User login

Dripping, dabbing, and bongs: Can’t tell the players without a scorecard

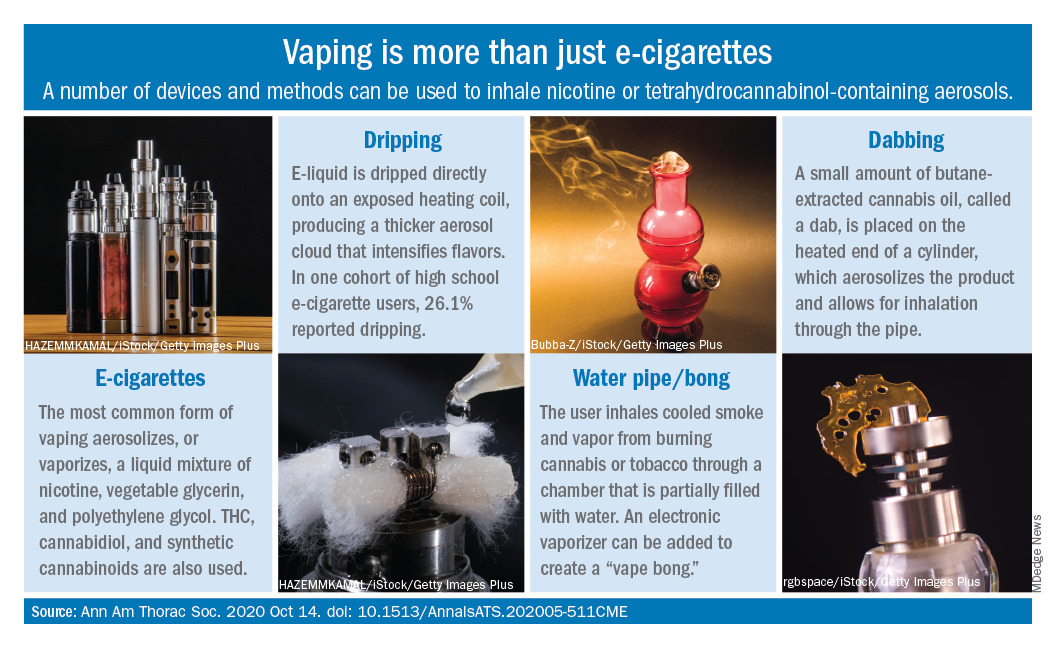

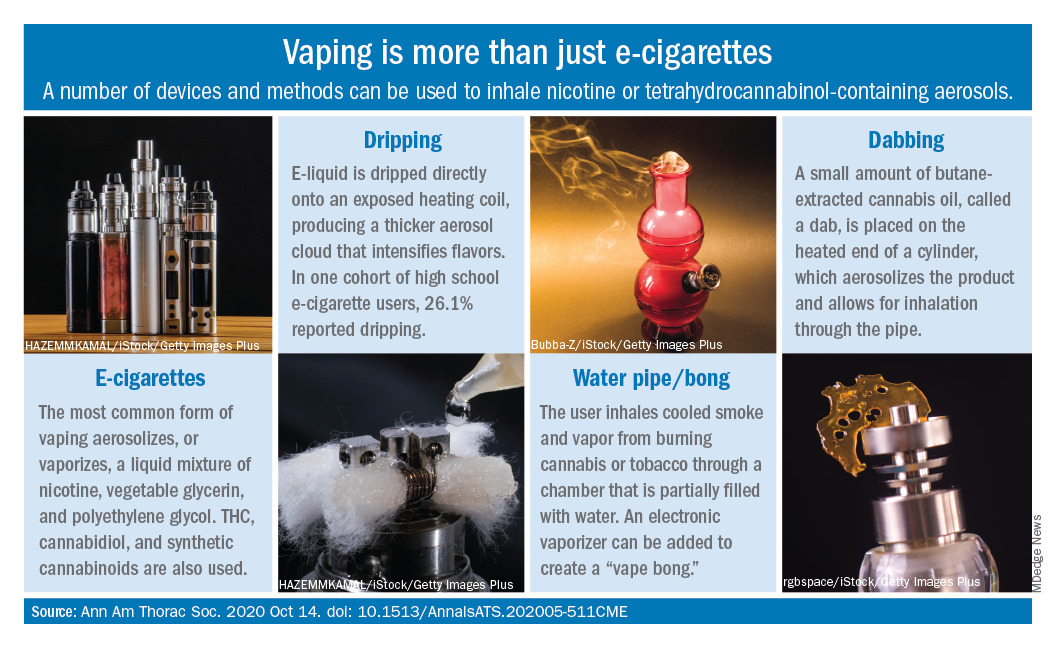

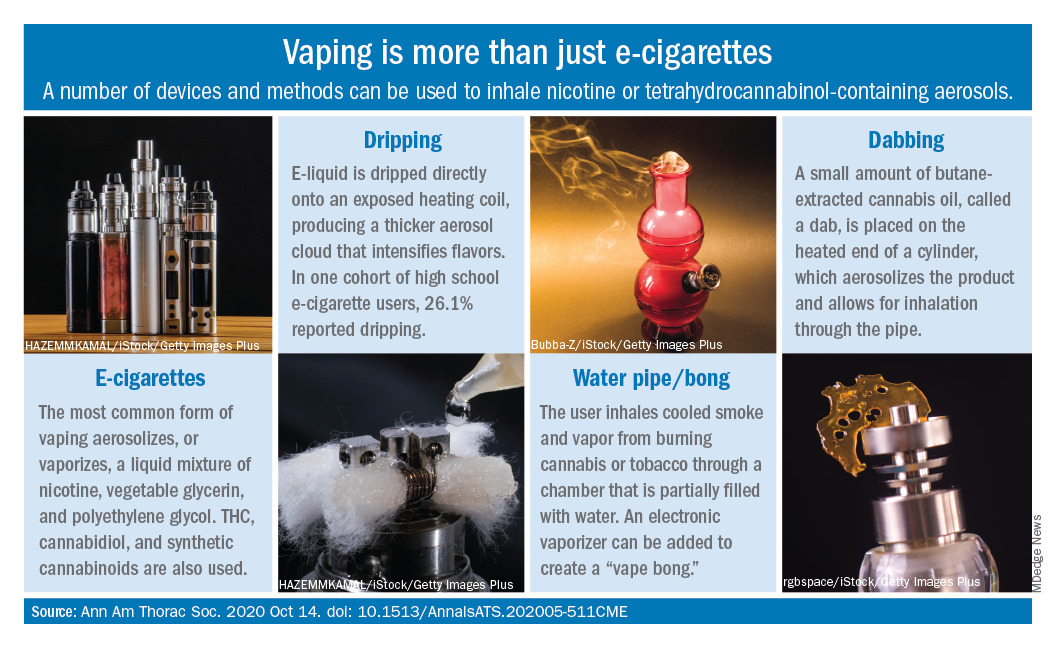

E-cigarettes may be synonymous with vaping to most physicians, but there are other ways for patients to inhale nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol-containing aerosols, according to investigators at the Cleveland Clinic.

Humberto Choi, MD, and associates wrote in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

These “alternate aerosol inhalation methods” have been poorly described thus far, so little is known about their scope of use and potential health impact, they noted.

Dripping involves an e-cigarette modified to expose the heating coil. The e-cigarette liquid is dripped directly onto the hot coil, which produces immediate aerosolization and results in a thicker cloud.

Dripping “may expose users to higher levels of nicotine compared to e-cigarette inhalation” and lead to “increased release of volatile aldehydes as a result of the higher heating potential of direct atomizer exposure,” the investigators suggested.

Water pipes, or bongs, produce both smoke and vapor, although an electronic vaporizer can be attached to create a “vape bong.” About 21% of daily cannabis users report using a bong, but tobacco inhalation is less common. Cases of severe pulmonary infections have been associated with bong use, along with a couple of tuberculosis clusters, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Dabbing uses butane-extracted, concentrated cannabis oil inhaled through a modified water pipe or bong or a smaller device called a “dab pen.” A small amount, or “dab,” of the product is placed on the “nail,” which replaces the bowl of the water pipe, heated with a blowtorch, and inhaled through the pipe, the researchers explained.

The prevalence of dabbing is unknown, but “the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of high school seniors shows that 11.9% of students have used a marijuana vaporizer at some point in their life,” they said.

Besides the fire risks involved in creating the material needed for dabbing – use of heating plates, ovens, and devices for removing butane vapors – inhalation of residual butane vapors could lead to vomiting, cardiac arrhythmias, acute encephalopathy, and respiratory depression, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Nicotine dependence is also a concern, as is the possibility of withdrawal symptoms. “Patients presenting with prolonged and severe vomiting, psychotic symptoms, or other acute neuropsychiatric symptoms should raise the suspicion of [tetrahydrocannabinol]-containing products especially synthetic cannabinoids,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Choi H et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Oct 14. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-511CME.

E-cigarettes may be synonymous with vaping to most physicians, but there are other ways for patients to inhale nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol-containing aerosols, according to investigators at the Cleveland Clinic.

Humberto Choi, MD, and associates wrote in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

These “alternate aerosol inhalation methods” have been poorly described thus far, so little is known about their scope of use and potential health impact, they noted.

Dripping involves an e-cigarette modified to expose the heating coil. The e-cigarette liquid is dripped directly onto the hot coil, which produces immediate aerosolization and results in a thicker cloud.

Dripping “may expose users to higher levels of nicotine compared to e-cigarette inhalation” and lead to “increased release of volatile aldehydes as a result of the higher heating potential of direct atomizer exposure,” the investigators suggested.

Water pipes, or bongs, produce both smoke and vapor, although an electronic vaporizer can be attached to create a “vape bong.” About 21% of daily cannabis users report using a bong, but tobacco inhalation is less common. Cases of severe pulmonary infections have been associated with bong use, along with a couple of tuberculosis clusters, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Dabbing uses butane-extracted, concentrated cannabis oil inhaled through a modified water pipe or bong or a smaller device called a “dab pen.” A small amount, or “dab,” of the product is placed on the “nail,” which replaces the bowl of the water pipe, heated with a blowtorch, and inhaled through the pipe, the researchers explained.

The prevalence of dabbing is unknown, but “the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of high school seniors shows that 11.9% of students have used a marijuana vaporizer at some point in their life,” they said.

Besides the fire risks involved in creating the material needed for dabbing – use of heating plates, ovens, and devices for removing butane vapors – inhalation of residual butane vapors could lead to vomiting, cardiac arrhythmias, acute encephalopathy, and respiratory depression, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Nicotine dependence is also a concern, as is the possibility of withdrawal symptoms. “Patients presenting with prolonged and severe vomiting, psychotic symptoms, or other acute neuropsychiatric symptoms should raise the suspicion of [tetrahydrocannabinol]-containing products especially synthetic cannabinoids,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Choi H et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Oct 14. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-511CME.

E-cigarettes may be synonymous with vaping to most physicians, but there are other ways for patients to inhale nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol-containing aerosols, according to investigators at the Cleveland Clinic.

Humberto Choi, MD, and associates wrote in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

These “alternate aerosol inhalation methods” have been poorly described thus far, so little is known about their scope of use and potential health impact, they noted.

Dripping involves an e-cigarette modified to expose the heating coil. The e-cigarette liquid is dripped directly onto the hot coil, which produces immediate aerosolization and results in a thicker cloud.

Dripping “may expose users to higher levels of nicotine compared to e-cigarette inhalation” and lead to “increased release of volatile aldehydes as a result of the higher heating potential of direct atomizer exposure,” the investigators suggested.

Water pipes, or bongs, produce both smoke and vapor, although an electronic vaporizer can be attached to create a “vape bong.” About 21% of daily cannabis users report using a bong, but tobacco inhalation is less common. Cases of severe pulmonary infections have been associated with bong use, along with a couple of tuberculosis clusters, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Dabbing uses butane-extracted, concentrated cannabis oil inhaled through a modified water pipe or bong or a smaller device called a “dab pen.” A small amount, or “dab,” of the product is placed on the “nail,” which replaces the bowl of the water pipe, heated with a blowtorch, and inhaled through the pipe, the researchers explained.

The prevalence of dabbing is unknown, but “the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of high school seniors shows that 11.9% of students have used a marijuana vaporizer at some point in their life,” they said.

Besides the fire risks involved in creating the material needed for dabbing – use of heating plates, ovens, and devices for removing butane vapors – inhalation of residual butane vapors could lead to vomiting, cardiac arrhythmias, acute encephalopathy, and respiratory depression, Dr. Choi and associates said.

Nicotine dependence is also a concern, as is the possibility of withdrawal symptoms. “Patients presenting with prolonged and severe vomiting, psychotic symptoms, or other acute neuropsychiatric symptoms should raise the suspicion of [tetrahydrocannabinol]-containing products especially synthetic cannabinoids,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Choi H et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Oct 14. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-511CME.

FROM ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY

Triple combination therapy for cystic fibrosis linked to plunging hospitalizations

.

The triple combination therapy elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor was associated with a near elimination of hospital stays in one hospital in Oregon, according to a new report. The hospital savings still weren’t nearly enough to pay for the cost of therapy, but the study underscores what many institutions have observed and adds a new layer to the view of quality of life improvements that the new therapy brings.

“After we started prescribing it, we noticed pretty quickly that hospitalizations appeared to be declining after patients started triple combination therapy, and we were hearing [similar reports] from other centers as well. We wanted to quantify this,” Eric C. Walter, MD, a pulmonologist at the Kaiser Permanente Cystic Fibrosis Clinic in Portland, Ore., said during a presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“We’re seeing that across the board in real practice, the number of cystic fibrosis patients that have to be hospitalized since starting this triple combination has gone down,” Robert Giusti, MD, said in an interview. “When they’ve had pulmonary exacerbations in the past, it was frequently because they failed outpatient antibiotics, but I think with triple combination therapy, if they do get sick, the likelihood is they will respond to oral antibiotics, so they may not need that prolonged IV course in the hospital.” Dr. Giusti is clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center. He was not involved in the study.

The therapy gained Food and Drug Administration approval in 2019 for the treatment of individuals with CF who are aged 12 years and older, and who have at least one copy of the F508del mutation. Its cost is about $317,000 per year within the Kaiser Permanente system, according to Dr. Walter. His group compared hospitalization days for CF-related diagnoses from Jan. 1 through Aug. 31, 2020, before and after initiation of triple combination therapy.

Of 47 eligible patients, 32 initiated therapy during the study period; 38% had severe lung disease, defined by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) value less than 40%. In 2020, before initiation of therapy, there were an average of 27 hospital days per month, all among patients with severe lung disease.

Among the therapy group, there were no hospitalizations after initiation of therapy through Aug. 31. Dr. Walter noted that the first hospitalization of a patient on triple combination therapy didn’t occur until early October.

At an average daily cost of $6,700, the researchers calculated that triple combination therapy saved about $189,000 per month in this group of patients. Comparing numbers to previous years, in which some patients with FEV1 greater than 40% were hospitalized, the researchers calculated that the therapy saved about $151,000 per month among individuals with severe lung disease: Patients with severe lung disease contributed about 80% to total hospital costs.

The drug itself for the whole group cost $845,000, dwarfing the $189,000 savings overall. But among patients with severe disease, hospitalization savings were about $151,000 per month, while the drug cost in this group was $316,800 per month.

Cost savings are important, but the improvement in quality of life for a patient – avoiding hospitalization, fewer impacts on work and education – should not be overlooked, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who moderated the session. “Some of these aren’t things people typically quantify and assign a price tag to,” Dr. Perkins said in an interview.

A big limitation of the work is that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced hospitalizations. “We did have patients that called in, told us they were sick, that they needed to be treated for an exacerbation but didn’t want to go to the hospital,” said Dr. Walter. To help adjust for this, Dr. Walter’s team plans to compare intravenous antibiotic exposure before and after triple combination therapy, reasoning that it could help clarify the pandemic’s impact on hospitalizations.

Dr. Walter, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter E et al. NACFC 2020. Abstract 795.

.

The triple combination therapy elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor was associated with a near elimination of hospital stays in one hospital in Oregon, according to a new report. The hospital savings still weren’t nearly enough to pay for the cost of therapy, but the study underscores what many institutions have observed and adds a new layer to the view of quality of life improvements that the new therapy brings.

“After we started prescribing it, we noticed pretty quickly that hospitalizations appeared to be declining after patients started triple combination therapy, and we were hearing [similar reports] from other centers as well. We wanted to quantify this,” Eric C. Walter, MD, a pulmonologist at the Kaiser Permanente Cystic Fibrosis Clinic in Portland, Ore., said during a presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“We’re seeing that across the board in real practice, the number of cystic fibrosis patients that have to be hospitalized since starting this triple combination has gone down,” Robert Giusti, MD, said in an interview. “When they’ve had pulmonary exacerbations in the past, it was frequently because they failed outpatient antibiotics, but I think with triple combination therapy, if they do get sick, the likelihood is they will respond to oral antibiotics, so they may not need that prolonged IV course in the hospital.” Dr. Giusti is clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center. He was not involved in the study.

The therapy gained Food and Drug Administration approval in 2019 for the treatment of individuals with CF who are aged 12 years and older, and who have at least one copy of the F508del mutation. Its cost is about $317,000 per year within the Kaiser Permanente system, according to Dr. Walter. His group compared hospitalization days for CF-related diagnoses from Jan. 1 through Aug. 31, 2020, before and after initiation of triple combination therapy.

Of 47 eligible patients, 32 initiated therapy during the study period; 38% had severe lung disease, defined by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) value less than 40%. In 2020, before initiation of therapy, there were an average of 27 hospital days per month, all among patients with severe lung disease.

Among the therapy group, there were no hospitalizations after initiation of therapy through Aug. 31. Dr. Walter noted that the first hospitalization of a patient on triple combination therapy didn’t occur until early October.

At an average daily cost of $6,700, the researchers calculated that triple combination therapy saved about $189,000 per month in this group of patients. Comparing numbers to previous years, in which some patients with FEV1 greater than 40% were hospitalized, the researchers calculated that the therapy saved about $151,000 per month among individuals with severe lung disease: Patients with severe lung disease contributed about 80% to total hospital costs.

The drug itself for the whole group cost $845,000, dwarfing the $189,000 savings overall. But among patients with severe disease, hospitalization savings were about $151,000 per month, while the drug cost in this group was $316,800 per month.

Cost savings are important, but the improvement in quality of life for a patient – avoiding hospitalization, fewer impacts on work and education – should not be overlooked, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who moderated the session. “Some of these aren’t things people typically quantify and assign a price tag to,” Dr. Perkins said in an interview.

A big limitation of the work is that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced hospitalizations. “We did have patients that called in, told us they were sick, that they needed to be treated for an exacerbation but didn’t want to go to the hospital,” said Dr. Walter. To help adjust for this, Dr. Walter’s team plans to compare intravenous antibiotic exposure before and after triple combination therapy, reasoning that it could help clarify the pandemic’s impact on hospitalizations.

Dr. Walter, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter E et al. NACFC 2020. Abstract 795.

.

The triple combination therapy elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor was associated with a near elimination of hospital stays in one hospital in Oregon, according to a new report. The hospital savings still weren’t nearly enough to pay for the cost of therapy, but the study underscores what many institutions have observed and adds a new layer to the view of quality of life improvements that the new therapy brings.

“After we started prescribing it, we noticed pretty quickly that hospitalizations appeared to be declining after patients started triple combination therapy, and we were hearing [similar reports] from other centers as well. We wanted to quantify this,” Eric C. Walter, MD, a pulmonologist at the Kaiser Permanente Cystic Fibrosis Clinic in Portland, Ore., said during a presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“We’re seeing that across the board in real practice, the number of cystic fibrosis patients that have to be hospitalized since starting this triple combination has gone down,” Robert Giusti, MD, said in an interview. “When they’ve had pulmonary exacerbations in the past, it was frequently because they failed outpatient antibiotics, but I think with triple combination therapy, if they do get sick, the likelihood is they will respond to oral antibiotics, so they may not need that prolonged IV course in the hospital.” Dr. Giusti is clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center. He was not involved in the study.

The therapy gained Food and Drug Administration approval in 2019 for the treatment of individuals with CF who are aged 12 years and older, and who have at least one copy of the F508del mutation. Its cost is about $317,000 per year within the Kaiser Permanente system, according to Dr. Walter. His group compared hospitalization days for CF-related diagnoses from Jan. 1 through Aug. 31, 2020, before and after initiation of triple combination therapy.

Of 47 eligible patients, 32 initiated therapy during the study period; 38% had severe lung disease, defined by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) value less than 40%. In 2020, before initiation of therapy, there were an average of 27 hospital days per month, all among patients with severe lung disease.

Among the therapy group, there were no hospitalizations after initiation of therapy through Aug. 31. Dr. Walter noted that the first hospitalization of a patient on triple combination therapy didn’t occur until early October.

At an average daily cost of $6,700, the researchers calculated that triple combination therapy saved about $189,000 per month in this group of patients. Comparing numbers to previous years, in which some patients with FEV1 greater than 40% were hospitalized, the researchers calculated that the therapy saved about $151,000 per month among individuals with severe lung disease: Patients with severe lung disease contributed about 80% to total hospital costs.

The drug itself for the whole group cost $845,000, dwarfing the $189,000 savings overall. But among patients with severe disease, hospitalization savings were about $151,000 per month, while the drug cost in this group was $316,800 per month.

Cost savings are important, but the improvement in quality of life for a patient – avoiding hospitalization, fewer impacts on work and education – should not be overlooked, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who moderated the session. “Some of these aren’t things people typically quantify and assign a price tag to,” Dr. Perkins said in an interview.

A big limitation of the work is that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced hospitalizations. “We did have patients that called in, told us they were sick, that they needed to be treated for an exacerbation but didn’t want to go to the hospital,” said Dr. Walter. To help adjust for this, Dr. Walter’s team plans to compare intravenous antibiotic exposure before and after triple combination therapy, reasoning that it could help clarify the pandemic’s impact on hospitalizations.

Dr. Walter, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter E et al. NACFC 2020. Abstract 795.

FROM NACFC 2020

Cystic fibrosis patients’ vulnerability to COVID-19 infection: Preliminary data ease fears

But early results suggest that social distance measures and perhaps the younger average age of individuals with CF have prevented a severe impact on this patient population.

Not all of the news is good. Some research suggests that posttransplant individuals may be at greater risk of severe outcomes. However, researchers warned that the data are too sparse to draw firm conclusions, and ongoing analyses of patient registries and other sources should lend greater insight into the burden of COVID-19 among individuals with CF. Those were some of the conclusions presented at a session of the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

D.B. Sanders, MD, who is a pediatric pulmonologist at Riley Hospital for Children and the Indiana University, both in Indianapolis, presented data from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Patient Registry, which includes patients in the United States. As in other populations, he showed that health care use has gone down among individuals with CF. From April to September 2019, 81% of clinical encounters were in the clinic and 12% in the hospital. Over the same period in 2020, those numbers dropped to 35% and 4%, respectively, with 30% by phone or computer. In-person health care use rebounded somewhat between July 1 and Sept. 16, with 53% of encounters at the clinic, 5% at the hospital, and 28% conducted virtually. There were also dips in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and microbiology testing, from about 90% occurring during health encounters at the end of 2019 to fewer than 10% of encounters by April.

As of Aug. 17, Dr. Sanders reported that 3,048 individuals with CF had been tested for COVID-19, with 174 positive results.

Racial and ethnic disparities in positive test results seen in other populations were also observable among individuals with CF. Several groups made up a higher proportion of COVID-19–positive CF patients than the general CF population, including Hispanics (18% vs. 9%), Blacks (7% vs. 5%), and individuals with FEV1 value less than 40% predicted (14% vs. 8%).

As of Sept. 17, there had been 51 hospitalizations and two deaths in the United States among 212 individuals with CF who tested positive for COVID-19, with increasing numbers that mirror trends in the U.S. population. One death occurred in a patient with advanced lung disease, the other in a post–lung transplant patient. “Thankfully [the numbers are] not higher, but this is being followed very closely,” said Dr. Sanders during his presentation.

One encouraging bit of news was that hospitalizations among individuals with CF have dropped since the start of the pandemic. “I think this shows how good our families are at socially distancing, wearing masks, and now that they not being exposed to viruses, I think we’re seeing the fruits of this with fewer hospitalizations,” said Dr. Sanders. He noted that it’s possible some of the decline could have been to reluctance to go to the hospital, and the introduction of triple combination cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulator therapy has also likely contributed. “We were already seeing fewer hospitalizations even before the pandemic hit,” he said.

At the session, Rebecca Cosgriff, director of data and quality improvement at the Cystic Fibrosis Trust in the United Kingdom, presented an international perspective on COVID-19 cases among individuals with CF. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Cystic Fibrosis Global Registry Harmonization Group recruited country coordinators to collect anonymized data on infections, hospitalizations, and other outcomes. In April, the group published its initial findings from 40 cases in eight countries, which concluded that these cases generally resembled the broader population in clinical course, which assuaged initial fears.

Ms. Cosgriff reported on results from a second round of data collection with a cutoff date of June 19, which expanded to 19 countries and included many from South America and more in Europe. The network encompassed about 85,000 individuals with CF, and tallied 181 cases of COVID-19. A total of 149 cases were nontransplant, and 32 were posttransplant (28 lung only). Fully 15% of the nontransplant group were over age 40 years, compared with 41% in the transplant group. Homozygous F508del mutations were more common in the posttransplant group (59% vs. 36%). However, lung function, as estimated by the best FEV1 measured in the previous year prior to infection, differed between the nontransplant (73%) and posttransplant (80%) COVID-19 patients.

Across all age groups, hospitalizations were more common in patients with best FEV1 percentage predicted values less than 70% (P = .001). Ms. Cosgriff also expressed concern about the posttransplant group. “Across all outcomes that might be indicative of infection severity – hospitalization, ICU admission, new supplementary oxygen, and non-invasive ventilation – the proportion of the posttransplant group was higher across the board,” she said during her presentation.

There were seven deaths. Ms. Cosgriff noted that there were too few deaths to analyze trends, but she presented a slide showing characteristics of deceased patients. “Factors like being post–lung transplant, being male, having less FEV1 than predicted, being over 40, or having CF-related diabetes, all appear pretty frequently amongst the cohort of people who died,” she said.

Overall, the results of these surveys are encouraging, suggesting that early fears that COVID-19 cases could be more severe among individuals with CF may not have been borne out so far. Dr. Sanders noted in his talk that there aren’t enough cases in the U.S. cohort to show links to risk factors with statistical significance. “But thankfully we’re not seeing a host of negative outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Sanders and Ms Cosgriff have no relevant financial disclosures.

But early results suggest that social distance measures and perhaps the younger average age of individuals with CF have prevented a severe impact on this patient population.

Not all of the news is good. Some research suggests that posttransplant individuals may be at greater risk of severe outcomes. However, researchers warned that the data are too sparse to draw firm conclusions, and ongoing analyses of patient registries and other sources should lend greater insight into the burden of COVID-19 among individuals with CF. Those were some of the conclusions presented at a session of the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

D.B. Sanders, MD, who is a pediatric pulmonologist at Riley Hospital for Children and the Indiana University, both in Indianapolis, presented data from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Patient Registry, which includes patients in the United States. As in other populations, he showed that health care use has gone down among individuals with CF. From April to September 2019, 81% of clinical encounters were in the clinic and 12% in the hospital. Over the same period in 2020, those numbers dropped to 35% and 4%, respectively, with 30% by phone or computer. In-person health care use rebounded somewhat between July 1 and Sept. 16, with 53% of encounters at the clinic, 5% at the hospital, and 28% conducted virtually. There were also dips in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and microbiology testing, from about 90% occurring during health encounters at the end of 2019 to fewer than 10% of encounters by April.

As of Aug. 17, Dr. Sanders reported that 3,048 individuals with CF had been tested for COVID-19, with 174 positive results.

Racial and ethnic disparities in positive test results seen in other populations were also observable among individuals with CF. Several groups made up a higher proportion of COVID-19–positive CF patients than the general CF population, including Hispanics (18% vs. 9%), Blacks (7% vs. 5%), and individuals with FEV1 value less than 40% predicted (14% vs. 8%).

As of Sept. 17, there had been 51 hospitalizations and two deaths in the United States among 212 individuals with CF who tested positive for COVID-19, with increasing numbers that mirror trends in the U.S. population. One death occurred in a patient with advanced lung disease, the other in a post–lung transplant patient. “Thankfully [the numbers are] not higher, but this is being followed very closely,” said Dr. Sanders during his presentation.

One encouraging bit of news was that hospitalizations among individuals with CF have dropped since the start of the pandemic. “I think this shows how good our families are at socially distancing, wearing masks, and now that they not being exposed to viruses, I think we’re seeing the fruits of this with fewer hospitalizations,” said Dr. Sanders. He noted that it’s possible some of the decline could have been to reluctance to go to the hospital, and the introduction of triple combination cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulator therapy has also likely contributed. “We were already seeing fewer hospitalizations even before the pandemic hit,” he said.

At the session, Rebecca Cosgriff, director of data and quality improvement at the Cystic Fibrosis Trust in the United Kingdom, presented an international perspective on COVID-19 cases among individuals with CF. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Cystic Fibrosis Global Registry Harmonization Group recruited country coordinators to collect anonymized data on infections, hospitalizations, and other outcomes. In April, the group published its initial findings from 40 cases in eight countries, which concluded that these cases generally resembled the broader population in clinical course, which assuaged initial fears.

Ms. Cosgriff reported on results from a second round of data collection with a cutoff date of June 19, which expanded to 19 countries and included many from South America and more in Europe. The network encompassed about 85,000 individuals with CF, and tallied 181 cases of COVID-19. A total of 149 cases were nontransplant, and 32 were posttransplant (28 lung only). Fully 15% of the nontransplant group were over age 40 years, compared with 41% in the transplant group. Homozygous F508del mutations were more common in the posttransplant group (59% vs. 36%). However, lung function, as estimated by the best FEV1 measured in the previous year prior to infection, differed between the nontransplant (73%) and posttransplant (80%) COVID-19 patients.

Across all age groups, hospitalizations were more common in patients with best FEV1 percentage predicted values less than 70% (P = .001). Ms. Cosgriff also expressed concern about the posttransplant group. “Across all outcomes that might be indicative of infection severity – hospitalization, ICU admission, new supplementary oxygen, and non-invasive ventilation – the proportion of the posttransplant group was higher across the board,” she said during her presentation.

There were seven deaths. Ms. Cosgriff noted that there were too few deaths to analyze trends, but she presented a slide showing characteristics of deceased patients. “Factors like being post–lung transplant, being male, having less FEV1 than predicted, being over 40, or having CF-related diabetes, all appear pretty frequently amongst the cohort of people who died,” she said.

Overall, the results of these surveys are encouraging, suggesting that early fears that COVID-19 cases could be more severe among individuals with CF may not have been borne out so far. Dr. Sanders noted in his talk that there aren’t enough cases in the U.S. cohort to show links to risk factors with statistical significance. “But thankfully we’re not seeing a host of negative outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Sanders and Ms Cosgriff have no relevant financial disclosures.

But early results suggest that social distance measures and perhaps the younger average age of individuals with CF have prevented a severe impact on this patient population.

Not all of the news is good. Some research suggests that posttransplant individuals may be at greater risk of severe outcomes. However, researchers warned that the data are too sparse to draw firm conclusions, and ongoing analyses of patient registries and other sources should lend greater insight into the burden of COVID-19 among individuals with CF. Those were some of the conclusions presented at a session of the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

D.B. Sanders, MD, who is a pediatric pulmonologist at Riley Hospital for Children and the Indiana University, both in Indianapolis, presented data from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Patient Registry, which includes patients in the United States. As in other populations, he showed that health care use has gone down among individuals with CF. From April to September 2019, 81% of clinical encounters were in the clinic and 12% in the hospital. Over the same period in 2020, those numbers dropped to 35% and 4%, respectively, with 30% by phone or computer. In-person health care use rebounded somewhat between July 1 and Sept. 16, with 53% of encounters at the clinic, 5% at the hospital, and 28% conducted virtually. There were also dips in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and microbiology testing, from about 90% occurring during health encounters at the end of 2019 to fewer than 10% of encounters by April.

As of Aug. 17, Dr. Sanders reported that 3,048 individuals with CF had been tested for COVID-19, with 174 positive results.

Racial and ethnic disparities in positive test results seen in other populations were also observable among individuals with CF. Several groups made up a higher proportion of COVID-19–positive CF patients than the general CF population, including Hispanics (18% vs. 9%), Blacks (7% vs. 5%), and individuals with FEV1 value less than 40% predicted (14% vs. 8%).

As of Sept. 17, there had been 51 hospitalizations and two deaths in the United States among 212 individuals with CF who tested positive for COVID-19, with increasing numbers that mirror trends in the U.S. population. One death occurred in a patient with advanced lung disease, the other in a post–lung transplant patient. “Thankfully [the numbers are] not higher, but this is being followed very closely,” said Dr. Sanders during his presentation.

One encouraging bit of news was that hospitalizations among individuals with CF have dropped since the start of the pandemic. “I think this shows how good our families are at socially distancing, wearing masks, and now that they not being exposed to viruses, I think we’re seeing the fruits of this with fewer hospitalizations,” said Dr. Sanders. He noted that it’s possible some of the decline could have been to reluctance to go to the hospital, and the introduction of triple combination cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulator therapy has also likely contributed. “We were already seeing fewer hospitalizations even before the pandemic hit,” he said.

At the session, Rebecca Cosgriff, director of data and quality improvement at the Cystic Fibrosis Trust in the United Kingdom, presented an international perspective on COVID-19 cases among individuals with CF. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Cystic Fibrosis Global Registry Harmonization Group recruited country coordinators to collect anonymized data on infections, hospitalizations, and other outcomes. In April, the group published its initial findings from 40 cases in eight countries, which concluded that these cases generally resembled the broader population in clinical course, which assuaged initial fears.

Ms. Cosgriff reported on results from a second round of data collection with a cutoff date of June 19, which expanded to 19 countries and included many from South America and more in Europe. The network encompassed about 85,000 individuals with CF, and tallied 181 cases of COVID-19. A total of 149 cases were nontransplant, and 32 were posttransplant (28 lung only). Fully 15% of the nontransplant group were over age 40 years, compared with 41% in the transplant group. Homozygous F508del mutations were more common in the posttransplant group (59% vs. 36%). However, lung function, as estimated by the best FEV1 measured in the previous year prior to infection, differed between the nontransplant (73%) and posttransplant (80%) COVID-19 patients.

Across all age groups, hospitalizations were more common in patients with best FEV1 percentage predicted values less than 70% (P = .001). Ms. Cosgriff also expressed concern about the posttransplant group. “Across all outcomes that might be indicative of infection severity – hospitalization, ICU admission, new supplementary oxygen, and non-invasive ventilation – the proportion of the posttransplant group was higher across the board,” she said during her presentation.

There were seven deaths. Ms. Cosgriff noted that there were too few deaths to analyze trends, but she presented a slide showing characteristics of deceased patients. “Factors like being post–lung transplant, being male, having less FEV1 than predicted, being over 40, or having CF-related diabetes, all appear pretty frequently amongst the cohort of people who died,” she said.

Overall, the results of these surveys are encouraging, suggesting that early fears that COVID-19 cases could be more severe among individuals with CF may not have been borne out so far. Dr. Sanders noted in his talk that there aren’t enough cases in the U.S. cohort to show links to risk factors with statistical significance. “But thankfully we’re not seeing a host of negative outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Sanders and Ms Cosgriff have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM NACFC 2020

Home spirometry improved monitoring of cystic fibrosis patients during COVID-19 pandemic

Home spirometry has become increasingly used among cystic fibrosis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, and new research suggests that home devices perform reasonably well. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) values were a bit lower than values seen in clinical spirometry performed in the same patient at a nearby time point, but the procedure reliably picked up decreases in FEV1, potentially helping patients and clinicians spot exacerbations early.

“Home spirometry was sort of a curiosity that was slowly working its way into cystic fibrosis research in 2019, and then all of a sudden in 2020 it became front and center as the only way to continue with clinical monitoring and research in many cases,” Alexander Paynter, MS, a biostatistician at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Therapeutic Development Network Coordinating Center, said during a talk at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

To better determine how closely home spirometry matches clinical spirometry, Mr. Paynter and his colleagues analyzed data from the eICE study, which included 267 cystic fibrosis patients aged 14 and over at 14 cystic fibrosis centers. They were randomized to use home spirometry as an early intervention to detect exacerbations, or to continue usual clinic care with visits to the clinic every 3 months. The dataset includes twice-weekly home spirometry values, with a full-year of follow-up data. The researchers compared the home spirometry data to the clinical data closest in time to it. Clinic spirometry data with no corresponding home data within 7 days were discarded.

There was an estimated difference of –2.01 mL between home and clinic tests, with home spirometry producing lower values (95% confidence interval, –3.56 to –0.45). “There is actually a bias in home spirometry as compared to clinic spirometry,” concluded Mr. Paynter.

One explanation for lower values in home spirometry is that users are inexperienced with the device. If that’s true, then agreement should improve over time, but the researchers didn’t see strong evidence of that. Among 44 patients who completed five clinical visits, there was a difference of –2.97 (standard deviation [SD], 10.51) at baseline, –1.66 at 3 months (SD, 13.49), –3.7 at 6 months (SD, 12.44), –0.86 at 9 months (SD, 13.73), and –0.53 at 12 months (SD, 13.35). Though there was improvement over time, “we don’t find a lot of evidence that this bias completely resolves,” said Mr. Paynter.

In fact, a more likely explanation is the presence of coaching by a technician during clinical spirometry, according to Robert J. Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center at New York University. “When they’re doing it at home, they don’t do it with the same effort, so I think that coaching through telemedicine during the home spirometry would make that difference disappear,” he said when asked to comment on the study.

The researchers found that change-based endpoints were similar between clinic and at-home spirometry. Compared to baseline, the two showed similar declines over time. “The clinic and home observations tend to track each other pretty well. At 6 months, for instance, it’s about a change of three points decrease (in both). But the bad news is that the variability is much greater in home devices,” said Mr. Paynter, noting larger confidence intervals and standard deviation values associated with home spirometry. That could influence future clinical designs that may rely on home spirometry, since a larger confidence interval means reduced power, which could double or even quadruple the number of participants needed to achieve the required power, he said.

But from a clinical standpoint, the ability of home spirometry to consistently detect a change from baseline could be quite valuable to future patient management, according to Dr. Giusti. “It looks like home spirometry will show that kind of a decrease, so that it’s still sensitive to pick up the concern that a patient is getting worse at home,” he said.

That could be useful even after the COVID-19 pandemic passes, as patients continue to embrace home monitoring. Physicians could keep track of patients and keep them focused on their care and treatment through frequent telemedicine visits combined with home spirometry. “I really think home spirometry will keep us more focused on how the patients are doing and make for better outcomes,” said Dr. Giusti.

Mr. Paynter and Dr. Giusti have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Alex Paynter et al. NACFC 2020. Poster 643.

Home spirometry has become increasingly used among cystic fibrosis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, and new research suggests that home devices perform reasonably well. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) values were a bit lower than values seen in clinical spirometry performed in the same patient at a nearby time point, but the procedure reliably picked up decreases in FEV1, potentially helping patients and clinicians spot exacerbations early.

“Home spirometry was sort of a curiosity that was slowly working its way into cystic fibrosis research in 2019, and then all of a sudden in 2020 it became front and center as the only way to continue with clinical monitoring and research in many cases,” Alexander Paynter, MS, a biostatistician at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Therapeutic Development Network Coordinating Center, said during a talk at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

To better determine how closely home spirometry matches clinical spirometry, Mr. Paynter and his colleagues analyzed data from the eICE study, which included 267 cystic fibrosis patients aged 14 and over at 14 cystic fibrosis centers. They were randomized to use home spirometry as an early intervention to detect exacerbations, or to continue usual clinic care with visits to the clinic every 3 months. The dataset includes twice-weekly home spirometry values, with a full-year of follow-up data. The researchers compared the home spirometry data to the clinical data closest in time to it. Clinic spirometry data with no corresponding home data within 7 days were discarded.

There was an estimated difference of –2.01 mL between home and clinic tests, with home spirometry producing lower values (95% confidence interval, –3.56 to –0.45). “There is actually a bias in home spirometry as compared to clinic spirometry,” concluded Mr. Paynter.

One explanation for lower values in home spirometry is that users are inexperienced with the device. If that’s true, then agreement should improve over time, but the researchers didn’t see strong evidence of that. Among 44 patients who completed five clinical visits, there was a difference of –2.97 (standard deviation [SD], 10.51) at baseline, –1.66 at 3 months (SD, 13.49), –3.7 at 6 months (SD, 12.44), –0.86 at 9 months (SD, 13.73), and –0.53 at 12 months (SD, 13.35). Though there was improvement over time, “we don’t find a lot of evidence that this bias completely resolves,” said Mr. Paynter.

In fact, a more likely explanation is the presence of coaching by a technician during clinical spirometry, according to Robert J. Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center at New York University. “When they’re doing it at home, they don’t do it with the same effort, so I think that coaching through telemedicine during the home spirometry would make that difference disappear,” he said when asked to comment on the study.

The researchers found that change-based endpoints were similar between clinic and at-home spirometry. Compared to baseline, the two showed similar declines over time. “The clinic and home observations tend to track each other pretty well. At 6 months, for instance, it’s about a change of three points decrease (in both). But the bad news is that the variability is much greater in home devices,” said Mr. Paynter, noting larger confidence intervals and standard deviation values associated with home spirometry. That could influence future clinical designs that may rely on home spirometry, since a larger confidence interval means reduced power, which could double or even quadruple the number of participants needed to achieve the required power, he said.

But from a clinical standpoint, the ability of home spirometry to consistently detect a change from baseline could be quite valuable to future patient management, according to Dr. Giusti. “It looks like home spirometry will show that kind of a decrease, so that it’s still sensitive to pick up the concern that a patient is getting worse at home,” he said.

That could be useful even after the COVID-19 pandemic passes, as patients continue to embrace home monitoring. Physicians could keep track of patients and keep them focused on their care and treatment through frequent telemedicine visits combined with home spirometry. “I really think home spirometry will keep us more focused on how the patients are doing and make for better outcomes,” said Dr. Giusti.

Mr. Paynter and Dr. Giusti have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Alex Paynter et al. NACFC 2020. Poster 643.

Home spirometry has become increasingly used among cystic fibrosis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, and new research suggests that home devices perform reasonably well. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) values were a bit lower than values seen in clinical spirometry performed in the same patient at a nearby time point, but the procedure reliably picked up decreases in FEV1, potentially helping patients and clinicians spot exacerbations early.

“Home spirometry was sort of a curiosity that was slowly working its way into cystic fibrosis research in 2019, and then all of a sudden in 2020 it became front and center as the only way to continue with clinical monitoring and research in many cases,” Alexander Paynter, MS, a biostatistician at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Therapeutic Development Network Coordinating Center, said during a talk at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

To better determine how closely home spirometry matches clinical spirometry, Mr. Paynter and his colleagues analyzed data from the eICE study, which included 267 cystic fibrosis patients aged 14 and over at 14 cystic fibrosis centers. They were randomized to use home spirometry as an early intervention to detect exacerbations, or to continue usual clinic care with visits to the clinic every 3 months. The dataset includes twice-weekly home spirometry values, with a full-year of follow-up data. The researchers compared the home spirometry data to the clinical data closest in time to it. Clinic spirometry data with no corresponding home data within 7 days were discarded.

There was an estimated difference of –2.01 mL between home and clinic tests, with home spirometry producing lower values (95% confidence interval, –3.56 to –0.45). “There is actually a bias in home spirometry as compared to clinic spirometry,” concluded Mr. Paynter.

One explanation for lower values in home spirometry is that users are inexperienced with the device. If that’s true, then agreement should improve over time, but the researchers didn’t see strong evidence of that. Among 44 patients who completed five clinical visits, there was a difference of –2.97 (standard deviation [SD], 10.51) at baseline, –1.66 at 3 months (SD, 13.49), –3.7 at 6 months (SD, 12.44), –0.86 at 9 months (SD, 13.73), and –0.53 at 12 months (SD, 13.35). Though there was improvement over time, “we don’t find a lot of evidence that this bias completely resolves,” said Mr. Paynter.

In fact, a more likely explanation is the presence of coaching by a technician during clinical spirometry, according to Robert J. Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center at New York University. “When they’re doing it at home, they don’t do it with the same effort, so I think that coaching through telemedicine during the home spirometry would make that difference disappear,” he said when asked to comment on the study.

The researchers found that change-based endpoints were similar between clinic and at-home spirometry. Compared to baseline, the two showed similar declines over time. “The clinic and home observations tend to track each other pretty well. At 6 months, for instance, it’s about a change of three points decrease (in both). But the bad news is that the variability is much greater in home devices,” said Mr. Paynter, noting larger confidence intervals and standard deviation values associated with home spirometry. That could influence future clinical designs that may rely on home spirometry, since a larger confidence interval means reduced power, which could double or even quadruple the number of participants needed to achieve the required power, he said.

But from a clinical standpoint, the ability of home spirometry to consistently detect a change from baseline could be quite valuable to future patient management, according to Dr. Giusti. “It looks like home spirometry will show that kind of a decrease, so that it’s still sensitive to pick up the concern that a patient is getting worse at home,” he said.

That could be useful even after the COVID-19 pandemic passes, as patients continue to embrace home monitoring. Physicians could keep track of patients and keep them focused on their care and treatment through frequent telemedicine visits combined with home spirometry. “I really think home spirometry will keep us more focused on how the patients are doing and make for better outcomes,” said Dr. Giusti.

Mr. Paynter and Dr. Giusti have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Alex Paynter et al. NACFC 2020. Poster 643.

FROM NACFC 2020

Lions and tigers and anteaters? U.S. scientists scan the menagerie for COVID

As COVID-19 cases surge in the United States, one Texas veterinarian has been quietly tracking the spread of the disease – not in people, but in their pets.

Since June, Dr. Sarah Hamer and her team at Texas A&M University have tested hundreds of animals from area households where humans contracted COVID-19. They’ve swabbed dogs and cats, sure, but also pet hamsters and guinea pigs, looking for signs of infection. “We’re open to all of it,” said Dr. Hamer, a professor of epidemiology, who has found at least 19 cases of infection.

One pet that tested positive was Phoenix, a 7-year-old part Siamese cat owned by Kaitlyn Romoser, who works in a university lab. Ms. Romoser, 23, was confirmed to have COVID-19 twice, once in March and again in September. The second time she was much sicker, she said, and Phoenix was her constant companion.

“If I would have known animals were just getting it everywhere, I would have tried to distance myself, but he will not distance himself from me,” Ms. Romoser said. “He sleeps in my bed with me. There was absolutely no social distancing.”

Across the country, veterinarians and other researchers are scouring the animal kingdom for signs of the virus that causes COVID-19. At least 2,000 animals in the U.S. have been tested for the coronavirus since the pandemic began, according to federal records. Cats and dogs that were exposed to sick owners represent most of the animals tested and 80% of the positive cases found.

But scientists have cast a wide net investigating other animals that could be at risk. In states from California to Florida, researchers have tested species ranging from farmed minks and zoo cats to unexpected critters like dolphins, armadillos, and anteaters.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture keeps an official tally of confirmed animal COVID cases that stands at several dozen. But that list is a vast undercount of actual infections. In Utah and Wisconsin, for instance, more than 14,000 minks died in recent weeks after contracting COVID infections initially spread by humans.

So far, there’s limited evidence that animals are transmitting the virus to people. Veterinarians emphasize that pet owners appear to be in no danger from their animal companions and should continue to love and care for them. But scientists say continued testing is one way to remain vigilant in the face of a previously unknown pathogen.

“We just know that coronaviruses, as a family, infect a lot of species, mostly mammals,” said Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, a professor of environmental and occupational health sciences and the director of the University of Washington Center for One Health Research in Seattle. “It makes sense to take a species-spanning approach and look at a wide spectrum.”

Much of the testing has been rooted in scientific curiosity. Since the pandemic began, a major puzzle has been how the virus, which likely originated in bats, spread to humans. A leading theory is that it jumped to an intermediate species, still unknown, and then to people.

In April, a 4-year-old Malayan tiger at the Bronx Zoo tested positive for COVID-19 in a first-of-its-kind case after seven big cats showed signs of respiratory illness. The tiger, Nadia, contracted the virus from a caretaker, federal health officials said. Four other tigers and three African lions were also confirmed to be infected.

In Washington state, the site of the first U.S. outbreak in humans, scientists rushed to design a COVID test for animals in March, said Charlie Powell, a spokesperson for the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman. “We knew with warm-blooded animals, housed together, there’s going to be some cross-infection,” he said. Tests for animals use different reagent compounds than those used for tests in people, so they don’t deplete the human supply, Mr. Powell added.

Since spring, the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory has tested nearly 80 animals, including 38 dogs, 29 cats, 2 ferrets, a camel, and 2 tamanduas, a type of anteater. The lab also tested six minks from the outbreak in Utah, five of which accounted for the lab’s only positive tests.

All told, nearly 1,400 animals have been tested for COVID-19 through the National Animal Health Laboratory Network or private labs, said Lyndsay Cole, a spokesperson for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. More than 400 animals have been tested through the National Veterinary Services Laboratories. At least 250 more have been tested through academic research projects.

Most of the tests have been in household cats and dogs with suspicious respiratory symptoms. In June, the USDA reported that a dog in New York was the first pet dog to test positive for the coronavirus after falling ill and struggling to breathe. The dog, a 7-year-old German shepherd named Buddy, later died. Officials determined he’d contracted the virus from his owner.

Neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the USDA recommends routine testing for house pets or other animals – but that hasn’t stopped owners from asking, said Dr. Douglas Kratt, president of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

“The questions have become a little more consistent at my practice,” he said. “People do want to know about COVID-19 and their pets. Can their pet pick it up at a clinic or boarding or in doggie day care?”

The answer, so far, is that humans are the primary source of infection in pets. In September, a small, unpublished study from the University of Guelph in Canada found that companion cats and dogs appeared to be infected by their sick owners, judging by antibodies to the coronavirus detected in their blood.

In Texas, Dr. Hamer started testing animals from households where someone had contracted COVID-19 to learn more about transmission pathways. “Right now, we’re very much trying to describe what’s happening in nature,” she said.

So far, most of the animals – including Phoenix, Ms. Romoser’s cat – have shown no signs of illness or disease. That’s true so far for many species of animals tested for COVID-19, veterinarians said. Most nonhuman creatures appear to weather COVID infection with mild symptoms like sniffles and lethargy, if any.

Still, owners should apply best practices for avoiding COVID infection to pets, too, Dr. Kratt said. Don’t let pets come into contact with unfamiliar animals, he suggested. Owners should wash their hands frequently and avoid nuzzling and other very close contact, if possible.

Cats appear to be more susceptible to COVID-19 than dogs, researchers said. And minks, which are farmed in the U.S. and elsewhere for their fur, appear quite vulnerable.

In the meantime, the list of creatures tested for COVID-19 – whether for illness or science – is growing. In Florida, 22 animals had been tested as of early October, including 3 wild dolphins, 2 civets, 2 clouded leopards, a gorilla, an orangutan, an alpaca, and a bush baby, state officials said.

In California, 29 animals had been tested by the end of September, including a meerkat, a monkey, and a coatimundi, a member of the raccoon family.

In Seattle, a plan to test orcas, or killer whales, in Puget Sound was called off at the last minute after a member of the scientific team was exposed to COVID-19 and had to quarantine, said Dr. Joe Gaydos, a senior wildlife veterinarian and science director for the SeaDoc Society, a conservation program at the University of California-Davis. The group missed its September window to locate the animals and obtain breath and fecal samples for analysis.

No one thinks marine animals will play a big role in the pandemic decimating the human population, Dr. Gaydos said. But testing many creatures on both land and sea is vital.

“We don’t know what this virus is going to do or can do,” Dr. Gaydos said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

As COVID-19 cases surge in the United States, one Texas veterinarian has been quietly tracking the spread of the disease – not in people, but in their pets.

Since June, Dr. Sarah Hamer and her team at Texas A&M University have tested hundreds of animals from area households where humans contracted COVID-19. They’ve swabbed dogs and cats, sure, but also pet hamsters and guinea pigs, looking for signs of infection. “We’re open to all of it,” said Dr. Hamer, a professor of epidemiology, who has found at least 19 cases of infection.

One pet that tested positive was Phoenix, a 7-year-old part Siamese cat owned by Kaitlyn Romoser, who works in a university lab. Ms. Romoser, 23, was confirmed to have COVID-19 twice, once in March and again in September. The second time she was much sicker, she said, and Phoenix was her constant companion.

“If I would have known animals were just getting it everywhere, I would have tried to distance myself, but he will not distance himself from me,” Ms. Romoser said. “He sleeps in my bed with me. There was absolutely no social distancing.”

Across the country, veterinarians and other researchers are scouring the animal kingdom for signs of the virus that causes COVID-19. At least 2,000 animals in the U.S. have been tested for the coronavirus since the pandemic began, according to federal records. Cats and dogs that were exposed to sick owners represent most of the animals tested and 80% of the positive cases found.

But scientists have cast a wide net investigating other animals that could be at risk. In states from California to Florida, researchers have tested species ranging from farmed minks and zoo cats to unexpected critters like dolphins, armadillos, and anteaters.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture keeps an official tally of confirmed animal COVID cases that stands at several dozen. But that list is a vast undercount of actual infections. In Utah and Wisconsin, for instance, more than 14,000 minks died in recent weeks after contracting COVID infections initially spread by humans.

So far, there’s limited evidence that animals are transmitting the virus to people. Veterinarians emphasize that pet owners appear to be in no danger from their animal companions and should continue to love and care for them. But scientists say continued testing is one way to remain vigilant in the face of a previously unknown pathogen.

“We just know that coronaviruses, as a family, infect a lot of species, mostly mammals,” said Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, a professor of environmental and occupational health sciences and the director of the University of Washington Center for One Health Research in Seattle. “It makes sense to take a species-spanning approach and look at a wide spectrum.”

Much of the testing has been rooted in scientific curiosity. Since the pandemic began, a major puzzle has been how the virus, which likely originated in bats, spread to humans. A leading theory is that it jumped to an intermediate species, still unknown, and then to people.

In April, a 4-year-old Malayan tiger at the Bronx Zoo tested positive for COVID-19 in a first-of-its-kind case after seven big cats showed signs of respiratory illness. The tiger, Nadia, contracted the virus from a caretaker, federal health officials said. Four other tigers and three African lions were also confirmed to be infected.

In Washington state, the site of the first U.S. outbreak in humans, scientists rushed to design a COVID test for animals in March, said Charlie Powell, a spokesperson for the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman. “We knew with warm-blooded animals, housed together, there’s going to be some cross-infection,” he said. Tests for animals use different reagent compounds than those used for tests in people, so they don’t deplete the human supply, Mr. Powell added.

Since spring, the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory has tested nearly 80 animals, including 38 dogs, 29 cats, 2 ferrets, a camel, and 2 tamanduas, a type of anteater. The lab also tested six minks from the outbreak in Utah, five of which accounted for the lab’s only positive tests.

All told, nearly 1,400 animals have been tested for COVID-19 through the National Animal Health Laboratory Network or private labs, said Lyndsay Cole, a spokesperson for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. More than 400 animals have been tested through the National Veterinary Services Laboratories. At least 250 more have been tested through academic research projects.

Most of the tests have been in household cats and dogs with suspicious respiratory symptoms. In June, the USDA reported that a dog in New York was the first pet dog to test positive for the coronavirus after falling ill and struggling to breathe. The dog, a 7-year-old German shepherd named Buddy, later died. Officials determined he’d contracted the virus from his owner.

Neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the USDA recommends routine testing for house pets or other animals – but that hasn’t stopped owners from asking, said Dr. Douglas Kratt, president of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

“The questions have become a little more consistent at my practice,” he said. “People do want to know about COVID-19 and their pets. Can their pet pick it up at a clinic or boarding or in doggie day care?”

The answer, so far, is that humans are the primary source of infection in pets. In September, a small, unpublished study from the University of Guelph in Canada found that companion cats and dogs appeared to be infected by their sick owners, judging by antibodies to the coronavirus detected in their blood.

In Texas, Dr. Hamer started testing animals from households where someone had contracted COVID-19 to learn more about transmission pathways. “Right now, we’re very much trying to describe what’s happening in nature,” she said.

So far, most of the animals – including Phoenix, Ms. Romoser’s cat – have shown no signs of illness or disease. That’s true so far for many species of animals tested for COVID-19, veterinarians said. Most nonhuman creatures appear to weather COVID infection with mild symptoms like sniffles and lethargy, if any.

Still, owners should apply best practices for avoiding COVID infection to pets, too, Dr. Kratt said. Don’t let pets come into contact with unfamiliar animals, he suggested. Owners should wash their hands frequently and avoid nuzzling and other very close contact, if possible.

Cats appear to be more susceptible to COVID-19 than dogs, researchers said. And minks, which are farmed in the U.S. and elsewhere for their fur, appear quite vulnerable.

In the meantime, the list of creatures tested for COVID-19 – whether for illness or science – is growing. In Florida, 22 animals had been tested as of early October, including 3 wild dolphins, 2 civets, 2 clouded leopards, a gorilla, an orangutan, an alpaca, and a bush baby, state officials said.

In California, 29 animals had been tested by the end of September, including a meerkat, a monkey, and a coatimundi, a member of the raccoon family.

In Seattle, a plan to test orcas, or killer whales, in Puget Sound was called off at the last minute after a member of the scientific team was exposed to COVID-19 and had to quarantine, said Dr. Joe Gaydos, a senior wildlife veterinarian and science director for the SeaDoc Society, a conservation program at the University of California-Davis. The group missed its September window to locate the animals and obtain breath and fecal samples for analysis.

No one thinks marine animals will play a big role in the pandemic decimating the human population, Dr. Gaydos said. But testing many creatures on both land and sea is vital.

“We don’t know what this virus is going to do or can do,” Dr. Gaydos said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

As COVID-19 cases surge in the United States, one Texas veterinarian has been quietly tracking the spread of the disease – not in people, but in their pets.

Since June, Dr. Sarah Hamer and her team at Texas A&M University have tested hundreds of animals from area households where humans contracted COVID-19. They’ve swabbed dogs and cats, sure, but also pet hamsters and guinea pigs, looking for signs of infection. “We’re open to all of it,” said Dr. Hamer, a professor of epidemiology, who has found at least 19 cases of infection.

One pet that tested positive was Phoenix, a 7-year-old part Siamese cat owned by Kaitlyn Romoser, who works in a university lab. Ms. Romoser, 23, was confirmed to have COVID-19 twice, once in March and again in September. The second time she was much sicker, she said, and Phoenix was her constant companion.

“If I would have known animals were just getting it everywhere, I would have tried to distance myself, but he will not distance himself from me,” Ms. Romoser said. “He sleeps in my bed with me. There was absolutely no social distancing.”

Across the country, veterinarians and other researchers are scouring the animal kingdom for signs of the virus that causes COVID-19. At least 2,000 animals in the U.S. have been tested for the coronavirus since the pandemic began, according to federal records. Cats and dogs that were exposed to sick owners represent most of the animals tested and 80% of the positive cases found.

But scientists have cast a wide net investigating other animals that could be at risk. In states from California to Florida, researchers have tested species ranging from farmed minks and zoo cats to unexpected critters like dolphins, armadillos, and anteaters.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture keeps an official tally of confirmed animal COVID cases that stands at several dozen. But that list is a vast undercount of actual infections. In Utah and Wisconsin, for instance, more than 14,000 minks died in recent weeks after contracting COVID infections initially spread by humans.

So far, there’s limited evidence that animals are transmitting the virus to people. Veterinarians emphasize that pet owners appear to be in no danger from their animal companions and should continue to love and care for them. But scientists say continued testing is one way to remain vigilant in the face of a previously unknown pathogen.

“We just know that coronaviruses, as a family, infect a lot of species, mostly mammals,” said Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, a professor of environmental and occupational health sciences and the director of the University of Washington Center for One Health Research in Seattle. “It makes sense to take a species-spanning approach and look at a wide spectrum.”

Much of the testing has been rooted in scientific curiosity. Since the pandemic began, a major puzzle has been how the virus, which likely originated in bats, spread to humans. A leading theory is that it jumped to an intermediate species, still unknown, and then to people.

In April, a 4-year-old Malayan tiger at the Bronx Zoo tested positive for COVID-19 in a first-of-its-kind case after seven big cats showed signs of respiratory illness. The tiger, Nadia, contracted the virus from a caretaker, federal health officials said. Four other tigers and three African lions were also confirmed to be infected.

In Washington state, the site of the first U.S. outbreak in humans, scientists rushed to design a COVID test for animals in March, said Charlie Powell, a spokesperson for the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman. “We knew with warm-blooded animals, housed together, there’s going to be some cross-infection,” he said. Tests for animals use different reagent compounds than those used for tests in people, so they don’t deplete the human supply, Mr. Powell added.

Since spring, the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory has tested nearly 80 animals, including 38 dogs, 29 cats, 2 ferrets, a camel, and 2 tamanduas, a type of anteater. The lab also tested six minks from the outbreak in Utah, five of which accounted for the lab’s only positive tests.

All told, nearly 1,400 animals have been tested for COVID-19 through the National Animal Health Laboratory Network or private labs, said Lyndsay Cole, a spokesperson for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. More than 400 animals have been tested through the National Veterinary Services Laboratories. At least 250 more have been tested through academic research projects.

Most of the tests have been in household cats and dogs with suspicious respiratory symptoms. In June, the USDA reported that a dog in New York was the first pet dog to test positive for the coronavirus after falling ill and struggling to breathe. The dog, a 7-year-old German shepherd named Buddy, later died. Officials determined he’d contracted the virus from his owner.

Neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the USDA recommends routine testing for house pets or other animals – but that hasn’t stopped owners from asking, said Dr. Douglas Kratt, president of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

“The questions have become a little more consistent at my practice,” he said. “People do want to know about COVID-19 and their pets. Can their pet pick it up at a clinic or boarding or in doggie day care?”

The answer, so far, is that humans are the primary source of infection in pets. In September, a small, unpublished study from the University of Guelph in Canada found that companion cats and dogs appeared to be infected by their sick owners, judging by antibodies to the coronavirus detected in their blood.

In Texas, Dr. Hamer started testing animals from households where someone had contracted COVID-19 to learn more about transmission pathways. “Right now, we’re very much trying to describe what’s happening in nature,” she said.

So far, most of the animals – including Phoenix, Ms. Romoser’s cat – have shown no signs of illness or disease. That’s true so far for many species of animals tested for COVID-19, veterinarians said. Most nonhuman creatures appear to weather COVID infection with mild symptoms like sniffles and lethargy, if any.

Still, owners should apply best practices for avoiding COVID infection to pets, too, Dr. Kratt said. Don’t let pets come into contact with unfamiliar animals, he suggested. Owners should wash their hands frequently and avoid nuzzling and other very close contact, if possible.

Cats appear to be more susceptible to COVID-19 than dogs, researchers said. And minks, which are farmed in the U.S. and elsewhere for their fur, appear quite vulnerable.

In the meantime, the list of creatures tested for COVID-19 – whether for illness or science – is growing. In Florida, 22 animals had been tested as of early October, including 3 wild dolphins, 2 civets, 2 clouded leopards, a gorilla, an orangutan, an alpaca, and a bush baby, state officials said.

In California, 29 animals had been tested by the end of September, including a meerkat, a monkey, and a coatimundi, a member of the raccoon family.

In Seattle, a plan to test orcas, or killer whales, in Puget Sound was called off at the last minute after a member of the scientific team was exposed to COVID-19 and had to quarantine, said Dr. Joe Gaydos, a senior wildlife veterinarian and science director for the SeaDoc Society, a conservation program at the University of California-Davis. The group missed its September window to locate the animals and obtain breath and fecal samples for analysis.

No one thinks marine animals will play a big role in the pandemic decimating the human population, Dr. Gaydos said. But testing many creatures on both land and sea is vital.

“We don’t know what this virus is going to do or can do,” Dr. Gaydos said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Common SARS-CoV-2 mutation may be making COVID-19 more contagious

Most SARS-CoV-2 virus strains feature a specific mutation that makes them more transmissible, to the point that these strains now predominate globally, new evidence shows.

In contrast to a greater variety of strains early in the pandemic, now 99.9% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the study feature the D614G mutation on the spike protein. In addition, people infected with a D614G strain have higher nasopharynx viral loads at diagnosis.

It’s not all bad news. This single-point mutation was not associated with worse clinical COVID-19 severity. Also, the mutation isn’t expected to interfere with the efficacy any of the antibody cocktails, small molecule therapies or vaccines in development.

Furthermore, “as bad as SARS-CoV-2 is, we may have dodged a bullet in terms of how quickly it mutates,” study author Ilya Finkelstein, PhD, said in an interview. This virus mutates much slower than HIV, for example, giving researchers a greater chance to stay one step ahead, he said.

The study was published online Oct. 30 in the journal mBio.

Molecular sleuthing

The research was possible because colleagues at the Houston Methodist Hospital system sequenced the genome of 5085 SARS-CoV-2 strains early in the outbreak and during a second wave of infection over the summer, Dr. Finkelstein said.

The unique data source also includes information from plasma, convalescent plasma, and patient outcomes. Studying a large and diverse population in a major metropolitan area like Houston helps create a “molecular fingerprint” for the virus that will continue to be very useful, said Dr. Finkelstein, a researcher and director of the Finkelstein Lab at the University of Texas, Austin.