User login

Decline in ambulatory function

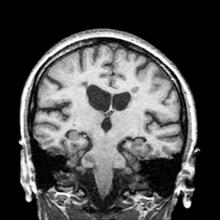

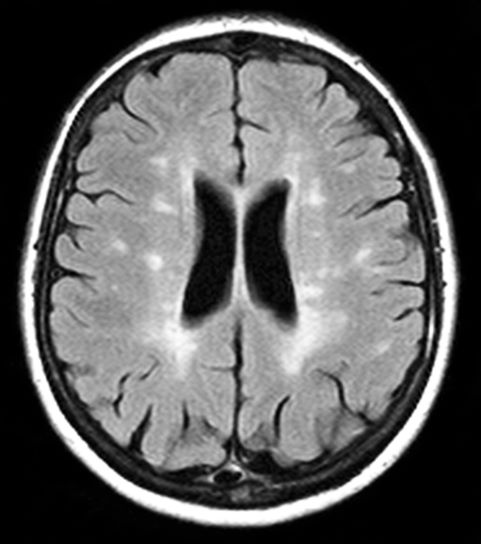

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

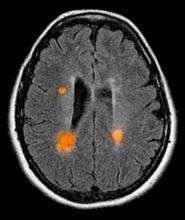

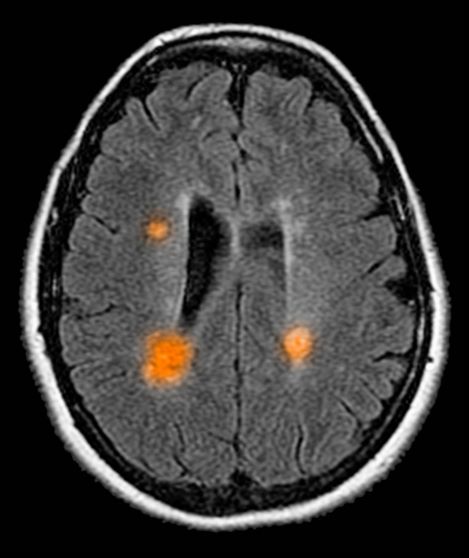

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 59-year-old man presents with worsening decline in ambulatory function and worsening bladder function. He reports "difficulty getting around" for the past year and a half, which he theorized might be because of arthritis, aging, or many years of biking. He presented to his primary care physician 2 months ago and was referred to rheumatology. His height is 5 ft 11 in and his weight is 166 lb (BMI 23.1). The patient subsequently reported a decreased attention span to the rheumatologist. He has no other significant medical or surgical history, though his brother has psoriatic arthritis. MRI shows multiple brain lesions without gadolinium enhancement and multiple spinal cord lesions.

Multiple Sclerosis: Etiology

Decreased visual acuity and paresthesia

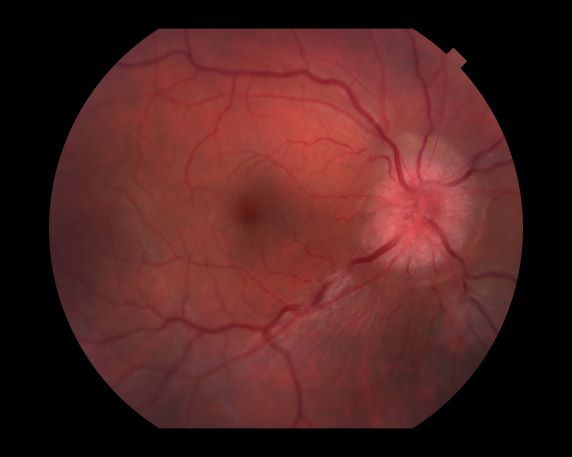

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

A 44-year-old woman presents with decreased visual acuity, painful ophthalmoplegia, photophobia, and paresthesia of the left hand. The patient's ocular history was unremarkable. Her medical history was significant only for recurrent urinary tract infections. She did not have a history of neurologic problems and reported that she did not have dizziness, tingling, tremors, sensory changes, speech changes, or focal weaknesses. Besides current use of naproxen, she said she was not taking any other medications. Her family ocular history was significant for glaucoma in her father and paternal grandfather. Her maternal grandfather died at age 58 of multiple sclerosis (MS).

3-year-history of difficulty walking

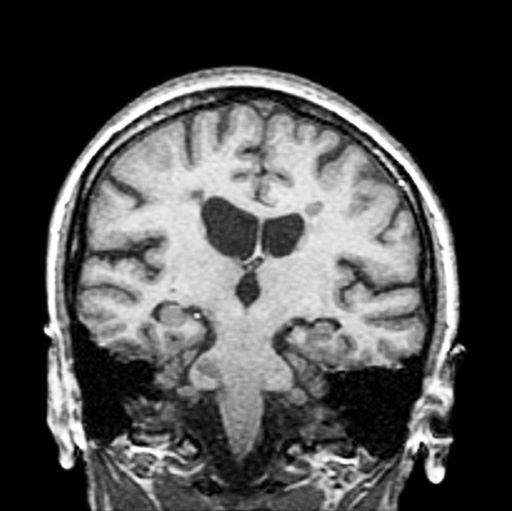

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 51-year-old woman presents with a 3-year history of difficulty walking. She says that it is difficult to pinpoint when her walking problems began but reports that it has been gradual. She recalls about 10 years back a history of numbness and tingling in her hands that improved over the course of a few weeks without any further workup. She also recalls blurry vision and loss of color perception in her left eye 5 years ago while traveling for work. Because the symptoms resolved on their own over 6-8 weeks, she never sought care. MRI shows plaques of demyelination.

Multiple Sclerosis: Treatment & Management

Boy with slightly impaired coordination

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 10-year-old boy, typically active, presents with slightly impaired coordination and facial weakness. His parents noticed that his gait in particular seems impaired, though to his knowledge he had not been injured. His mother reports a history of meningoencephalitis. A sagittal T2-weighted MRI sequence shows a portion of the brainstem with a large demyelinating plaque in the dorsal part of the medulla and several other lesions in the periventricular regions of the brain. Spinal fluid is normal.

Fatigued absent of medical history

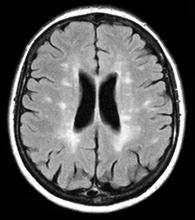

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 51-year-old woman reports that she has been feeling fatigued despite the absence of any significant medical history. Although she usually walks to work, lately she has not had the energy to participate in her daily routine. She notes that over the past 2 weeks, colleagues have asked her if she is feeling well due to unusual ocular symptoms. She explains that several months ago she felt similarly unwell, with fatigue and generalized weakness, but her symptoms seemed to resolve. Upon presentation, she has diplopia on lateral gaze. MRI reveals lesions with high T2 signal intensity.