User login

Anxiety associated with structural brain differences in children with epilepsy

MONTREAL – The brains of children who have been recently diagnosed with both epilepsy and anxiety are markedly different from those children who have seizures but are anxiety free, a study has shown.

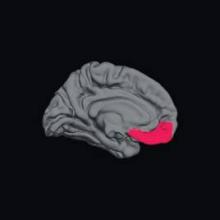

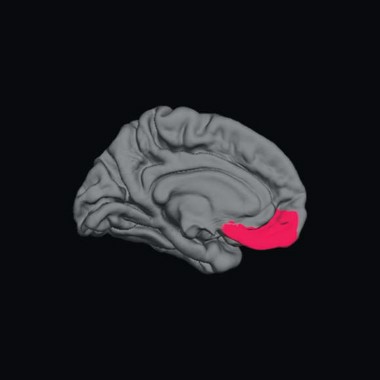

These differences include significantly larger left amygdala, and prefrontal cortices that are thinner in the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right front pole regions – a pattern known to be associated with anxiety and mood disorders in the general population.

Since these children have been diagnosed with epilepsy recently, — and thus have not had years of seizures – these findings may shed new light on the "chicken or egg" association of epilepsy and anxiety, Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., said at the 30th International Epilepsy Conference.

"Seizures are unpredictable, frightening, and are often viewed as a significant factor precipitating anxiety," said Dr. Jones of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "In contrast, these results suggest the presence of abnormal underlying neurobiology affecting subcortical and cortical regions implicated in anxiety in the general population."

She and her colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine brain structure in a cohort of 139 children aged 8-18 years: 25 with epilepsy and anxiety, 64 with epilepsy and no anxiety, and 50 healthy age-matched controls. The children’s average age was 13 years, with an average age of seizure onset of 12 years in those without anxiety and 11 years in those with anxiety. Most were taking one antiepileptic medication, but six in each group were not taking any. Two in the epilepsy/anxiety group were taking multiple antiepileptic medications.

In the epilepsy-only group, most (56%) had an idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome; 42% had a localization-related syndrome, and one was unclassified.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 68% had a localization-related syndrome and 32%, an idiopathic generalized syndrome.

All of the patients were assessed within 12 months of their epilepsy diagnosis. They all had a normal neurologic exam and a normal clinical MRI. They completed the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia questionnaire. The T1-weighted MRI scans were analyzed with the Free Surfer image analysis program.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 11 children had a specific phobia, 8 had separation anxiety disorder, 6 had a social phobia, 5 had generalized anxiety disorder, and 3 had an anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Eight children had a diagnosis of more than one anxiety disorder.

The control group had a significantly higher average IQ (108) than did the epileptic children with and without anxiety (99.8 and 101.4, respectively). Only 10% of the control subjects had academic problems – children with epilepsy had significantly more academic problems in both groups (44% in the epilepsy/anxiety group and 50% of the epilepsy-only group).

Structural brain measurements showed differences between the two patient groups, relative to the healthy control group. The children with epilepsy and anxiety had significantly larger left amygdala volume than did the epilepsy-only group.

Dr. Jones also found significant differences in cortical thickness in several key areas of the prefrontal cortex. In the epilepsy/anxiety group, the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right frontal pole regions of cortex were significantly thinner than in the epilepsy-only group.

These observations support previous findings in children with disorders such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and phobias in the general population, and may be indicative of an abnormal system of emotion regulation involving top-down control of the amygdala via prefrontal cortical connections, Dr. Jones said in an interview.

Her group is currently examining this brain circuitry using diffusion tensor imaging, which allows researchers to image connective fibers in the brain. "Perhaps most importantly, these results suggest that it is important to recognize and treat anxiety early in the course of epilepsy, particularly because there is a relationship between anxiety in childhood leading to ongoing mental health issues in adulthood," she said.

Dr. Jana Jones said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MONTREAL – The brains of children who have been recently diagnosed with both epilepsy and anxiety are markedly different from those children who have seizures but are anxiety free, a study has shown.

These differences include significantly larger left amygdala, and prefrontal cortices that are thinner in the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right front pole regions – a pattern known to be associated with anxiety and mood disorders in the general population.

Since these children have been diagnosed with epilepsy recently, — and thus have not had years of seizures – these findings may shed new light on the "chicken or egg" association of epilepsy and anxiety, Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., said at the 30th International Epilepsy Conference.

"Seizures are unpredictable, frightening, and are often viewed as a significant factor precipitating anxiety," said Dr. Jones of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "In contrast, these results suggest the presence of abnormal underlying neurobiology affecting subcortical and cortical regions implicated in anxiety in the general population."

She and her colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine brain structure in a cohort of 139 children aged 8-18 years: 25 with epilepsy and anxiety, 64 with epilepsy and no anxiety, and 50 healthy age-matched controls. The children’s average age was 13 years, with an average age of seizure onset of 12 years in those without anxiety and 11 years in those with anxiety. Most were taking one antiepileptic medication, but six in each group were not taking any. Two in the epilepsy/anxiety group were taking multiple antiepileptic medications.

In the epilepsy-only group, most (56%) had an idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome; 42% had a localization-related syndrome, and one was unclassified.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 68% had a localization-related syndrome and 32%, an idiopathic generalized syndrome.

All of the patients were assessed within 12 months of their epilepsy diagnosis. They all had a normal neurologic exam and a normal clinical MRI. They completed the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia questionnaire. The T1-weighted MRI scans were analyzed with the Free Surfer image analysis program.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 11 children had a specific phobia, 8 had separation anxiety disorder, 6 had a social phobia, 5 had generalized anxiety disorder, and 3 had an anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Eight children had a diagnosis of more than one anxiety disorder.

The control group had a significantly higher average IQ (108) than did the epileptic children with and without anxiety (99.8 and 101.4, respectively). Only 10% of the control subjects had academic problems – children with epilepsy had significantly more academic problems in both groups (44% in the epilepsy/anxiety group and 50% of the epilepsy-only group).

Structural brain measurements showed differences between the two patient groups, relative to the healthy control group. The children with epilepsy and anxiety had significantly larger left amygdala volume than did the epilepsy-only group.

Dr. Jones also found significant differences in cortical thickness in several key areas of the prefrontal cortex. In the epilepsy/anxiety group, the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right frontal pole regions of cortex were significantly thinner than in the epilepsy-only group.

These observations support previous findings in children with disorders such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and phobias in the general population, and may be indicative of an abnormal system of emotion regulation involving top-down control of the amygdala via prefrontal cortical connections, Dr. Jones said in an interview.

Her group is currently examining this brain circuitry using diffusion tensor imaging, which allows researchers to image connective fibers in the brain. "Perhaps most importantly, these results suggest that it is important to recognize and treat anxiety early in the course of epilepsy, particularly because there is a relationship between anxiety in childhood leading to ongoing mental health issues in adulthood," she said.

Dr. Jana Jones said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MONTREAL – The brains of children who have been recently diagnosed with both epilepsy and anxiety are markedly different from those children who have seizures but are anxiety free, a study has shown.

These differences include significantly larger left amygdala, and prefrontal cortices that are thinner in the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right front pole regions – a pattern known to be associated with anxiety and mood disorders in the general population.

Since these children have been diagnosed with epilepsy recently, — and thus have not had years of seizures – these findings may shed new light on the "chicken or egg" association of epilepsy and anxiety, Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., said at the 30th International Epilepsy Conference.

"Seizures are unpredictable, frightening, and are often viewed as a significant factor precipitating anxiety," said Dr. Jones of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "In contrast, these results suggest the presence of abnormal underlying neurobiology affecting subcortical and cortical regions implicated in anxiety in the general population."

She and her colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine brain structure in a cohort of 139 children aged 8-18 years: 25 with epilepsy and anxiety, 64 with epilepsy and no anxiety, and 50 healthy age-matched controls. The children’s average age was 13 years, with an average age of seizure onset of 12 years in those without anxiety and 11 years in those with anxiety. Most were taking one antiepileptic medication, but six in each group were not taking any. Two in the epilepsy/anxiety group were taking multiple antiepileptic medications.

In the epilepsy-only group, most (56%) had an idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome; 42% had a localization-related syndrome, and one was unclassified.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 68% had a localization-related syndrome and 32%, an idiopathic generalized syndrome.

All of the patients were assessed within 12 months of their epilepsy diagnosis. They all had a normal neurologic exam and a normal clinical MRI. They completed the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia questionnaire. The T1-weighted MRI scans were analyzed with the Free Surfer image analysis program.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 11 children had a specific phobia, 8 had separation anxiety disorder, 6 had a social phobia, 5 had generalized anxiety disorder, and 3 had an anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Eight children had a diagnosis of more than one anxiety disorder.

The control group had a significantly higher average IQ (108) than did the epileptic children with and without anxiety (99.8 and 101.4, respectively). Only 10% of the control subjects had academic problems – children with epilepsy had significantly more academic problems in both groups (44% in the epilepsy/anxiety group and 50% of the epilepsy-only group).

Structural brain measurements showed differences between the two patient groups, relative to the healthy control group. The children with epilepsy and anxiety had significantly larger left amygdala volume than did the epilepsy-only group.

Dr. Jones also found significant differences in cortical thickness in several key areas of the prefrontal cortex. In the epilepsy/anxiety group, the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right frontal pole regions of cortex were significantly thinner than in the epilepsy-only group.

These observations support previous findings in children with disorders such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and phobias in the general population, and may be indicative of an abnormal system of emotion regulation involving top-down control of the amygdala via prefrontal cortical connections, Dr. Jones said in an interview.

Her group is currently examining this brain circuitry using diffusion tensor imaging, which allows researchers to image connective fibers in the brain. "Perhaps most importantly, these results suggest that it is important to recognize and treat anxiety early in the course of epilepsy, particularly because there is a relationship between anxiety in childhood leading to ongoing mental health issues in adulthood," she said.

Dr. Jana Jones said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT IEC 2013

Major finding: Compared with the children with epilepsy alone, the brains of children with newly diagnosed epilepsy and comorbid anxiety showed significant differences in key areas associated with mood regulation.

Data source: A study comparing brain imaging among 25 children with epilepsy and anxiety, 64 with epilepsy only, and 50 healthy, age-matched controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Jana Jones said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Epilepsy patients can face long-term social problems

MONTREAL – Adults who have long-standing epilepsy often have many social difficulties to contend with regardless of whether their childhood seizures have remitted or not, according to a 30-year longitudinal study.

The outcomes of adults who had three different types of childhood epilepsies were "amazingly similar," with high rates of social and romantic isolation, low educational achievement, and psychiatric diagnoses, Dr. Carol Camfield said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

Even those whose seizures had remitted and who were off medication were still likely to have at least one marker of poor social outcome, said Dr. Camfield, a professor of pediatrics at the Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S.

The finding highlights the need for more research into interventions that can address these long-term issues, she said. "They require from all of us prospective interventions in schooling, socialization, employment, and sexuality," she said. "And that’s a lot to ask from a pediatrician."

Her study looked at almost 3 decades of follow-up data on patients included in the Nova Scotia childhood population-based epilepsy cohort. This cohort comprises 692 adults – all the children who were diagnosed with epilepsy in the province in 1977-1985.

From this group, she selected 137 who had epilepsy only, normal intelligence, and a normal neurologic exam. These patients included 23 with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), 34 with generalized tonic-clonic seizures alone (GTCA), and 80 with focal seizures with secondary generalization (SEC gen).

The median age of onset ranged from 7 years in the GTCA and SEC gen groups to 10 years in the JME group. Age at last follow-up visit ranged from a median of 29 years for GTCA patients, to 35 years for SEC gen patients, to 36 years for JME patients.

Dr. Camfield examined eight social outcomes in each group:

• High school graduation. Subjects with JME fared the best in education. A high school diploma was not achieved by 13% of JME patients, compared with 40% of GTCA and 32% of SEC gen patients.

• Unable to name a single close friend. A quarter of GTCA patients were unable to name a close friend, compared with 9% of JME and 8% of SEC gen patients.

• Unemployment. The groups had similar rates of unemployment (31% JME, 33% GTCA, and 23% SEC gen).

• A psychiatric diagnosis other than attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. SEC gen patients were significantly less likely than were the others to have a psychiatric diagnosis other than ADHD (15% vs. 39% JME and 27% GTCA).

• A criminal conviction. All three groups had similar rates of convictions (4% JME, 7% GTCA, and 4% SEC gen).

• No romantic relationship of more than 3 months. Patients with GTCA were more likely to have never experienced a lasting romantic relationship (24% vs. 17% JME and 14% SEC gen)

• Living alone at the end of follow-up. At the final follow-up, SEC gen patients were significantly less likely to be living alone than were the other groups (8% vs. 30% JME and 23% GTCA).

• Pregnancy outside a stable relationship of more than 6 months. There was some indication of sexual impulsivity in the JME and GTCA groups, Dr. Camfield said. If these patients had become pregnant or caused a pregnancy, it was much more likely to have occurred outside of a stable relationship of at least 6 months’ duration, compared with those in the SEC gen group (79% and 65% vs. 37%).

However, when looking at social outcomes as a whole, there were no significant between-group differences. The majority of each group had at least one of the outcome measures (74% JMW, 76% GTCA, 62% SEC gen). It was not uncommon for patients to have two or more of the outcomes, Dr. Camfield said (22% JME, 21% GTCA, 10% SEC gen).

Remission, defined as being seizure free for at least 5 years and off all antiepileptic drugs, occurred in 40% of the JME group, 75% of the GTCA group, and 81% of the SEC gen group. This clearly indicates that social outcomes remained independent of remission status, Dr. Camfield said.

She had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MONTREAL – Adults who have long-standing epilepsy often have many social difficulties to contend with regardless of whether their childhood seizures have remitted or not, according to a 30-year longitudinal study.

The outcomes of adults who had three different types of childhood epilepsies were "amazingly similar," with high rates of social and romantic isolation, low educational achievement, and psychiatric diagnoses, Dr. Carol Camfield said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

Even those whose seizures had remitted and who were off medication were still likely to have at least one marker of poor social outcome, said Dr. Camfield, a professor of pediatrics at the Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S.

The finding highlights the need for more research into interventions that can address these long-term issues, she said. "They require from all of us prospective interventions in schooling, socialization, employment, and sexuality," she said. "And that’s a lot to ask from a pediatrician."

Her study looked at almost 3 decades of follow-up data on patients included in the Nova Scotia childhood population-based epilepsy cohort. This cohort comprises 692 adults – all the children who were diagnosed with epilepsy in the province in 1977-1985.

From this group, she selected 137 who had epilepsy only, normal intelligence, and a normal neurologic exam. These patients included 23 with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), 34 with generalized tonic-clonic seizures alone (GTCA), and 80 with focal seizures with secondary generalization (SEC gen).

The median age of onset ranged from 7 years in the GTCA and SEC gen groups to 10 years in the JME group. Age at last follow-up visit ranged from a median of 29 years for GTCA patients, to 35 years for SEC gen patients, to 36 years for JME patients.

Dr. Camfield examined eight social outcomes in each group:

• High school graduation. Subjects with JME fared the best in education. A high school diploma was not achieved by 13% of JME patients, compared with 40% of GTCA and 32% of SEC gen patients.

• Unable to name a single close friend. A quarter of GTCA patients were unable to name a close friend, compared with 9% of JME and 8% of SEC gen patients.

• Unemployment. The groups had similar rates of unemployment (31% JME, 33% GTCA, and 23% SEC gen).

• A psychiatric diagnosis other than attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. SEC gen patients were significantly less likely than were the others to have a psychiatric diagnosis other than ADHD (15% vs. 39% JME and 27% GTCA).

• A criminal conviction. All three groups had similar rates of convictions (4% JME, 7% GTCA, and 4% SEC gen).

• No romantic relationship of more than 3 months. Patients with GTCA were more likely to have never experienced a lasting romantic relationship (24% vs. 17% JME and 14% SEC gen)

• Living alone at the end of follow-up. At the final follow-up, SEC gen patients were significantly less likely to be living alone than were the other groups (8% vs. 30% JME and 23% GTCA).

• Pregnancy outside a stable relationship of more than 6 months. There was some indication of sexual impulsivity in the JME and GTCA groups, Dr. Camfield said. If these patients had become pregnant or caused a pregnancy, it was much more likely to have occurred outside of a stable relationship of at least 6 months’ duration, compared with those in the SEC gen group (79% and 65% vs. 37%).

However, when looking at social outcomes as a whole, there were no significant between-group differences. The majority of each group had at least one of the outcome measures (74% JMW, 76% GTCA, 62% SEC gen). It was not uncommon for patients to have two or more of the outcomes, Dr. Camfield said (22% JME, 21% GTCA, 10% SEC gen).

Remission, defined as being seizure free for at least 5 years and off all antiepileptic drugs, occurred in 40% of the JME group, 75% of the GTCA group, and 81% of the SEC gen group. This clearly indicates that social outcomes remained independent of remission status, Dr. Camfield said.

She had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MONTREAL – Adults who have long-standing epilepsy often have many social difficulties to contend with regardless of whether their childhood seizures have remitted or not, according to a 30-year longitudinal study.

The outcomes of adults who had three different types of childhood epilepsies were "amazingly similar," with high rates of social and romantic isolation, low educational achievement, and psychiatric diagnoses, Dr. Carol Camfield said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

Even those whose seizures had remitted and who were off medication were still likely to have at least one marker of poor social outcome, said Dr. Camfield, a professor of pediatrics at the Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S.

The finding highlights the need for more research into interventions that can address these long-term issues, she said. "They require from all of us prospective interventions in schooling, socialization, employment, and sexuality," she said. "And that’s a lot to ask from a pediatrician."

Her study looked at almost 3 decades of follow-up data on patients included in the Nova Scotia childhood population-based epilepsy cohort. This cohort comprises 692 adults – all the children who were diagnosed with epilepsy in the province in 1977-1985.

From this group, she selected 137 who had epilepsy only, normal intelligence, and a normal neurologic exam. These patients included 23 with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), 34 with generalized tonic-clonic seizures alone (GTCA), and 80 with focal seizures with secondary generalization (SEC gen).

The median age of onset ranged from 7 years in the GTCA and SEC gen groups to 10 years in the JME group. Age at last follow-up visit ranged from a median of 29 years for GTCA patients, to 35 years for SEC gen patients, to 36 years for JME patients.

Dr. Camfield examined eight social outcomes in each group:

• High school graduation. Subjects with JME fared the best in education. A high school diploma was not achieved by 13% of JME patients, compared with 40% of GTCA and 32% of SEC gen patients.

• Unable to name a single close friend. A quarter of GTCA patients were unable to name a close friend, compared with 9% of JME and 8% of SEC gen patients.

• Unemployment. The groups had similar rates of unemployment (31% JME, 33% GTCA, and 23% SEC gen).

• A psychiatric diagnosis other than attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. SEC gen patients were significantly less likely than were the others to have a psychiatric diagnosis other than ADHD (15% vs. 39% JME and 27% GTCA).

• A criminal conviction. All three groups had similar rates of convictions (4% JME, 7% GTCA, and 4% SEC gen).

• No romantic relationship of more than 3 months. Patients with GTCA were more likely to have never experienced a lasting romantic relationship (24% vs. 17% JME and 14% SEC gen)

• Living alone at the end of follow-up. At the final follow-up, SEC gen patients were significantly less likely to be living alone than were the other groups (8% vs. 30% JME and 23% GTCA).

• Pregnancy outside a stable relationship of more than 6 months. There was some indication of sexual impulsivity in the JME and GTCA groups, Dr. Camfield said. If these patients had become pregnant or caused a pregnancy, it was much more likely to have occurred outside of a stable relationship of at least 6 months’ duration, compared with those in the SEC gen group (79% and 65% vs. 37%).

However, when looking at social outcomes as a whole, there were no significant between-group differences. The majority of each group had at least one of the outcome measures (74% JMW, 76% GTCA, 62% SEC gen). It was not uncommon for patients to have two or more of the outcomes, Dr. Camfield said (22% JME, 21% GTCA, 10% SEC gen).

Remission, defined as being seizure free for at least 5 years and off all antiepileptic drugs, occurred in 40% of the JME group, 75% of the GTCA group, and 81% of the SEC gen group. This clearly indicates that social outcomes remained independent of remission status, Dr. Camfield said.

She had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT IEC 2013

Major finding: More than half of adults with childhood generalized epilepsies had at least one problematic social issue.

Data source: The Nova Scotia childhood population-based epilepsy cohort provided almost 30 years’ worth of follow-up data on 137 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Camfield had no financial disclosures.

Structural brain abnormalities predict enduring seizures

MONTREAL – Early imaging may be the best clue about seizure remission in children with early intractable seizures, according to findings from a population-based, retrospective cohort study.

Children who had uncontrolled seizures at 2 years and structural brain abnormalities had a 9% rate of becoming seizure free during a median follow-up period of 12 years. However, 60% of those with structurally normal brains eventually did become seizure free, despite an early history of intractability, Dr. Elaine Wirrell said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"While a significant minority of children with early medical intractability ultimately achieved seizure control without surgery, those with an abnormal imaging study did poorly," said Dr. Wirrell of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. "For this subgroup, early surgical intervention is strongly advised to limit the comorbidities of ongoing, intractable seizures. Conversely, a cautious approach is suggested for those with normal imaging, as most will remit with time."

She and her colleagues examined medical intractability in a group of 381 children who were diagnosed with epilepsy during 1980-2009 and who were followed for a median of 12 years. Of these, 75 (20%) showed early medical intractability, defined as failing at least two antiepileptic medications or continuing to have seizures more often than every 6 months.

The children were a mean of 7 years old when their epilepsy began. Most (75%) had a focal onset, while 23% had a generalized onset. Onset for the remainder was unknown. The etiology was unknown in 54%, genetic in 23%, and structural or metabolic in the remainder.

Overall, 74 children underwent either MRI or CT, and a structural brain abnormality was present in 35. There were 40 children who had structurally normal brains. (One patient was known to have a familial absence syndrome ruling out a structural abnormality and did not undergo brain imaging.)

After a median follow-up of 12 years, 48 patients were still having seizures or had undergone brain surgery; 32 of these initially had abnormal brain imaging. Only three children with a structural brain abnormality were seizure free off or on medications at follow-up. A total of 24 who had normal brain structure eventually became seizure free.

More than half of the patients with an abnormality were surgical candidates because of the presence of a single focal or hemispheric lesion (16), tuberous sclerosis (3), or mesio-temporal sclerosis with periventricular leukomalacia (1). Of 16 who underwent surgery, 7 became seizure free. Five were able to discontinue all antiepileptic drugs.

In a multivariate analysis, neuroimaging was a significant predictor of seizure outcome.

"Imaging that is done properly is important," Dr. Wirrell said in an interview. "There is value with going on with a medication trial, but if one fails, it’s reasonable to have the discussion of possible surgery as we are starting the next."

Dr. Wirrell had no financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Early imaging may be the best clue about seizure remission in children with early intractable seizures, according to findings from a population-based, retrospective cohort study.

Children who had uncontrolled seizures at 2 years and structural brain abnormalities had a 9% rate of becoming seizure free during a median follow-up period of 12 years. However, 60% of those with structurally normal brains eventually did become seizure free, despite an early history of intractability, Dr. Elaine Wirrell said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"While a significant minority of children with early medical intractability ultimately achieved seizure control without surgery, those with an abnormal imaging study did poorly," said Dr. Wirrell of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. "For this subgroup, early surgical intervention is strongly advised to limit the comorbidities of ongoing, intractable seizures. Conversely, a cautious approach is suggested for those with normal imaging, as most will remit with time."

She and her colleagues examined medical intractability in a group of 381 children who were diagnosed with epilepsy during 1980-2009 and who were followed for a median of 12 years. Of these, 75 (20%) showed early medical intractability, defined as failing at least two antiepileptic medications or continuing to have seizures more often than every 6 months.

The children were a mean of 7 years old when their epilepsy began. Most (75%) had a focal onset, while 23% had a generalized onset. Onset for the remainder was unknown. The etiology was unknown in 54%, genetic in 23%, and structural or metabolic in the remainder.

Overall, 74 children underwent either MRI or CT, and a structural brain abnormality was present in 35. There were 40 children who had structurally normal brains. (One patient was known to have a familial absence syndrome ruling out a structural abnormality and did not undergo brain imaging.)

After a median follow-up of 12 years, 48 patients were still having seizures or had undergone brain surgery; 32 of these initially had abnormal brain imaging. Only three children with a structural brain abnormality were seizure free off or on medications at follow-up. A total of 24 who had normal brain structure eventually became seizure free.

More than half of the patients with an abnormality were surgical candidates because of the presence of a single focal or hemispheric lesion (16), tuberous sclerosis (3), or mesio-temporal sclerosis with periventricular leukomalacia (1). Of 16 who underwent surgery, 7 became seizure free. Five were able to discontinue all antiepileptic drugs.

In a multivariate analysis, neuroimaging was a significant predictor of seizure outcome.

"Imaging that is done properly is important," Dr. Wirrell said in an interview. "There is value with going on with a medication trial, but if one fails, it’s reasonable to have the discussion of possible surgery as we are starting the next."

Dr. Wirrell had no financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Early imaging may be the best clue about seizure remission in children with early intractable seizures, according to findings from a population-based, retrospective cohort study.

Children who had uncontrolled seizures at 2 years and structural brain abnormalities had a 9% rate of becoming seizure free during a median follow-up period of 12 years. However, 60% of those with structurally normal brains eventually did become seizure free, despite an early history of intractability, Dr. Elaine Wirrell said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"While a significant minority of children with early medical intractability ultimately achieved seizure control without surgery, those with an abnormal imaging study did poorly," said Dr. Wirrell of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. "For this subgroup, early surgical intervention is strongly advised to limit the comorbidities of ongoing, intractable seizures. Conversely, a cautious approach is suggested for those with normal imaging, as most will remit with time."

She and her colleagues examined medical intractability in a group of 381 children who were diagnosed with epilepsy during 1980-2009 and who were followed for a median of 12 years. Of these, 75 (20%) showed early medical intractability, defined as failing at least two antiepileptic medications or continuing to have seizures more often than every 6 months.

The children were a mean of 7 years old when their epilepsy began. Most (75%) had a focal onset, while 23% had a generalized onset. Onset for the remainder was unknown. The etiology was unknown in 54%, genetic in 23%, and structural or metabolic in the remainder.

Overall, 74 children underwent either MRI or CT, and a structural brain abnormality was present in 35. There were 40 children who had structurally normal brains. (One patient was known to have a familial absence syndrome ruling out a structural abnormality and did not undergo brain imaging.)

After a median follow-up of 12 years, 48 patients were still having seizures or had undergone brain surgery; 32 of these initially had abnormal brain imaging. Only three children with a structural brain abnormality were seizure free off or on medications at follow-up. A total of 24 who had normal brain structure eventually became seizure free.

More than half of the patients with an abnormality were surgical candidates because of the presence of a single focal or hemispheric lesion (16), tuberous sclerosis (3), or mesio-temporal sclerosis with periventricular leukomalacia (1). Of 16 who underwent surgery, 7 became seizure free. Five were able to discontinue all antiepileptic drugs.

In a multivariate analysis, neuroimaging was a significant predictor of seizure outcome.

"Imaging that is done properly is important," Dr. Wirrell said in an interview. "There is value with going on with a medication trial, but if one fails, it’s reasonable to have the discussion of possible surgery as we are starting the next."

Dr. Wirrell had no financial disclosures.

AT IEC 2013

Major finding: Among children with an early history of medically intractable seizures, those with abnormal brain imaging were significantly less likely to become seizure free than were those with normal imaging (9% vs. 60%).

Data source: A population-based, retrospective cohort study of 75 children with early medically intractable epilepsy.

Disclosures: Dr. Elaine Wirrell had no financial disclosures.

Ketamine may help refractory status epilepticus

MONTREAL – Intravenous ketamine resolved refractory convulsive status epilepticus in 14 of 17 cases in a small, uncontrolled prospective study.

In addition to its efficacy, ketamine has a unique safety advantage over more commonly used anesthetics. "It does not cause respiratory depression, so it allows us to avoid intubation and ventilatory support in these children," said Dr. Anna Rosati of the University of Florence (Italy). "Because intubation can worsen the prognosis, we believe ketamine should be considered before conventional anesthetics in children with status epilepticus."

The study examined 17 incidents of convulsive status epilepticus that occurred in 13 children. In 13 cases, first-line treatment with midazolam, propofol, or thiopental had failed. Ketamine was the first-line agent in the other four cases, she reported at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

The children ranged in age from 2 months to 10 years. The mean duration of status epilepticus before ketamine administration was 16 days, with a range of 5 hours to 86 days. Seizure etiology included focal cortical dysplasia (2), other cortical malformations (3), hydrocephalus (1), febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome (2), and Rett syndrome (1). One patient had MELAS syndrome (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes). The etiology was unknown in three.

The ketamine protocol began with two intravenous boluses of 2-3 mg/kg given 5 minutes apart. This was immediately followed by a continuous ketamine infusion, starting at 10 mcg/kg per minute and increasing by 10-mcg increments up to 60 mcg/kg per minute. The mean dosage was 32.5 mcg/kg per minute. Patients also received midazolam as an add-on to prevent emergence reactions. Ketamine was continued for a median of 5 days, with a range of 6 hours to 17 days.

Status epilepticus resolved in 10 of the 13 cases in which ketamine was administered after the first-line drugs had failed and in all 4 cases in which ketamine was the first-line agent. In those four cases, "we were able to avoid intubation," Dr. Rosati said.

The only adverse events noted were hypersalivation, which occurred in all cases, and mild, transient increases in liver enzymes in four cases.

Electroencephalographic changes mirrored clinical improvement, Dr. Rosati said. In the 14 resolved cases, 12 showed a burst suppression pattern and two showed diffuse theta-delta activity. No EEG changes occurred in the three cases without resolution.

Two of the three children who didn’t respond to ketamine had focal cortical dysplasia. Their status resolved after a surgical excision. The third patient had an unknown etiology; status resolved only with a very high thiopental dosage. However, Dr. Rosati noted, a second status episode in that child did resolve with ketamine as a first-line drug.

In light of the small study’s positive results, Dr. Rosati said she is planning to conduct a randomized controlled study of ketamine in status epilepticus.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Intravenous ketamine resolved refractory convulsive status epilepticus in 14 of 17 cases in a small, uncontrolled prospective study.

In addition to its efficacy, ketamine has a unique safety advantage over more commonly used anesthetics. "It does not cause respiratory depression, so it allows us to avoid intubation and ventilatory support in these children," said Dr. Anna Rosati of the University of Florence (Italy). "Because intubation can worsen the prognosis, we believe ketamine should be considered before conventional anesthetics in children with status epilepticus."

The study examined 17 incidents of convulsive status epilepticus that occurred in 13 children. In 13 cases, first-line treatment with midazolam, propofol, or thiopental had failed. Ketamine was the first-line agent in the other four cases, she reported at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

The children ranged in age from 2 months to 10 years. The mean duration of status epilepticus before ketamine administration was 16 days, with a range of 5 hours to 86 days. Seizure etiology included focal cortical dysplasia (2), other cortical malformations (3), hydrocephalus (1), febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome (2), and Rett syndrome (1). One patient had MELAS syndrome (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes). The etiology was unknown in three.

The ketamine protocol began with two intravenous boluses of 2-3 mg/kg given 5 minutes apart. This was immediately followed by a continuous ketamine infusion, starting at 10 mcg/kg per minute and increasing by 10-mcg increments up to 60 mcg/kg per minute. The mean dosage was 32.5 mcg/kg per minute. Patients also received midazolam as an add-on to prevent emergence reactions. Ketamine was continued for a median of 5 days, with a range of 6 hours to 17 days.

Status epilepticus resolved in 10 of the 13 cases in which ketamine was administered after the first-line drugs had failed and in all 4 cases in which ketamine was the first-line agent. In those four cases, "we were able to avoid intubation," Dr. Rosati said.

The only adverse events noted were hypersalivation, which occurred in all cases, and mild, transient increases in liver enzymes in four cases.

Electroencephalographic changes mirrored clinical improvement, Dr. Rosati said. In the 14 resolved cases, 12 showed a burst suppression pattern and two showed diffuse theta-delta activity. No EEG changes occurred in the three cases without resolution.

Two of the three children who didn’t respond to ketamine had focal cortical dysplasia. Their status resolved after a surgical excision. The third patient had an unknown etiology; status resolved only with a very high thiopental dosage. However, Dr. Rosati noted, a second status episode in that child did resolve with ketamine as a first-line drug.

In light of the small study’s positive results, Dr. Rosati said she is planning to conduct a randomized controlled study of ketamine in status epilepticus.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Intravenous ketamine resolved refractory convulsive status epilepticus in 14 of 17 cases in a small, uncontrolled prospective study.

In addition to its efficacy, ketamine has a unique safety advantage over more commonly used anesthetics. "It does not cause respiratory depression, so it allows us to avoid intubation and ventilatory support in these children," said Dr. Anna Rosati of the University of Florence (Italy). "Because intubation can worsen the prognosis, we believe ketamine should be considered before conventional anesthetics in children with status epilepticus."

The study examined 17 incidents of convulsive status epilepticus that occurred in 13 children. In 13 cases, first-line treatment with midazolam, propofol, or thiopental had failed. Ketamine was the first-line agent in the other four cases, she reported at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

The children ranged in age from 2 months to 10 years. The mean duration of status epilepticus before ketamine administration was 16 days, with a range of 5 hours to 86 days. Seizure etiology included focal cortical dysplasia (2), other cortical malformations (3), hydrocephalus (1), febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome (2), and Rett syndrome (1). One patient had MELAS syndrome (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes). The etiology was unknown in three.

The ketamine protocol began with two intravenous boluses of 2-3 mg/kg given 5 minutes apart. This was immediately followed by a continuous ketamine infusion, starting at 10 mcg/kg per minute and increasing by 10-mcg increments up to 60 mcg/kg per minute. The mean dosage was 32.5 mcg/kg per minute. Patients also received midazolam as an add-on to prevent emergence reactions. Ketamine was continued for a median of 5 days, with a range of 6 hours to 17 days.

Status epilepticus resolved in 10 of the 13 cases in which ketamine was administered after the first-line drugs had failed and in all 4 cases in which ketamine was the first-line agent. In those four cases, "we were able to avoid intubation," Dr. Rosati said.

The only adverse events noted were hypersalivation, which occurred in all cases, and mild, transient increases in liver enzymes in four cases.

Electroencephalographic changes mirrored clinical improvement, Dr. Rosati said. In the 14 resolved cases, 12 showed a burst suppression pattern and two showed diffuse theta-delta activity. No EEG changes occurred in the three cases without resolution.

Two of the three children who didn’t respond to ketamine had focal cortical dysplasia. Their status resolved after a surgical excision. The third patient had an unknown etiology; status resolved only with a very high thiopental dosage. However, Dr. Rosati noted, a second status episode in that child did resolve with ketamine as a first-line drug.

In light of the small study’s positive results, Dr. Rosati said she is planning to conduct a randomized controlled study of ketamine in status epilepticus.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT IEC 2013

Major finding: Intravenous ketamine resolved 14 of 17 refractory status epilepticus cases in children.

Data source: A prospective study involving 17 episodes that occurred among 13 children.

Disclosures: Dr. Anna Rosati said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bone growth affected by ketogenic diet in children with epilepsy

MONTREAL – Epilepsy treatment with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months slowed the long-term skeletal development of 29 children who participated in a prospective, longitudinal study.

Children who went on the diet fell behind by a mean of 0.1756 lumbar Z-units every year, compared with children who had normal bone growth, Dr. Mark Mackay said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"Put simply, they accrue bone mass at a slower rate than their age-matched peers," Dr. Mackay of the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, said in an interview.

Children in Dr. Mackay’s study were treated with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months during 2002-2009. They were a mean of 6 years old when they started the diet, and they followed it for a mean of 6 years.

In addition to the high-fat dietary treatment, they received supplements of calcium and vitamin D to reach the minimum daily requirements. They had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans at baseline and every 6 months while on the diet. Normative bone data were used for comparison.

The children also had regular assessment of bone health biomarkers, including serum calcium, potassium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, bone alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and urinary calcium/creatinine ratio.

Children were grouped at baseline according to mobility status on a 5-point scale, ranging from walking without limitations (1) to being transported in a manual wheelchair (5). At baseline, 11 children had a score of 1 or 2, while 18 scored greater than 2.

Before treatment, their mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score was 0.99. Children who had no mobility problems had higher baseline scores than did those with mobility problems (mean, –0.125 vs. –1.18). This was not a surprise, said Dr. Mackay, a pediatric neurologist at Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. "Many of the children we treat have comorbid physical disability, which also places them at risk of poor bone health, due to factors including decreased weight bearing, physical activity, and sunlight exposure, which is important for vitamin D production."

Subjects on the ketogenic diet demonstrated a mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score decrease of 0.1756 units/year. Bone loss was greater in children who had higher baseline Z-scores (–0.28 vs. –0.04 units/year).

Their mean serum alkaline phosphatase levels remained in the normal range throughout the study period. However, the investigators measured elevations in mean osteocalcin (26.5 nmol/L) and mean urinary calcium/creatinine ratio (0.77).

The findings highlight the risks of a ketogenic diet, which relies on fat metabolism to induce ketoacidosis. A neutral pH is necessary to mobilize calcium from bone, Dr. Mackay said.

Children who are on the diet are also at risk for deficiencies in micronutrients important for health, including vitamin D and calcium. The timing of diet initiation also plays an important role, he said.

"Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the normal accrual of bone mass. The bone that is laid down needs to last that person for the rest of their life. Therefore any intervention that affects accrual of bone can have long-lasting health consequences for the child."

While the ketogenic diet is a very effective treatment for some seizure disorders, it’s not risk free, he added. "Some parents see the ketogenic diet as a ‘natural’ alternative to medications, which it is not. Therefore it is important to be improving our knowledge about potential serious long-term side effects so parents can make an informed decision about treatment."

The findings should prompt more study of the diet’s potential long-term impact on skeletal health, Dr. Mackay said. "These will inform development of guidelines for bone surveillance in this high-risk group of predominantly children to minimize potential negative health consequences of the ketogenic diet. ... However, I don’t think we can make any comments at this stage about the role of antiresorptive treatments."

The study was partially funded by Pfizer Australia. Dr. Mackay did not have any financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Epilepsy treatment with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months slowed the long-term skeletal development of 29 children who participated in a prospective, longitudinal study.

Children who went on the diet fell behind by a mean of 0.1756 lumbar Z-units every year, compared with children who had normal bone growth, Dr. Mark Mackay said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"Put simply, they accrue bone mass at a slower rate than their age-matched peers," Dr. Mackay of the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, said in an interview.

Children in Dr. Mackay’s study were treated with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months during 2002-2009. They were a mean of 6 years old when they started the diet, and they followed it for a mean of 6 years.

In addition to the high-fat dietary treatment, they received supplements of calcium and vitamin D to reach the minimum daily requirements. They had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans at baseline and every 6 months while on the diet. Normative bone data were used for comparison.

The children also had regular assessment of bone health biomarkers, including serum calcium, potassium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, bone alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and urinary calcium/creatinine ratio.

Children were grouped at baseline according to mobility status on a 5-point scale, ranging from walking without limitations (1) to being transported in a manual wheelchair (5). At baseline, 11 children had a score of 1 or 2, while 18 scored greater than 2.

Before treatment, their mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score was 0.99. Children who had no mobility problems had higher baseline scores than did those with mobility problems (mean, –0.125 vs. –1.18). This was not a surprise, said Dr. Mackay, a pediatric neurologist at Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. "Many of the children we treat have comorbid physical disability, which also places them at risk of poor bone health, due to factors including decreased weight bearing, physical activity, and sunlight exposure, which is important for vitamin D production."

Subjects on the ketogenic diet demonstrated a mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score decrease of 0.1756 units/year. Bone loss was greater in children who had higher baseline Z-scores (–0.28 vs. –0.04 units/year).

Their mean serum alkaline phosphatase levels remained in the normal range throughout the study period. However, the investigators measured elevations in mean osteocalcin (26.5 nmol/L) and mean urinary calcium/creatinine ratio (0.77).

The findings highlight the risks of a ketogenic diet, which relies on fat metabolism to induce ketoacidosis. A neutral pH is necessary to mobilize calcium from bone, Dr. Mackay said.

Children who are on the diet are also at risk for deficiencies in micronutrients important for health, including vitamin D and calcium. The timing of diet initiation also plays an important role, he said.

"Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the normal accrual of bone mass. The bone that is laid down needs to last that person for the rest of their life. Therefore any intervention that affects accrual of bone can have long-lasting health consequences for the child."

While the ketogenic diet is a very effective treatment for some seizure disorders, it’s not risk free, he added. "Some parents see the ketogenic diet as a ‘natural’ alternative to medications, which it is not. Therefore it is important to be improving our knowledge about potential serious long-term side effects so parents can make an informed decision about treatment."

The findings should prompt more study of the diet’s potential long-term impact on skeletal health, Dr. Mackay said. "These will inform development of guidelines for bone surveillance in this high-risk group of predominantly children to minimize potential negative health consequences of the ketogenic diet. ... However, I don’t think we can make any comments at this stage about the role of antiresorptive treatments."

The study was partially funded by Pfizer Australia. Dr. Mackay did not have any financial disclosures.

MONTREAL – Epilepsy treatment with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months slowed the long-term skeletal development of 29 children who participated in a prospective, longitudinal study.

Children who went on the diet fell behind by a mean of 0.1756 lumbar Z-units every year, compared with children who had normal bone growth, Dr. Mark Mackay said at the 30th International Epilepsy Congress.

"Put simply, they accrue bone mass at a slower rate than their age-matched peers," Dr. Mackay of the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, said in an interview.

Children in Dr. Mackay’s study were treated with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months during 2002-2009. They were a mean of 6 years old when they started the diet, and they followed it for a mean of 6 years.

In addition to the high-fat dietary treatment, they received supplements of calcium and vitamin D to reach the minimum daily requirements. They had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans at baseline and every 6 months while on the diet. Normative bone data were used for comparison.

The children also had regular assessment of bone health biomarkers, including serum calcium, potassium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, bone alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and urinary calcium/creatinine ratio.

Children were grouped at baseline according to mobility status on a 5-point scale, ranging from walking without limitations (1) to being transported in a manual wheelchair (5). At baseline, 11 children had a score of 1 or 2, while 18 scored greater than 2.

Before treatment, their mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score was 0.99. Children who had no mobility problems had higher baseline scores than did those with mobility problems (mean, –0.125 vs. –1.18). This was not a surprise, said Dr. Mackay, a pediatric neurologist at Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. "Many of the children we treat have comorbid physical disability, which also places them at risk of poor bone health, due to factors including decreased weight bearing, physical activity, and sunlight exposure, which is important for vitamin D production."

Subjects on the ketogenic diet demonstrated a mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score decrease of 0.1756 units/year. Bone loss was greater in children who had higher baseline Z-scores (–0.28 vs. –0.04 units/year).

Their mean serum alkaline phosphatase levels remained in the normal range throughout the study period. However, the investigators measured elevations in mean osteocalcin (26.5 nmol/L) and mean urinary calcium/creatinine ratio (0.77).

The findings highlight the risks of a ketogenic diet, which relies on fat metabolism to induce ketoacidosis. A neutral pH is necessary to mobilize calcium from bone, Dr. Mackay said.

Children who are on the diet are also at risk for deficiencies in micronutrients important for health, including vitamin D and calcium. The timing of diet initiation also plays an important role, he said.

"Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the normal accrual of bone mass. The bone that is laid down needs to last that person for the rest of their life. Therefore any intervention that affects accrual of bone can have long-lasting health consequences for the child."

While the ketogenic diet is a very effective treatment for some seizure disorders, it’s not risk free, he added. "Some parents see the ketogenic diet as a ‘natural’ alternative to medications, which it is not. Therefore it is important to be improving our knowledge about potential serious long-term side effects so parents can make an informed decision about treatment."

The findings should prompt more study of the diet’s potential long-term impact on skeletal health, Dr. Mackay said. "These will inform development of guidelines for bone surveillance in this high-risk group of predominantly children to minimize potential negative health consequences of the ketogenic diet. ... However, I don’t think we can make any comments at this stage about the role of antiresorptive treatments."

The study was partially funded by Pfizer Australia. Dr. Mackay did not have any financial disclosures.

AT IEC 2013

Major finding: Participants on the ketogenic diet demonstrated a mean bone mineral density lumbar Z-score decrease of 0.1756 units/year. Bone loss was greater in children who had higher baseline Z-scores (–0.28 vs. –0.04 units/year).

Data source: A prospective, longitudinal study of 29 children who were treated with the ketogenic diet for more than 6 months during 2002-2009.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by Pfizer Australia. Dr. Mackay did not have any financial disclosures.