User login

For MD-IQ use only

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

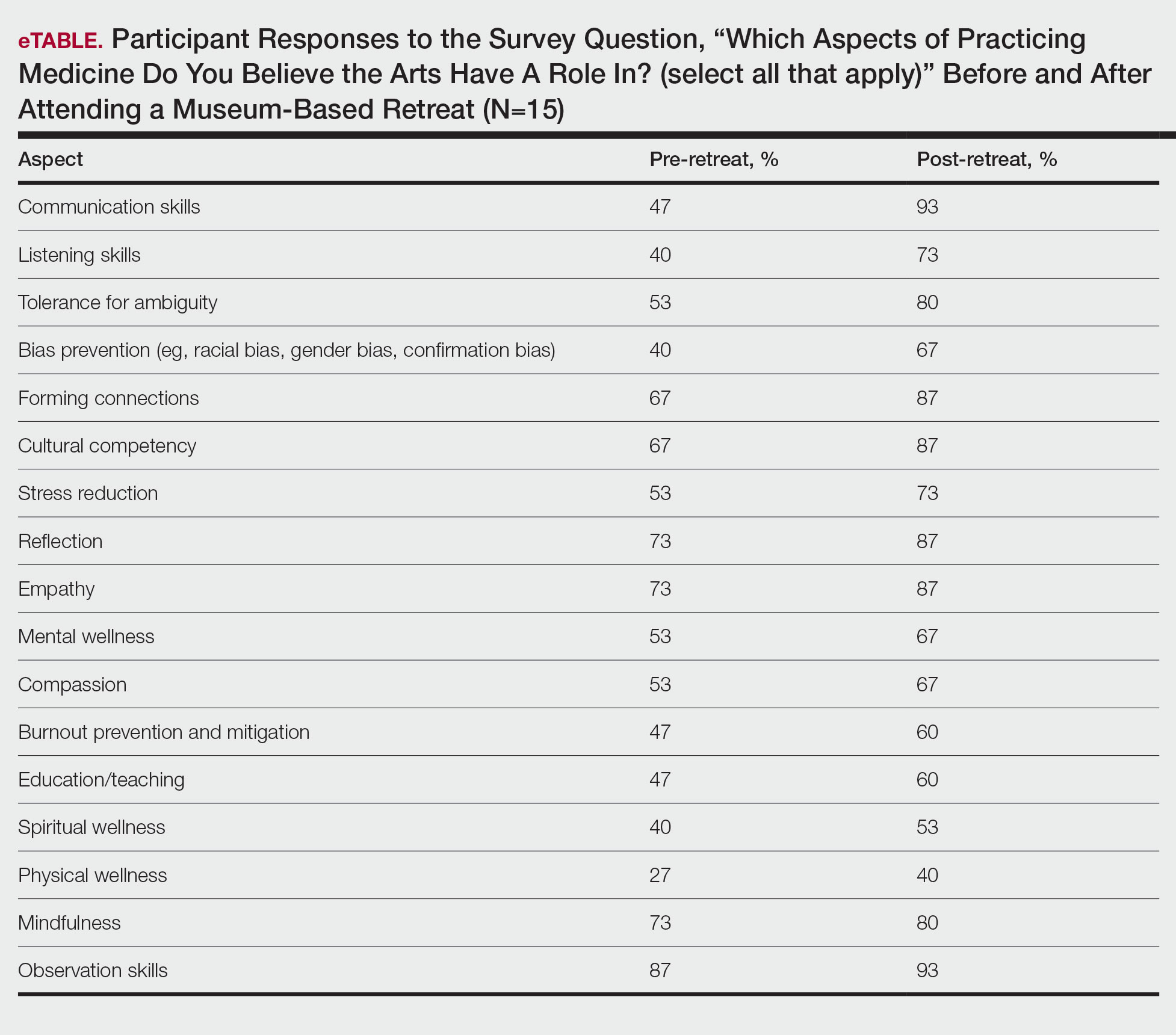

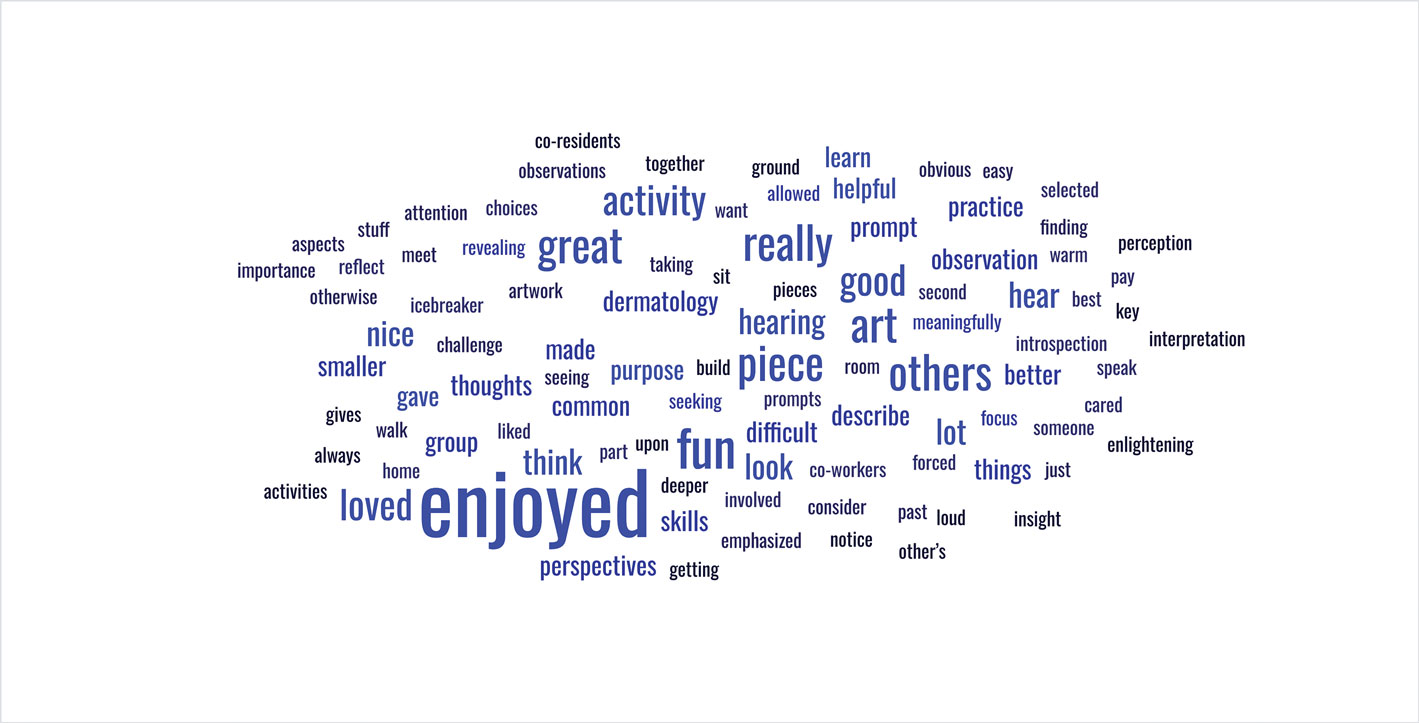

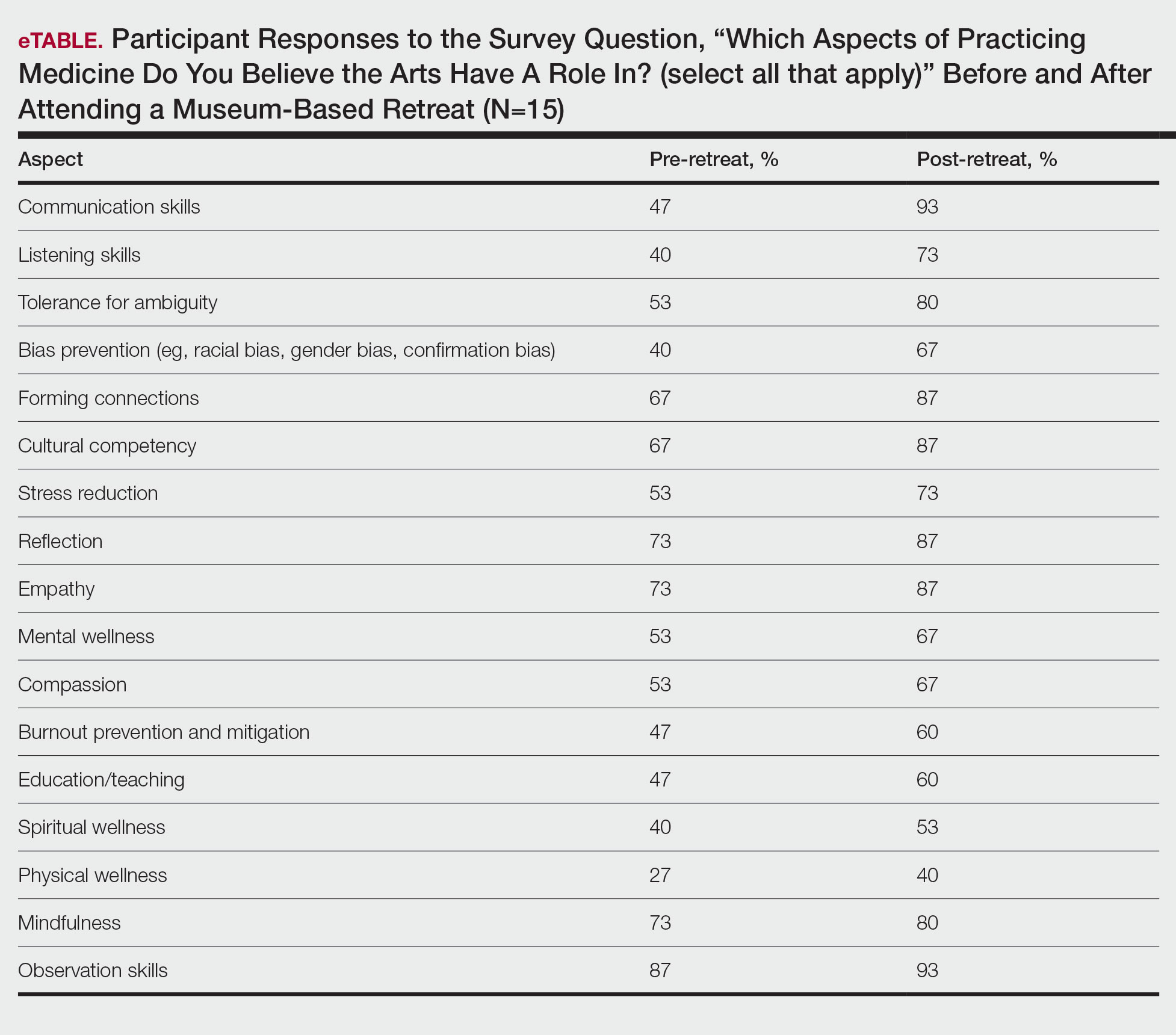

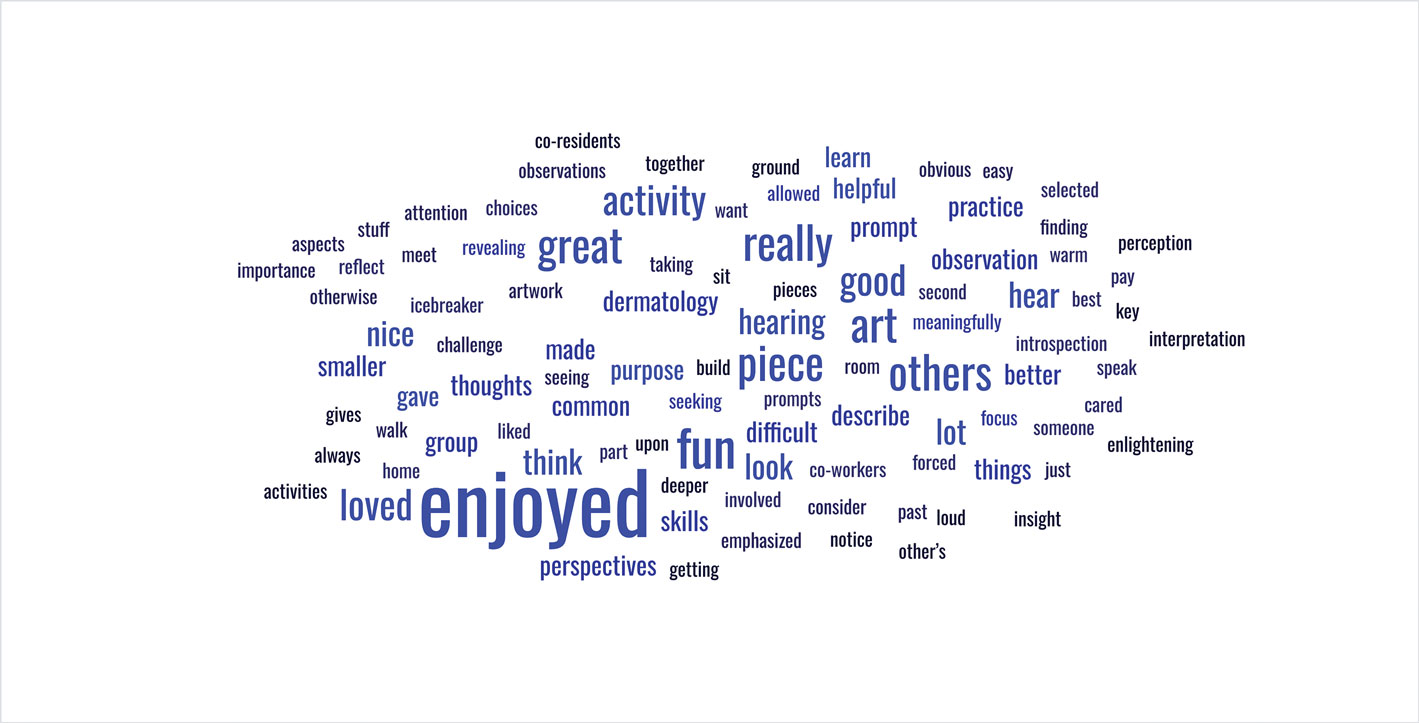

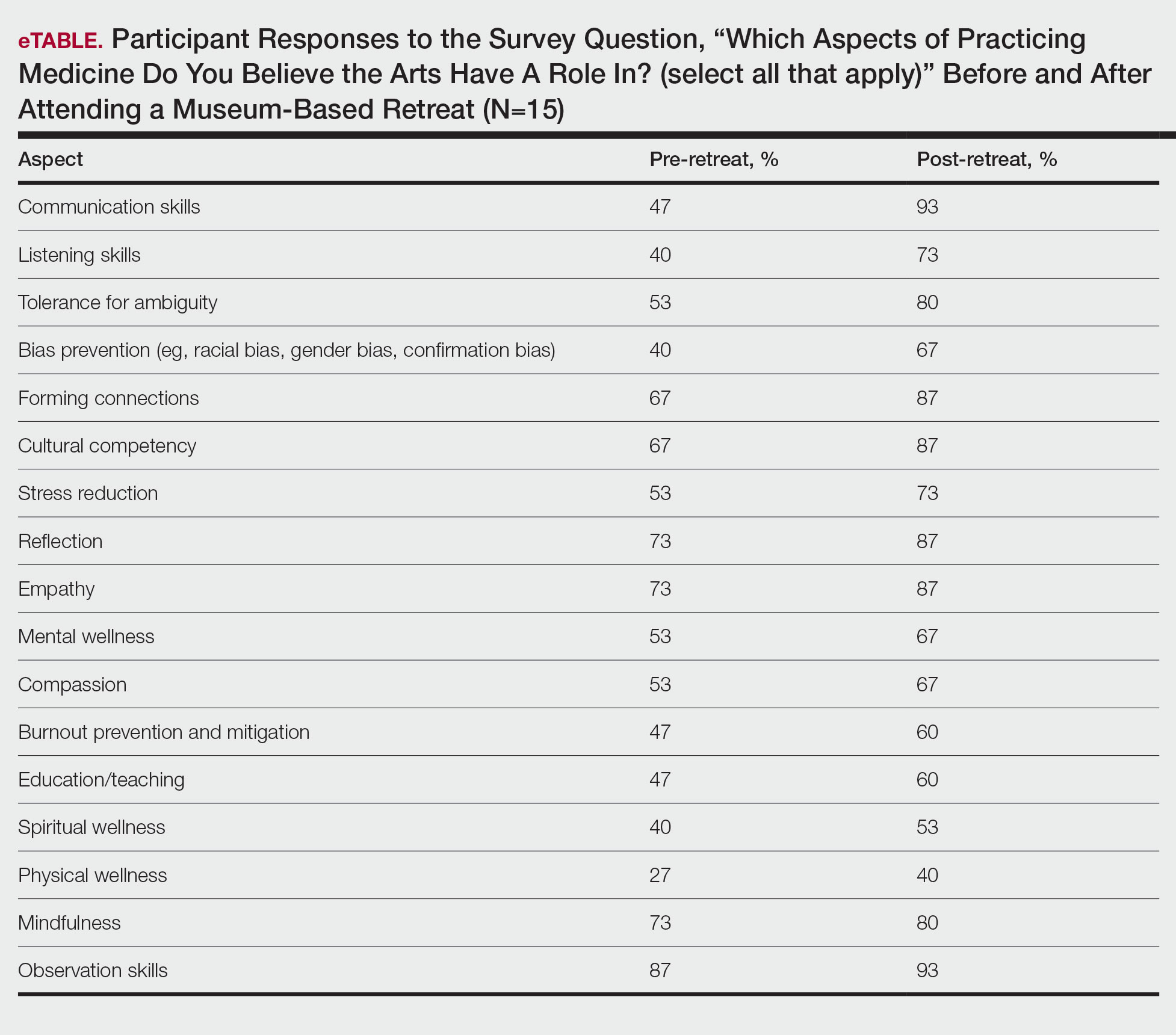

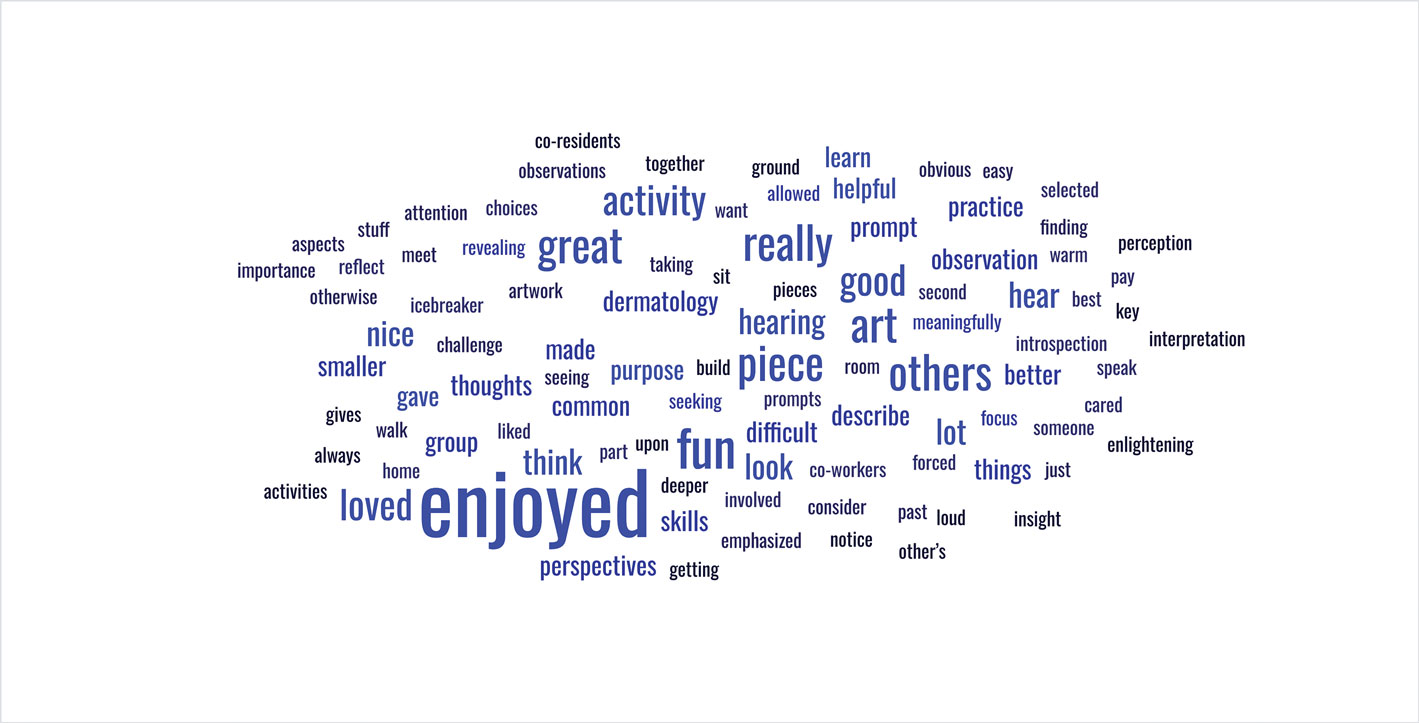

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Practice Points

- Arts-based programming positively impacts resident competencies that are important to the practice of medicine.

- Incorporating arts-based programming in the dermatology residency curriculum can enhance resident well-being and the ability to be better clinicians.

Dark-Brown Macule on the Periumbilical Skin

Dark-Brown Macule on the Periumbilical Skin

THE DIAGNOSIS: Seborrheic Keratosis

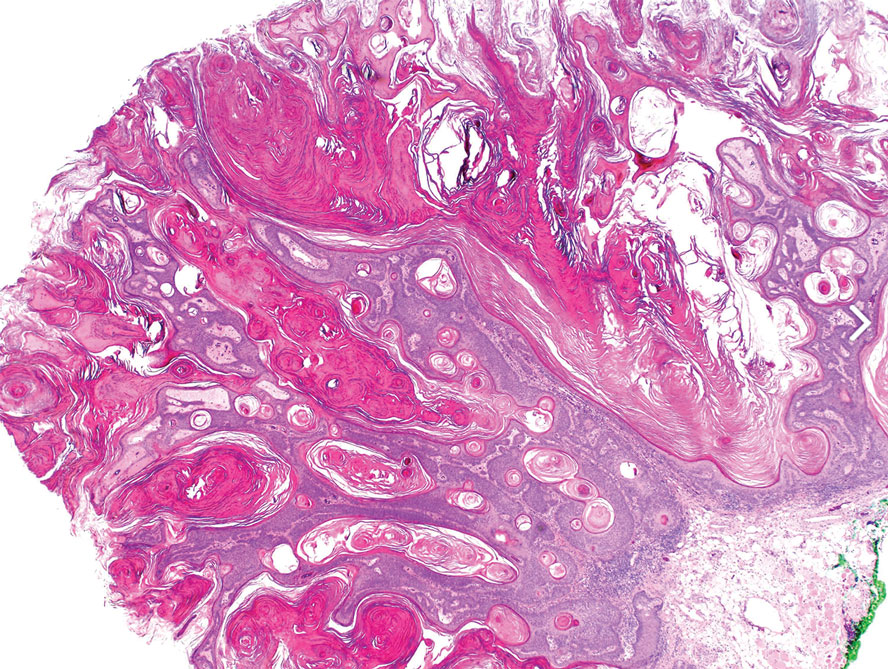

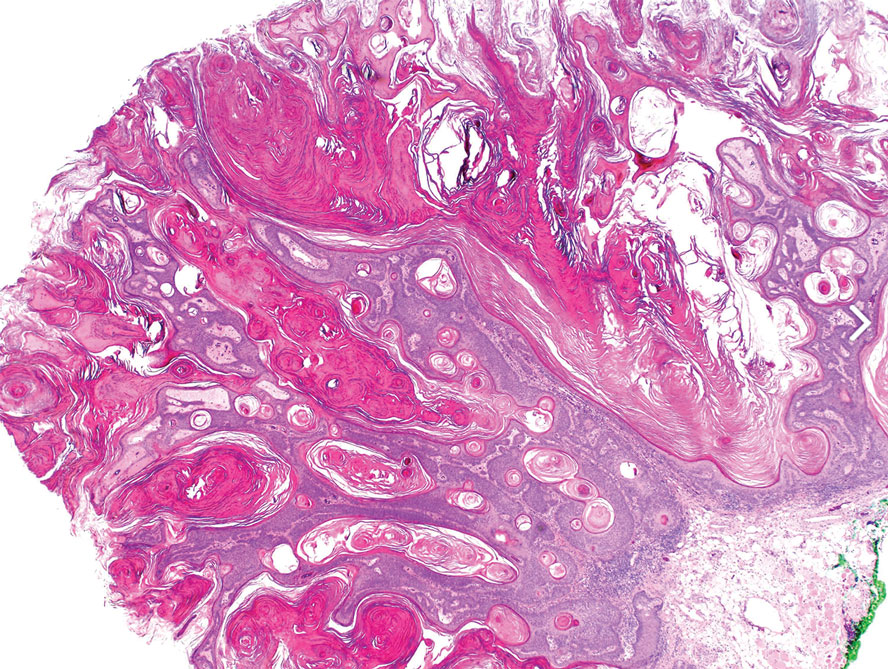

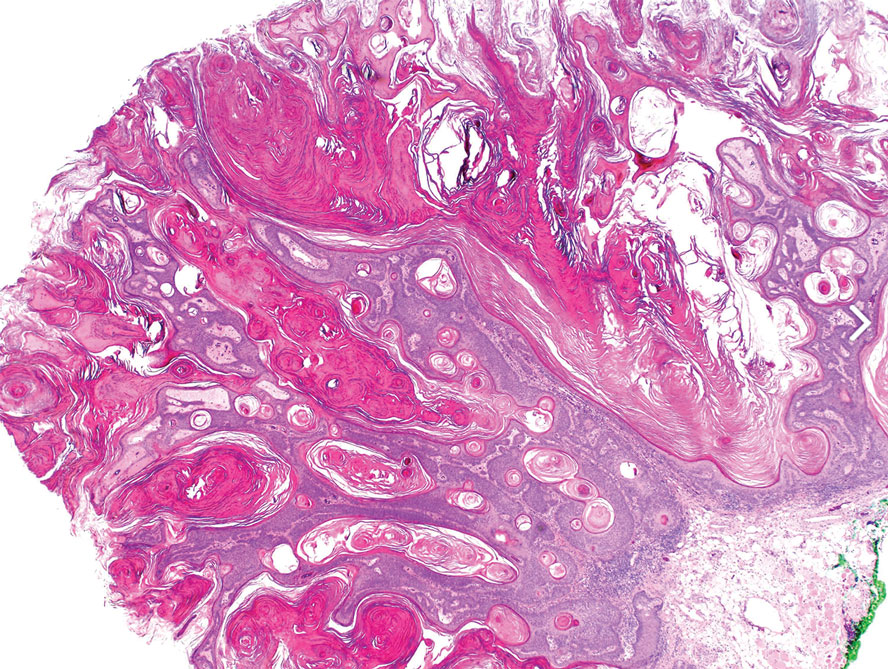

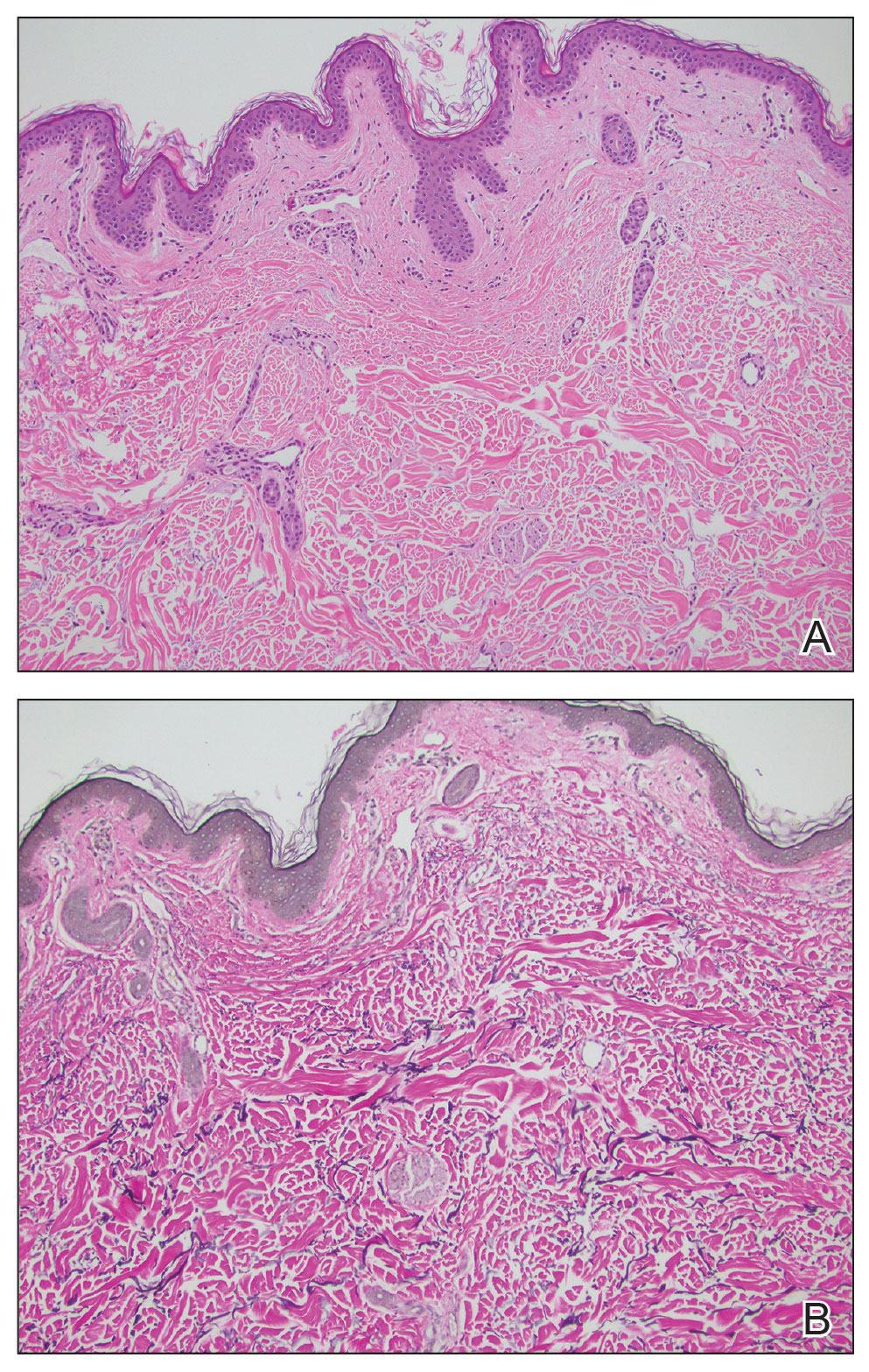

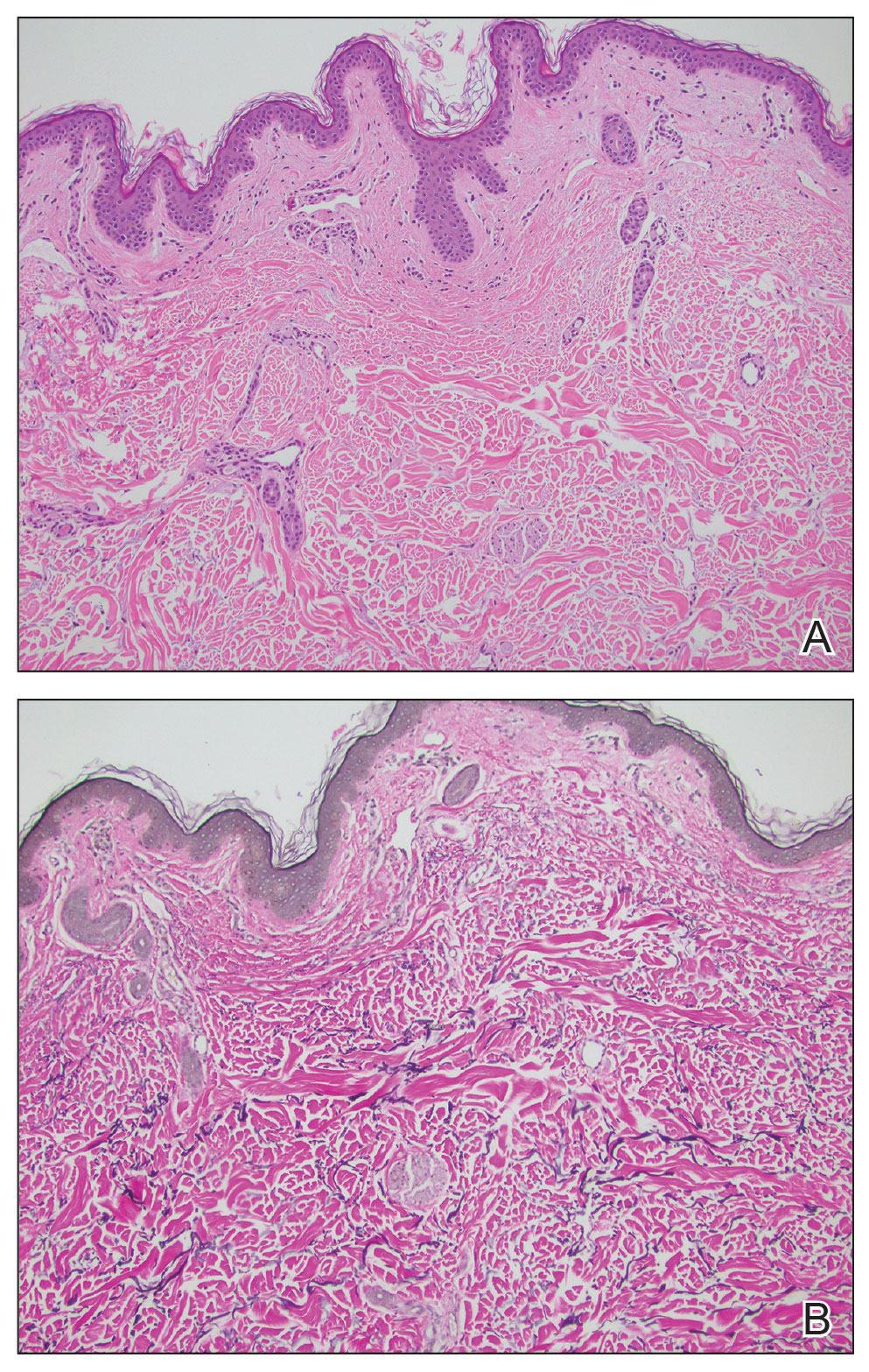

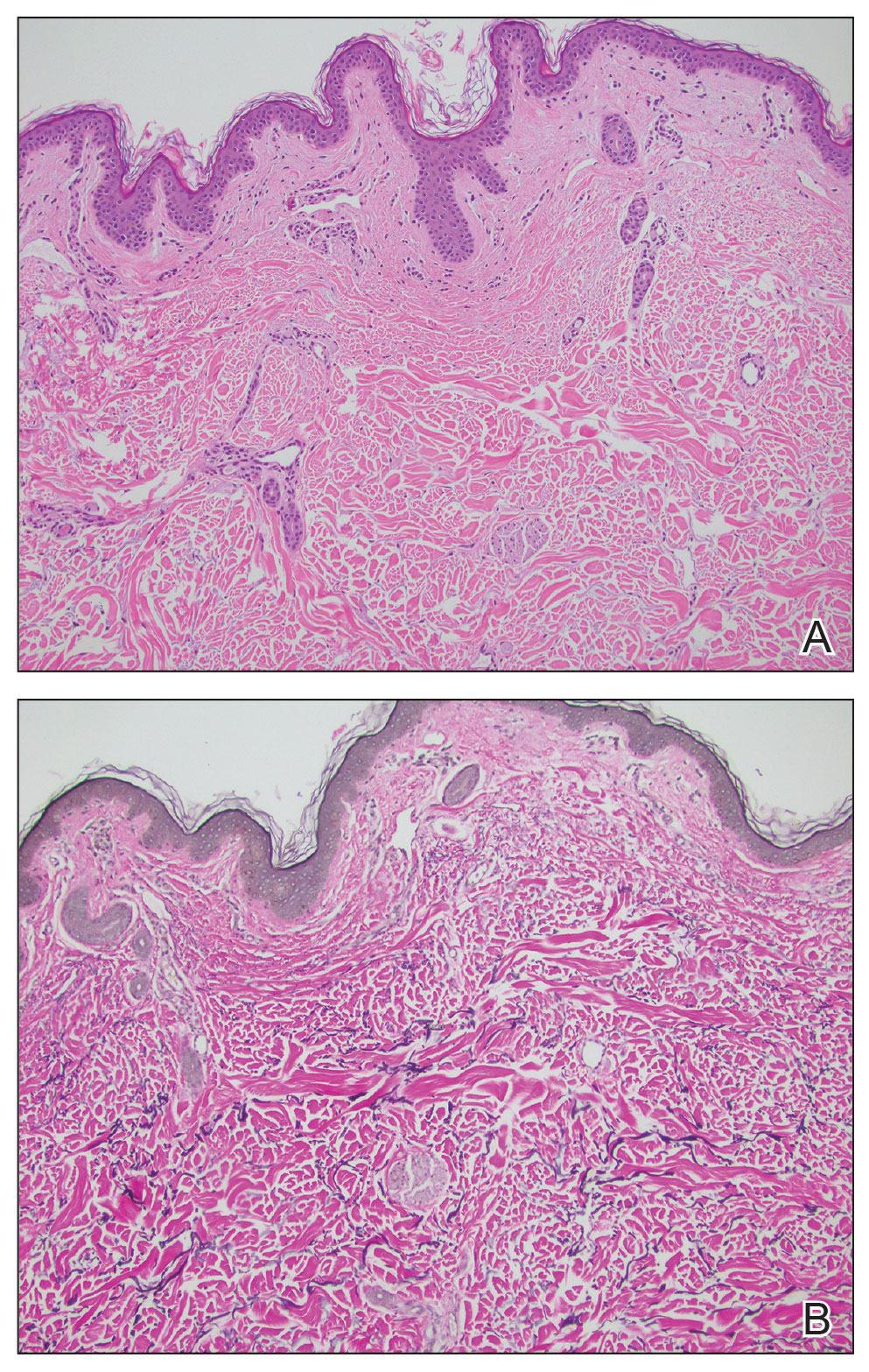

Histopathology revealed epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis with no notation of atypical melanocytic activity (Figure). There were no Kamino bodies, junctional nesting, or cytologic atypia. Based on these features as well as the clinical and dermoscopic findings, a diagnosis of an inflamed seborrheic keratosis (SK) was made. No further treatment was required following the shave biopsy, and the patient was reassured regarding the benign nature of the lesion.

Seborrheic keratoses are benign epidermal growths that can manifest on any area of the skin except the palms and soles. They present clinically as tan, yellow, gray, brown, or black with a smooth, waxy, or verrucous surface. They range from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter. Although SKs traditionally manifest more frequently in individuals with lighter skin tones, pigmented variants, such as dermatosis papulosa nigra, have been reported to occur more commonly and at younger ages in patients with skin of color.1

Dermoscopy of SK in patients with skin of color can present diagnostic challenges, as these lesions may display atypical pigmented patterns that overlap with melanocytic lesions, including Spitz nevi, particularly when starburstlike or globular structures are present.2 What sets inflamed SKs apart from other SKs is the lack of a heavily keratinized surface on both clinical and dermoscopic evaluation. Common histopathologic diagnostic criteria for Spitz nevi include Kamino bodies, uniform nuclear enlargement, and spindled or epithelioid nevus cells, which were not noted in our patient.3 Therefore, in presentations such as this, histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis in this case included benign nevus, dysplastic nevus, melanoma, and Spitz nevus. Benign nevi typically demonstrate uniform pigmentation and symmetric dermoscopic patterns. Dysplastic nevi may show architectural disorder and cytologic atypia but lack invasive features.3 Melanoma often exhibits asymmetry, atypical network patterns, and irregular pigmentation.4 Spitz nevi characteristically demonstrate large epithelioid or spindle cells with Kamino bodies on histopathology, which were absent in our patient.

- Greco MJ, Bhutta BS. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated May 6, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/

- Emanuel P, Cheng, H. Spitz naevus pathology. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/spitz-naevus-pathology.

- Wensley KE, Zito PM. Atypical mole. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560606/

- Valenzuela FI, Hohnadel M. Dermatoscopic characteristics of melanoma versus benign lesions and nonmelanoma cancers. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 10, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK606113/

THE DIAGNOSIS: Seborrheic Keratosis

Histopathology revealed epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis with no notation of atypical melanocytic activity (Figure). There were no Kamino bodies, junctional nesting, or cytologic atypia. Based on these features as well as the clinical and dermoscopic findings, a diagnosis of an inflamed seborrheic keratosis (SK) was made. No further treatment was required following the shave biopsy, and the patient was reassured regarding the benign nature of the lesion.

Seborrheic keratoses are benign epidermal growths that can manifest on any area of the skin except the palms and soles. They present clinically as tan, yellow, gray, brown, or black with a smooth, waxy, or verrucous surface. They range from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter. Although SKs traditionally manifest more frequently in individuals with lighter skin tones, pigmented variants, such as dermatosis papulosa nigra, have been reported to occur more commonly and at younger ages in patients with skin of color.1

Dermoscopy of SK in patients with skin of color can present diagnostic challenges, as these lesions may display atypical pigmented patterns that overlap with melanocytic lesions, including Spitz nevi, particularly when starburstlike or globular structures are present.2 What sets inflamed SKs apart from other SKs is the lack of a heavily keratinized surface on both clinical and dermoscopic evaluation. Common histopathologic diagnostic criteria for Spitz nevi include Kamino bodies, uniform nuclear enlargement, and spindled or epithelioid nevus cells, which were not noted in our patient.3 Therefore, in presentations such as this, histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis in this case included benign nevus, dysplastic nevus, melanoma, and Spitz nevus. Benign nevi typically demonstrate uniform pigmentation and symmetric dermoscopic patterns. Dysplastic nevi may show architectural disorder and cytologic atypia but lack invasive features.3 Melanoma often exhibits asymmetry, atypical network patterns, and irregular pigmentation.4 Spitz nevi characteristically demonstrate large epithelioid or spindle cells with Kamino bodies on histopathology, which were absent in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Seborrheic Keratosis

Histopathology revealed epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis with no notation of atypical melanocytic activity (Figure). There were no Kamino bodies, junctional nesting, or cytologic atypia. Based on these features as well as the clinical and dermoscopic findings, a diagnosis of an inflamed seborrheic keratosis (SK) was made. No further treatment was required following the shave biopsy, and the patient was reassured regarding the benign nature of the lesion.

Seborrheic keratoses are benign epidermal growths that can manifest on any area of the skin except the palms and soles. They present clinically as tan, yellow, gray, brown, or black with a smooth, waxy, or verrucous surface. They range from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter. Although SKs traditionally manifest more frequently in individuals with lighter skin tones, pigmented variants, such as dermatosis papulosa nigra, have been reported to occur more commonly and at younger ages in patients with skin of color.1

Dermoscopy of SK in patients with skin of color can present diagnostic challenges, as these lesions may display atypical pigmented patterns that overlap with melanocytic lesions, including Spitz nevi, particularly when starburstlike or globular structures are present.2 What sets inflamed SKs apart from other SKs is the lack of a heavily keratinized surface on both clinical and dermoscopic evaluation. Common histopathologic diagnostic criteria for Spitz nevi include Kamino bodies, uniform nuclear enlargement, and spindled or epithelioid nevus cells, which were not noted in our patient.3 Therefore, in presentations such as this, histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis in this case included benign nevus, dysplastic nevus, melanoma, and Spitz nevus. Benign nevi typically demonstrate uniform pigmentation and symmetric dermoscopic patterns. Dysplastic nevi may show architectural disorder and cytologic atypia but lack invasive features.3 Melanoma often exhibits asymmetry, atypical network patterns, and irregular pigmentation.4 Spitz nevi characteristically demonstrate large epithelioid or spindle cells with Kamino bodies on histopathology, which were absent in our patient.

- Greco MJ, Bhutta BS. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated May 6, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/

- Emanuel P, Cheng, H. Spitz naevus pathology. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/spitz-naevus-pathology.

- Wensley KE, Zito PM. Atypical mole. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560606/

- Valenzuela FI, Hohnadel M. Dermatoscopic characteristics of melanoma versus benign lesions and nonmelanoma cancers. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 10, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK606113/

- Greco MJ, Bhutta BS. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated May 6, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/

- Emanuel P, Cheng, H. Spitz naevus pathology. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/spitz-naevus-pathology.

- Wensley KE, Zito PM. Atypical mole. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560606/

- Valenzuela FI, Hohnadel M. Dermatoscopic characteristics of melanoma versus benign lesions and nonmelanoma cancers. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 10, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK606113/

Dark-Brown Macule on the Periumbilical Skin

Dark-Brown Macule on the Periumbilical Skin

A 33-year-old man with moderately to deeply pigmented skin presented to the dermatology department with a dark-brown macule in the periumbilical area of more than 1 year’s duration. The patient was otherwise healthy and reported no personal or family history of atypical nevi, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or melanoma. Dermoscopy of the lesion showed a dark brown macule less than 2 mm in diameter with a starburst like pattern and a blue-hued border. A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

The Habit of Curiosity: How Writing Shapes Clinical Thinking in Medical Training

The Habit of Curiosity: How Writing Shapes Clinical Thinking in Medical Training

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.

I have learned that writing forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am seeing every day. It turns routine work into something I must understand well enough to explain. Even a small write-up can make me notice details I would otherwise skim past in clinic or surgery. These days, most of my projects start small: a case that taught me something, an observation that made me pause and think. Those seemingly small questions are what eventually grow into bigger ones. The clinical trial I am designing now did not begin as a grand plan—it started because I could not stop thinking about how we manage pain and analgesia after Mohs surgery. That curiosity, shaped by the experience of writing those earlier “smaller” papers, evolved into a study that might actually help improve patient care one day. Still, most of what I write will not revolutionize the field. It is not cutting-edge science or paradigm-shifting data; it is mostly modest analyses with a few interesting conclusions or surgical pearls that might cut down on a patient’s procedural time or save a dermatologist somewhere a few sutures. But it still feels worth doing.

While rotating with Dr. Anna Bar at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall titled, “Top 10 Reasons Why Our Faculty Are Dedicated to Academics and Teaching,” based on the wisdom of Dr. Jane M. Grant-Kels.2 My favorite line on the poster reads, “Residents make us better by asking questions.” I think this philosophy is the main reason why I still write. Even though I am not a resident anymore, I am still asking questions. But if I had to sum up my “why” into a neat list, here is what it might look like:

Because asking questions keeps your brain wired for curiosity. Even small projects train us to remain curious, and this curiosity can mean the difference between just doing your job and continuing to evolve within it. As Dr. Rodolfo Neirotti reminds us, “Questions are useful tools—they open communication, improve understanding, and drive scientific research. In medicine, doing things without knowing why is risky.”3

Because the small stuff builds the culture. Dermatology is a small world. Even short case series, pearls, or “how we do it” pieces can shape how we practice. They may not change paradigms, but they can refine them. Over time, those small practical contributions become part of the field’s collective muscle memory.

Because it preserves perspective. Residency, fellowship, and early practice can blur together. A tiny project can become a timestamp of what you were learning or caring about at that specific moment. Years later, you may remember the case through the paper.

Because the act of writing is the point. Writing forces clarity. You cannot hide behind saying, “That’s just how I do things,” when you have to explain it to others. The discipline of organizing your thoughts sharpens your clinical reasoning and keeps you honest about what you actually know.

Because sometimes it is simply about participating. Publishing, even small pieces, is a way of staying in touch with your field. It says, “I’m still here. I’m still paying attention.”

I think about how Dr. Frederic Mohs developed the technique that now bears his name while he was still a medical student.4 He could have said, “I already made it into medical school. That’s enough.” But he did not. I guess my point is not that we are all on the verge of inventing something revolutionary; it is that innovation happens only when curiosity keeps moving us forward. So no, I do not write to check boxes anymore. I write because it keeps me curious, and I have realized that curiosity is a habit I never want to outgrow.

Or maybe it’s because Jay keeps me up at night, and I have nothing better to do.

- Jeha GM. A roadmap to research opportunities for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;114:E53-E56.

- Grant-Kels J. The gift that keeps on giving. UConn Health Dermatology. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://health.uconn.edu/dermatology/education/

- Neirotti RA. The importance of asking questions and doing things for a reason. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;36:I-II.

- Trost LB, Bailin PL. History of Mohs surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:135-139, vii.

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.

I have learned that writing forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am seeing every day. It turns routine work into something I must understand well enough to explain. Even a small write-up can make me notice details I would otherwise skim past in clinic or surgery. These days, most of my projects start small: a case that taught me something, an observation that made me pause and think. Those seemingly small questions are what eventually grow into bigger ones. The clinical trial I am designing now did not begin as a grand plan—it started because I could not stop thinking about how we manage pain and analgesia after Mohs surgery. That curiosity, shaped by the experience of writing those earlier “smaller” papers, evolved into a study that might actually help improve patient care one day. Still, most of what I write will not revolutionize the field. It is not cutting-edge science or paradigm-shifting data; it is mostly modest analyses with a few interesting conclusions or surgical pearls that might cut down on a patient’s procedural time or save a dermatologist somewhere a few sutures. But it still feels worth doing.

While rotating with Dr. Anna Bar at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall titled, “Top 10 Reasons Why Our Faculty Are Dedicated to Academics and Teaching,” based on the wisdom of Dr. Jane M. Grant-Kels.2 My favorite line on the poster reads, “Residents make us better by asking questions.” I think this philosophy is the main reason why I still write. Even though I am not a resident anymore, I am still asking questions. But if I had to sum up my “why” into a neat list, here is what it might look like:

Because asking questions keeps your brain wired for curiosity. Even small projects train us to remain curious, and this curiosity can mean the difference between just doing your job and continuing to evolve within it. As Dr. Rodolfo Neirotti reminds us, “Questions are useful tools—they open communication, improve understanding, and drive scientific research. In medicine, doing things without knowing why is risky.”3

Because the small stuff builds the culture. Dermatology is a small world. Even short case series, pearls, or “how we do it” pieces can shape how we practice. They may not change paradigms, but they can refine them. Over time, those small practical contributions become part of the field’s collective muscle memory.

Because it preserves perspective. Residency, fellowship, and early practice can blur together. A tiny project can become a timestamp of what you were learning or caring about at that specific moment. Years later, you may remember the case through the paper.

Because the act of writing is the point. Writing forces clarity. You cannot hide behind saying, “That’s just how I do things,” when you have to explain it to others. The discipline of organizing your thoughts sharpens your clinical reasoning and keeps you honest about what you actually know.

Because sometimes it is simply about participating. Publishing, even small pieces, is a way of staying in touch with your field. It says, “I’m still here. I’m still paying attention.”

I think about how Dr. Frederic Mohs developed the technique that now bears his name while he was still a medical student.4 He could have said, “I already made it into medical school. That’s enough.” But he did not. I guess my point is not that we are all on the verge of inventing something revolutionary; it is that innovation happens only when curiosity keeps moving us forward. So no, I do not write to check boxes anymore. I write because it keeps me curious, and I have realized that curiosity is a habit I never want to outgrow.

Or maybe it’s because Jay keeps me up at night, and I have nothing better to do.

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.