User login

Obesity Etiology

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Swollen elbow and knee joints

Obesity is a chronic disease affecting more than 20% of adults in the United States. In 2022, prevalence was 20.5% among those aged 18 to 24 and 39.9% among those aged 45 to 54 years. This patient meets criteria for obesity (BMI ≥ 30), and it is likely that her obesity contributed to development of T2D, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and joint edema (as shown in the image).

Patients with obesity are at high risk of developing cardiometabolic disease and osteoarthritis. Obesity is a key driver of T2D and cardiovascular disease development through its influence on insulin and lipid metabolism and proinflammatory changes. Factors associated with obesity that foster arthritis development include the erosive effects of adiponectin and leptin on cartilage and direct inflammation in joint tissues.

It is important for patients with obesity and comorbid T2D and hypertension to receive multidisciplinary care designed to address all aspects of their health and minimize their risk for progression. The primary goal for this patient should be to promote weight loss safely while also improving her glycemic control and blood pressure. For patients with obesity and comorbid T2D, the American Diabetes Association recommends glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; semaglutide or liraglutide) or the dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA tirzepatide. The GLP-1 RA drugs reduce the risk for major cardiovascular events for patients with T2D while also providing substantial reductions in glucose levels without increasing hypoglycemia risk. They are available in higher doses (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly, liraglutide 3.0 mg daily) for patients with obesity. These drugs also have salubrious effects on cardiorenal health and reduce progression of kidney disease. Tirzepatide produced greater reductions in A1c vs semaglutide in patients with T2D in the SURPASS-2 trial. It also has been shown to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in patients with overweight or obesity (without diabetes) in a post hoc analysis of the SURMOUNT-1 trial. Its effect on a broad set of cardiac, renal, and metabolic outcomes is being studied in the ongoing SURMOUNT-MMO trial. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27).

Pharmacologic interventions for osteoarthritis include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib. These may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

In addition, comprehensive care includes lifestyle modifications designed to promote weight loss, reduce sodium, and increase exercise and intake of healthy foods. While maintaining intensive lifestyle modifications can be challenging, achieving weight loss of ≥ 5% can improve cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with obesity and T2D. Greater benefit is seen with greater reductions in body weight. Other interventions include behavioral modification and encouragement of increased physical activity to the extent of the patient's ability. Achieving substantial weight loss also could help relieve stress on the patient's joints, improve physical function, and mitigate osteoarthritis-related pain. The patient also may benefit from nonpharmacologic approaches to joint pain, including hot or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Obesity is a chronic disease affecting more than 20% of adults in the United States. In 2022, prevalence was 20.5% among those aged 18 to 24 and 39.9% among those aged 45 to 54 years. This patient meets criteria for obesity (BMI ≥ 30), and it is likely that her obesity contributed to development of T2D, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and joint edema (as shown in the image).

Patients with obesity are at high risk of developing cardiometabolic disease and osteoarthritis. Obesity is a key driver of T2D and cardiovascular disease development through its influence on insulin and lipid metabolism and proinflammatory changes. Factors associated with obesity that foster arthritis development include the erosive effects of adiponectin and leptin on cartilage and direct inflammation in joint tissues.

It is important for patients with obesity and comorbid T2D and hypertension to receive multidisciplinary care designed to address all aspects of their health and minimize their risk for progression. The primary goal for this patient should be to promote weight loss safely while also improving her glycemic control and blood pressure. For patients with obesity and comorbid T2D, the American Diabetes Association recommends glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; semaglutide or liraglutide) or the dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA tirzepatide. The GLP-1 RA drugs reduce the risk for major cardiovascular events for patients with T2D while also providing substantial reductions in glucose levels without increasing hypoglycemia risk. They are available in higher doses (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly, liraglutide 3.0 mg daily) for patients with obesity. These drugs also have salubrious effects on cardiorenal health and reduce progression of kidney disease. Tirzepatide produced greater reductions in A1c vs semaglutide in patients with T2D in the SURPASS-2 trial. It also has been shown to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in patients with overweight or obesity (without diabetes) in a post hoc analysis of the SURMOUNT-1 trial. Its effect on a broad set of cardiac, renal, and metabolic outcomes is being studied in the ongoing SURMOUNT-MMO trial. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27).

Pharmacologic interventions for osteoarthritis include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib. These may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

In addition, comprehensive care includes lifestyle modifications designed to promote weight loss, reduce sodium, and increase exercise and intake of healthy foods. While maintaining intensive lifestyle modifications can be challenging, achieving weight loss of ≥ 5% can improve cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with obesity and T2D. Greater benefit is seen with greater reductions in body weight. Other interventions include behavioral modification and encouragement of increased physical activity to the extent of the patient's ability. Achieving substantial weight loss also could help relieve stress on the patient's joints, improve physical function, and mitigate osteoarthritis-related pain. The patient also may benefit from nonpharmacologic approaches to joint pain, including hot or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Obesity is a chronic disease affecting more than 20% of adults in the United States. In 2022, prevalence was 20.5% among those aged 18 to 24 and 39.9% among those aged 45 to 54 years. This patient meets criteria for obesity (BMI ≥ 30), and it is likely that her obesity contributed to development of T2D, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and joint edema (as shown in the image).

Patients with obesity are at high risk of developing cardiometabolic disease and osteoarthritis. Obesity is a key driver of T2D and cardiovascular disease development through its influence on insulin and lipid metabolism and proinflammatory changes. Factors associated with obesity that foster arthritis development include the erosive effects of adiponectin and leptin on cartilage and direct inflammation in joint tissues.

It is important for patients with obesity and comorbid T2D and hypertension to receive multidisciplinary care designed to address all aspects of their health and minimize their risk for progression. The primary goal for this patient should be to promote weight loss safely while also improving her glycemic control and blood pressure. For patients with obesity and comorbid T2D, the American Diabetes Association recommends glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; semaglutide or liraglutide) or the dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA tirzepatide. The GLP-1 RA drugs reduce the risk for major cardiovascular events for patients with T2D while also providing substantial reductions in glucose levels without increasing hypoglycemia risk. They are available in higher doses (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly, liraglutide 3.0 mg daily) for patients with obesity. These drugs also have salubrious effects on cardiorenal health and reduce progression of kidney disease. Tirzepatide produced greater reductions in A1c vs semaglutide in patients with T2D in the SURPASS-2 trial. It also has been shown to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in patients with overweight or obesity (without diabetes) in a post hoc analysis of the SURMOUNT-1 trial. Its effect on a broad set of cardiac, renal, and metabolic outcomes is being studied in the ongoing SURMOUNT-MMO trial. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27).

Pharmacologic interventions for osteoarthritis include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib. These may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

In addition, comprehensive care includes lifestyle modifications designed to promote weight loss, reduce sodium, and increase exercise and intake of healthy foods. While maintaining intensive lifestyle modifications can be challenging, achieving weight loss of ≥ 5% can improve cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with obesity and T2D. Greater benefit is seen with greater reductions in body weight. Other interventions include behavioral modification and encouragement of increased physical activity to the extent of the patient's ability. Achieving substantial weight loss also could help relieve stress on the patient's joints, improve physical function, and mitigate osteoarthritis-related pain. The patient also may benefit from nonpharmacologic approaches to joint pain, including hot or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 24-year-old woman presents for swollen and painful elbow and knee joints. The patient is 5 ft 7 in tall and weighs 235 lb (BMI 36.8). The patient says she has been overweight since her preteen years and has never been involved in sports or exercise activities. She has gained a significant amount of weight in the past 2 years since beginning work in an insurance office. She has lived at home with her parents since graduating from college.

Her elbows are tender to the touch; further examination reveals tender joints at her wrists, knees, and hips as well. Extremities are thick because of obesity.

Medical history includes diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) at age 22. In the office, her blood pressure is elevated (150/85 mm Hg), heart rate is 110 beats/min, and respiratory rate is 18 breaths/min. Lab results indicate A1c = 8.5%, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol = 145 mg/dL, and estimated glomerular filtration rate = 90 mL/min/1.73 m2; all other results are within normal range. Her only current medication is metformin 1000 mg daily.

In-office radiography reveals no obvious bone or joint damage.

Weight gain despite dieting

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 28-year-old woman presents with concerns about weight gain despite dieting. She is 5 ft 4 in and weighs 180 lb (BMI 30.9). The patient lives alone and says she often feels isolated and has ongoing anxiety. She states that she has been overweight since her early teen years and had rare episodes of overeating. As an adult, her weight remained relatively stable (BMI ~26) until she began working remotely because of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. She admits to becoming increasingly anxious and worried about food availability and grocery shopping during the early pandemic closures, feelings that have not completely resolved. While working from home, she has had more days where she compulsively overeats, even while trying to diet or use supplements she saw on TV or the internet. She stopped participating in a regular exercise walking group in mid-2020 and has not returned to it.

At presentation, she appears anxious and nervous. Her blood pressure is elevated (140/90 mm Hg), heart rate is 110 beats/min, and respiratory rate is 18 breaths/min. Her results on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder assessment indicate moderate symptoms of anxiety. Lab results indicate A1c = 6.5%, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol = 105 mg/dL, and estimated glomerular filtration rate = 90 mL/min/1.73 m2; all other results are within normal.

Obesity: The Basics

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Knee pain on walking

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 32-year-old woman presents with knee pain on walking and elbow pain. She is 5 ft 6 in tall and weighs 187 lb (BMI 30.2). She was diagnosed with schizophrenia 2 years ago and began treatment with olanzapine at diagnosis; her symptoms currently are controlled, and she has tolerated the medication well.

The patient says that she has been overweight since her teenage years and weighed 170 lb (BMI ~27) at age 30. However, she remained physically active until development of painful joints over the past 18 months. She works remotely full time and lives alone. She describes her long-standing diet as heavy on meat protein and light on vegetables and snacks and says it hasn't changed; she denies binge eating or other disordered eating.

Physical exam reveals tender joints at knees and elbows and central obesity (waist circumference, 42 in). Blood pressure is 135/90 mm Hg. Lab results indicate a fasting glucose level of 115 mg/dL and a triglyceride level of 170 mg/dL. She is negative for rheumatoid factor. Radiography shows premature joint erosion at the knees and elbows.

Obesity and Pregnancy

Dyspnea and mild edema

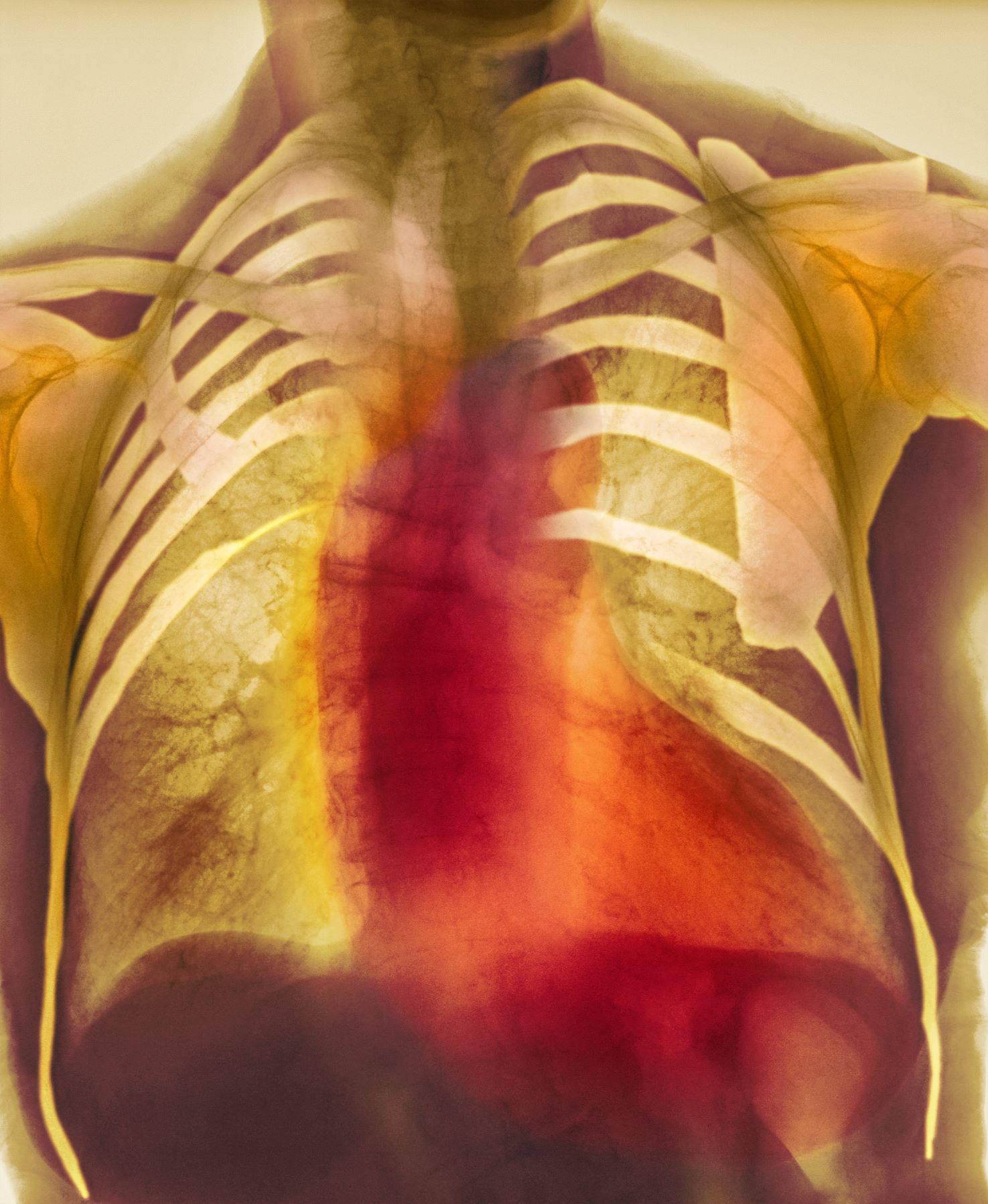

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old patient with obesity presents with dyspnea and mild edema. The patient is 5 ft 9 in, weighs 210 lb (BMI 31), and received an obesity diagnosis 1 year ago with a weight of 220 lb (BMI 32.5) but notes having lived with a BMI ≥ 30 for at least 5 years. Since being diagnosed with obesity, the patient has participated in regular counseling with a clinical nutrition specialist and exercise therapy, reports satisfaction with these, and is happy to have lost 10 lb. The patient presents today for follow-up physical exam and lab workup, with a complaint of increasing dyspnea that has limited participation in exercise therapy over the past 2 months.

On physical exam, the patient appears pale, with shortness of breath and mild edema in the ankles. The heart rhythm is fluttery and the heart rate is elevated at 90 beats/min. Blood pressure is 150/90 mm Hg. Lab results show A1c 6.6% and fasting glucose of 115 mg/dL. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is 101 mg/dL. Thyroid and hematologic findings are within normal parameters. The patient is sent for chest radiography, shown above (colorized).