User login

Lithium and kidney disease: Understand the risks

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

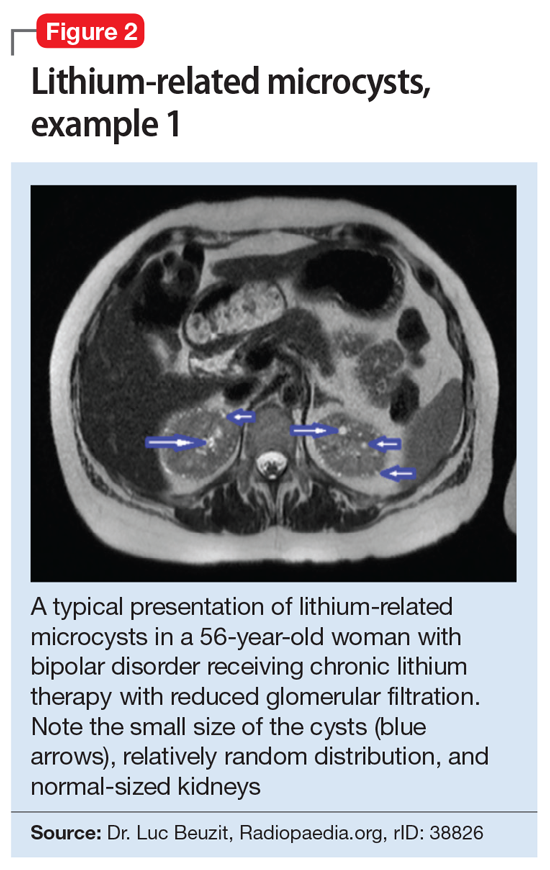

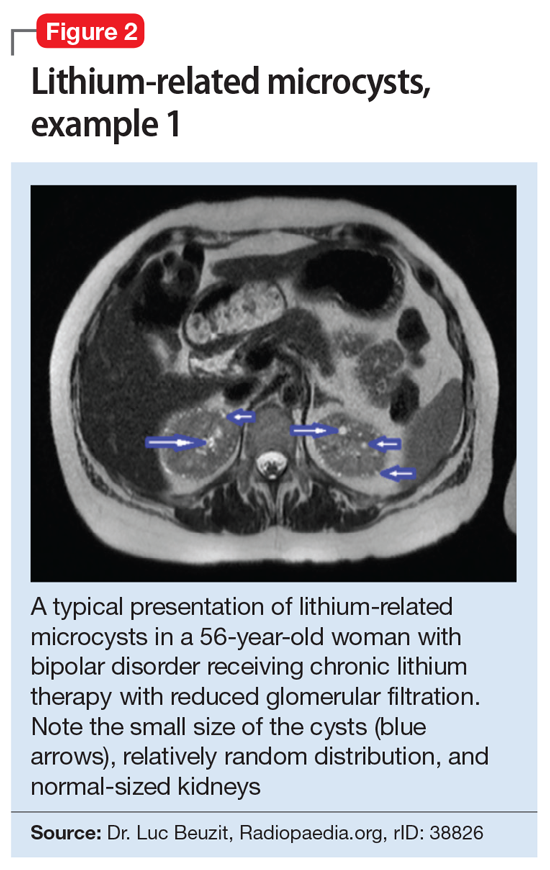

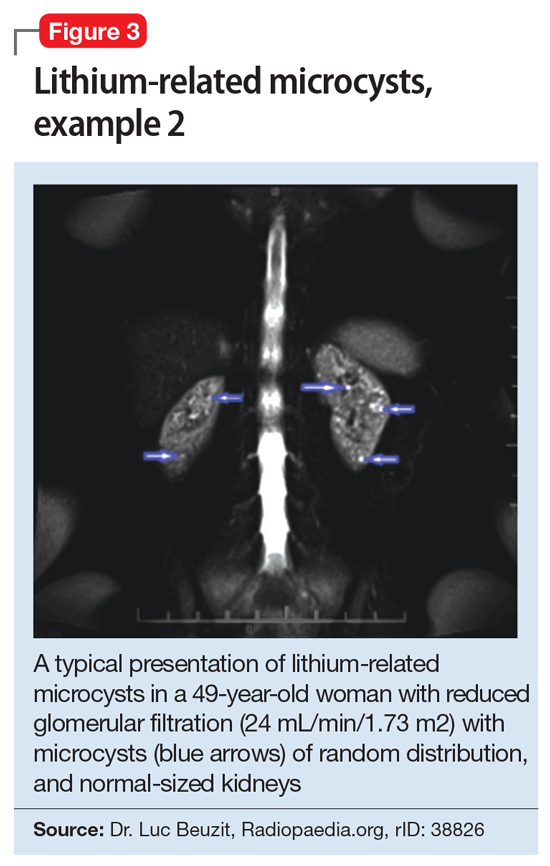

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

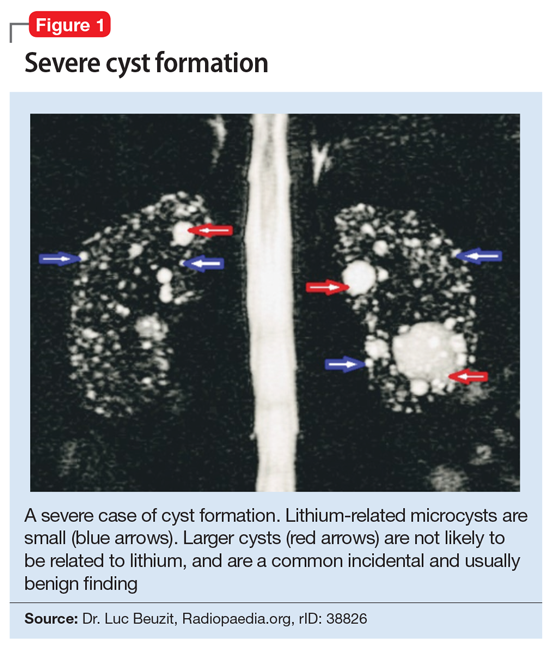

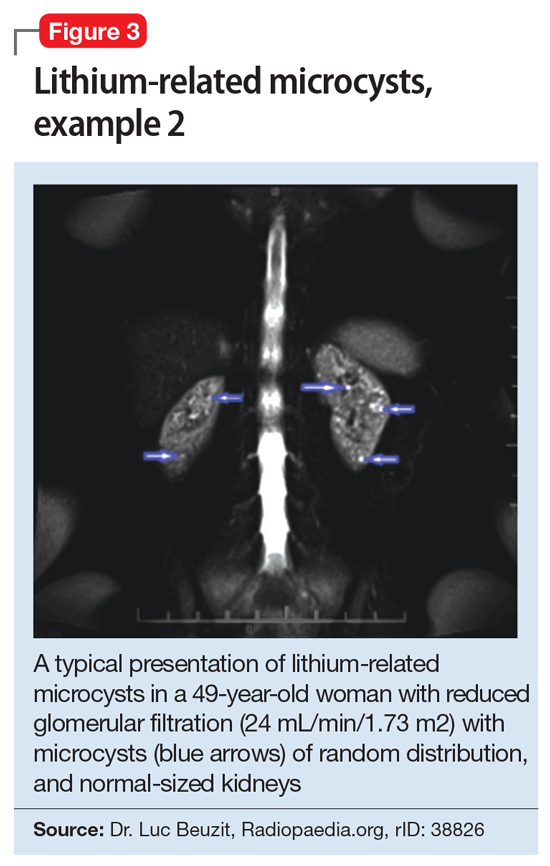

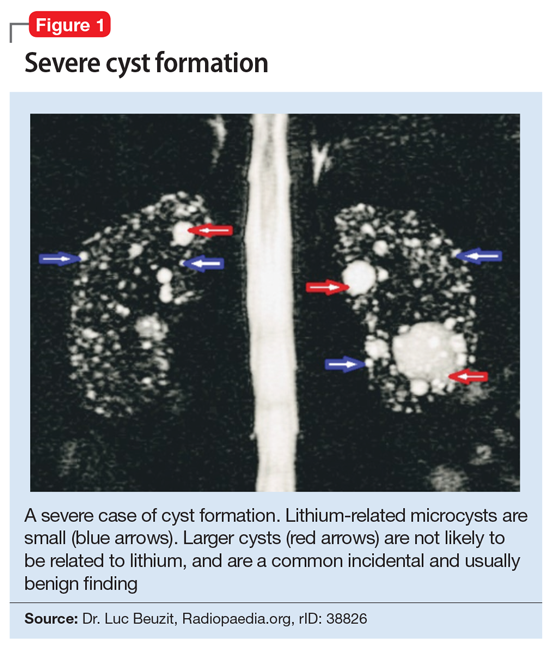

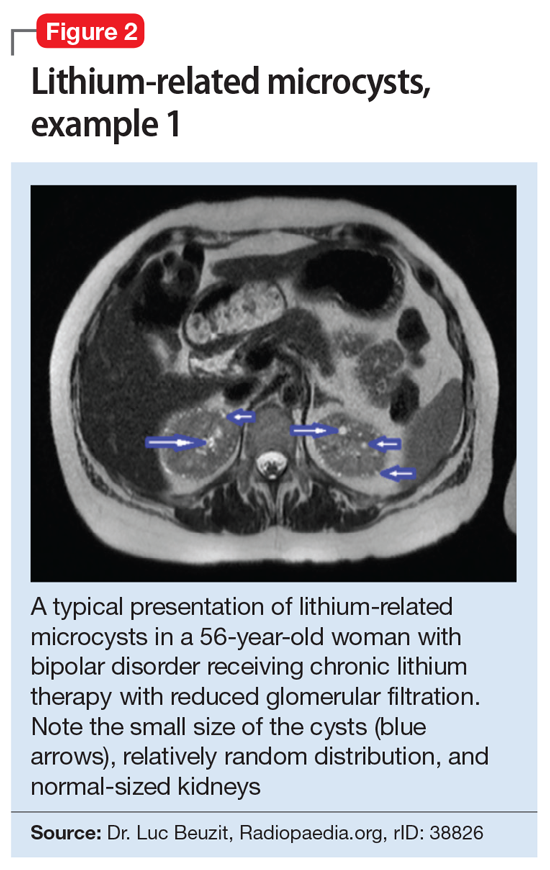

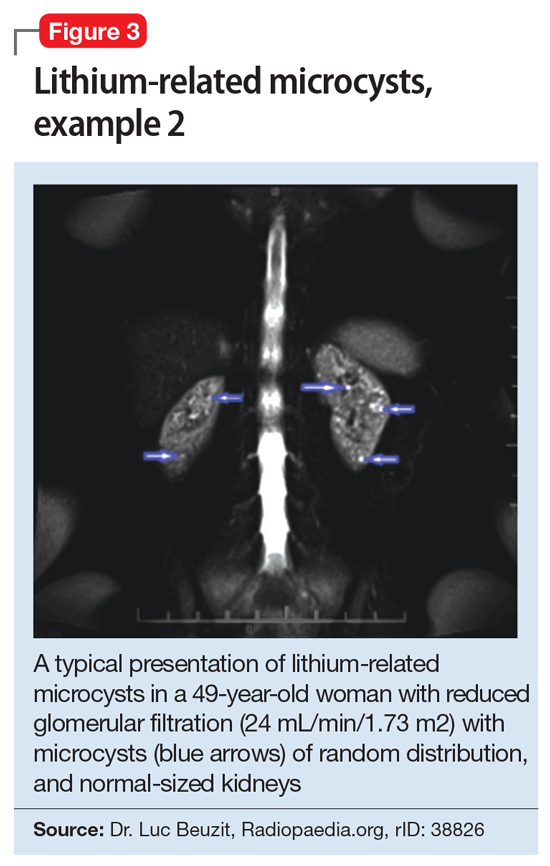

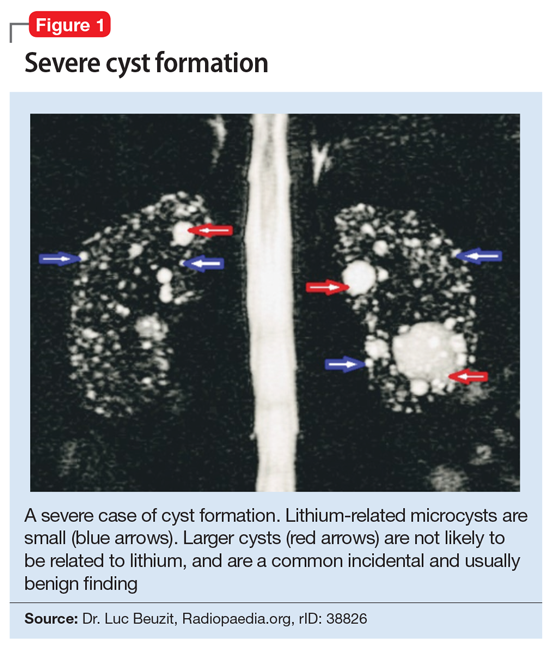

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

Posttraumatic stress disorder: From pathophysiology to pharmacology

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occurs acutely and chronically in the aftermath of severe and potentially life-threatening trauma.1 The prevalence of PTSD varies significantly across countries and by type of trauma (Box1-7).

Box

In the general population, the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) varies from as low as 0.3% in China to as high as 6.1% in New Zealand1 and 6.8% in the United States.2 These rates are actually much lower than expected when one considers that severe trauma is experienced by 60.7% of men and 51.2% of women.3,4 Although the majority of individuals exposed to trauma experience emotional distress immediately following a traumatic event, most of them do not develop PTSD.5

It appears that the context of trauma is important: 12% to 15% of veterans experience PTSD, compared with 19% to 75% of crime victims and 80% of rape victims.1 The lifetime risk for PTSD is twice as high in women as it is in men,6 and genetic vulnerability may play a role. For example, twin studies showed that approximately 30% of the risk for PTSD may be mediated by genetic predisposition.7

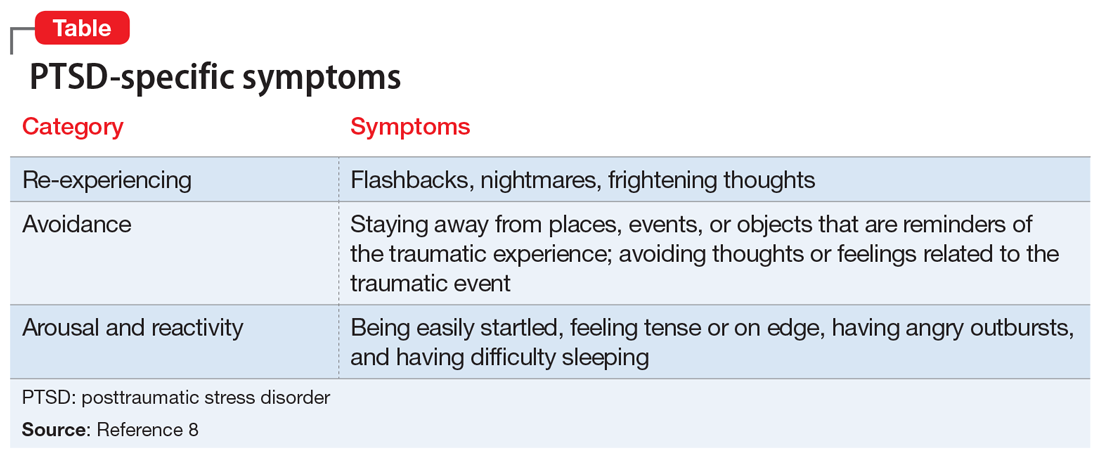

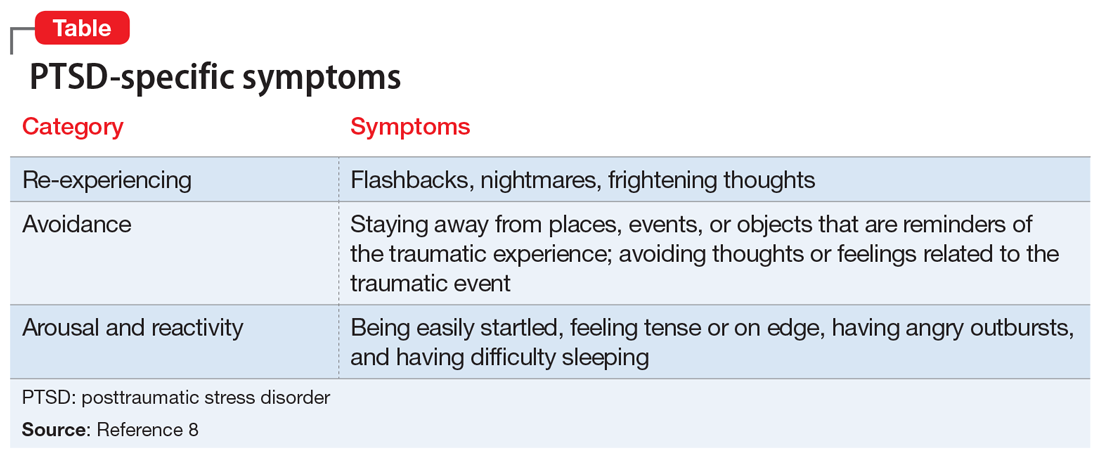

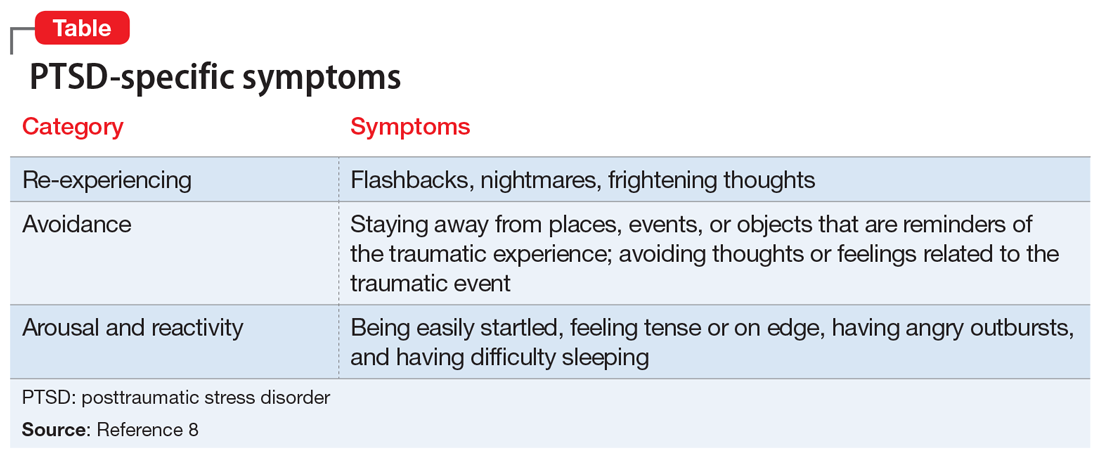

Individuals who develop PTSD experience a wide range of symptoms.8 These can be categorized as PTSD-specific symptoms, or nonspecific symptoms. PTSD-specific symptoms include nightmares, flashbacks, dissociative reactions, hyperreactivity or hyperarousal, distress with reminders of trauma, and avoidance of trauma-related physical reminders and thoughts/feelings (Table8). Nonspecific symptoms include depressive and anxiety symptoms and significant problems in social, relationship, or work situations.8

While successful treatment necessitates taking all of these symptoms into account, understanding the pathophysiology of PTSD can inform a more focused and rational treatment approach. In this article, we describe some key pathophysiologic PTSD studies, and focus on PTSD-specific psychopathology to inform treatment.

Brain systems implicated in PTSD

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is an anxiolytic endogenous peptide that has connections to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Its levels can be modulated by stress.9 Preclinical and clinical studies strongly support a potential role of NPY dysfunction in the pathophysiology of PTSD. Lower concentrations of NPY increase susceptibility to PTSD in combat veterans10 and in animal models.11 Three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) appear to mediate this effect.12 These findings strongly support pharmaceutical targeting this system as a useful therapeutic approach.13,14 Indeed, intranasal NPY administered as a single dose reduces anxiety in animal models15 and in humans,16 but this work has not yet translated into clinical tools.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor (CRHR1) gene. Corticotropin-releasing hormone has been implicated in PTSD.17 Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors (CRHR) are important mediators in response to stress.18,19 They bind corticotropin-releasing hormone and contribute to the integration of autonomic, behavioral, and immune responses to stress.20 Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the regulatory portion of the CRHR1 gene are associated with an increased risk for depression in adults who have a history of child abuse.21

The CRHR1 receptor antagonist GSK561679 is an investigational agent for the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders.22 In exploratory studies,23,24 GSK561679 was found to inhibit fear-potentiated startle in patients with PTSD, but not overall PTSD symptoms, although a subset of women with a specific genetic variant of the CRHR1 gene (rs110402) experienced significant benefit.25,26 This suggests that we must learn more about this system before we proceed.27

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The synthesis of BDNF is influenced by neuronal activity in the brain and plays a role in synaptic transmission and plasticity.28 Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is encoded by the BDNF gene, which has been implicated in stress vulnerability.29 A common SNP in the pro-region of the human BDNF gene results in a valine-to-methionine substitution at the 66th amino acid (Val66Met). The functional Val66Met polymorphism may have a role in the risk of developing PTSD. However, not all studies support this finding. One study found that an SNP with a resulting Val66Met polymorphism is associated with adult PTSD symptoms after childhood abuse, while a meta-analysis of 7 studies did not confirm this.30,31 We need to learn more about BDNF before we proceed.32

Continue to: Serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene

Serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene. Serotonin transporter is a monoamine transporter protein that terminates the neurotransmitter signal by transporting serotonin from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic neuron. It is encoded by the SLC6A4 gene, which resides on the long arm of chromosome 17(17q11.1-q12). It is a large gene with 31 kilo bases and 14 separate exons (transcribed regions).33,34

This gene has several variants. The best-studied is a variation in the promoter region. A 44-bp insertion or deletion yields the “long” and “short” alleles, respectively. The proteins produced by the 2 alleles are identical, but the amount of expressed protein is different. The short allele (“S”) is associated with a nearly 50% reduction in 5-HTT expression in both homozygotes and heterozygotes.35 A greater incidence of serotonin transporter promoter region (5-HTTLPR) S has been found in individuals with PTSD compared with those without PTSD,36-38 and 5-HTTLPR S increases the risk of PTSD in individuals with low social support39 or after very few traumatic events.40 The short allele variant is also associated with depression in individuals who face adversity.35,41

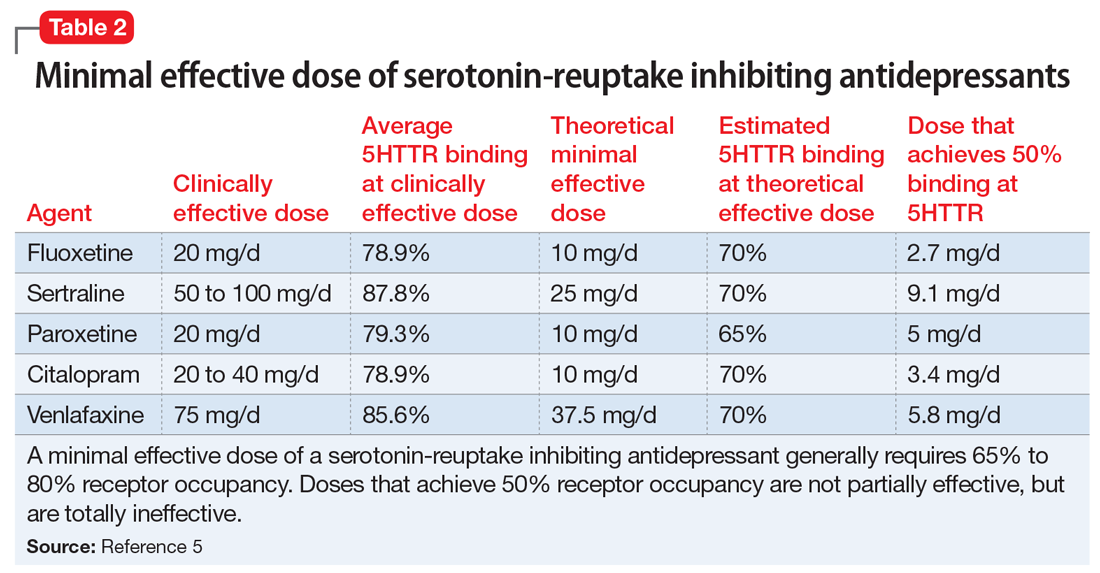

The overrepresentation of the short form of 5-HTTLPR in individuals who develop PTSD may represent a potential problem with current treatment paradigms, in which an antidepressant is the first-line treatment, because this allele is associated with reduced response to antidepressants.42,43 More distressing is the possible association of this allele with increased suicide risk, particularly violent suicide44 or repeated suicide attempts.45

Furthermore, a functional MRI study of patients who were anxious revealed that in individuals with the short allele, administration of

Catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) is one of the enzymes that degrades catecholamines such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine (NE).47 In humans, COMT protein is encoded by the COMT gene. This gene is associated with allelic variants; the best-studied of these is Val158Met. COMT Val158Met polymorphism (rs4860) has been linked to deficits in stress response and emotional resilience.48,49 Val158Met is associated with a 40% reduction in enzyme activity and slower catalysis of catecholamines, resulting in increases in catecholamines levels in the brain, which may increase the risk of developing PTSD.50 Individuals homozygous for this SNP (Met/Met) are highly susceptible to develop PTSD independently of the severity of the trauma they experienced.51 The Val158Met polymorphism may be associated with other abnormalities, such as cognitive problems with specific frontal cortical activity, and also with improved antidepressant response (valine homozygotes less responsive than methionine homozygotes).52 This gene is available on gene testing profiles.

Continue to: The role of norepinephrine in PTSD

The role of norepinephrine in PTSD

Perhaps the greatest advance in the understanding of the pathophysiology of PTSD relates to changes in brain NE. The HPA axis is responsible for coordinating the hormonal response to stress. Dysregulation of this axis and increased activity of the central and peripheral noradrenergic systems are usually observed in patients with PTSD.53 Several monoamine neurotransmitters are important in the regulation and function of the HPA axis. Norepinephrine plays a major role in stress.

The clinical PTSD-specific criteria are all descriptions of excessive noradrenergic tone.54 For example, hypervigilance and hyperstartle are clearly anticipated as evidence of NE stimulation. Flashbacks, particularly those that might be precipitated by environmental cues, also can be a manifestation of the vigilance induced by NE. Sleep disturbances (insomnia and nightmares) are present; insomnia is reported more often than nightmares.55 Increased catecholamine levels, particularly NE, are a feature of sleep disturbances associated with middle insomnia. Dreams can be remembered only if you wake up during dreaming. Catecholamines do not change the content of dreams, just recall.56

In a study of central noradrenergic tone in patients with PTSD, 6 hourly CSF samples were collected from 11 male combat veterans with PTSD and 8 healthy controls.57 Participants with PTSD had significantly higher CSF NE concentrations (0.55 ± 0.17 pmol/ml vs 0.39 ± 0.16 pmol/mL in the PTSD and control groups, respectively; F = 4.49, P < .05).57 Overall PTSD symptoms correlated significantly with CSF NE levels (r = 0.82, P <.005), and PTSD-specific symptoms such as avoidance (r = 0.79, P = .004). Intrusive thoughts (r = 0.57, P = .07) and hyperarousal (r = 0.54, P = .09) were also related.57 This relationship is unique; patients with PTSD with predominant depressive symptoms do not have elevated plasma NE levels.58

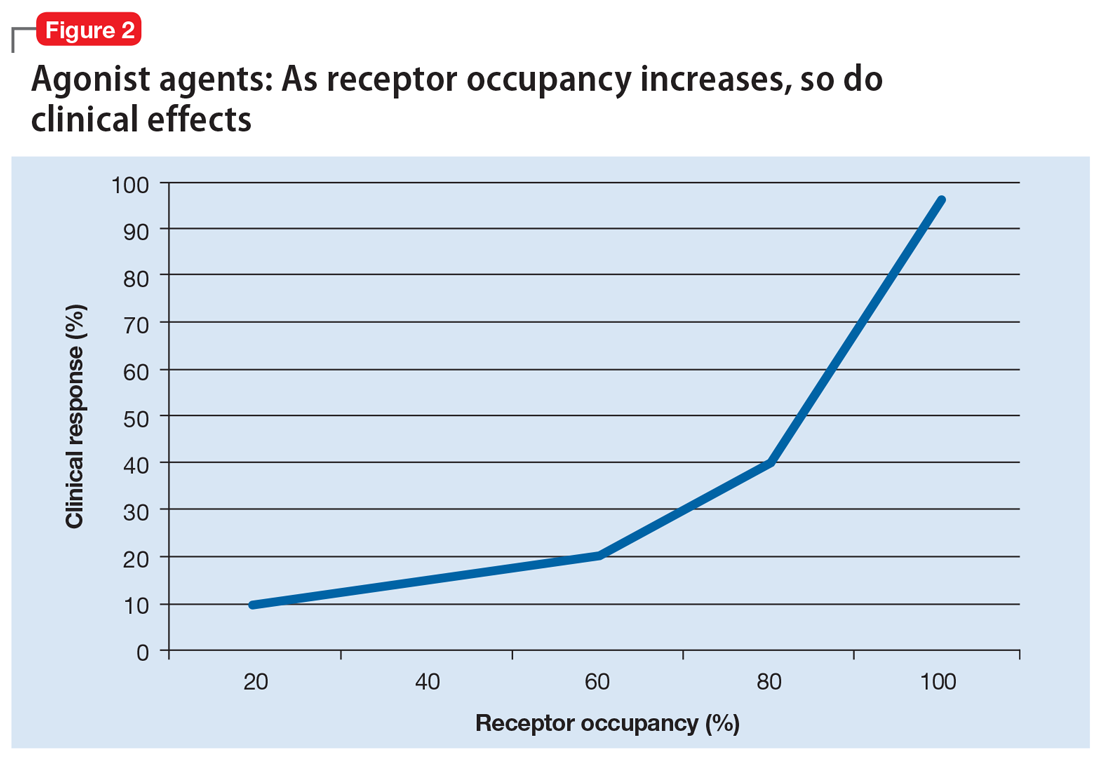

In the human brain, there are 3 main groups of NE receptors: alpha-1 receptors, alpha-2 receptors, and beta receptors.59 Alpha-1 receptors (alpha-1A, alpha-1B, and alpha-1D) are postsynaptic and mediate increase in inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and intracellular calcium (Ca2+). Alpha-2 receptors (alpha-2A, alpha-2B, alpha-2C) in the CNS are presynaptic autoreceptors and serve to reduce NE release. Beta receptors (beta-1, beta-2, beta-3) inhibit cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production.59 The effects of inhibition of alpha or beta receptors are different. Inhibition of beta receptors is associated with depressive symptoms and depressive syndrome, inhibition of peripheral beta receptors is associated with reductions in anxiety (generally reduction of pulse, sweating, tremor),60 and inhibition of central alpha-1 receptors is associated with reduced PTSD symptoms.61

Choice of agents for PTSD-specific symptoms

As outlined in the Table,8 PTSD is characterized by 3 types of symptoms that are specific for PTSD. Trauma-focused psychotherapy62,63 and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)64 are considered first-line therapy for PTSD. Only

Continue to: Serotonin transporter promoter...

Serotonin transporter promoter region gene short-type variants, which possibly increase an individual’s predisposition to developing PTSD, may explain the abundance of depressive symptoms in this condition and the subdued response to antidepressants. Specifically, an anticipated preponderance of these alleles may be associated with poorer outcomes. Non-SSRI treatments, such as low-dose

On the other hand, animal models support antagonism of the postsynaptic alpha-1 adrenergic receptor of the CNS as a target for PTSD treatment.71 Although

Quetiapine might be another non-SSRI option for treating patients with PTSD. It is an antagonist with high affinity tothehistamine-1 receptor at low doses. Norquetiapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that increases brain NE levels. Both quetiapine and norquetiapine are alpha-1 antagonists. There is no beta blockade and no SSRI effect, but some 5HT2A blockade, which may be anxiolytic. Compared with placebo, an average quetiapine dose of 258 mg/d resulted in significantly greater reductions in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale total score, re-experiencing score, and hyperarousal score.73

Unfortunately, none of the non-SSRI options have been adequately evaluated. For now, clinicians need to continue to use SSRIs, and researchers need to continue to explore mechanism-guided alternatives.

Bottom Line

Understanding the mechanisms of the pathophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may allow clinicians to “jump ahead” of clinical studies and FDA indications. Clinicians may reasonably use alpha-1 antagonists (eg, prazosin, quetiapine) for general clinical improvement of patients with PTSD, particularly for PTSD-specific symptoms. Using antihistamines to reduce anxiety (especially in patients who have the COMT Val158Met polymorphism) may also be reasonable.

Related Resources

- North CS, Hong BA, Downs DL. PTSD: a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):35-43.

- Zhang Y, Ren R, Sanford LD, et al. The effects of prazosin on sleep disturbances in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2019; 67:225-231.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Citalopram • Celexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Javidi H, Yadollahie M. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2012;3(1):2-9.

2. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

3. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060.

4. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):626-632.

5. Cerda M, Sagdeo A, Johnson J, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on psychiatric comorbidity: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1-2):14-38.

6. Yehuda R, Hoge CW, McFarlane AC, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15057. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.57.

7. True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(4):257-264.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:271-280.

9. Reichmann F, Holzer P. Neuropeptide Y: a stressful review. Neuropeptides. 2016;55:99-109.

10. Yehuda R, Brand S, Yang RK. Plasma neuropeptide Y concentrations in combat exposed veterans: relationship to trauma exposure, recovery from PTSD, and coping. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(7):660-663.

11. Cohen H, Liu T, Kozlovsky N, et al. The neuropeptide Y (NPY)-ergic system is associated with behavioral resilience to stress exposure in an animal model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(2):350-363.

12. Donner J, Sipilä T, Ripatti S, et al. Support for involvement of glutamate decarboxylase 1 and neuropeptide Y in anxiety susceptibility. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B(3):316-327.

13. Schmeltzer SN, Herman JP, Sah R. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a translational update. Exp Neurol. 2016;284(pt B):196-210.

14. Kautz M, Charney DS, Murrough JW. Neuropeptide Y, resilience, and PTSD therapeutics. Neurosci Lett. 2017;649:164-169.

15. Serova LI, Laukova M, Alaluf LG, et al. Intranasal neuropeptide Y reverses anxiety and depressive-like behavior impaired by single prolonged stress PTSD model. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(1):142-147.

16. Sayed S, Van Dam NT, Horn SR, et al. A randomized dose-ranging study of neuropeptide Y in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(1):3-11.

17. Toth M, Flandreau EI, Deslauriers J, et al. Overexpression of forebrain CRH during early life increases trauma susceptibility in adulthood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(6):1681-1690.

18. White S, Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Association of CRHR1 variants and posttraumatic stress symptoms in hurricane exposed adults. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(7):678-683.