User login

US veterans die by suicide at a higher rate than that of the civilian population, and are more likely to use a firearm as their lethal means.1 In 2017, 6,139 veterans died by suicide, about 17 per day.1 Nearly as many veterans die by suicide yearly as the total aggregate number of service members killed in action during the decades-long Iraq and Afghanistan operations.2 Veterans are more likely to own firearms than are civilians.3 Until June 2020, however, systemic efforts to address the use of firearms in suicide had been largely evaded, entangled in gun advocates’ assertion that veterans’ constitutional right to bear arms would be infringed.

That impasse changed with the President’s Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End the National Tragedy of Suicide (PREVENTS) task force report, released June 17, 2020.4 Although the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has pioneered initiatives to encourage safe firearm storage for at-risk veterans, and major public health organizations have endorsed the utility of lethal means safety strategies, the policy language of the Roadmap released by the White House is unprecedented. Lethal means safety refers to efforts aimed at increasing the time and distance needed to access suicide methods.

Among the report’s 10 recommendations, the Roadmap verified the link between, and the need to address, at-risk veterans and their access to firearms (the author was a minor consultant to a PREVENTS workgroup). The document states, “The science supporting lethal means safety is robust and compelling: enhancing safety measures specific to the availability and accessibility of potential lethal means saves lives. A key component of effective suicide prevention is voluntary reduction in the ability to access lethal means with respect to time, distance, and convenience, particularly during acute suicidal crises.”4 The report recommends widespread distribution of safety education materials that encourage at-risk individuals to temporarily transfer or store their guns safely, and the expansion of free or affordable options for storing weapons, among other recommendations.

This paper reviews the literature on the intersection of veterans, firearms, and suicide, then explores existing VA prevention initiatives aimed at reducing at-risk veterans’ access to lethal means and offers policy recommendations to expand efforts in the context of the PREVENTS Roadmap.

Veteran Suicide and Firearms

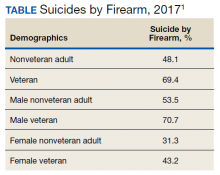

Firearms are, by far, the most common lethal means used by veterans who die by suicide. About 71% of male veteran suicide deaths and 43% of female veteran suicide deaths are with firearms, rates that far exceed those of nonveterans (Table).For all age groups, veterans are more likely to complete suicide by firearm than are nonveterans.5

Veteran suicide and gun ownership rates are highest in rural areas.6,7 When compared with veterans living in urban areas, veterans in rural areas are 20% more likely to die by suicide, with the excessive risk largely attributed to suicide by firearm.8

Access to firearms at home increases the risk of suicide. Individuals with any firearm at home are 3 times more likely to die by suicide than is a person with no firearms at home. The elevated suicide risk applies to other household members as well as the firearm owner.9-18 Survivors of suicide attempts using firearms report that the availability of guns at home is the primary reason for their method choice.19,20

There is a common misperception that people who are intent on suicide and are thwarted or survive an attempt using one method will try again with another.21 Suicidal crises often represent a conflicting wish to live or die,22 and approximately two-thirds of those who survive an attempt will never try again. About 23% reattempt nonfatally, and only 10% die by suicide.23-25 However, people who attempt suicide with a firearm usually won’t get a chance at a new start, because 90% of such acts are fatal.26

Although some suicide attempts might be contemplated or planned over an extended period, the decision is impulsive for most individuals. Surveys have found that many people who survive suicide attempts began the act only minutes or hours after making the decision to end their life.27-30 The high-risk, acute phase of many suicidal crises arise quickly and is fleeting.

Limiting the ease by which at-risk individuals can access firearms has been shown to prevent suicide. In 2006, the overall suicide rate in Israel dropped 40% when the Israeli Defense Forces began requiring soldiers to store their firearms on base before going on weekend leave.Since then, the suicide rate has declined even further.31,32

Delaying Access to Firearms for At-Risk Veterans

Among veterans, 45% own ≥ 1 firearms (47% male and 24% female veterans vs 30% male and 12% female nonveterans).3 Many veteran firearm owners (34% male and 13% female) store ≥ 1 gun loaded and unlocked; 44% store a firearm either loaded or unlocked. Only 23% safely store their firearms unloaded and locked at home. Storing ≥ 1 firearm loaded and unlocked is more likely among veterans who reside in rural areas, separated from service before 2002, and report personal protection as the primary reason for ownership.33

Because evidence shows that delaying access to firearms—especially by transferring them out of the home—saves lives, many US health organizations have advocated for strategies that promote evaluation of firearm access and counseling safe storage for individuals at risk for suicide. These organizations include the US Office of the Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Public Health Association.34-36

Some health care systems—notably Kaiser Permanente and Henry Ford Health Systems—implemented protocols for lethal means assessment and counseling for behavioral health patients.37,38 Washington state requires specific health professionals to enroll in suicide prevention training that includes content on the risk of imminent harm by lethal means.39 California is designing a curriculum on counseling patients to reduce firearm injury for physicians and other health care practitioners (HCPs).40

The scope of these efforts, however, pale in comparison with the VA’s comprehensive, innovative lethal means safety approach. Since 2012, VA’s Suicide Prevention Program has distributed free firearm cable locks to veterans who request them. The VA has created lethal means public service announcements, social media messages, and websites.41-44 The VA distributes firearm and medication safe storage practice resource kits to its primary care, mental health and women’s health clinics, and Vet Centers, that include brochures, large poster cards, stickers, exam room posters, and provider pocket cards. VA developed an online lethal means safety counseling training that 20,000 VA HCPs have taken, and is moving toward a revamped mandatory training for VA’s mental health, pain, primary care, and emergency department (ED) providers and Veterans Crisis Line responders. VA offers free, individualized lethal means risk management consultation to all clinicians who work with veterans.45 VA includes lethal means safety procedures in its National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide,VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline,and VA Suicide Risk Evaluation and Suicide Prevention Safety Planrequired of clinicians.46-48

The VA also added public health strategies that promote safe storage practices for veterans through a partnership with the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF; the firearm industry trade association) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP).49 Collectively, these organizations cobranded an educational, training, and resource toolkit to foster community coalitions and gun retailer projects that encourage veterans to securely store firearms.50 The VA partnered with NSSF to post billboards in 8 states, encouraging storing firearms responsibly to prevent suicide. VA invited states and cities in the Governor/Mayoral Challenge to Prevent Suicide (joint VA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration endeavors) to develop plans for messaging regarding enhanced lethal means safety processes. The VA collaborated with local firearm advocates in community prevention pilot projects and in a “Together with Veterans” dissemination of material and outreach to rural veterans.51 Along with AFSP, VA hosted conferences for HCPs, policy makers, and stakeholders about innovations related to lethal means safety.52 In May 2020, the VA cosponsored a COVID-19 suicide prevention video with the United States Concealed Carry Association, NSSF, and AFSP, including ways that the firearm industry, gun owners, and their families can help.53

These programs are promising, and the Roadmap’s emphatic endorsement of lethal means safety approaches will accelerate advances. However, the Roadmap’s omissions are consequential. By focusing on population interventions, the document is silent about VA-specific or veteran-specific firearm access strategies. The means safety work of VA’s Suicide Prevention Program Office is scarcely recognized. Further, it stops short of specific legislative initiatives, making aspirational recommendations instead.

This paper will list proposed policy actions to bolster the acceptability and practice of lethal means safety with veterans. They cover an entire range of possibilities, from putting more teeth into the Roadmap’s population-wide interventions to initiatives tailored to veterans. Responsibility for leading and funding the changes would reside in a mix of Congress and state legislatures, the VA, and health system accreditation bodies. Although there is solid evidence that lethal means safety prevents suicide, it is unknown how these approaches affect firearm storage behaviors or suicide rates;therefore, the policy actions should come with federal and state funds for rigorous evaluation.54

Recommended Actions to Further Promote Safe Storage

Develop Campaigns to Shift Cultural Norms for Firearm Storage During Crises

National campaigns have been shown to be highly effective in changing injurious behaviors. Alliances and resources with regard to lethal means safety could be assembled, including federal funds for a campaign to shift social norms for firearm storage conversations and behaviors during crises. This campaign should be modeled after the “friends don’t let friends drive drunk” and “designated driver” campaigns that empower family and friends to protect one another. Since those campaigns’ inception in 1982, two-thirds of Americans have tried to prevent someone from driving after drinking,and traffic deaths involving alcohol-impaired crashes have decreased 65%.55,56

The comparable lethal means safety enterprise would encourage friends and family to talk with those in crisis about storing firearms safely. The campaign must use spokespersons who have strong respect and credibility among firearm owners, such as the NSSF and the United States Concealed Carry Association who have developed firearm suicide prevention websites and videos.57,58

The emphasis is that it’s a personal strength—not a failing—to talk to friends, loved ones, or counselors about storing guns until a crisis passes. Some of the current phrasing includes: “Hey, let me hold your guns for a while,” “People who love guns, love you,” and “Have a brave conversation.” 59-61

The national campaign should attempt to correct the inaccurate beliefs that suicide death always is the result of mental illness and is inevitable once seriously contemplated. In fact, more than half of the individuals who die by suicide have no diagnosed mental health condition.62 Other crises, such as with finances, relationships, or physical health, might be more contributory. These myths about suicide and mental illness weaken public and policy maker interest in solutions aimed toward accessing lethal means.

Facilitate Temporary Storage Out of the Home

The PREVENTS Roadmap Supplemental Materials concluded, “Moving firearms out of the home is generally cited as the safest, most desirable option; this can include storage with another person or at a location like a firearm range, armory, pawn shop, self-storage unit, or law enforcement agency, although state laws for firearm transfers may affect what options are legal.”63 This goal could be achieved by establishing grants to gun shops and ranges to offer free lockers for voluntary safe harbor.

The creation of free community lockers was a top PREVENTS recommendation. Likewise, the congressionally chartered COVER (Creating Options for Veterans' Expedited Recovery) Commission recommended grants “to further support the development of voluntary firearm safe storage options across the country.”64 Federal and state grants might resolve hesitations cited by retailers by covering all expenses for lockers, labor, and insurance for theft/damage/liability.65,66 Locker use would be free to the user, eliminating all financial barriers, although it is unknown whether monetary incentives change storage behaviors. Many firearm owners report that private gun shops or ranges are more acceptable than police stations for storage. If retailers come on board, changes in cultural storage norms might be expedited. An additional benefit could be reduction of accidental firearm fatalities in the home. States that have legal impediments to returning firearms to their owners could modify laws to achieve popular acceptance.

Congress could consider funding a national, easily accessible, public online directory of locations for out-of-home firearm storage, with staff to update the site. Colorado, Maryland, and Washington have developed online maps showing locations of firearm outlets and law enforcement agencies willing to consider temporary storage.67 A site directory for every state would simplify the process for individuals and family members seeking to temporarily and voluntarily store guns offsite during a crisis. Online directories have been backed by firearm groups,although their effect on storage behavior is not known.68State governments should strive to make it easier to quickly transfer firearms temporarily to trusted individuals in situations of imminent suicide risk. Rapid transfer of firearms to friends or family could effectively separate lethal means from individuals during a crisis. However, some state laws that require background checks whenever a gun is transferred might delay such transfers.69 Only a few states have legal exemptions that could expedite temporary transfers when it’s potentially lifesaving.

Improve In-Home Safe Storage Options

Out-of-home transfer of firearms might not be acceptable or feasible for some veterans. Accordingly, there is need for improved options for safer in-home storage, especially because of frequent unsafe storage practices among veterans. The VA could consider sponsoring another open-innovation Gun Safety Matters Challenge like the one it held in 2018 for in-home firearm storage technology that could prevent suicide.70 Further innovation and bringing winning entries to market has great potential.

Require Enhanced Lethal Means Safety Standards and Training

Broader lethal means safety competence is needed, both in the VA where modest levels of training has been implemented and in the community among Veterans Community Care Program (VCCP) HCPs where it hasn’t. Oversight for enhanced standards and training—as well as of all lethal means initiatives and their program evaluations—might best be accomplished by establishing a separate VA Suicide Prevention Program lethal means safety team. Veteran firearm suicide is a significant problem that warrants its own discrete, permanent VA team (although joining with the US Department of Defense might be advantageous). The VA Suicide Prevention Program has been the industry leader and innovator in this field and should be conferred continued stewardship going forward.

The VA is moving toward requiring lethal means safety counseling training for mental health, pain, primary care, women’s health, ED providers, and Veterans Crisis Line responders.

VCCP HCPs, however, have no required training in lethal means safety counseling or even in basic suicide risk identification and intervention, and the Roadmap did not stipulate that this deficiency should be remedied. Surveys have revealed that community HCPs rarely screen or counsel their patients—even those at high risk—about firearm safety.71 A bill was introduced in Congress August 21, 2020, to expand VA suicide prevention training with firearms community input on cultural competency components and mandate that VA and VCCP providers, and some others with frequent contact with veterans, receive this training.72

Training should be obligatory for VA and VCCP HCPs and trainees most likely to interface with at-risk veterans, including those working in mental health, primary care, pain, women’s health, and ED. Training also should include geriatrics, extended care, and oncology providers because most older adults who die by firearm suicide have physical health problems but no known mental illness.73-75 Lethal means safety counseling training has been shown to improve HCPs’ knowledge about the relationship between access to lethal means and suicide, and confidence in and frequency of having lethal means safety counseling conversations.76 Likewise, training should include peer counselors; veterans are receptive to fellow veterans raising the topic of safe storage.56,77 If feasible, the training should include time to rehearse skills shown to motivate behavior change among patients.

The VA should aim to improve semiyearly clinical pertinence reviews and safety plans for VA and VCCP mental health providers. VA could conduct clinical pertinence reviews that ascertain whether a suicide assessment is recorded in the health record, and when a patient is at elevated risk, whether a lethal means safety assessment and plan is documented.

VA’s safety plan template, although best practice, covers only the initial steps to take when suicide potential is identified. A standard for follow-up is needed. If an at-risk patient agrees to take a safe storage action, subsequent contact HCPs need to ask and document what action was performed. This action will help ensure that at-risk patients with ready access do not fall through the cracks. This suggestion lends itself to studying changes in veterans’ storage habits after intervention.

I also recommend that health care accrediting bodies include lethal means safety assessment, counseling, and follow up as a suicide prevention standard. This recommendation applies to more than just the VA health care system and recognizes that modifying accrediting body standards is an expeditious way to drive change in health care. The accreditation standards of the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities for behavioral health and opioid treatment programs, and of the Joint Commission for medical centers do not require lethal means safety assessment and intervention.78,79

Conclusions

Suicide prevention requires a multimodal approach, and attention to firearms access must become a more salient component. The high rate of veteran suicides involving firearms requires far-reaching interventions at societal, institutional, community, family, and individual levels. With the link between ready access to firearms and suicide supported by research and now firmly recognized by the PREVENTS Roadmap, we have a fresh opportunity to reduce suicide among veterans. Efforts must move vigorously forward until it is commonplace for veterans—and anyone—at risk of suicide to voluntarily reduce immediate access to firearms.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 2019. Accessed August 20, 2020.

2. US Department of Defense. Casualty status. https://www.defense.gov/casualty.pdf. Published August 17, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020.

3. Cleveland EC, Azreal D, Simonetti JA, Miller M. Firearm ownership among American veterans: findings from the 2015 National Firearm Survey. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4:33. doi:10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PREVENTS: the President’s roadmap to empower veterans and end a national tragedy of suicide. https://www.va.gov/PREVENTS/docs/PRE-007-The-PREVENTS-Roadmap-1-2_508.pdf. Published June 17, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020.

5. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N. Firearm suicide among veterans in the general population: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Trauma. 2009;67(3):503-507. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b36521

6. Miller M, Barber C, White RA, Azrael D. Firearms and suicide in the United States: is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):946-955. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt197

7. Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack, SP, Haileyesus, T, Kresnow-Sedacca M. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death—United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(18):1-16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1

8. McCarthy JF, Blow FC, Ignacio RV, Ilgen MA, Austin KL, Valenstein M. Suicide among patients in the Veterans Affairs Health System: rural-urban differences in rates, risks and methods. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S111-S117. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300463

9. RAND Corporation. The relationship between firearm availability and suicide. https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/essays/firearm-availability-suicide.html. Published March 2, 2018. Accessed August 20, 2020.

10. Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):101-110. doi:10.7326/M13-1301

11. Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Swanson SA, et al. Handgun ownership and suicide in California. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2220-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1916744

12. Miller M, Hemenway D. The relationship between firearms and suicide: a review of the literature. Aggression Violent Behav. 1999;4(1):59-75. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00057-8

13. Brent DA. Firearms and suicide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;932:225-239. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05808.x

14. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Connor K, Eberly S, Cox C, Caine ED. Access to firearms and risk for suicide in middle aged and older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):407-416. doi:10.1176/appi.ajgp.10.4.407

15. Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. doi:10.1001/jama.293.6.707

16. Simonetti JA, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Limiting access to firearms as a suicide prevention strategy among adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195400. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5400

17. Dempsey CL, Benedek DM, Zuromski KL, et al. Association of firearm use, accessibility, and storage practices with suicide risk among US army soldiers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195383. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5383

18. Wiebe DJ. Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med. 41(6):771-782. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.187

19. de Moore GM, Plew JD, Bray KM, Snars JN. Survivors of self-inflicted firearm injury: a liaison psychiatry perspective. Med J Aust. 1994;160(7):421-425. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1994.tb138267.x

20. Peterson LG, Peterson M, O’Shanick GJ, Swann A. Self-inflicted gunshot wounds: lethality of method versus intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(2):228-231. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.2.228

21. Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Belief in the inevitability of suicide: results from a national survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(1):1-11. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.1.1

22. Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughan S, Wertenberger, EG. The ebb and flow of the wish to live and the wish to die among suicidal military personnel. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:58-66. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.049

23. O’Donnell I, Arthur AJ, Farmer RD. A follow-up study of attempted railway suicides. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(3):437-442. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90444-8

24. Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and nonfatal repetition of self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193-199. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.3.193

25. Seiden RH. Where are they now? A follow-up study of suicide attempters from the Golden Gate Bridge. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1978;8(4):203-216. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1978.tb00587.x

26. Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide case fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):885-895. doi:10.7326/M19-1324

27. Disenhammer EA, Ing CM, Strauss R, Kemmler G, Hinterhuber H, Weiss EM. The duration of the suicidal process: how much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt? J Clin Psych. 2009;70(1):19-24. doi:10.4088/JCP.07m03904

28. Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow M, O’Carrol, PW. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32(suppl 1):49-59. doi:10.1521/suli.32.1.5.49.24212

29. Williams CL, Davidson JA, Montgomery I. Impulsive suicidal behavior. J Clin Psychol. 1980;36(1):90-94. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198001)36:1<90::aid-jclp2270360104>3.0.co;2-f

30. Drum, DJ, Brownson, CB, Denmark, AB, Smith, SE. New data on the nature of suicidal crises in college students: shifting the paradigm. Professional Psychol: Res Pract. 2009;40(3):213-222. doi:10.1037/a0014465

31. Lubin G, Werbeloff N, Halperin D, Shmushkevitch M, Weise M, Knobler H. Decrease in suicide rates after a change of policy reducing access to firearms in adolescents: a naturalistic epidemiological study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(5):421-424. doi:10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.421

32. Shelef L, Tatsa-Laur L, Derazne E, Mann JJ, Fruchter E. An effective suicide prevention program in the Israeli Defense Forces: a cohort study. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:37-43. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.10.004

33. Simonetti JA, Azrael D, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Miller M. Firearm storage practices among American veterans. Amer J Prev Med. 2018;55(4):445-454. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.014

34. Office of the Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives for action: a report of the U.S. Surgeon General and of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23136686 Published September 2012. Accessed August 18, 2020.

35. Stone D, Holland KM, Bartholow B, Crosby AE, Davis S, Wilkins N. Preventing suicide: a technical package of policies, programs, and practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

36. American Public Health Association. Reducing suicides by firearms. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/28/reducing-suicides-by-firearms. Published November 13, 2018. Accessed August 18, 2020.

37. Coffey MJ, Coffey CE, Ahmedani BK. Suicide in a health maintenance organization population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(3):294-296. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2440

38. Boggs JM, Beck A, Ritzwoller DP, Battaglia C, Anderson HD, Lindrooth RC. A quasi-experimental analysis of lethal means assessment and risk for subsequent suicide attempts and deaths. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1709-1714. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05641-4

39. Washington State Health Assessment 2018. Suicide & safe storage of firearms https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1000/SHA-SuicideandSafeStorageofFirearms.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2020.

40. UC Davis Health Newsroom. First-in-the-nation gun violence prevention training program for health professionals established at UC Davis Health. https://health.ucdavis.edu/health-news/newsroom/first-in-the-nation-gun-violence-prevention-training-program-for-health-professionals-established-at-uc-davis-health/2019/10. Published October 15, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

41. Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Lethal means safety & suicide prevention. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/lethalmeanssafety/index.asp. Updated February 1, 2018. Accessed August 18, 2020.

42. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Reducing firearm & other household safety risks for veterans and their families. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Brochure-for-Veterans-Means-Safety-Messaging_508_CLEARED_11-15-19.pdf. Published July 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

43. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Means safety messaging for clinical staff. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Pocket-Card-for-Clinicians-Means-Safety-Messaging_508_CLEARED_9-3-19.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2020.

44. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Lethal means counseling: recommendations for providers. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/LethalMeansProviders20200527508.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

45. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Supporting providers who serve veterans. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn19/consult. Updated August 3, 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing veteran suicide 2018-2028. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2020.

47. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines: assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb. Updated July 30, 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

48. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Developing a safety plan. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/vasafetyplancolor.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed August 18, 2020.

49. Lemle RB. VA forges an historic partnership with the National Shooting Sports Foundation and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to prevent veteran suicide. Fed Pract. 2019;36(2):18-24.

50. US Department of Veterans Affairs, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, National Shooting Sports Foundation. Suicide prevention is everyone’s business: a toolkit for safe firearm storage in your community. https://project2025.afsp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Toolkit_Safe_Firearm_Storage_CLEARED_508_2-24-20.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2020.

51. Montheith, LL, Wendleton, L, Bahraini, NH, Matarazzo, BB, Brimner, G, Mohatt, NV. Together with veterans: VA national strategy alignment and lessons learned from community-based suicide prevention for rural veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50(3):588-600. doi:10.1111/sltb.12613. Epub 2020 Jan 16

52. Gordon S. VA pioneering efforts to reduce veteran suicide from firearms. http://beyondchron.org/va-pioneering-efforts-to-reduce-veteran-suicide-from-firearms. Published March 10, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020.

53. Johnson A. Protecting mental health and preventing suicide during COVID-19. https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/76827/mental-health-and-suicide-prevention-during-covid-19. Published July 14, 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

54. Betz ME, Anestis MD. Firearms, pesticides, and suicide: a look back for a way forward. Prev Med. 2020;138:106144. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106144

55. Buckley, L, Chapman, RL, and Lewis, I. A systematic review of intervening to prevent driving while intoxicated: The problem of driving while intoxicated (DWI), Substance Use & Misuse. 2016; 51(1): 104-112. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1090452

56. National Safety Council. Injury facts. motor vehicle safety issues. https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/motor-vehicle-safety-issues/alcohol-impaired-driving. Accessed August 2020.

57. Crifasi CK, Doucette ML, McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Storage practices of US gun owners in 2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):532-537. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304262

58. National Shooting Sports Foundation. Suicide prevention program for retailers and ranges. https://www.nssf.org/safety/suicide-prevention. Accessed August 18, 2020.

59. Pallin R, Siry B, Azrael D, et al. “Hey, let me hold your guns for a while”: a qualitative study of messaging for firearm suicide prevention. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(3):259-269. doi:10.1002/bsl.2393

60. Oregon Firearm Safety. http://oregonfirearmsafety.org. Accessed August 18, 2020.

61. National Shooting Sports Foundation. Suicide prevention toolkit items. https://www.nssf.org/safety/suicide-prevention/suicide-prevention-toolkit. Accessed August 18, 2020.

62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide rising across the US. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html. Updated June 7, 2018. Accessed August 18, 2020.

63. U.S Department of Veterans Affairs. PREVENTS: executive order 13861. https://www.va.gov/PREVENTS/EO-13861.asp. Updated August 13, 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

64. COVER Commission. Creating Options for Veterans’ Expedited Recovery (COVER) Commission Final Report. https://www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Published January 24, 2020. Accessed August 18, 2020.

65. Pierpoint LA, Tung GJ, Brooks-Russell A, Brandspigel S, Betz M, Runyan CW. Gun retailers as storage partners for suicide prevention: what barriers need to be overcome? Inj Prev. 2019;25(suppl 1):i5-i8. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042700

66. Gibbons MJ, Fan MD, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Rivara FP. Legal liability for returning firearms to suicidal persons who voluntarily surrender them in 50 US states. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):685-688. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305545

67. Kelly T, Brandspigel S, Polzer E, Betz ME. Firearm storage maps: a pragmatic approach to reduce firearm suicide during times of risk. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(5):351-353. doi:10.7326/M19-2944

68. Edwards C. This new gun storage map is designed to save lives in Colorado. https://bearingarms.com/cam-e/2019/08/27/new-gun-storage-map-designed-save-lives-colorado. Published August 27, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

69. McCourt AD, Vernick JS, Betz ME, Brandspigel S, Runyan CW. Temporary transfer of firearms from the home to prevent suicide: legal obstacles and recommendations. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):96-101. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5704

70. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Aimed at suicide prevention, VA shares winners of its ‘Gun Safety Matters Challenge.” https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/50233/aimed-suicide-prevention-va-shares-winners-gun-safety-matters-challenge. Published July 9, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

71. Roszko PJD, Ameli J, Carter PM, Cunningham RM, Ranney ML. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):87-110. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxv005

72. Lethal Means Safety Training Act. HR 8084, 116th Cong. 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/8084/text. Accessed August 25, 2020.

73. Boggs JM, Simon GE, Ahmedani BK, Peterson E, Hubley S, Beck A. The association of firearm suicide with mental illness, substance use conditions, and previous suicide attempts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):287-288. doi:10.7326/L17-0111

74. Schmutte TJ, Wilkinson ST. Suicide in older adults with and without known mental illness: results from the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2003-2016. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(4):584-590. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.11.001

75. Morin RT, Li Y, Mackin RS, Whooley MA, Conwell Y, Byers AL. Comorbidity profiles identified in older primary care patients who attempt suicide. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(12):2553-2559. doi:10.1111/jgs.16126

76. Roszko PJD, Ameli J, Carter PM, Cunningham RM, Ranney, ML. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):87-110. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxv005

77. Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. 7th annual IAVA member survey: the most comprehensive look into the lives of post-9/11. https://iava.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/IAVA-MemberSurvey-single-pgs1.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2020.

78. CARF International. CARF adds screening for suicide risk to its assessment standards. http://www.carf.org/universal-suicide-screening-standards. Published May 2, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

79. Paul S. National Patient Safety Goal expands focus on suicide prevention. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/blogs/dateline-tjc/2019/01/national-patient-safety-goal-expands-focus-on-suicide-prevention/. Published January 24, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2020.

US veterans die by suicide at a higher rate than that of the civilian population, and are more likely to use a firearm as their lethal means.1 In 2017, 6,139 veterans died by suicide, about 17 per day.1 Nearly as many veterans die by suicide yearly as the total aggregate number of service members killed in action during the decades-long Iraq and Afghanistan operations.2 Veterans are more likely to own firearms than are civilians.3 Until June 2020, however, systemic efforts to address the use of firearms in suicide had been largely evaded, entangled in gun advocates’ assertion that veterans’ constitutional right to bear arms would be infringed.

That impasse changed with the President’s Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End the National Tragedy of Suicide (PREVENTS) task force report, released June 17, 2020.4 Although the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has pioneered initiatives to encourage safe firearm storage for at-risk veterans, and major public health organizations have endorsed the utility of lethal means safety strategies, the policy language of the Roadmap released by the White House is unprecedented. Lethal means safety refers to efforts aimed at increasing the time and distance needed to access suicide methods.

Among the report’s 10 recommendations, the Roadmap verified the link between, and the need to address, at-risk veterans and their access to firearms (the author was a minor consultant to a PREVENTS workgroup). The document states, “The science supporting lethal means safety is robust and compelling: enhancing safety measures specific to the availability and accessibility of potential lethal means saves lives. A key component of effective suicide prevention is voluntary reduction in the ability to access lethal means with respect to time, distance, and convenience, particularly during acute suicidal crises.”4 The report recommends widespread distribution of safety education materials that encourage at-risk individuals to temporarily transfer or store their guns safely, and the expansion of free or affordable options for storing weapons, among other recommendations.

This paper reviews the literature on the intersection of veterans, firearms, and suicide, then explores existing VA prevention initiatives aimed at reducing at-risk veterans’ access to lethal means and offers policy recommendations to expand efforts in the context of the PREVENTS Roadmap.

Veteran Suicide and Firearms

Firearms are, by far, the most common lethal means used by veterans who die by suicide. About 71% of male veteran suicide deaths and 43% of female veteran suicide deaths are with firearms, rates that far exceed those of nonveterans (Table).For all age groups, veterans are more likely to complete suicide by firearm than are nonveterans.5

Veteran suicide and gun ownership rates are highest in rural areas.6,7 When compared with veterans living in urban areas, veterans in rural areas are 20% more likely to die by suicide, with the excessive risk largely attributed to suicide by firearm.8

Access to firearms at home increases the risk of suicide. Individuals with any firearm at home are 3 times more likely to die by suicide than is a person with no firearms at home. The elevated suicide risk applies to other household members as well as the firearm owner.9-18 Survivors of suicide attempts using firearms report that the availability of guns at home is the primary reason for their method choice.19,20

There is a common misperception that people who are intent on suicide and are thwarted or survive an attempt using one method will try again with another.21 Suicidal crises often represent a conflicting wish to live or die,22 and approximately two-thirds of those who survive an attempt will never try again. About 23% reattempt nonfatally, and only 10% die by suicide.23-25 However, people who attempt suicide with a firearm usually won’t get a chance at a new start, because 90% of such acts are fatal.26

Although some suicide attempts might be contemplated or planned over an extended period, the decision is impulsive for most individuals. Surveys have found that many people who survive suicide attempts began the act only minutes or hours after making the decision to end their life.27-30 The high-risk, acute phase of many suicidal crises arise quickly and is fleeting.

Limiting the ease by which at-risk individuals can access firearms has been shown to prevent suicide. In 2006, the overall suicide rate in Israel dropped 40% when the Israeli Defense Forces began requiring soldiers to store their firearms on base before going on weekend leave.Since then, the suicide rate has declined even further.31,32

Delaying Access to Firearms for At-Risk Veterans

Among veterans, 45% own ≥ 1 firearms (47% male and 24% female veterans vs 30% male and 12% female nonveterans).3 Many veteran firearm owners (34% male and 13% female) store ≥ 1 gun loaded and unlocked; 44% store a firearm either loaded or unlocked. Only 23% safely store their firearms unloaded and locked at home. Storing ≥ 1 firearm loaded and unlocked is more likely among veterans who reside in rural areas, separated from service before 2002, and report personal protection as the primary reason for ownership.33

Because evidence shows that delaying access to firearms—especially by transferring them out of the home—saves lives, many US health organizations have advocated for strategies that promote evaluation of firearm access and counseling safe storage for individuals at risk for suicide. These organizations include the US Office of the Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Public Health Association.34-36

Some health care systems—notably Kaiser Permanente and Henry Ford Health Systems—implemented protocols for lethal means assessment and counseling for behavioral health patients.37,38 Washington state requires specific health professionals to enroll in suicide prevention training that includes content on the risk of imminent harm by lethal means.39 California is designing a curriculum on counseling patients to reduce firearm injury for physicians and other health care practitioners (HCPs).40

The scope of these efforts, however, pale in comparison with the VA’s comprehensive, innovative lethal means safety approach. Since 2012, VA’s Suicide Prevention Program has distributed free firearm cable locks to veterans who request them. The VA has created lethal means public service announcements, social media messages, and websites.41-44 The VA distributes firearm and medication safe storage practice resource kits to its primary care, mental health and women’s health clinics, and Vet Centers, that include brochures, large poster cards, stickers, exam room posters, and provider pocket cards. VA developed an online lethal means safety counseling training that 20,000 VA HCPs have taken, and is moving toward a revamped mandatory training for VA’s mental health, pain, primary care, and emergency department (ED) providers and Veterans Crisis Line responders. VA offers free, individualized lethal means risk management consultation to all clinicians who work with veterans.45 VA includes lethal means safety procedures in its National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide,VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline,and VA Suicide Risk Evaluation and Suicide Prevention Safety Planrequired of clinicians.46-48

The VA also added public health strategies that promote safe storage practices for veterans through a partnership with the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF; the firearm industry trade association) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP).49 Collectively, these organizations cobranded an educational, training, and resource toolkit to foster community coalitions and gun retailer projects that encourage veterans to securely store firearms.50 The VA partnered with NSSF to post billboards in 8 states, encouraging storing firearms responsibly to prevent suicide. VA invited states and cities in the Governor/Mayoral Challenge to Prevent Suicide (joint VA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration endeavors) to develop plans for messaging regarding enhanced lethal means safety processes. The VA collaborated with local firearm advocates in community prevention pilot projects and in a “Together with Veterans” dissemination of material and outreach to rural veterans.51 Along with AFSP, VA hosted conferences for HCPs, policy makers, and stakeholders about innovations related to lethal means safety.52 In May 2020, the VA cosponsored a COVID-19 suicide prevention video with the United States Concealed Carry Association, NSSF, and AFSP, including ways that the firearm industry, gun owners, and their families can help.53

These programs are promising, and the Roadmap’s emphatic endorsement of lethal means safety approaches will accelerate advances. However, the Roadmap’s omissions are consequential. By focusing on population interventions, the document is silent about VA-specific or veteran-specific firearm access strategies. The means safety work of VA’s Suicide Prevention Program Office is scarcely recognized. Further, it stops short of specific legislative initiatives, making aspirational recommendations instead.

This paper will list proposed policy actions to bolster the acceptability and practice of lethal means safety with veterans. They cover an entire range of possibilities, from putting more teeth into the Roadmap’s population-wide interventions to initiatives tailored to veterans. Responsibility for leading and funding the changes would reside in a mix of Congress and state legislatures, the VA, and health system accreditation bodies. Although there is solid evidence that lethal means safety prevents suicide, it is unknown how these approaches affect firearm storage behaviors or suicide rates;therefore, the policy actions should come with federal and state funds for rigorous evaluation.54

Recommended Actions to Further Promote Safe Storage

Develop Campaigns to Shift Cultural Norms for Firearm Storage During Crises

National campaigns have been shown to be highly effective in changing injurious behaviors. Alliances and resources with regard to lethal means safety could be assembled, including federal funds for a campaign to shift social norms for firearm storage conversations and behaviors during crises. This campaign should be modeled after the “friends don’t let friends drive drunk” and “designated driver” campaigns that empower family and friends to protect one another. Since those campaigns’ inception in 1982, two-thirds of Americans have tried to prevent someone from driving after drinking,and traffic deaths involving alcohol-impaired crashes have decreased 65%.55,56

The comparable lethal means safety enterprise would encourage friends and family to talk with those in crisis about storing firearms safely. The campaign must use spokespersons who have strong respect and credibility among firearm owners, such as the NSSF and the United States Concealed Carry Association who have developed firearm suicide prevention websites and videos.57,58

The emphasis is that it’s a personal strength—not a failing—to talk to friends, loved ones, or counselors about storing guns until a crisis passes. Some of the current phrasing includes: “Hey, let me hold your guns for a while,” “People who love guns, love you,” and “Have a brave conversation.” 59-61

The national campaign should attempt to correct the inaccurate beliefs that suicide death always is the result of mental illness and is inevitable once seriously contemplated. In fact, more than half of the individuals who die by suicide have no diagnosed mental health condition.62 Other crises, such as with finances, relationships, or physical health, might be more contributory. These myths about suicide and mental illness weaken public and policy maker interest in solutions aimed toward accessing lethal means.

Facilitate Temporary Storage Out of the Home

The PREVENTS Roadmap Supplemental Materials concluded, “Moving firearms out of the home is generally cited as the safest, most desirable option; this can include storage with another person or at a location like a firearm range, armory, pawn shop, self-storage unit, or law enforcement agency, although state laws for firearm transfers may affect what options are legal.”63 This goal could be achieved by establishing grants to gun shops and ranges to offer free lockers for voluntary safe harbor.

The creation of free community lockers was a top PREVENTS recommendation. Likewise, the congressionally chartered COVER (Creating Options for Veterans' Expedited Recovery) Commission recommended grants “to further support the development of voluntary firearm safe storage options across the country.”64 Federal and state grants might resolve hesitations cited by retailers by covering all expenses for lockers, labor, and insurance for theft/damage/liability.65,66 Locker use would be free to the user, eliminating all financial barriers, although it is unknown whether monetary incentives change storage behaviors. Many firearm owners report that private gun shops or ranges are more acceptable than police stations for storage. If retailers come on board, changes in cultural storage norms might be expedited. An additional benefit could be reduction of accidental firearm fatalities in the home. States that have legal impediments to returning firearms to their owners could modify laws to achieve popular acceptance.

Congress could consider funding a national, easily accessible, public online directory of locations for out-of-home firearm storage, with staff to update the site. Colorado, Maryland, and Washington have developed online maps showing locations of firearm outlets and law enforcement agencies willing to consider temporary storage.67 A site directory for every state would simplify the process for individuals and family members seeking to temporarily and voluntarily store guns offsite during a crisis. Online directories have been backed by firearm groups,although their effect on storage behavior is not known.68State governments should strive to make it easier to quickly transfer firearms temporarily to trusted individuals in situations of imminent suicide risk. Rapid transfer of firearms to friends or family could effectively separate lethal means from individuals during a crisis. However, some state laws that require background checks whenever a gun is transferred might delay such transfers.69 Only a few states have legal exemptions that could expedite temporary transfers when it’s potentially lifesaving.

Improve In-Home Safe Storage Options

Out-of-home transfer of firearms might not be acceptable or feasible for some veterans. Accordingly, there is need for improved options for safer in-home storage, especially because of frequent unsafe storage practices among veterans. The VA could consider sponsoring another open-innovation Gun Safety Matters Challenge like the one it held in 2018 for in-home firearm storage technology that could prevent suicide.70 Further innovation and bringing winning entries to market has great potential.

Require Enhanced Lethal Means Safety Standards and Training

Broader lethal means safety competence is needed, both in the VA where modest levels of training has been implemented and in the community among Veterans Community Care Program (VCCP) HCPs where it hasn’t. Oversight for enhanced standards and training—as well as of all lethal means initiatives and their program evaluations—might best be accomplished by establishing a separate VA Suicide Prevention Program lethal means safety team. Veteran firearm suicide is a significant problem that warrants its own discrete, permanent VA team (although joining with the US Department of Defense might be advantageous). The VA Suicide Prevention Program has been the industry leader and innovator in this field and should be conferred continued stewardship going forward.

The VA is moving toward requiring lethal means safety counseling training for mental health, pain, primary care, women’s health, ED providers, and Veterans Crisis Line responders.

VCCP HCPs, however, have no required training in lethal means safety counseling or even in basic suicide risk identification and intervention, and the Roadmap did not stipulate that this deficiency should be remedied. Surveys have revealed that community HCPs rarely screen or counsel their patients—even those at high risk—about firearm safety.71 A bill was introduced in Congress August 21, 2020, to expand VA suicide prevention training with firearms community input on cultural competency components and mandate that VA and VCCP providers, and some others with frequent contact with veterans, receive this training.72

Training should be obligatory for VA and VCCP HCPs and trainees most likely to interface with at-risk veterans, including those working in mental health, primary care, pain, women’s health, and ED. Training also should include geriatrics, extended care, and oncology providers because most older adults who die by firearm suicide have physical health problems but no known mental illness.73-75 Lethal means safety counseling training has been shown to improve HCPs’ knowledge about the relationship between access to lethal means and suicide, and confidence in and frequency of having lethal means safety counseling conversations.76 Likewise, training should include peer counselors; veterans are receptive to fellow veterans raising the topic of safe storage.56,77 If feasible, the training should include time to rehearse skills shown to motivate behavior change among patients.

The VA should aim to improve semiyearly clinical pertinence reviews and safety plans for VA and VCCP mental health providers. VA could conduct clinical pertinence reviews that ascertain whether a suicide assessment is recorded in the health record, and when a patient is at elevated risk, whether a lethal means safety assessment and plan is documented.

VA’s safety plan template, although best practice, covers only the initial steps to take when suicide potential is identified. A standard for follow-up is needed. If an at-risk patient agrees to take a safe storage action, subsequent contact HCPs need to ask and document what action was performed. This action will help ensure that at-risk patients with ready access do not fall through the cracks. This suggestion lends itself to studying changes in veterans’ storage habits after intervention.

I also recommend that health care accrediting bodies include lethal means safety assessment, counseling, and follow up as a suicide prevention standard. This recommendation applies to more than just the VA health care system and recognizes that modifying accrediting body standards is an expeditious way to drive change in health care. The accreditation standards of the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities for behavioral health and opioid treatment programs, and of the Joint Commission for medical centers do not require lethal means safety assessment and intervention.78,79

Conclusions

Suicide prevention requires a multimodal approach, and attention to firearms access must become a more salient component. The high rate of veteran suicides involving firearms requires far-reaching interventions at societal, institutional, community, family, and individual levels. With the link between ready access to firearms and suicide supported by research and now firmly recognized by the PREVENTS Roadmap, we have a fresh opportunity to reduce suicide among veterans. Efforts must move vigorously forward until it is commonplace for veterans—and anyone—at risk of suicide to voluntarily reduce immediate access to firearms.

US veterans die by suicide at a higher rate than that of the civilian population, and are more likely to use a firearm as their lethal means.1 In 2017, 6,139 veterans died by suicide, about 17 per day.1 Nearly as many veterans die by suicide yearly as the total aggregate number of service members killed in action during the decades-long Iraq and Afghanistan operations.2 Veterans are more likely to own firearms than are civilians.3 Until June 2020, however, systemic efforts to address the use of firearms in suicide had been largely evaded, entangled in gun advocates’ assertion that veterans’ constitutional right to bear arms would be infringed.

That impasse changed with the President’s Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End the National Tragedy of Suicide (PREVENTS) task force report, released June 17, 2020.4 Although the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has pioneered initiatives to encourage safe firearm storage for at-risk veterans, and major public health organizations have endorsed the utility of lethal means safety strategies, the policy language of the Roadmap released by the White House is unprecedented. Lethal means safety refers to efforts aimed at increasing the time and distance needed to access suicide methods.

Among the report’s 10 recommendations, the Roadmap verified the link between, and the need to address, at-risk veterans and their access to firearms (the author was a minor consultant to a PREVENTS workgroup). The document states, “The science supporting lethal means safety is robust and compelling: enhancing safety measures specific to the availability and accessibility of potential lethal means saves lives. A key component of effective suicide prevention is voluntary reduction in the ability to access lethal means with respect to time, distance, and convenience, particularly during acute suicidal crises.”4 The report recommends widespread distribution of safety education materials that encourage at-risk individuals to temporarily transfer or store their guns safely, and the expansion of free or affordable options for storing weapons, among other recommendations.

This paper reviews the literature on the intersection of veterans, firearms, and suicide, then explores existing VA prevention initiatives aimed at reducing at-risk veterans’ access to lethal means and offers policy recommendations to expand efforts in the context of the PREVENTS Roadmap.

Veteran Suicide and Firearms

Firearms are, by far, the most common lethal means used by veterans who die by suicide. About 71% of male veteran suicide deaths and 43% of female veteran suicide deaths are with firearms, rates that far exceed those of nonveterans (Table).For all age groups, veterans are more likely to complete suicide by firearm than are nonveterans.5

Veteran suicide and gun ownership rates are highest in rural areas.6,7 When compared with veterans living in urban areas, veterans in rural areas are 20% more likely to die by suicide, with the excessive risk largely attributed to suicide by firearm.8

Access to firearms at home increases the risk of suicide. Individuals with any firearm at home are 3 times more likely to die by suicide than is a person with no firearms at home. The elevated suicide risk applies to other household members as well as the firearm owner.9-18 Survivors of suicide attempts using firearms report that the availability of guns at home is the primary reason for their method choice.19,20

There is a common misperception that people who are intent on suicide and are thwarted or survive an attempt using one method will try again with another.21 Suicidal crises often represent a conflicting wish to live or die,22 and approximately two-thirds of those who survive an attempt will never try again. About 23% reattempt nonfatally, and only 10% die by suicide.23-25 However, people who attempt suicide with a firearm usually won’t get a chance at a new start, because 90% of such acts are fatal.26

Although some suicide attempts might be contemplated or planned over an extended period, the decision is impulsive for most individuals. Surveys have found that many people who survive suicide attempts began the act only minutes or hours after making the decision to end their life.27-30 The high-risk, acute phase of many suicidal crises arise quickly and is fleeting.

Limiting the ease by which at-risk individuals can access firearms has been shown to prevent suicide. In 2006, the overall suicide rate in Israel dropped 40% when the Israeli Defense Forces began requiring soldiers to store their firearms on base before going on weekend leave.Since then, the suicide rate has declined even further.31,32

Delaying Access to Firearms for At-Risk Veterans

Among veterans, 45% own ≥ 1 firearms (47% male and 24% female veterans vs 30% male and 12% female nonveterans).3 Many veteran firearm owners (34% male and 13% female) store ≥ 1 gun loaded and unlocked; 44% store a firearm either loaded or unlocked. Only 23% safely store their firearms unloaded and locked at home. Storing ≥ 1 firearm loaded and unlocked is more likely among veterans who reside in rural areas, separated from service before 2002, and report personal protection as the primary reason for ownership.33

Because evidence shows that delaying access to firearms—especially by transferring them out of the home—saves lives, many US health organizations have advocated for strategies that promote evaluation of firearm access and counseling safe storage for individuals at risk for suicide. These organizations include the US Office of the Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Public Health Association.34-36

Some health care systems—notably Kaiser Permanente and Henry Ford Health Systems—implemented protocols for lethal means assessment and counseling for behavioral health patients.37,38 Washington state requires specific health professionals to enroll in suicide prevention training that includes content on the risk of imminent harm by lethal means.39 California is designing a curriculum on counseling patients to reduce firearm injury for physicians and other health care practitioners (HCPs).40

The scope of these efforts, however, pale in comparison with the VA’s comprehensive, innovative lethal means safety approach. Since 2012, VA’s Suicide Prevention Program has distributed free firearm cable locks to veterans who request them. The VA has created lethal means public service announcements, social media messages, and websites.41-44 The VA distributes firearm and medication safe storage practice resource kits to its primary care, mental health and women’s health clinics, and Vet Centers, that include brochures, large poster cards, stickers, exam room posters, and provider pocket cards. VA developed an online lethal means safety counseling training that 20,000 VA HCPs have taken, and is moving toward a revamped mandatory training for VA’s mental health, pain, primary care, and emergency department (ED) providers and Veterans Crisis Line responders. VA offers free, individualized lethal means risk management consultation to all clinicians who work with veterans.45 VA includes lethal means safety procedures in its National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide,VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline,and VA Suicide Risk Evaluation and Suicide Prevention Safety Planrequired of clinicians.46-48

The VA also added public health strategies that promote safe storage practices for veterans through a partnership with the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF; the firearm industry trade association) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP).49 Collectively, these organizations cobranded an educational, training, and resource toolkit to foster community coalitions and gun retailer projects that encourage veterans to securely store firearms.50 The VA partnered with NSSF to post billboards in 8 states, encouraging storing firearms responsibly to prevent suicide. VA invited states and cities in the Governor/Mayoral Challenge to Prevent Suicide (joint VA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration endeavors) to develop plans for messaging regarding enhanced lethal means safety processes. The VA collaborated with local firearm advocates in community prevention pilot projects and in a “Together with Veterans” dissemination of material and outreach to rural veterans.51 Along with AFSP, VA hosted conferences for HCPs, policy makers, and stakeholders about innovations related to lethal means safety.52 In May 2020, the VA cosponsored a COVID-19 suicide prevention video with the United States Concealed Carry Association, NSSF, and AFSP, including ways that the firearm industry, gun owners, and their families can help.53

These programs are promising, and the Roadmap’s emphatic endorsement of lethal means safety approaches will accelerate advances. However, the Roadmap’s omissions are consequential. By focusing on population interventions, the document is silent about VA-specific or veteran-specific firearm access strategies. The means safety work of VA’s Suicide Prevention Program Office is scarcely recognized. Further, it stops short of specific legislative initiatives, making aspirational recommendations instead.

This paper will list proposed policy actions to bolster the acceptability and practice of lethal means safety with veterans. They cover an entire range of possibilities, from putting more teeth into the Roadmap’s population-wide interventions to initiatives tailored to veterans. Responsibility for leading and funding the changes would reside in a mix of Congress and state legislatures, the VA, and health system accreditation bodies. Although there is solid evidence that lethal means safety prevents suicide, it is unknown how these approaches affect firearm storage behaviors or suicide rates;therefore, the policy actions should come with federal and state funds for rigorous evaluation.54

Recommended Actions to Further Promote Safe Storage

Develop Campaigns to Shift Cultural Norms for Firearm Storage During Crises

National campaigns have been shown to be highly effective in changing injurious behaviors. Alliances and resources with regard to lethal means safety could be assembled, including federal funds for a campaign to shift social norms for firearm storage conversations and behaviors during crises. This campaign should be modeled after the “friends don’t let friends drive drunk” and “designated driver” campaigns that empower family and friends to protect one another. Since those campaigns’ inception in 1982, two-thirds of Americans have tried to prevent someone from driving after drinking,and traffic deaths involving alcohol-impaired crashes have decreased 65%.55,56

The comparable lethal means safety enterprise would encourage friends and family to talk with those in crisis about storing firearms safely. The campaign must use spokespersons who have strong respect and credibility among firearm owners, such as the NSSF and the United States Concealed Carry Association who have developed firearm suicide prevention websites and videos.57,58

The emphasis is that it’s a personal strength—not a failing—to talk to friends, loved ones, or counselors about storing guns until a crisis passes. Some of the current phrasing includes: “Hey, let me hold your guns for a while,” “People who love guns, love you,” and “Have a brave conversation.” 59-61

The national campaign should attempt to correct the inaccurate beliefs that suicide death always is the result of mental illness and is inevitable once seriously contemplated. In fact, more than half of the individuals who die by suicide have no diagnosed mental health condition.62 Other crises, such as with finances, relationships, or physical health, might be more contributory. These myths about suicide and mental illness weaken public and policy maker interest in solutions aimed toward accessing lethal means.

Facilitate Temporary Storage Out of the Home

The PREVENTS Roadmap Supplemental Materials concluded, “Moving firearms out of the home is generally cited as the safest, most desirable option; this can include storage with another person or at a location like a firearm range, armory, pawn shop, self-storage unit, or law enforcement agency, although state laws for firearm transfers may affect what options are legal.”63 This goal could be achieved by establishing grants to gun shops and ranges to offer free lockers for voluntary safe harbor.

The creation of free community lockers was a top PREVENTS recommendation. Likewise, the congressionally chartered COVER (Creating Options for Veterans' Expedited Recovery) Commission recommended grants “to further support the development of voluntary firearm safe storage options across the country.”64 Federal and state grants might resolve hesitations cited by retailers by covering all expenses for lockers, labor, and insurance for theft/damage/liability.65,66 Locker use would be free to the user, eliminating all financial barriers, although it is unknown whether monetary incentives change storage behaviors. Many firearm owners report that private gun shops or ranges are more acceptable than police stations for storage. If retailers come on board, changes in cultural storage norms might be expedited. An additional benefit could be reduction of accidental firearm fatalities in the home. States that have legal impediments to returning firearms to their owners could modify laws to achieve popular acceptance.

Congress could consider funding a national, easily accessible, public online directory of locations for out-of-home firearm storage, with staff to update the site. Colorado, Maryland, and Washington have developed online maps showing locations of firearm outlets and law enforcement agencies willing to consider temporary storage.67 A site directory for every state would simplify the process for individuals and family members seeking to temporarily and voluntarily store guns offsite during a crisis. Online directories have been backed by firearm groups,although their effect on storage behavior is not known.68State governments should strive to make it easier to quickly transfer firearms temporarily to trusted individuals in situations of imminent suicide risk. Rapid transfer of firearms to friends or family could effectively separate lethal means from individuals during a crisis. However, some state laws that require background checks whenever a gun is transferred might delay such transfers.69 Only a few states have legal exemptions that could expedite temporary transfers when it’s potentially lifesaving.

Improve In-Home Safe Storage Options

Out-of-home transfer of firearms might not be acceptable or feasible for some veterans. Accordingly, there is need for improved options for safer in-home storage, especially because of frequent unsafe storage practices among veterans. The VA could consider sponsoring another open-innovation Gun Safety Matters Challenge like the one it held in 2018 for in-home firearm storage technology that could prevent suicide.70 Further innovation and bringing winning entries to market has great potential.

Require Enhanced Lethal Means Safety Standards and Training

Broader lethal means safety competence is needed, both in the VA where modest levels of training has been implemented and in the community among Veterans Community Care Program (VCCP) HCPs where it hasn’t. Oversight for enhanced standards and training—as well as of all lethal means initiatives and their program evaluations—might best be accomplished by establishing a separate VA Suicide Prevention Program lethal means safety team. Veteran firearm suicide is a significant problem that warrants its own discrete, permanent VA team (although joining with the US Department of Defense might be advantageous). The VA Suicide Prevention Program has been the industry leader and innovator in this field and should be conferred continued stewardship going forward.

The VA is moving toward requiring lethal means safety counseling training for mental health, pain, primary care, women’s health, ED providers, and Veterans Crisis Line responders.

VCCP HCPs, however, have no required training in lethal means safety counseling or even in basic suicide risk identification and intervention, and the Roadmap did not stipulate that this deficiency should be remedied. Surveys have revealed that community HCPs rarely screen or counsel their patients—even those at high risk—about firearm safety.71 A bill was introduced in Congress August 21, 2020, to expand VA suicide prevention training with firearms community input on cultural competency components and mandate that VA and VCCP providers, and some others with frequent contact with veterans, receive this training.72

Training should be obligatory for VA and VCCP HCPs and trainees most likely to interface with at-risk veterans, including those working in mental health, primary care, pain, women’s health, and ED. Training also should include geriatrics, extended care, and oncology providers because most older adults who die by firearm suicide have physical health problems but no known mental illness.73-75 Lethal means safety counseling training has been shown to improve HCPs’ knowledge about the relationship between access to lethal means and suicide, and confidence in and frequency of having lethal means safety counseling conversations.76 Likewise, training should include peer counselors; veterans are receptive to fellow veterans raising the topic of safe storage.56,77 If feasible, the training should include time to rehearse skills shown to motivate behavior change among patients.

The VA should aim to improve semiyearly clinical pertinence reviews and safety plans for VA and VCCP mental health providers. VA could conduct clinical pertinence reviews that ascertain whether a suicide assessment is recorded in the health record, and when a patient is at elevated risk, whether a lethal means safety assessment and plan is documented.

VA’s safety plan template, although best practice, covers only the initial steps to take when suicide potential is identified. A standard for follow-up is needed. If an at-risk patient agrees to take a safe storage action, subsequent contact HCPs need to ask and document what action was performed. This action will help ensure that at-risk patients with ready access do not fall through the cracks. This suggestion lends itself to studying changes in veterans’ storage habits after intervention.

I also recommend that health care accrediting bodies include lethal means safety assessment, counseling, and follow up as a suicide prevention standard. This recommendation applies to more than just the VA health care system and recognizes that modifying accrediting body standards is an expeditious way to drive change in health care. The accreditation standards of the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities for behavioral health and opioid treatment programs, and of the Joint Commission for medical centers do not require lethal means safety assessment and intervention.78,79

Conclusions

Suicide prevention requires a multimodal approach, and attention to firearms access must become a more salient component. The high rate of veteran suicides involving firearms requires far-reaching interventions at societal, institutional, community, family, and individual levels. With the link between ready access to firearms and suicide supported by research and now firmly recognized by the PREVENTS Roadmap, we have a fresh opportunity to reduce suicide among veterans. Efforts must move vigorously forward until it is commonplace for veterans—and anyone—at risk of suicide to voluntarily reduce immediate access to firearms.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 2019. Accessed August 20, 2020.

2. US Department of Defense. Casualty status. https://www.defense.gov/casualty.pdf. Published August 17, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020.

3. Cleveland EC, Azreal D, Simonetti JA, Miller M. Firearm ownership among American veterans: findings from the 2015 National Firearm Survey. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4:33. doi:10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PREVENTS: the President’s roadmap to empower veterans and end a national tragedy of suicide. https://www.va.gov/PREVENTS/docs/PRE-007-The-PREVENTS-Roadmap-1-2_508.pdf. Published June 17, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020.

5. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N. Firearm suicide among veterans in the general population: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Trauma. 2009;67(3):503-507. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b36521

6. Miller M, Barber C, White RA, Azrael D. Firearms and suicide in the United States: is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):946-955. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt197

7. Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack, SP, Haileyesus, T, Kresnow-Sedacca M. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death—United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(18):1-16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1

8. McCarthy JF, Blow FC, Ignacio RV, Ilgen MA, Austin KL, Valenstein M. Suicide among patients in the Veterans Affairs Health System: rural-urban differences in rates, risks and methods. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S111-S117. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300463

9. RAND Corporation. The relationship between firearm availability and suicide. https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/essays/firearm-availability-suicide.html. Published March 2, 2018. Accessed August 20, 2020.