User login

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

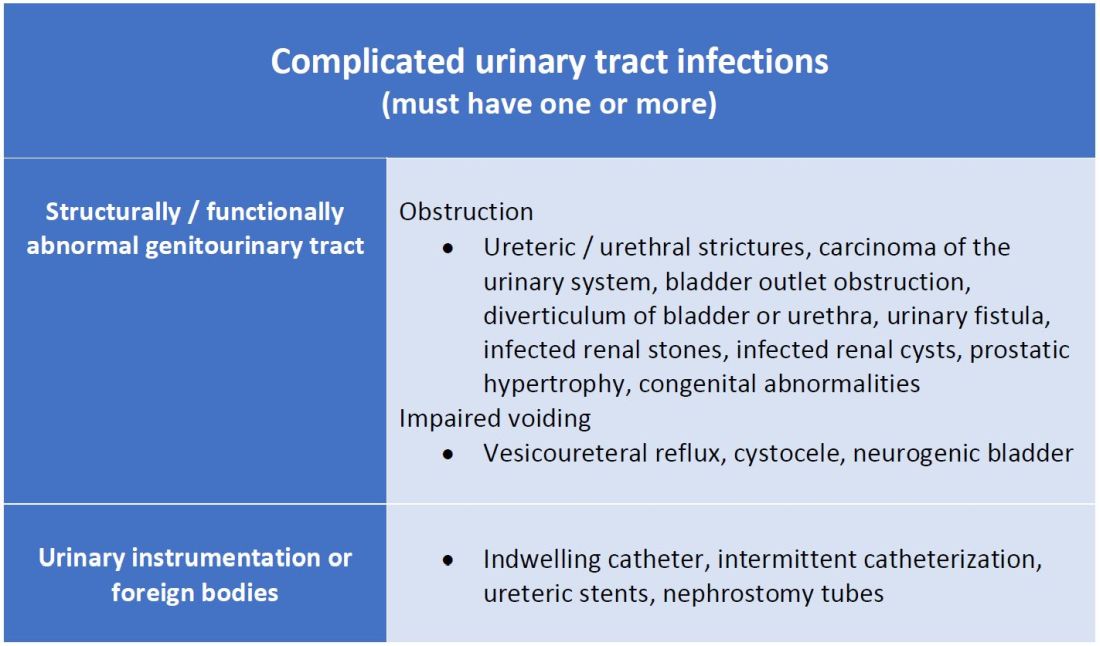

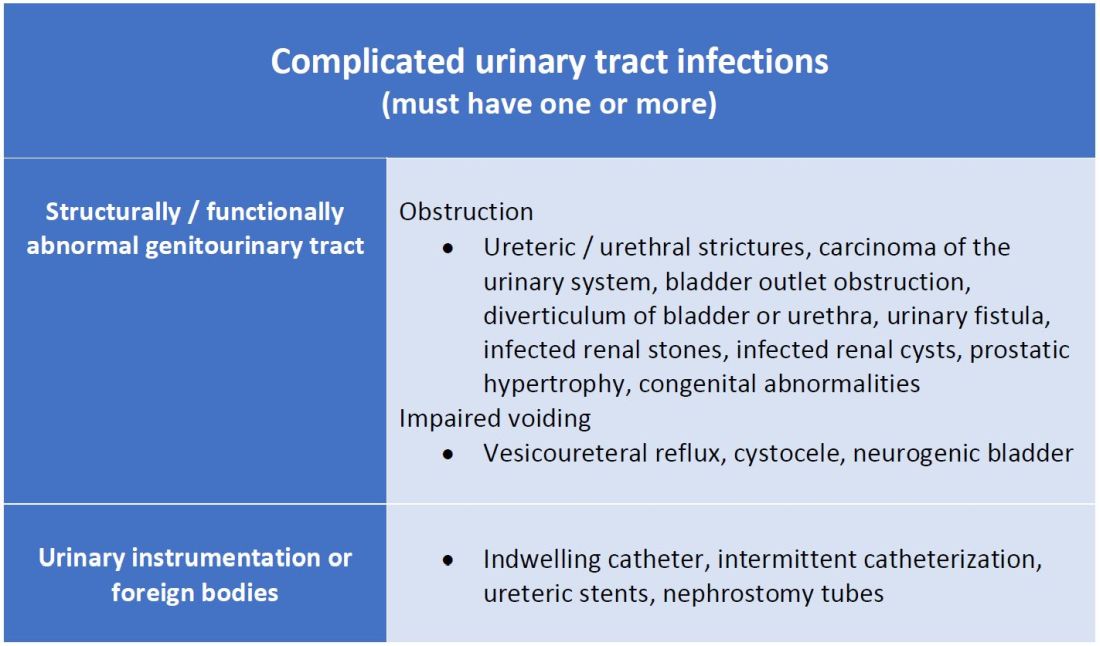

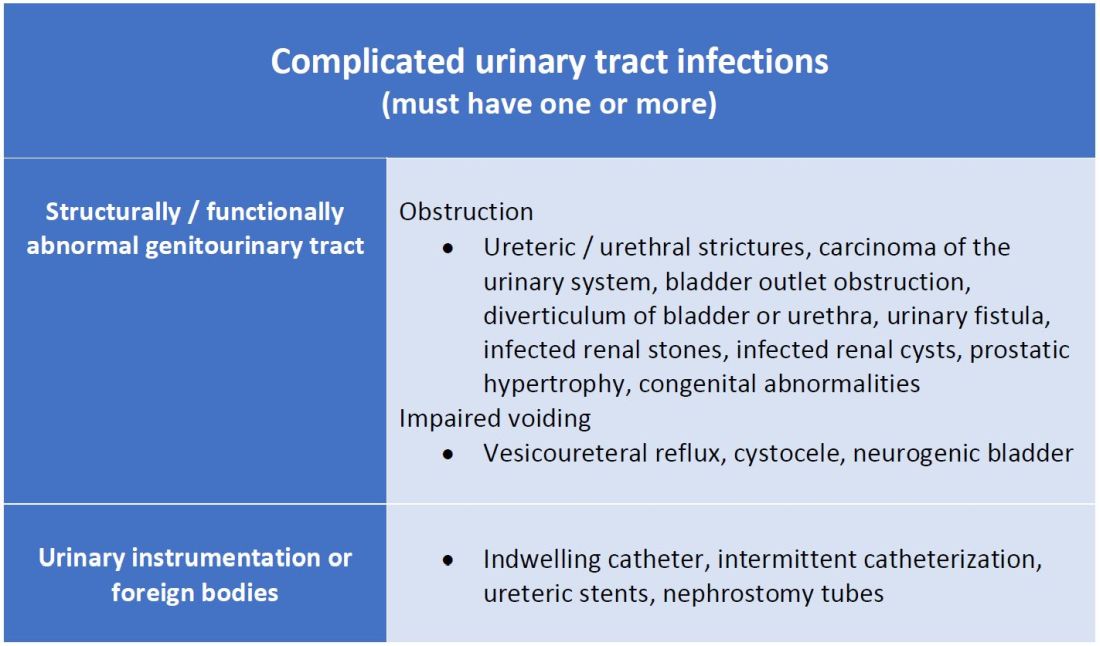

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

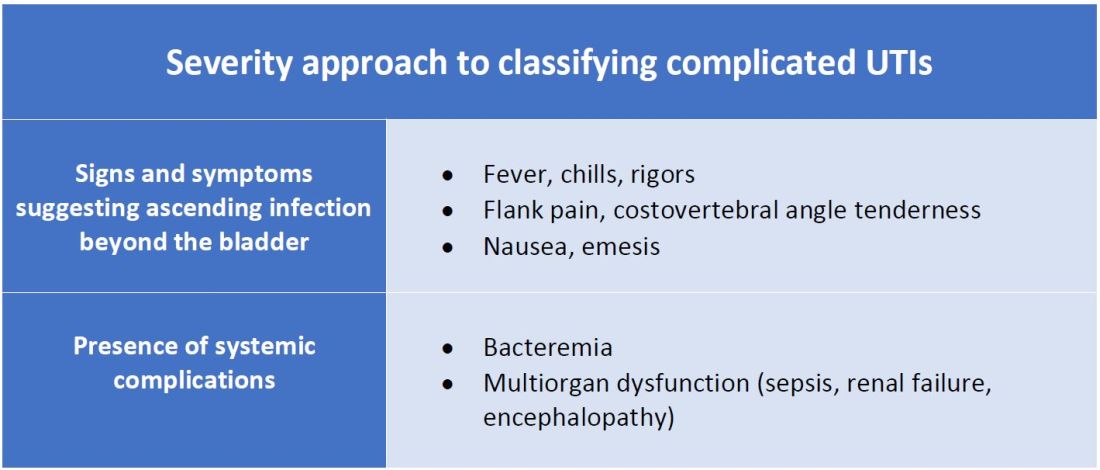

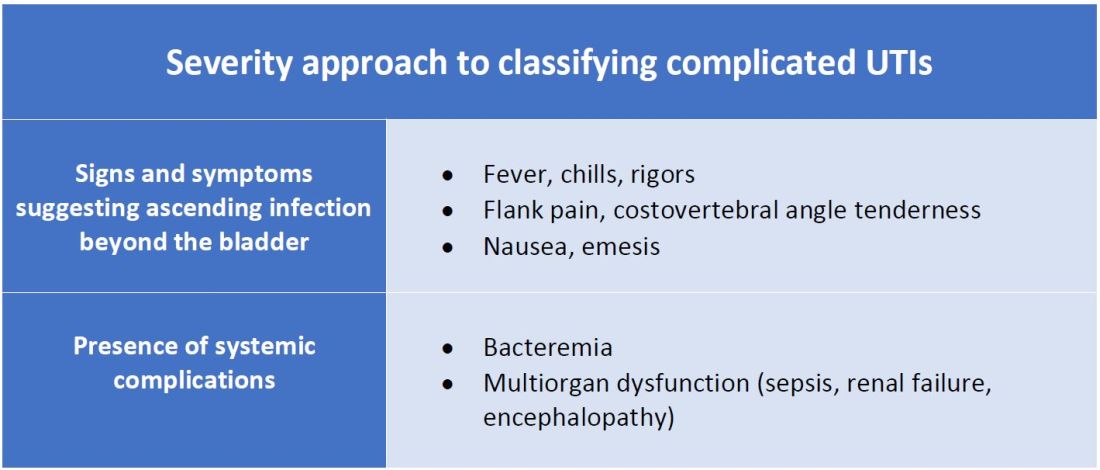

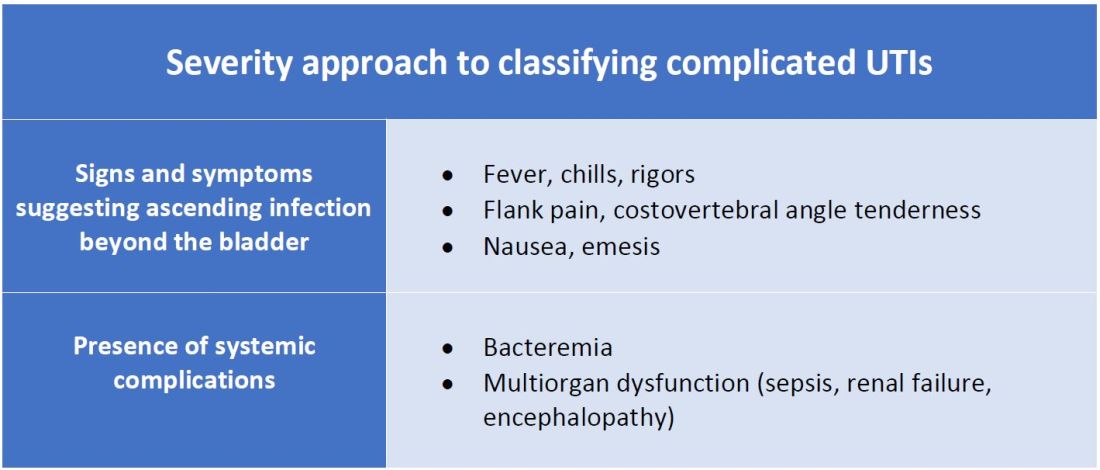

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.