User login

Prior resections increase anastomotic leak risk in Crohn’s

SEATTLE – The risk of anastomotic leaks after bowel resection for Crohn’s disease is more than three times higher in patients who have had prior resections, according to a review of 206 patients at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

There were 20 anastomotic leaks within 30 days of resection in those patients, giving an overall leakage rate of 10%. Among the 123 patients who were having their first resection, however, the rate was 5% (6/123). The risk jumped to 17% in the 83 who had prior resections (14/83) and 23% (7) among the 30 patients who had two or more prior resections, which is “substantially higher than we talk about in the clinic when we are counseling these people,” said lead investigator Forrest Johnston, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at Lahey.

The findings are important because prior resections have not, until now, been formally recognized as a risk factor for anastomotic leaks, and repeat resections are common in Crohn’s. “When you see patients for repeat intestinal resections, you have to look at them as a higher risk population in terms of your counseling and algorithms,” Dr. Johnston said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting. In addition, to mitigate the increased risk, Crohn’s patients who have repeat resections need additional attention to correct modifiable risk factors before surgery, such as steroid use and malnutrition. “Some of these patients are pushed through the clinic,” but “they deserve a bit more time.”

The heightened risk is also “another factor that might tip you one way or another” in choosing surgical options. “It’s certainly something to think about,” he said.

The new and prior resection patients in the study were well matched in terms of known risk factors for leakage, including age, sex, preoperative serum albumin, and use of immune suppressing medications. “The increased risk of leak is not explained by preoperative nutritional status or medication use,” Dr. Johnston said.

Estimated blood loss, OR time, types of procedures, hand-sewn versus stapled anastomoses, and other surgical variables were also similar.

The lack of significant differences between the groups raises the question of why repeat resections leak more. “That’s the million dollar question. My thought is that repeat resections indicate a greater severity of Crohn’s disease. I think there’s microvascular disease that’s affecting their tissue integrity, but we don’t appreciate it at the time of their anastomosis. If it was obvious at the time of surgery, patients wouldn’t be put together. They’d just get a stoma and be done with it,” Dr. Johnston said

About 80% of both first-time and repeat procedures were ileocolic resections secondary to obstruction, generally without bowel prep. Repeat procedures were performed a mean of 15 years after the first operation. Most initial resections were done laparoscopically, and a good portion of repeat procedures were open. Anorectal cases were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Johnston said his team looked into the issue after noticing that repeat patients “seemed to leak a little bit more than we expected.”

The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – The risk of anastomotic leaks after bowel resection for Crohn’s disease is more than three times higher in patients who have had prior resections, according to a review of 206 patients at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

There were 20 anastomotic leaks within 30 days of resection in those patients, giving an overall leakage rate of 10%. Among the 123 patients who were having their first resection, however, the rate was 5% (6/123). The risk jumped to 17% in the 83 who had prior resections (14/83) and 23% (7) among the 30 patients who had two or more prior resections, which is “substantially higher than we talk about in the clinic when we are counseling these people,” said lead investigator Forrest Johnston, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at Lahey.

The findings are important because prior resections have not, until now, been formally recognized as a risk factor for anastomotic leaks, and repeat resections are common in Crohn’s. “When you see patients for repeat intestinal resections, you have to look at them as a higher risk population in terms of your counseling and algorithms,” Dr. Johnston said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting. In addition, to mitigate the increased risk, Crohn’s patients who have repeat resections need additional attention to correct modifiable risk factors before surgery, such as steroid use and malnutrition. “Some of these patients are pushed through the clinic,” but “they deserve a bit more time.”

The heightened risk is also “another factor that might tip you one way or another” in choosing surgical options. “It’s certainly something to think about,” he said.

The new and prior resection patients in the study were well matched in terms of known risk factors for leakage, including age, sex, preoperative serum albumin, and use of immune suppressing medications. “The increased risk of leak is not explained by preoperative nutritional status or medication use,” Dr. Johnston said.

Estimated blood loss, OR time, types of procedures, hand-sewn versus stapled anastomoses, and other surgical variables were also similar.

The lack of significant differences between the groups raises the question of why repeat resections leak more. “That’s the million dollar question. My thought is that repeat resections indicate a greater severity of Crohn’s disease. I think there’s microvascular disease that’s affecting their tissue integrity, but we don’t appreciate it at the time of their anastomosis. If it was obvious at the time of surgery, patients wouldn’t be put together. They’d just get a stoma and be done with it,” Dr. Johnston said

About 80% of both first-time and repeat procedures were ileocolic resections secondary to obstruction, generally without bowel prep. Repeat procedures were performed a mean of 15 years after the first operation. Most initial resections were done laparoscopically, and a good portion of repeat procedures were open. Anorectal cases were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Johnston said his team looked into the issue after noticing that repeat patients “seemed to leak a little bit more than we expected.”

The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – The risk of anastomotic leaks after bowel resection for Crohn’s disease is more than three times higher in patients who have had prior resections, according to a review of 206 patients at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

There were 20 anastomotic leaks within 30 days of resection in those patients, giving an overall leakage rate of 10%. Among the 123 patients who were having their first resection, however, the rate was 5% (6/123). The risk jumped to 17% in the 83 who had prior resections (14/83) and 23% (7) among the 30 patients who had two or more prior resections, which is “substantially higher than we talk about in the clinic when we are counseling these people,” said lead investigator Forrest Johnston, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at Lahey.

The findings are important because prior resections have not, until now, been formally recognized as a risk factor for anastomotic leaks, and repeat resections are common in Crohn’s. “When you see patients for repeat intestinal resections, you have to look at them as a higher risk population in terms of your counseling and algorithms,” Dr. Johnston said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting. In addition, to mitigate the increased risk, Crohn’s patients who have repeat resections need additional attention to correct modifiable risk factors before surgery, such as steroid use and malnutrition. “Some of these patients are pushed through the clinic,” but “they deserve a bit more time.”

The heightened risk is also “another factor that might tip you one way or another” in choosing surgical options. “It’s certainly something to think about,” he said.

The new and prior resection patients in the study were well matched in terms of known risk factors for leakage, including age, sex, preoperative serum albumin, and use of immune suppressing medications. “The increased risk of leak is not explained by preoperative nutritional status or medication use,” Dr. Johnston said.

Estimated blood loss, OR time, types of procedures, hand-sewn versus stapled anastomoses, and other surgical variables were also similar.

The lack of significant differences between the groups raises the question of why repeat resections leak more. “That’s the million dollar question. My thought is that repeat resections indicate a greater severity of Crohn’s disease. I think there’s microvascular disease that’s affecting their tissue integrity, but we don’t appreciate it at the time of their anastomosis. If it was obvious at the time of surgery, patients wouldn’t be put together. They’d just get a stoma and be done with it,” Dr. Johnston said

About 80% of both first-time and repeat procedures were ileocolic resections secondary to obstruction, generally without bowel prep. Repeat procedures were performed a mean of 15 years after the first operation. Most initial resections were done laparoscopically, and a good portion of repeat procedures were open. Anorectal cases were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Johnston said his team looked into the issue after noticing that repeat patients “seemed to leak a little bit more than we expected.”

The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The number of prior resections correlated almost perfectly with an increasing risk of anastomotic leakage (r = 0.998); the odds ratio for leakage with prior resection, compared with initial resection, was 3.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-9.4; P less than .005).

Data source: A review of 206 Crohn’ patients.

Disclosures: The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

No easy answers for parastomal hernia repair

SEATTLE – At present, laparoscopic Sugarbaker repair is probably the best surgical option for parastomal hernias when stomas can’t be reversed, according to Mark Gudgeon, MS, FRCS, a consultant general surgeon at the Frimley Park Hospital in England.

Parastomal hernias are common in colorectal surgery; more than a quarter of ileostomy stomas and well over half of colostomy stomas herniate within 10 years of placement, leading to pain, leakage, appliance problems, and embarrassment for patients. There’s also the risk of bowel obstruction and strangulation. “It’s something that’s a challenge to all of us. It’s a very difficult problem,” Dr. Gudgeon said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

It can be difficult to decide whether or not to even offer patients a surgical fix because they often fail, and sometimes lead to fistulas and well-known mesh complications. Obese patients are “a no-go because they do not do well, and neither do smokers. Both are things patients have an opportunity to correct before we go ahead with surgery,” Dr. Gudgeon said.

On top of that, about 6% of repair patients die from complications. Patients “don’t believe that at first, but when you rub it in, a lot of them will change their minds” about surgery. “These patients don’t do well,” so avoid surgery when possible, he said. “Pain can be dealt with; leakage can be dealt with; cosmesis can be accepted,” especially with the help of stoma specialists who are experts in the art of appliance fit and support garments, Dr. Gudgeon said.

If the decision to operate is made, forget about suture repair, Dr. Gudgeon recommended. It should be “abandoned. I know it still goes on, but the evidence speaks for itself: [hernias] just come back again.”

Dr. Gudgeon suggested that it may be best to reverse the stoma, if possible, and repair the defect. Relocating the stoma “is always an attractive alternative,” and laparoscopic mesh keyhole repairs are straightforward. But the risk of recurrence is high, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently found that there’s not much difference between synthetic and biologic mesh, so Dr. Gudgeon said he usually opts for synthetics because they are less expensive.

He reported speakers’ fees from Intuitive, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

SEATTLE – At present, laparoscopic Sugarbaker repair is probably the best surgical option for parastomal hernias when stomas can’t be reversed, according to Mark Gudgeon, MS, FRCS, a consultant general surgeon at the Frimley Park Hospital in England.

Parastomal hernias are common in colorectal surgery; more than a quarter of ileostomy stomas and well over half of colostomy stomas herniate within 10 years of placement, leading to pain, leakage, appliance problems, and embarrassment for patients. There’s also the risk of bowel obstruction and strangulation. “It’s something that’s a challenge to all of us. It’s a very difficult problem,” Dr. Gudgeon said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

It can be difficult to decide whether or not to even offer patients a surgical fix because they often fail, and sometimes lead to fistulas and well-known mesh complications. Obese patients are “a no-go because they do not do well, and neither do smokers. Both are things patients have an opportunity to correct before we go ahead with surgery,” Dr. Gudgeon said.

On top of that, about 6% of repair patients die from complications. Patients “don’t believe that at first, but when you rub it in, a lot of them will change their minds” about surgery. “These patients don’t do well,” so avoid surgery when possible, he said. “Pain can be dealt with; leakage can be dealt with; cosmesis can be accepted,” especially with the help of stoma specialists who are experts in the art of appliance fit and support garments, Dr. Gudgeon said.

If the decision to operate is made, forget about suture repair, Dr. Gudgeon recommended. It should be “abandoned. I know it still goes on, but the evidence speaks for itself: [hernias] just come back again.”

Dr. Gudgeon suggested that it may be best to reverse the stoma, if possible, and repair the defect. Relocating the stoma “is always an attractive alternative,” and laparoscopic mesh keyhole repairs are straightforward. But the risk of recurrence is high, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently found that there’s not much difference between synthetic and biologic mesh, so Dr. Gudgeon said he usually opts for synthetics because they are less expensive.

He reported speakers’ fees from Intuitive, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

SEATTLE – At present, laparoscopic Sugarbaker repair is probably the best surgical option for parastomal hernias when stomas can’t be reversed, according to Mark Gudgeon, MS, FRCS, a consultant general surgeon at the Frimley Park Hospital in England.

Parastomal hernias are common in colorectal surgery; more than a quarter of ileostomy stomas and well over half of colostomy stomas herniate within 10 years of placement, leading to pain, leakage, appliance problems, and embarrassment for patients. There’s also the risk of bowel obstruction and strangulation. “It’s something that’s a challenge to all of us. It’s a very difficult problem,” Dr. Gudgeon said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

It can be difficult to decide whether or not to even offer patients a surgical fix because they often fail, and sometimes lead to fistulas and well-known mesh complications. Obese patients are “a no-go because they do not do well, and neither do smokers. Both are things patients have an opportunity to correct before we go ahead with surgery,” Dr. Gudgeon said.

On top of that, about 6% of repair patients die from complications. Patients “don’t believe that at first, but when you rub it in, a lot of them will change their minds” about surgery. “These patients don’t do well,” so avoid surgery when possible, he said. “Pain can be dealt with; leakage can be dealt with; cosmesis can be accepted,” especially with the help of stoma specialists who are experts in the art of appliance fit and support garments, Dr. Gudgeon said.

If the decision to operate is made, forget about suture repair, Dr. Gudgeon recommended. It should be “abandoned. I know it still goes on, but the evidence speaks for itself: [hernias] just come back again.”

Dr. Gudgeon suggested that it may be best to reverse the stoma, if possible, and repair the defect. Relocating the stoma “is always an attractive alternative,” and laparoscopic mesh keyhole repairs are straightforward. But the risk of recurrence is high, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently found that there’s not much difference between synthetic and biologic mesh, so Dr. Gudgeon said he usually opts for synthetics because they are less expensive.

He reported speakers’ fees from Intuitive, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Loop ileostomy tops colectomy for IBD rescue

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies.

Data source: A report on 34 patients with severe, acute inflammatory bowel disease colitis.

Disclosures: The presenter had no disclosures.

Statins might protect against rectal anastomotic leaks

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The statin group had a reduced risk of sepsis (OR, 0.712; 95% CI, 0.535-0.948; P = .020), and, while statins were not associated with a reduction in anastomotic leaks overall, they were protective in subgroup analysis of patients who had rectal resections, which are especially prone to leakage (OR, 0.260; 95% CI, 0.112-0.605, P = .002).

Data source: A review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures.

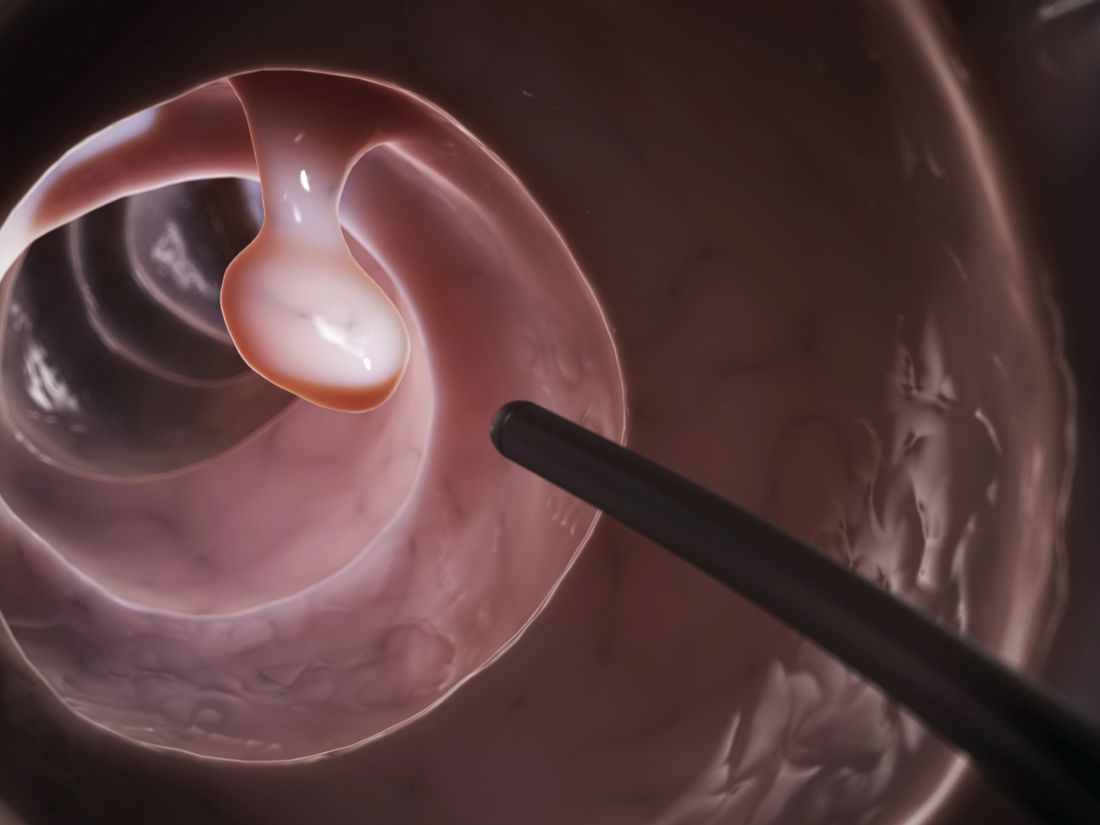

Colonoscopy patients prefer propofol over fentanyl/midazolam

SEATTLE – As patient satisfaction becomes increasingly important for reimbursements, it might be a good idea to switch to propofol for colonoscopies.

The reason is because patients prefer propofol over standard-of-care fentanyl/midazolam as their anesthetic for outpatient colonoscopies, according to a randomized, blinded trial at a single center. Importantly, clinical assessment also showed that propofol outperformed fentanyl/midazolam in terms of hypoxia, pain, nausea, and procedural difficulties.

“Our study demonstrated the superiority of propofol over fentanyl/midazolam in an outpatient setting from both a patient satisfaction standpoint and from a provider prospective,” said lead investigator Anantha Padmanabhan, MD, a colorectal surgeon with Mount Carmel Health, Columbus, Ohio.

The short duration of action and quick turnaround time have led to an increase in the use of propofol for outpatient procedures. It’s been studied extensively for safety and efficacy, but patient preference has not been well documented. The investigators wanted to look into the issue because patient satisfaction has become an important metric for reimbursement, Dr. Padmanabhan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, where the study was presented.

Patients were randomly assigned to propofol or fentanyl/midazolam in the colonoscopy suite at the Taylor Station Surgical Center in Columbus. Anesthesia personnel administered the assigned anesthetic, and circulating nurses rated the difficulty of the procedure. Patients were surveyed after they came to, and again over the phone at least 24 hours after discharge.

Fewer propofol patients reported pain greater than zero during the procedure (2% versus 6%); fewer remembered being awake (2% versus 17%); and fewer had complications (2.7% versus 11.7%); 21 patients in the fentanyl/midazolam group had intraoperative hypoxia, versus 1 in the propofol group. Eleven fentanyl/midazolam patients had postprocedure nausea and vomiting, versus one propofol patient.

Nurses rated 26% of fentanyl/midazolam procedures as “difficult,” compared to 4.7% in the propofol group. Mean induction time was 2.1 minutes with propofol and 3.2 minutes with fentanyl/midazolam; mean procedure time was about 13 minutes in both groups. The cecal intubation rate was 100% in both groups, and there were no perforations.

Propofol patients reacted less during the procedure; an audience member wondered if the loss of feedback was a problem for Dr. Padmanabhan.

“We use propofol in a very light sedation, and sometimes we do get feedback, but more importantly we feel the technique of colonoscopy is as much by feel as it is by vision. If you feel that the scope is not going in correctly, you should pull back then try the loop reduction maneuvers,” he said.

The most common indication for colonoscopy was a history of polyps, followed by general colon screening. Patients in both groups were a mean of 61 years old, and about evenly split between the sexes. Body mass index was a mean of 30 kg/m2 in both groups. There were no between-group differences in comorbidities; hypertension and diabetes were the most common.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – As patient satisfaction becomes increasingly important for reimbursements, it might be a good idea to switch to propofol for colonoscopies.

The reason is because patients prefer propofol over standard-of-care fentanyl/midazolam as their anesthetic for outpatient colonoscopies, according to a randomized, blinded trial at a single center. Importantly, clinical assessment also showed that propofol outperformed fentanyl/midazolam in terms of hypoxia, pain, nausea, and procedural difficulties.

“Our study demonstrated the superiority of propofol over fentanyl/midazolam in an outpatient setting from both a patient satisfaction standpoint and from a provider prospective,” said lead investigator Anantha Padmanabhan, MD, a colorectal surgeon with Mount Carmel Health, Columbus, Ohio.

The short duration of action and quick turnaround time have led to an increase in the use of propofol for outpatient procedures. It’s been studied extensively for safety and efficacy, but patient preference has not been well documented. The investigators wanted to look into the issue because patient satisfaction has become an important metric for reimbursement, Dr. Padmanabhan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, where the study was presented.

Patients were randomly assigned to propofol or fentanyl/midazolam in the colonoscopy suite at the Taylor Station Surgical Center in Columbus. Anesthesia personnel administered the assigned anesthetic, and circulating nurses rated the difficulty of the procedure. Patients were surveyed after they came to, and again over the phone at least 24 hours after discharge.

Fewer propofol patients reported pain greater than zero during the procedure (2% versus 6%); fewer remembered being awake (2% versus 17%); and fewer had complications (2.7% versus 11.7%); 21 patients in the fentanyl/midazolam group had intraoperative hypoxia, versus 1 in the propofol group. Eleven fentanyl/midazolam patients had postprocedure nausea and vomiting, versus one propofol patient.

Nurses rated 26% of fentanyl/midazolam procedures as “difficult,” compared to 4.7% in the propofol group. Mean induction time was 2.1 minutes with propofol and 3.2 minutes with fentanyl/midazolam; mean procedure time was about 13 minutes in both groups. The cecal intubation rate was 100% in both groups, and there were no perforations.

Propofol patients reacted less during the procedure; an audience member wondered if the loss of feedback was a problem for Dr. Padmanabhan.

“We use propofol in a very light sedation, and sometimes we do get feedback, but more importantly we feel the technique of colonoscopy is as much by feel as it is by vision. If you feel that the scope is not going in correctly, you should pull back then try the loop reduction maneuvers,” he said.

The most common indication for colonoscopy was a history of polyps, followed by general colon screening. Patients in both groups were a mean of 61 years old, and about evenly split between the sexes. Body mass index was a mean of 30 kg/m2 in both groups. There were no between-group differences in comorbidities; hypertension and diabetes were the most common.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – As patient satisfaction becomes increasingly important for reimbursements, it might be a good idea to switch to propofol for colonoscopies.

The reason is because patients prefer propofol over standard-of-care fentanyl/midazolam as their anesthetic for outpatient colonoscopies, according to a randomized, blinded trial at a single center. Importantly, clinical assessment also showed that propofol outperformed fentanyl/midazolam in terms of hypoxia, pain, nausea, and procedural difficulties.

“Our study demonstrated the superiority of propofol over fentanyl/midazolam in an outpatient setting from both a patient satisfaction standpoint and from a provider prospective,” said lead investigator Anantha Padmanabhan, MD, a colorectal surgeon with Mount Carmel Health, Columbus, Ohio.

The short duration of action and quick turnaround time have led to an increase in the use of propofol for outpatient procedures. It’s been studied extensively for safety and efficacy, but patient preference has not been well documented. The investigators wanted to look into the issue because patient satisfaction has become an important metric for reimbursement, Dr. Padmanabhan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, where the study was presented.

Patients were randomly assigned to propofol or fentanyl/midazolam in the colonoscopy suite at the Taylor Station Surgical Center in Columbus. Anesthesia personnel administered the assigned anesthetic, and circulating nurses rated the difficulty of the procedure. Patients were surveyed after they came to, and again over the phone at least 24 hours after discharge.

Fewer propofol patients reported pain greater than zero during the procedure (2% versus 6%); fewer remembered being awake (2% versus 17%); and fewer had complications (2.7% versus 11.7%); 21 patients in the fentanyl/midazolam group had intraoperative hypoxia, versus 1 in the propofol group. Eleven fentanyl/midazolam patients had postprocedure nausea and vomiting, versus one propofol patient.

Nurses rated 26% of fentanyl/midazolam procedures as “difficult,” compared to 4.7% in the propofol group. Mean induction time was 2.1 minutes with propofol and 3.2 minutes with fentanyl/midazolam; mean procedure time was about 13 minutes in both groups. The cecal intubation rate was 100% in both groups, and there were no perforations.

Propofol patients reacted less during the procedure; an audience member wondered if the loss of feedback was a problem for Dr. Padmanabhan.

“We use propofol in a very light sedation, and sometimes we do get feedback, but more importantly we feel the technique of colonoscopy is as much by feel as it is by vision. If you feel that the scope is not going in correctly, you should pull back then try the loop reduction maneuvers,” he said.

The most common indication for colonoscopy was a history of polyps, followed by general colon screening. Patients in both groups were a mean of 61 years old, and about evenly split between the sexes. Body mass index was a mean of 30 kg/m2 in both groups. There were no between-group differences in comorbidities; hypertension and diabetes were the most common.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 300 patients randomized to propofol were more likely than were the 300 randomized to standard-of-care fentanyl/midazolam to state that they were “very satisfied” with their anesthesia during the procedure (86.3% versus 74%).

Data source: Randomized, blinded trial of 600 patients at a single center.

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Consider intraperitoneal ropivacaine for colectomy ERAS

SEATTLE – Intraperitoneal ropivacaine decreases postoperative pain and improves functional recovery after laparoscopic colectomy, according to randomized, blinded trial from the Royal Adelaide (Australia) Hospital.

“We recommend routine inclusion of IPLA [intraperitoneal local anesthetic] in the multimodal analgesia component of ERAS [enhanced-recovery-after-surgery] programs for laparoscopic colectomy,” the investigators concluded.

Recovery was smoother in the ropivacaine group. On a 90-point surgical recovery scale assessing fatigue, mental function, and the ability to do normal daily activities, ropivacaine patients were a few points ahead on days 1 and 3; the gap widened to about 10 points on days 7, 30, and 45. Ropivacaine might have helped reduced inflammation, accounting for the extended benefit, Dr. Lewis said.

Pain control was better with ropivacaine, as well. Ropivacaine patients were about 15-20 points lower on 50-point scales assessing both visceral and abdominal pain at postop hours 3 and 24, and day 7. The findings were statistically significant.

Several trends also favored ropivacaine. Ropivacaine patients had their first bowel movement at around 70 hours postop, versus about 82 hours in the control group. They were also discharged almost a day sooner, and had less postop vomiting. Just one patient in the ropivacaine group was diagnosed with ileus, versus four in the control arm.

There was also a trend for less opioid use in the ropivacaine group, which Dr. Lewis suspected would have been statistically significant if the trial had more patients.

Ropivacaine patients were a mean of 67 years old, versus 62 years old in the control group. There were slightly more men than women in each arm. The mean body mass index in the ropivacaine group was 28.5 kg/m2, and in the control group 26.4 kg/m2. Ropivacaine was discontinued in two patients due to possible toxicity.

An audience member noted that intravenous lidocaine has shown similar benefits in abdominal surgery.

The investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Intraperitoneal ropivacaine decreases postoperative pain and improves functional recovery after laparoscopic colectomy, according to randomized, blinded trial from the Royal Adelaide (Australia) Hospital.

“We recommend routine inclusion of IPLA [intraperitoneal local anesthetic] in the multimodal analgesia component of ERAS [enhanced-recovery-after-surgery] programs for laparoscopic colectomy,” the investigators concluded.

Recovery was smoother in the ropivacaine group. On a 90-point surgical recovery scale assessing fatigue, mental function, and the ability to do normal daily activities, ropivacaine patients were a few points ahead on days 1 and 3; the gap widened to about 10 points on days 7, 30, and 45. Ropivacaine might have helped reduced inflammation, accounting for the extended benefit, Dr. Lewis said.

Pain control was better with ropivacaine, as well. Ropivacaine patients were about 15-20 points lower on 50-point scales assessing both visceral and abdominal pain at postop hours 3 and 24, and day 7. The findings were statistically significant.

Several trends also favored ropivacaine. Ropivacaine patients had their first bowel movement at around 70 hours postop, versus about 82 hours in the control group. They were also discharged almost a day sooner, and had less postop vomiting. Just one patient in the ropivacaine group was diagnosed with ileus, versus four in the control arm.

There was also a trend for less opioid use in the ropivacaine group, which Dr. Lewis suspected would have been statistically significant if the trial had more patients.

Ropivacaine patients were a mean of 67 years old, versus 62 years old in the control group. There were slightly more men than women in each arm. The mean body mass index in the ropivacaine group was 28.5 kg/m2, and in the control group 26.4 kg/m2. Ropivacaine was discontinued in two patients due to possible toxicity.

An audience member noted that intravenous lidocaine has shown similar benefits in abdominal surgery.

The investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Intraperitoneal ropivacaine decreases postoperative pain and improves functional recovery after laparoscopic colectomy, according to randomized, blinded trial from the Royal Adelaide (Australia) Hospital.

“We recommend routine inclusion of IPLA [intraperitoneal local anesthetic] in the multimodal analgesia component of ERAS [enhanced-recovery-after-surgery] programs for laparoscopic colectomy,” the investigators concluded.

Recovery was smoother in the ropivacaine group. On a 90-point surgical recovery scale assessing fatigue, mental function, and the ability to do normal daily activities, ropivacaine patients were a few points ahead on days 1 and 3; the gap widened to about 10 points on days 7, 30, and 45. Ropivacaine might have helped reduced inflammation, accounting for the extended benefit, Dr. Lewis said.

Pain control was better with ropivacaine, as well. Ropivacaine patients were about 15-20 points lower on 50-point scales assessing both visceral and abdominal pain at postop hours 3 and 24, and day 7. The findings were statistically significant.

Several trends also favored ropivacaine. Ropivacaine patients had their first bowel movement at around 70 hours postop, versus about 82 hours in the control group. They were also discharged almost a day sooner, and had less postop vomiting. Just one patient in the ropivacaine group was diagnosed with ileus, versus four in the control arm.

There was also a trend for less opioid use in the ropivacaine group, which Dr. Lewis suspected would have been statistically significant if the trial had more patients.

Ropivacaine patients were a mean of 67 years old, versus 62 years old in the control group. There were slightly more men than women in each arm. The mean body mass index in the ropivacaine group was 28.5 kg/m2, and in the control group 26.4 kg/m2. Ropivacaine was discontinued in two patients due to possible toxicity.

An audience member noted that intravenous lidocaine has shown similar benefits in abdominal surgery.

The investigators had no disclosures.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On a 90-point surgical recovery scale assessing fatigue, mental function, and the ability to do normal daily activities, ropivacaine patients were a few points ahead of saline controls on postop days 1 and 3; the gap widened to about 10 points on days 7, 30, and 45.

Data source: Randomized, blinded trial with 51 patients

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures.

Sooner is better than later for acute UC surgery

AT ASCRS 2017

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

There has to be “a conversation with the gastroenterologist to strike the right balance between medical and surgical therapy. Early surgical intervention” should be considered, lead author and general surgery resident Ira Leeds, MD, said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

AGA Resource

Visit www.gastro.org/ibd for patient education guides that you can share with your patients to help them understand and manage their ulcerative colitis and IBD.

AT ASCRS 2017

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

There has to be “a conversation with the gastroenterologist to strike the right balance between medical and surgical therapy. Early surgical intervention” should be considered, lead author and general surgery resident Ira Leeds, MD, said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

AGA Resource

Visit www.gastro.org/ibd for patient education guides that you can share with your patients to help them understand and manage their ulcerative colitis and IBD.

AT ASCRS 2017

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

There has to be “a conversation with the gastroenterologist to strike the right balance between medical and surgical therapy. Early surgical intervention” should be considered, lead author and general surgery resident Ira Leeds, MD, said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

AGA Resource

Visit www.gastro.org/ibd for patient education guides that you can share with your patients to help them understand and manage their ulcerative colitis and IBD.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations.

Data source: Review of almost 2,000 patients in the National Inpatient Sample

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

There has to be “a conversation with the gastroenterologist to strike the right balance between medical and surgical therapy. Early surgical intervention” should be considered, lead author and general surgery resident Ira Leeds, MD, said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

Sooner is better than later for acute UC surgery

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Postponing surgery for acute ulcerative colitis more than a day increases postoperative complications, lengths of stay, and hospital costs, according to a review by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, of almost 2,000 patients.

It’s not uncommon to wait 5 or even 10 days to give biologics a chance to work when patients are admitted for acute ulcerative colitis (UC). Based on the review, however, “we believe that the need for prolonged medical therapy and resuscitation in this patient population prior to colectomy may be overstated,” and that “the lasting effects of persistent inflammation cascade are underestimated.”

The team reviewed 1,953 index UC admissions with emergent non-elective abdominal surgery in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2008-13; 546 patients (28%) had early operations - within 24 hours of admission – and the other 1,407 had operations after that time.

Although it’s impossible to say for sure given the limits of administrative data in the NIS, patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations. The findings were similar for both overall length of stay and post-op length of stay.

Renal complications (8% versus 14%), pulmonary complications (20% versus 25%), and thromboembolic events (4% versus 6%) were also less common in the early surgery group. On multivariable analysis, delayed surgery increased the complication rate by 64%.

With fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, early operations were also less expensive, with a mean total hospitalization cost of $19,985 versus $34,258. The findings were all statistically significant.

Dr. Leeds noted the limits of the study; medical management regimes and the reasons for variations in surgical timing are unknown, among other things. “This is not the final answer on what to do with patients like this, but it opens the door to prospective studies that could control” for such variables, he said.

Early surgery patients were more likely to be male (57% versus 51%) and from households with incomes higher than the national median. There were no difference in age, race, comorbidities, region, or hospital type between the two groups.

Dr. Leeds said he had no disclosures.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who had surgery soon after admission were probably sicker. Even so, they were less likely to have complications than patients in the delayed surgery group (55% versus 43%), and they had shorter hospital stays, with just 8% in the hospital past 21 days, versus 29% of patients who had delayed operations.

Data source: Review of almost 2,000 patients in the National Inpatient Sample

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures.

Anal dysplasia surveillance called into question

SEATTLE – Aggressive screening and treatment of HPV anal dysplasia probably doesn’t decrease the incidence of anal cancer, even in high-risk groups, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Southern California.

The increase in anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) over the past 20 years has led to surveillance programs for anal dysplasia in many institutions, based on the assumption that finding and destroying the lesions will prevent anal cancer, similar to the reason why polyps are removed during colonoscopy to prevent colon cancer, said lead investigator Marco Tomassi, MD, a general surgeon with Kaiser in San Diego.

Kaiser in Southern California doesn’t have an intensive surveillance program for anal HPV. Instead, high risk patients – those with HIV, past cervical cancer, anogenital warts, among others – are screened with digital rectal exams and anoscopy every 3-12 months, and only anal warts and other grossly abnormal growths are removed.

Physicians there do not routinely use high resolution anoscopy (HRA), Pap smears, and other techniques to identify and destroy microscopic foci of dysplasia, as in more intensive programs.

To see how the approach has worked, Dr. Tomassi and his colleagues reviewed the incidence of anal SCC among almost 6 million Kaiser patients from 2005 through 2015.

The cumulative incidence in all groups of patients, even those at risk for the disease, was less than 1%; 425 of the 460 anal cancers (92%) were in the general population, among patients who would not have been part of a high risk surveillance program.

Even without an aggressive surveillance program, high grade anal dysplasia was identified in 377 patients; their incidence of anal SCC was 0.8%, the highest found in the study.

There were no incident cases of SCC among the 133 HIV patients with anal dysplasia. Among over 5,000 HIV patients in the study, the anal SCC incidence was 0.09%. In the general population of 5.86 million, it was 0.01%.

“The cumulative incidence in our group, despite not performing ablative techniques for dysplasia, was comparable to those institutions that routinely perform high resolution anoscopy and destruction of dysplasia. The low rate of malignant conversion suggests that aggressive surveillance regimens, such as HRA, may lead to unnecessary procedures even in high risk patients,” Dr. Tomassi said.

Intensive surveillance doesn’t seem to make much difference because “the incidence of anal cancer is very low even in very high risk populations,” and “most SCC cases develop in the general population,” so “regimens dedicated to identifying cancer in high risk groups will ultimate miss the majority of patients who will succumb to this disease,” he said.

“It’s rare that I come to a meeting and hear a paper that’s going to change my practice. Thank you for that,” an audience member said after Dr. Tomassi presented his findings at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

Dr. Tomassi did not have any disclosures.

SEATTLE – Aggressive screening and treatment of HPV anal dysplasia probably doesn’t decrease the incidence of anal cancer, even in high-risk groups, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Southern California.