User login

Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

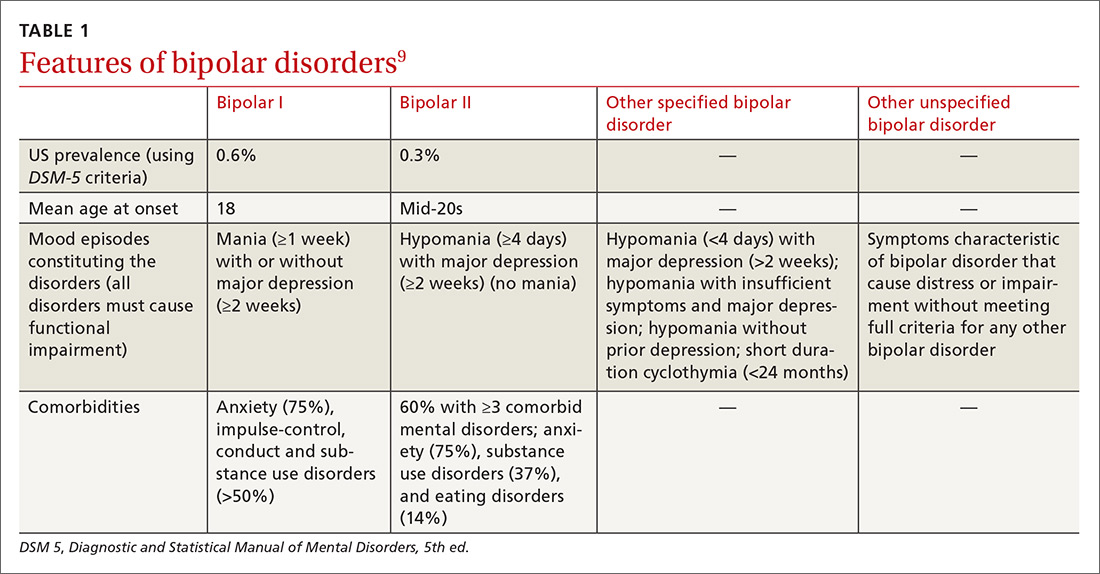

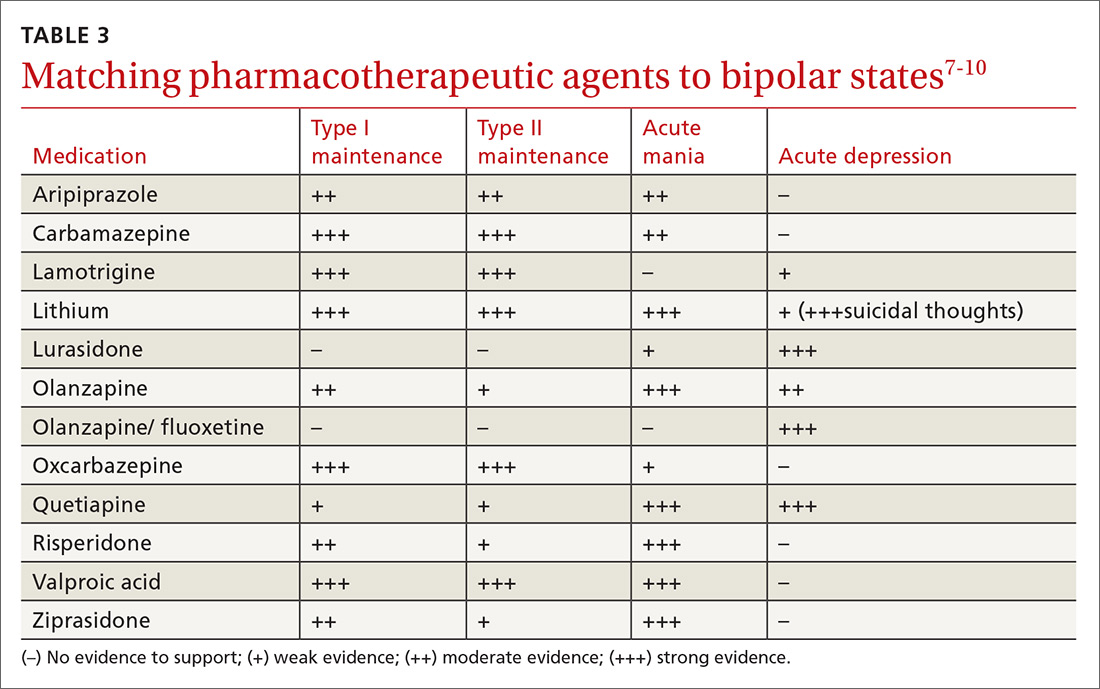

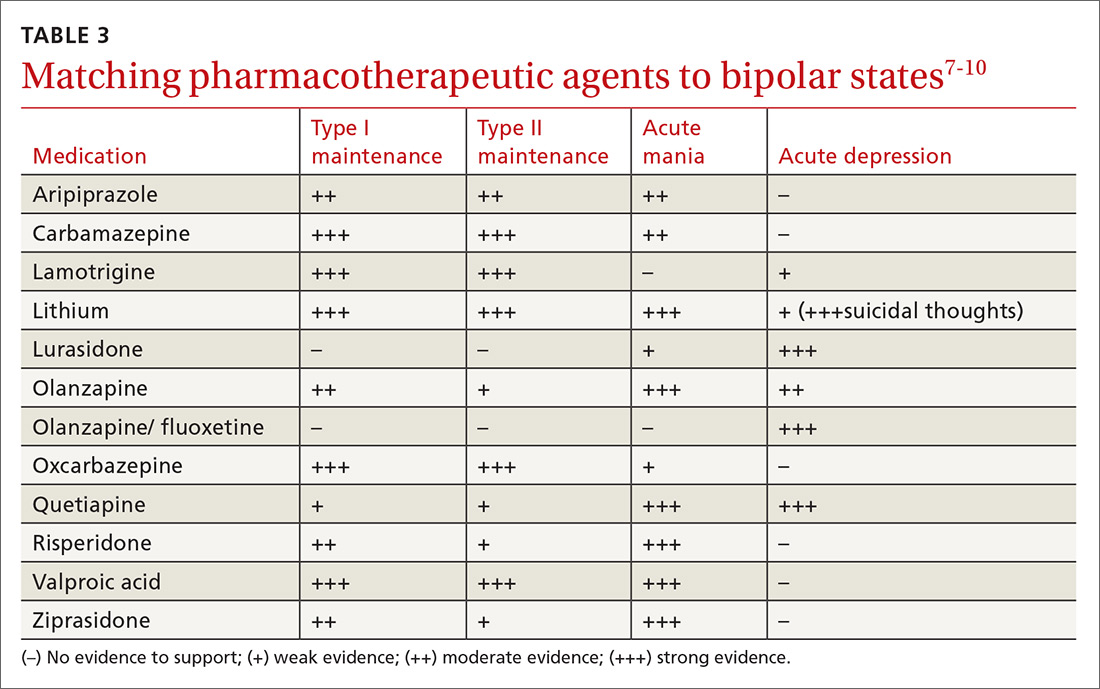

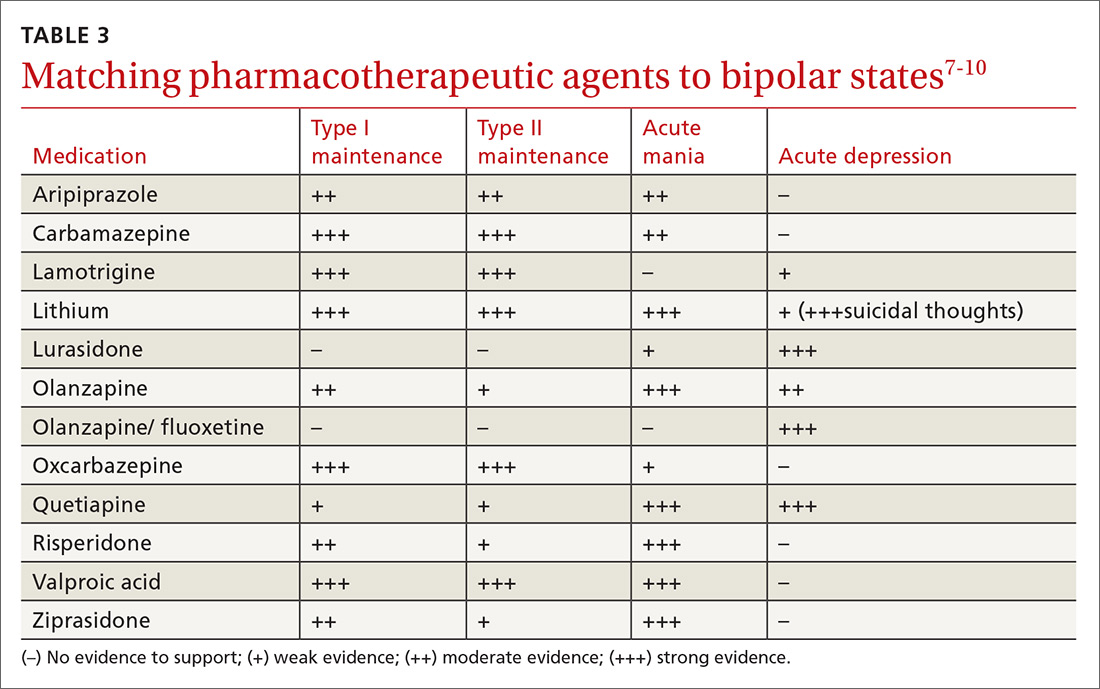

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; nyoussef@augusta.edu.

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

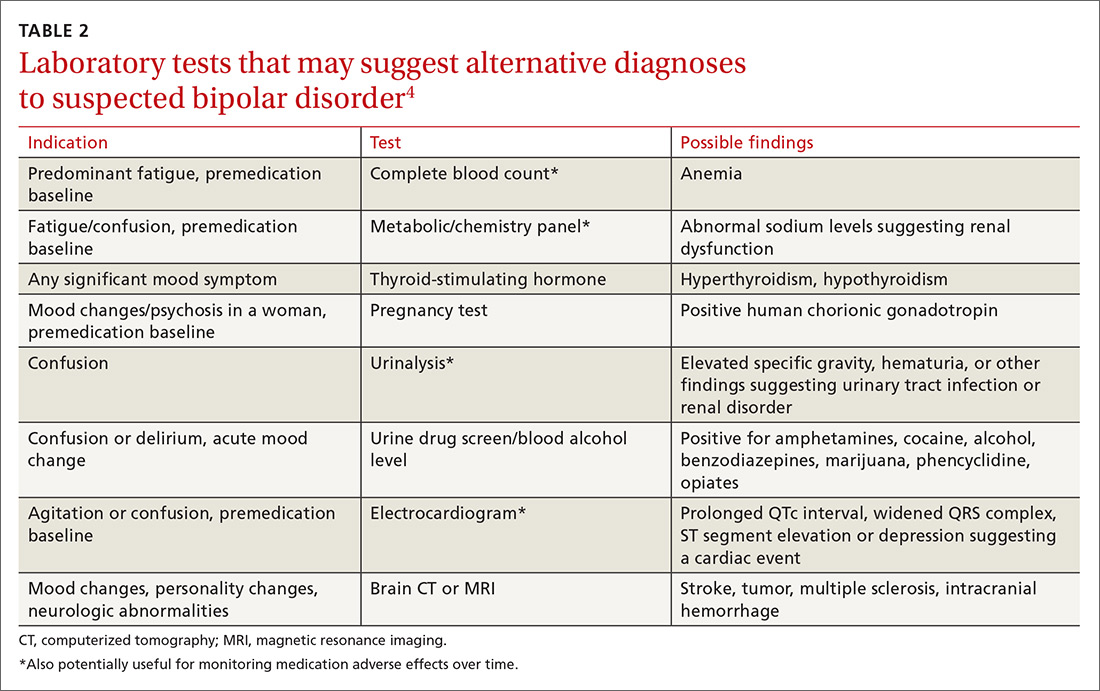

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; nyoussef@augusta.edu.

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; nyoussef@augusta.edu.

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.

Schizophrenia: Ensuring an accurate Dx, optimizing treatment

THE CASE

Steven R,* a 21-year-old man, visited the clinic accompanied by his mother. He did not speak much, and his mother provided his history. Over the previous 2 months, she had overheard him whispering in an agitated voice, even though no one else was nearby. And, lately, he refused to answer or make calls on his cell phone, claiming that if he did it would activate a deadly chip that had been implanted in his brain by evil aliens. He also stopped attending classes at the community college. He occasionally had a few beers with his friends, but he had never been known to abuse alcohol or use other recreational drugs.

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

CHARACTERISTICS AND SCOPE OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness in which the individual loses contact with reality and often experiences hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorders. Criteria for schizophrenia described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) include signs and symptoms of at least 6 months’ duration, as well as at least one month of active-phase positive and negative symptoms.1

Delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior are examples of positive symptoms. Negative symptoms include a decrease in the range and intensity of expressed emotions (ie, affective flattening) and a diminished initiation of goal-directed activities (ie, avolition).

Approximately 7 in 1000 people will develop the disorder in their lifetime.2 Schizophrenia is considered a “serious mental illness” because of its chronic course and often poor long-term social and vocational outcomes.3,4 Symptom onset is generally between late adolescence and the mid-30s.5

Getting closer to understanding its origin

Both genetic susceptibility and environmental factors influence the incidence of schizophrenia.4 Newer models of the disease have identified genes (ZDHHC8 and DTNBP1) whose mutations may increase the risk of schizophrenia.6 Physiologic insults during fetal life—hypoxia, maternal infection, maternal stress, and maternal malnutrition—account for a small portion of schizophrenia cases.6

Abnormalities in neurotransmission are the basis for theories on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Most of these theories center on either an excess or a deficiency of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. Other theories implicate aspartate, glycine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid as part of the neurochemical imbalance of schizophrenia.7

ESTABLISHING A DIAGNOSIS

Although psychotic symptoms may be a prominent part of schizophrenia, not all psychoses indicate a primary psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia. Broadly, psychoses can be categorized as primary or secondary.

Primary psychoses include schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and mood disorders (major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder) with psychotic features.1 Difficulty in distinguishing between these entities can necessitate referral to a psychiatrist.

Secondary psychoses arise from a precursor such as delirium, dementia, medical illness, or adverse effects of medications or illicit substances. Medical illnesses that cause psychotic symptoms include: 5,8

- seizures (especially temporal lobe epilepsy),

- cerebrovascular accidents,

- intracranial space-occupying lesions,

- neuropsychiatric disorders (eg, Wilson’s or Parkinson’s disease),

- endocrine disorders (eg, thyroid or adrenal disease),

- autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, Hashimoto encephalopathy),

- deficiencies of vitamins A, B1, B12, or niacin,

- infections (eg, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], encephalitis, parasites, and prion disease),

- narcolepsy, and

- metabolic disease (eg, acute intermittent porphyria, Tay-Sach’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease).

Several recreational drugs can cause psychotic symptoms: cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids, inhalants, opioids, and hallucinogens. Psychotic symptoms can also appear during withdrawal from alcohol (delirium tremens) and from sedative hypnotics such as benzodiazepines. Prescribed medications such as anticholinergics, corticosteroids, dopaminergic agents (L-dopa), stimulants (amphetamines), and interferons can also induce psychotic symptoms.

First rule out causes of secondary psychosis

Rule out causes of secondary psychosis by conducting a detailed history and physical examination and ordering appropriate lab tests and imaging studies. If the patient’s psychosis is of recent onset, make sure the laboratory work-up includes

Consider cranial computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging if there are focal neurologic deficits or if the patient’s presentation is atypical (eg, new onset psychosis in old age).9 Clinical presentation may also indicate a need for electroencephalography, ceruloplasmin measurement, a dexamethasone suppression test, a corticotropin stimulation test, 24-hour urine porphyrin and copper assays, chest radiography, or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.9

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN TREATMENT DECISIONS

Although primary care physicians may encounter individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis, it’s more likely that patients presenting with signs and symptoms of the disorder have been experiencing them for some time and have received no psychiatric care. In both instances, schizophrenia is best managed in conjunction with a psychiatrist until symptoms are stabilized.5 Psychosis does not always require hospitalization. But urgent psychiatry referral is recommended, if possible. Consider admission to a psychiatric inpatient unit for anyone who poses a danger to self or others.8,10

Treatment for schizophrenia is most effective with an interprofessional and collaborative approach that includes medication, psychological treatment, social supports, and primary care clinical management.11,12 The last aspect takes on particular importance given that people with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, have a higher incidence of medical illness, particularly cardiovascular disease.13

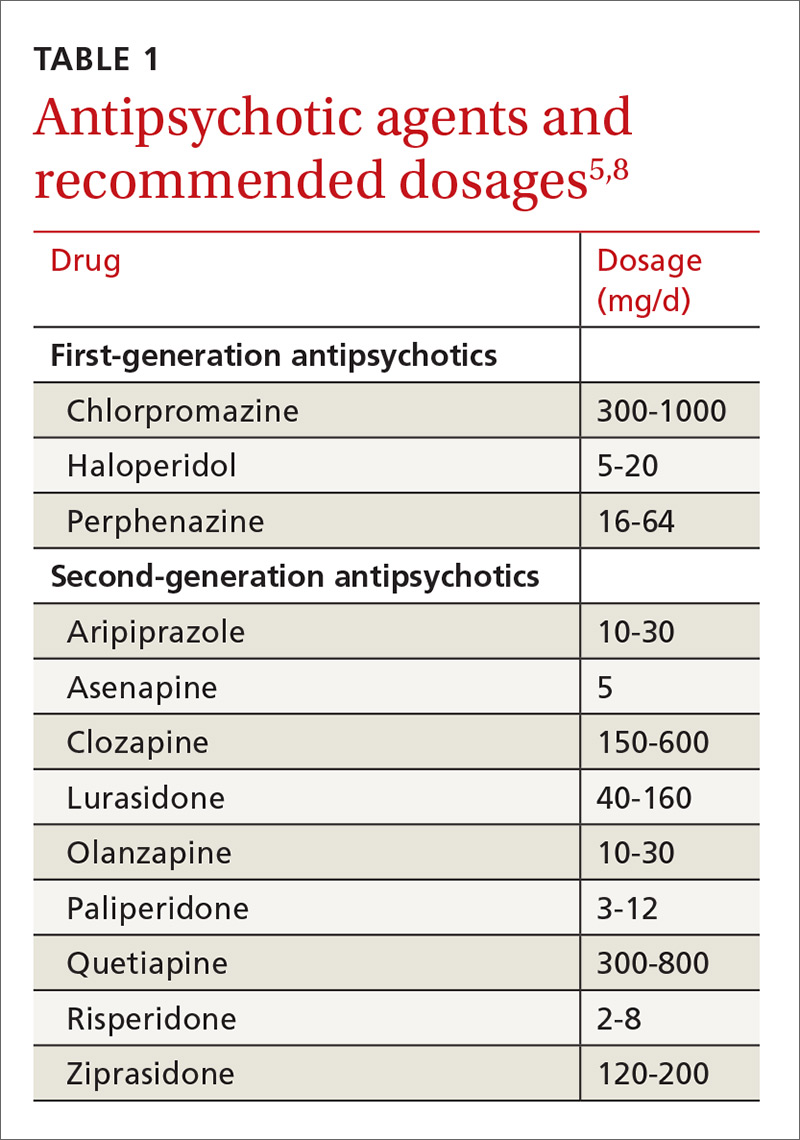

Medications (TABLE 15,8) are grouped into first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics (SGAs), with the 2 classes being equally effective.14-16 Quality of life is also similar at one year for patients treated with either drug class.14

Adverse effects can differ. The main difference between these medications is their adverse effect profiles. FGAs cause extrapyramidal symptoms (dystonia, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia) more often than SGAs. Among the SGAs, olanzapine, asenapine, paliperidone, clozapine, and quetiapine cause significant weight gain, glucose dysregulation, and lipid abnormalities.5,8,12,17 Clozapine is associated with agranulocytosis, as well. Risperidone causes mild to moderate weight gain.5,8,12,17 Aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone are considered weight neutral and cause no significant glucose dysregulation or lipid abnormalities.5,8,12,17 All antipsychotics can cause QT prolongation and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.5,8,12,17

Keys to successful treatment. Antipsychotics are most effective in treating positive symptoms of schizophrenia and show limited, if any, effect on negative or cognitive symptoms.18,19 Give patients an adequate trial of therapy (at least 4 weeks at a therapeutic dose) before discontinuing the drug or offering a different medication.20 All patients who report symptom relief while receiving antipsychotics should receive maintenance therapy.12

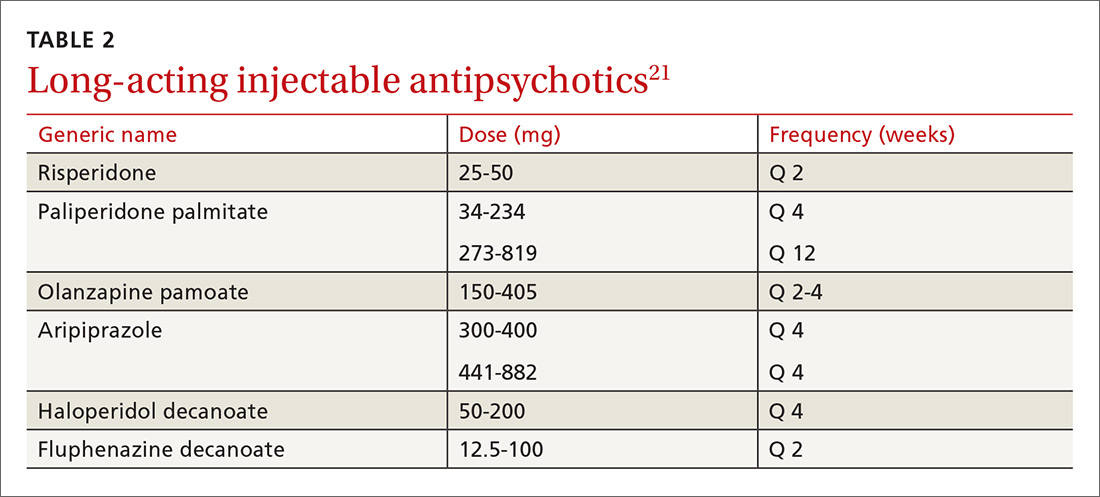

As with all chronic illnesses, success in managing schizophrenia requires patient adherence to the medication regimen. Discontinuation of antipsychotics is a common problem in schizophrenia, resulting in relapse. Long-acting injectable agents (LAIs) were developed to address this problem (TABLE 2).21 Although LAIs are typically used to ensure adherence during maintenance treatment, recent research has suggested they may also be effective for patients with early-phase or first-episode disease.22

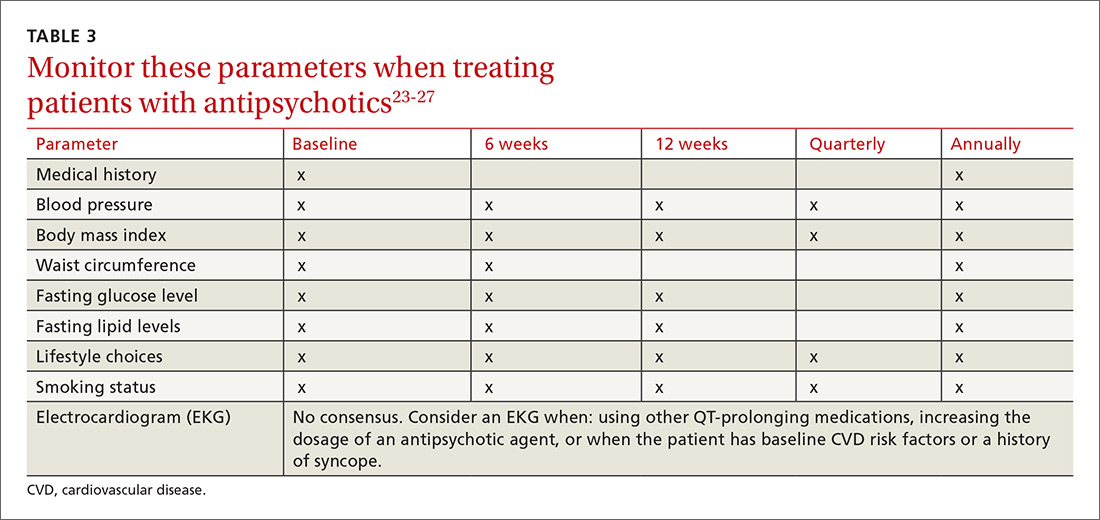

What to watch for. Patients on SGAs may develop metabolic abnormalities, and ongoing monitoring of relevant parameters is key (TABLE 323-27). More frequent monitoring may be necessary in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Continue antipsychotics for at least 6 months to prevent relapse.12 Also keep in mind the “Choosing Wisely” recommendation from the American Psychiatric Association of not prescribing 2 or more antipsychotics concurrently.28

Adjunctive treatment should also be offered

In addition to receiving medication, patients with schizophrenia should be offered adjunctive therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy, family intervention, and social skills training.10-12 Among patients with schizophrenia, the incidences of anxiety disorder, panic symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder are higher than in the general population.29 To address these conditions, medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anxiolytics can be used simultaneously with antipsychotic agents.

CLINICAL COURSE AND PROGNOSIS CAN VARY

Schizophrenia can have a variable clinical course that includes remissions and exacerbations, or it can follow a more persistently chronic course.

Mortality for patients with schizophrenia is 2 to 3 times higher than that of the general population.30 Most deaths are due to an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, cancer, stroke, and other thromboembolic events.30

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among individuals with schizophrenia is 20% to 40%,31 and approximately 5% complete suicide.32 Risk factors include command hallucinations, a history of suicide attempts, intoxication with substances, anxiety, and physical pain.32 Clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and may be considered for patients who are at high risk for suicide.32

Therapeutic response varies among patients with schizophrenia, with one-third remaining symptomatic despite adequate treatment regimens.4

CARE MANAGERS CAN HELP ADDRESS BARRIERS TO CARE

A review of the literature suggests that up to one-third of individuals with serious mental illnesses who have had some contact with the mental health system disengage from care.12 Poor engagement may lead to worse clinical outcomes, with symptom relapse and re-hospitalizations. Disengagement from treatment may indicate a patient’s belief that treatment is not necessary, is not meeting his or her needs, or is not being provided in a collaborative manner.

Although shared decision-making is difficult with patients who have schizophrenia, emerging evidence suggests that this approach coupled with patient-centered care will improve engagement with mental health treatment.12 Models of integrated care are being developed and have shown promise in ensuring access to behavioral health for these patients.34

CASE

The primary care physician talked with Mr. R and his mother about the diagnosis of schizophrenia. He screened for suicide risk, and the patient denied having suicidal thoughts. Both the patient and his mother agreed to his starting medication.

Blood and urine samples were collected for a CBC and ESR, as well as to evaluate renal function, electrolytes, glucose, TSH, vitamin B12, folic acid, ANAs, and HIV antibodies. A serum FTA-ABS test was done, as was a urine culture and sensitivity test and a toxicology screen. Because of the patient’s obesity, the physician decided to prescribe a weight-neutral SGA, aripiprazole 10 mg/d. The physician spoke with the clinic’s care coordinator to schedule an appointment with the psychiatry intake department and to follow up on the phone with the patient and his mother. He also scheduled a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks later.

At the follow-up visit, the patient showed no improvement. His blood and urine test results revealed no metabolic abnormalities or infectious or inflammatory illnesses. His urine toxicology result showed no illicit substances. The physician increased the dosage of aripiprazole to 15 mg/d and asked the patient to return in 2 weeks.

At the next follow-up visit, the patient was more verbal and said he was not hearing voices. His mother also acknowledged an improvement. He had already been scheduled for a psychiatry intake appointment, and he and his mother were reminded about this. Mr. R was also asked to make a follow-up primary care appointment for one month from the current visit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (Fnu) Rajesh, MD, MetroHealth Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; frajesh@metrohealth.org.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67-76.

3. Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term and clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:716-728.

4. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635-645.

5. Holder SD, Wayhs A. Schizophrenia. Am Fam Phys. 2014;90:775-82.

6. Lakhan SE, Vieira KF. Schizophrenia pathophysiology: are we any closer to a complete model? Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009;8:12.

7. Crismon L, Argo TR, Buckley PF. Schizophrenia. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 9th ed. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014:1019-1046.

8. Viron M, Baggett T, Hill M, et al. Schizophrenia for primary care providers: how to contribute to the care of a vulnerable patient population. Am J Med. 2012;125:223-230.

9. Freudenreich O, Charles Schulz SC, Goff DC. Initial medical work-up of first-episode psychosis: a conceptual review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3:10-18.

10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Prevention and management. 2014. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG178. Accessed January 3, 2017.

11. Guo X, Zhai J, Liu Z, et al. Effect of antipsychotic medication alone vs combined with psychosocial intervention on outcomes of early-stage schizophrenia: a randomized 1-year study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:895-904.

12. Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2009;36:94-103.

13. Viron MJ, Stern TA. The impact of serious mental illness on health and healthcare. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:458-465.

14. Jones PB, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on quality of life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1079-1087.

15. Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S, et al. Antipsychotics in adults with schizophrenia: comparative effectiveness of first-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:498-511.

16. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209-1223.

17. Tandon R. Antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: an overview. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(suppl 1):4-8.

18. Salimi K, Jarskog LF, Lieberman JA. Antipsychotic drugs for first-episode schizophrenia: a comparative review. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:837-855.

19. Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatments of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:892-899.

20. Moore TA, Buchanan RW, Buckley PF, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1751-1762.

21. Bera R. Patient outcomes within schizophrenia treatment: a look at the role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(suppl 2):30-33.

22. Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1-24.

23. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:225-233.

24. De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:99-105.

25. Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:306-318.

26. Lieberman JA, Merrill D, Parameswaran S. APA guidance on the use of antipsychotic drugs and cardiac sudden death.

27. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1334-1349.

28. American Psychiatric Association. Five things physicians and patients should question. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-psychiatric-association/. Accessed February 28, 2017.

29. Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:383-402.

30. Lwin AM, Symeon C, Jan F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2011;72:628-630.

31. Pompili M, Amador XF, Girardi P, et al. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: learning from the past to change the future. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:10.

32. Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 suppl):81-90.

33. Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:151-159.

34. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: Evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. Available at: https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolv ing-Models-of-BHI.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2018.

THE CASE

Steven R,* a 21-year-old man, visited the clinic accompanied by his mother. He did not speak much, and his mother provided his history. Over the previous 2 months, she had overheard him whispering in an agitated voice, even though no one else was nearby. And, lately, he refused to answer or make calls on his cell phone, claiming that if he did it would activate a deadly chip that had been implanted in his brain by evil aliens. He also stopped attending classes at the community college. He occasionally had a few beers with his friends, but he had never been known to abuse alcohol or use other recreational drugs.

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

CHARACTERISTICS AND SCOPE OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness in which the individual loses contact with reality and often experiences hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorders. Criteria for schizophrenia described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) include signs and symptoms of at least 6 months’ duration, as well as at least one month of active-phase positive and negative symptoms.1

Delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior are examples of positive symptoms. Negative symptoms include a decrease in the range and intensity of expressed emotions (ie, affective flattening) and a diminished initiation of goal-directed activities (ie, avolition).

Approximately 7 in 1000 people will develop the disorder in their lifetime.2 Schizophrenia is considered a “serious mental illness” because of its chronic course and often poor long-term social and vocational outcomes.3,4 Symptom onset is generally between late adolescence and the mid-30s.5

Getting closer to understanding its origin

Both genetic susceptibility and environmental factors influence the incidence of schizophrenia.4 Newer models of the disease have identified genes (ZDHHC8 and DTNBP1) whose mutations may increase the risk of schizophrenia.6 Physiologic insults during fetal life—hypoxia, maternal infection, maternal stress, and maternal malnutrition—account for a small portion of schizophrenia cases.6

Abnormalities in neurotransmission are the basis for theories on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Most of these theories center on either an excess or a deficiency of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. Other theories implicate aspartate, glycine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid as part of the neurochemical imbalance of schizophrenia.7

ESTABLISHING A DIAGNOSIS

Although psychotic symptoms may be a prominent part of schizophrenia, not all psychoses indicate a primary psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia. Broadly, psychoses can be categorized as primary or secondary.

Primary psychoses include schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and mood disorders (major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder) with psychotic features.1 Difficulty in distinguishing between these entities can necessitate referral to a psychiatrist.

Secondary psychoses arise from a precursor such as delirium, dementia, medical illness, or adverse effects of medications or illicit substances. Medical illnesses that cause psychotic symptoms include: 5,8

- seizures (especially temporal lobe epilepsy),

- cerebrovascular accidents,

- intracranial space-occupying lesions,

- neuropsychiatric disorders (eg, Wilson’s or Parkinson’s disease),

- endocrine disorders (eg, thyroid or adrenal disease),

- autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, Hashimoto encephalopathy),

- deficiencies of vitamins A, B1, B12, or niacin,

- infections (eg, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], encephalitis, parasites, and prion disease),

- narcolepsy, and

- metabolic disease (eg, acute intermittent porphyria, Tay-Sach’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease).

Several recreational drugs can cause psychotic symptoms: cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids, inhalants, opioids, and hallucinogens. Psychotic symptoms can also appear during withdrawal from alcohol (delirium tremens) and from sedative hypnotics such as benzodiazepines. Prescribed medications such as anticholinergics, corticosteroids, dopaminergic agents (L-dopa), stimulants (amphetamines), and interferons can also induce psychotic symptoms.

First rule out causes of secondary psychosis

Rule out causes of secondary psychosis by conducting a detailed history and physical examination and ordering appropriate lab tests and imaging studies. If the patient’s psychosis is of recent onset, make sure the laboratory work-up includes

Consider cranial computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging if there are focal neurologic deficits or if the patient’s presentation is atypical (eg, new onset psychosis in old age).9 Clinical presentation may also indicate a need for electroencephalography, ceruloplasmin measurement, a dexamethasone suppression test, a corticotropin stimulation test, 24-hour urine porphyrin and copper assays, chest radiography, or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.9

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN TREATMENT DECISIONS

Although primary care physicians may encounter individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis, it’s more likely that patients presenting with signs and symptoms of the disorder have been experiencing them for some time and have received no psychiatric care. In both instances, schizophrenia is best managed in conjunction with a psychiatrist until symptoms are stabilized.5 Psychosis does not always require hospitalization. But urgent psychiatry referral is recommended, if possible. Consider admission to a psychiatric inpatient unit for anyone who poses a danger to self or others.8,10

Treatment for schizophrenia is most effective with an interprofessional and collaborative approach that includes medication, psychological treatment, social supports, and primary care clinical management.11,12 The last aspect takes on particular importance given that people with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, have a higher incidence of medical illness, particularly cardiovascular disease.13

Medications (TABLE 15,8) are grouped into first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics (SGAs), with the 2 classes being equally effective.14-16 Quality of life is also similar at one year for patients treated with either drug class.14

Adverse effects can differ. The main difference between these medications is their adverse effect profiles. FGAs cause extrapyramidal symptoms (dystonia, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia) more often than SGAs. Among the SGAs, olanzapine, asenapine, paliperidone, clozapine, and quetiapine cause significant weight gain, glucose dysregulation, and lipid abnormalities.5,8,12,17 Clozapine is associated with agranulocytosis, as well. Risperidone causes mild to moderate weight gain.5,8,12,17 Aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone are considered weight neutral and cause no significant glucose dysregulation or lipid abnormalities.5,8,12,17 All antipsychotics can cause QT prolongation and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.5,8,12,17

Keys to successful treatment. Antipsychotics are most effective in treating positive symptoms of schizophrenia and show limited, if any, effect on negative or cognitive symptoms.18,19 Give patients an adequate trial of therapy (at least 4 weeks at a therapeutic dose) before discontinuing the drug or offering a different medication.20 All patients who report symptom relief while receiving antipsychotics should receive maintenance therapy.12

As with all chronic illnesses, success in managing schizophrenia requires patient adherence to the medication regimen. Discontinuation of antipsychotics is a common problem in schizophrenia, resulting in relapse. Long-acting injectable agents (LAIs) were developed to address this problem (TABLE 2).21 Although LAIs are typically used to ensure adherence during maintenance treatment, recent research has suggested they may also be effective for patients with early-phase or first-episode disease.22

What to watch for. Patients on SGAs may develop metabolic abnormalities, and ongoing monitoring of relevant parameters is key (TABLE 323-27). More frequent monitoring may be necessary in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Continue antipsychotics for at least 6 months to prevent relapse.12 Also keep in mind the “Choosing Wisely” recommendation from the American Psychiatric Association of not prescribing 2 or more antipsychotics concurrently.28

Adjunctive treatment should also be offered

In addition to receiving medication, patients with schizophrenia should be offered adjunctive therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy, family intervention, and social skills training.10-12 Among patients with schizophrenia, the incidences of anxiety disorder, panic symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder are higher than in the general population.29 To address these conditions, medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anxiolytics can be used simultaneously with antipsychotic agents.

CLINICAL COURSE AND PROGNOSIS CAN VARY

Schizophrenia can have a variable clinical course that includes remissions and exacerbations, or it can follow a more persistently chronic course.

Mortality for patients with schizophrenia is 2 to 3 times higher than that of the general population.30 Most deaths are due to an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, cancer, stroke, and other thromboembolic events.30

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among individuals with schizophrenia is 20% to 40%,31 and approximately 5% complete suicide.32 Risk factors include command hallucinations, a history of suicide attempts, intoxication with substances, anxiety, and physical pain.32 Clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and may be considered for patients who are at high risk for suicide.32

Therapeutic response varies among patients with schizophrenia, with one-third remaining symptomatic despite adequate treatment regimens.4

CARE MANAGERS CAN HELP ADDRESS BARRIERS TO CARE

A review of the literature suggests that up to one-third of individuals with serious mental illnesses who have had some contact with the mental health system disengage from care.12 Poor engagement may lead to worse clinical outcomes, with symptom relapse and re-hospitalizations. Disengagement from treatment may indicate a patient’s belief that treatment is not necessary, is not meeting his or her needs, or is not being provided in a collaborative manner.

Although shared decision-making is difficult with patients who have schizophrenia, emerging evidence suggests that this approach coupled with patient-centered care will improve engagement with mental health treatment.12 Models of integrated care are being developed and have shown promise in ensuring access to behavioral health for these patients.34

CASE

The primary care physician talked with Mr. R and his mother about the diagnosis of schizophrenia. He screened for suicide risk, and the patient denied having suicidal thoughts. Both the patient and his mother agreed to his starting medication.

Blood and urine samples were collected for a CBC and ESR, as well as to evaluate renal function, electrolytes, glucose, TSH, vitamin B12, folic acid, ANAs, and HIV antibodies. A serum FTA-ABS test was done, as was a urine culture and sensitivity test and a toxicology screen. Because of the patient’s obesity, the physician decided to prescribe a weight-neutral SGA, aripiprazole 10 mg/d. The physician spoke with the clinic’s care coordinator to schedule an appointment with the psychiatry intake department and to follow up on the phone with the patient and his mother. He also scheduled a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks later.

At the follow-up visit, the patient showed no improvement. His blood and urine test results revealed no metabolic abnormalities or infectious or inflammatory illnesses. His urine toxicology result showed no illicit substances. The physician increased the dosage of aripiprazole to 15 mg/d and asked the patient to return in 2 weeks.

At the next follow-up visit, the patient was more verbal and said he was not hearing voices. His mother also acknowledged an improvement. He had already been scheduled for a psychiatry intake appointment, and he and his mother were reminded about this. Mr. R was also asked to make a follow-up primary care appointment for one month from the current visit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (Fnu) Rajesh, MD, MetroHealth Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; frajesh@metrohealth.org.

THE CASE

Steven R,* a 21-year-old man, visited the clinic accompanied by his mother. He did not speak much, and his mother provided his history. Over the previous 2 months, she had overheard him whispering in an agitated voice, even though no one else was nearby. And, lately, he refused to answer or make calls on his cell phone, claiming that if he did it would activate a deadly chip that had been implanted in his brain by evil aliens. He also stopped attending classes at the community college. He occasionally had a few beers with his friends, but he had never been known to abuse alcohol or use other recreational drugs.

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

CHARACTERISTICS AND SCOPE OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness in which the individual loses contact with reality and often experiences hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorders. Criteria for schizophrenia described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) include signs and symptoms of at least 6 months’ duration, as well as at least one month of active-phase positive and negative symptoms.1

Delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior are examples of positive symptoms. Negative symptoms include a decrease in the range and intensity of expressed emotions (ie, affective flattening) and a diminished initiation of goal-directed activities (ie, avolition).

Approximately 7 in 1000 people will develop the disorder in their lifetime.2 Schizophrenia is considered a “serious mental illness” because of its chronic course and often poor long-term social and vocational outcomes.3,4 Symptom onset is generally between late adolescence and the mid-30s.5

Getting closer to understanding its origin

Both genetic susceptibility and environmental factors influence the incidence of schizophrenia.4 Newer models of the disease have identified genes (ZDHHC8 and DTNBP1) whose mutations may increase the risk of schizophrenia.6 Physiologic insults during fetal life—hypoxia, maternal infection, maternal stress, and maternal malnutrition—account for a small portion of schizophrenia cases.6

Abnormalities in neurotransmission are the basis for theories on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Most of these theories center on either an excess or a deficiency of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. Other theories implicate aspartate, glycine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid as part of the neurochemical imbalance of schizophrenia.7

ESTABLISHING A DIAGNOSIS

Although psychotic symptoms may be a prominent part of schizophrenia, not all psychoses indicate a primary psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia. Broadly, psychoses can be categorized as primary or secondary.

Primary psychoses include schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and mood disorders (major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder) with psychotic features.1 Difficulty in distinguishing between these entities can necessitate referral to a psychiatrist.

Secondary psychoses arise from a precursor such as delirium, dementia, medical illness, or adverse effects of medications or illicit substances. Medical illnesses that cause psychotic symptoms include: 5,8

- seizures (especially temporal lobe epilepsy),

- cerebrovascular accidents,

- intracranial space-occupying lesions,

- neuropsychiatric disorders (eg, Wilson’s or Parkinson’s disease),

- endocrine disorders (eg, thyroid or adrenal disease),

- autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, Hashimoto encephalopathy),

- deficiencies of vitamins A, B1, B12, or niacin,

- infections (eg, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], encephalitis, parasites, and prion disease),

- narcolepsy, and

- metabolic disease (eg, acute intermittent porphyria, Tay-Sach’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease).

Several recreational drugs can cause psychotic symptoms: cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids, inhalants, opioids, and hallucinogens. Psychotic symptoms can also appear during withdrawal from alcohol (delirium tremens) and from sedative hypnotics such as benzodiazepines. Prescribed medications such as anticholinergics, corticosteroids, dopaminergic agents (L-dopa), stimulants (amphetamines), and interferons can also induce psychotic symptoms.

First rule out causes of secondary psychosis

Rule out causes of secondary psychosis by conducting a detailed history and physical examination and ordering appropriate lab tests and imaging studies. If the patient’s psychosis is of recent onset, make sure the laboratory work-up includes

Consider cranial computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging if there are focal neurologic deficits or if the patient’s presentation is atypical (eg, new onset psychosis in old age).9 Clinical presentation may also indicate a need for electroencephalography, ceruloplasmin measurement, a dexamethasone suppression test, a corticotropin stimulation test, 24-hour urine porphyrin and copper assays, chest radiography, or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.9

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN TREATMENT DECISIONS

Although primary care physicians may encounter individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis, it’s more likely that patients presenting with signs and symptoms of the disorder have been experiencing them for some time and have received no psychiatric care. In both instances, schizophrenia is best managed in conjunction with a psychiatrist until symptoms are stabilized.5 Psychosis does not always require hospitalization. But urgent psychiatry referral is recommended, if possible. Consider admission to a psychiatric inpatient unit for anyone who poses a danger to self or others.8,10

Treatment for schizophrenia is most effective with an interprofessional and collaborative approach that includes medication, psychological treatment, social supports, and primary care clinical management.11,12 The last aspect takes on particular importance given that people with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, have a higher incidence of medical illness, particularly cardiovascular disease.13

Medications (TABLE 15,8) are grouped into first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics (SGAs), with the 2 classes being equally effective.14-16 Quality of life is also similar at one year for patients treated with either drug class.14