could be used in this patient and achieve years of progression-free and overall survival. Indeed, he is 74 years old and will respond very well to induction triplet therapy, with many years’ duration of response due to continuous lenalidomide or lenalidomide and proteasome inhibitor maintenance. Then there are many effective options to treat relapsed therapy using triplet novel agents. Therefore, his lifespan is unlikely to be shortened by multiple myeloma.

DR HENRY It’s so incredible compared with what it was when I trained. The next patient, a 45-year-old woman with IgG lambda myeloma, has had RVD induction and responded. She had lenalidomide maintenance, but then she progressed, and she got her stem-cell transplant, and she’s progressing after that. I guess we’re looking here to fold in some of the newer agents. How you would you do that in this patient?DR ANDERSON Yes. I think one of the most remarkable and exciting developments with myeloma is the rapid approval of the novel classes of agents that I mentioned earlier – the proteasome inhibitors, the immunomodulatory drugs, the HDAC inhibitor, and the monoclonal antibodies.1 They’re particularly relevant in a patient such as this one, whose myeloma has relapsed after what would be considered standard therapy for a young person with standard-risk myeloma. This patient had RVD and maintenance therapy, and then progressed. The transplant was given for relapsed myeloma. The opportunity to use stem-cell transplant in patients when myeloma becomes active after maintenance should not be forgotten as it can be very effective. In all the trials done to date in which early versus late transplant are compared, there have been similar outcomes. Therefore, if the transplant isn’t done early, don’t forget that it’s an option at the time the myeloma progresses. I do want to mention, that there are lots of options for relapsed myeloma (Figures 3 and 4). I mentioned RVD or CyBorD as initial triplet therapies.2-4 In North America, those are the 2 most common regimens. If myeloma then relapses and is resistant to RVD or to CyBorD, then we need to identify alternatives.

We also need to think about the comorbidities in the patient – issues such as age, neuropathy, presence of renal dysfunction, and other clinical factors. And we need to think about what treatment they’ve had in the past. This patient has had RVD, maintenance with lenalidomide, and a stem-cell transplant. We can offer patients a variety of therapies, but in the context of resistance to the first-generation proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and the first-generation immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide, we would strongly recommend the second-generation immunomodulatory drug pomalidomide12 together with a second-generation proteasome inhibitor, be that carfilzomib13 or ixazomib.14 When one uses the second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors together, there’s a very high frequency of response in the order of 70%-80%, which lasts years.

Besides carfilzomib and ixazomib proteasome inhibitors, we also have elotuzumab and daratumumab, the monoclonal antibodies.15-17 These agents have been FDA approved to treat patients such as this one who has had 1-3 previous therapies for their myeloma. All of them have been approved in randomized phase 3 trials compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone in the control arm.13-15,17 They’ve all been found to be superior. Although lenalidomide-dexamethasone combined with daratumumab, ixazomib, elotuzumab, or carfilzomib is superior to lenalidomide in relapsed myeloma, the situation in North America, as in this patient, is usually that patients have had lenalidomide-dexamethasone as part of their initial treatment and their myeloma is refractory to lenalidomide.

Hence, we recommend, that we go to the second-generation pomalidomide and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Having said that, the treatment paradigm is evolving. For example, the monoclonal antibody daratumumab was initially approved by the FDA in multiply relapsed disease as a single agent because it achieves a 30% response rate.16 It now has been moved earlier into the first relapse of multiple myeloma, where it achieves much higher response rates when combined with lenalidomide–dexamethasone or combined with bortezomib–dexamethasone.17,18 Response rates of 70%-80% can be achieved, including minimal residual disease negative complete responses.

Today, in a patient who has had RVD transplant and myeloma has returned, we would recommend second-generation IMiDs, pomalidomide, and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Data for daratumumab combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or with bortezomib-dexamethasone, look very promising. We need, however, to see more experience of daratumumab together with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or daratumumab together with bortezomib-dexamethasone in patients whose myeloma is refractory to RVD, that is, patients whose myeloma has returned after RVD induction treatment. Of note, pomalidomide, dexamethasone, and daratumumab have just been approved by the FDA and may also be active even in myeloma recurring after RVD treatment.19

Daratumumab in combination will be moving earlier and earlier and may be appropriate to treat the first relapse. I do want to stress, however, that at present I save daratumumab for the second or greater relapse. Daratumumab is active even when relapse occurs after treatment with second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors.

DR HENRY Before we close, I have a couple practical questions with these antibodies. Daratumumab has the track record of first-treatment severe reactions and long infusion times. How long are you anticipating the first daratumumab treatment takes? There has been some talk that maybe splitting it in half and going over 2 days is easier on the patient and the infusion center. Have you done that?

DR ANDERSON Yes, I think that’s a very important point. We need to be thinking – first and foremost – about efficacy of our therapy. Equally important, however, are the safety profile and the user-friendliness for the patient. Daratumumab infusions are quite long – on the order of 8 hours or longer on day 1 of infusion. And to date, all the clinical trials have used daratumumab infusions weekly for 8 treatments, followed by 8 treatments given every 2 weeks. Then monthly daratumumab is given as a maintenance therapy. Thus, there is a requirement for multiple outpatient clinic visits that can be prolonged.

One of the opportunities that’s being tested is to give daratumumab subcutaneously. While this is being evaluated in protocols now, the results that have been reported at our national meetings look to be quite promising in terms of efficacy, similar to results with the intravenous administration. Obviously, this would allow for a much more convenient clinic visit and shorter time for the patients being treated.

I should mention that the other antibody, elotuzumab, has been approved in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.15 The infusions with lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and the antibody elotuzumab are much shorter, on the order of 2- or 3-hour visits. The place for elotuzumab in the management of relapsed myeloma is yet to be totally defined. We tend to use it now in the setting of more indolent relapses, where patients might have a slowly rising monoclonal protein. Elotuzumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone has maintained an overall survival advantage at 4 years compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone when used in relapsed myeloma.

We are quite excited about both antibodies. Daratumumab tends to get most of the activity, as it achieves responses as a single agent,16 and the depth of the responses are markedly increased when it’s combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or bortezomib-dexamethasone.17,18 However, one shouldn’t forget elotuzumab15 based on its tolerability and the survival advantage I mentioned at 4 years.

The final point is that we think about myeloma genetically at the time of diagnosis and relapse in terms of standard or high-risk disease. One of the hallmarks of high-risk disease has been 17P deletion or P53 dysfunction. One of the most exciting outcomes of the development of monoclonal antibodies has been the responses observed even in the context of P53 deletion. Clearly, antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity, complement-mediated cytotoxicity, and other mechanisms of action of these antibodies do not require normal P53 function. The important point, therefore, is that what has previously been thought of as high-risk disease can nowadays be effectively treated with these new immune treatments, correlating with the marked improvement in survival and overall outcome.

DR HENRY We have outlined 3 kinds of myeloma patients we see, and especially interesting is the last patient, who has relapsed and then progressed, and in whom newer drugs have a role. Thank you for such a complete and thorough discussion, Dr Anderson.

DR HENRY I thought we might discuss some cases of patients with myeloma, starting with a relatively simple case and ending with one that is a little more complicated. For the first case, we have a 56-year-old healthy man with IgG kappa myeloma whose work-up shows he has multiple lytic bone lesions. He has normal renal function, normal calcium, and he’s transplant-eligible by other health issues. I’ll leave the cytogenetics up to you if that changes your approach. How would you develop or pose some options for this man’s treatment to begin with?

DR ANDERSON It’s important to start out by saying that we, in myeloma, have many new classes of drugs and many new opportunities to choose from to treat this patient.1 As you know, we have proteasome inhibitors, the first-generation bortezomib, then carfilzomib and ixazomib. We have the immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), thalidomide, and now lenalidomide and pomalidomide. We have a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved called panobinostat, and we have 2 monoclonal antibodies approved, elotuzumab and daratumumab. These classes of medicine have made it possible for 20 different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in the last 10-15 years. These agents, having been tested in advanced myeloma, have moved toward initial management.

This person is 50 years old. He has adequate liver, heart, lung, and kidney function, so he would be eligible for high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. In terms of initial management, there are many options (Figure 1). We strongly recommend that triplet therapy be used initially. The most common triplets would be lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD)2,3 or cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD).4 If this man had neuropathy, perhaps carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, with lenalidomide and dexamethasone could have been used. Why do we use these? The extent and frequency of response with these triplets is nearly universal overall response rate, with three-quarters very good partial and half-complete responses, including minimal residual disease negative responses. In this patient, we would therefore recommend treatment with either RVD or CyBorD for several cycles to maximal response.

He would then have autologous stem cells collected, and it is still the standard of care to proceed to high-dose melphalan and a single high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation. The cytogenetics are important: if this patient has standard-risk multiple myeloma, then lenalidomide maintenance would be given after transplant. It is now FDA-approved for this purpose because it can prolong both progression-free and – most importantly – overall survival.5 Standard-risk cytogenetics might, for example, include hyperdiploidy or translocation 11;14. On the other hand, if his myeloma were high-risk and characterized, for example, by 17p deletion, we would carry out the same induction and transplantation, but we would alter the maintenance to incorporate a proteasome inhibitor. Lenalidomide and bortezomib, for example, could be combined. Early data show that using combined maintenance therapy with lenalidomide and bortezomib, can overcome the early relapses that are characteristic of high-risk disease.6

Because of the extent and frequency of response to combination novel therapies, we have undertaken with our French colleagues a clinical trial of RVD in newly diagnosed patients – such as this patient – followed by stem-cell collection in all patients (Figure 2). Then there is a randomization to either early high-dose therapy, melphalan, and autologous stem-cell transplantation, followed by lenalidomide maintenance; or in the other cohort, harvesting of stem cells, additional RVD, and then maintenance with lenalidomide, saving the stem-cell transplant for later.

The French portion of this trial was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier in 2017.7 It showed that patients who received RVD, high-dose melphalan, stem-cell transplant, and had 1 year of lenalidomide maintenance, had a progression-free survival advantage of about 1 year, without an overall survival advantage; compared with those patients who received RVD and lenalidomide maintenance, saving the transplant for later. I would hasten to add that lenalidomide maintenance was given for only 1 year in this trial, and patients in the RVD-only or RVD-and-transplant arms of this trial relapsed after the lenalidomide maintenance was discontinued.

The American portion of this trial is identical. That is, RVD induction is being given and all patients have a stem-cell collection. Half of the patients then go to high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant early, and half of them have the transplant only later at the time of relapse. A major difference, however, is that in both the RVD-only and RVD-and-transplant cohorts, patients receive lenalidomide maintenance until progression. This trial has been ongoing since 2009 and is still ongoing, which tells us that patients in both arms – the RVD-only as well as the RVD-and-transplant arms – are doing well.

In the recent STAMINA trial, all patients underwent a single high-dose therapy and transplant. Then there was a randomization to lenalidomide maintenance only in 1 cohort; a randomization to consolidation with RVD posttransplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the second cohort; or a randomization to a second high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant followed by lenalidomide maintenance in the third cohort.8 I mention this because the outcomes in all 3 cohorts was similar.

I believe this tells us strongly that high-dose therapy and stem-cell transplantation twice – so-called tandem transplant – is no longer a major option in multiple myeloma. For now, however, in this patient, the standard of care would be to undergo induction therapy with triplet, novel combination treatment. Then, stem cells would be collected and high-dose therapy stem-cell transplant would be done, followed either by lenalidomide maintenance for standard disease or lenalidomide and bortezomib maintenance for high-risk disease. We won’t really know if we can delay transplant until the trials I’ve mentioned totally read out. In my clinical practice, if patients have had a major response to their induction therapy and have stem cells harvested, we can then offer them the opportunity to use maintenance therapy and save the transplant as a potential option for later, when myeloma relapses.

DR HENRY In summary then, this would be, in 2017, off-protocol while the data is pending: it’s reasonable to get a deep induction response, collect stem cells, have a discussion with the patient, and then consider high-dose therapy or not.

DR ANDERSON Yes. I think it’s reasonable to discuss it. We need to be open and honest with patients that the standard of care remains transplant, that you incorporate novel treatments before the transplant and novel treatments as maintenance after the transplant. The happy news is that the outcome, especially for patients who have standard-risk myeloma, is at least a decade or longer progression-free survival. It’s an optimistic picture. The data in terms of transplant being needed or not, will come within the next several years.

For now, it is a standard of care to use 1 high-dose melphalan and stem-cell transplant in this setting. I will add into our discussion with patients – besides the opportunity to harvest stem cells and think about whether one needs to do a transplant early on or not – is the issue of toxicity. High-dose melphalan by itself has a small but real secondary incidence of cancer, myelodysplasia, or leukemia. If one uses lenalidomide maintenance after melphalan transplantation treatment, that risk of secondary cancer is slightly increased.

In my experience, if patients have achieved a complete response with induction therapy only, it’s not unreasonable to offer early transplant and be clear that’s the standard of care. The alternative is maintenance with lenalidomide, knowing once the stem cells have been harvested, that transplantation can be an option to treat relapsed myeloma. We have many other options available as well. Time will tell in terms of the ongoing randomized trials as to whether transplant remains central to our treatment paradigm.

DR HENRY This leads us to our second patient. Here we have an older man of 74 years. He’s a professional piano player, so we want to try to avoid peripheral neuropathy in him. He has some mild renal insufficiency and some coronary artery disease, so he’s deemed transplant-ineligible. He has IgG kappa myeloma, and he’s brand new. What would you consider to be options for him for treatment?

DR ANDERSON This brings up the issue of a transplant-ineligible patient. He has significant comorbidity that would make transplantation an increased risk. What we would recommend in such a patient is still triplet induction therapy incorporating novel agents (Figure 1). Lenalidomide, the immunomodulatory drug, can safely be given in the context of neuropathy because it does not cause significant neuropathy. It would need to be dose modified, depending on the degree of renal insufficiency. We would recommend also including proteasome inhibitors. Bortezomib, the first-generation proteasome inhibitor, would be contraindicated because it does have a small but real attendant neuropathy. If, however, it is given weekly and subcutaneously, the risk of attendant neuropathy is quite low. In this patient, therefore, one could start with lenalidomide and bortezomib weekly and subcutaneously,1,2 with a very early and vigilant follow-up for the earliest signs of neuropathy, so as not to allow it to develop and compromise his career.

Alternatively, one could use a proteasome inhibitor that does not have attendant neuropathy. Carfilzomib, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor, does not have neuropathy.9 But we would need to have caution here, because this patient has a history of coronary artery disease, and carfilzomib has a very small, but real, incidence of cardiac toxicity so would need to be used judiciously in this setting. The third proteasome inhibitor, ixazomib, is the next-generation bortezomib-class proteasome inhibitor, and it’s oral.10 It has less neuropathy than does bortezomib, so in my view is a very realistic option for him together with lenalidomide. It does have a small incidence of neuropathy, so close monitoring for neuropathy would be indicated. We could use lenalidomide–dexamethasone as a doublet and avoid neuropathy,11 but usually doublets are reserved only for frail patients.

My recommendation, therefore, would be RVD with the bortezomib weekly or subcutaneously, or alternatively, lenalidomide, ixazomib, dexamethasone as an all-oral regimen as induction therapy. In my view, this 74-year-old patient with comorbidity is not a transplant candidate. However, one can be very optimistic with this patient. The likelihood that he could have myeloma as a chronic illness and die from something else is quite high. Initial induction triplet therapy would achieve a very high response extent and frequency. The durability would be long, especially with lenalidomide maintenance if it’s standard-risk myeloma or lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, probably ixazomib in this setting, if he were to have high-risk myeloma.

If myeloma relapses, then there are many options that could be used in this patient and achieve years of progression-free and overall survival. Indeed, he is 74 years old and will respond very well to induction triplet therapy, with many years’ duration of response due to continuous lenalidomide or lenalidomide and proteasome inhibitor maintenance. Then there are many effective options to treat relapsed therapy using triplet novel agents. Therefore, his lifespan is unlikely to be shortened by multiple myeloma.

DR HENRY It’s so incredible compared with what it was when I trained. The next patient, a 45-year-old woman with IgG lambda myeloma, has had RVD induction and responded. She had lenalidomide maintenance, but then she progressed, and she got her stem-cell transplant, and she’s progressing after that. I guess we’re looking here to fold in some of the newer agents. How you would you do that in this patient?DR ANDERSON Yes. I think one of the most remarkable and exciting developments with myeloma is the rapid approval of the novel classes of agents that I mentioned earlier – the proteasome inhibitors, the immunomodulatory drugs, the HDAC inhibitor, and the monoclonal antibodies.1 They’re particularly relevant in a patient such as this one, whose myeloma has relapsed after what would be considered standard therapy for a young person with standard-risk myeloma. This patient had RVD and maintenance therapy, and then progressed. The transplant was given for relapsed myeloma. The opportunity to use stem-cell transplant in patients when myeloma becomes active after maintenance should not be forgotten as it can be very effective. In all the trials done to date in which early versus late transplant are compared, there have been similar outcomes. Therefore, if the transplant isn’t done early, don’t forget that it’s an option at the time the myeloma progresses. I do want to mention, that there are lots of options for relapsed myeloma (Figures 3 and 4). I mentioned RVD or CyBorD as initial triplet therapies.2-4 In North America, those are the 2 most common regimens. If myeloma then relapses and is resistant to RVD or to CyBorD, then we need to identify alternatives.

We also need to think about the comorbidities in the patient – issues such as age, neuropathy, presence of renal dysfunction, and other clinical factors. And we need to think about what treatment they’ve had in the past. This patient has had RVD, maintenance with lenalidomide, and a stem-cell transplant. We can offer patients a variety of therapies, but in the context of resistance to the first-generation proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and the first-generation immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide, we would strongly recommend the second-generation immunomodulatory drug pomalidomide12 together with a second-generation proteasome inhibitor, be that carfilzomib13 or ixazomib.14 When one uses the second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors together, there’s a very high frequency of response in the order of 70%-80%, which lasts years.

Besides carfilzomib and ixazomib proteasome inhibitors, we also have elotuzumab and daratumumab, the monoclonal antibodies.15-17 These agents have been FDA approved to treat patients such as this one who has had 1-3 previous therapies for their myeloma. All of them have been approved in randomized phase 3 trials compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone in the control arm.13-15,17 They’ve all been found to be superior. Although lenalidomide-dexamethasone combined with daratumumab, ixazomib, elotuzumab, or carfilzomib is superior to lenalidomide in relapsed myeloma, the situation in North America, as in this patient, is usually that patients have had lenalidomide-dexamethasone as part of their initial treatment and their myeloma is refractory to lenalidomide.

Hence, we recommend, that we go to the second-generation pomalidomide and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Having said that, the treatment paradigm is evolving. For example, the monoclonal antibody daratumumab was initially approved by the FDA in multiply relapsed disease as a single agent because it achieves a 30% response rate.16 It now has been moved earlier into the first relapse of multiple myeloma, where it achieves much higher response rates when combined with lenalidomide–dexamethasone or combined with bortezomib–dexamethasone.17,18 Response rates of 70%-80% can be achieved, including minimal residual disease negative complete responses.

Today, in a patient who has had RVD transplant and myeloma has returned, we would recommend second-generation IMiDs, pomalidomide, and second-generation proteasome inhibitors, either carfilzomib or ixazomib. Data for daratumumab combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or with bortezomib-dexamethasone, look very promising. We need, however, to see more experience of daratumumab together with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or daratumumab together with bortezomib-dexamethasone in patients whose myeloma is refractory to RVD, that is, patients whose myeloma has returned after RVD induction treatment. Of note, pomalidomide, dexamethasone, and daratumumab have just been approved by the FDA and may also be active even in myeloma recurring after RVD treatment.19

Daratumumab in combination will be moving earlier and earlier and may be appropriate to treat the first relapse. I do want to stress, however, that at present I save daratumumab for the second or greater relapse. Daratumumab is active even when relapse occurs after treatment with second-generation IMiDs and proteasome inhibitors.

DR HENRY Before we close, I have a couple practical questions with these antibodies. Daratumumab has the track record of first-treatment severe reactions and long infusion times. How long are you anticipating the first daratumumab treatment takes? There has been some talk that maybe splitting it in half and going over 2 days is easier on the patient and the infusion center. Have you done that?

DR ANDERSON Yes, I think that’s a very important point. We need to be thinking – first and foremost – about efficacy of our therapy. Equally important, however, are the safety profile and the user-friendliness for the patient. Daratumumab infusions are quite long – on the order of 8 hours or longer on day 1 of infusion. And to date, all the clinical trials have used daratumumab infusions weekly for 8 treatments, followed by 8 treatments given every 2 weeks. Then monthly daratumumab is given as a maintenance therapy. Thus, there is a requirement for multiple outpatient clinic visits that can be prolonged.

One of the opportunities that’s being tested is to give daratumumab subcutaneously. While this is being evaluated in protocols now, the results that have been reported at our national meetings look to be quite promising in terms of efficacy, similar to results with the intravenous administration. Obviously, this would allow for a much more convenient clinic visit and shorter time for the patients being treated.

I should mention that the other antibody, elotuzumab, has been approved in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.15 The infusions with lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and the antibody elotuzumab are much shorter, on the order of 2- or 3-hour visits. The place for elotuzumab in the management of relapsed myeloma is yet to be totally defined. We tend to use it now in the setting of more indolent relapses, where patients might have a slowly rising monoclonal protein. Elotuzumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone has maintained an overall survival advantage at 4 years compared with lenalidomide-dexamethasone when used in relapsed myeloma.

We are quite excited about both antibodies. Daratumumab tends to get most of the activity, as it achieves responses as a single agent,16 and the depth of the responses are markedly increased when it’s combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone or bortezomib-dexamethasone.17,18 However, one shouldn’t forget elotuzumab15 based on its tolerability and the survival advantage I mentioned at 4 years.

The final point is that we think about myeloma genetically at the time of diagnosis and relapse in terms of standard or high-risk disease. One of the hallmarks of high-risk disease has been 17P deletion or P53 dysfunction. One of the most exciting outcomes of the development of monoclonal antibodies has been the responses observed even in the context of P53 deletion. Clearly, antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity, complement-mediated cytotoxicity, and other mechanisms of action of these antibodies do not require normal P53 function. The important point, therefore, is that what has previously been thought of as high-risk disease can nowadays be effectively treated with these new immune treatments, correlating with the marked improvement in survival and overall outcome.

DR HENRY We have outlined 3 kinds of myeloma patients we see, and especially interesting is the last patient, who has relapsed and then progressed, and in whom newer drugs have a role. Thank you for such a complete and thorough discussion, Dr Anderson.

1. Kumar SK, Callander NS, Alsina M, et al. Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:230-269.

2. Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:679-686.

3. Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777: a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):519-527.

4. Moreau P, Hulin C, Macro M, et al. VTD is superior to VCD prior to intensive therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the prospective IFM2013-04 trial. Blood. 2016;127:2569-2574.

5. McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. A phase III study of lenalidomide after transplant for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770-1781.

6. Nooka AK, Kaufman JL, Muppidi S, et al. Consolidation and maintenance therapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) in high risk myeloma patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:690-693.

7. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone with transplantation in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311-1320.

8. Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Comparison of autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT), bortezomib, lenalidomide (len) and dexamethasone (RVD) consolidation with len maintenance (ACM), tandem autohct with len maintenance (TAM) and autohct with len maintenance (AM) for up-front treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM): primary results from the randomized phase III trial of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN 0702 – StaMINA Trial). Abstract LBA-1. Presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, December 6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

9. Dytfeld D, Jasielec J, Griffith KA, et al: Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2014;99:e162-164.

10. Kumar SK, Berdeja JG, Niesvizky R, et al. Safety and tolerability of ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: an open-label phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1503-1512

11. Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. for the FIRST Trial Team. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917.

12. Richardson P, Siegel D, Vij R, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 2 study. Blood. 2014;123:1826-1832.

13. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. for the ASPIRE Investigators. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:142-152

14. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. for the TOURMALINE-MM1 Study Group. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;28;374:1621-1634.

15. Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. for the ELOQUENT-2 Investigators. Elotuzumab therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:621-631.

16. Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD 38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1207-1219.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1319-1331.

18. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. for the CASTOR Investigators. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:754-766.

19. Chari A, Suvannasankha A, Fay JW, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130(8):974-981.

1. Kumar SK, Callander NS, Alsina M, et al. Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:230-269.

2. Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:679-686.

3. Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777: a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):519-527.

4. Moreau P, Hulin C, Macro M, et al. VTD is superior to VCD prior to intensive therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the prospective IFM2013-04 trial. Blood. 2016;127:2569-2574.

5. McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. A phase III study of lenalidomide after transplant for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770-1781.

6. Nooka AK, Kaufman JL, Muppidi S, et al. Consolidation and maintenance therapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) in high risk myeloma patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:690-693.

7. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone with transplantation in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311-1320.

8. Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Comparison of autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT), bortezomib, lenalidomide (len) and dexamethasone (RVD) consolidation with len maintenance (ACM), tandem autohct with len maintenance (TAM) and autohct with len maintenance (AM) for up-front treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM): primary results from the randomized phase III trial of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN 0702 – StaMINA Trial). Abstract LBA-1. Presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, December 6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

9. Dytfeld D, Jasielec J, Griffith KA, et al: Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2014;99:e162-164.

10. Kumar SK, Berdeja JG, Niesvizky R, et al. Safety and tolerability of ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: an open-label phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1503-1512

11. Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. for the FIRST Trial Team. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917.

12. Richardson P, Siegel D, Vij R, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 2 study. Blood. 2014;123:1826-1832.

13. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. for the ASPIRE Investigators. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:142-152

14. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. for the TOURMALINE-MM1 Study Group. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;28;374:1621-1634.

15. Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. for the ELOQUENT-2 Investigators. Elotuzumab therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:621-631.

16. Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD 38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1207-1219.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1319-1331.

18. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. for the CASTOR Investigators. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:754-766.

19. Chari A, Suvannasankha A, Fay JW, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130(8):974-981.

Treating immunotherapy-related AEs in the emergency department

In this interview, Dr David Henry and Dr Maura Sammon discuss some of the most common immunotherapy-related side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and Dr Sammon describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. However, the overarching takeaway is the importance of communication: first, between the oncologist and patient, so that the patient is aware of these nuances in advance of an emergency, and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist soon after the patient has presented and undergone an initial assessment.

Dr Henry is Editor-in-Chief of the JCSO, and Dr Sammon is at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Listen here:

In this interview, Dr David Henry and Dr Maura Sammon discuss some of the most common immunotherapy-related side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and Dr Sammon describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. However, the overarching takeaway is the importance of communication: first, between the oncologist and patient, so that the patient is aware of these nuances in advance of an emergency, and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist soon after the patient has presented and undergone an initial assessment.

Dr Henry is Editor-in-Chief of the JCSO, and Dr Sammon is at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Listen here:

In this interview, Dr David Henry and Dr Maura Sammon discuss some of the most common immunotherapy-related side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and Dr Sammon describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. However, the overarching takeaway is the importance of communication: first, between the oncologist and patient, so that the patient is aware of these nuances in advance of an emergency, and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist soon after the patient has presented and undergone an initial assessment.

Dr Henry is Editor-in-Chief of the JCSO, and Dr Sammon is at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Listen here:

Gastrointestinal cancers: new standards of care from landmark trials

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and Dr Daniel Haller, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, discuss the findings from recent groundbreaking studies in gastrointestinal cancers.

Listen to the podcast below.

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and Dr Daniel Haller, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, discuss the findings from recent groundbreaking studies in gastrointestinal cancers.

Listen to the podcast below.

In this interview, Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and Dr Daniel Haller, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, discuss the findings from recent groundbreaking studies in gastrointestinal cancers.

Listen to the podcast below.

Gastrointestinal cancers: new standards of care from landmark trials

DR HENRY I am Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of

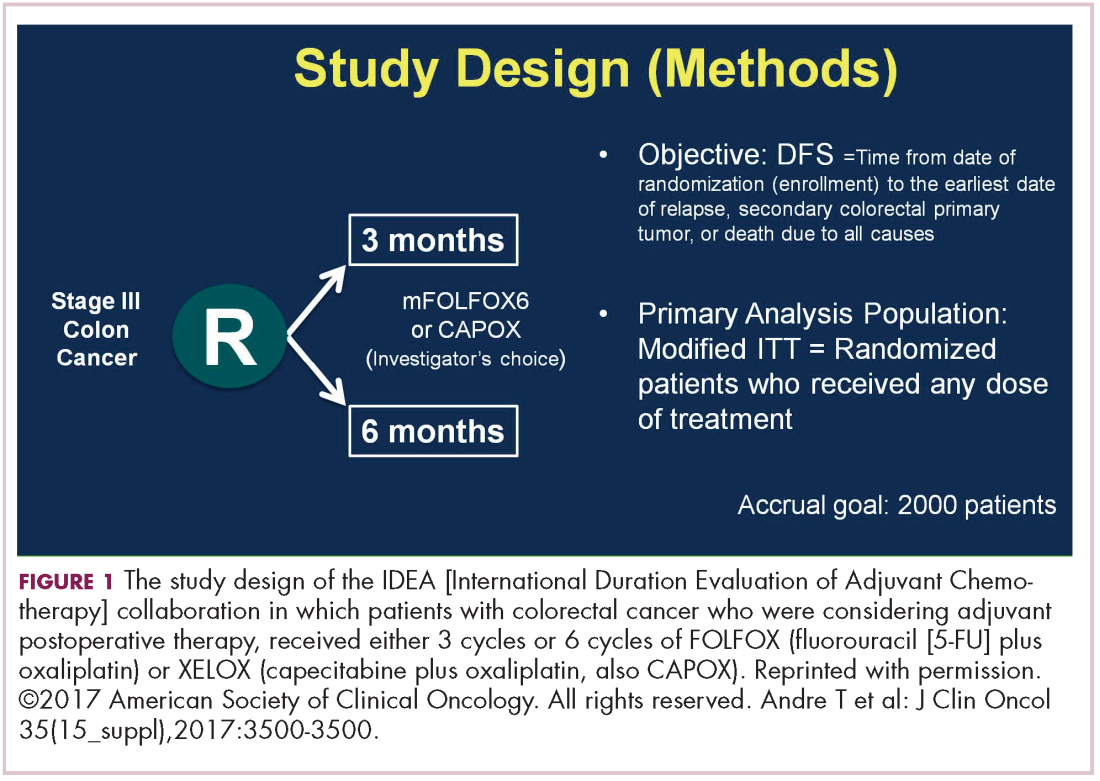

DR HALLER The IDEA collaboration was the brainchild of the late Dan Sargent, a biostatistician who was at the Mayo Clinic. It was his idea, since 6 international groups were all testing the same question of 3 months for oxaliplatin to 6 months of oxaliplatin, to combine the data in an individual patient database – which is the best way to do it – so there were these six trials that were all completed.