User login

Bringing you the latest case reports, original research, clinical trial reviews, perspectives, patient resources, and more.

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) survival trends

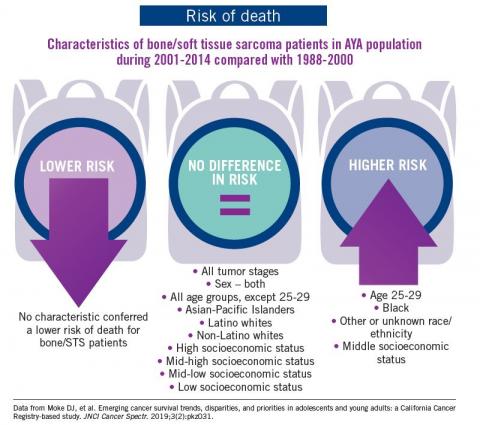

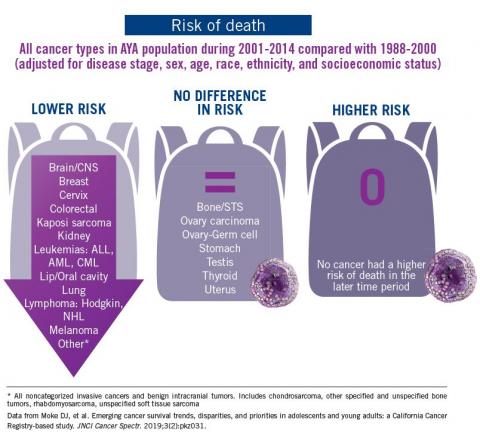

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

Conference Coverage: ASCO 2019

Behind Olaratumab's Phase 3 Disappointment

ANNOUNCE, the phase 3 trial designed to confirm the clinical benefit of olaratumab in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (STS), failed to meet its primary endpoint of overall survival (OS) in all STS histologies and the leiomyosarcoma population. The previous phase 1b/2 signal-finding study of olaratumab had achieved an unprecedented improvement in OS, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) awarded olaratumab accelerated approval in October 2016. By December 2018, olaratumab received additional accelerated, conditional, and full approvals in more than 40 countries worldwide. William D. Tap, MD, chief of the Sarcoma Medical Oncology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, presented the phase 3 results and provided some explanations for the findings during the plenary session at ASCO.

ANNOUNCE (NCT02451943), which was designed and enrolled prior to olaratumab receiving accelerated approval, opened in September 2015 and completed accrual 10 months later in July 2016. Investigators randomized and treated 509 patients with advanced STS not amenable to curative therapy, 258 patients in the olaratumab-doxorubicin arm and 251 in the placebo-doxorubicin arm. Most patients (46%) had leiomyosarcoma, followed by liposarcoma (18%), pleomorphic sarcoma (13%), and 24% of the patient population had 26 unique histologies. Three-quarters of the patients had no prior systemic therapy.

Results

As of the data cutoff on December 5, 2018, there were no survival differences in the intention-to-treat population, in the total STS population nor in the leiomyosarcoma subpopulation, with olaratumab-doxorubicin compared to placebo-doxorubicin. For the total STS population, median OS with olaratumab- doxorubicin was 20.4 months and with placebo-doxorubicin 19.7 months. “This is the highest survival rate described to date in any phase 3 sarcoma study,” Dr. Tap said. “It is of particular interest as ANNOUNCE did not mandate treatment in the first line.” In the leiomyosarcoma population, median OS was 21.6 months with olaratumab and 21.9 months with placebo. The secondary endpoints of progression-free survival (PFS), overall response rate, and disease control rate did not favor olaratumab either.

Investigators are examining the relationship between PDGFRα expression and OS in ANNOUNCE. PDGFRα-positive tumors tended to do worse with olaratumab than PDGFRα-negative tumors. The investigators noticed a 6-month difference in OS between these populations favoring PDGFRα-negative tumors. Additional biomarker analyses are ongoing.

A large and concerted effort is underway, Dr. Tap said, to understand the results of the ANNOUNCE study alone and in context with the phase 1b/2 study. “There are no noted discrepancies in study conduct or data integrity which could explain these findings or the differences between the two studies.”

Possible explanations

The designs of the phase 1b/2 and phase 3 studies had some important differences. The phase 1b/2 study was a small, open-label, US-centric study (10 sites) that did not include a placebo or subtype- specified analyses. Its primary endpoint was PFS, it did not have a loading dose of olaratumab, and it specified the timing of dexrazoxane administration after 300 mg/m2 of doxorubicin.

ANNOUNCE, on the other hand, was a large (n=509), international (110 study sites), double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that had outcomes evaluated in STS and leiomyosarcoma. Its primary endpoint was OS, it had a loading dose of olaratumab of 20 mg/kg, and there was no restriction as to the timing of dexrazoxane administration.

Dr. Tap pointed out that in ANNOUNCE it was difficult to predict or control for factors that may have had an unanticipated influence on outcomes, such as albumin levels as a surrogate for disease burden and behavior of PDGFRα status. It is possible, he said, that olaratumab has no activity in STS and that the phase 1b/2 results were due to, among other things, the small sample size, numerous represented histologies with disparate clinical behavior, and the effect of subtype-specific therapies on overall survival, given subsequently or even by chance. On the other hand, it is also possible, he said, that olaratumab has some activity in STS, with outcomes being affected by the heterogeneity of the study populations, differences in trial design, and the performance of the ANNOUNCE control arm. Whatever the case, he said, accelerated approval allowed patients to have access to a potentially life-prolonging drug with little added toxicity.

Discussion

In the expert discussion following the presentation, Jaap Verweij, MD, PhD, of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, congratulated the investigators for performing the study at an unprecedented pace. He commented that lumping STS subtypes together is problematic, as different histological subtypes behave as though they are different diseases. Small numbers of each tumor subtype and subtypes with slow tumor growth can impact trial outcomes. In the phase 1b/2 and phase 3 trials, 26 different subtypes were represented in each study. Dr. Verweij pointed out this could have made a big difference in the phase 1b/2 study, in which there were only 66 patients in each arm.

It is striking to note, he said, that without exception, phase 2 randomized studies in STS involving doxorubicin consistently overestimated and wrongly predicted PFS in the subsequent phase 3 studies. And the situation is similar for OS. The results of the ANNOUNCE study are no exception, he added. “Taken together, these studies indicate that phase 2 studies in soft tissue sarcomas, certainly those involving additions of drugs to doxorubicin, even if randomized, should be interpreted with great caution,” he said.

SOURCE: Tap WD, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr LBA3)

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. Tap reported research funding from Lilly and Dr. Verweij had nothing to report related to this study. Abstract coauthors disclosed numerous financial relationships, including consulting/advisory roles and/or research funding from Lilly, and several were employed by Lilly.

Addition of Temozolomide May Improve Outcomes in RMS

Investigators from the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG) found that the addition of temozolomide (T) to vincristine and irinotecan (VI) may improve outcomes in adults and children with relapsed or refractory rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). Principal investigator of the study, Anne Sophie Defachelles, MD, pediatric oncologist at the Centre Oscar Lambret in Lille, France, presented the results on behalf of the EpSSG.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of VI and VIT regimens, defined as objective response (OR)—complete response (CR) plus partial response (PR)—after 2 cycles. Secondary objectives were progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety in each arm, and the relative treatment effect of VIT compared to VI in terms of OR, survival, and safety.

The international, randomized (1:1), open-label, phase 2 trial (VIT-0910; NCT01355445) was conducted at 37 centers in 5 countries. Patients ages 6 months to 50 years with RMS were eligible. They could not have had prior irinotecan or temozolomide. A 2015 protocol amendment limited enrollment to patients at relapse and increased the enrollment goal by 40 patients. After the 2015 amendment, patients with refractory disease were no longer eligible.

From January 2012 to April 2018, investigators enrolled 120 patients, 60 on each arm. Two patients in the VI arm were not treated. Patients were a median age of 10.5 years in the VI arm and 12 years in the VIT arm, 92% (VI) and 87% (VIT) had relapsed disease, 8% (VI) and 13% (VIT) had refractory disease, and 55% (VI) and 68% (VIT) had metastatic disease at study entry.

Results

Patients achieved an OR rate of 44% (VIT) and 31% (VI) for the whole population, one-sided P value <.0001. The adjusted odds ratio for the whole population was 0.50, P=.09. PFS was 4.7 months (VIT) and 3.2 months (VI), “a nearly significant reduction in the risk of progression,” Dr. Defachelles noted. Median OS was 15.0 months (VIT) and 10.3 months (VI), which amounted to “a large and significant reduction in the risk of death,” she said. The adjusted hazard ratio was 0.55, P=.006.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher were more frequent in the VIT arm, with hematologic toxicity the most frequent (81% for VIT, 59% for VI), followed by gastrointestinal adverse events. “VIT was significantly more toxic than VI,” Dr. Defachelles observed, “but the toxicity was manageable.”

“VIT is now the standard treatment in Europe for relapsed rhabdomyosarcoma and will be the control arm in the multiarm, multistage RMS study for relapsed patients,” she said.

In a discussion following the presentation, Lars M. Wagner, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, pointed out that the study was not powered for the PFS and OS assessments. These were secondary objectives that should be considered exploratory. Therefore, he said, the outcome data is not conclusive. The role of temozolomide in RMS is also unclear, given recent negative results in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic RMS (Malempati et al, Cancer 2019). And he said it’s uncertain how these results apply to patients who received irinotecan upfront for RMS.

SOURCE: Defachelles AS, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 10000)

The study was sponsored by Centre Oscar Lambret and SFCE (Société Française de Lutte contre les Cancers et Lucémies de l’Enfant et de l’Adolescent) served as collaborator.

Drs. Defachelles and Wagner had no relationships to disclose. A few coauthors had advisory/consulting or speaker roles for various commercial interests, including two for Merck (temozolomide).

Pazopanib Increases Pathologic Necrosis Rates in STS

Pazopanib added to a regimen of preoperative chemoradiation in non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma (NRSTS) significantly increased the rate of near-complete pathologic response in both children and adults with intermediate or high-risk disease. Pazopanib, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, works in multiple signaling pathways involved in tumorigenesis— VEGFR-1, -2, -3, PDGFRα/β, and c-kit. A phase 3 study demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced STS patients and was the basis for its approval in the US and elsewhere for treatment of this patient population. Preclinical data suggest synergy between pazopanib and cytotoxic chemotherapy, forming the rationale for the current trial with neoadjuvant pazopanib added to chemoradiation.

According to the investigators, the trial (ARST1321) is the first ever collaborative study codeveloped, written, and conducted by pediatric (Children’s Oncology Group) and adult (NRG Oncology) cancer cooperative groups (NCT02180867). Aaron R. Weiss, MD, of the Maine Medical Center in Portland and study cochair, presented the data for the chemotherapy arms at ASCO. The primary objectives of the study were to determine the feasibility of preoperative chemoradiation with or without pazopanib and to compare the rates of complete pathologic response in patients receiving radiation or chemoradiation with or without pazopanib. Pathologic necrosis rates of 90% or better have been found to be predictive of outcome in STS.

Patients with metastatic or non-metastatic NRSTS were eligible to enroll if they had initially unresectable extremity or trunk tumors with the expectation that they would be resectable after therapy. Patients had to be 2 years or older— there was no upper age limit—and had to be able to swallow a tablet whole. The dose-finding phase of the study determined the pediatric dose to be 350 mg/m2 and the adult dose to be 600 mg/m2, both taken orally and once daily. Patients in the chemotherapy cohort were then randomized to receive chemotherapy—ifosfamide and doxorubicin—with or without pazopanib. At 4 weeks, patients in both arms received preoperative radiotherapy (45 Gy in 25 fractions), and at week 13, surgery of the primary site if they did not have progressive disease. After surgery, patients received continuation therapy with or without pazopanib according to their randomization arm. Upon completion and recovery from the continuation therapy, patients could receive surgery/radiotherapy of their metastatic sites.

Results

As of the June 30, 2018, cutoff, 81 patients were enrolled on the chemotherapy arms: 42 in the pazopanib plus chemoradiation arm and 39 in the chemoradiation-only arm. Sixty-one percent of all patients were 18 years or older, and the median age was 20.3 years. Most patients (73%) did not have metastatic disease, and the major histologies represented were synovial sarcoma (49%) and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (25%).

At week 13, patients in the pazopanib arm showed significant improvement, with 14 (58%) of those evaluated having pathologic necrosis of at least 90%, compared with 4 (22%) in the chemoradiation-only arm (P=.02). The study was closed to further accrual.

Eighteen patients were not evaluable for pathologic response and 21 were pending pathologic evaluation at week 13. Radiographic response rates were not statistically significant on either arm. No complete responses (CR) were achieved in the pazopanib arm, but 14 patients (52%) achieved a partial response (PR) and 12 (44%) had stable disease (SD). In the chemoradiation-only arm, 2 patients (8%) achieved a CR, 12 (50%) a PR, and 8 (33%) SD. Fifteen patients in each arm were not evaluated for radiographic response.

The pazopanib arm experienced more febrile neutropenia and myelotoxicity during induction and continuation phases than the chemoradiation-only arm. In general, investigators indicated pazopanib combined with chemoradiation was well tolerated and no unexpected toxicities arose during the trial.

In the post-presentation discussion, Dr. Raphael E. Pollock, MD, PhD, of The Ohio State University, called it a tremendous challenge to interdigitate primary local therapies in systemic approaches, particularly in the neoadjuvant context. He pointed out that in an earlier study, a 95% to 100% necrosis level was needed to achieve a significant positive impact on outcomes and perhaps a subsequent prospective trial could determine the best level. He questioned whether the availability of only 60% of patient responses could affect the conclusions and whether the high number of toxicities (73.8% grade 3/4 with pazopanib) might be too high to consider the treatment for most patients, given the intensity of the regimen.

SOURCE: Weiss AR, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11002)

The study was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute.

Drs. Weiss and Pollock had no relationships with commercial interests to disclose. A few investigators disclosed advisory, consulting, or research roles with pharmaceutical companies, including one who received institutional research funding from Novartis (pazopanib).

Gemcitabine Plus Pazopanib a Potential Alternative in STS

In a phase 2 study of gemcitabine with pazopanib (G+P) or gemcitabine with docetaxel (G+D), investigators concluded the combination with pazopanib can be considered an alternative to that with docetaxel in select patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (STS). They reported similar progression-free survival (PFS) and rate of toxicity for the two regimens. Neeta Somaiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, presented the findings of the investigator-initiated effort (NCT01593748) at ASCO.

The objective of the study, conducted at 10 centers across the United States, was to examine the activity of pazopanib when combined with gemcitabine as an alternative to the commonly used gemcitabine plus docetaxel regimen. Pazopanib is a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor with efficacy in non-adipocytic STS. Adult patients with metastatic or locally advanced non-adipocytic STS with ECOG performance of 0 or 1 were eligible. Patients had to have received prior anthracycline exposure unless it was contraindicated. The 1:1 randomization included stratification for pelvic radiation and leiomyosarcoma histology, which was felt to have a higher response rate with the pazopanib regimen.

The investigators enrolled 90 patients, 45 in each arm. Patients were a mean age of 56 years, and there was no difference in age or gender distribution between the arms. Patients with leiomyosarcoma (31% overall) or prior pelvic radiation (11% overall) were similar between the arms. The overall response rate using RECIST 1.1 criteria was partial response (PR) in 8 of 44 evaluable patients (18%) in the G+D arm and 5 of 43 evaluable patients (12%) in the G+P arm. Stable disease (SD) was observed in 21 patients (48%) in the G+D arm and 24 patients (56%) in the G+P arm. This amounted to a clinical benefit rate (PR + SD) of 66% and 68% for the G+D and G+P arms, respectively (Fisher’s exact test, P>.99). The median PFS was 4.1 months on both arms and the difference in median overall survival— 15.9 months in the G+D arm and 12.4 months in the G+P arm—was not statistically significant.

Adverse events (AEs) of grade 3 or higher occurred in 19.9% of patients on G+D and 20.6% on G+P. Serious AEs occurred in 33% (G+D) and 22% (G+P). Dose reductions were necessary in 80% of patients on G+P and doses were held in 93%. Dr. Somaiah explained that this may have been because the starting dose of gemcitabine and pazopanib (1000 mg/m2 of gemcitabine on days 1 and 8 and 800 mg of pazopanib) was “probably higher than what we should have started at.” The rate of doses held was also higher in the pazopanib arm (93%) compared with the docetaxel arm (58%). This was likely because pazopanib was a daily dosing, so if there was a toxicity it was more likely to be held than docetaxel, she observed. Grade 3 or higher toxicities occurring in 5% or more of patients in either arm consisted generally of cytopenias and fatigue. The G+P arm experienced a high amount of neutropenia, most likely because this arm did not receive granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) support, as opposed to the G+D arm.

Dr. Somaiah pointed out that the 12% response rate for the G+P combination is similar to what has been previously presented and higher than single-agent gemcitabine or pazopanib, but not higher than the G+D combination. The PFS of 4.1 months was less than anticipated, she added, but it was similar on both arms. The investigators believe the G+P combination warrants further exploration.

SOURCE: Somaiah N, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11008)

The study was sponsored by the Medical University of South Carolina, with Novartis as collaborator.

Dr. Somaiah disclosed Advisory Board roles for Blueprint, Deciphera, and Bayer. Abstract coauthors disclosed advisory/consulting roles or research funding from various commercial interests, including Novartis (pazopanib) and Pfizer (gemcitabine).

rEECur Trial Finding Optimal Chemotherapy Regimen for Ewing Sarcoma

Interim results of the first and largest randomized trial in patients with refractory or recurrent Ewing sarcoma (ES), the rEECur trial, are guiding the way to finding the optimal chemotherapy regimen to treat the disease. Until now, there has been little prospective evidence and no randomized data to guide treatment choices in relapsed or refractory patients, and hence no real standard of care, according to the presentation at ASCO. Several molecularly targeted therapies are emerging, and they require a standardized chemotherapy backbone against which they can be tested.

The rEECur trial (ISRCTN36453794) is a multi-arm, multistage phase 2/3 “drop-a-loser” randomized trial designed to find the standard of care. The trial compares 4 chemotherapy regimens to each other and drops the least effective one after 50 patients per arm are enrolled and evaluated. The 3 remaining regimens continue until at least 75 patients on each arm are enrolled and evaluated, and then another arm would be dropped. The 2 remaining regimens continue to phase 3 evaluation. Four regimens are being tested at 8 centers in 17 countries: topotecan/ cyclophosphamide (TC), irinotecan/temozolomide (IT), gemcitabine/docetaxel (GD), and ifosfamide (IFOS). The primary objective is to identify the optimal regimen based on a balance between efficacy and toxicity. Martin G. McCabe, MB BChir, PhD, of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, presented the results on behalf of the investigators of the rEECur trial.

Results

Two hundred twenty patients 4 years or older and younger than 50 years with recurrent or refractory histologically confirmed ES of bone or soft tissue were randomized to receive GD (n=72) or TC, IT, or IFOS (n=148). Sixty-two GD patients and 123 TC/IT/IFOS patients were included in the primary outcome analysis. Patients were predominantly male (70%), with a median age of 19 years (range, 4 to 49). About two-thirds (67.3%) were post-pubertal. Most patients (85%) were primary refractory or experienced their first disease recurrence, and 89% had measurable disease.

Investigators assessed the primary outcome of objective response after 4 cycles of therapy and found 11% of patients treated with GD responded compared to 24% in the other 3 arms combined. When they subjected the data to Bayesian analysis, there was a 25% chance that the response rate in the GD arm was better than the response in Arm A, a 2% chance that it was better than Arm B, and a 3% chance that it was better than Arm C. Because this study was still blinded at the time of the presentation, investigators didn’t know which regimen constituted which arm. The probability that response favored GD, however, was low.

The investigators observed no surprising safety findings. Eighty-five percent of all patients experienced at least 1 adverse event. Most frequent grade 3‐5 events consisted of pneumonitis (50%, 60%), neutropenic fever (17%, 25%), and diarrhea (0, 12%) in GD and the combined 3 arms, respectively. Grade 3 events in the GD arm were lower than in the other 3 arms combined. There was 1 toxic death attributed to neutropenic sepsis in 1 of the 3 blinded arms.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) for all patients was approximately 5 months. Bayesian analysis suggested there was a low probability that GD was more effective than the other 3 arms: a 22% chance that GD was better than Arm A, a 3% chance that it was better than Arm B, and a 7% chance that it was better than Arm C. Bayesian analysis also suggested there was a probability that OS favored GD. Because the trial directs only the first 4 or 6 cycles of treatment and the patients receive more treatment after trial-directed therapy, investigators were not fully able to interpret this.

Data suggested GD is a less effective regimen than the other 3 regimens both by objective response rate and PFS, so GD has been dropped from the study. Investigators already had more than 75 evaluable patients in each of the 3 arms for the second interim analysis to take place. In a discussion following the presentation, Jayesh Desai, FRACP, of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia, called this study a potentially practice-changing trial at this early stage, noting that the GD combination will be de-prioritized in practice based on these results.

SOURCE: McCabe MG, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11007)

The rEECur trial is sponsored by the University of Birmingham (UK) and received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme under a grant agreement.

Dr. McCabe disclosed no conflicts of interest. Other authors disclosed consulting, advisory roles, or research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Lilly (gemcitabine) and Pfizer (irinotecan). Dr. Desai disclosed a consulting/advisory role and institutional research funding from Lilly.

Abemaciclib Meets Primary Endpoint in Phase 2 Trial of DDLS

The newer and more potent CDK4 inhibitor, abemaciclib, met its primary endpoint in the investigator-initiated, single-center, single-arm, phase 2 trial in patients with advanced progressive dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLS). Twenty-two patients (76%) achieved progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 weeks for a median PFS of 30 weeks. A subset of patients experienced prolonged clinical benefit, remaining on study with stable disease for over 900 days. The study (NCT02846987) was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and Mark A. Dickson, MD, presented the results at ASCO.

Of three agents in the clinic with the potential to target CDK4 and CDK6—palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib— abemaciclib is more selective for CDK4 than CDK6. CDK4 amplification occurs in more than 90% of well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Abemaciclib also has a different side effect profile, with less hematologic toxicity than the other 2 agents. The current study was considered positive if 15 patients or more of a 30-patient sample size were progression- free at 12 weeks.

Results

Thirty patients, 29 evaluable, with metastatic or recurrent DDLS were enrolled and treated with abemaciclib 200 mg orally twice daily between August 2016 and October 2018. Data cutoff for the presentation was the first week of May 2019. Patients were a median of 62 years, 60% were male, and half had no prior systemic treatment. Prior systemic treatments for those previously treated included doxorubicin, olaratumab, gemcitabine, docetaxel, ifosfamide, eribulin, and trabectedin. For 87%, the primary tumor was in their abdomen or retroperitoneum.

Toxicity was as expected with this class of agent, according to the investigators. The most common grades 2 and 3 toxicities, respectively, possibly related to the study drug, occurring in more than 1 patient included anemia (70%, 37%), thrombocytopenia (13%, 13%), neutropenia (43%, 17%), and lymphocyte count decreased (23%, 23%). Very few of these adverse events were grade 4—none for anemia, and 3% each for thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and lymphocyte count decreased. Diarrhea of grades 2 and 3 occurred in 27% and 7% of patients, respectively, and was managed well with loperamide.

In addition to reaching the primary endpoint of 15 patients or more achieving PFS at 12 weeks, 1 patient had a confirmed partial response (PR) and another an unconfirmed PR. At data cutoff, 11 patients remained on study with stable disease or PR. The investigators conducted correlative studies that indicated all patients had CDK4 and MDM2 amplification with no loss of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. They observed an inverse correlation between CDK4 amplification and PFS—the higher the level of CDK4 amplification, the shorter the PFS. They also found additional genomic alterations, including JUN, GLI1, ARID1A, TERT, and ATRX. TERT amplification was also associated with shorter PFS. Based on these findings, the investigators believe a phase 3 study of abemaciclib in DDLS is warranted.

Winette van der Graaf, MD, PhD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, in the discussion following the presentation, concurred that it is certainly time for a multicenter phase 3 study of CDK4 inhibitors in DDLS, and a strong international collaboration is key to conducting such studies, particularly in rare cancers. On a critical note, Dr. van der Graaf expressed concern that no patient-reported outcomes were measured after 120 patients, including those in previous studies, were treated on palbociclib and abemaciclib. Given that the toxicities of the CDK4 inhibitors are quite different, she recommended including patient-reported outcomes in future studies using validated health-related quality-of-life instruments.

SOURCE: Dickson MA, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11004)

The study was sponsored by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, with the study collaborator, Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. Dickson disclosed research funding from Lilly, the company that provided the study drug. Dr. van der Graaf had no relevant relationships to disclose. Abstract coauthors had consulting/advisory roles or research funding from various companies, including Lilly.

nab-Sirolimus Provides Benefits in Advanced Malignant PEComa

In a prospective phase 2 study of nab-sirolimus in advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa), the mTOR inhibitor achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 42% with an acceptable safety profile, despite using relatively high doses of nab-sirolimus compared to other mTOR inhibitors. Activation of the mTOR pathway is common in PEComa, and earlier case reports had indicated substantial clinical benefit with mTOR inhibitor treatment. nab-Sirolimus (ABI-009) is a novel intravenous mTOR inhibitor consisting of nanoparticles of albumin-bound sirolimus. It has significantly higher anti-tumor activity than oral mTOR inhibitors and greater mTOR target suppression at an equal dose. Andrew J. Wagner, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, presented the findings of AMPECT (NCT02494570)—Advanced Malignant PEComa Trial—at ASCO.

Investigators enrolled 34 patients 18 years or older with histologically confirmed malignant PEComa. Patients could not have had prior mTOR inhibitors. They received infusions of 100 mg/m2 nab-sirolimus on days 1 and 8 every 21 days until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients were a median age of 60 years and 44% were 65 or older; 82% were women, which is typical of the disease. Most patients (88%) had no prior systemic therapy for advanced PEComa.

Results

The drug was well tolerated, with toxicities similar to those of oral mTOR inhibitors. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurring in 25% or more of patients were mostly grade 1 or 2 toxicities. Hematologic TRAEs included anemia (47%) and thrombocytopenia (32%) of any grade. Nonhematologic events of any grade included stomatitis/ mucositis (74%), dermatitis/rash (65%), fatigue (59%), nausea (47%), and diarrhea (38%), among others. A few grade 3 events occurred on study, most notably stomatitis/mucositis (18%). Severe adverse events (SAEs) were also uncommon, occurring in 7 of 34 patients (21%). Pneumonitis is common in orally administered mTOR inhibitors; 6 patients (18%) treated with nab-sirolimus had grade 1 or 2 pneumonitis.

Of the 31 evaluable patients, 13 (42%) had an objective response, all of which were partial responses (PR). Eleven (35%) had stable disease and 7 (23%) had progressive disease. The disease control rate, consisting of PR and stable disease, was 77%. The median duration of response had not been reached as of the data cutoff on May 10, 2019. At that time, it was 6.2 months (range, 1.5 to 27.7+). The median time to response was 1.4 months and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 8.4 months. The PFS rate at 6 months was 61%. Three patients had received treatment for over a year and another 3 patients for more than 2 years.

Correlation with biomarkers

Of the 25 patients who had tissue suitable for next-generation sequencing, 9 had TSC2 mutations, 5 had TSC1 mutations, and 11 had neither mutation. Strikingly, 9 of 9 patients with TSC2 mutations developed a PR, while only 1 with a TSC1 mutation responded. One patient with no TSC1/2 mutation also responded and 2 patients with unknown mutational status responded. The investigators also analyzed pS6 status by immunohistochemistry—pS6 is a marker of mTOR hyperactivity. Twenty- five patient samples were available for analysis. Eight of 8 patients who were negative for pS6 staining did not have a response, while 10 of 17 (59%) who were pS6-positive had a PR.

In the discussion that followed, Winette van der Graaf, MD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, noted that this study showed that biomarkers can be used for patient selection, although TSC2 mutations are not uniquely linked with response. She indicated a comparator with sirolimus would have been of great interest.

SOURCE: Wagner AJ, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11005).

The study was sponsored by Aadi Bioscience, Inc., and funded in part by a grant from the FDA Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD).

Disclosures relevant to this presentation include contininstitutional research funding from Aadi Bioscience for Dr. Wagner and a few other abstract coauthors. Several coauthors are employed by Aadi Bioscience and have stock or other ownership interests. Dr. van der Graaf had nothing to disclose.

Cabozantinib Achieves Disease Control in GIST

The phase 2 EORTC 1317 trial, known as CaboGIST (NCT02216578), met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 weeks in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) cabozantinib. Twenty-four (58.5%) of the 41 patients in the primary study population, and 30 (60%) of the entire 50-patient population, were progression-free at 12 weeks. The study needed 21 patients to be progression- free for cabozantinib to warrant further exploration in GIST patients.

Cabozantinib is a multitargeted TKI inhibiting KIT, MET, AXL, and VEGFR2, which are potentially relevant targets in GIST. In patient-derived xenografts of GIST, cabozantinib demonstrated activity in imatinib-sensitive and -resistant models and inhibited tumor growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis. Additional preclinical experience suggested that cabozantinib could potentially be used as a potent MET inhibitor, overcoming upregulation of MET signaling that occurs with imatinib treatment of GIST, known as the kinase switch.

This investigator-initiated study had as its primary objective assessment of the safety and activity of cabozantinib in patients with metastatic GIST who had progressed on imatinib and sunitinib. The patients could not have been exposed to other KIT- or PDGFR-directed TKIs, such as regorafenib. Secondary objectives included the assessment of cabozantinib in different mutational subtypes of GIST. Patients received cabozantinib tablets once daily until they experienced no further clinical benefit or became intolerant to the drug or chose to discontinue therapy. Fifty patients started treatment between February 2017 and August 2018. All were evaluable for the primary endpoint, and one-third of patients contininstitutional cabozantinib treatment as of the database cutoff in January 2019.

Results

Patients were a median age of 63 years. Virtually all patients (92%) had prior surgery and only 8% had prior radiotherapy. The daily cabozantinib dose was a median 47.2 mg and duration of treatment was a median 20.4 weeks. No patient discontinued treatment due to toxicity, but 88% discontinued due to disease progression.

Safety signals were the same as for other indications in which cabozantinib is used. Almost all patients (94%) had at least 1 treatment-related adverse event of grades 1‐4, including diarrhea (74%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (58%), fatigue (46%), and hypertension (46%), which are typical of treatment with cabozantinib. Hematologic toxicities in this trial were clinically irrelevant, according to the investigators, consisting of small numbers of grades 2‐3 anemia, lymphopenia, white blood cell count abnormality, and neutropenia. Biochemical abnormalities included grades 3 and 4 hypophosphatemia, increased grades 3 and 4 gamma-glutamyl transferase, grade 3 hyponatremia, and grade 3 hypokalemia, in 8% or more of patients.

Overall survival was a median 14.4 months, with 16 patients still on treatment at the time of data cutoff. Twenty- four patients were progression-free at week 12, satisfying the study decision rule for clinical benefit. Median duration of PFS was 6.0 months. Seven patients (14%) achieved a confirmed partial response (PR) and 33 (66%) achieved stable disease (SD). Nine patients had progressive disease as their best response, 3 of whom had some clinical benefit. Forty patients (80%) experienced a clinical benefit of disease control (PR + SD).

An analysis of the relationship of genotype, duration, and RECIST response showed objective responses in patients with primary exon 11 mutations, with exon 9 mutations, and with exon 17 mutations, and in 2 patients without any known mutational information at the time of the presentation. Patients with stable disease were spread across all mutational subsets in the trial. The investigators suggested the definitive role of MET and AXL inhibition in GIST be assessed further in future clinical trials.

SOURCE: Schöffski P, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11006).

The study was sponsored by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC).

Presenting author, Patrick Schöffski, MD, of KU Leuven and Leuven Cancer Institute in Belgium, disclosed institutional relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies for consulting and research funding, including research funding from Exelixis, the developer of cabozantinib. No other abstract coauthor disclosed a relationship with Exelixis.

Larotectinib Effective in TRK Fusion Cancers

Pediatric patients with tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) fusions involving NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 genes had a high response rate with durable responses and a favorable safety profile when treated with larotrectinib, according to a presentation at ASCO. In this pediatric subset of children and adolescents from the SCOUT and NAVIGATE studies, the overall response rate (ORR) was 94%, with a 35% complete response (CR), 59% partial response (PR), and 6% stable disease as of the data cutoff at the end of July 2018.

TRK fusion cancer is a rare malignancy seen in a wide variety of adult and childhood tumor types. Among pediatric malignancies, infantile fibrosarcoma and congenital mesoblastic nephroma are rare, but have high NTRK gene fusion frequency. Other sarcomas and pediatric high-grade gliomas, for example, are less rare but have low NTRK gene fusion frequency. Larotrectinib, a first-in-class and the only selective TRK inhibitor, has high potency against the 3 NTRK genes that encode the neurotrophin receptors. It is highly selective and has limited inhibition of the other kinases. The US Food and Drug Administration approved larotrectinib for the treatment of patients with solid tumors harboring NTRK fusions. Cornelis Martinus van Tilburg, MD, of the Hopp Children’s Cancer Center, Heidelberg University Hospital, and German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, presented the findings.

Investigators enrolled 38 children and adolescents younger than 18 years from the SCOUT (NCT02637687) and NAVIGATE (NCT02576431) studies of larotrectinib who had non-central nervous system (CNS) TRK fusion cancers. Not all patients had the recommended phase 2 dose, Dr. van Tilburg pointed out, but most did. Hence, 29 of the 38 patients received the 100 mg/m2 twice-daily, phase 2 dose until progression, withdrawal, or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients were young, with a median age of 2.3 years (range, 0.1 to 14.0 years). Almost two-thirds (61%) had prior surgery, 11% had prior radiotherapy, and 68% had prior systemic therapy. For 12 patients, larotrectinib was their first systemic therapy. The predominant tumor types were infantile fibrosarcoma (47%) and other soft tissue sarcoma (42%). And 47% of patients had NTRK3 fusions with ETV6, most of which were infantile fibrosarcoma.

Efficacy

Thirty-four patients were evaluable, and 32 had a reduction in tumor size, for an ORR of 94%, CR of 35%, and PR of 59%. Two patients with infantile fibrosarcoma had pathologic CRs—after treatment, no fibroid tissue in the tumors could be found. Median time to response was 1.8 months, median duration of treatment was 10.24 months, and 33 of 38 patients (87%) remained on treatment or underwent surgery with curative intent. As of the data cutoff of July 30, 2018, the secondary endpoints were not yet reached. However, 84% of responders were estimated to have a response duration of a year or more, and progression-free and overall survival looked very promising, according to Dr. van Tilburg.

Adverse events were primarily grades 1 and 2. The grades 3 and 4 treatment-related adverse events were quite few and consisted of increased alanine aminotransferase, decreased neutrophil count, and nausea. Longer follow-up of the patient safety profile is required, particularly since NTRK has multiple roles in neurodevelopment. The investigators recommended that routine testing for NTRK gene fusions in pediatric patients with cancer be conducted in appropriate clinical contexts.

In a discussion after the presentation, Daniel Alexander Morgenstern, MB BChir, PhD, of Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK, said that in many ways, the NTRK inhibitors have become the new poster child for precision oncology in pediatrics because of “these really spectacular results” with larotrectinib [and entrectinib]. One of the questions he raised regarding larotrectinib was the issue of CNS penetration, since patients with CNS cancer were not enrolled in the trial and preclinical data suggest limited CNS penetration for larotrectinib.

SOURCE: van Tilburg CM, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 10010).

The studies were funded by Loxo Oncology, Inc., and Bayer AG.

Disclosures relevant to this presentation include consulting or advisory roles for Bayer for Drs. van Tilburg and Morgenstern. A few coauthors also had consulting/advisory roles or research funding from various companies, including Loxo and Bayer.

Behind Olaratumab's Phase 3 Disappointment

ANNOUNCE, the phase 3 trial designed to confirm the clinical benefit of olaratumab in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (STS), failed to meet its primary endpoint of overall survival (OS) in all STS histologies and the leiomyosarcoma population. The previous phase 1b/2 signal-finding study of olaratumab had achieved an unprecedented improvement in OS, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) awarded olaratumab accelerated approval in October 2016. By December 2018, olaratumab received additional accelerated, conditional, and full approvals in more than 40 countries worldwide. William D. Tap, MD, chief of the Sarcoma Medical Oncology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, presented the phase 3 results and provided some explanations for the findings during the plenary session at ASCO.

ANNOUNCE (NCT02451943), which was designed and enrolled prior to olaratumab receiving accelerated approval, opened in September 2015 and completed accrual 10 months later in July 2016. Investigators randomized and treated 509 patients with advanced STS not amenable to curative therapy, 258 patients in the olaratumab-doxorubicin arm and 251 in the placebo-doxorubicin arm. Most patients (46%) had leiomyosarcoma, followed by liposarcoma (18%), pleomorphic sarcoma (13%), and 24% of the patient population had 26 unique histologies. Three-quarters of the patients had no prior systemic therapy.

Results

As of the data cutoff on December 5, 2018, there were no survival differences in the intention-to-treat population, in the total STS population nor in the leiomyosarcoma subpopulation, with olaratumab-doxorubicin compared to placebo-doxorubicin. For the total STS population, median OS with olaratumab- doxorubicin was 20.4 months and with placebo-doxorubicin 19.7 months. “This is the highest survival rate described to date in any phase 3 sarcoma study,” Dr. Tap said. “It is of particular interest as ANNOUNCE did not mandate treatment in the first line.” In the leiomyosarcoma population, median OS was 21.6 months with olaratumab and 21.9 months with placebo. The secondary endpoints of progression-free survival (PFS), overall response rate, and disease control rate did not favor olaratumab either.

Investigators are examining the relationship between PDGFRα expression and OS in ANNOUNCE. PDGFRα-positive tumors tended to do worse with olaratumab than PDGFRα-negative tumors. The investigators noticed a 6-month difference in OS between these populations favoring PDGFRα-negative tumors. Additional biomarker analyses are ongoing.

A large and concerted effort is underway, Dr. Tap said, to understand the results of the ANNOUNCE study alone and in context with the phase 1b/2 study. “There are no noted discrepancies in study conduct or data integrity which could explain these findings or the differences between the two studies.”

Possible explanations

The designs of the phase 1b/2 and phase 3 studies had some important differences. The phase 1b/2 study was a small, open-label, US-centric study (10 sites) that did not include a placebo or subtype- specified analyses. Its primary endpoint was PFS, it did not have a loading dose of olaratumab, and it specified the timing of dexrazoxane administration after 300 mg/m2 of doxorubicin.

ANNOUNCE, on the other hand, was a large (n=509), international (110 study sites), double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that had outcomes evaluated in STS and leiomyosarcoma. Its primary endpoint was OS, it had a loading dose of olaratumab of 20 mg/kg, and there was no restriction as to the timing of dexrazoxane administration.

Dr. Tap pointed out that in ANNOUNCE it was difficult to predict or control for factors that may have had an unanticipated influence on outcomes, such as albumin levels as a surrogate for disease burden and behavior of PDGFRα status. It is possible, he said, that olaratumab has no activity in STS and that the phase 1b/2 results were due to, among other things, the small sample size, numerous represented histologies with disparate clinical behavior, and the effect of subtype-specific therapies on overall survival, given subsequently or even by chance. On the other hand, it is also possible, he said, that olaratumab has some activity in STS, with outcomes being affected by the heterogeneity of the study populations, differences in trial design, and the performance of the ANNOUNCE control arm. Whatever the case, he said, accelerated approval allowed patients to have access to a potentially life-prolonging drug with little added toxicity.

Discussion

In the expert discussion following the presentation, Jaap Verweij, MD, PhD, of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, congratulated the investigators for performing the study at an unprecedented pace. He commented that lumping STS subtypes together is problematic, as different histological subtypes behave as though they are different diseases. Small numbers of each tumor subtype and subtypes with slow tumor growth can impact trial outcomes. In the phase 1b/2 and phase 3 trials, 26 different subtypes were represented in each study. Dr. Verweij pointed out this could have made a big difference in the phase 1b/2 study, in which there were only 66 patients in each arm.

It is striking to note, he said, that without exception, phase 2 randomized studies in STS involving doxorubicin consistently overestimated and wrongly predicted PFS in the subsequent phase 3 studies. And the situation is similar for OS. The results of the ANNOUNCE study are no exception, he added. “Taken together, these studies indicate that phase 2 studies in soft tissue sarcomas, certainly those involving additions of drugs to doxorubicin, even if randomized, should be interpreted with great caution,” he said.

SOURCE: Tap WD, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr LBA3)

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. Tap reported research funding from Lilly and Dr. Verweij had nothing to report related to this study. Abstract coauthors disclosed numerous financial relationships, including consulting/advisory roles and/or research funding from Lilly, and several were employed by Lilly.

Addition of Temozolomide May Improve Outcomes in RMS

Investigators from the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG) found that the addition of temozolomide (T) to vincristine and irinotecan (VI) may improve outcomes in adults and children with relapsed or refractory rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). Principal investigator of the study, Anne Sophie Defachelles, MD, pediatric oncologist at the Centre Oscar Lambret in Lille, France, presented the results on behalf of the EpSSG.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of VI and VIT regimens, defined as objective response (OR)—complete response (CR) plus partial response (PR)—after 2 cycles. Secondary objectives were progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety in each arm, and the relative treatment effect of VIT compared to VI in terms of OR, survival, and safety.

The international, randomized (1:1), open-label, phase 2 trial (VIT-0910; NCT01355445) was conducted at 37 centers in 5 countries. Patients ages 6 months to 50 years with RMS were eligible. They could not have had prior irinotecan or temozolomide. A 2015 protocol amendment limited enrollment to patients at relapse and increased the enrollment goal by 40 patients. After the 2015 amendment, patients with refractory disease were no longer eligible.

From January 2012 to April 2018, investigators enrolled 120 patients, 60 on each arm. Two patients in the VI arm were not treated. Patients were a median age of 10.5 years in the VI arm and 12 years in the VIT arm, 92% (VI) and 87% (VIT) had relapsed disease, 8% (VI) and 13% (VIT) had refractory disease, and 55% (VI) and 68% (VIT) had metastatic disease at study entry.

Results

Patients achieved an OR rate of 44% (VIT) and 31% (VI) for the whole population, one-sided P value <.0001. The adjusted odds ratio for the whole population was 0.50, P=.09. PFS was 4.7 months (VIT) and 3.2 months (VI), “a nearly significant reduction in the risk of progression,” Dr. Defachelles noted. Median OS was 15.0 months (VIT) and 10.3 months (VI), which amounted to “a large and significant reduction in the risk of death,” she said. The adjusted hazard ratio was 0.55, P=.006.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher were more frequent in the VIT arm, with hematologic toxicity the most frequent (81% for VIT, 59% for VI), followed by gastrointestinal adverse events. “VIT was significantly more toxic than VI,” Dr. Defachelles observed, “but the toxicity was manageable.”

“VIT is now the standard treatment in Europe for relapsed rhabdomyosarcoma and will be the control arm in the multiarm, multistage RMS study for relapsed patients,” she said.

In a discussion following the presentation, Lars M. Wagner, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, pointed out that the study was not powered for the PFS and OS assessments. These were secondary objectives that should be considered exploratory. Therefore, he said, the outcome data is not conclusive. The role of temozolomide in RMS is also unclear, given recent negative results in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic RMS (Malempati et al, Cancer 2019). And he said it’s uncertain how these results apply to patients who received irinotecan upfront for RMS.

SOURCE: Defachelles AS, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 10000)

The study was sponsored by Centre Oscar Lambret and SFCE (Société Française de Lutte contre les Cancers et Lucémies de l’Enfant et de l’Adolescent) served as collaborator.

Drs. Defachelles and Wagner had no relationships to disclose. A few coauthors had advisory/consulting or speaker roles for various commercial interests, including two for Merck (temozolomide).

Pazopanib Increases Pathologic Necrosis Rates in STS

Pazopanib added to a regimen of preoperative chemoradiation in non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma (NRSTS) significantly increased the rate of near-complete pathologic response in both children and adults with intermediate or high-risk disease. Pazopanib, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, works in multiple signaling pathways involved in tumorigenesis— VEGFR-1, -2, -3, PDGFRα/β, and c-kit. A phase 3 study demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced STS patients and was the basis for its approval in the US and elsewhere for treatment of this patient population. Preclinical data suggest synergy between pazopanib and cytotoxic chemotherapy, forming the rationale for the current trial with neoadjuvant pazopanib added to chemoradiation.

According to the investigators, the trial (ARST1321) is the first ever collaborative study codeveloped, written, and conducted by pediatric (Children’s Oncology Group) and adult (NRG Oncology) cancer cooperative groups (NCT02180867). Aaron R. Weiss, MD, of the Maine Medical Center in Portland and study cochair, presented the data for the chemotherapy arms at ASCO. The primary objectives of the study were to determine the feasibility of preoperative chemoradiation with or without pazopanib and to compare the rates of complete pathologic response in patients receiving radiation or chemoradiation with or without pazopanib. Pathologic necrosis rates of 90% or better have been found to be predictive of outcome in STS.

Patients with metastatic or non-metastatic NRSTS were eligible to enroll if they had initially unresectable extremity or trunk tumors with the expectation that they would be resectable after therapy. Patients had to be 2 years or older— there was no upper age limit—and had to be able to swallow a tablet whole. The dose-finding phase of the study determined the pediatric dose to be 350 mg/m2 and the adult dose to be 600 mg/m2, both taken orally and once daily. Patients in the chemotherapy cohort were then randomized to receive chemotherapy—ifosfamide and doxorubicin—with or without pazopanib. At 4 weeks, patients in both arms received preoperative radiotherapy (45 Gy in 25 fractions), and at week 13, surgery of the primary site if they did not have progressive disease. After surgery, patients received continuation therapy with or without pazopanib according to their randomization arm. Upon completion and recovery from the continuation therapy, patients could receive surgery/radiotherapy of their metastatic sites.

Results

As of the June 30, 2018, cutoff, 81 patients were enrolled on the chemotherapy arms: 42 in the pazopanib plus chemoradiation arm and 39 in the chemoradiation-only arm. Sixty-one percent of all patients were 18 years or older, and the median age was 20.3 years. Most patients (73%) did not have metastatic disease, and the major histologies represented were synovial sarcoma (49%) and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (25%).

At week 13, patients in the pazopanib arm showed significant improvement, with 14 (58%) of those evaluated having pathologic necrosis of at least 90%, compared with 4 (22%) in the chemoradiation-only arm (P=.02). The study was closed to further accrual.

Eighteen patients were not evaluable for pathologic response and 21 were pending pathologic evaluation at week 13. Radiographic response rates were not statistically significant on either arm. No complete responses (CR) were achieved in the pazopanib arm, but 14 patients (52%) achieved a partial response (PR) and 12 (44%) had stable disease (SD). In the chemoradiation-only arm, 2 patients (8%) achieved a CR, 12 (50%) a PR, and 8 (33%) SD. Fifteen patients in each arm were not evaluated for radiographic response.

The pazopanib arm experienced more febrile neutropenia and myelotoxicity during induction and continuation phases than the chemoradiation-only arm. In general, investigators indicated pazopanib combined with chemoradiation was well tolerated and no unexpected toxicities arose during the trial.

In the post-presentation discussion, Dr. Raphael E. Pollock, MD, PhD, of The Ohio State University, called it a tremendous challenge to interdigitate primary local therapies in systemic approaches, particularly in the neoadjuvant context. He pointed out that in an earlier study, a 95% to 100% necrosis level was needed to achieve a significant positive impact on outcomes and perhaps a subsequent prospective trial could determine the best level. He questioned whether the availability of only 60% of patient responses could affect the conclusions and whether the high number of toxicities (73.8% grade 3/4 with pazopanib) might be too high to consider the treatment for most patients, given the intensity of the regimen.

SOURCE: Weiss AR, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11002)

The study was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute.

Drs. Weiss and Pollock had no relationships with commercial interests to disclose. A few investigators disclosed advisory, consulting, or research roles with pharmaceutical companies, including one who received institutional research funding from Novartis (pazopanib).

Gemcitabine Plus Pazopanib a Potential Alternative in STS

In a phase 2 study of gemcitabine with pazopanib (G+P) or gemcitabine with docetaxel (G+D), investigators concluded the combination with pazopanib can be considered an alternative to that with docetaxel in select patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (STS). They reported similar progression-free survival (PFS) and rate of toxicity for the two regimens. Neeta Somaiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, presented the findings of the investigator-initiated effort (NCT01593748) at ASCO.

The objective of the study, conducted at 10 centers across the United States, was to examine the activity of pazopanib when combined with gemcitabine as an alternative to the commonly used gemcitabine plus docetaxel regimen. Pazopanib is a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor with efficacy in non-adipocytic STS. Adult patients with metastatic or locally advanced non-adipocytic STS with ECOG performance of 0 or 1 were eligible. Patients had to have received prior anthracycline exposure unless it was contraindicated. The 1:1 randomization included stratification for pelvic radiation and leiomyosarcoma histology, which was felt to have a higher response rate with the pazopanib regimen.

The investigators enrolled 90 patients, 45 in each arm. Patients were a mean age of 56 years, and there was no difference in age or gender distribution between the arms. Patients with leiomyosarcoma (31% overall) or prior pelvic radiation (11% overall) were similar between the arms. The overall response rate using RECIST 1.1 criteria was partial response (PR) in 8 of 44 evaluable patients (18%) in the G+D arm and 5 of 43 evaluable patients (12%) in the G+P arm. Stable disease (SD) was observed in 21 patients (48%) in the G+D arm and 24 patients (56%) in the G+P arm. This amounted to a clinical benefit rate (PR + SD) of 66% and 68% for the G+D and G+P arms, respectively (Fisher’s exact test, P>.99). The median PFS was 4.1 months on both arms and the difference in median overall survival— 15.9 months in the G+D arm and 12.4 months in the G+P arm—was not statistically significant.

Adverse events (AEs) of grade 3 or higher occurred in 19.9% of patients on G+D and 20.6% on G+P. Serious AEs occurred in 33% (G+D) and 22% (G+P). Dose reductions were necessary in 80% of patients on G+P and doses were held in 93%. Dr. Somaiah explained that this may have been because the starting dose of gemcitabine and pazopanib (1000 mg/m2 of gemcitabine on days 1 and 8 and 800 mg of pazopanib) was “probably higher than what we should have started at.” The rate of doses held was also higher in the pazopanib arm (93%) compared with the docetaxel arm (58%). This was likely because pazopanib was a daily dosing, so if there was a toxicity it was more likely to be held than docetaxel, she observed. Grade 3 or higher toxicities occurring in 5% or more of patients in either arm consisted generally of cytopenias and fatigue. The G+P arm experienced a high amount of neutropenia, most likely because this arm did not receive granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) support, as opposed to the G+D arm.

Dr. Somaiah pointed out that the 12% response rate for the G+P combination is similar to what has been previously presented and higher than single-agent gemcitabine or pazopanib, but not higher than the G+D combination. The PFS of 4.1 months was less than anticipated, she added, but it was similar on both arms. The investigators believe the G+P combination warrants further exploration.

SOURCE: Somaiah N, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11008)

The study was sponsored by the Medical University of South Carolina, with Novartis as collaborator.

Dr. Somaiah disclosed Advisory Board roles for Blueprint, Deciphera, and Bayer. Abstract coauthors disclosed advisory/consulting roles or research funding from various commercial interests, including Novartis (pazopanib) and Pfizer (gemcitabine).

rEECur Trial Finding Optimal Chemotherapy Regimen for Ewing Sarcoma

Interim results of the first and largest randomized trial in patients with refractory or recurrent Ewing sarcoma (ES), the rEECur trial, are guiding the way to finding the optimal chemotherapy regimen to treat the disease. Until now, there has been little prospective evidence and no randomized data to guide treatment choices in relapsed or refractory patients, and hence no real standard of care, according to the presentation at ASCO. Several molecularly targeted therapies are emerging, and they require a standardized chemotherapy backbone against which they can be tested.

The rEECur trial (ISRCTN36453794) is a multi-arm, multistage phase 2/3 “drop-a-loser” randomized trial designed to find the standard of care. The trial compares 4 chemotherapy regimens to each other and drops the least effective one after 50 patients per arm are enrolled and evaluated. The 3 remaining regimens continue until at least 75 patients on each arm are enrolled and evaluated, and then another arm would be dropped. The 2 remaining regimens continue to phase 3 evaluation. Four regimens are being tested at 8 centers in 17 countries: topotecan/ cyclophosphamide (TC), irinotecan/temozolomide (IT), gemcitabine/docetaxel (GD), and ifosfamide (IFOS). The primary objective is to identify the optimal regimen based on a balance between efficacy and toxicity. Martin G. McCabe, MB BChir, PhD, of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, presented the results on behalf of the investigators of the rEECur trial.

Results

Two hundred twenty patients 4 years or older and younger than 50 years with recurrent or refractory histologically confirmed ES of bone or soft tissue were randomized to receive GD (n=72) or TC, IT, or IFOS (n=148). Sixty-two GD patients and 123 TC/IT/IFOS patients were included in the primary outcome analysis. Patients were predominantly male (70%), with a median age of 19 years (range, 4 to 49). About two-thirds (67.3%) were post-pubertal. Most patients (85%) were primary refractory or experienced their first disease recurrence, and 89% had measurable disease.

Investigators assessed the primary outcome of objective response after 4 cycles of therapy and found 11% of patients treated with GD responded compared to 24% in the other 3 arms combined. When they subjected the data to Bayesian analysis, there was a 25% chance that the response rate in the GD arm was better than the response in Arm A, a 2% chance that it was better than Arm B, and a 3% chance that it was better than Arm C. Because this study was still blinded at the time of the presentation, investigators didn’t know which regimen constituted which arm. The probability that response favored GD, however, was low.

The investigators observed no surprising safety findings. Eighty-five percent of all patients experienced at least 1 adverse event. Most frequent grade 3‐5 events consisted of pneumonitis (50%, 60%), neutropenic fever (17%, 25%), and diarrhea (0, 12%) in GD and the combined 3 arms, respectively. Grade 3 events in the GD arm were lower than in the other 3 arms combined. There was 1 toxic death attributed to neutropenic sepsis in 1 of the 3 blinded arms.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) for all patients was approximately 5 months. Bayesian analysis suggested there was a low probability that GD was more effective than the other 3 arms: a 22% chance that GD was better than Arm A, a 3% chance that it was better than Arm B, and a 7% chance that it was better than Arm C. Bayesian analysis also suggested there was a probability that OS favored GD. Because the trial directs only the first 4 or 6 cycles of treatment and the patients receive more treatment after trial-directed therapy, investigators were not fully able to interpret this.

Data suggested GD is a less effective regimen than the other 3 regimens both by objective response rate and PFS, so GD has been dropped from the study. Investigators already had more than 75 evaluable patients in each of the 3 arms for the second interim analysis to take place. In a discussion following the presentation, Jayesh Desai, FRACP, of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia, called this study a potentially practice-changing trial at this early stage, noting that the GD combination will be de-prioritized in practice based on these results.

SOURCE: McCabe MG, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11007)

The rEECur trial is sponsored by the University of Birmingham (UK) and received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme under a grant agreement.

Dr. McCabe disclosed no conflicts of interest. Other authors disclosed consulting, advisory roles, or research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Lilly (gemcitabine) and Pfizer (irinotecan). Dr. Desai disclosed a consulting/advisory role and institutional research funding from Lilly.

Abemaciclib Meets Primary Endpoint in Phase 2 Trial of DDLS

The newer and more potent CDK4 inhibitor, abemaciclib, met its primary endpoint in the investigator-initiated, single-center, single-arm, phase 2 trial in patients with advanced progressive dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLS). Twenty-two patients (76%) achieved progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 weeks for a median PFS of 30 weeks. A subset of patients experienced prolonged clinical benefit, remaining on study with stable disease for over 900 days. The study (NCT02846987) was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and Mark A. Dickson, MD, presented the results at ASCO.

Of three agents in the clinic with the potential to target CDK4 and CDK6—palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib— abemaciclib is more selective for CDK4 than CDK6. CDK4 amplification occurs in more than 90% of well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Abemaciclib also has a different side effect profile, with less hematologic toxicity than the other 2 agents. The current study was considered positive if 15 patients or more of a 30-patient sample size were progression- free at 12 weeks.

Results

Thirty patients, 29 evaluable, with metastatic or recurrent DDLS were enrolled and treated with abemaciclib 200 mg orally twice daily between August 2016 and October 2018. Data cutoff for the presentation was the first week of May 2019. Patients were a median of 62 years, 60% were male, and half had no prior systemic treatment. Prior systemic treatments for those previously treated included doxorubicin, olaratumab, gemcitabine, docetaxel, ifosfamide, eribulin, and trabectedin. For 87%, the primary tumor was in their abdomen or retroperitoneum.

Toxicity was as expected with this class of agent, according to the investigators. The most common grades 2 and 3 toxicities, respectively, possibly related to the study drug, occurring in more than 1 patient included anemia (70%, 37%), thrombocytopenia (13%, 13%), neutropenia (43%, 17%), and lymphocyte count decreased (23%, 23%). Very few of these adverse events were grade 4—none for anemia, and 3% each for thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and lymphocyte count decreased. Diarrhea of grades 2 and 3 occurred in 27% and 7% of patients, respectively, and was managed well with loperamide.

In addition to reaching the primary endpoint of 15 patients or more achieving PFS at 12 weeks, 1 patient had a confirmed partial response (PR) and another an unconfirmed PR. At data cutoff, 11 patients remained on study with stable disease or PR. The investigators conducted correlative studies that indicated all patients had CDK4 and MDM2 amplification with no loss of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. They observed an inverse correlation between CDK4 amplification and PFS—the higher the level of CDK4 amplification, the shorter the PFS. They also found additional genomic alterations, including JUN, GLI1, ARID1A, TERT, and ATRX. TERT amplification was also associated with shorter PFS. Based on these findings, the investigators believe a phase 3 study of abemaciclib in DDLS is warranted.

Winette van der Graaf, MD, PhD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, in the discussion following the presentation, concurred that it is certainly time for a multicenter phase 3 study of CDK4 inhibitors in DDLS, and a strong international collaboration is key to conducting such studies, particularly in rare cancers. On a critical note, Dr. van der Graaf expressed concern that no patient-reported outcomes were measured after 120 patients, including those in previous studies, were treated on palbociclib and abemaciclib. Given that the toxicities of the CDK4 inhibitors are quite different, she recommended including patient-reported outcomes in future studies using validated health-related quality-of-life instruments.

SOURCE: Dickson MA, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11004)

The study was sponsored by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, with the study collaborator, Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. Dickson disclosed research funding from Lilly, the company that provided the study drug. Dr. van der Graaf had no relevant relationships to disclose. Abstract coauthors had consulting/advisory roles or research funding from various companies, including Lilly.

nab-Sirolimus Provides Benefits in Advanced Malignant PEComa

In a prospective phase 2 study of nab-sirolimus in advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa), the mTOR inhibitor achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 42% with an acceptable safety profile, despite using relatively high doses of nab-sirolimus compared to other mTOR inhibitors. Activation of the mTOR pathway is common in PEComa, and earlier case reports had indicated substantial clinical benefit with mTOR inhibitor treatment. nab-Sirolimus (ABI-009) is a novel intravenous mTOR inhibitor consisting of nanoparticles of albumin-bound sirolimus. It has significantly higher anti-tumor activity than oral mTOR inhibitors and greater mTOR target suppression at an equal dose. Andrew J. Wagner, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, presented the findings of AMPECT (NCT02494570)—Advanced Malignant PEComa Trial—at ASCO.

Investigators enrolled 34 patients 18 years or older with histologically confirmed malignant PEComa. Patients could not have had prior mTOR inhibitors. They received infusions of 100 mg/m2 nab-sirolimus on days 1 and 8 every 21 days until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients were a median age of 60 years and 44% were 65 or older; 82% were women, which is typical of the disease. Most patients (88%) had no prior systemic therapy for advanced PEComa.

Results

The drug was well tolerated, with toxicities similar to those of oral mTOR inhibitors. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurring in 25% or more of patients were mostly grade 1 or 2 toxicities. Hematologic TRAEs included anemia (47%) and thrombocytopenia (32%) of any grade. Nonhematologic events of any grade included stomatitis/ mucositis (74%), dermatitis/rash (65%), fatigue (59%), nausea (47%), and diarrhea (38%), among others. A few grade 3 events occurred on study, most notably stomatitis/mucositis (18%). Severe adverse events (SAEs) were also uncommon, occurring in 7 of 34 patients (21%). Pneumonitis is common in orally administered mTOR inhibitors; 6 patients (18%) treated with nab-sirolimus had grade 1 or 2 pneumonitis.

Of the 31 evaluable patients, 13 (42%) had an objective response, all of which were partial responses (PR). Eleven (35%) had stable disease and 7 (23%) had progressive disease. The disease control rate, consisting of PR and stable disease, was 77%. The median duration of response had not been reached as of the data cutoff on May 10, 2019. At that time, it was 6.2 months (range, 1.5 to 27.7+). The median time to response was 1.4 months and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 8.4 months. The PFS rate at 6 months was 61%. Three patients had received treatment for over a year and another 3 patients for more than 2 years.

Correlation with biomarkers

Of the 25 patients who had tissue suitable for next-generation sequencing, 9 had TSC2 mutations, 5 had TSC1 mutations, and 11 had neither mutation. Strikingly, 9 of 9 patients with TSC2 mutations developed a PR, while only 1 with a TSC1 mutation responded. One patient with no TSC1/2 mutation also responded and 2 patients with unknown mutational status responded. The investigators also analyzed pS6 status by immunohistochemistry—pS6 is a marker of mTOR hyperactivity. Twenty- five patient samples were available for analysis. Eight of 8 patients who were negative for pS6 staining did not have a response, while 10 of 17 (59%) who were pS6-positive had a PR.

In the discussion that followed, Winette van der Graaf, MD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, noted that this study showed that biomarkers can be used for patient selection, although TSC2 mutations are not uniquely linked with response. She indicated a comparator with sirolimus would have been of great interest.

SOURCE: Wagner AJ, et al. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11005).

The study was sponsored by Aadi Bioscience, Inc., and funded in part by a grant from the FDA Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD).

Disclosures relevant to this presentation include contininstitutional research funding from Aadi Bioscience for Dr. Wagner and a few other abstract coauthors. Several coauthors are employed by Aadi Bioscience and have stock or other ownership interests. Dr. van der Graaf had nothing to disclose.

Cabozantinib Achieves Disease Control in GIST

The phase 2 EORTC 1317 trial, known as CaboGIST (NCT02216578), met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 weeks in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) cabozantinib. Twenty-four (58.5%) of the 41 patients in the primary study population, and 30 (60%) of the entire 50-patient population, were progression-free at 12 weeks. The study needed 21 patients to be progression- free for cabozantinib to warrant further exploration in GIST patients.

Cabozantinib is a multitargeted TKI inhibiting KIT, MET, AXL, and VEGFR2, which are potentially relevant targets in GIST. In patient-derived xenografts of GIST, cabozantinib demonstrated activity in imatinib-sensitive and -resistant models and inhibited tumor growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis. Additional preclinical experience suggested that cabozantinib could potentially be used as a potent MET inhibitor, overcoming upregulation of MET signaling that occurs with imatinib treatment of GIST, known as the kinase switch.

This investigator-initiated study had as its primary objective assessment of the safety and activity of cabozantinib in patients with metastatic GIST who had progressed on imatinib and sunitinib. The patients could not have been exposed to other KIT- or PDGFR-directed TKIs, such as regorafenib. Secondary objectives included the assessment of cabozantinib in different mutational subtypes of GIST. Patients received cabozantinib tablets once daily until they experienced no further clinical benefit or became intolerant to the drug or chose to discontinue therapy. Fifty patients started treatment between February 2017 and August 2018. All were evaluable for the primary endpoint, and one-third of patients contininstitutional cabozantinib treatment as of the database cutoff in January 2019.

Results

Patients were a median age of 63 years. Virtually all patients (92%) had prior surgery and only 8% had prior radiotherapy. The daily cabozantinib dose was a median 47.2 mg and duration of treatment was a median 20.4 weeks. No patient discontinued treatment due to toxicity, but 88% discontinued due to disease progression.

Safety signals were the same as for other indications in which cabozantinib is used. Almost all patients (94%) had at least 1 treatment-related adverse event of grades 1‐4, including diarrhea (74%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (58%), fatigue (46%), and hypertension (46%), which are typical of treatment with cabozantinib. Hematologic toxicities in this trial were clinically irrelevant, according to the investigators, consisting of small numbers of grades 2‐3 anemia, lymphopenia, white blood cell count abnormality, and neutropenia. Biochemical abnormalities included grades 3 and 4 hypophosphatemia, increased grades 3 and 4 gamma-glutamyl transferase, grade 3 hyponatremia, and grade 3 hypokalemia, in 8% or more of patients.