User login

Skin Diseases Associated With COVID-19: A Narrative Review

COVID-19 is a potentially severe systemic disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) caused fatal epidemics in Asia in 2002 to 2003 and in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, respectively. In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in patients with severe, sometimes fatal pneumonia of previously unknown origin; it rapidly spread around the world, and the World Health Organization declared the disease a pandemic on March 11, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus that is genetically related to the bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV; it is a single-stranded RNA virus of which several variants and subvariants exist. The SARS-CoV-2 viral particles bind via their surface spike protein (S protein) to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor present on the membrane of several cell types, including epidermal and adnexal keratinocytes.1,2 The α and δ variants, predominant from 2020 to 2021, mainly affected the lower respiratory tract and caused severe, potentially fatal pneumonia, especially in patients older than 65 years and/or with comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and (iatrogenic) immunosuppression. The ο variant, which appeared in late 2021, is more contagious than the initial variants, but it causes a less severe disease preferentially affecting the upper respiratory airways.3 As of April 5, 2023, more than 762,000,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, causing more than 6,800,000 deaths.4

Early studies from China describing the symptoms of COVID-19 reported a low frequency of skin manifestations (0.2%), probably because they were focused on the most severe disease symptoms.5 Subsequently, when COVID-19 spread to the rest of the world, an increasing number of skin manifestations were reported in association with the disease. After the first publication from northern Italy in spring 2020, which was specifically devoted to skin manifestations of COVID-19,6 an explosive number of publications reported a large number of skin manifestations, and national registries were established in several countries to record these manifestations, such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies registry,7,8 the COVIDSKIN registry of the French Dermatology Society,9 and the Italian registry.10 Highlighting the unprecedented number of scientific articles published on this new disease, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE search using the terms SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19, on April 6, 2023, revealed 351,596 articles; that is more than 300 articles published every day in this database alone, with a large number of them concerning the skin.

SKIN DISEASSES ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19

There are several types of COVID-19–related skin manifestations, depending on the circumstances of onset and the evolution of the pandemic.

Skin Manifestations Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The estimated incidence varies greatly according to the published series of patients, possibly depending on the geographic location. The estimated incidence seems lower in Asian countries, such as China (0.2%)5 and Japan (0.56%),11 compared with Europe (up to 20%).6 Skin manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection affect individuals of all ages, slightly more females, and are clinically polymorphous; some of them are associated with the severity of the infection.12 They may precede, accompany, or appear after the symptoms of COVID-19, most often within a month of the infection, of which they rarely are the only manifestation; however, their precise relationship to SARS-CoV-2 is not always well known. They have been classified according to their clinical presentation into several forms.13-15

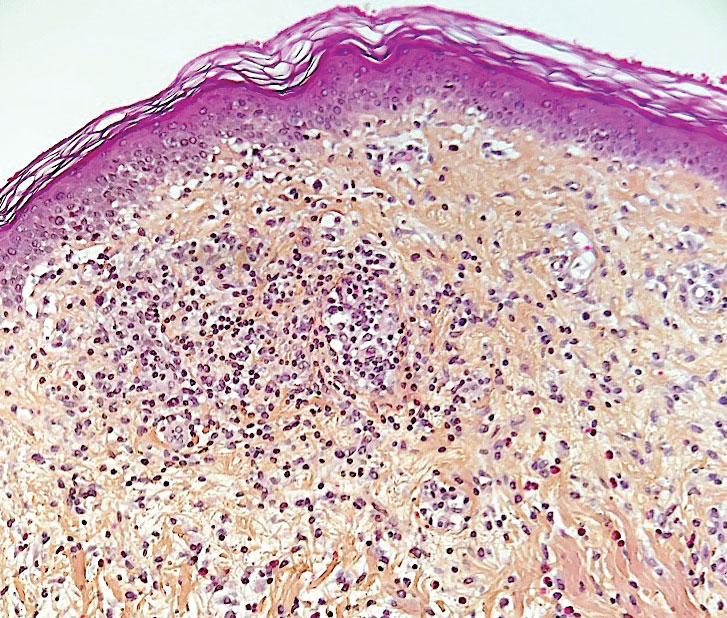

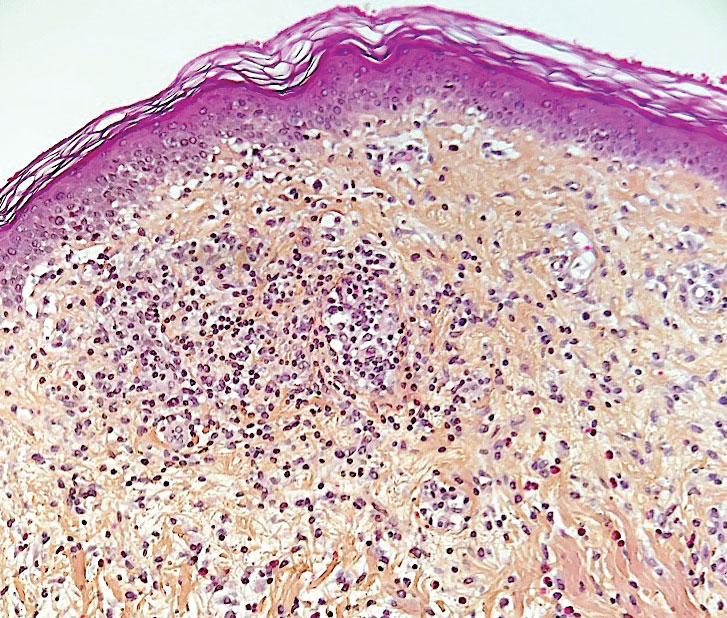

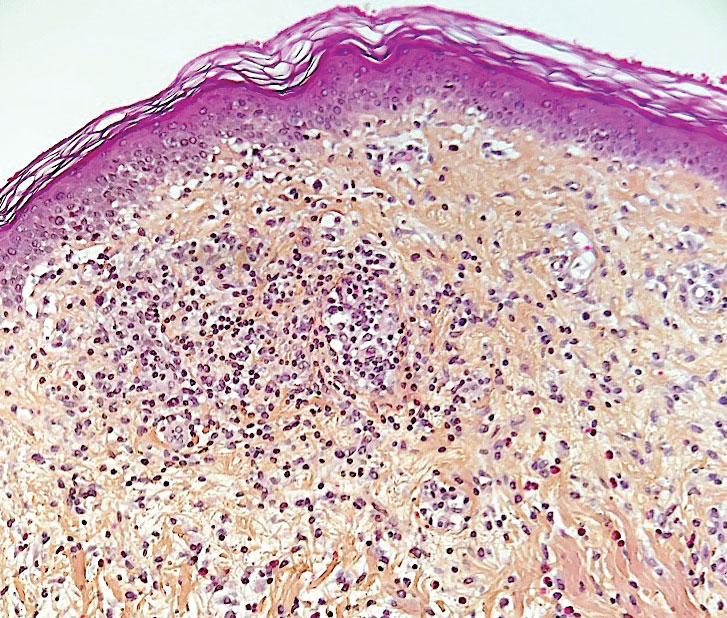

Morbilliform Maculopapular Eruption—Representing 16% to 53% of skin manifestations, morbilliform and maculopapular eruptions usually appear within 15 days of infection; they manifest with more or less confluent erythematous macules that may be hemorrhagic/petechial, and usually are asymptomatic and rarely pruritic. The rash mainly affects the trunk and limbs, sparing the face, palmoplantar regions, and mucous membranes; it appears concomitantly with or a few days after the first symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, respiratory symptoms), regresses within a few days, and does not appear to be associated with disease severity. The distinction from maculopapular drug eruptions may be subtle. Histologically, the rash manifests with a spongiform dermatitis (ie, variable parakeratosis; spongiosis; and a mixed dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils and histiocytes, depending on the lesion age)(Figure 1). The etiopathogenesis is unknown; it may involve immune complexes to SARS-CoV-2 deposited on skin vessels. Treatment is not mandatory; if necessary, local or systemic corticosteroids may be used.

Vesicular (Pseudovaricella) Rash—This rash accounts for 11% to 18% of all skin manifestations and usually appears within 15 days of COVID-19 onset. It manifests with small monomorphous or varicellalike (pseudopolymorphic) vesicles appearing on the trunk, usually in young patients. The vesicles may be herpetiform, hemorrhagic, or pruritic, and appear before or within 3 days of the onset of mild COVID-19 symptoms; they regress within a few days without scarring. Histologically, the lesions show basal cell vacuolization; multinucleated, dyskeratotic/apoptotic or ballooning/acantholytic epidermal keratinocytes; reticular degeneration of the epidermis; intraepidermal vesicles sometimes resembling herpetic vesicular infections or Grover disease; and mild dermal inflammation. There is no specific treatment.

Urticaria—Urticarial rash, or urticaria, represents 5% to 16% of skin manifestations; usually appears within 15 days of disease onset; and manifests with pruritic, migratory, edematous papules appearing mainly on the trunk and occasionally the face and limbs. The urticarial rash tends to be associated with more severe forms of the disease and regresses within a week, responding to antihistamines. Of note, clinically similar rashes can be caused by drugs. Histologically, the lesions show dermal edema and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, sometimes admixed with eosinophils.

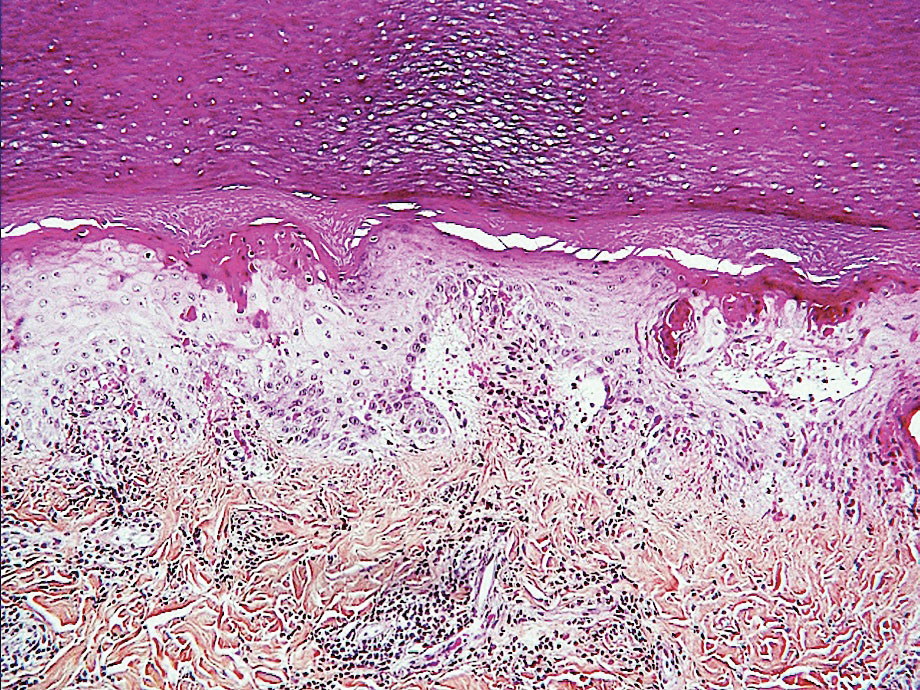

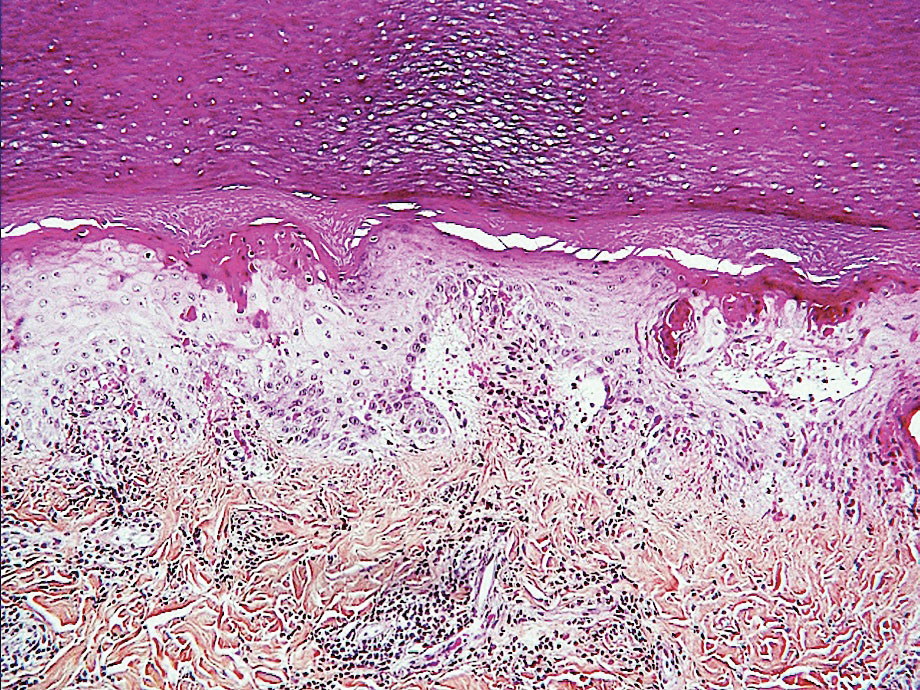

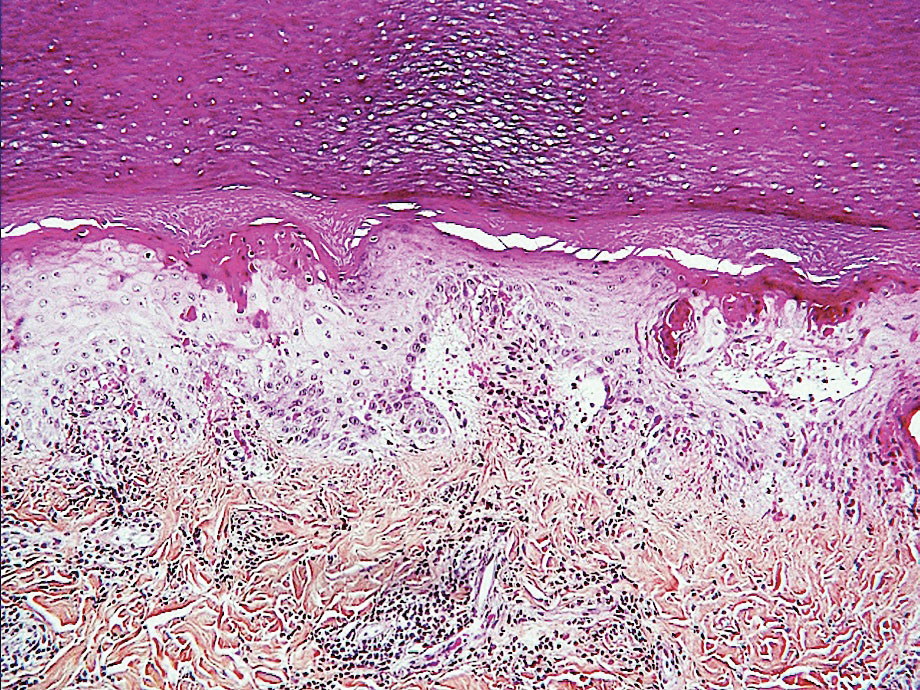

Chilblainlike Lesions—Chilblainlike lesions (CBLLs) account for 19% of skin manifestations associated with COVID-1913 and present as erythematous-purplish, edematous lesions that can be mildly pruritic or painful, appearing on the toes—COVID toes—and more rarely the fingers (Figure 2). They were seen epidemically during the first pandemic wave (2020 lockdown) in several countries, and clinically are very similar to, if not indistinguishable from, idiopathic chilblains, but are not necessarily associated with cold exposure. They appear in young, generally healthy patients or those with mild COVID-19 symptoms 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset. They regress spontaneously or under local corticosteroid treatment within a few days or weeks. Histologically, CBLLs are indistinguishable from chilblains of other origins, namely idiopathic (seasonal) ones. They manifest with necrosis of epidermal keratinocytes; dermal edema that may be severe, leading to the development of subepidermal pseudobullae; a rather dense perivascular and perieccrine gland lymphocytic infiltrate; and sometimes with vascular lesions (eg, edema of endothelial cells, microthromboses of dermal capillaries and venules, fibrinoid deposits within the wall of dermal venules)(Figure 3).16-18 Most patients (>80%) with CBLLs have negative serologic or polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2,19 which generated a lively debate about the role of SARS-CoV-2 in the genesis of CBLLs. According to some authors, SARS-CoV-2 plays no direct role, and CBLLs would occur in young people who sit or walk barefoot on cold floors at home during confinement.20-23 Remarkably, CBLLs appeared in patients with no history of chilblains during a season that was not particularly cold, namely in France or in southern California, where their incidence was much higher compared to the same time period of prior years. Some reports have supported a direct role for the virus based on questionable observations of the virus within skin lesions (eg, sweat glands, endothelial cells) by immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and/or in situ hybridization.17,24,25 A more satisfactory hypothesis would involve the role of a strong innate immunity leading to elimination of the virus before the development of specific antibodies via the increased production of type 1 interferon (IFN-1); this would affect the vessels, causing CBLLs. This mechanism would be similar to the one observed in some interferonopathies (eg, Aicardi-Goutières syndrome), also characterized by IFN-1 hypersecretion and chilblains.26-29 According to this hypothesis, CBLLs should be considered a paraviral rash similar to other skin manifestations associated with COVID-19.30

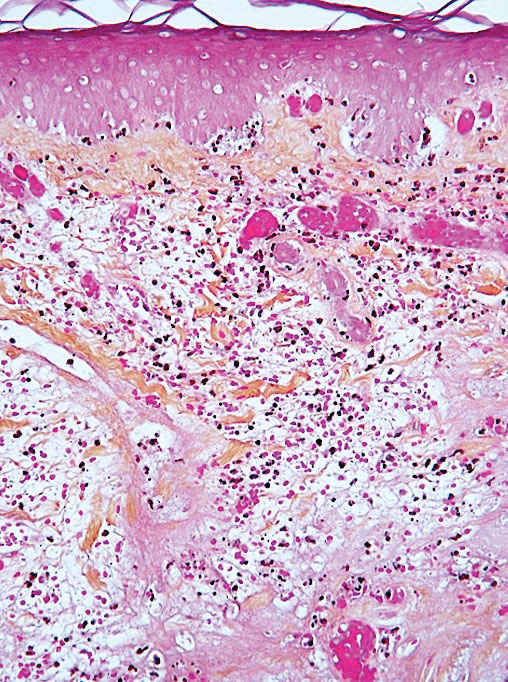

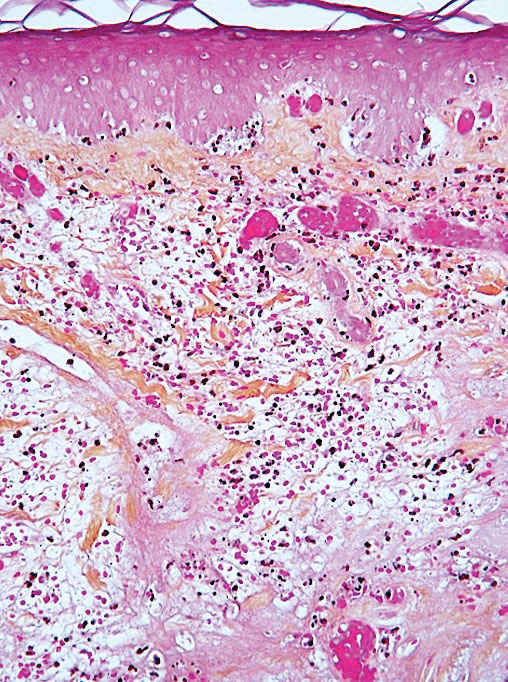

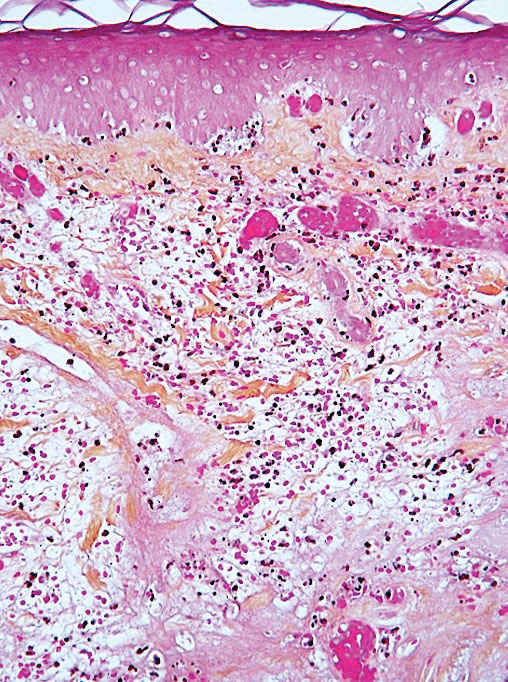

Acro-ischemia—Acro-ischemia livedoid lesions account for 1% to 6% of skin manifestations and comprise lesions of livedo (either reticulated or racemosa); necrotic acral bullae; and gangrenous necrosis of the extremities, especially the toes. The livedoid lesions most often appear within 15 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, and the purpuric lesions somewhat later (2–4 weeks); they mainly affect adult patients, last about 10 days, and are the hallmark of severe infection, presumably related to microthromboses of the cutaneous capillaries (endothelial dysfunction, prothrombotic state, elevated D-dimers). Histologically, they show capillary thrombosis and dermoepidermal necrosis (Figure 4).

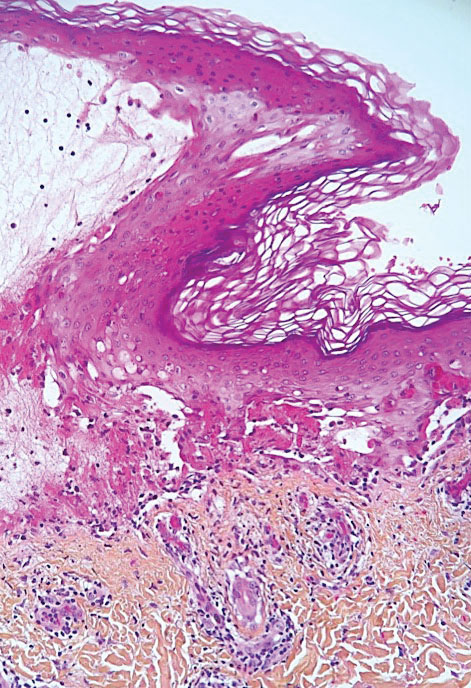

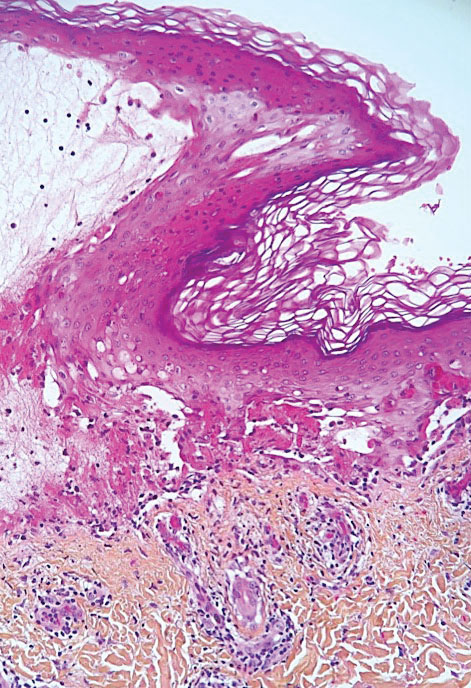

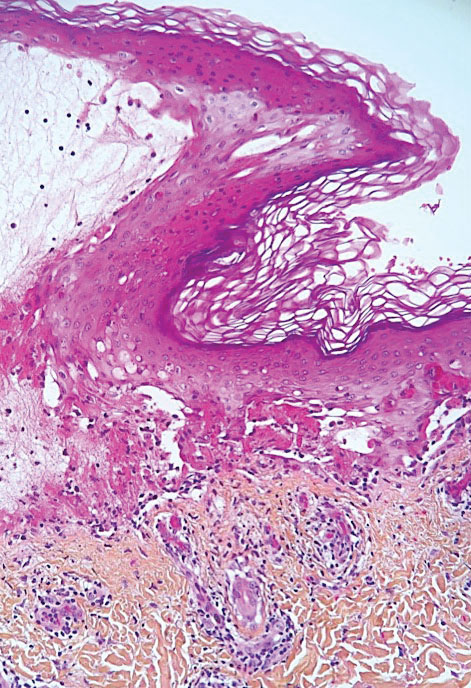

Other Reported Polymorphic or Atypical Rashes—Erythema multiforme–like eruptions may appear before other COVID-19 symptoms and manifest as reddish-purple, nearly symmetric, diffuse, occasionally targetoid bullous or necrotic macules. The eruptions mainly affect adults and most often are seen on the palms, elbows, knees, and sometimes the mucous membranes. The rash regresses in 1 to 3 weeks without scarring and represents a delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction. Histologically, the lesions show vacuolization of basal epidermal keratinocytes, keratinocyte necrosis, dermoepidermal detachment, a variably dense dermal T-lymphocytic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation (Figure 5).

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be generalized or localized. It manifests clinically by petechial/purpuric maculopapules, especially on the legs, mainly in elderly patients with COVID-19. Histologically, the lesions show necrotizing changes of dermal postcapillary venules, neutrophilic perivascular inflammation, red blood cell extravasation, and occasionally vascular IgA deposits by direct immunofluorescence examination. The course usually is benign.

The incidence of pityriasis rosea and of clinically similar rashes (referred to as “pityriasis rosea–like”) increased 5-fold during the COVID-19 pandemic.31,32 These dermatoses manifest with erythematous, scaly, circinate plaques, typically with an initial herald lesion followed a few days later by smaller erythematous macules. Histologically, the lesions comprise a spongiform dermatitis with intraepidermal exocytosis of red blood cells and a mild to moderate dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

Erythrodysesthesia, or hand-foot syndrome, manifests with edematous erythema and palmoplantar desquamation accompanied by a burning sensation or pain. This syndrome is known as an adverse effect of some chemotherapies because of the associated drug toxicity and sweat gland inflammation; it was observed in 40% of 666 COVID-19–positive patients with mild to moderate pneumonitis.33

“COVID nose” is a rare cutaneous manifestation characterized by nasal pigmentation comprising multiple coalescent frecklelike macules on the tip and wings of the nose and sometimes the malar areas. These lesions predominantly appear in women aged 25 to 65 years and show on average 23 days after onset of COVID-19, which is usually mild. This pigmentation is similar to pigmentary changes after infection with chikungunya; it can be treated with depigmenting products such as azelaic acid and hydroquinone cream with sunscreen use, and it regresses in 2 to 4 months.34

Telogen effluvium (excessive and temporary shedding of normal telogen club hairs of the entire scalp due to the disturbance of the hair cycle) is reportedly frequent in patients (48%) 1 month after COVID-19 infection, but it may appear later (after 12 weeks).35 Alopecia also is frequently reported during long (or postacute) COVID-19 (ie, the symptomatic disease phase past the acute 4 weeks’ stage of the infection) and shows a female predominance36; it likely represents the telogen effluvium seen 90 days after a severe illness. Trichodynia (pruritus, burning, pain, or paresthesia of the scalp) also is reportedly common (developing in more than 58% of patients) and is associated with telogen effluvium in 44% of cases. Several cases of alopecia areata (AA) triggered or aggravated by COVID-19 also have been reported37,38; they could be explained by the “cytokine storm” triggered by the infection, involving T and B lymphocytes; plasmacytoid dendritic cells; natural killer cells with oversecretion of IL-6, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor α, and IFN type I; and a cytotoxic reaction associated with loss of the immune privilege of hair follicles.

Nail Manifestations

The red half-moon nail sign is an asymptomatic purplish-red band around the distal margin of the lunula that affects some adult patients with COVID-19.39 It appears shortly after onset of symptoms, likely the manifestation of vascular inflammation in the nail bed, and regresses slowly after approximately 1 week.40 Beau lines are transverse grooves in the nail plate due to the temporary arrest of the proximal nail matrix growth accompanying systemic illnesses; they appear approximately 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of COVID-19.41 Furthermore, nail alterations can be caused by drugs used to treat COVID-19, such as longitudinal melanonychia due to treatment with hydroxychloroquine or fluorescence of the lunula or nail plate due to treatment with favipiravir.42

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) is clinically similar to Kawasaki disease; it typically affects children43 and more rarely adults with COVID-19. It manifests with fever, weakness, and biological inflammation and also frequently with skin lesions (72%), which are polymorphous and include morbilliform rash (27%); urticaria (24%); periorbital edema (24%); nonspecific erythema (21.2%); retiform purpura (18%); targetoid lesions (15%); malar rash (15.2%); and periareolar erythema (6%).44 Compared to Kawasaki disease, MIS affects slightly older children (mean age, 8.5 vs 3 years) and more frequently includes cardiac and gastrointestinal manifestations; the mortality rate also is slightly higher (2% vs 0.17%).45

Confirmed COVID-19 Infection

At the beginning of the pandemic, skin manifestations were reported in patients who were suspected of having COVID-19 but did not always have biological confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection due to the unavailability of diagnostic tests or the physical impossibility of testing. However, subsequent studies have confirmed that most of these dermatoses were indeed associated with COVID-19 infection.9,46 For example, a study of 655 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection reported maculopapular (38%), vascular (22%), urticarial (15%), and vesicular (15%) rashes; erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson–like syndrome (3%, often related to the use of hydroxychloroquine); generalized pruritus (1%); and MIS (0.5%). The study confirmed that CBLLs were mostly seen in young patients with mild disease, whereas livedo (fixed rash) and retiform purpura occurred in older patients with a guarded prognosis.46

Remarkably, most dermatoses associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported during the initial waves of the pandemic, which were due to the α and δ viral variants. These manifestations were reported more rarely when the ο variant was predominant, even though most patients (63%) who developed CBLLs in the first wave also developed them during the second pandemic wave.47 This decrease in the incidence of COVID-19–associated dermatoses could be because of the lower pathogenicity of the o variant,3 a lower tropism for the skin, and variations in SARS-CoV-2 antigenicity that would induce a different immunologic response, combined with an increasingly stronger herd immunity compared to the first pandemic waves achieved through vaccination and spontaneous infections in the population. Additional reasons may include different baseline characteristics in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (regarding comorbidities, disease severity, and received treatments), and the possibility that some of the initially reported COVID-19–associated skin manifestations could have been produced by different etiologic agents.48 In the last 2 years, COVID-19–related skin manifestations have been reported mainly as adverse events to COVID-19 vaccination.

CUTANEOUS ADVERSE EFFECTS OF DRUGS USED TO TREAT COVID-19

Prior to the advent of vaccines and specific treatments for SARS-CoV-2, various drugs were used—namely hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, and tocilizumab—that did not prove efficacious and caused diverse adverse effects, including cutaneous eruptions such as urticaria, maculopapular eruptions, erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, longitudinal melanonychia, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.49,50 Nirmatrelvir 150 mg–ritonavir 100 mg, which was authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, is a viral protease inhibitor blocking the replication of the virus. Ritonavir can induce pruritus, maculopapular rash, acne, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis; of note, these effects have been observed following administration of ritonavir for treatment of HIV at higher daily doses and for much longer periods of time compared with treatment of COVID-19 (600–1200 mg vs 200 mg/d, respectively). These cutaneous drug side effects are clinically similar to the manifestations caused either directly or indirectly by SARS-CoV-2 infection; therefore, it may be difficult to differentiate them.

DERMATOSES DUE TO PROTECTIVE DEVICES

Dermatoses due to personal protective equipment such as masks or face shields affected the general population and mostly health care professionals51; 54.4% of 879 health care professionals in one study reported such events.52 These dermatoses mainly include contact dermatitis of the face (nose, forehead, and cheeks) of irritant or allergic nature (eg, from preservatives releasing formaldehyde contained in masks and protective goggles). They manifest with skin dryness; desquamation; maceration; fissures; or erosions or ulcerations of the cheeks, forehead, and nose. Cases of pressure urticaria also have been reported. Irritant dermatitis induced by the frequent use of disinfectants (eg, soaps, hydroalcoholic sanitizing gels) also can affect the hands. Allergic hand dermatitis can be caused by medical gloves.

The term maskne (or mask acne) refers to a variety of mechanical acne due to the prolonged use of surgical masks (>4 hours per day for ≥6 weeks); it includes cases of de novo acne and cases of pre-existing acne aggravated by wearing a mask. Maskne is characterized by acne lesions located on the facial area covered by the mask (Figure 6). It is caused by follicular occlusion; increased sebum secretion; mechanical stress (pressure, friction); and dysbiosis of the microbiome induced by changes in heat, pH, and humidity. Preventive measures include application of noncomedogenic moisturizers or gauze before wearing the mask as well as facial cleansing with appropriate nonalcoholic products. Similar to acne, rosacea often is aggravated by prolonged wearing of surgical masks (mask rosacea).53,54

DERMATOSES REVEALED OR AGGRAVATED BY COVID-19

Exacerbation of various skin diseases has been reported after infection with SARS-CoV-2.55 Psoriasis and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau,56 which may progress into generalized, pustular, or erythrodermic forms,57 have been reported; the role of hydroxychloroquine and oral corticosteroids used for the treatment of COVID-19 has been suspected.57 Atopic dermatitis patients—26% to 43%—have experienced worsening of their disease after symptomatic COVID-19 infection.58 The incidence of herpesvirus infections, including herpes zoster, increased during the pandemic.59 Alopecia areata relapses occurred in 42.5% of 392 patients with preexisting disease within 2 months of COVID-19 onset in one study,60 possibly favored by the psychological stress; however, some studies have not confirmed the aggravating role of COVID-19 on alopecia areata.61 Lupus erythematosus, which may relapse in the form of Rowell syndrome,62 and livedoid vasculopathy63 also have been reported following COVID-19 infection.

SKIN MANIFESTATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19 VACCINES

In parallel with the rapid spread of COVID-19 vaccination,4 an increasing number of skin manifestations has been observed following vaccination; these dermatoses now are more frequently reported than those related to natural SARS-CoV-2 infection.64-70 Vaccine-induced skin manifestations have a reported incidence of approximately 4% and show a female predominance.65 Most of them (79%) have been reported in association with messenger RNA (mRNA)–based vaccines, which have been the most widely used; however, the frequency of side effects would be lower after mRNA vaccines than after inactivated virus-based vaccines. Eighteen percent occurred after the adenoviral vector vaccine, and 3% after the inactivated virus vaccine.70 Fifty-nine percent were observed after the first dose. They are clinically polymorphous and generally benign, regressing spontaneously after a few days, and they should not constitute a contraindication to vaccination.Interestingly, many skin manifestations are similar to those associated with natural SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, their frequency and severity does not seem to depend on whether the patients had developed skin reactions during prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. These reactions have been classified into several types:

• Immediate local reactions at the injection site: pain, erythema, or edema represent the vast majority (96%) of reactions to vaccines. They appear within 7 days after vaccination (average, 1 day), slightly more frequently (59%) after the first dose. They concern mostly young patients and are benign, regressing in 2 to 3 days.70

• Delayed local reactions: characterized by pain or pruritus, erythema, and skin induration mimicking cellulitis (COVID arm) and represent 1.7% of postvaccination reactions. They correspond to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction and appear approximately 7 days after vaccination, most often after the first vaccine dose (75% of cases), which is almost invariably mRNA based.70

• Urticarial reactions corresponding to an immediate (type 1) hypersensitivity reaction: constitute 1% of postvaccination reactions, probably due to an allergy to vaccine ingredients. They appear on average 1 day after vaccination, almost always with mRNA vaccines.70

• Angioedema: characterized by mucosal or subcutaneous edema and constitutes 0.5% of postvaccination reactions. It is a potentially serious reaction that appears on average 12 hours after vaccination, always with an mRNA-based vaccine.70

• Morbilliform rash: represents delayed hypersensitivity reactions (0.1% of postvaccination reactions) that appear mostly after the first dose (72%), on average 3 days after vaccination, always with an mRNA-based vaccine.70

• Herpes zoster: usually develops after the first vaccine dose in elderly patients (69% of cases) on average 4 days after vaccination and constitutes 0.1% of postvaccination reactions.71

• Bullous diseases: mainly bullous pemphigoid (90%) and more rarely pemphigus (5%) or bullous erythema pigmentosum (5%). They appear in elderly patients on average 7 days after vaccination and constitute 0.04% of postvaccination reactions.72

• Chilblainlike lesions: several such cases have been reported so far73; they constitute 0.03% of postvaccination reactions.70 Clinically, they are similar to those associated with natural COVID-19; they appear mostly after the first dose (64%), on average 5 days after vaccination with the mRNA or adenovirus vaccine, and show a female predominance. The appearance of these lesions in vaccinated patients, who are a priori not carriers of the virus, strongly suggests that CBLLs are due to the immune reaction against SARS-CoV-2 rather than to a direct effect of this virus on the skin, which also is a likely scenario with regards to other skin manifestations seen during the successive COVID-19 epidemic waves.73-75

• Reactions to hyaluronic acid–containing cosmetic fillers: erythema, edema, and potentially painful induration at the filler injection sites. They constitute 0.04% of postvaccination skin reactions and appear 24 hours after vaccination with mRNA-based vaccines, equally after the first or second dose.76

• Pityriasis rosea–like rash: most occur after the second dose of mRNA-based vaccines (0.023% of postvaccination skin reactions).70

• Severe reactions: these include acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis77 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.78 One case of each has been reported after the adenoviral vector vaccine 3 days after vaccination.

Other more rarely observed manifestations include reactivation/aggravation or de novo appearance of inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis,79,80 leukocytoclastic vasculitis,81,82 lymphocytic83 or urticarial84 vasculitis, Sweet syndrome,85 lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis,86,87 alopecia,37,88 infection with Trichophyton rubrum,89 Grover disease,90 and lymphomatoid reactions (such as recurrences of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas [CD30+], and de novo development of lymphomatoid papulosis).91

FINAL THOUGHTS

COVID-19 is associated with several skin manifestations, even though the causative role of SARS-CoV-2 has remained elusive. These dermatoses are highly polymorphous, mostly benign, and usually spontaneously regressive, but some of them reflect severe infection. They mostly were described during the first pandemic waves, reported in several national and international registries, which allowed for their morphological classification. Currently, cutaneous adverse effects of vaccines are the most frequently reported dermatoses associated with SARS-CoV-2, and it is likely that they will continue to be observed while COVID-19 vaccination lasts. Hopefully the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is near. In January 2023, the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee of the World Health Organization acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic may be approaching an inflexion point, and even though the event continues to constitute a public health emergency of international concern, the higher levels of population immunity achieved globally through infection and/or vaccination may limit the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on morbidity and mortality. However, there is little doubt that this virus will remain a permanently established pathogen in humans and animals for the foreseeable future.92 Therefore, physicians—especially dermatologists—should be aware of the various skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 so they can more efficiently manage their patients.

- Ashraf UM, Abokor AA, Edwards JM, et al. SARS-CoV-2, ACE2 expression, and systemic organ invasion. Physiol Genomics. 2021;53:51-60.

- Ganier C, Harun N, Peplow I, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression is detectable in keratinocytes, cutaneous appendages, and blood vessels by multiplex RNA in situ hybridization. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2022;35:219-223.

- Ulloa AC, Buchan SA, Daneman N, et al. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant severity in Ontario, Canada. JAMA. 2022;327:1286-1288.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://covid19.who.int

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19. clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-9: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129.

- Freeman EE, Chamberlin GC, McMahon DE, et al. Dermatology COVID-19 registries: updates and future directions. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:575-585.

- Guelimi R, Salle R, Dousset L, et al. Non-acral skin manifestations during the COVID-19 epidemic: COVIDSKIN study by the French Society of Dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E539-E541.

- Marzano AV, Genovese G, Moltrasio C, et al; Italian Skin COVID-19 Network of the Italian Society of Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 associated cutaneous manifestations: an Italian multicenter study of 200 adult patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1356-1363.

- Sugai T, Fujita Y, Inamura E, et al. Prevalence and patterns of cutaneous manifestations in 1245 COVID-19 patients in Japan: a single-centre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E522-E524.

- Holmes Z, Courtney A, Lincoln M, et al. Rash morphology as a predictor of COVID‐19 severity: a systematic review of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2:E120. doi:10.1002/ski2.120

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Garduño‑Soto M, Choreño-Parra, Cazarin-Barrientos Dermatological aspects of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection: mechanisms and manifestations. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:611-622.

- Huynh T, Sanchez-Flores X, Yau J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:277-286.

- Kanitakis J, Lesort C, Danset M, et al.

2020; 83:870-875. - Kolivras A, Thompson C, Pastushenko I, et al. A clinicopathological description of COVID-19-induced chilblains (COVID-toes) correlated with a published literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:17-28.

- Roca-Ginés J, Torres-Navarro I, Sánchez-Arráez J, et al. Assessment of acute acral lesions in a case series of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020;156:992-997.

- Le Cleach L, Dousset L, Assier H, et al; French Society of Dermatology. Most chilblains observed during the COVID-19 outbreak occur in patients who are negative for COVID-19 on polymerase chain reaction and serology testing. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:866-874.

- Discepolo V, Catzola A, Pierri L, et al. Bilateral chilblain-like lesions of the toes characterized by microvascular remodeling in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E2111369.

- Gehlhausen JR, Little AJ, Ko CJ, et al. Lack of association between pandemic chilblains and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2122090119.

- Neri, Virdi, Corsini, et al Major cluster of paediatric ‘true’ primary chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic: a consequence of lifestyle changes due to lockdown. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2630-2635.

- De Greef A, Choteau M, Herman A, et al. Chilblains observed during the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be distinguished from the classic, cold-related chilblains. Eur J Dermatol. 2022;32:377-383.

- Colmenero I, Santonja C, Alonso-Riaño M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of seven paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:729-737.

- Quintero-Bustos G, Aguilar-Leon D, Saeb-Lima M. Histopathological and immunohistochemical characterization of skin biopsies from 41 SARS-CoV-2 (+) patients: experience in a Mexican concentration institute: a case series and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:327-337.

- Arkin LM, Moon JJ, Tran JM, et al; COVID Human Genetic Effort. From your nose to your toes: a review of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic-associated pernio. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2791-2796.

- Frumholtz L, Bouaziz JD, Battistella M, et al; Saint-Louis CORE (COvid REsearch). Type I interferon response and vascular alteration in chilblain-like lesions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1176-1185.

- Hubiche T, Cardot-Leccia N, Le Duff F, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and interferon-alpha response characteristics of patients with chilblain-like lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:202-206.

- Lesort C, Kanitakis J, Villani A, et al. COVID-19 and outbreak of chilblains: are they related? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E757-E758.

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:819-820.

- Drago F, Broccolo F, Ciccarese G. Pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, and herpes zoster in the setting of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Dermatol. 2022;S0738-081X(22)00002-5.

- Dursun R, Temiz SA. The clinics of HHV-6 infection in COVID-19 pandemic: pityriasis rosea and Kawasaki disease. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13730.

- Nuno-Gonzalez A, Magaletsky K, Feito Rodríguez M, et al. Palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia: a diagnostic sign of COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e247-e249.

- Sil A, Panigrahi A, Chandra A, et al. “COVID nose”: a unique post-COVID pigmentary sequelae reminiscing Chik sign: a descriptive case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E419-E421.

- Starace M, Iorizzo M, Sechi A, et al. Trichodynia and telogen effluvium in COVID-19 patients: results of an international expert opinion survey on diagnosis and management. JAAD Int. 2021;5:11-18.

- Wong-Chew RM, Rodríguez Cabrera EX, Rodríguez Valdez CA, et al. Symptom cluster analysis of long COVID-19 in patients discharged from the Temporary COVID-19 Hospital in Mexico City. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2022;9:20499361211069264.

- Bardazzi F, Guglielmo A, Abbenante D, et al. New insights into alopecia areata during COVID-19 pandemic: when infection or vaccination could play a role. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1796-1798.

- Christensen RE, Jafferany M. Association between alopecia areata and COVID-19: a systematic review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:57-61.

- Wollina U, Kanitakis J, Baran R. Nails and COVID-19: a comprehensive review of clinical findings and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E15100.

- Méndez-Flores S, Zaladonis A, Valdes-Rodriguez R. COVID-19 and nail manifestation: be on the lookout for the red half-moon nail sign. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1414.

- Alobaida S, Lam JM. Beau lines associated with COVID-19. CMAJ. 2020;192:E1040.

- Durmaz EÖ, Demirciog˘lu D. Fluorescence in the sclera, nails, and teeth secondary to favipiravir use for COVID-19 infections. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:35-37.

- Brumfiel CM, DiLorenzo AM, Petronic-Rosic VM. Dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:329-333.

- Akçay N, Topkarcı Z, Menentog˘lu ME, et al. New dermatological findings of MIS-C: can mucocutaneous involvement be associated with severe disease course? Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:228-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.13819

- Vogel TP, Top KA, Karatzios C, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults (MIS-C/A): case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2021;39:3037-3049.

- Conforti C, Dianzani C, Agozzino M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in confirmed COVID-19 patients: a systematic review. Biology (Basel). 2020;9:449.

- Hubiche T, Le Duff F, Fontas E, et al. Relapse of chilblain-like lesions during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cohort follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:858-859.

- Fernandez-Nieto, Ortega-Quijano, Suarez-Valle, et al Lack of skin manifestations in COVID-19 hospitalized patients during the second epidemic wave in Spain: a possible association with a novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E183-E185.

- Martinez-LopezA, Cuenca-Barrales, Montero-Vilchezet al Review of adverse cutaneous reactions of pharmacologic interventions for COVID-19: a guide for the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1738-1748.

- Cutaneous side-effects of the potential COVID-19 drugs. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13476.

- Mawhirt SL, Frankel D, Diaz AM. Cutaneous manifestations in adult patients with COVID-19 and dermatologic conditions related to the COVID-19 pandemic in health care workers. Curr Allerg Asthma Rep. 2020;20:75.

- Nguyen C, Young FG, McElroy D, et al. Personal protective equipment and adverse dermatological reactions among healthcare workers: survey observations from the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:E29003.

- Rathi SK, Dsouza JM. Maskne: a new acne variant in COVID-19 era. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:552-555.

- Damiani G, Girono L, Grada A, et al. COVID-19 related masks increase severity of both acne (maskne) and rosacea (mask rosacea): multi-center, real-life, telemedical, and observational prospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14848.

- Aram K, Patil A, Goldust M, et al. COVID-19 and exacerbation of dermatological diseases: a review of the available literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E15113.

- Samotij D, Gawron E, Szcze˛ch J, et al. Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau evolving into generalized pustular psoriasis following COVID-19: a case report of a successful treatment with infliximab in combination with acitretin. Biologics. 2021;15:107-113.

- Demiri J, Abdo M, Tsianakas A. Erythrodermic psoriasis after COVID-19 [in German]. Hautarzt. 2022;73:156-159.

- de Wijs LEM, Joustra MM, Olydam JI, et al. COVID-19 in patients with cutaneous immune-mediated diseases in the Netherlands: real-world observational data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E173-E176.

- Marques NP, Maia CMF, Marques NCT, et al. Continuous increase of herpes zoster cases in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2022;133:612-614.

- Rinaldi F, Trink A, Giuliani G, et al. Italian survey for the evaluation of the effects of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on alopecia areata recurrence. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:339-345.

- Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Waskiel-Burnat A, et al. Mild-to-moderate COVID-19 is not associated with worsening of alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis of 32 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:723-725.

- Drenovska K, Shahid M, Mateeva V, et al. Case report: Rowell syndrome-like flare of cutaneous lupus erythematosus following COVID-19 infection. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:815743.

- Kawabe R, Tonomura K, Kotobuki Y, et al. Exacerbation of livedoid vasculopathy after coronavirus disease 2019. Eur J Dermatol. 2022;32:129-131. doi:10.1684/ejd.2022.4200

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Avallone G, Quaglino P, Cavallo F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1187-1204. doi:10.1111/ijd.16063

- Gambichler T, Boms S, Susok L, et al. Cutaneous findings following COVID-19 vaccination: review of world literature and own experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:172-180.

- Kroumpouzos G, Paroikaki ME, Yumeen S, et al. Cutaneous complications of mRNA and AZD1222 COVID-19 vaccines: a worldwide review. Microorganisms. 2022;10:624.

- Robinson L,Fu X,Hashimoto D, et al. Incidence of cutaneous reactions after messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines. 2021;

- Wollina U, Chiriac A, Kocic H, et al. Cutaneous and hypersensitivity reactions associated with COVID-19 vaccination: a narrative review. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2022;172:63-69.

- Wei TS. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186.

- Katsikas Triantafyllidis K, Giannos P, Mian IT, et al. Varicella zoster virus reactivation following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of case reports. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1013.

- Maronese CA, Caproni M, Moltrasio C, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with COVID-19 vaccines: an Italian multicentre study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:841506.

- Cavazos A, Deb A, Sharma U, et al. COVID toes following vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2022;35:476-479.

- Lesort C, Kanitakis J, Danset M, et al. Chilblain-like lesions after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: a case report suggesting that ‘COVID toes’ are due to the immune reaction to SARS-CoV-2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E630-E632.

- Russo R, Cozzani E, Micalizzi C, et al. Chilblain-like lesions after COVID-19 vaccination: a case series. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00711. doi:10.2340/actadv.v102.2076

- Ortigosa LCM, Lenzoni FC, Suárez MV, et al. Hypersensitivity reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal filler after COVID-19 vaccination: a series of cases in São Paulo, Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:268-270.

- Agaronov A, Makdesi C, Hall CS. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;16:96-97.

- Dash S, Sirka CS, Mishra S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1615-1617.

- Huang Y, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol 2022;47:153-155.

- Abdelmaksoud A, Wollina U, Temiz SA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination-induced cutaneous vasculitis: report of two new cases and literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15458.

- Fritzen M, Funchal GDG, Luiz MO, et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after exposure to COVID-19 vaccine. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:118-121.

- Vassallo C, Boveri E, Brazzelli V, et al. Cutaneous lymphocytic vasculitis after administration of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E15076.

- Nazzaro G, Maronese CA. Urticarial vasculitis following mRNA anti-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15282.

- Hoshina D, Orita A. Sweet syndrome after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 mRNA vaccine: a case report and literature review. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E175-E176.

- Lemoine C, Padilla C, Krampe N, et al. Systemic lupus erythematous after Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine: a case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41:1597-1601.

- Nguyen B, Lalama MJ, Gamret AC, et al. Cutaneous symptoms of connective tissue diseases after COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E238-E241.

- Gallo G, Mastorino L, Tonella L, et al. Alopecia areata after COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2022;11:129-132.

- Norimatsu Y, Norimatsu Y. A severe case of Trichophyton rubrum-caused dermatomycosis exacerbated after COVID-19 vaccination that had to be differentiated from pustular psoriasis. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2022;36:19-22.

- Yang K, Prussick L, Hartman R, et al. Acantholytic dyskeratosis post-COVID vaccination. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:E61-E63.

- Koumaki D, Marinos L, Nikolaou V, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) after AZD1222 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:900-902.

- World Health Organization. Statement on the fourteenth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Published January 30, 2023. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2023-statement-on-the-fourteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic

COVID-19 is a potentially severe systemic disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) caused fatal epidemics in Asia in 2002 to 2003 and in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, respectively. In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in patients with severe, sometimes fatal pneumonia of previously unknown origin; it rapidly spread around the world, and the World Health Organization declared the disease a pandemic on March 11, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus that is genetically related to the bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV; it is a single-stranded RNA virus of which several variants and subvariants exist. The SARS-CoV-2 viral particles bind via their surface spike protein (S protein) to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor present on the membrane of several cell types, including epidermal and adnexal keratinocytes.1,2 The α and δ variants, predominant from 2020 to 2021, mainly affected the lower respiratory tract and caused severe, potentially fatal pneumonia, especially in patients older than 65 years and/or with comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and (iatrogenic) immunosuppression. The ο variant, which appeared in late 2021, is more contagious than the initial variants, but it causes a less severe disease preferentially affecting the upper respiratory airways.3 As of April 5, 2023, more than 762,000,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, causing more than 6,800,000 deaths.4

Early studies from China describing the symptoms of COVID-19 reported a low frequency of skin manifestations (0.2%), probably because they were focused on the most severe disease symptoms.5 Subsequently, when COVID-19 spread to the rest of the world, an increasing number of skin manifestations were reported in association with the disease. After the first publication from northern Italy in spring 2020, which was specifically devoted to skin manifestations of COVID-19,6 an explosive number of publications reported a large number of skin manifestations, and national registries were established in several countries to record these manifestations, such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies registry,7,8 the COVIDSKIN registry of the French Dermatology Society,9 and the Italian registry.10 Highlighting the unprecedented number of scientific articles published on this new disease, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE search using the terms SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19, on April 6, 2023, revealed 351,596 articles; that is more than 300 articles published every day in this database alone, with a large number of them concerning the skin.

SKIN DISEASSES ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19

There are several types of COVID-19–related skin manifestations, depending on the circumstances of onset and the evolution of the pandemic.

Skin Manifestations Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The estimated incidence varies greatly according to the published series of patients, possibly depending on the geographic location. The estimated incidence seems lower in Asian countries, such as China (0.2%)5 and Japan (0.56%),11 compared with Europe (up to 20%).6 Skin manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection affect individuals of all ages, slightly more females, and are clinically polymorphous; some of them are associated with the severity of the infection.12 They may precede, accompany, or appear after the symptoms of COVID-19, most often within a month of the infection, of which they rarely are the only manifestation; however, their precise relationship to SARS-CoV-2 is not always well known. They have been classified according to their clinical presentation into several forms.13-15

Morbilliform Maculopapular Eruption—Representing 16% to 53% of skin manifestations, morbilliform and maculopapular eruptions usually appear within 15 days of infection; they manifest with more or less confluent erythematous macules that may be hemorrhagic/petechial, and usually are asymptomatic and rarely pruritic. The rash mainly affects the trunk and limbs, sparing the face, palmoplantar regions, and mucous membranes; it appears concomitantly with or a few days after the first symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, respiratory symptoms), regresses within a few days, and does not appear to be associated with disease severity. The distinction from maculopapular drug eruptions may be subtle. Histologically, the rash manifests with a spongiform dermatitis (ie, variable parakeratosis; spongiosis; and a mixed dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils and histiocytes, depending on the lesion age)(Figure 1). The etiopathogenesis is unknown; it may involve immune complexes to SARS-CoV-2 deposited on skin vessels. Treatment is not mandatory; if necessary, local or systemic corticosteroids may be used.

Vesicular (Pseudovaricella) Rash—This rash accounts for 11% to 18% of all skin manifestations and usually appears within 15 days of COVID-19 onset. It manifests with small monomorphous or varicellalike (pseudopolymorphic) vesicles appearing on the trunk, usually in young patients. The vesicles may be herpetiform, hemorrhagic, or pruritic, and appear before or within 3 days of the onset of mild COVID-19 symptoms; they regress within a few days without scarring. Histologically, the lesions show basal cell vacuolization; multinucleated, dyskeratotic/apoptotic or ballooning/acantholytic epidermal keratinocytes; reticular degeneration of the epidermis; intraepidermal vesicles sometimes resembling herpetic vesicular infections or Grover disease; and mild dermal inflammation. There is no specific treatment.

Urticaria—Urticarial rash, or urticaria, represents 5% to 16% of skin manifestations; usually appears within 15 days of disease onset; and manifests with pruritic, migratory, edematous papules appearing mainly on the trunk and occasionally the face and limbs. The urticarial rash tends to be associated with more severe forms of the disease and regresses within a week, responding to antihistamines. Of note, clinically similar rashes can be caused by drugs. Histologically, the lesions show dermal edema and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, sometimes admixed with eosinophils.

Chilblainlike Lesions—Chilblainlike lesions (CBLLs) account for 19% of skin manifestations associated with COVID-1913 and present as erythematous-purplish, edematous lesions that can be mildly pruritic or painful, appearing on the toes—COVID toes—and more rarely the fingers (Figure 2). They were seen epidemically during the first pandemic wave (2020 lockdown) in several countries, and clinically are very similar to, if not indistinguishable from, idiopathic chilblains, but are not necessarily associated with cold exposure. They appear in young, generally healthy patients or those with mild COVID-19 symptoms 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset. They regress spontaneously or under local corticosteroid treatment within a few days or weeks. Histologically, CBLLs are indistinguishable from chilblains of other origins, namely idiopathic (seasonal) ones. They manifest with necrosis of epidermal keratinocytes; dermal edema that may be severe, leading to the development of subepidermal pseudobullae; a rather dense perivascular and perieccrine gland lymphocytic infiltrate; and sometimes with vascular lesions (eg, edema of endothelial cells, microthromboses of dermal capillaries and venules, fibrinoid deposits within the wall of dermal venules)(Figure 3).16-18 Most patients (>80%) with CBLLs have negative serologic or polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2,19 which generated a lively debate about the role of SARS-CoV-2 in the genesis of CBLLs. According to some authors, SARS-CoV-2 plays no direct role, and CBLLs would occur in young people who sit or walk barefoot on cold floors at home during confinement.20-23 Remarkably, CBLLs appeared in patients with no history of chilblains during a season that was not particularly cold, namely in France or in southern California, where their incidence was much higher compared to the same time period of prior years. Some reports have supported a direct role for the virus based on questionable observations of the virus within skin lesions (eg, sweat glands, endothelial cells) by immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and/or in situ hybridization.17,24,25 A more satisfactory hypothesis would involve the role of a strong innate immunity leading to elimination of the virus before the development of specific antibodies via the increased production of type 1 interferon (IFN-1); this would affect the vessels, causing CBLLs. This mechanism would be similar to the one observed in some interferonopathies (eg, Aicardi-Goutières syndrome), also characterized by IFN-1 hypersecretion and chilblains.26-29 According to this hypothesis, CBLLs should be considered a paraviral rash similar to other skin manifestations associated with COVID-19.30

Acro-ischemia—Acro-ischemia livedoid lesions account for 1% to 6% of skin manifestations and comprise lesions of livedo (either reticulated or racemosa); necrotic acral bullae; and gangrenous necrosis of the extremities, especially the toes. The livedoid lesions most often appear within 15 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, and the purpuric lesions somewhat later (2–4 weeks); they mainly affect adult patients, last about 10 days, and are the hallmark of severe infection, presumably related to microthromboses of the cutaneous capillaries (endothelial dysfunction, prothrombotic state, elevated D-dimers). Histologically, they show capillary thrombosis and dermoepidermal necrosis (Figure 4).

Other Reported Polymorphic or Atypical Rashes—Erythema multiforme–like eruptions may appear before other COVID-19 symptoms and manifest as reddish-purple, nearly symmetric, diffuse, occasionally targetoid bullous or necrotic macules. The eruptions mainly affect adults and most often are seen on the palms, elbows, knees, and sometimes the mucous membranes. The rash regresses in 1 to 3 weeks without scarring and represents a delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction. Histologically, the lesions show vacuolization of basal epidermal keratinocytes, keratinocyte necrosis, dermoepidermal detachment, a variably dense dermal T-lymphocytic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation (Figure 5).

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be generalized or localized. It manifests clinically by petechial/purpuric maculopapules, especially on the legs, mainly in elderly patients with COVID-19. Histologically, the lesions show necrotizing changes of dermal postcapillary venules, neutrophilic perivascular inflammation, red blood cell extravasation, and occasionally vascular IgA deposits by direct immunofluorescence examination. The course usually is benign.

The incidence of pityriasis rosea and of clinically similar rashes (referred to as “pityriasis rosea–like”) increased 5-fold during the COVID-19 pandemic.31,32 These dermatoses manifest with erythematous, scaly, circinate plaques, typically with an initial herald lesion followed a few days later by smaller erythematous macules. Histologically, the lesions comprise a spongiform dermatitis with intraepidermal exocytosis of red blood cells and a mild to moderate dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

Erythrodysesthesia, or hand-foot syndrome, manifests with edematous erythema and palmoplantar desquamation accompanied by a burning sensation or pain. This syndrome is known as an adverse effect of some chemotherapies because of the associated drug toxicity and sweat gland inflammation; it was observed in 40% of 666 COVID-19–positive patients with mild to moderate pneumonitis.33

“COVID nose” is a rare cutaneous manifestation characterized by nasal pigmentation comprising multiple coalescent frecklelike macules on the tip and wings of the nose and sometimes the malar areas. These lesions predominantly appear in women aged 25 to 65 years and show on average 23 days after onset of COVID-19, which is usually mild. This pigmentation is similar to pigmentary changes after infection with chikungunya; it can be treated with depigmenting products such as azelaic acid and hydroquinone cream with sunscreen use, and it regresses in 2 to 4 months.34

Telogen effluvium (excessive and temporary shedding of normal telogen club hairs of the entire scalp due to the disturbance of the hair cycle) is reportedly frequent in patients (48%) 1 month after COVID-19 infection, but it may appear later (after 12 weeks).35 Alopecia also is frequently reported during long (or postacute) COVID-19 (ie, the symptomatic disease phase past the acute 4 weeks’ stage of the infection) and shows a female predominance36; it likely represents the telogen effluvium seen 90 days after a severe illness. Trichodynia (pruritus, burning, pain, or paresthesia of the scalp) also is reportedly common (developing in more than 58% of patients) and is associated with telogen effluvium in 44% of cases. Several cases of alopecia areata (AA) triggered or aggravated by COVID-19 also have been reported37,38; they could be explained by the “cytokine storm” triggered by the infection, involving T and B lymphocytes; plasmacytoid dendritic cells; natural killer cells with oversecretion of IL-6, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor α, and IFN type I; and a cytotoxic reaction associated with loss of the immune privilege of hair follicles.

Nail Manifestations

The red half-moon nail sign is an asymptomatic purplish-red band around the distal margin of the lunula that affects some adult patients with COVID-19.39 It appears shortly after onset of symptoms, likely the manifestation of vascular inflammation in the nail bed, and regresses slowly after approximately 1 week.40 Beau lines are transverse grooves in the nail plate due to the temporary arrest of the proximal nail matrix growth accompanying systemic illnesses; they appear approximately 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of COVID-19.41 Furthermore, nail alterations can be caused by drugs used to treat COVID-19, such as longitudinal melanonychia due to treatment with hydroxychloroquine or fluorescence of the lunula or nail plate due to treatment with favipiravir.42

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) is clinically similar to Kawasaki disease; it typically affects children43 and more rarely adults with COVID-19. It manifests with fever, weakness, and biological inflammation and also frequently with skin lesions (72%), which are polymorphous and include morbilliform rash (27%); urticaria (24%); periorbital edema (24%); nonspecific erythema (21.2%); retiform purpura (18%); targetoid lesions (15%); malar rash (15.2%); and periareolar erythema (6%).44 Compared to Kawasaki disease, MIS affects slightly older children (mean age, 8.5 vs 3 years) and more frequently includes cardiac and gastrointestinal manifestations; the mortality rate also is slightly higher (2% vs 0.17%).45

Confirmed COVID-19 Infection

At the beginning of the pandemic, skin manifestations were reported in patients who were suspected of having COVID-19 but did not always have biological confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection due to the unavailability of diagnostic tests or the physical impossibility of testing. However, subsequent studies have confirmed that most of these dermatoses were indeed associated with COVID-19 infection.9,46 For example, a study of 655 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection reported maculopapular (38%), vascular (22%), urticarial (15%), and vesicular (15%) rashes; erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson–like syndrome (3%, often related to the use of hydroxychloroquine); generalized pruritus (1%); and MIS (0.5%). The study confirmed that CBLLs were mostly seen in young patients with mild disease, whereas livedo (fixed rash) and retiform purpura occurred in older patients with a guarded prognosis.46

Remarkably, most dermatoses associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported during the initial waves of the pandemic, which were due to the α and δ viral variants. These manifestations were reported more rarely when the ο variant was predominant, even though most patients (63%) who developed CBLLs in the first wave also developed them during the second pandemic wave.47 This decrease in the incidence of COVID-19–associated dermatoses could be because of the lower pathogenicity of the o variant,3 a lower tropism for the skin, and variations in SARS-CoV-2 antigenicity that would induce a different immunologic response, combined with an increasingly stronger herd immunity compared to the first pandemic waves achieved through vaccination and spontaneous infections in the population. Additional reasons may include different baseline characteristics in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (regarding comorbidities, disease severity, and received treatments), and the possibility that some of the initially reported COVID-19–associated skin manifestations could have been produced by different etiologic agents.48 In the last 2 years, COVID-19–related skin manifestations have been reported mainly as adverse events to COVID-19 vaccination.

CUTANEOUS ADVERSE EFFECTS OF DRUGS USED TO TREAT COVID-19

Prior to the advent of vaccines and specific treatments for SARS-CoV-2, various drugs were used—namely hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, and tocilizumab—that did not prove efficacious and caused diverse adverse effects, including cutaneous eruptions such as urticaria, maculopapular eruptions, erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, longitudinal melanonychia, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.49,50 Nirmatrelvir 150 mg–ritonavir 100 mg, which was authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, is a viral protease inhibitor blocking the replication of the virus. Ritonavir can induce pruritus, maculopapular rash, acne, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis; of note, these effects have been observed following administration of ritonavir for treatment of HIV at higher daily doses and for much longer periods of time compared with treatment of COVID-19 (600–1200 mg vs 200 mg/d, respectively). These cutaneous drug side effects are clinically similar to the manifestations caused either directly or indirectly by SARS-CoV-2 infection; therefore, it may be difficult to differentiate them.

DERMATOSES DUE TO PROTECTIVE DEVICES

Dermatoses due to personal protective equipment such as masks or face shields affected the general population and mostly health care professionals51; 54.4% of 879 health care professionals in one study reported such events.52 These dermatoses mainly include contact dermatitis of the face (nose, forehead, and cheeks) of irritant or allergic nature (eg, from preservatives releasing formaldehyde contained in masks and protective goggles). They manifest with skin dryness; desquamation; maceration; fissures; or erosions or ulcerations of the cheeks, forehead, and nose. Cases of pressure urticaria also have been reported. Irritant dermatitis induced by the frequent use of disinfectants (eg, soaps, hydroalcoholic sanitizing gels) also can affect the hands. Allergic hand dermatitis can be caused by medical gloves.

The term maskne (or mask acne) refers to a variety of mechanical acne due to the prolonged use of surgical masks (>4 hours per day for ≥6 weeks); it includes cases of de novo acne and cases of pre-existing acne aggravated by wearing a mask. Maskne is characterized by acne lesions located on the facial area covered by the mask (Figure 6). It is caused by follicular occlusion; increased sebum secretion; mechanical stress (pressure, friction); and dysbiosis of the microbiome induced by changes in heat, pH, and humidity. Preventive measures include application of noncomedogenic moisturizers or gauze before wearing the mask as well as facial cleansing with appropriate nonalcoholic products. Similar to acne, rosacea often is aggravated by prolonged wearing of surgical masks (mask rosacea).53,54

DERMATOSES REVEALED OR AGGRAVATED BY COVID-19

Exacerbation of various skin diseases has been reported after infection with SARS-CoV-2.55 Psoriasis and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau,56 which may progress into generalized, pustular, or erythrodermic forms,57 have been reported; the role of hydroxychloroquine and oral corticosteroids used for the treatment of COVID-19 has been suspected.57 Atopic dermatitis patients—26% to 43%—have experienced worsening of their disease after symptomatic COVID-19 infection.58 The incidence of herpesvirus infections, including herpes zoster, increased during the pandemic.59 Alopecia areata relapses occurred in 42.5% of 392 patients with preexisting disease within 2 months of COVID-19 onset in one study,60 possibly favored by the psychological stress; however, some studies have not confirmed the aggravating role of COVID-19 on alopecia areata.61 Lupus erythematosus, which may relapse in the form of Rowell syndrome,62 and livedoid vasculopathy63 also have been reported following COVID-19 infection.

SKIN MANIFESTATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19 VACCINES

In parallel with the rapid spread of COVID-19 vaccination,4 an increasing number of skin manifestations has been observed following vaccination; these dermatoses now are more frequently reported than those related to natural SARS-CoV-2 infection.64-70 Vaccine-induced skin manifestations have a reported incidence of approximately 4% and show a female predominance.65 Most of them (79%) have been reported in association with messenger RNA (mRNA)–based vaccines, which have been the most widely used; however, the frequency of side effects would be lower after mRNA vaccines than after inactivated virus-based vaccines. Eighteen percent occurred after the adenoviral vector vaccine, and 3% after the inactivated virus vaccine.70 Fifty-nine percent were observed after the first dose. They are clinically polymorphous and generally benign, regressing spontaneously after a few days, and they should not constitute a contraindication to vaccination.Interestingly, many skin manifestations are similar to those associated with natural SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, their frequency and severity does not seem to depend on whether the patients had developed skin reactions during prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. These reactions have been classified into several types:

• Immediate local reactions at the injection site: pain, erythema, or edema represent the vast majority (96%) of reactions to vaccines. They appear within 7 days after vaccination (average, 1 day), slightly more frequently (59%) after the first dose. They concern mostly young patients and are benign, regressing in 2 to 3 days.70

• Delayed local reactions: characterized by pain or pruritus, erythema, and skin induration mimicking cellulitis (COVID arm) and represent 1.7% of postvaccination reactions. They correspond to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction and appear approximately 7 days after vaccination, most often after the first vaccine dose (75% of cases), which is almost invariably mRNA based.70

• Urticarial reactions corresponding to an immediate (type 1) hypersensitivity reaction: constitute 1% of postvaccination reactions, probably due to an allergy to vaccine ingredients. They appear on average 1 day after vaccination, almost always with mRNA vaccines.70

• Angioedema: characterized by mucosal or subcutaneous edema and constitutes 0.5% of postvaccination reactions. It is a potentially serious reaction that appears on average 12 hours after vaccination, always with an mRNA-based vaccine.70

• Morbilliform rash: represents delayed hypersensitivity reactions (0.1% of postvaccination reactions) that appear mostly after the first dose (72%), on average 3 days after vaccination, always with an mRNA-based vaccine.70

• Herpes zoster: usually develops after the first vaccine dose in elderly patients (69% of cases) on average 4 days after vaccination and constitutes 0.1% of postvaccination reactions.71

• Bullous diseases: mainly bullous pemphigoid (90%) and more rarely pemphigus (5%) or bullous erythema pigmentosum (5%). They appear in elderly patients on average 7 days after vaccination and constitute 0.04% of postvaccination reactions.72

• Chilblainlike lesions: several such cases have been reported so far73; they constitute 0.03% of postvaccination reactions.70 Clinically, they are similar to those associated with natural COVID-19; they appear mostly after the first dose (64%), on average 5 days after vaccination with the mRNA or adenovirus vaccine, and show a female predominance. The appearance of these lesions in vaccinated patients, who are a priori not carriers of the virus, strongly suggests that CBLLs are due to the immune reaction against SARS-CoV-2 rather than to a direct effect of this virus on the skin, which also is a likely scenario with regards to other skin manifestations seen during the successive COVID-19 epidemic waves.73-75

• Reactions to hyaluronic acid–containing cosmetic fillers: erythema, edema, and potentially painful induration at the filler injection sites. They constitute 0.04% of postvaccination skin reactions and appear 24 hours after vaccination with mRNA-based vaccines, equally after the first or second dose.76

• Pityriasis rosea–like rash: most occur after the second dose of mRNA-based vaccines (0.023% of postvaccination skin reactions).70

• Severe reactions: these include acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis77 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.78 One case of each has been reported after the adenoviral vector vaccine 3 days after vaccination.

Other more rarely observed manifestations include reactivation/aggravation or de novo appearance of inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis,79,80 leukocytoclastic vasculitis,81,82 lymphocytic83 or urticarial84 vasculitis, Sweet syndrome,85 lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis,86,87 alopecia,37,88 infection with Trichophyton rubrum,89 Grover disease,90 and lymphomatoid reactions (such as recurrences of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas [CD30+], and de novo development of lymphomatoid papulosis).91

FINAL THOUGHTS

COVID-19 is associated with several skin manifestations, even though the causative role of SARS-CoV-2 has remained elusive. These dermatoses are highly polymorphous, mostly benign, and usually spontaneously regressive, but some of them reflect severe infection. They mostly were described during the first pandemic waves, reported in several national and international registries, which allowed for their morphological classification. Currently, cutaneous adverse effects of vaccines are the most frequently reported dermatoses associated with SARS-CoV-2, and it is likely that they will continue to be observed while COVID-19 vaccination lasts. Hopefully the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is near. In January 2023, the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee of the World Health Organization acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic may be approaching an inflexion point, and even though the event continues to constitute a public health emergency of international concern, the higher levels of population immunity achieved globally through infection and/or vaccination may limit the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on morbidity and mortality. However, there is little doubt that this virus will remain a permanently established pathogen in humans and animals for the foreseeable future.92 Therefore, physicians—especially dermatologists—should be aware of the various skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 so they can more efficiently manage their patients.

COVID-19 is a potentially severe systemic disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) caused fatal epidemics in Asia in 2002 to 2003 and in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, respectively. In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in patients with severe, sometimes fatal pneumonia of previously unknown origin; it rapidly spread around the world, and the World Health Organization declared the disease a pandemic on March 11, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus that is genetically related to the bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV; it is a single-stranded RNA virus of which several variants and subvariants exist. The SARS-CoV-2 viral particles bind via their surface spike protein (S protein) to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor present on the membrane of several cell types, including epidermal and adnexal keratinocytes.1,2 The α and δ variants, predominant from 2020 to 2021, mainly affected the lower respiratory tract and caused severe, potentially fatal pneumonia, especially in patients older than 65 years and/or with comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and (iatrogenic) immunosuppression. The ο variant, which appeared in late 2021, is more contagious than the initial variants, but it causes a less severe disease preferentially affecting the upper respiratory airways.3 As of April 5, 2023, more than 762,000,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, causing more than 6,800,000 deaths.4

Early studies from China describing the symptoms of COVID-19 reported a low frequency of skin manifestations (0.2%), probably because they were focused on the most severe disease symptoms.5 Subsequently, when COVID-19 spread to the rest of the world, an increasing number of skin manifestations were reported in association with the disease. After the first publication from northern Italy in spring 2020, which was specifically devoted to skin manifestations of COVID-19,6 an explosive number of publications reported a large number of skin manifestations, and national registries were established in several countries to record these manifestations, such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies registry,7,8 the COVIDSKIN registry of the French Dermatology Society,9 and the Italian registry.10 Highlighting the unprecedented number of scientific articles published on this new disease, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE search using the terms SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19, on April 6, 2023, revealed 351,596 articles; that is more than 300 articles published every day in this database alone, with a large number of them concerning the skin.

SKIN DISEASSES ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19

There are several types of COVID-19–related skin manifestations, depending on the circumstances of onset and the evolution of the pandemic.

Skin Manifestations Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The estimated incidence varies greatly according to the published series of patients, possibly depending on the geographic location. The estimated incidence seems lower in Asian countries, such as China (0.2%)5 and Japan (0.56%),11 compared with Europe (up to 20%).6 Skin manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection affect individuals of all ages, slightly more females, and are clinically polymorphous; some of them are associated with the severity of the infection.12 They may precede, accompany, or appear after the symptoms of COVID-19, most often within a month of the infection, of which they rarely are the only manifestation; however, their precise relationship to SARS-CoV-2 is not always well known. They have been classified according to their clinical presentation into several forms.13-15

Morbilliform Maculopapular Eruption—Representing 16% to 53% of skin manifestations, morbilliform and maculopapular eruptions usually appear within 15 days of infection; they manifest with more or less confluent erythematous macules that may be hemorrhagic/petechial, and usually are asymptomatic and rarely pruritic. The rash mainly affects the trunk and limbs, sparing the face, palmoplantar regions, and mucous membranes; it appears concomitantly with or a few days after the first symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, respiratory symptoms), regresses within a few days, and does not appear to be associated with disease severity. The distinction from maculopapular drug eruptions may be subtle. Histologically, the rash manifests with a spongiform dermatitis (ie, variable parakeratosis; spongiosis; and a mixed dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils and histiocytes, depending on the lesion age)(Figure 1). The etiopathogenesis is unknown; it may involve immune complexes to SARS-CoV-2 deposited on skin vessels. Treatment is not mandatory; if necessary, local or systemic corticosteroids may be used.

Vesicular (Pseudovaricella) Rash—This rash accounts for 11% to 18% of all skin manifestations and usually appears within 15 days of COVID-19 onset. It manifests with small monomorphous or varicellalike (pseudopolymorphic) vesicles appearing on the trunk, usually in young patients. The vesicles may be herpetiform, hemorrhagic, or pruritic, and appear before or within 3 days of the onset of mild COVID-19 symptoms; they regress within a few days without scarring. Histologically, the lesions show basal cell vacuolization; multinucleated, dyskeratotic/apoptotic or ballooning/acantholytic epidermal keratinocytes; reticular degeneration of the epidermis; intraepidermal vesicles sometimes resembling herpetic vesicular infections or Grover disease; and mild dermal inflammation. There is no specific treatment.

Urticaria—Urticarial rash, or urticaria, represents 5% to 16% of skin manifestations; usually appears within 15 days of disease onset; and manifests with pruritic, migratory, edematous papules appearing mainly on the trunk and occasionally the face and limbs. The urticarial rash tends to be associated with more severe forms of the disease and regresses within a week, responding to antihistamines. Of note, clinically similar rashes can be caused by drugs. Histologically, the lesions show dermal edema and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, sometimes admixed with eosinophils.