User login

For MD-IQ use only

Celebrating VA Physicians in Gastroenterology

Last month, I had the privilege of joining more than one hundred physician colleagues in Washington, DC, for AGA Advocacy Day. While standing amidst the majesty of the Capital, I found myself deeply appreciative for those who dedicate their time and energy to public service. Many of these dedicated federal workers choose to be in DC because of a sincere belief in their mission.

Among these mission-driven public servants are federal employees who work in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a member of this group, I come to work energized by the mission to care for those who have served in our military. In my clinical practice, I am reminded regularly of the sacrifices of veterans and their families. This month, and especially on Veterans Day, I hope we will take a moment to express gratitude to veterans for their service to our country.

Many young gastroenterologists may not know that it was the landmark VA Cooperative Study #380, led by Dr. David Lieberman (Portland VA) that helped push Medicare to cover reimbursement for screening colonoscopy. Today, one of the most important ongoing studies in our field – VA Cooperative Study #577 – continues the VA tradition of high-impact health services research. Launched in 2012, the study has enrolled 50,000 veterans to compare FIT and colonoscopy. It is led by Dr. Jason Dominitz (Seattle VA) and Dr. Doug Robertson (White River Junction VA).

Beyond research, VA gastroenterologists play a critical role in training the next generation of clinicians. Over 700 gastroenterologists count the VA as a clinical home, making it the largest GI group practice in the country. Many of us — myself included — were trained or mentored by VA physicians whose dedication to service and science has shaped our careers and the field at large.

This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News has stories about other important contributions to our field. The stories and perspective pieces on Artificial Intelligence are particularly poignant given the announcement last month on the awarding of the Nobel Prize in economics to researchers who study “creative destruction,” the way in which one technological innovation renders others obsolete. Perhaps this award offers another reason to reemphasize and embrace the “art” of medicine.

The views expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Associate Editor

Last month, I had the privilege of joining more than one hundred physician colleagues in Washington, DC, for AGA Advocacy Day. While standing amidst the majesty of the Capital, I found myself deeply appreciative for those who dedicate their time and energy to public service. Many of these dedicated federal workers choose to be in DC because of a sincere belief in their mission.

Among these mission-driven public servants are federal employees who work in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a member of this group, I come to work energized by the mission to care for those who have served in our military. In my clinical practice, I am reminded regularly of the sacrifices of veterans and their families. This month, and especially on Veterans Day, I hope we will take a moment to express gratitude to veterans for their service to our country.

Many young gastroenterologists may not know that it was the landmark VA Cooperative Study #380, led by Dr. David Lieberman (Portland VA) that helped push Medicare to cover reimbursement for screening colonoscopy. Today, one of the most important ongoing studies in our field – VA Cooperative Study #577 – continues the VA tradition of high-impact health services research. Launched in 2012, the study has enrolled 50,000 veterans to compare FIT and colonoscopy. It is led by Dr. Jason Dominitz (Seattle VA) and Dr. Doug Robertson (White River Junction VA).

Beyond research, VA gastroenterologists play a critical role in training the next generation of clinicians. Over 700 gastroenterologists count the VA as a clinical home, making it the largest GI group practice in the country. Many of us — myself included — were trained or mentored by VA physicians whose dedication to service and science has shaped our careers and the field at large.

This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News has stories about other important contributions to our field. The stories and perspective pieces on Artificial Intelligence are particularly poignant given the announcement last month on the awarding of the Nobel Prize in economics to researchers who study “creative destruction,” the way in which one technological innovation renders others obsolete. Perhaps this award offers another reason to reemphasize and embrace the “art” of medicine.

The views expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Associate Editor

Last month, I had the privilege of joining more than one hundred physician colleagues in Washington, DC, for AGA Advocacy Day. While standing amidst the majesty of the Capital, I found myself deeply appreciative for those who dedicate their time and energy to public service. Many of these dedicated federal workers choose to be in DC because of a sincere belief in their mission.

Among these mission-driven public servants are federal employees who work in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a member of this group, I come to work energized by the mission to care for those who have served in our military. In my clinical practice, I am reminded regularly of the sacrifices of veterans and their families. This month, and especially on Veterans Day, I hope we will take a moment to express gratitude to veterans for their service to our country.

Many young gastroenterologists may not know that it was the landmark VA Cooperative Study #380, led by Dr. David Lieberman (Portland VA) that helped push Medicare to cover reimbursement for screening colonoscopy. Today, one of the most important ongoing studies in our field – VA Cooperative Study #577 – continues the VA tradition of high-impact health services research. Launched in 2012, the study has enrolled 50,000 veterans to compare FIT and colonoscopy. It is led by Dr. Jason Dominitz (Seattle VA) and Dr. Doug Robertson (White River Junction VA).

Beyond research, VA gastroenterologists play a critical role in training the next generation of clinicians. Over 700 gastroenterologists count the VA as a clinical home, making it the largest GI group practice in the country. Many of us — myself included — were trained or mentored by VA physicians whose dedication to service and science has shaped our careers and the field at large.

This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News has stories about other important contributions to our field. The stories and perspective pieces on Artificial Intelligence are particularly poignant given the announcement last month on the awarding of the Nobel Prize in economics to researchers who study “creative destruction,” the way in which one technological innovation renders others obsolete. Perhaps this award offers another reason to reemphasize and embrace the “art” of medicine.

The views expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Associate Editor

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

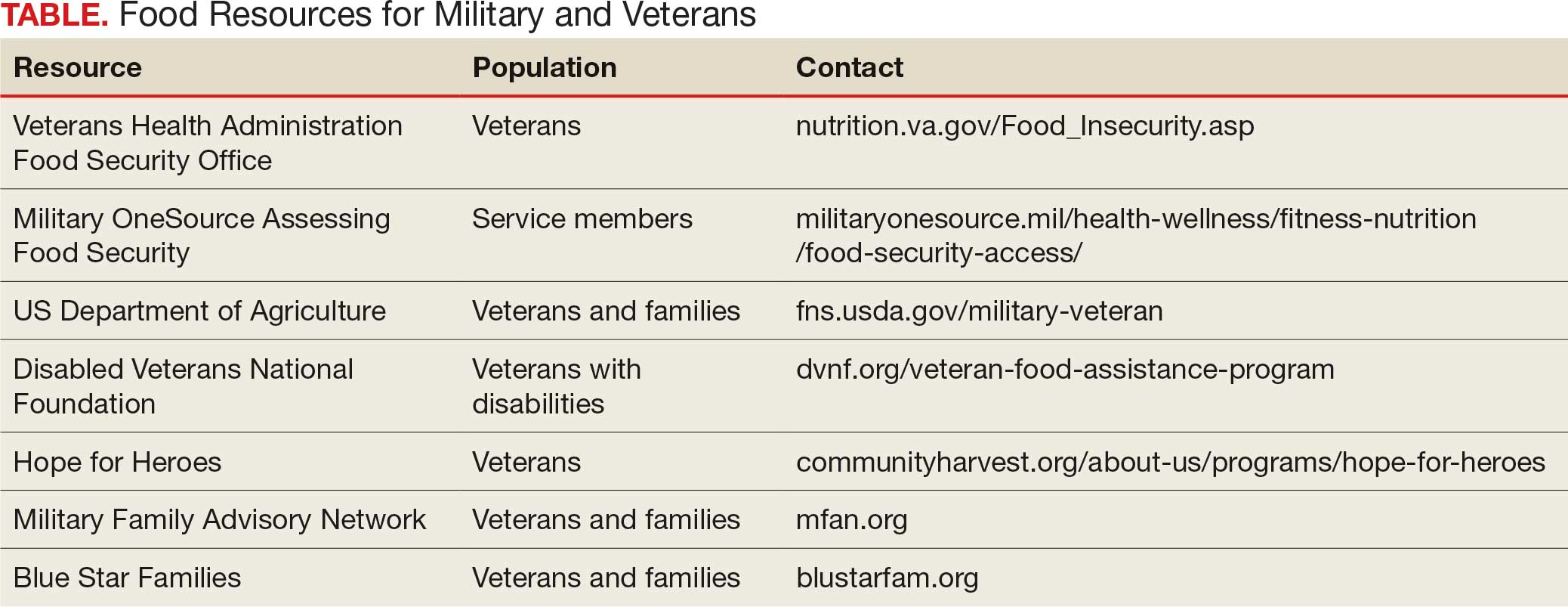

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

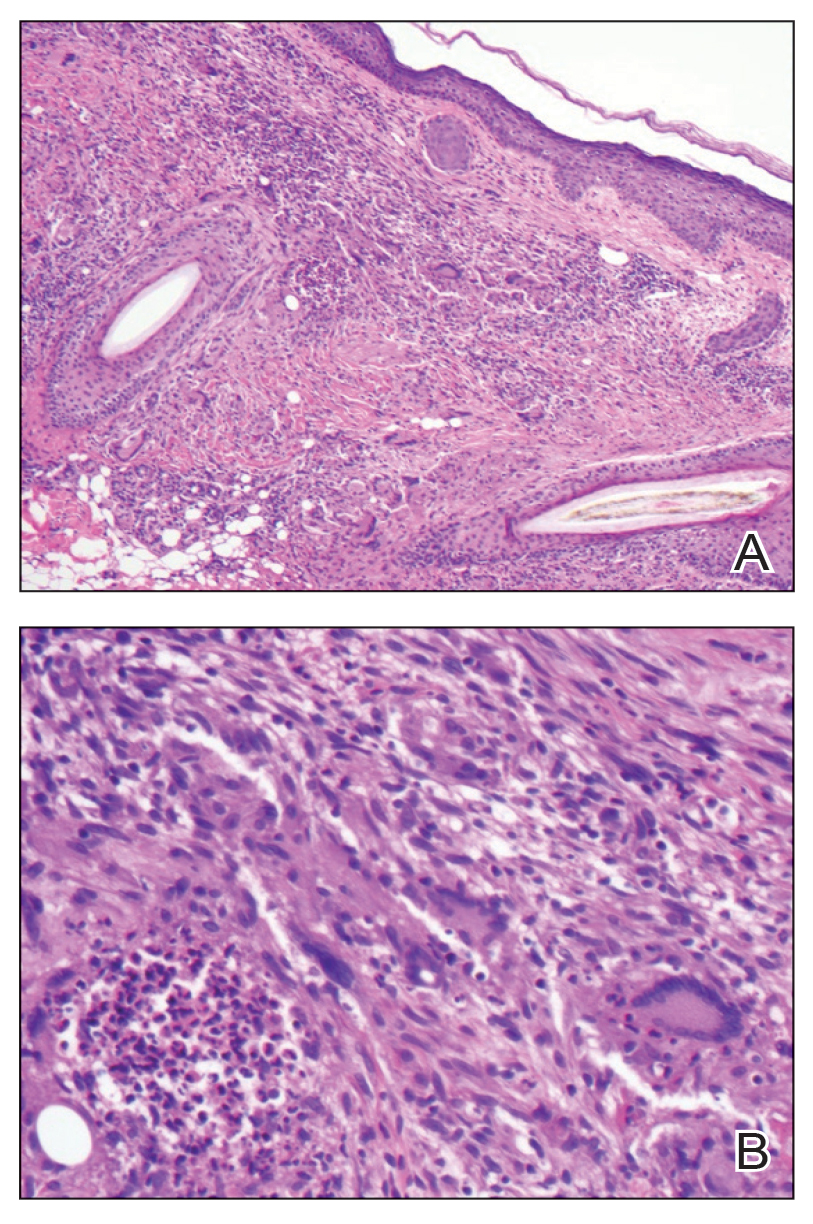

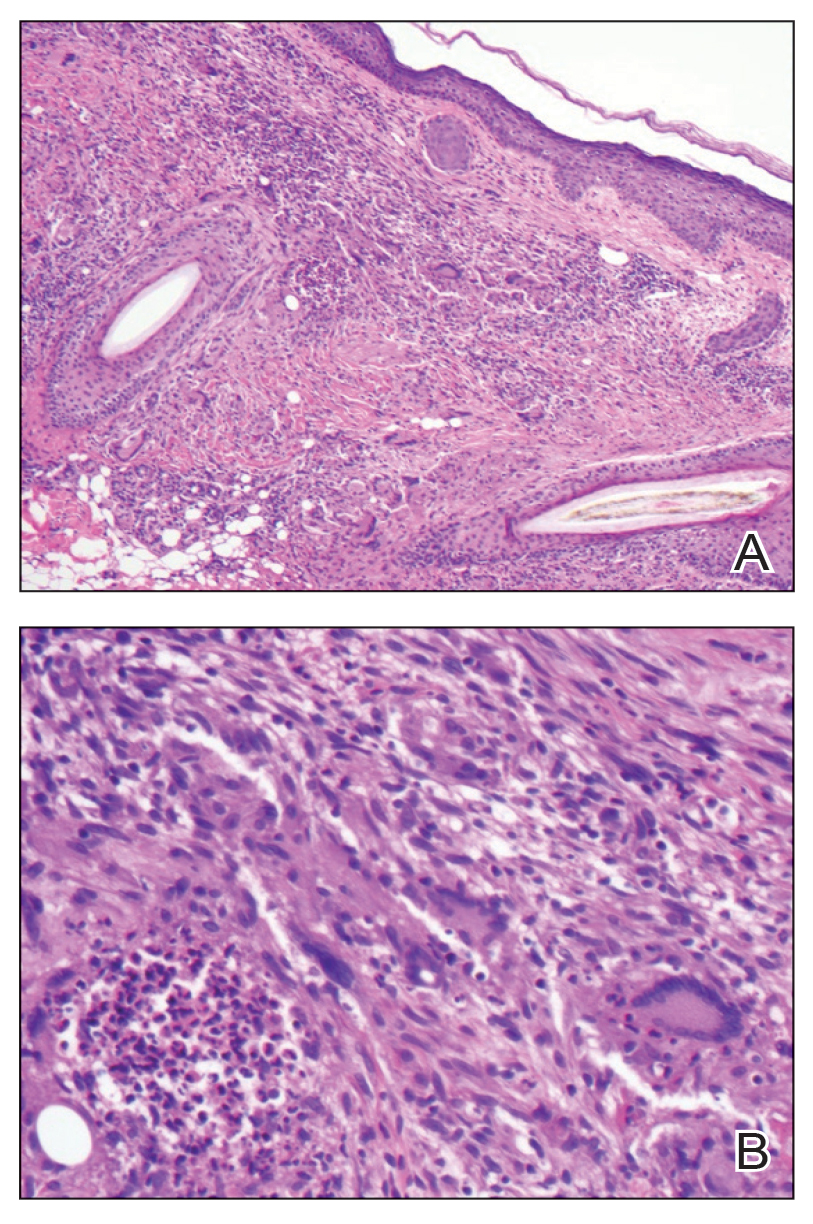

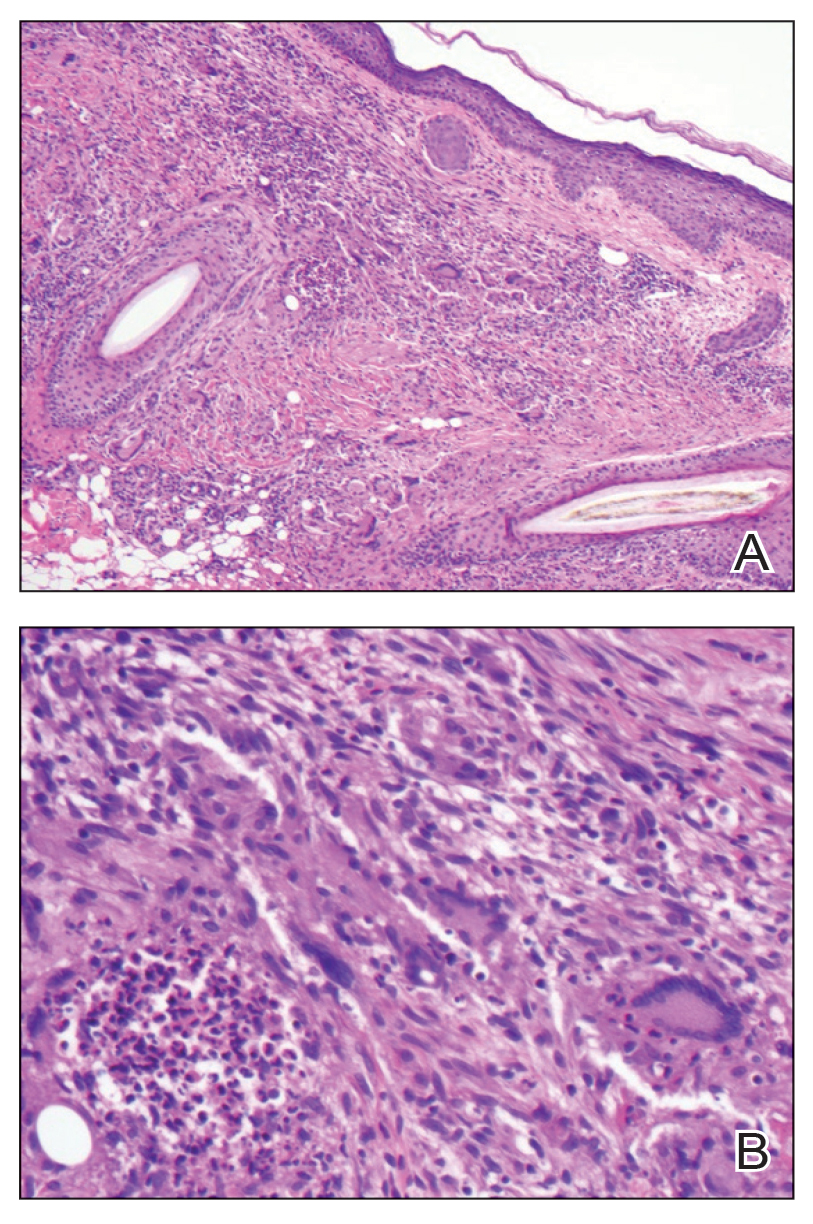

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

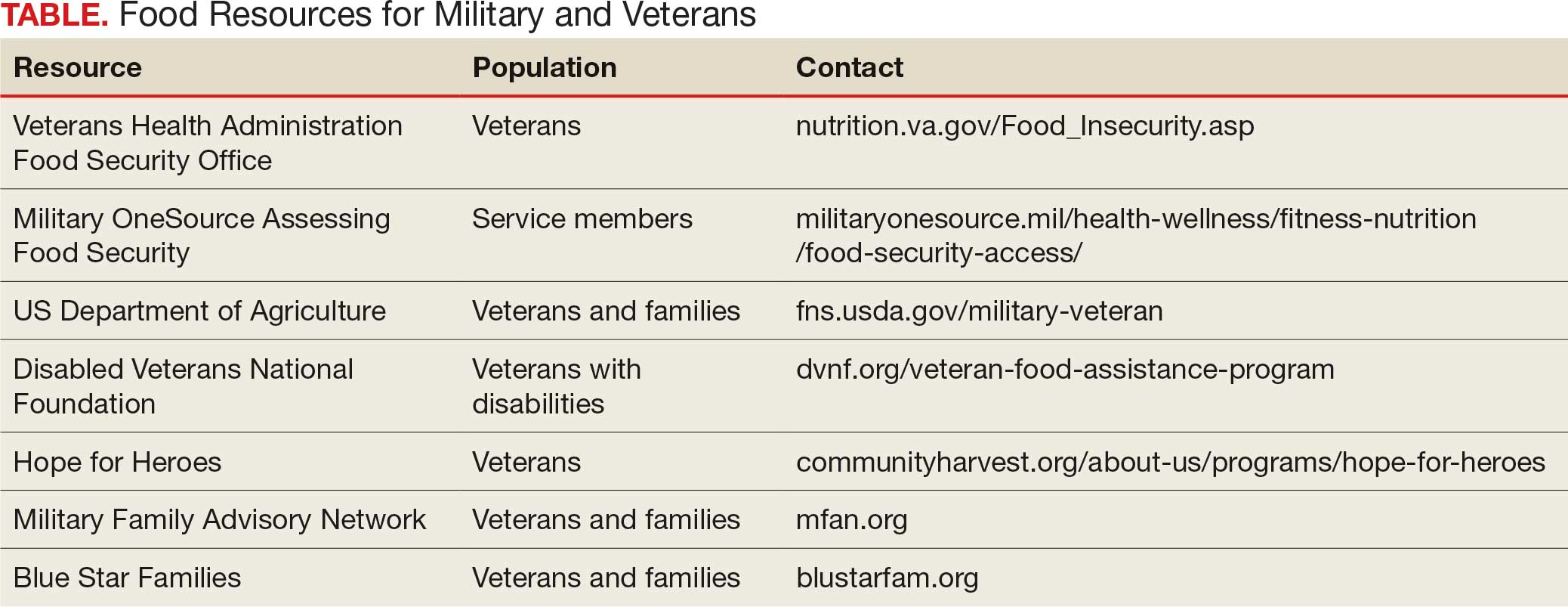

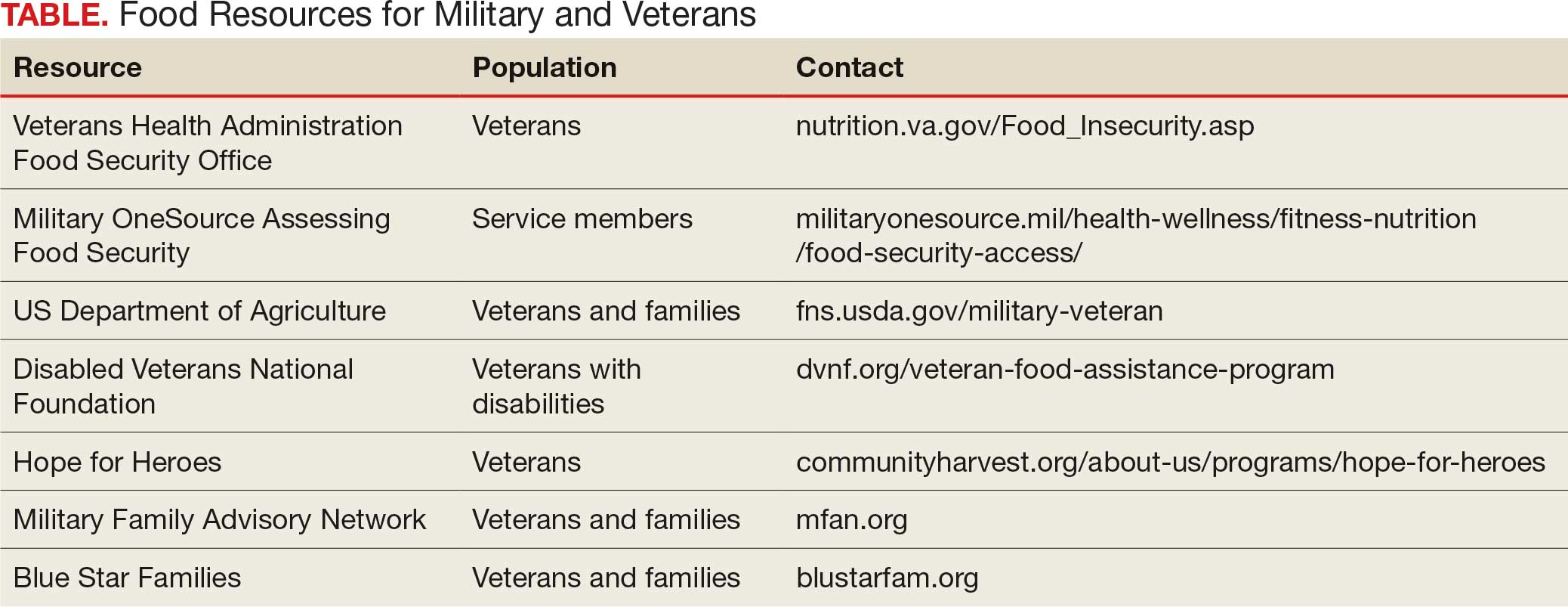

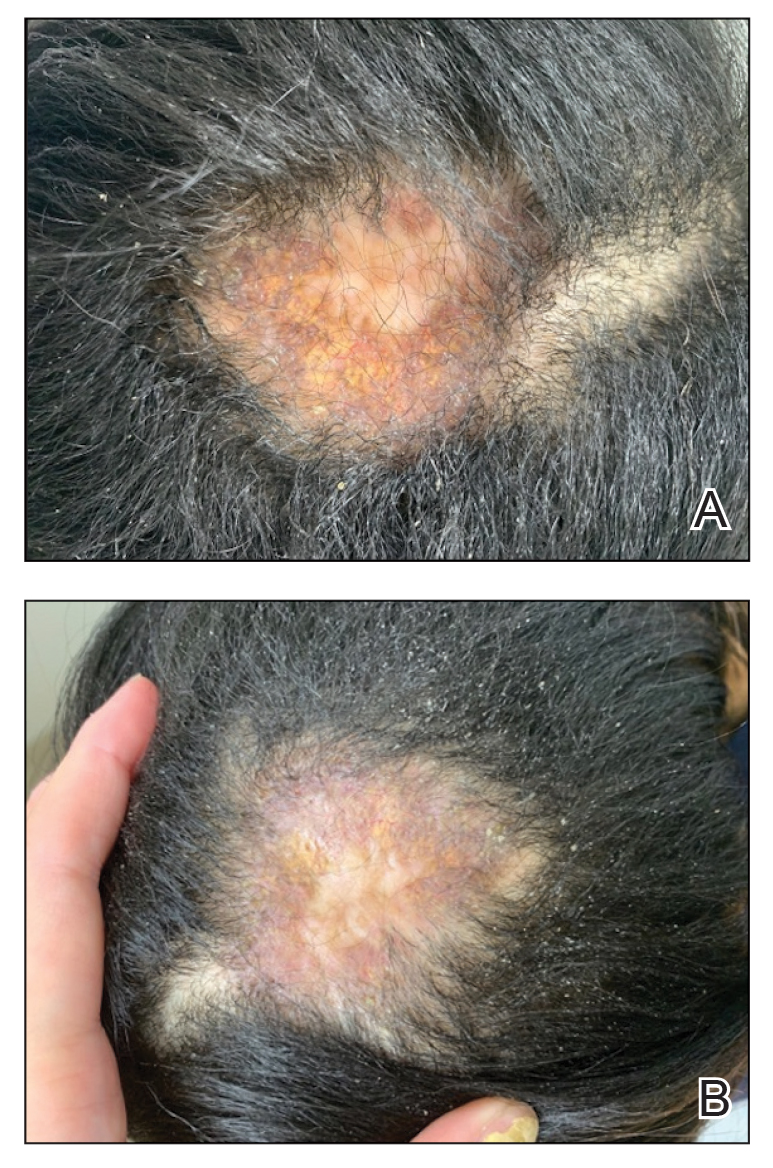

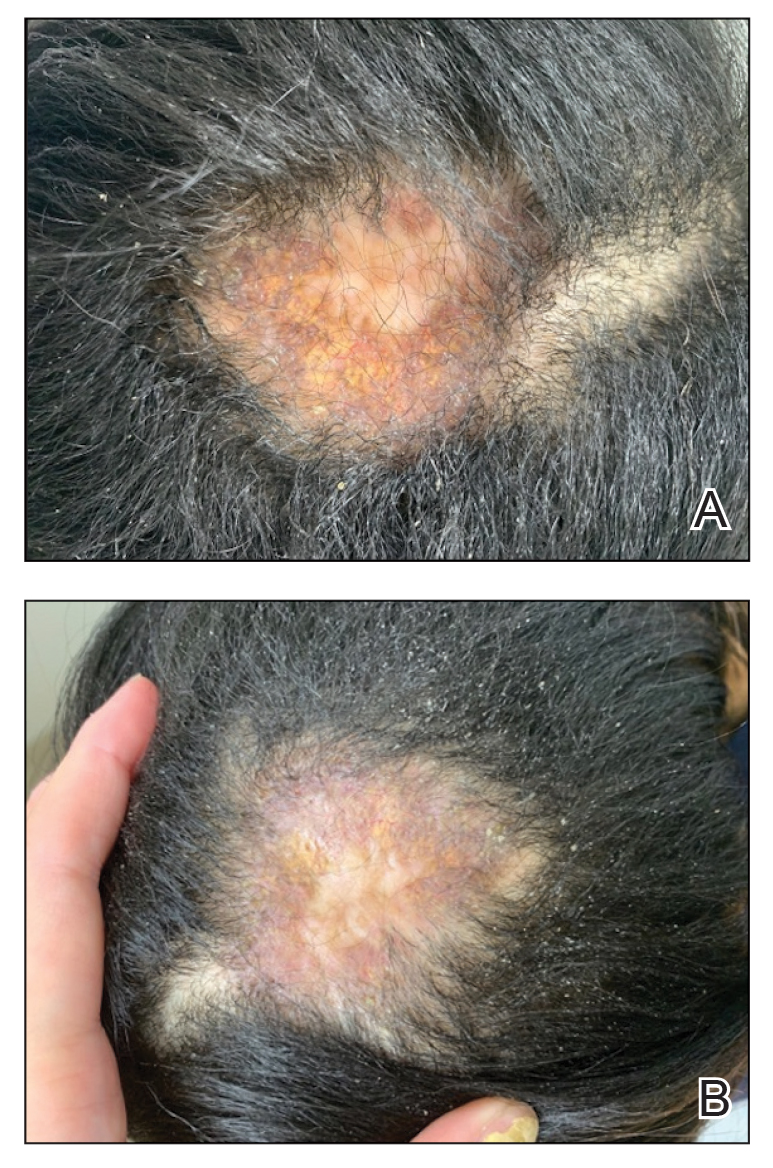

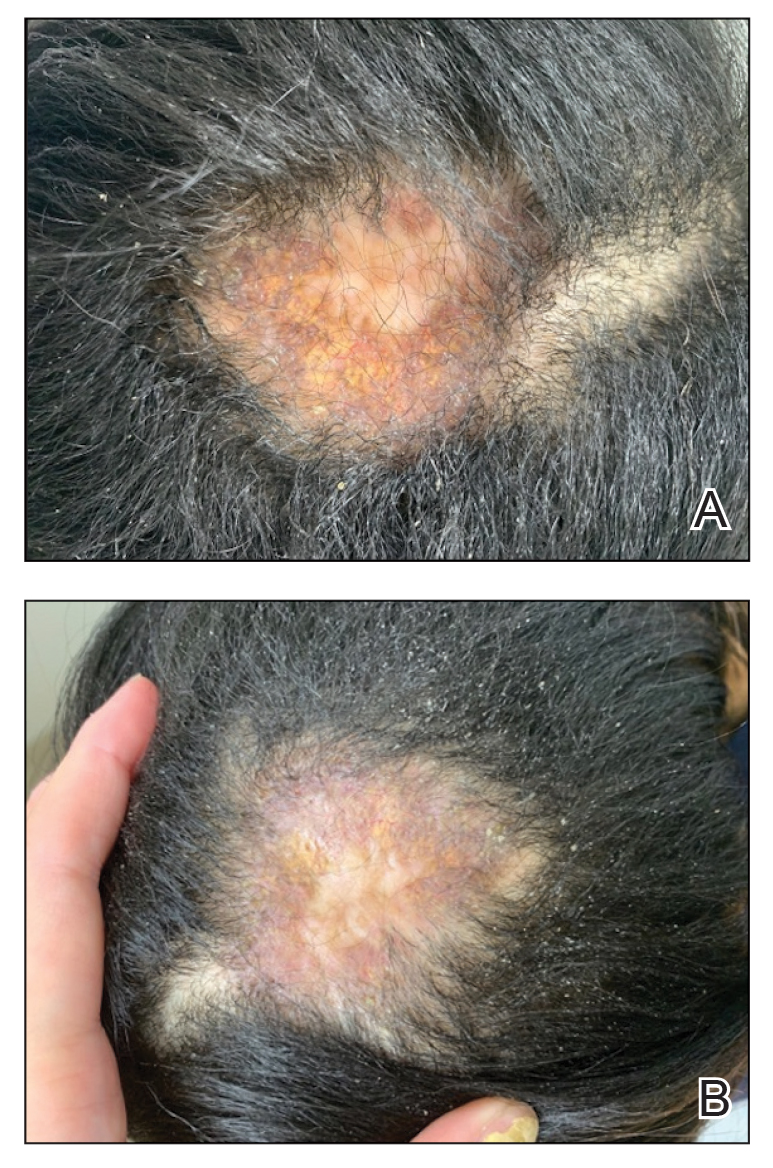

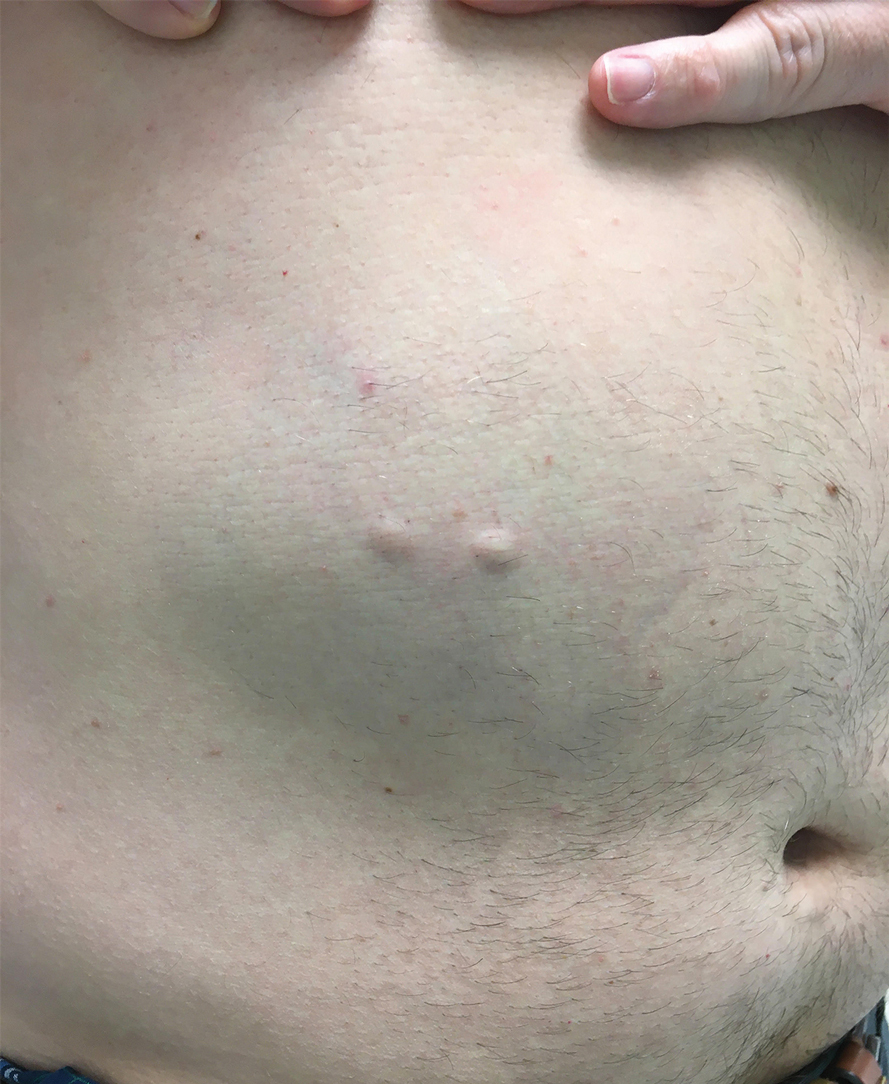

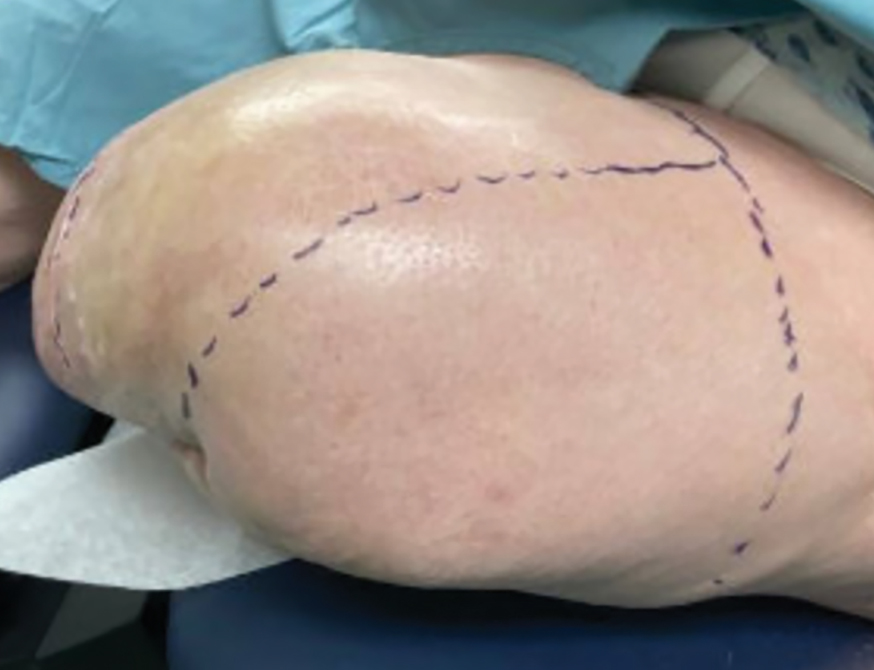

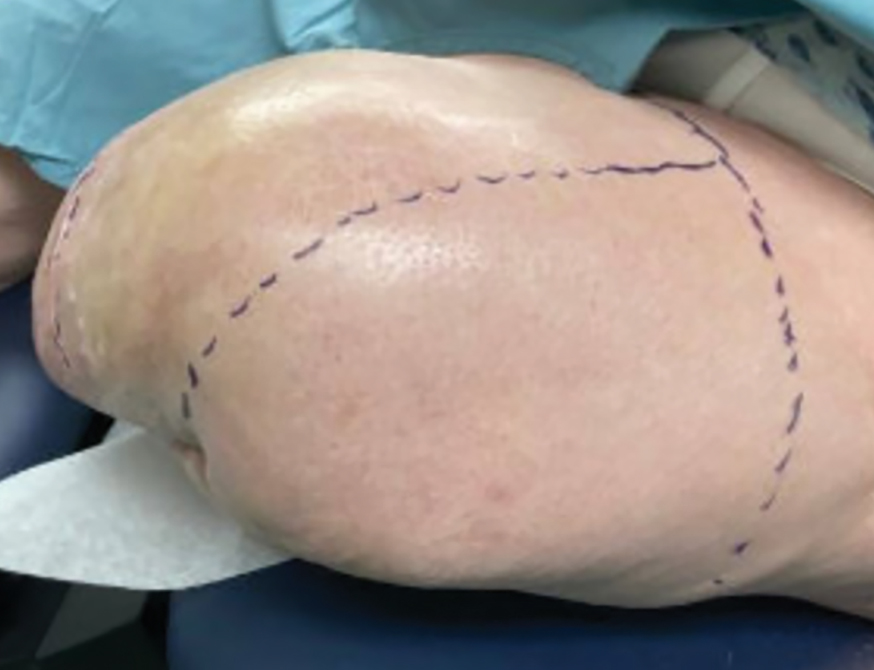

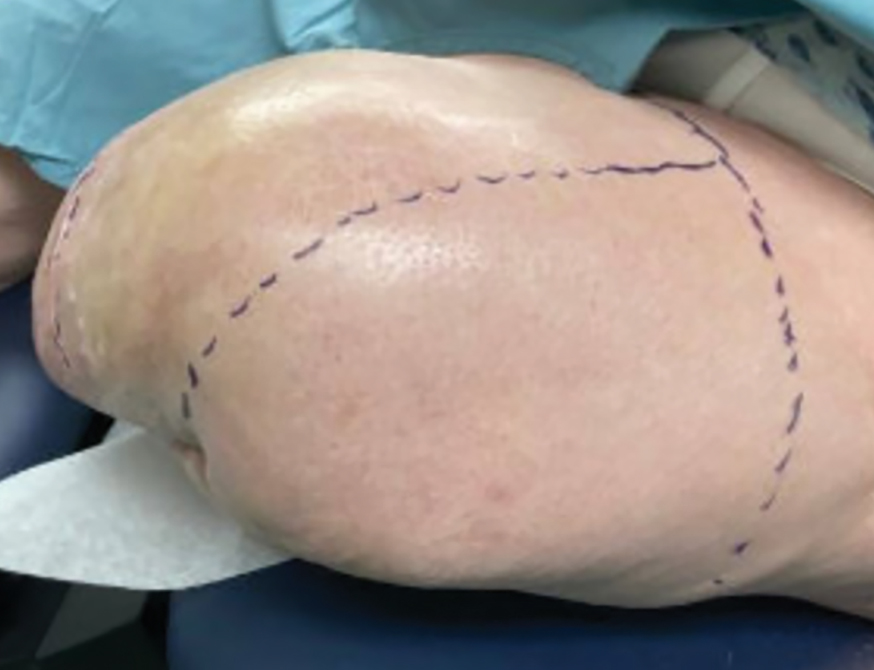

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

PRACTICE POINTS

- In skin of color, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma can appear orange or brown compared to its yellow appearance in lighter skin types.

- When necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is suspected, a thorough malignancy workup should be conducted.

Racial, Ethnic Discrimination Tied to Psychosis Risk

TOPLINE:

Racial and ethnic discrimination was consistently associated with increased risk for psychosis in studies included in a new umbrella review, with odds nearly doubled for both psychotic symptoms and experiences.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers searched 5 databases and then conducted an umbrella review of 7 systematic reviews, 4 of which included meta-analyses, published between 2003 and 2023.

- The systematic reviews included 23 primary studies representing more than 40,000 participants from Europe and the US.

- Investigators assessed the potential association between perceived racial or ethnic discrimination (mostly measured using self-reported questionnaires) and risk for psychosis (measured using established questionnaires).

- They assessed the risk for bias using the 16-item A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews, version 2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist.

TAKEAWAY:

- All reviews that included meta-analyses showed significant associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and psychotic symptoms (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.3-2.5) and psychotic experiences (pooled OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7).

- Perceived racial or ethnic discrimination was also strongly linked to delusional symptoms (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.6-4.0) and hallucinatory symptoms (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1).

- The largest of the included studies showed a dose-response relationship between higher levels of lifetime perceived racial or ethnic discrimination and greater likelihood of psychotic experiences.

- More robust associations were found in nonclinical populations compared to clinical ones, but there were significant associations in both.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our review was only looking at the impact of a person directly perceiving racism or interpersonal racial or ethnic discrimination; it may be that systemic racism, which can go unseen but still have profound impacts, could further contribute to mental health disparities,” lead investigator India Francis-Crossley, University College London, London, UK, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in PLOS Mental Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The evidence was primarily based on cross-sectional studies and was limited by high heterogeneity. The reviews included showed low or critically low AMSTAR-2 quality scores, which may have affected the robustness of the findings. More robust evidence was observed for psychotic outcomes in nonclinical populations compared to clinical samples. Additionally, the study potentially exacerbated errors or misreporting in the original reviews and did not include relevant structural factors such as income, education, housing, and poverty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the University College London-Windsor Fellowship Research Opportunities scholarship, Wellcome Trust PhD Fellowship in Mental Health Science, Mental Health Mission Early Psychosis Workstream, and UK Research and Innovation funding for the Population Mental Health Consortium. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Racial and ethnic discrimination was consistently associated with increased risk for psychosis in studies included in a new umbrella review, with odds nearly doubled for both psychotic symptoms and experiences.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers searched 5 databases and then conducted an umbrella review of 7 systematic reviews, 4 of which included meta-analyses, published between 2003 and 2023.

- The systematic reviews included 23 primary studies representing more than 40,000 participants from Europe and the US.

- Investigators assessed the potential association between perceived racial or ethnic discrimination (mostly measured using self-reported questionnaires) and risk for psychosis (measured using established questionnaires).

- They assessed the risk for bias using the 16-item A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews, version 2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist.

TAKEAWAY:

- All reviews that included meta-analyses showed significant associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and psychotic symptoms (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.3-2.5) and psychotic experiences (pooled OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7).

- Perceived racial or ethnic discrimination was also strongly linked to delusional symptoms (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.6-4.0) and hallucinatory symptoms (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1).

- The largest of the included studies showed a dose-response relationship between higher levels of lifetime perceived racial or ethnic discrimination and greater likelihood of psychotic experiences.

- More robust associations were found in nonclinical populations compared to clinical ones, but there were significant associations in both.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our review was only looking at the impact of a person directly perceiving racism or interpersonal racial or ethnic discrimination; it may be that systemic racism, which can go unseen but still have profound impacts, could further contribute to mental health disparities,” lead investigator India Francis-Crossley, University College London, London, UK, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in PLOS Mental Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The evidence was primarily based on cross-sectional studies and was limited by high heterogeneity. The reviews included showed low or critically low AMSTAR-2 quality scores, which may have affected the robustness of the findings. More robust evidence was observed for psychotic outcomes in nonclinical populations compared to clinical samples. Additionally, the study potentially exacerbated errors or misreporting in the original reviews and did not include relevant structural factors such as income, education, housing, and poverty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the University College London-Windsor Fellowship Research Opportunities scholarship, Wellcome Trust PhD Fellowship in Mental Health Science, Mental Health Mission Early Psychosis Workstream, and UK Research and Innovation funding for the Population Mental Health Consortium. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Racial and ethnic discrimination was consistently associated with increased risk for psychosis in studies included in a new umbrella review, with odds nearly doubled for both psychotic symptoms and experiences.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers searched 5 databases and then conducted an umbrella review of 7 systematic reviews, 4 of which included meta-analyses, published between 2003 and 2023.

- The systematic reviews included 23 primary studies representing more than 40,000 participants from Europe and the US.

- Investigators assessed the potential association between perceived racial or ethnic discrimination (mostly measured using self-reported questionnaires) and risk for psychosis (measured using established questionnaires).

- They assessed the risk for bias using the 16-item A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews, version 2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist.

TAKEAWAY:

- All reviews that included meta-analyses showed significant associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and psychotic symptoms (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.3-2.5) and psychotic experiences (pooled OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7).

- Perceived racial or ethnic discrimination was also strongly linked to delusional symptoms (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.6-4.0) and hallucinatory symptoms (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1).

- The largest of the included studies showed a dose-response relationship between higher levels of lifetime perceived racial or ethnic discrimination and greater likelihood of psychotic experiences.

- More robust associations were found in nonclinical populations compared to clinical ones, but there were significant associations in both.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our review was only looking at the impact of a person directly perceiving racism or interpersonal racial or ethnic discrimination; it may be that systemic racism, which can go unseen but still have profound impacts, could further contribute to mental health disparities,” lead investigator India Francis-Crossley, University College London, London, UK, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in PLOS Mental Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The evidence was primarily based on cross-sectional studies and was limited by high heterogeneity. The reviews included showed low or critically low AMSTAR-2 quality scores, which may have affected the robustness of the findings. More robust evidence was observed for psychotic outcomes in nonclinical populations compared to clinical samples. Additionally, the study potentially exacerbated errors or misreporting in the original reviews and did not include relevant structural factors such as income, education, housing, and poverty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the University College London-Windsor Fellowship Research Opportunities scholarship, Wellcome Trust PhD Fellowship in Mental Health Science, Mental Health Mission Early Psychosis Workstream, and UK Research and Innovation funding for the Population Mental Health Consortium. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parental Mental Disorders May Double Offspring Mortality Risk

TOPLINE:

Offspring of parents with mental disorders had nearly double the risk for mortality, especially from unnatural causes, compared to those with parents did not have a mental disorder, a new Swedish cohort study showed. Additionally, mortality risk was highest when both parents had mental disorders but was not affected by the sex of the affected parent.

METHODOLOGY:

- A nationwide register-based cohort study in Sweden included more than 3.5 million individuals born between 1973 and 2014 (51% men); 35% had a parent with a mental disorder (13% paternal, 16% maternal, and 6% both parents).

- Mental disorder categories included alcohol or substance use, psychotic, mood, anxiety or stress-related, eating, and personality disorders and intellectual disability. Exposure timing was classified by offspring age (mean age, 15.8 years) at parental diagnosis.

- Participants were followed up from birth until death, the death of either parent, emigration (up to 2014), either parent’s emigration, or the end of 2023, whichever came first (median follow-up duration, 20.1 years).

- The main outcome was all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes were deaths from natural and unnatural causes, as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease, cancer, suicide, and unintentional injuries. Cousin comparison analyses were also conducted to account for confounding.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up, offspring exposed to parental psychiatric disorders had higher overall mortality rates than unexposed offspring (7.9 vs 3.55 per 10,000 person-years). Mortality rates due to natural causes were 4.0 vs 2.4 per 10,000 person-years and were 3.95 vs 1.1 per 10,000 person-years for mortality due to unnatural causes.

- Exposed offspring had an increased risk for mortality due to any cause (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.1), natural causes (aHR, 1.9), and unnatural causes (aHR, 2.45). Exposure was also associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular and cancer-related death, suicide, and death due to unintentional injuries. The associations remained significant, although slightly attenuated, in cousin comparison analyses.

- The highest risks for mortality were in offspring exposed at ages 1-2 years to both parents having mental disorders (HR for natural causes, 4.5; HR for unnatural causes, 5.3).

- The risk varied by the type of parental mental disorder, with HRs ranging from 1.6 for eating disorders to 2.2 for intellectual disability.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings highlight the need for improved surveillance, prevention, and early detection strategies to reduce the risk of premature mortality among offspring exposed to parental mental disorders. Whether additional support for families affected by mental disorders could mitigate the risk warrants further investigation,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hui Wang, PhD, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

Reliance on registry data may have led to the misclassification of parental mental disorders. The study lacked data on genetic factors, parenting quality, cohabitation, and social support, and its generalizability may have been limited. Immigration data after 2014 were unavailable, potentially leading to misclassifications of exposure and outcomes. The Patient Register did not distinguish between diagnoses made in general vs psychiatric hospital settings, and cousin comparisons remained susceptible to bias from unmeasured confounding and may have been limited in capturing temporal and familial heterogeneity.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare and the Heart and Lung Foundation. Wang reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other investigator reported receiving grants from Forte and the Heart and Lung Foundation.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Offspring of parents with mental disorders had nearly double the risk for mortality, especially from unnatural causes, compared to those with parents did not have a mental disorder, a new Swedish cohort study showed. Additionally, mortality risk was highest when both parents had mental disorders but was not affected by the sex of the affected parent.

METHODOLOGY:

- A nationwide register-based cohort study in Sweden included more than 3.5 million individuals born between 1973 and 2014 (51% men); 35% had a parent with a mental disorder (13% paternal, 16% maternal, and 6% both parents).

- Mental disorder categories included alcohol or substance use, psychotic, mood, anxiety or stress-related, eating, and personality disorders and intellectual disability. Exposure timing was classified by offspring age (mean age, 15.8 years) at parental diagnosis.

- Participants were followed up from birth until death, the death of either parent, emigration (up to 2014), either parent’s emigration, or the end of 2023, whichever came first (median follow-up duration, 20.1 years).

- The main outcome was all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes were deaths from natural and unnatural causes, as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease, cancer, suicide, and unintentional injuries. Cousin comparison analyses were also conducted to account for confounding.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up, offspring exposed to parental psychiatric disorders had higher overall mortality rates than unexposed offspring (7.9 vs 3.55 per 10,000 person-years). Mortality rates due to natural causes were 4.0 vs 2.4 per 10,000 person-years and were 3.95 vs 1.1 per 10,000 person-years for mortality due to unnatural causes.

- Exposed offspring had an increased risk for mortality due to any cause (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.1), natural causes (aHR, 1.9), and unnatural causes (aHR, 2.45). Exposure was also associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular and cancer-related death, suicide, and death due to unintentional injuries. The associations remained significant, although slightly attenuated, in cousin comparison analyses.

- The highest risks for mortality were in offspring exposed at ages 1-2 years to both parents having mental disorders (HR for natural causes, 4.5; HR for unnatural causes, 5.3).

- The risk varied by the type of parental mental disorder, with HRs ranging from 1.6 for eating disorders to 2.2 for intellectual disability.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings highlight the need for improved surveillance, prevention, and early detection strategies to reduce the risk of premature mortality among offspring exposed to parental mental disorders. Whether additional support for families affected by mental disorders could mitigate the risk warrants further investigation,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hui Wang, PhD, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

Reliance on registry data may have led to the misclassification of parental mental disorders. The study lacked data on genetic factors, parenting quality, cohabitation, and social support, and its generalizability may have been limited. Immigration data after 2014 were unavailable, potentially leading to misclassifications of exposure and outcomes. The Patient Register did not distinguish between diagnoses made in general vs psychiatric hospital settings, and cousin comparisons remained susceptible to bias from unmeasured confounding and may have been limited in capturing temporal and familial heterogeneity.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare and the Heart and Lung Foundation. Wang reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other investigator reported receiving grants from Forte and the Heart and Lung Foundation.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Offspring of parents with mental disorders had nearly double the risk for mortality, especially from unnatural causes, compared to those with parents did not have a mental disorder, a new Swedish cohort study showed. Additionally, mortality risk was highest when both parents had mental disorders but was not affected by the sex of the affected parent.

METHODOLOGY:

- A nationwide register-based cohort study in Sweden included more than 3.5 million individuals born between 1973 and 2014 (51% men); 35% had a parent with a mental disorder (13% paternal, 16% maternal, and 6% both parents).

- Mental disorder categories included alcohol or substance use, psychotic, mood, anxiety or stress-related, eating, and personality disorders and intellectual disability. Exposure timing was classified by offspring age (mean age, 15.8 years) at parental diagnosis.

- Participants were followed up from birth until death, the death of either parent, emigration (up to 2014), either parent’s emigration, or the end of 2023, whichever came first (median follow-up duration, 20.1 years).

- The main outcome was all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes were deaths from natural and unnatural causes, as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease, cancer, suicide, and unintentional injuries. Cousin comparison analyses were also conducted to account for confounding.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up, offspring exposed to parental psychiatric disorders had higher overall mortality rates than unexposed offspring (7.9 vs 3.55 per 10,000 person-years). Mortality rates due to natural causes were 4.0 vs 2.4 per 10,000 person-years and were 3.95 vs 1.1 per 10,000 person-years for mortality due to unnatural causes.

- Exposed offspring had an increased risk for mortality due to any cause (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.1), natural causes (aHR, 1.9), and unnatural causes (aHR, 2.45). Exposure was also associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular and cancer-related death, suicide, and death due to unintentional injuries. The associations remained significant, although slightly attenuated, in cousin comparison analyses.

- The highest risks for mortality were in offspring exposed at ages 1-2 years to both parents having mental disorders (HR for natural causes, 4.5; HR for unnatural causes, 5.3).

- The risk varied by the type of parental mental disorder, with HRs ranging from 1.6 for eating disorders to 2.2 for intellectual disability.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings highlight the need for improved surveillance, prevention, and early detection strategies to reduce the risk of premature mortality among offspring exposed to parental mental disorders. Whether additional support for families affected by mental disorders could mitigate the risk warrants further investigation,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hui Wang, PhD, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

Reliance on registry data may have led to the misclassification of parental mental disorders. The study lacked data on genetic factors, parenting quality, cohabitation, and social support, and its generalizability may have been limited. Immigration data after 2014 were unavailable, potentially leading to misclassifications of exposure and outcomes. The Patient Register did not distinguish between diagnoses made in general vs psychiatric hospital settings, and cousin comparisons remained susceptible to bias from unmeasured confounding and may have been limited in capturing temporal and familial heterogeneity.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare and the Heart and Lung Foundation. Wang reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other investigator reported receiving grants from Forte and the Heart and Lung Foundation.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

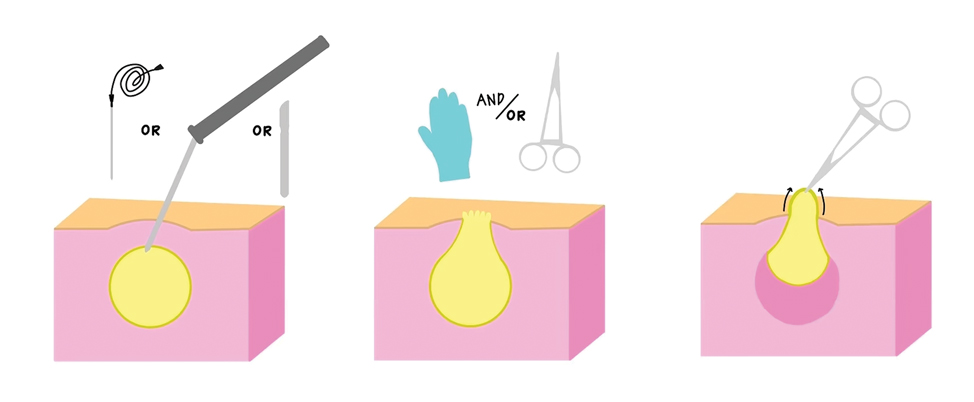

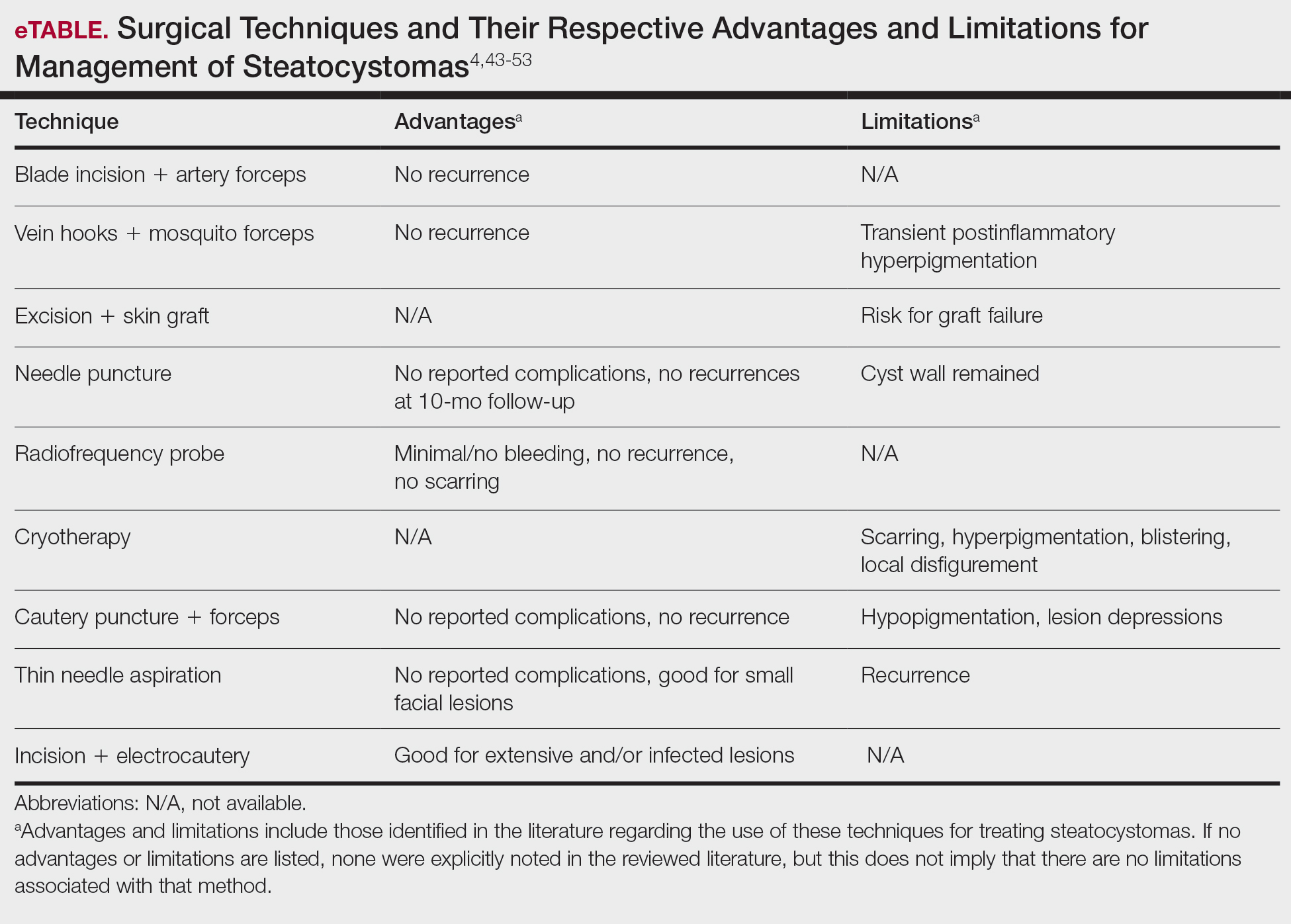

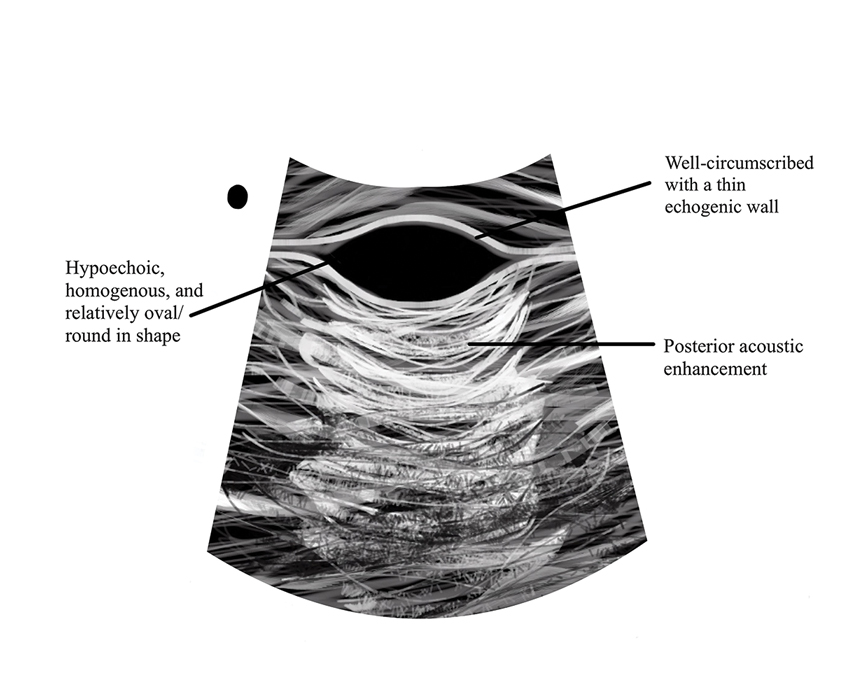

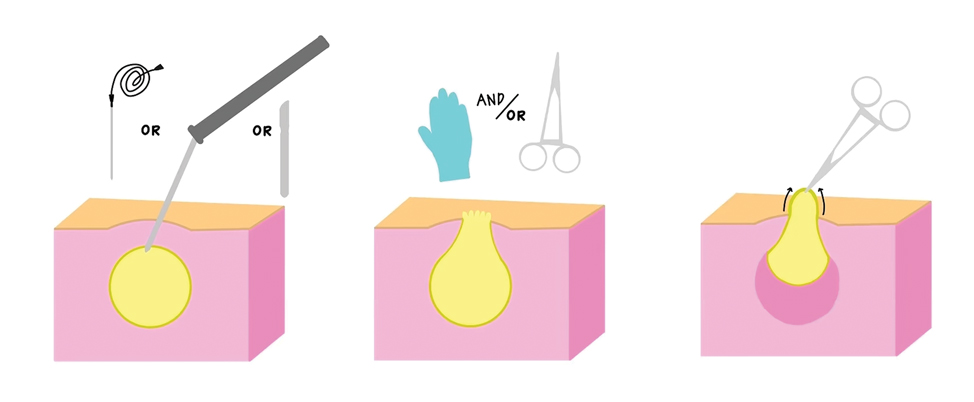

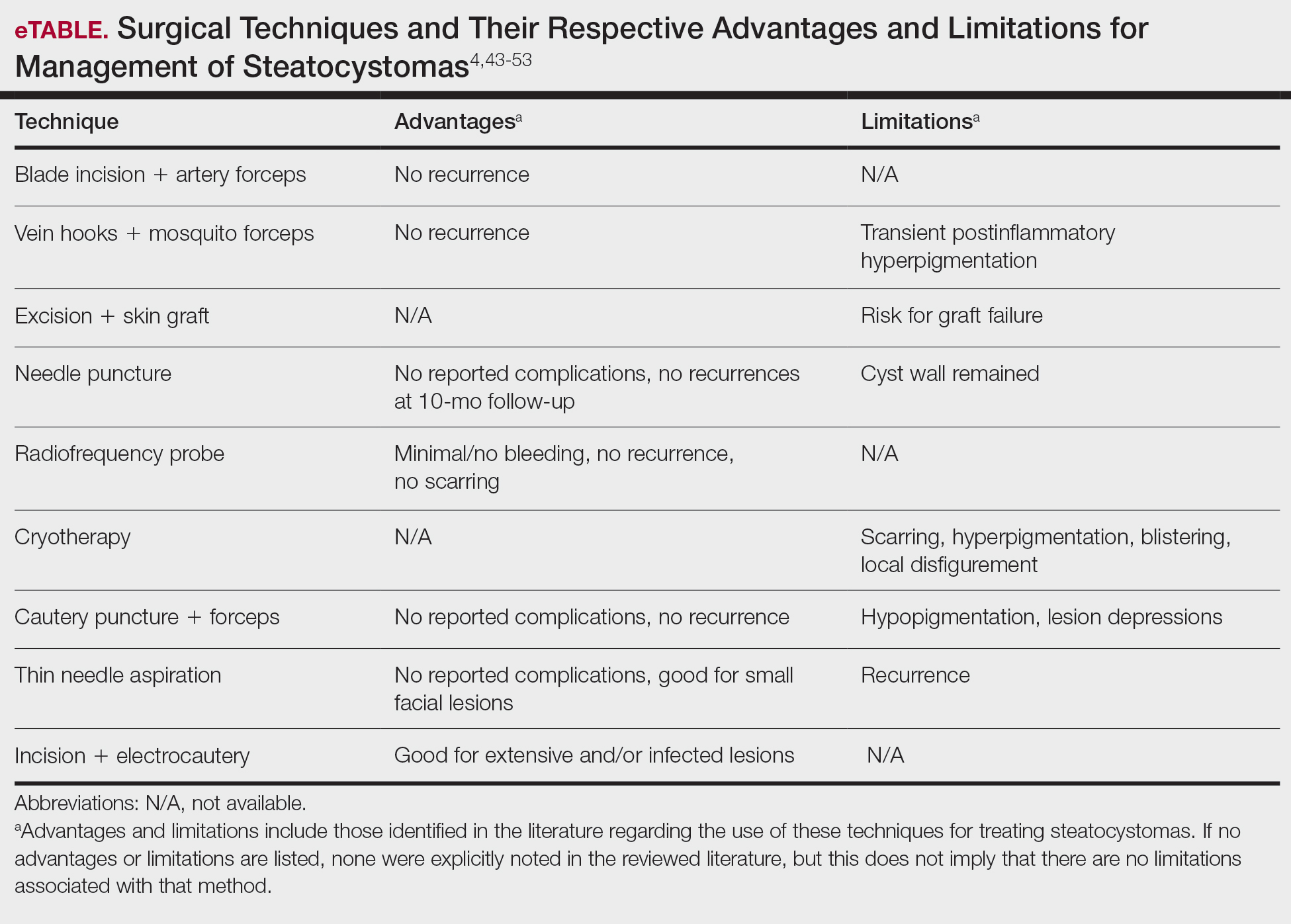

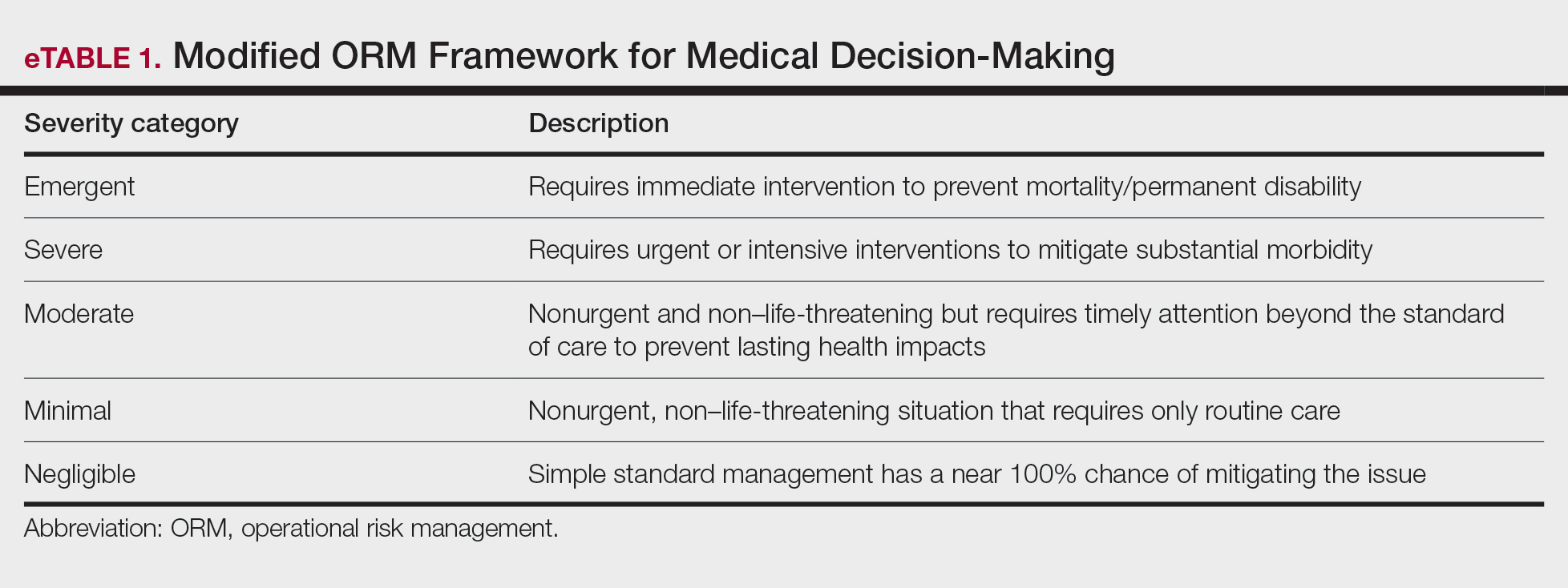

Steatocystomas: Update on Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management

Steatocystomas: Update on Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management

Steatocystomas are small sebum-filled cysts that typically manifest in the dermis and originate from sebaceous follicles. Although commonly asymptomatic, these lesions can manifest with pruritus or become infected, predisposing patients to further complications.1 Steatocystomas can manifest as single (steatocystoma simplex [SS]) or numerous (steatocystoma multiplex [SM]) lesions; the lesions also can spontaneously rupture with characteristics that resemble hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa [SMS]).1,2

Steatocystomas are relatively rare, and there is limited consensus in the published literature on the etiology and management of this condition. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of steatocystomas in the current literature. We highlight important features to consider when making the diagnosis and also offer recommendations for best-practice treatment.

Historical Background

Although not explicitly identified by name, the first documentation of steatocystomas is a case report published in 1873. In this account, the author described a patient who presented with approximately 250 flesh-colored dermal cysts across the body that varied in size.3 In 1899, the term steatocystoma multiple—derived from Greek roots meaning “fatty bag”—was first used.4

In 1982, almost a century later, Brownstein5 reported some of the earliest cases of SS. This solitary subtype is identical to SM on a microscopic level; however, unlike SM, this variant occurs as a single lesion that typically forms in adulthood and in the absence of family history. Other benign adnexal tumors (eg, pilomatricomas, pilar cysts, and sebaceous hyperplasias) also can manifest as either solitary or multiple lesions.

In 1976, McDonald and Reed6 reported the first known cases of patients with both SM and HS. At the time, the co-occurrence of these conditions was viewed as coincidental, but there were postulations of a shared inflammatory process and hereditary link6; it was not until 1982 that the term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum was coined to describe this variant.7 Although rare, there have been multiple documented instances of SMS since. It has been suggested that the convergence of these conditions may indicate a shared follicular proliferation defect.8 Ongoing investigation is warranted to explain the underlying pathogenesis of this unique variant.

Epidemiology

The available epidemiologic data primarily relate to SM, the most common steatocystoma variant. Nevertheless, SM is a relatively rare condition, and the exact incidence and prevalence remain unknown.8,9 Steatocystomas typically manifest in the first and second decades of life and have been observed in patients of both sexes, with studies demonstrating no notable sex bias.4,9

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Steatocystomas can occur sporadically or may be inherited as an autosomal-dominant condition.4 Typically, SS tends to manifest as an isolated occurrence without any inherent genetic predisposition.5 Alternatively, SM may develop sporadically or be associated with a mutation in the keratin 17 gene (KRT17).4 Steatocystoma multiplex also has been associated with at least 4 different missense mutations, including N92H, R94H, and R94C, located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17.4,10-12

The keratin 17 gene is responsible for encoding the keratin 17 protein, a type I intermediate filament predominantly synthesized in the basal cells of epithelial tissue. This fibrous structural protein can regulate many processes, including inflammation and cell proliferation, and is found in regions such as the sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and eccrine sweat glands. Overexpression of KRT17 has been suggested in other cutaneous conditions, most notably psoriasis.12 Despite KRT17’s many roles, it remains unclear why SM typically manifests with a myriad of sebum-containing cysts as the primary symptom.12 Continued investigation into the genetic underpinnings of SM and the keratin 17 protein is necessary to further elucidate a more comprehensive understanding of this condition.

Hormonal influences have been suggested as a potential trigger for steatocystoma growth.4,13 This condition is associated with dysfunction of the sebaceous glands, and, correspondingly, the incidence of disease is highest in pubertal patients, in whom androgen levels and sebum production are elevated.4,13,14 Two cases of transgender men taking testosterone therapy presenting with steatocystomas provide additional clinical support for this association.15

Additionally, the use of immunomodulatory agents, such as ustekinumab (anti–interleukin 12/interleukin 23), has been shown to trigger SM. It is predicted that the reduced expression of certain interferons and interleukins may lead to downstream consequences in the keratin 17 pathway and lead to SM lesion formation in genetically susceptible individuals.16 Targeting these potential causes in the future may prove efficacious in the secondary prevention of familial SM manifestation or exacerbations.

Mutations in the KRT17 gene also have been implicated in pachyonychia congenita type 2 (PC-2).4 Marked by extensive systemic hyperkeratosis, PC-2 has been observed to coincide with SM in certain patients.4,5 Interestingly, the location of the KRT17 mutations are identical in both PC-2 and SM.4 Although most individuals with hereditary SM do not exhibit the characteristic features of PC-2, mild nail and dental abnormalities have been observed in some SM cases.4,10 This relationship suggests that SM may be a less severe variant of PC-2 or part of a complex polygenetic spectrum of disease.10 Further research is imperative to determine the exact nature and extent of the relationship between these conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

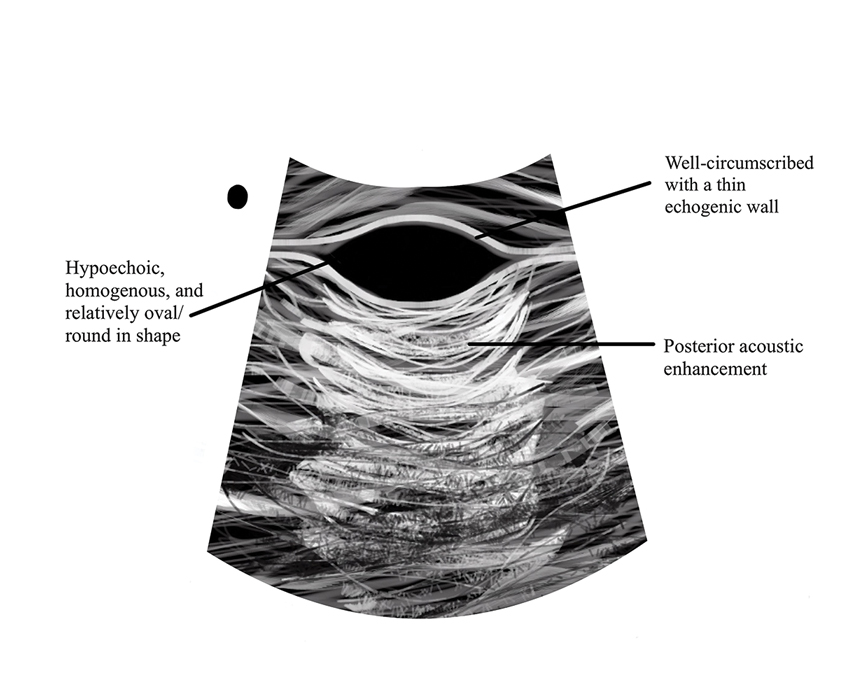

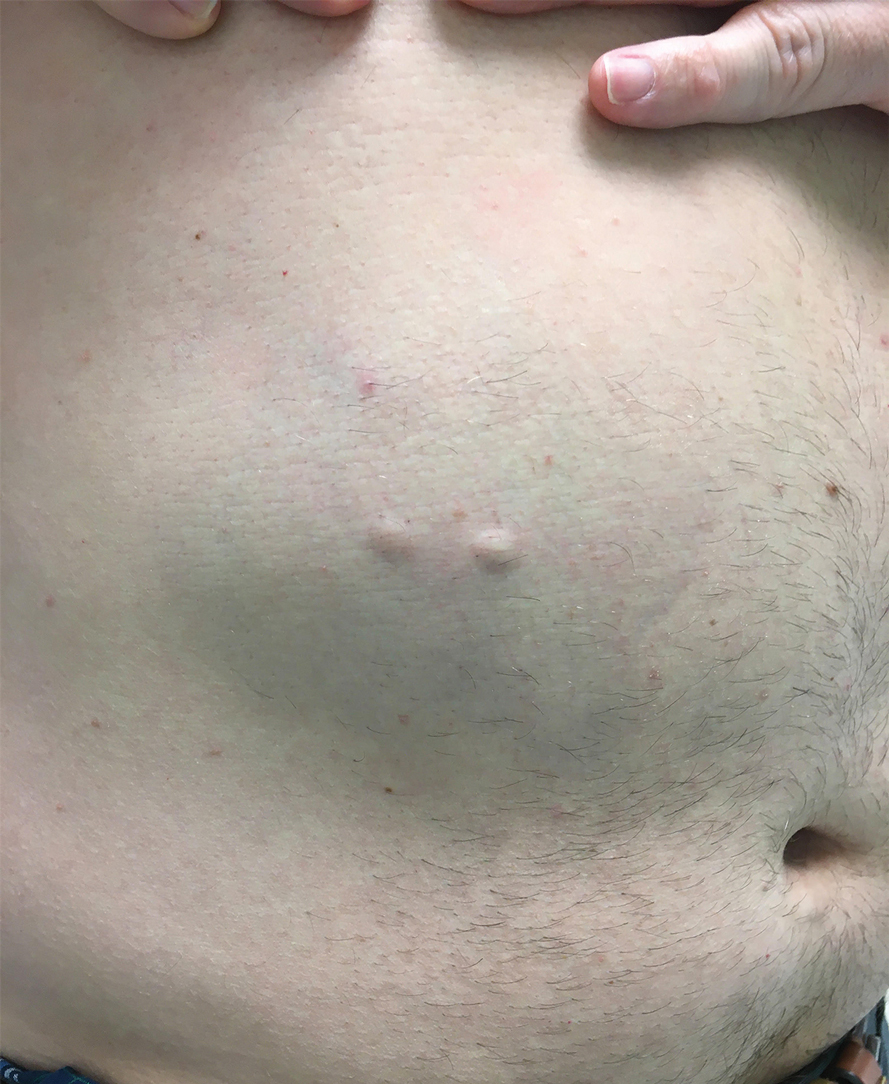

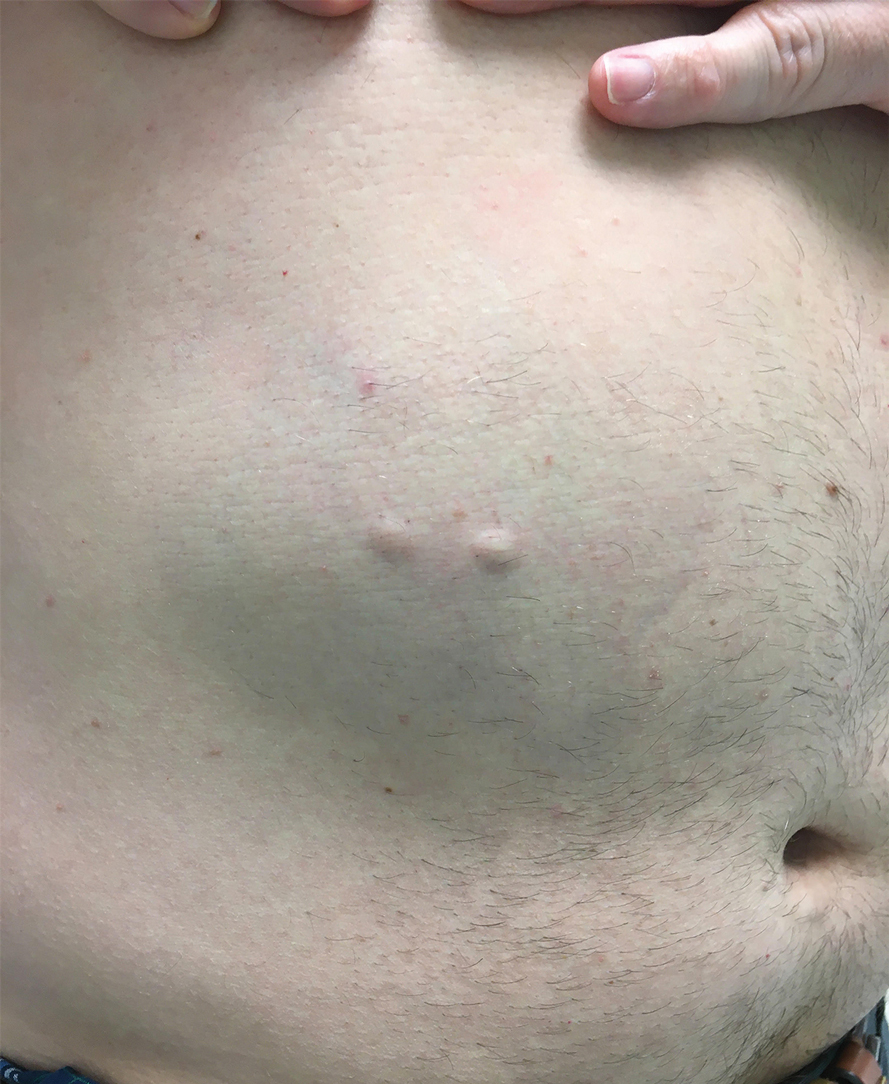

Steatocystomas are flesh-colored subcutaneous cysts that range in size from less than 3 mm to larger than 3 cm in diameter (Figure). They form within a single pilosebaceous unit and typically display firm attachment due to their origination in the dermis.2,7,17 Steatocystomas generally contain lipid material, and less frequently, keratin and hair shafts, distinguishing them as the only “true” sebaceous cysts.18 Their color can range from flesh-toned to yellow, with reports of occasional dark-blue shades and calcifications.19,20 Steatocystomas can persist indefinitely, and they usually are asymptomatic.

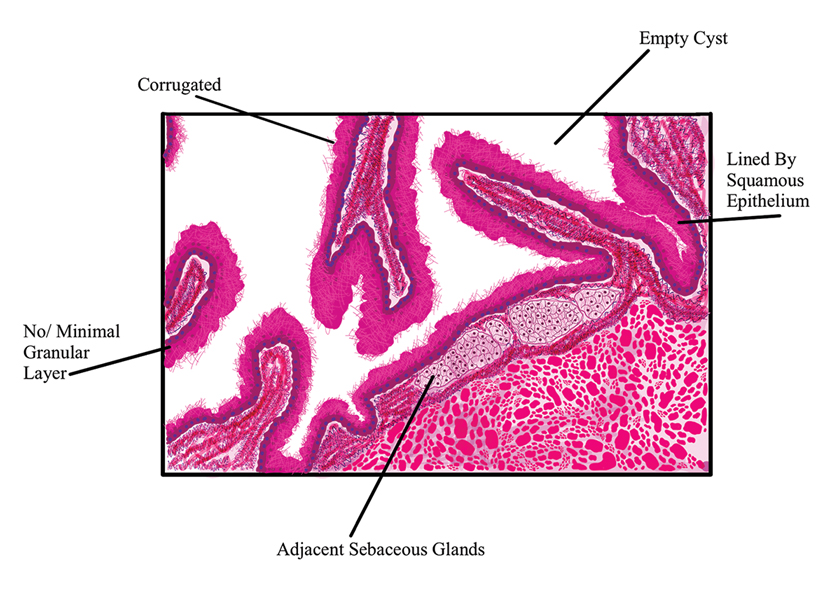

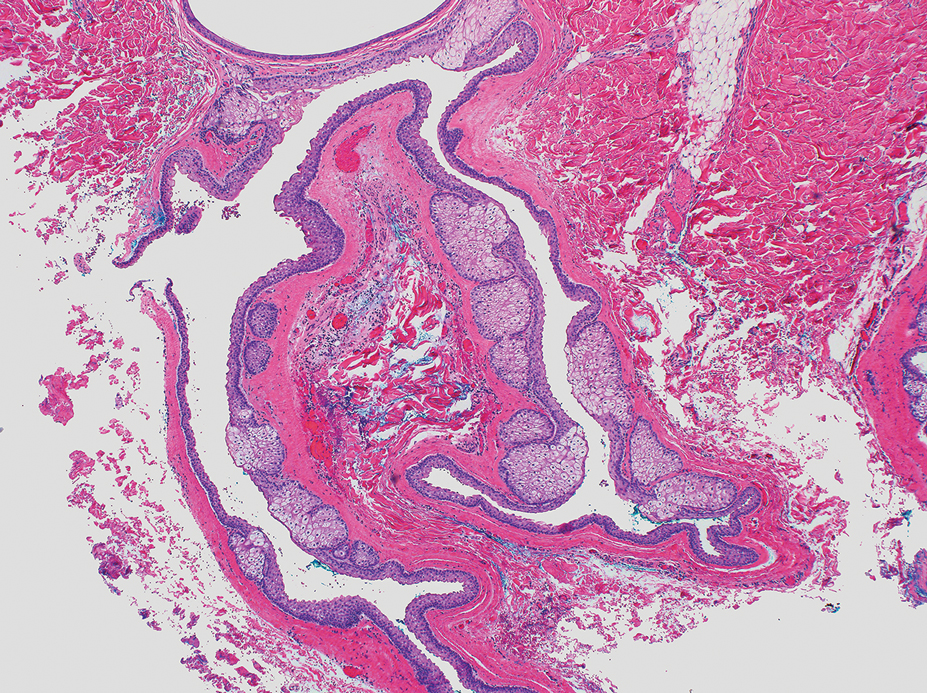

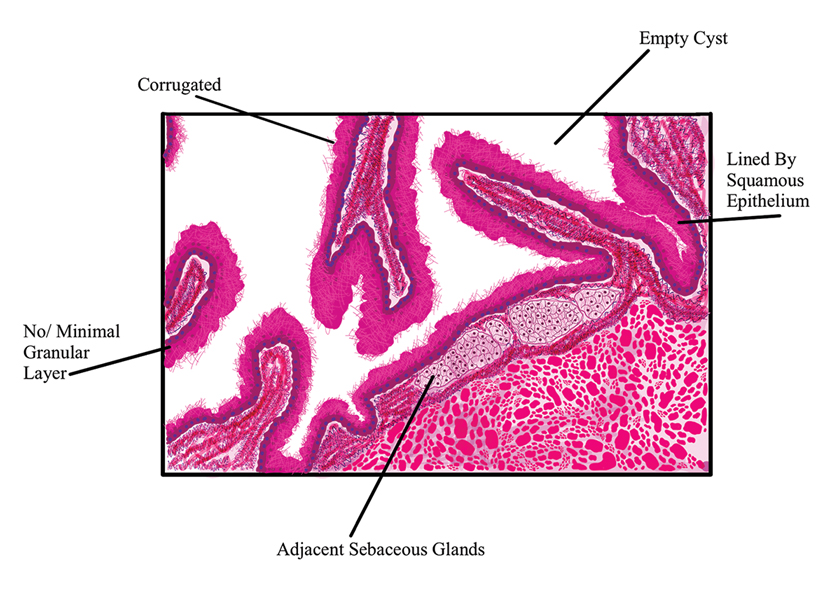

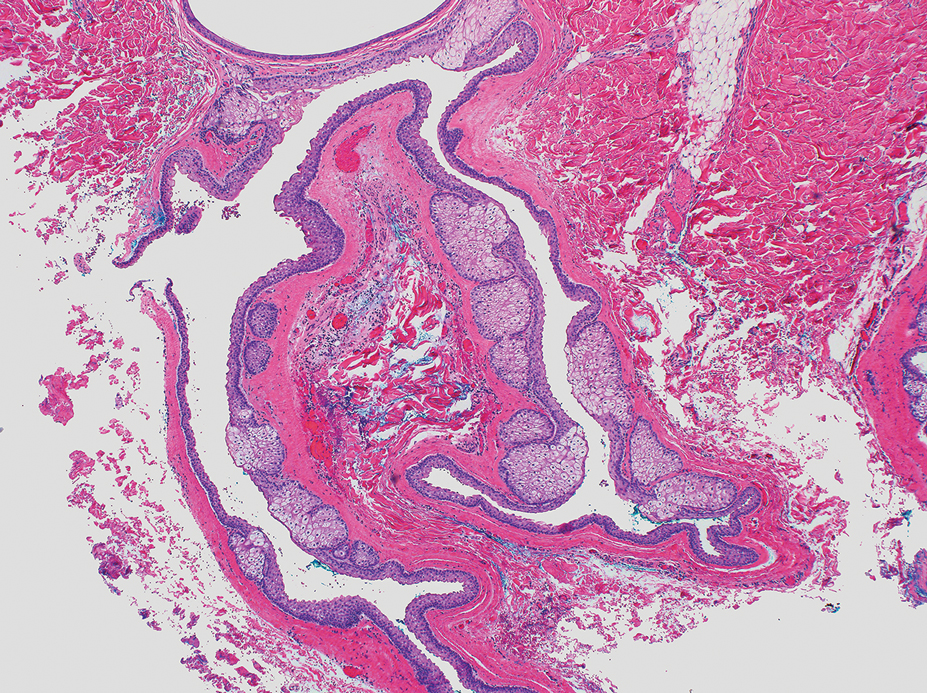

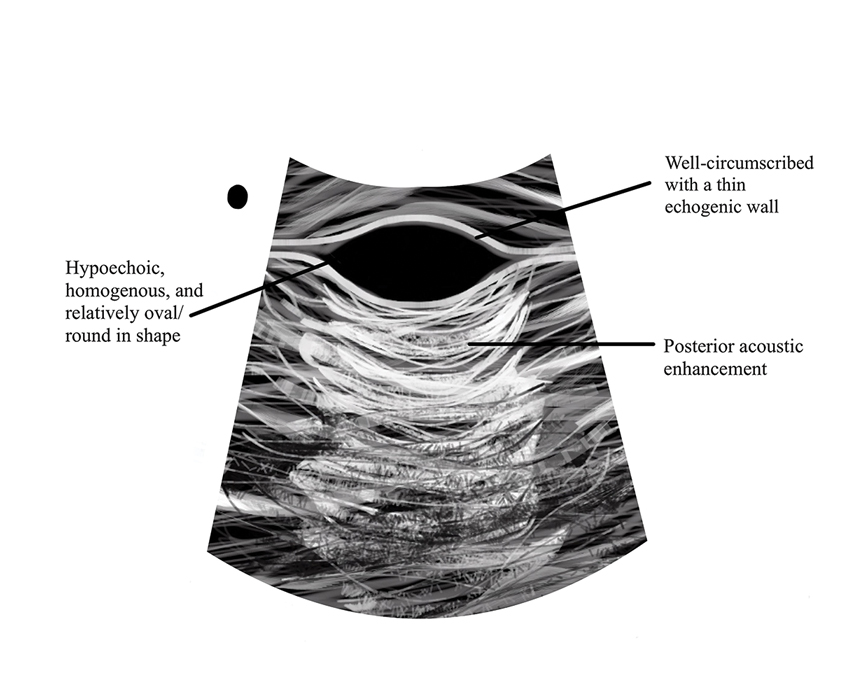

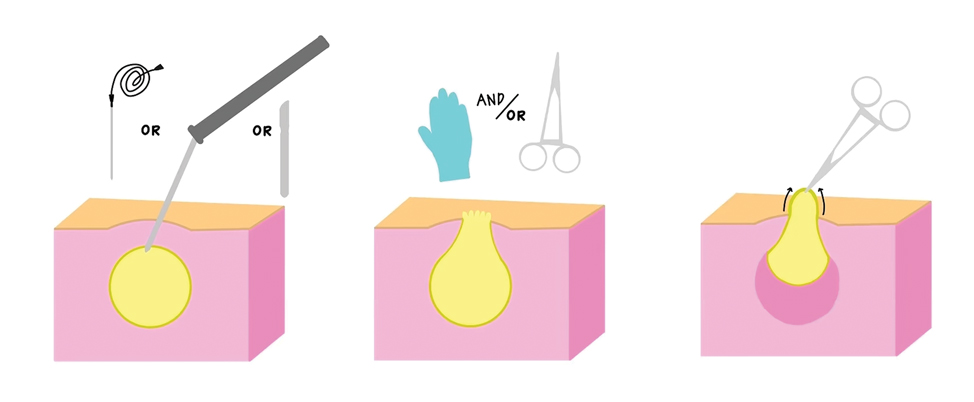

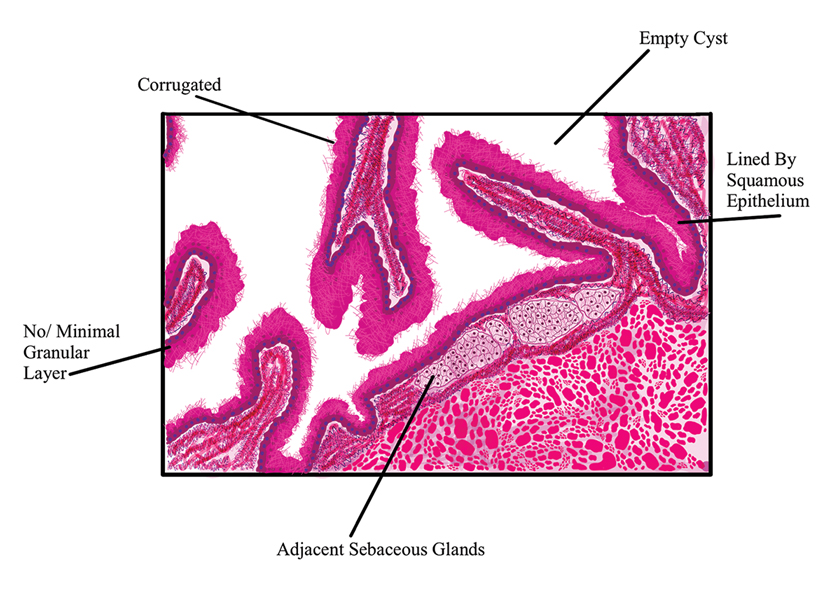

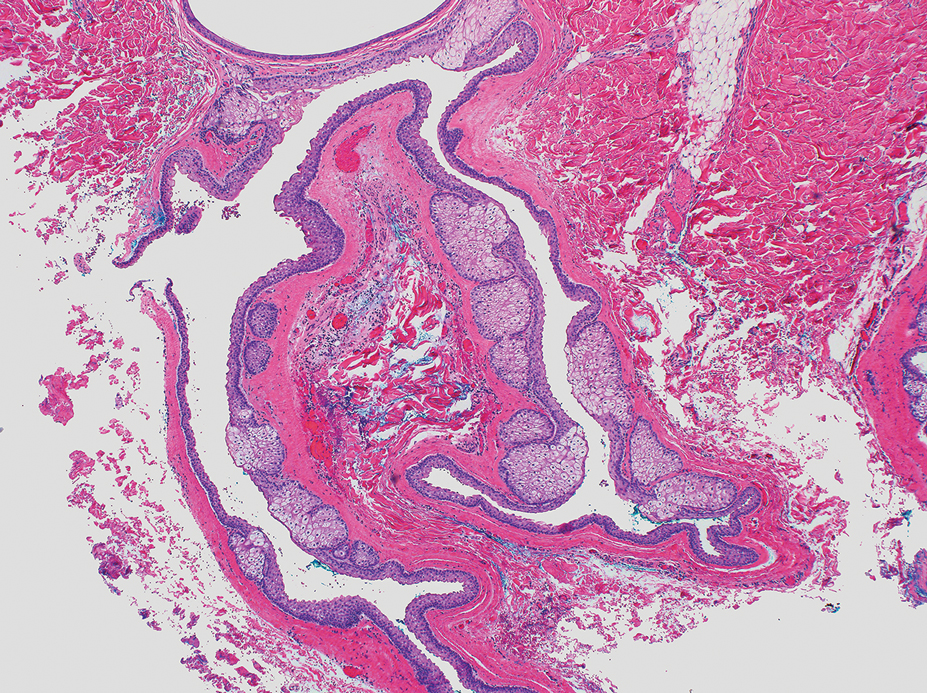

Diagnosis of steatocystoma is confirmed by biopsy.4 Steatocystomas are characterized by a dermal cyst lined by stratified squamous cell epithelium (eFigures 1 and 2).21 Classically they feature flattened sebaceous lobules, multinucleated giant cells, and abortive hair follicles. The lining of these cysts is marked by lymphocytic infiltrate and a dense, wrinkled, eosinophilic keratin cuticle that replaces the granular layer.22 The cyst maintains an epidermal connection through a follicular infundibulum characterized by clumps of keratinocytes, sebocytes, corneocytes, and/or hair follicles.7 Aspirated contents reveal crystalline structures and anucleate squamous cells upon microscopic analysis. That being said, variable histologic findings of steatocystomas have been described.23

Steatocystoma simplex, as the name implies, classifies a single isolated steatocystoma. This subtype exhibits similar histopathologic and clinical features to the other subtypes of steatocystomas. Notably, SS is not associated with a genetic mutation and is not an inherited condition within families.5 Steatocystoma multiplex manifests with many steatocystomas, often distributed widely across the body.3,4 The chest, axillae, and groin are the most common locations; however, these cysts can manifest on the face, back, abdomen, and extremities.4,18-22 Rare occurrences of SM limited to the face, scalp, and distal extremities have been documented.18,21,24,25 Due to the possibility of an autosomal-dominant inheritance, it is advisable to take a comprehensive family history in patients for whom SM is in the differential.17

Steatocystoma multiplex—especially familial variants—has been shown to develop in conjunction with other dermatologic conditions, including eruptive vellus hair (EVH) cysts, persistent infantile milia, and epidermoid/dermoid cysts.26 While some investigators regard these as separate entities due to their varied genetic etiology, it has been suggested that these conditions may be related and that the diagnosis is determined by the location of cyst origin along the sebaceous ducts.26,27 Other dermatologic conditions and lesions that frequently manifest comorbidly with SM include hidrocystomas, syringomas, pilonidal cysts, lichen planus, nodulocystic acne, trichotillomania, trichoblastomas, trichoepithelioma, HS, keratoacanthomas, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and embryonal hair formation. Steatocystoma multiplex, manifesting comorbidly with dental and orofacial malformations (eg, partial noneruption of secondary teeth, natal and defective teeth, and bilateral preauricular sinuses) has been classified as SM natal teeth syndrome.6

Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is a rare and serious variant of SM characterized by inflammation, cyst rupture, sinus tract formation, and scarring.24 Patients with SMS typically have multiple intact SM cysts, which can aid in differentiation from HS.2,24 Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is associated with more complications than SS and SM, including cyst perforation, development of purulent and/or foul-smelling discharge, infection, scarring, pain, and overall discomfort.2