User login

CASE A 73-year-old woman presents to your clinic with 1 year of gradual-onset left knee pain. The pain is worse at the medial knee and at the beginning and end of the day, with some mild improvement after activity in the morning. The patient has already tried oral acetaminophen, an over-the-counter menthol cream, and a soft elastic knee brace, but these interventions have helped only minimally.

On physical exam, there is no obvious deformity of the knee. There is a bit of small joint effusion without redness or warmth. There is mild tenderness to palpation of the medial joint line. Radiographic findings include osteophytes of the medial and lateral tibial plateaus and medial and lateral femoral condyles with mild joint-space narrowing of the medial compartment, consistent with mild osteoarthritis.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

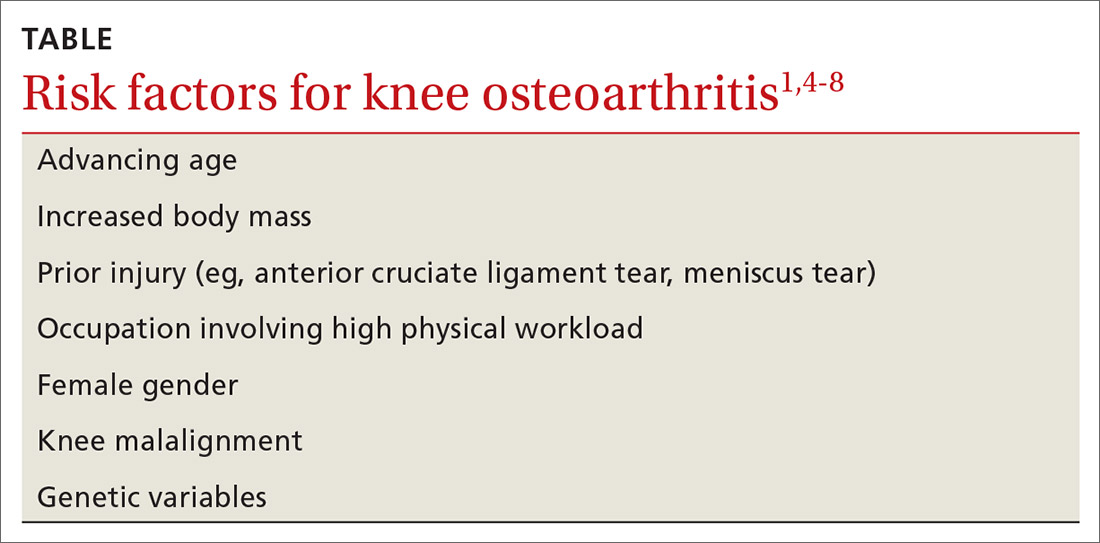

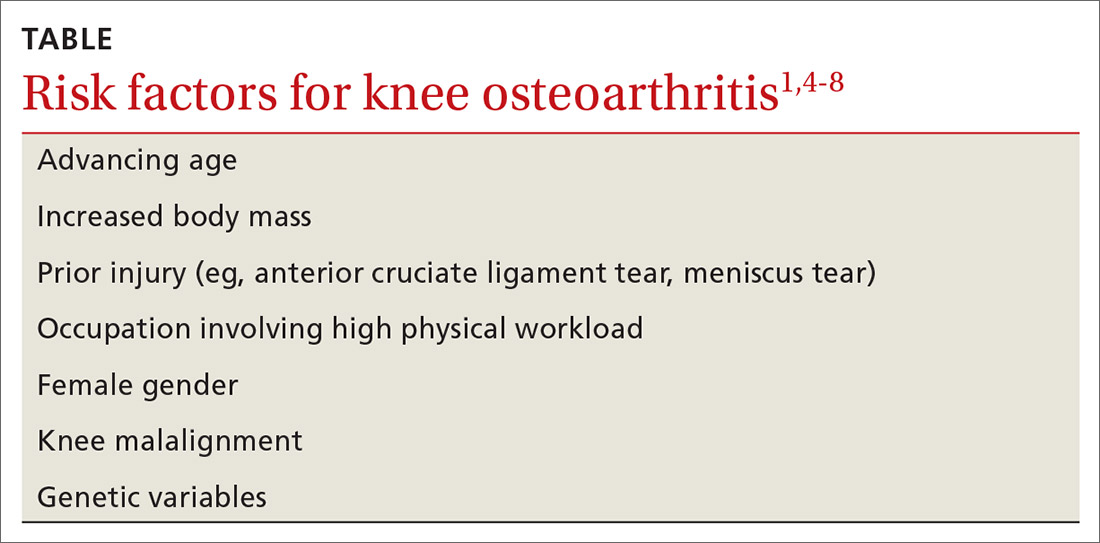

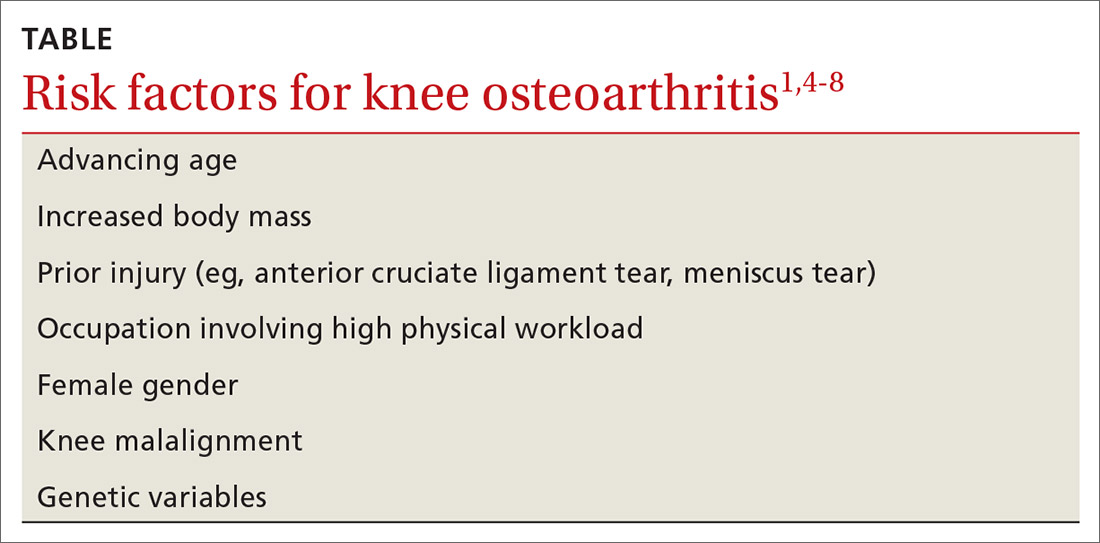

The knee is the most common joint to be affected by osteoarthritis (OA) and accounts for the majority of the disease’s total burden.1 More than 19% of American adults ages ≥ 45 years have knee OA,1,2 and more than half of the people with symptomatic knee OA in the United States are younger than 65 years of age.3 Longer lifespan and increasing rates of obesity are thought to be driving the increasing prevalence of knee OA, although this remains debated.1 Risk factors for knee OA are outlined in TABLE.1,4-8

Diagnosis: Radiographs are helpful, not essential

The diagnosis of knee OA is relatively straightforward. Gradual onset of knee joint pain is present most days, with pain worse after activity and better with rest. Patients are usually middle-aged or older and/or have a distant history of knee joint injury. Other signs, symptoms, and physical exam findings associated with knee OA include: morning stiffness < 30 minutes, crepitus, instability, range-of-motion deficit, varus or valgus deformity, bony exostosis, joint-line tenderness, joint swelling/effusion, and the absence of erythema/warmth.1,9,10

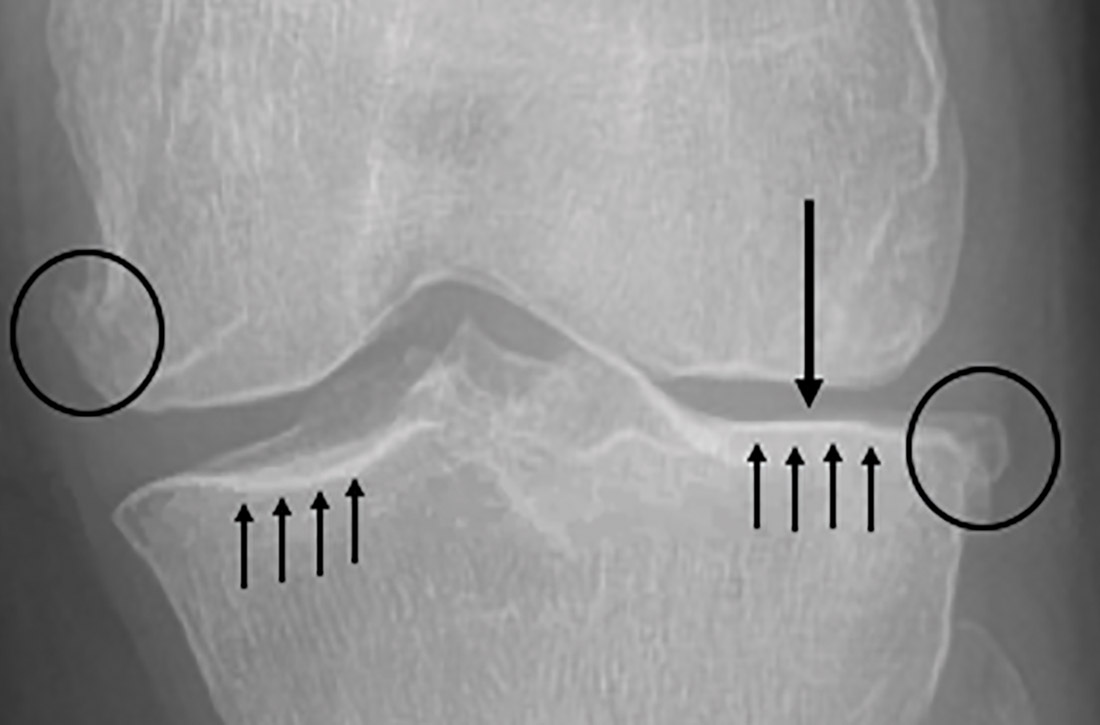

Although radiographs are not necessary to diagnose knee OA, they can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis by assessing the degree and location of OA and ruling out other pathology. Standing, weight-bearing radiographs are particularly helpful for assessing the degree of joint-space narrowing. In addition to joint-space narrowing, radiographic findings indicative of knee OA include marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cysts. (See FIGURE 1.)

Keep in mind that radiographs are less sensitive for early OA, that the degree of OA seen on radiographs does not correlate well with symptoms, and that radiographic evidence of OA is a common incidental finding—especially in elderly individuals.11 Although not routinely utilized for knee OA diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess for earlier stages of the disease and to rule out pathology associated with the soft tissue and cartilage that is not directly associated with OA.

Continue to: Management

Management: Decrease pain, improve function, slow progression

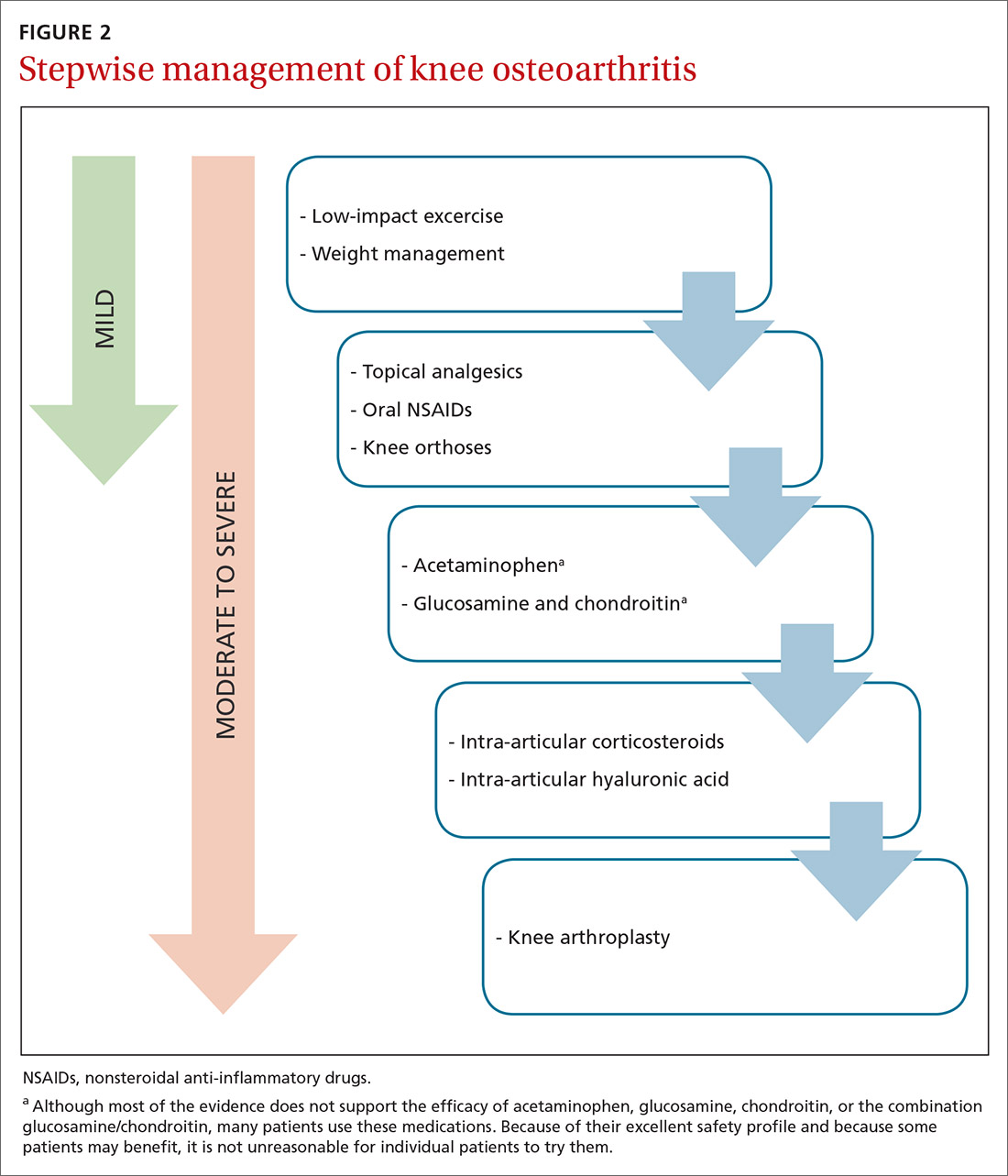

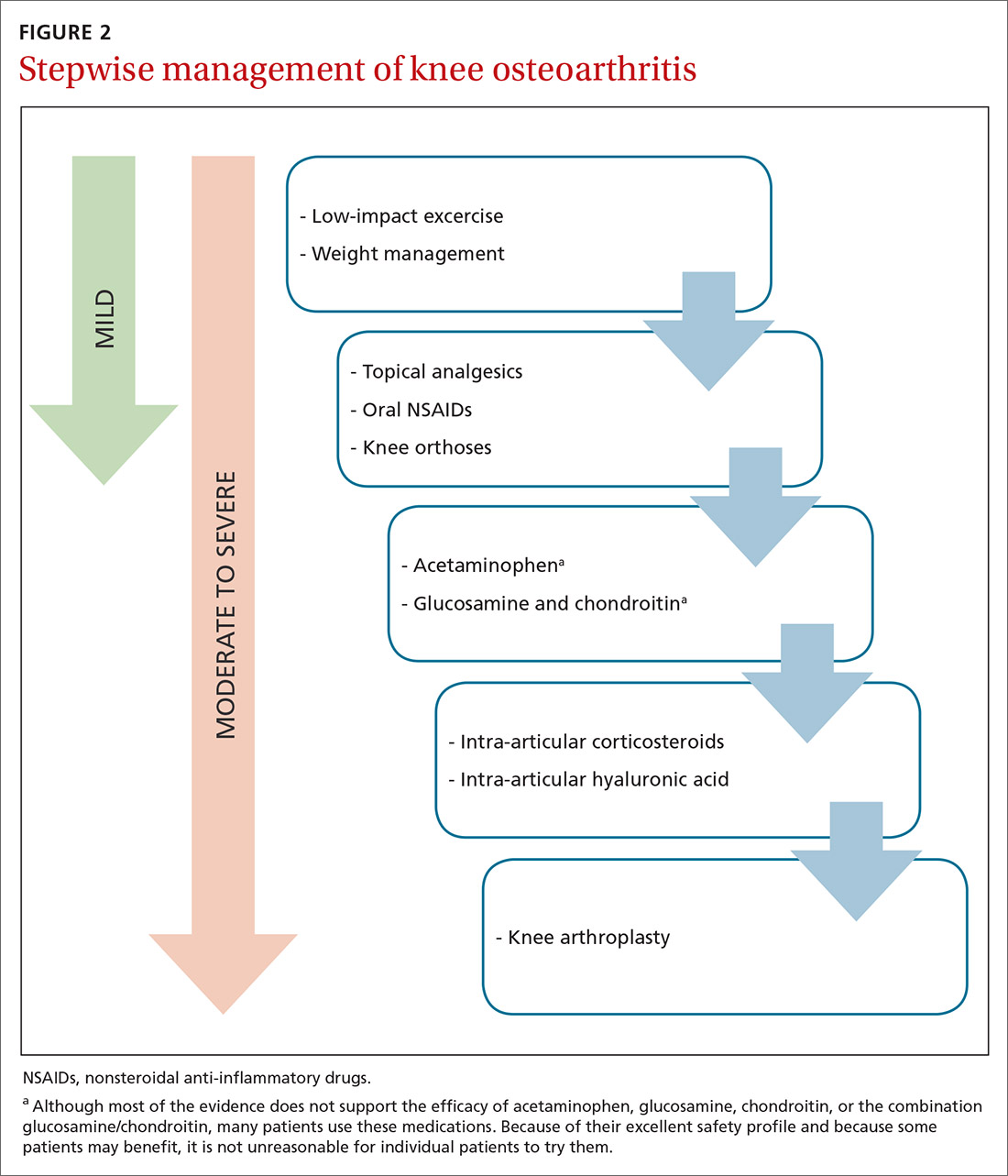

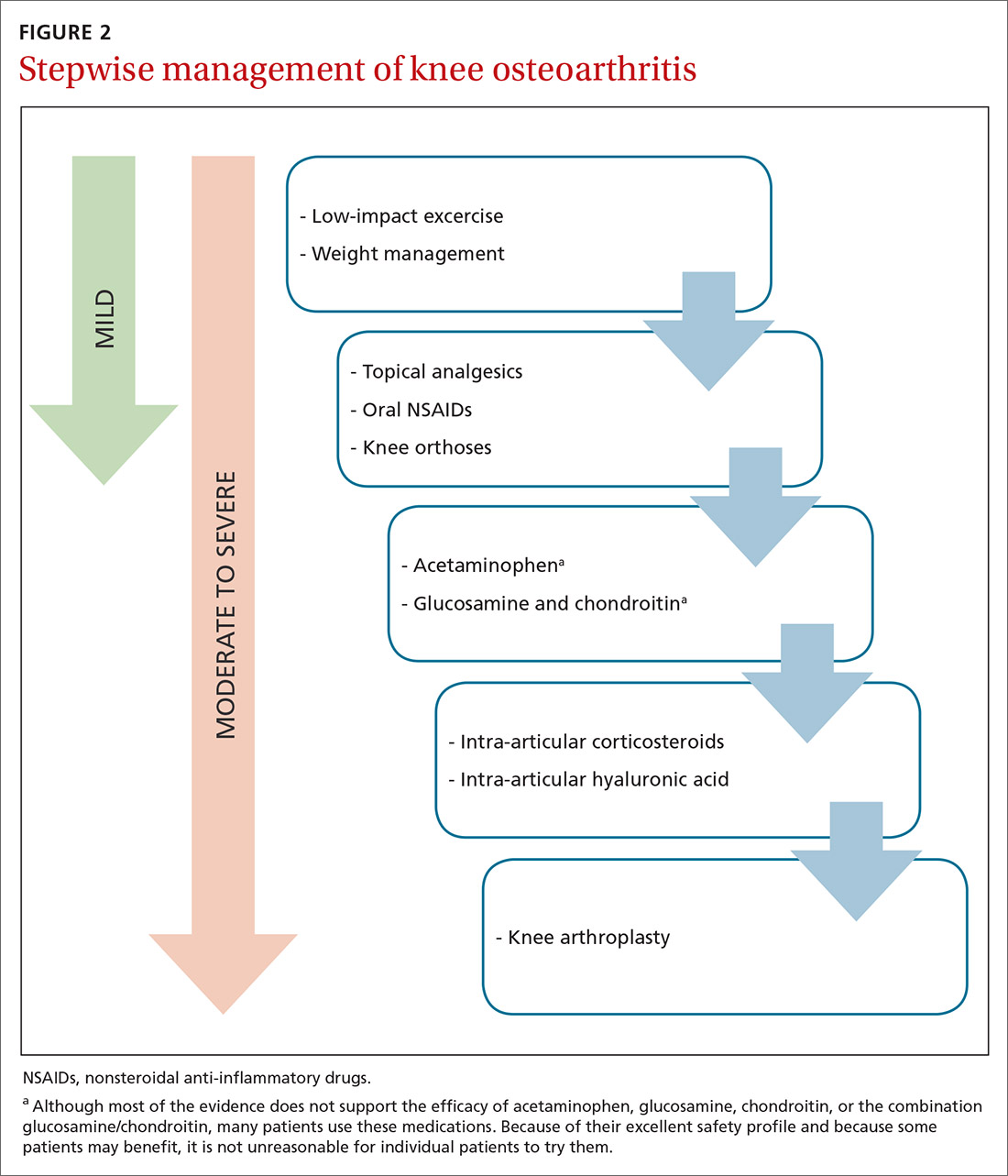

Because there is no cure for OA, the primary goals of treatment are to decrease pain, improve function of the joint, and slow progression of the disease. As a result, a multifaceted treatment approach is usually undertaken that includes weight reduction and exercise therapy and may include pharmacotherapy, depending on the degree of symptoms. FIGURE 2 contains a summary of the stepwise management of knee OA.

Weight management can slow progression of the disease

Obesity is a causative factor in knee OA.12,13 Patients with knee OA who achieve and maintain an appropriate body weight can potentially slow progression of the disease.13,14 One pound of weight loss can lead to a 4-fold reduction in the load exerted on the knee per step.15

Specific methods of weight reduction are beyond the scope of this article; however, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 399 overweight and obese adults with knee OA found that individuals who participated in a dietary intervention or a combined diet and exercise intervention achieved more weight loss than those who undertook exercise alone.16 Additionally, the diet group had greater reductions in knee compression forces compared to the exercise group, and the combined diet and exercise group had less pain and better function than both the diet group and the exercise group.16 This would suggest that both diet and exercise interventions should be employed in the treatment of knee OA, not only for weight management, but also for knee joint health.

What kind of exercise? Evidence exists to support the utilization of various forms of exercise. In general, land-based therapeutic exercise improves knee pain, physical function, and quality of life, but these benefits often last less than 1 year because people often fail to maintain exercise programs for the long term.17

Specific therapies such as yoga, Tai Chi, balance training, and aquatic exercise have shown some minor improvement in symptoms related to knee OA.18-22 Weight-bearing strength training, non–weight-bearing strength training, and aerobic exercise have all been shown to be effective for short-term pain relief in knee OA, with non–weight-bearing strength training being the most effective.23

Continue to: Strengthening of the upper leg muscles...

Strengthening of the upper leg muscles is thought to be one of the factors involved in reducing pain associated with knee OA.24 Strength training, Tai Chi, and aerobic exercise have also been shown to decrease fall risk in the elderly with knee OA.25 In general, lower impact activities (eg, walking, swimming, biking, yoga) are preferred over higher impact activities (eg, running, jumping) in order to lessen pain with exercise.26-28

Knee orthoses: Many forms and mixed findings

Knee braces come in many forms, including soft braces (eg, elastic sleeves, simple hinged braces) and unloading braces. Many of these braces have been purported to help with knee OA although the evidence remains mixed, with a lack of high-quality trials. A systematic review of RCTs comparing various knee braces, foot orthotics, and conservative treatment for the management of medial compartment OA concluded that the optimal choice for orthosis remains unclear, and long-term evidence is lacking.29

The medial unloading (valgus) knee brace is often used to treat medial compartment OA and varus malalignment of the knee by applying a valgus force, thereby reducing the load on the medial compartment. One recent systematic review concluded that medial unloading braces improve pain from medial compartment OA, but whether they improve function and stiffness is unclear.30 Another study showed that compared to conservative treatment alone, valgus knee bracing has some benefit in decreasing pain and improving knee function.31 Additionally, an 8-year prospective study found that the valgus unloading brace can delay the time before patients need to undergo knee arthroplasty.32 However, another prospective study examining the efficacy of valgus bracing at 2.7 years and 11.2 years showed short-term but not long-term benefit.33

Soft knee braces include a variety of elastic sleeves and simple hinged knee braces. These braces are available commercially at most pharmacies and athletic retail stores. Soft braces are thought to improve pain by a thermal and compressive effect, and to provide stability to the knee joint. One systematic review concluded that soft knee braces have a moderate effect on pain and a small-to-moderate effect on self-reported physical function.34 A small trial showed that soft knee braces reduced pain and dynamic instability in individuals with knee OA.35

In summary, many types of soft knee braces exist, but the evidence for recommending them individually or collectively is limited, as high-quality trials are lacking. However, the available evidence does suggest some mild benefit with regard to pain and function with no concern for adverse effects.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy: Oral agents

Acetaminophen. Although people commonly use this over-the-counter analgesic for knee OA pain, recent meta-analyses have shown that acetaminophen provides little to no benefit.36,37 Furthermore, although many believe acetaminophen causes fewer adverse effects than oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), liver, gastrointestinal, and renal complications are not uncommon with long-term acetaminophen use. Nevertheless, a trial of acetaminophen may be beneficial in patients with cardiovascular disease or who are taking oral anticoagulants.

Oral NSAIDs. Many studies have concluded that NSAIDs are more effective at controlling pain from knee OA than acetaminophen.37,38 They are among the most commonly prescribed treatments for knee OA, but patients and their physicians should be cautious about long-term use because of potential cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, and other adverse effects. Although evidence regarding optimal frequency of use is scarce, oral NSAIDs should be used intermittently and at the minimal effective dose in order to decrease the risk of adverse events.

One recent meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that diclofenac at a dose of 150 mg/d is the most effective NSAID for improving pain and function associated with knee OA.37 Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis analyzing multiple pharmacologic treatments found an association between celecoxib and decreased pain from knee OA.39 However, this study also concluded that uncertainty surrounded all of the estimates of effect size for change in pain compared to placebo for all of the pharmacologic treatments included in the study.39

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing celecoxib to no treatment, placebo, naproxen, and diclofenac concluded that celecoxib is slightly better than placebo and the aforementioned NSAIDs in reducing pain and improving function in general OA. However, the authors had reservations regarding pharmaceutical industry involvement in the studies and overall limited data.40

With all of that said, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends strongly for the use of oral NSAIDs in the management of knee OA.41

Continue to: Glucosamine and chondroitin

Glucosamine and chondroitin. Glucosamine and chondroitin are supplements that have gained popularity in the treatment of knee OA. These constituents are found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale for their use. Glucosamine and chondroitin (or a combination of the 2) are associated with few adverse effects, but the evidence to support their use in knee OA management is mixed.

One large double-blind RCT (the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial [GAIT]) concluded that glucosamine, chondroitin, or the combination of the 2 did not have a significant effect on reducing pain from knee OA compared to placebo and did not slow structural joint disease.42 However, this same study found that in a subset of patients with moderate-to-severe knee OA, the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin was mildly effective in reducing pain.42

Multiple studies have shown either no benefit, inconsistent results, or limited benefit of glucosamine and chondroitin in the treatment of knee OA, with the patented crystalline form of glucosamine showing the most efficacy.43-47 The AAOS and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) do not recommend glucosamine and chondroitin for knee OA management.10,41

In summary, the evidence for glucosamine, chondroitin, or a combination of the 2 for knee OA is mixed with likely limited benefit, but because they are associated with few adverse effects, patients may be offered a 3- to 6-month trial of these supplements if other effective options are exhausted.

Injections

Limited-quality evidence suggests that oral NSAIDs and intra-articular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injections are equally efficacious for knee OA pain.38,48 There is insufficient evidence directly comparing oral NSAIDs with IA corticosteroid (CS) injections.

Continue to: HA is found naturally...

HA is found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale behind its use. A network meta-analysis performed by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine concluded that knee OA is more likely to respond to IAHA than to IACS or IA placebo, leading the society to recommend the use of IAHA in knee OA management, especially for patients > 60 years with mild-to-moderate knee OA.9 Conversely, the AAOS does not recommend the use of IAHA, and the ACR does not recommend for or against the use of IAHA.10,41

IACSs are commonly used to provide pain relief in those with moderate-to-severe knee OA. There is evidence that a single IACS injection provides mild pain relief for up to 6 weeks.49 However, there is some concern that repetitive IACS injections may speed cartilage loss. A 2-year randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of repetitive IA triamcinolone vs saline in knee OA found no difference in pain severity and concluded that there was greater cartilage volume loss in the triamcinolone group.50

AAOS does not recommend for or against the use of IACSs, whereas the ACR does recommend for the use of IACSs.10,41 Given the available evidence, conservative use of IACS injections remains an option for patients with refractory moderate-to-severe knee OA.

Topicals

Topical analgesics are often utilized for knee OA because of their efficacy, tolerability, low risk of adverse effects, and ease of use. They are generally recommended over oral NSAIDs in the elderly and in individuals at risk for cardiac, renal, and gastrointestinal complications from oral NSAIDs.

One review found that topical diclofenac and topical ketoprofen were comparable to the oral forms of these medications.51 One RCT concluded that topical and oral diclofenac were equally efficacious in treating knee OA symptoms, although topical diclofenac was associated with significantly fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects.52 In multiple randomized trials, topical diclofenac has shown efficacy compared to placebo.53-55 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs were safe and effective for treating general OA compared to placebo, with diclofenac patches most effective for pain relief and piroxicam most effective for functional improvement.56

Continue to: Topical capsaicin has shown...

Topical capsaicin has shown some efficacy in treating pain associated with knee OA.57 One meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin may be equally efficacious for OA-associated pain relief, although none of the RCTs directly compared the two.58 The major limitation of capsaicin is a patient-reported mild-to-moderate burning sensation with application that may decrease compliance.

Emerging treatments: IA PRP & extended-release IA triamcinolone acetonide

IA platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been investigated for efficacy in treating knee OA. PRP is thought to decrease inflammation in the joint, although its exact mechanism remains unknown.59 Multiple studies have shown some benefit of PRP in reducing pain and improving function in individuals with knee OA, but nearly all of these studies have failed to show a clear benefit of PRP over HA injections.59-63 Additionally, the authors of most of these studies mention a high risk of bias. PRP therapy is expensive and generally is not covered by insurance companies, which precludes its use for many people.

Extended-release (ER) IA triamcinolone acetonide (Zilretta) has shown some superiority to standard IA triamcinolone acetonide in both degree and duration of pain relief for knee OA.64-66 The ER version tolerability did not differ from placebo and also showed prolonged synovial presence, lower systemic absorption, and lower blood glucose elevations compared with standard triamcinolone.64-66

Surgical intervention: A last resort

Select patients with severe pain and disability from knee OA that is refractory to conservative management options should be referred for consideration of knee arthroplasty. Age, weight, OA location, and degree of OA are all considered with respect to knee arthroplasty timing and technique.

There is good evidence that arthroscopy with debridement, on the other hand, is no more effective than conservative management.67

Continue to: Unicompartmental or "partial"...

Unicompartmental or “partial” knee replacements are reserved for select cases when 1 knee compartment has a significantly higher degree of degenerative change.

CASE After reviewing the therapeutic options with your patient, you agree that she will undergo a course of physical therapy and try using topical diclofenac along with a hinged knee brace. Because of the patient’s age and co-morbidities of cardiovascular disease and mild chronic kidney disease, oral NSAIDs are avoided at this time.

The patient returns to the office in 2 months reporting mild improvement in her pain. To provide additional pain relief, an ultrasound-guided IA steroid injection is attempted. The patient also continues home physical therapy, activity modification, topical diclofenac, and use of a hinged knee brace.

She returns to the office 2 months later, reporting continued improvement in her pain. No further intervention is undertaken at this time.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, West Virginia University School of Medicine–Eastern Campus, WVU Medicine Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, 912 Somerset Boulevard, Charles Town, WV 25414; rsprouse@wvumedicine.org.

1. Wallace IJ, Worthington S,Felson DT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:9332-9336.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

3. Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:160-167.

4. Warner SC, Valdes AM. Genetic association studies in osteoarthritis: is it fairytale? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:103-109.

5. Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, et al. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:769-781.

6. Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau MM, et al. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:134-138.

7. Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, et al. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:459-467.

8. Yucesoy B, Charles LE, Baker B, et al. Occupational and genetic risk factors for osteoarthritis: a review. Work. 2015;50:261-273.

9. Trojian TH, Concoff AL, Joy SM, et al. AMSSM scientific statement concerning viscosupplementation injections for knee osteoarthritis: importance for individual patient outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:84-92.

10. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 Recommendations for the Use of Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Therapies in Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465-474.

11. Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116.

12. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, et al. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:18-24.

13. Yusuf E, Bijsterbosch J, Slagboom PE, et al. Body mass index and alignment and their interaction as risk factors for progression of knees with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1117-1122.

14. Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J, et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:329-335.

15. Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, et al. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2026-2032.

16. Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1263-1273.

17. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, et al. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med.

18. Kan L, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6016532.

19. Chang WD, Chen S, Lee CL, et al. The effects of tai chi chuan on improving mind-body health for knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1813979.

20. Takacs J, Krowchuk NM, Garland SJ, et al. Dynamic balance training improves physical function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1586-1593.

21. Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(3):CD005523.

22. Hinman RS, Heywood SE, Day AR. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:32-43.

23. Tanaka R, Ozawa J, Kito N, et al. Efficacy of strengthening or aerobic exercise on pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:1059-1071.

24. Knoop J, Steultjens MP, Roorda LD, et al. Improvement in upper leg muscle strength underlies beneficial effects of exercise therapy in knee osteoarthritis: secondary analysis from a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:171-177.

25. Mat S, Tan MP, Kamaruzzaman SB, et al. Physical therapies for improving balance and reducing falls risk in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44:16-24.

26. Peeler J, Christian M, Cooper J, et al. Managing knee osteoarthritis: the effects of body weight supported physical activity on joint pain, function, and thigh muscle strength. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:518-523.

27. Peeler J, Ripat J. The effect of low-load exercise on joint pain, function, and activities of daily living in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2018;25:135-145.

28. Takacs J, Anderson JE, Leiter JR, et al. Lower body positive pressure: an emerging technology in the battle against knee osteoarthritis? Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:983-991.

29. Duivenvoorden T, Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, et al. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD004020.

30. Gohal C, Shanmugaraj A, Tate P, et al. Effectiveness of valgus offloading knee braces in the treatment of medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2018;10:500-514.

31. Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhaar JA, et al. Brace treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective randomized multi-centre trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:777-783.

32. Lee PY, Winfield TG, Harris SR, et al. Unloading knee brace is a cost-effective method to bridge and delay surgery in unicompartmental knee arthritis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017;2:e000195.

33. Wilson B, Rankin H, Barnes CL. Long-term results of an unloader brace in patients with unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. 2011;34:334-347.

34. Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van der Leeden M, et al. Effect of soft braces on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analyses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:153-163.

35. Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van den Noort JC. Decreased pain and improved dynamic knee instability mediate the beneficial effect of wearing a soft knee brace on activity limitations in persons with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1036-1043.

36. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1225.

37. da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:e21-e33.

38. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54.

39. Gregori D, Giacovelli G, Minto C, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments with long-term pain control in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:2564-2579.

40. Puljak L, Marin A, Vrdoljak D, et al. Celecoxib for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(5):CD009865.

41. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;9:571-576.

42. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808.

43. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

44. Yang S, Eaton CB, McAlindon TE, et al. Effects of glucosamine and chondroitin on treating knee osteoarthritis: an analysis with marginal structural models. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:714-723.

45. Ogata T, Yuki Ideno Y, Masami Akai M,et al. Effects of glucosamine in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:2479-2487.

46. Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD002946.

47. Bruyèreetal O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis—from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4 suppl):S3-S11.

48. Ishijima M, Nakamura T, Shimizu K, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection versus oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a multi-center, randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R18.

49. Juni P, Hari R, Rutjes AW, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(10):CD005328.

50. McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey FW, et al. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1967-1975.

51. Derry S, Conaghan P, Da Silva JA, et al. Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(4):CD007400.

52. Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2002-2012.

53. Wadsworth LT, Kent JD, Holt RJ. Efficacy and safety of diclofenac sodium 2% topical solution for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 4 week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:241-250.

54. Roth SH, Shainhouse JZ. Efficacy and safety of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) in the treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2017-2023.

55. Baer PA, Thomas LM, Shainhouse Z. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a topical diclofenac solution: a randomised controlled, 6-week trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6:44.

56. Zeng C, Wei J, Persson MSM, et al. Relative efficacy and safety of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:642-650.

57. Guedes V, Castro JP, Brito I. Topical capsaicin for pain in osteoarthritis: a literature review. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14:40-45.

58. Persson MSM, Stocks J, Walsh DA, et al. The relative efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and capsaicin in osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:1575-1582.

59. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:339-346.

60. Laudy AB, Bakker EW, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

61. Han Y, Huang H, Pan J, et al. Meta-analysis comparing platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid injection in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2019;20:1418-1429.

62. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

63. Di Martino A, Di Matteo B, Papio T, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid injections for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results at 5 years of a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:347-354.

64. Bodick N, Lufkin J, Willwerth C, et al. An intra-articular, extended-release formulation of triamcinolone acetonide prolongs and amplifies analgesic effect in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:877-888.

65. Conaghan PG, Cohen SB, Berenbaum F, et al. Brief report: a phase IIb trial of a novel extended-release microsphere formulation of triamcinolone acetonide for intraarticular injection in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:204-211.

66. Conaghan PG, Hunter DJ, Cohen SB, et al. Effects of a single intra-articular injection of a microsphere formulation of triamcinolone acetonide on knee osteoarthritis pain: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, multinational study. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2018;100:666–677.

67. Thorlund JB, Juhl CB, Roos EM, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ. 2015;350:h2747.

CASE A 73-year-old woman presents to your clinic with 1 year of gradual-onset left knee pain. The pain is worse at the medial knee and at the beginning and end of the day, with some mild improvement after activity in the morning. The patient has already tried oral acetaminophen, an over-the-counter menthol cream, and a soft elastic knee brace, but these interventions have helped only minimally.

On physical exam, there is no obvious deformity of the knee. There is a bit of small joint effusion without redness or warmth. There is mild tenderness to palpation of the medial joint line. Radiographic findings include osteophytes of the medial and lateral tibial plateaus and medial and lateral femoral condyles with mild joint-space narrowing of the medial compartment, consistent with mild osteoarthritis.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

The knee is the most common joint to be affected by osteoarthritis (OA) and accounts for the majority of the disease’s total burden.1 More than 19% of American adults ages ≥ 45 years have knee OA,1,2 and more than half of the people with symptomatic knee OA in the United States are younger than 65 years of age.3 Longer lifespan and increasing rates of obesity are thought to be driving the increasing prevalence of knee OA, although this remains debated.1 Risk factors for knee OA are outlined in TABLE.1,4-8

Diagnosis: Radiographs are helpful, not essential

The diagnosis of knee OA is relatively straightforward. Gradual onset of knee joint pain is present most days, with pain worse after activity and better with rest. Patients are usually middle-aged or older and/or have a distant history of knee joint injury. Other signs, symptoms, and physical exam findings associated with knee OA include: morning stiffness < 30 minutes, crepitus, instability, range-of-motion deficit, varus or valgus deformity, bony exostosis, joint-line tenderness, joint swelling/effusion, and the absence of erythema/warmth.1,9,10

Although radiographs are not necessary to diagnose knee OA, they can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis by assessing the degree and location of OA and ruling out other pathology. Standing, weight-bearing radiographs are particularly helpful for assessing the degree of joint-space narrowing. In addition to joint-space narrowing, radiographic findings indicative of knee OA include marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cysts. (See FIGURE 1.)

Keep in mind that radiographs are less sensitive for early OA, that the degree of OA seen on radiographs does not correlate well with symptoms, and that radiographic evidence of OA is a common incidental finding—especially in elderly individuals.11 Although not routinely utilized for knee OA diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess for earlier stages of the disease and to rule out pathology associated with the soft tissue and cartilage that is not directly associated with OA.

Continue to: Management

Management: Decrease pain, improve function, slow progression

Because there is no cure for OA, the primary goals of treatment are to decrease pain, improve function of the joint, and slow progression of the disease. As a result, a multifaceted treatment approach is usually undertaken that includes weight reduction and exercise therapy and may include pharmacotherapy, depending on the degree of symptoms. FIGURE 2 contains a summary of the stepwise management of knee OA.

Weight management can slow progression of the disease

Obesity is a causative factor in knee OA.12,13 Patients with knee OA who achieve and maintain an appropriate body weight can potentially slow progression of the disease.13,14 One pound of weight loss can lead to a 4-fold reduction in the load exerted on the knee per step.15

Specific methods of weight reduction are beyond the scope of this article; however, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 399 overweight and obese adults with knee OA found that individuals who participated in a dietary intervention or a combined diet and exercise intervention achieved more weight loss than those who undertook exercise alone.16 Additionally, the diet group had greater reductions in knee compression forces compared to the exercise group, and the combined diet and exercise group had less pain and better function than both the diet group and the exercise group.16 This would suggest that both diet and exercise interventions should be employed in the treatment of knee OA, not only for weight management, but also for knee joint health.

What kind of exercise? Evidence exists to support the utilization of various forms of exercise. In general, land-based therapeutic exercise improves knee pain, physical function, and quality of life, but these benefits often last less than 1 year because people often fail to maintain exercise programs for the long term.17

Specific therapies such as yoga, Tai Chi, balance training, and aquatic exercise have shown some minor improvement in symptoms related to knee OA.18-22 Weight-bearing strength training, non–weight-bearing strength training, and aerobic exercise have all been shown to be effective for short-term pain relief in knee OA, with non–weight-bearing strength training being the most effective.23

Continue to: Strengthening of the upper leg muscles...

Strengthening of the upper leg muscles is thought to be one of the factors involved in reducing pain associated with knee OA.24 Strength training, Tai Chi, and aerobic exercise have also been shown to decrease fall risk in the elderly with knee OA.25 In general, lower impact activities (eg, walking, swimming, biking, yoga) are preferred over higher impact activities (eg, running, jumping) in order to lessen pain with exercise.26-28

Knee orthoses: Many forms and mixed findings

Knee braces come in many forms, including soft braces (eg, elastic sleeves, simple hinged braces) and unloading braces. Many of these braces have been purported to help with knee OA although the evidence remains mixed, with a lack of high-quality trials. A systematic review of RCTs comparing various knee braces, foot orthotics, and conservative treatment for the management of medial compartment OA concluded that the optimal choice for orthosis remains unclear, and long-term evidence is lacking.29

The medial unloading (valgus) knee brace is often used to treat medial compartment OA and varus malalignment of the knee by applying a valgus force, thereby reducing the load on the medial compartment. One recent systematic review concluded that medial unloading braces improve pain from medial compartment OA, but whether they improve function and stiffness is unclear.30 Another study showed that compared to conservative treatment alone, valgus knee bracing has some benefit in decreasing pain and improving knee function.31 Additionally, an 8-year prospective study found that the valgus unloading brace can delay the time before patients need to undergo knee arthroplasty.32 However, another prospective study examining the efficacy of valgus bracing at 2.7 years and 11.2 years showed short-term but not long-term benefit.33

Soft knee braces include a variety of elastic sleeves and simple hinged knee braces. These braces are available commercially at most pharmacies and athletic retail stores. Soft braces are thought to improve pain by a thermal and compressive effect, and to provide stability to the knee joint. One systematic review concluded that soft knee braces have a moderate effect on pain and a small-to-moderate effect on self-reported physical function.34 A small trial showed that soft knee braces reduced pain and dynamic instability in individuals with knee OA.35

In summary, many types of soft knee braces exist, but the evidence for recommending them individually or collectively is limited, as high-quality trials are lacking. However, the available evidence does suggest some mild benefit with regard to pain and function with no concern for adverse effects.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy: Oral agents

Acetaminophen. Although people commonly use this over-the-counter analgesic for knee OA pain, recent meta-analyses have shown that acetaminophen provides little to no benefit.36,37 Furthermore, although many believe acetaminophen causes fewer adverse effects than oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), liver, gastrointestinal, and renal complications are not uncommon with long-term acetaminophen use. Nevertheless, a trial of acetaminophen may be beneficial in patients with cardiovascular disease or who are taking oral anticoagulants.

Oral NSAIDs. Many studies have concluded that NSAIDs are more effective at controlling pain from knee OA than acetaminophen.37,38 They are among the most commonly prescribed treatments for knee OA, but patients and their physicians should be cautious about long-term use because of potential cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, and other adverse effects. Although evidence regarding optimal frequency of use is scarce, oral NSAIDs should be used intermittently and at the minimal effective dose in order to decrease the risk of adverse events.

One recent meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that diclofenac at a dose of 150 mg/d is the most effective NSAID for improving pain and function associated with knee OA.37 Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis analyzing multiple pharmacologic treatments found an association between celecoxib and decreased pain from knee OA.39 However, this study also concluded that uncertainty surrounded all of the estimates of effect size for change in pain compared to placebo for all of the pharmacologic treatments included in the study.39

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing celecoxib to no treatment, placebo, naproxen, and diclofenac concluded that celecoxib is slightly better than placebo and the aforementioned NSAIDs in reducing pain and improving function in general OA. However, the authors had reservations regarding pharmaceutical industry involvement in the studies and overall limited data.40

With all of that said, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends strongly for the use of oral NSAIDs in the management of knee OA.41

Continue to: Glucosamine and chondroitin

Glucosamine and chondroitin. Glucosamine and chondroitin are supplements that have gained popularity in the treatment of knee OA. These constituents are found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale for their use. Glucosamine and chondroitin (or a combination of the 2) are associated with few adverse effects, but the evidence to support their use in knee OA management is mixed.

One large double-blind RCT (the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial [GAIT]) concluded that glucosamine, chondroitin, or the combination of the 2 did not have a significant effect on reducing pain from knee OA compared to placebo and did not slow structural joint disease.42 However, this same study found that in a subset of patients with moderate-to-severe knee OA, the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin was mildly effective in reducing pain.42

Multiple studies have shown either no benefit, inconsistent results, or limited benefit of glucosamine and chondroitin in the treatment of knee OA, with the patented crystalline form of glucosamine showing the most efficacy.43-47 The AAOS and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) do not recommend glucosamine and chondroitin for knee OA management.10,41

In summary, the evidence for glucosamine, chondroitin, or a combination of the 2 for knee OA is mixed with likely limited benefit, but because they are associated with few adverse effects, patients may be offered a 3- to 6-month trial of these supplements if other effective options are exhausted.

Injections

Limited-quality evidence suggests that oral NSAIDs and intra-articular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injections are equally efficacious for knee OA pain.38,48 There is insufficient evidence directly comparing oral NSAIDs with IA corticosteroid (CS) injections.

Continue to: HA is found naturally...

HA is found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale behind its use. A network meta-analysis performed by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine concluded that knee OA is more likely to respond to IAHA than to IACS or IA placebo, leading the society to recommend the use of IAHA in knee OA management, especially for patients > 60 years with mild-to-moderate knee OA.9 Conversely, the AAOS does not recommend the use of IAHA, and the ACR does not recommend for or against the use of IAHA.10,41

IACSs are commonly used to provide pain relief in those with moderate-to-severe knee OA. There is evidence that a single IACS injection provides mild pain relief for up to 6 weeks.49 However, there is some concern that repetitive IACS injections may speed cartilage loss. A 2-year randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of repetitive IA triamcinolone vs saline in knee OA found no difference in pain severity and concluded that there was greater cartilage volume loss in the triamcinolone group.50

AAOS does not recommend for or against the use of IACSs, whereas the ACR does recommend for the use of IACSs.10,41 Given the available evidence, conservative use of IACS injections remains an option for patients with refractory moderate-to-severe knee OA.

Topicals

Topical analgesics are often utilized for knee OA because of their efficacy, tolerability, low risk of adverse effects, and ease of use. They are generally recommended over oral NSAIDs in the elderly and in individuals at risk for cardiac, renal, and gastrointestinal complications from oral NSAIDs.

One review found that topical diclofenac and topical ketoprofen were comparable to the oral forms of these medications.51 One RCT concluded that topical and oral diclofenac were equally efficacious in treating knee OA symptoms, although topical diclofenac was associated with significantly fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects.52 In multiple randomized trials, topical diclofenac has shown efficacy compared to placebo.53-55 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs were safe and effective for treating general OA compared to placebo, with diclofenac patches most effective for pain relief and piroxicam most effective for functional improvement.56

Continue to: Topical capsaicin has shown...

Topical capsaicin has shown some efficacy in treating pain associated with knee OA.57 One meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin may be equally efficacious for OA-associated pain relief, although none of the RCTs directly compared the two.58 The major limitation of capsaicin is a patient-reported mild-to-moderate burning sensation with application that may decrease compliance.

Emerging treatments: IA PRP & extended-release IA triamcinolone acetonide

IA platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been investigated for efficacy in treating knee OA. PRP is thought to decrease inflammation in the joint, although its exact mechanism remains unknown.59 Multiple studies have shown some benefit of PRP in reducing pain and improving function in individuals with knee OA, but nearly all of these studies have failed to show a clear benefit of PRP over HA injections.59-63 Additionally, the authors of most of these studies mention a high risk of bias. PRP therapy is expensive and generally is not covered by insurance companies, which precludes its use for many people.

Extended-release (ER) IA triamcinolone acetonide (Zilretta) has shown some superiority to standard IA triamcinolone acetonide in both degree and duration of pain relief for knee OA.64-66 The ER version tolerability did not differ from placebo and also showed prolonged synovial presence, lower systemic absorption, and lower blood glucose elevations compared with standard triamcinolone.64-66

Surgical intervention: A last resort

Select patients with severe pain and disability from knee OA that is refractory to conservative management options should be referred for consideration of knee arthroplasty. Age, weight, OA location, and degree of OA are all considered with respect to knee arthroplasty timing and technique.

There is good evidence that arthroscopy with debridement, on the other hand, is no more effective than conservative management.67

Continue to: Unicompartmental or "partial"...

Unicompartmental or “partial” knee replacements are reserved for select cases when 1 knee compartment has a significantly higher degree of degenerative change.

CASE After reviewing the therapeutic options with your patient, you agree that she will undergo a course of physical therapy and try using topical diclofenac along with a hinged knee brace. Because of the patient’s age and co-morbidities of cardiovascular disease and mild chronic kidney disease, oral NSAIDs are avoided at this time.

The patient returns to the office in 2 months reporting mild improvement in her pain. To provide additional pain relief, an ultrasound-guided IA steroid injection is attempted. The patient also continues home physical therapy, activity modification, topical diclofenac, and use of a hinged knee brace.

She returns to the office 2 months later, reporting continued improvement in her pain. No further intervention is undertaken at this time.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, West Virginia University School of Medicine–Eastern Campus, WVU Medicine Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, 912 Somerset Boulevard, Charles Town, WV 25414; rsprouse@wvumedicine.org.

CASE A 73-year-old woman presents to your clinic with 1 year of gradual-onset left knee pain. The pain is worse at the medial knee and at the beginning and end of the day, with some mild improvement after activity in the morning. The patient has already tried oral acetaminophen, an over-the-counter menthol cream, and a soft elastic knee brace, but these interventions have helped only minimally.

On physical exam, there is no obvious deformity of the knee. There is a bit of small joint effusion without redness or warmth. There is mild tenderness to palpation of the medial joint line. Radiographic findings include osteophytes of the medial and lateral tibial plateaus and medial and lateral femoral condyles with mild joint-space narrowing of the medial compartment, consistent with mild osteoarthritis.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

The knee is the most common joint to be affected by osteoarthritis (OA) and accounts for the majority of the disease’s total burden.1 More than 19% of American adults ages ≥ 45 years have knee OA,1,2 and more than half of the people with symptomatic knee OA in the United States are younger than 65 years of age.3 Longer lifespan and increasing rates of obesity are thought to be driving the increasing prevalence of knee OA, although this remains debated.1 Risk factors for knee OA are outlined in TABLE.1,4-8

Diagnosis: Radiographs are helpful, not essential

The diagnosis of knee OA is relatively straightforward. Gradual onset of knee joint pain is present most days, with pain worse after activity and better with rest. Patients are usually middle-aged or older and/or have a distant history of knee joint injury. Other signs, symptoms, and physical exam findings associated with knee OA include: morning stiffness < 30 minutes, crepitus, instability, range-of-motion deficit, varus or valgus deformity, bony exostosis, joint-line tenderness, joint swelling/effusion, and the absence of erythema/warmth.1,9,10

Although radiographs are not necessary to diagnose knee OA, they can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis by assessing the degree and location of OA and ruling out other pathology. Standing, weight-bearing radiographs are particularly helpful for assessing the degree of joint-space narrowing. In addition to joint-space narrowing, radiographic findings indicative of knee OA include marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cysts. (See FIGURE 1.)

Keep in mind that radiographs are less sensitive for early OA, that the degree of OA seen on radiographs does not correlate well with symptoms, and that radiographic evidence of OA is a common incidental finding—especially in elderly individuals.11 Although not routinely utilized for knee OA diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess for earlier stages of the disease and to rule out pathology associated with the soft tissue and cartilage that is not directly associated with OA.

Continue to: Management

Management: Decrease pain, improve function, slow progression

Because there is no cure for OA, the primary goals of treatment are to decrease pain, improve function of the joint, and slow progression of the disease. As a result, a multifaceted treatment approach is usually undertaken that includes weight reduction and exercise therapy and may include pharmacotherapy, depending on the degree of symptoms. FIGURE 2 contains a summary of the stepwise management of knee OA.

Weight management can slow progression of the disease

Obesity is a causative factor in knee OA.12,13 Patients with knee OA who achieve and maintain an appropriate body weight can potentially slow progression of the disease.13,14 One pound of weight loss can lead to a 4-fold reduction in the load exerted on the knee per step.15

Specific methods of weight reduction are beyond the scope of this article; however, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 399 overweight and obese adults with knee OA found that individuals who participated in a dietary intervention or a combined diet and exercise intervention achieved more weight loss than those who undertook exercise alone.16 Additionally, the diet group had greater reductions in knee compression forces compared to the exercise group, and the combined diet and exercise group had less pain and better function than both the diet group and the exercise group.16 This would suggest that both diet and exercise interventions should be employed in the treatment of knee OA, not only for weight management, but also for knee joint health.

What kind of exercise? Evidence exists to support the utilization of various forms of exercise. In general, land-based therapeutic exercise improves knee pain, physical function, and quality of life, but these benefits often last less than 1 year because people often fail to maintain exercise programs for the long term.17

Specific therapies such as yoga, Tai Chi, balance training, and aquatic exercise have shown some minor improvement in symptoms related to knee OA.18-22 Weight-bearing strength training, non–weight-bearing strength training, and aerobic exercise have all been shown to be effective for short-term pain relief in knee OA, with non–weight-bearing strength training being the most effective.23

Continue to: Strengthening of the upper leg muscles...

Strengthening of the upper leg muscles is thought to be one of the factors involved in reducing pain associated with knee OA.24 Strength training, Tai Chi, and aerobic exercise have also been shown to decrease fall risk in the elderly with knee OA.25 In general, lower impact activities (eg, walking, swimming, biking, yoga) are preferred over higher impact activities (eg, running, jumping) in order to lessen pain with exercise.26-28

Knee orthoses: Many forms and mixed findings

Knee braces come in many forms, including soft braces (eg, elastic sleeves, simple hinged braces) and unloading braces. Many of these braces have been purported to help with knee OA although the evidence remains mixed, with a lack of high-quality trials. A systematic review of RCTs comparing various knee braces, foot orthotics, and conservative treatment for the management of medial compartment OA concluded that the optimal choice for orthosis remains unclear, and long-term evidence is lacking.29

The medial unloading (valgus) knee brace is often used to treat medial compartment OA and varus malalignment of the knee by applying a valgus force, thereby reducing the load on the medial compartment. One recent systematic review concluded that medial unloading braces improve pain from medial compartment OA, but whether they improve function and stiffness is unclear.30 Another study showed that compared to conservative treatment alone, valgus knee bracing has some benefit in decreasing pain and improving knee function.31 Additionally, an 8-year prospective study found that the valgus unloading brace can delay the time before patients need to undergo knee arthroplasty.32 However, another prospective study examining the efficacy of valgus bracing at 2.7 years and 11.2 years showed short-term but not long-term benefit.33

Soft knee braces include a variety of elastic sleeves and simple hinged knee braces. These braces are available commercially at most pharmacies and athletic retail stores. Soft braces are thought to improve pain by a thermal and compressive effect, and to provide stability to the knee joint. One systematic review concluded that soft knee braces have a moderate effect on pain and a small-to-moderate effect on self-reported physical function.34 A small trial showed that soft knee braces reduced pain and dynamic instability in individuals with knee OA.35

In summary, many types of soft knee braces exist, but the evidence for recommending them individually or collectively is limited, as high-quality trials are lacking. However, the available evidence does suggest some mild benefit with regard to pain and function with no concern for adverse effects.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy: Oral agents

Acetaminophen. Although people commonly use this over-the-counter analgesic for knee OA pain, recent meta-analyses have shown that acetaminophen provides little to no benefit.36,37 Furthermore, although many believe acetaminophen causes fewer adverse effects than oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), liver, gastrointestinal, and renal complications are not uncommon with long-term acetaminophen use. Nevertheless, a trial of acetaminophen may be beneficial in patients with cardiovascular disease or who are taking oral anticoagulants.

Oral NSAIDs. Many studies have concluded that NSAIDs are more effective at controlling pain from knee OA than acetaminophen.37,38 They are among the most commonly prescribed treatments for knee OA, but patients and their physicians should be cautious about long-term use because of potential cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, and other adverse effects. Although evidence regarding optimal frequency of use is scarce, oral NSAIDs should be used intermittently and at the minimal effective dose in order to decrease the risk of adverse events.

One recent meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that diclofenac at a dose of 150 mg/d is the most effective NSAID for improving pain and function associated with knee OA.37 Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis analyzing multiple pharmacologic treatments found an association between celecoxib and decreased pain from knee OA.39 However, this study also concluded that uncertainty surrounded all of the estimates of effect size for change in pain compared to placebo for all of the pharmacologic treatments included in the study.39

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing celecoxib to no treatment, placebo, naproxen, and diclofenac concluded that celecoxib is slightly better than placebo and the aforementioned NSAIDs in reducing pain and improving function in general OA. However, the authors had reservations regarding pharmaceutical industry involvement in the studies and overall limited data.40

With all of that said, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends strongly for the use of oral NSAIDs in the management of knee OA.41

Continue to: Glucosamine and chondroitin

Glucosamine and chondroitin. Glucosamine and chondroitin are supplements that have gained popularity in the treatment of knee OA. These constituents are found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale for their use. Glucosamine and chondroitin (or a combination of the 2) are associated with few adverse effects, but the evidence to support their use in knee OA management is mixed.

One large double-blind RCT (the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial [GAIT]) concluded that glucosamine, chondroitin, or the combination of the 2 did not have a significant effect on reducing pain from knee OA compared to placebo and did not slow structural joint disease.42 However, this same study found that in a subset of patients with moderate-to-severe knee OA, the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin was mildly effective in reducing pain.42

Multiple studies have shown either no benefit, inconsistent results, or limited benefit of glucosamine and chondroitin in the treatment of knee OA, with the patented crystalline form of glucosamine showing the most efficacy.43-47 The AAOS and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) do not recommend glucosamine and chondroitin for knee OA management.10,41

In summary, the evidence for glucosamine, chondroitin, or a combination of the 2 for knee OA is mixed with likely limited benefit, but because they are associated with few adverse effects, patients may be offered a 3- to 6-month trial of these supplements if other effective options are exhausted.

Injections

Limited-quality evidence suggests that oral NSAIDs and intra-articular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injections are equally efficacious for knee OA pain.38,48 There is insufficient evidence directly comparing oral NSAIDs with IA corticosteroid (CS) injections.

Continue to: HA is found naturally...

HA is found naturally in articular cartilage, which explains the rationale behind its use. A network meta-analysis performed by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine concluded that knee OA is more likely to respond to IAHA than to IACS or IA placebo, leading the society to recommend the use of IAHA in knee OA management, especially for patients > 60 years with mild-to-moderate knee OA.9 Conversely, the AAOS does not recommend the use of IAHA, and the ACR does not recommend for or against the use of IAHA.10,41

IACSs are commonly used to provide pain relief in those with moderate-to-severe knee OA. There is evidence that a single IACS injection provides mild pain relief for up to 6 weeks.49 However, there is some concern that repetitive IACS injections may speed cartilage loss. A 2-year randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of repetitive IA triamcinolone vs saline in knee OA found no difference in pain severity and concluded that there was greater cartilage volume loss in the triamcinolone group.50

AAOS does not recommend for or against the use of IACSs, whereas the ACR does recommend for the use of IACSs.10,41 Given the available evidence, conservative use of IACS injections remains an option for patients with refractory moderate-to-severe knee OA.

Topicals

Topical analgesics are often utilized for knee OA because of their efficacy, tolerability, low risk of adverse effects, and ease of use. They are generally recommended over oral NSAIDs in the elderly and in individuals at risk for cardiac, renal, and gastrointestinal complications from oral NSAIDs.

One review found that topical diclofenac and topical ketoprofen were comparable to the oral forms of these medications.51 One RCT concluded that topical and oral diclofenac were equally efficacious in treating knee OA symptoms, although topical diclofenac was associated with significantly fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects.52 In multiple randomized trials, topical diclofenac has shown efficacy compared to placebo.53-55 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs were safe and effective for treating general OA compared to placebo, with diclofenac patches most effective for pain relief and piroxicam most effective for functional improvement.56

Continue to: Topical capsaicin has shown...

Topical capsaicin has shown some efficacy in treating pain associated with knee OA.57 One meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin may be equally efficacious for OA-associated pain relief, although none of the RCTs directly compared the two.58 The major limitation of capsaicin is a patient-reported mild-to-moderate burning sensation with application that may decrease compliance.

Emerging treatments: IA PRP & extended-release IA triamcinolone acetonide

IA platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been investigated for efficacy in treating knee OA. PRP is thought to decrease inflammation in the joint, although its exact mechanism remains unknown.59 Multiple studies have shown some benefit of PRP in reducing pain and improving function in individuals with knee OA, but nearly all of these studies have failed to show a clear benefit of PRP over HA injections.59-63 Additionally, the authors of most of these studies mention a high risk of bias. PRP therapy is expensive and generally is not covered by insurance companies, which precludes its use for many people.

Extended-release (ER) IA triamcinolone acetonide (Zilretta) has shown some superiority to standard IA triamcinolone acetonide in both degree and duration of pain relief for knee OA.64-66 The ER version tolerability did not differ from placebo and also showed prolonged synovial presence, lower systemic absorption, and lower blood glucose elevations compared with standard triamcinolone.64-66

Surgical intervention: A last resort

Select patients with severe pain and disability from knee OA that is refractory to conservative management options should be referred for consideration of knee arthroplasty. Age, weight, OA location, and degree of OA are all considered with respect to knee arthroplasty timing and technique.

There is good evidence that arthroscopy with debridement, on the other hand, is no more effective than conservative management.67

Continue to: Unicompartmental or "partial"...

Unicompartmental or “partial” knee replacements are reserved for select cases when 1 knee compartment has a significantly higher degree of degenerative change.

CASE After reviewing the therapeutic options with your patient, you agree that she will undergo a course of physical therapy and try using topical diclofenac along with a hinged knee brace. Because of the patient’s age and co-morbidities of cardiovascular disease and mild chronic kidney disease, oral NSAIDs are avoided at this time.

The patient returns to the office in 2 months reporting mild improvement in her pain. To provide additional pain relief, an ultrasound-guided IA steroid injection is attempted. The patient also continues home physical therapy, activity modification, topical diclofenac, and use of a hinged knee brace.

She returns to the office 2 months later, reporting continued improvement in her pain. No further intervention is undertaken at this time.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, West Virginia University School of Medicine–Eastern Campus, WVU Medicine Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, 912 Somerset Boulevard, Charles Town, WV 25414; rsprouse@wvumedicine.org.

1. Wallace IJ, Worthington S,Felson DT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:9332-9336.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

3. Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:160-167.

4. Warner SC, Valdes AM. Genetic association studies in osteoarthritis: is it fairytale? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:103-109.

5. Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, et al. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:769-781.

6. Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau MM, et al. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:134-138.

7. Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, et al. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:459-467.

8. Yucesoy B, Charles LE, Baker B, et al. Occupational and genetic risk factors for osteoarthritis: a review. Work. 2015;50:261-273.

9. Trojian TH, Concoff AL, Joy SM, et al. AMSSM scientific statement concerning viscosupplementation injections for knee osteoarthritis: importance for individual patient outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:84-92.

10. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 Recommendations for the Use of Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Therapies in Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465-474.

11. Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116.

12. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, et al. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:18-24.

13. Yusuf E, Bijsterbosch J, Slagboom PE, et al. Body mass index and alignment and their interaction as risk factors for progression of knees with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1117-1122.

14. Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J, et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:329-335.

15. Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, et al. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2026-2032.

16. Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1263-1273.

17. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, et al. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med.

18. Kan L, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6016532.

19. Chang WD, Chen S, Lee CL, et al. The effects of tai chi chuan on improving mind-body health for knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1813979.

20. Takacs J, Krowchuk NM, Garland SJ, et al. Dynamic balance training improves physical function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1586-1593.

21. Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(3):CD005523.

22. Hinman RS, Heywood SE, Day AR. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:32-43.

23. Tanaka R, Ozawa J, Kito N, et al. Efficacy of strengthening or aerobic exercise on pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:1059-1071.

24. Knoop J, Steultjens MP, Roorda LD, et al. Improvement in upper leg muscle strength underlies beneficial effects of exercise therapy in knee osteoarthritis: secondary analysis from a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:171-177.

25. Mat S, Tan MP, Kamaruzzaman SB, et al. Physical therapies for improving balance and reducing falls risk in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44:16-24.

26. Peeler J, Christian M, Cooper J, et al. Managing knee osteoarthritis: the effects of body weight supported physical activity on joint pain, function, and thigh muscle strength. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:518-523.

27. Peeler J, Ripat J. The effect of low-load exercise on joint pain, function, and activities of daily living in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2018;25:135-145.

28. Takacs J, Anderson JE, Leiter JR, et al. Lower body positive pressure: an emerging technology in the battle against knee osteoarthritis? Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:983-991.

29. Duivenvoorden T, Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, et al. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD004020.

30. Gohal C, Shanmugaraj A, Tate P, et al. Effectiveness of valgus offloading knee braces in the treatment of medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2018;10:500-514.

31. Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhaar JA, et al. Brace treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective randomized multi-centre trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:777-783.

32. Lee PY, Winfield TG, Harris SR, et al. Unloading knee brace is a cost-effective method to bridge and delay surgery in unicompartmental knee arthritis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017;2:e000195.

33. Wilson B, Rankin H, Barnes CL. Long-term results of an unloader brace in patients with unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. 2011;34:334-347.

34. Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van der Leeden M, et al. Effect of soft braces on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analyses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:153-163.

35. Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van den Noort JC. Decreased pain and improved dynamic knee instability mediate the beneficial effect of wearing a soft knee brace on activity limitations in persons with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1036-1043.

36. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1225.

37. da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:e21-e33.

38. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54.

39. Gregori D, Giacovelli G, Minto C, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments with long-term pain control in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:2564-2579.

40. Puljak L, Marin A, Vrdoljak D, et al. Celecoxib for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(5):CD009865.

41. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;9:571-576.

42. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808.

43. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

44. Yang S, Eaton CB, McAlindon TE, et al. Effects of glucosamine and chondroitin on treating knee osteoarthritis: an analysis with marginal structural models. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:714-723.

45. Ogata T, Yuki Ideno Y, Masami Akai M,et al. Effects of glucosamine in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:2479-2487.

46. Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD002946.

47. Bruyèreetal O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis—from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4 suppl):S3-S11.

48. Ishijima M, Nakamura T, Shimizu K, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection versus oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a multi-center, randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R18.

49. Juni P, Hari R, Rutjes AW, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(10):CD005328.

50. McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey FW, et al. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1967-1975.

51. Derry S, Conaghan P, Da Silva JA, et al. Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(4):CD007400.

52. Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2002-2012.

53. Wadsworth LT, Kent JD, Holt RJ. Efficacy and safety of diclofenac sodium 2% topical solution for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 4 week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:241-250.

54. Roth SH, Shainhouse JZ. Efficacy and safety of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) in the treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2017-2023.

55. Baer PA, Thomas LM, Shainhouse Z. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a topical diclofenac solution: a randomised controlled, 6-week trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6:44.

56. Zeng C, Wei J, Persson MSM, et al. Relative efficacy and safety of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:642-650.

57. Guedes V, Castro JP, Brito I. Topical capsaicin for pain in osteoarthritis: a literature review. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14:40-45.

58. Persson MSM, Stocks J, Walsh DA, et al. The relative efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and capsaicin in osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:1575-1582.

59. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:339-346.

60. Laudy AB, Bakker EW, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

61. Han Y, Huang H, Pan J, et al. Meta-analysis comparing platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid injection in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2019;20:1418-1429.

62. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.