User login

Ms. H, age 42, is being treated by her family physician for her second episode of major depressive disorder (MDD). When she was 35, Ms. H experienced her first episode of MDD, which was successfully treated with

At the 8-week follow-up appointment, the physician notes how much better Ms. H seems to be doing. He says that because she has had such a good response, she should continue the fluoxetine and come back in 3 months. Later that evening, Ms. H reflects on her visit. Although she feels better, she still does not feel normal. In fact, she is not sure that she has really felt normal since before her first depressive episode. Ms. H decides to see a psychiatrist.

At her first appointment, the psychiatrist asks Ms. H to complete the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms–Self Rated (QIDS-SR) scale. Her QIDS-SR score is 6, which is consistent with mild residual symptoms of depression.1 The psychiatrist increases the fluoxetine dosage to 40 mg/d and recommends that she complete a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Although psychiatry currently does not have tests that provide continuous data such as blood pressure or HbA1c, well-validated rating scales can help clinicians in getting their patients to achieve symptom remission. Measurement-based care is the “systematic use of measurement tools to monitor progress and guide treatment choices.”1 Originally, psychometric rating scales were designed for research; typically, they were administered by the clinician, and were too long to be used in routine outpatient clinical practice. Subsequently, it was determined that patients without psychotic symptoms or cognitive deficits can accurately assess their own symptoms, and this led to the development of short self-assessment scales that have a high level of reliability when compared with longer, clinician-administered instruments. Despite the availability of several validated, brief rating scales, it is estimated that only approximately 18% of psychiatrists use them in clinical practice.2

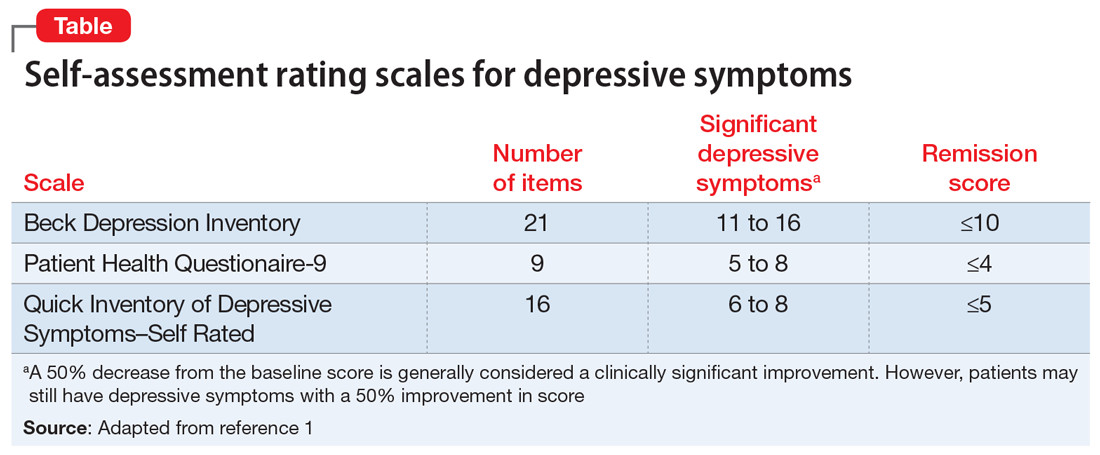

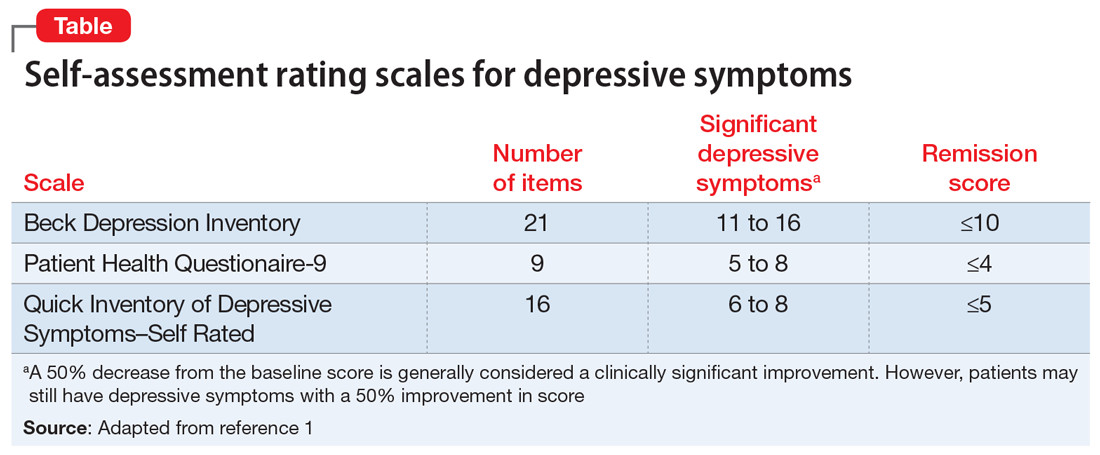

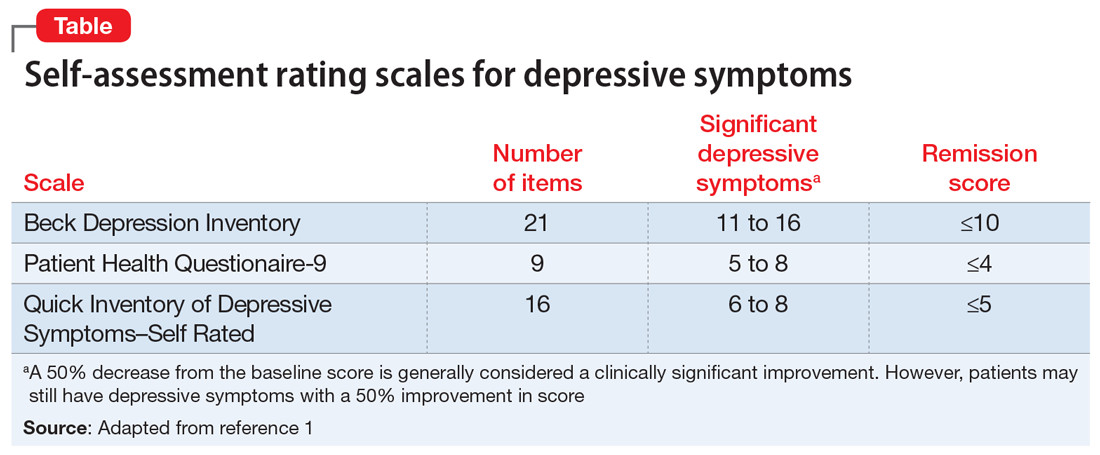

Self-rated scales for depression have been shown to be as valid as clinician-rated scales. For depression, the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9), based on the 9 symptom criteria associated with a diagnosis of MDD, is likely the most commonly used self-assessment scale.1 However, the QIDS-SR and the Beck Depression Inventory are both well-validated.1 In particular, QIDS-SR scores and score changes have been shown to be comparable with those on the QIDS-Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) scale.3 A 50% decrease in score typically is defined as a clinical response. Remission of symptoms is often defined as a score ≤4 on the PHQ-9 or ≤5 on the QIDS-SR (Table1). Similar to laboratory tests, rating scales are not diagnostic, but are a piece of information for the clinician to use in making diagnostic and treatment decisions.

The use of brief rating scales can help identify symptoms that may not come up in discussion with the patient, and it provides a systematic method of reviewing symptoms. Patients may be encouraged when they see a decrease in their scores after beginning treatment.2 Patients with depression need to complete rating scales frequently, just as a patient with hypertension would need their blood pressure frequently monitored.2 Frequent measurement with rating scales may help identify residual depressive symptoms that indicate the need for additional intervention. Residual depressive symptoms are the best predictor of the recurrence of depression, and treatment to remission is essential in preventing recurrence. In fact, recurrence is 2 to 3 times more likely in patients who do not achieve remission.1

Continue to: Optimizing the use of self-rating scales...

Optimizing the use of self-rating scales

To save time, patients can complete a rating scale before seeing the clinician, and the use of computerized applications can automatically sum scores and plot response graphs.4 Some researchers have suggested that some patients may be more honest in completing a self-assessment than in their verbal responses to the clinician.4 It is important to discuss the rating scale results with the patient.2 With a newly diagnosed patient, goals for treatment and the treatment plan can be outlined. During follow-up visits, clinicians should note areas of improvement and provide encouragement. If the patient’s symptoms are not improving appropriately, the clinician should discuss treatment options and offer the patient hope. This may improve the patient’s engagement in care and their understanding of how symptoms are associated with their illness.2 Studies have suggested that the use of validated rating tools (along with other interventions) can result in faster improvement in symptoms and higher response rates, and can assist in achieving remission.1,2,5

CASE CONTINUED

After 6 weeks of CBT and the increased fluoxetine dose, Ms. H returns to her psychiatrist for a follow-up visit. Her QIDS-SR score is 4, which is down from her initial score of 6. Ms. H is elated when she sees that her symptoms score has decreased since the previous visit. To confirm this finding, the psychiatrist completes the QIDS-C, and records a score of 3. The psychiatrist discusses the appropriate continuation of fluoxetine and CBT.

In this case, the use of a brief clinical rating scale helped Ms. H’s psychiatrist identify residual depressive symptoms and modify treatment so that she achieved remission. Using patient-reported outcomes also helps facilitate meaningful conversations between the patient and clinician and helps identify symptoms suggestive of relapse.2 Although this case focused on the use of measurement-based care in depression, brief symptom rating scales for most major psychiatric disorders—many of them self-assessments—also are available, as are brief rating scales to assess medication adverse effects and adherence.5

Just as clinicians in other areas of medicine use assessments such as laboratory tests and blood pressure monitoring for initial assessment and in following response to treatment, measurement-based care allows for a quasi-objective evaluation of patients with psychiatric disorders. Improved response rates, time to response, and patient engagement are all positive results of measurement-based care

Related Resources

- Martin-Cook K, Palmer L, Thornton L, et al. Setting measurement-based care in motion: practical lessons in the implementation and integration of measurement-based care in psychiatry clinical practice. Neuropsychiatric Disease & Treatment. 2021;17:1621-1631.

- Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurementbased care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Self-rated scales are believed to be as reliable as clinician-rated scales in assessing symptoms in patients who are not cognitively impaired.

- The use of rating scales can enhance engagement of the patient with the clinician.

- Utilizing computer- or smartphone appbased rating scales allows for automatic scoring and graphing.

- The use of rating scales in the pharmacotherapy of depression has been associated with more rapid symptoms improvement, greater response rates, and a greater likelihood of achieving remission.

- Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31. doi:10.4088/ JCP.8133su1c.04

- Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):324-335.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):73-82.

- Trivedi MH, Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, et al. Implementing measurement-based care to determine and treat inadequate response. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(3):OT19037BR1. doi: 10.4088/JCP.OT19037BR1

- Morris DW, Trivedi MH. Measurement-based care for unipolar depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(6):446-458.

Ms. H, age 42, is being treated by her family physician for her second episode of major depressive disorder (MDD). When she was 35, Ms. H experienced her first episode of MDD, which was successfully treated with

At the 8-week follow-up appointment, the physician notes how much better Ms. H seems to be doing. He says that because she has had such a good response, she should continue the fluoxetine and come back in 3 months. Later that evening, Ms. H reflects on her visit. Although she feels better, she still does not feel normal. In fact, she is not sure that she has really felt normal since before her first depressive episode. Ms. H decides to see a psychiatrist.

At her first appointment, the psychiatrist asks Ms. H to complete the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms–Self Rated (QIDS-SR) scale. Her QIDS-SR score is 6, which is consistent with mild residual symptoms of depression.1 The psychiatrist increases the fluoxetine dosage to 40 mg/d and recommends that she complete a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Although psychiatry currently does not have tests that provide continuous data such as blood pressure or HbA1c, well-validated rating scales can help clinicians in getting their patients to achieve symptom remission. Measurement-based care is the “systematic use of measurement tools to monitor progress and guide treatment choices.”1 Originally, psychometric rating scales were designed for research; typically, they were administered by the clinician, and were too long to be used in routine outpatient clinical practice. Subsequently, it was determined that patients without psychotic symptoms or cognitive deficits can accurately assess their own symptoms, and this led to the development of short self-assessment scales that have a high level of reliability when compared with longer, clinician-administered instruments. Despite the availability of several validated, brief rating scales, it is estimated that only approximately 18% of psychiatrists use them in clinical practice.2

Self-rated scales for depression have been shown to be as valid as clinician-rated scales. For depression, the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9), based on the 9 symptom criteria associated with a diagnosis of MDD, is likely the most commonly used self-assessment scale.1 However, the QIDS-SR and the Beck Depression Inventory are both well-validated.1 In particular, QIDS-SR scores and score changes have been shown to be comparable with those on the QIDS-Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) scale.3 A 50% decrease in score typically is defined as a clinical response. Remission of symptoms is often defined as a score ≤4 on the PHQ-9 or ≤5 on the QIDS-SR (Table1). Similar to laboratory tests, rating scales are not diagnostic, but are a piece of information for the clinician to use in making diagnostic and treatment decisions.

The use of brief rating scales can help identify symptoms that may not come up in discussion with the patient, and it provides a systematic method of reviewing symptoms. Patients may be encouraged when they see a decrease in their scores after beginning treatment.2 Patients with depression need to complete rating scales frequently, just as a patient with hypertension would need their blood pressure frequently monitored.2 Frequent measurement with rating scales may help identify residual depressive symptoms that indicate the need for additional intervention. Residual depressive symptoms are the best predictor of the recurrence of depression, and treatment to remission is essential in preventing recurrence. In fact, recurrence is 2 to 3 times more likely in patients who do not achieve remission.1

Continue to: Optimizing the use of self-rating scales...

Optimizing the use of self-rating scales

To save time, patients can complete a rating scale before seeing the clinician, and the use of computerized applications can automatically sum scores and plot response graphs.4 Some researchers have suggested that some patients may be more honest in completing a self-assessment than in their verbal responses to the clinician.4 It is important to discuss the rating scale results with the patient.2 With a newly diagnosed patient, goals for treatment and the treatment plan can be outlined. During follow-up visits, clinicians should note areas of improvement and provide encouragement. If the patient’s symptoms are not improving appropriately, the clinician should discuss treatment options and offer the patient hope. This may improve the patient’s engagement in care and their understanding of how symptoms are associated with their illness.2 Studies have suggested that the use of validated rating tools (along with other interventions) can result in faster improvement in symptoms and higher response rates, and can assist in achieving remission.1,2,5

CASE CONTINUED

After 6 weeks of CBT and the increased fluoxetine dose, Ms. H returns to her psychiatrist for a follow-up visit. Her QIDS-SR score is 4, which is down from her initial score of 6. Ms. H is elated when she sees that her symptoms score has decreased since the previous visit. To confirm this finding, the psychiatrist completes the QIDS-C, and records a score of 3. The psychiatrist discusses the appropriate continuation of fluoxetine and CBT.

In this case, the use of a brief clinical rating scale helped Ms. H’s psychiatrist identify residual depressive symptoms and modify treatment so that she achieved remission. Using patient-reported outcomes also helps facilitate meaningful conversations between the patient and clinician and helps identify symptoms suggestive of relapse.2 Although this case focused on the use of measurement-based care in depression, brief symptom rating scales for most major psychiatric disorders—many of them self-assessments—also are available, as are brief rating scales to assess medication adverse effects and adherence.5

Just as clinicians in other areas of medicine use assessments such as laboratory tests and blood pressure monitoring for initial assessment and in following response to treatment, measurement-based care allows for a quasi-objective evaluation of patients with psychiatric disorders. Improved response rates, time to response, and patient engagement are all positive results of measurement-based care

Related Resources

- Martin-Cook K, Palmer L, Thornton L, et al. Setting measurement-based care in motion: practical lessons in the implementation and integration of measurement-based care in psychiatry clinical practice. Neuropsychiatric Disease & Treatment. 2021;17:1621-1631.

- Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurementbased care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Self-rated scales are believed to be as reliable as clinician-rated scales in assessing symptoms in patients who are not cognitively impaired.

- The use of rating scales can enhance engagement of the patient with the clinician.

- Utilizing computer- or smartphone appbased rating scales allows for automatic scoring and graphing.

- The use of rating scales in the pharmacotherapy of depression has been associated with more rapid symptoms improvement, greater response rates, and a greater likelihood of achieving remission.

Ms. H, age 42, is being treated by her family physician for her second episode of major depressive disorder (MDD). When she was 35, Ms. H experienced her first episode of MDD, which was successfully treated with

At the 8-week follow-up appointment, the physician notes how much better Ms. H seems to be doing. He says that because she has had such a good response, she should continue the fluoxetine and come back in 3 months. Later that evening, Ms. H reflects on her visit. Although she feels better, she still does not feel normal. In fact, she is not sure that she has really felt normal since before her first depressive episode. Ms. H decides to see a psychiatrist.

At her first appointment, the psychiatrist asks Ms. H to complete the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms–Self Rated (QIDS-SR) scale. Her QIDS-SR score is 6, which is consistent with mild residual symptoms of depression.1 The psychiatrist increases the fluoxetine dosage to 40 mg/d and recommends that she complete a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Although psychiatry currently does not have tests that provide continuous data such as blood pressure or HbA1c, well-validated rating scales can help clinicians in getting their patients to achieve symptom remission. Measurement-based care is the “systematic use of measurement tools to monitor progress and guide treatment choices.”1 Originally, psychometric rating scales were designed for research; typically, they were administered by the clinician, and were too long to be used in routine outpatient clinical practice. Subsequently, it was determined that patients without psychotic symptoms or cognitive deficits can accurately assess their own symptoms, and this led to the development of short self-assessment scales that have a high level of reliability when compared with longer, clinician-administered instruments. Despite the availability of several validated, brief rating scales, it is estimated that only approximately 18% of psychiatrists use them in clinical practice.2

Self-rated scales for depression have been shown to be as valid as clinician-rated scales. For depression, the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9), based on the 9 symptom criteria associated with a diagnosis of MDD, is likely the most commonly used self-assessment scale.1 However, the QIDS-SR and the Beck Depression Inventory are both well-validated.1 In particular, QIDS-SR scores and score changes have been shown to be comparable with those on the QIDS-Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) scale.3 A 50% decrease in score typically is defined as a clinical response. Remission of symptoms is often defined as a score ≤4 on the PHQ-9 or ≤5 on the QIDS-SR (Table1). Similar to laboratory tests, rating scales are not diagnostic, but are a piece of information for the clinician to use in making diagnostic and treatment decisions.

The use of brief rating scales can help identify symptoms that may not come up in discussion with the patient, and it provides a systematic method of reviewing symptoms. Patients may be encouraged when they see a decrease in their scores after beginning treatment.2 Patients with depression need to complete rating scales frequently, just as a patient with hypertension would need their blood pressure frequently monitored.2 Frequent measurement with rating scales may help identify residual depressive symptoms that indicate the need for additional intervention. Residual depressive symptoms are the best predictor of the recurrence of depression, and treatment to remission is essential in preventing recurrence. In fact, recurrence is 2 to 3 times more likely in patients who do not achieve remission.1

Continue to: Optimizing the use of self-rating scales...

Optimizing the use of self-rating scales

To save time, patients can complete a rating scale before seeing the clinician, and the use of computerized applications can automatically sum scores and plot response graphs.4 Some researchers have suggested that some patients may be more honest in completing a self-assessment than in their verbal responses to the clinician.4 It is important to discuss the rating scale results with the patient.2 With a newly diagnosed patient, goals for treatment and the treatment plan can be outlined. During follow-up visits, clinicians should note areas of improvement and provide encouragement. If the patient’s symptoms are not improving appropriately, the clinician should discuss treatment options and offer the patient hope. This may improve the patient’s engagement in care and their understanding of how symptoms are associated with their illness.2 Studies have suggested that the use of validated rating tools (along with other interventions) can result in faster improvement in symptoms and higher response rates, and can assist in achieving remission.1,2,5

CASE CONTINUED

After 6 weeks of CBT and the increased fluoxetine dose, Ms. H returns to her psychiatrist for a follow-up visit. Her QIDS-SR score is 4, which is down from her initial score of 6. Ms. H is elated when she sees that her symptoms score has decreased since the previous visit. To confirm this finding, the psychiatrist completes the QIDS-C, and records a score of 3. The psychiatrist discusses the appropriate continuation of fluoxetine and CBT.

In this case, the use of a brief clinical rating scale helped Ms. H’s psychiatrist identify residual depressive symptoms and modify treatment so that she achieved remission. Using patient-reported outcomes also helps facilitate meaningful conversations between the patient and clinician and helps identify symptoms suggestive of relapse.2 Although this case focused on the use of measurement-based care in depression, brief symptom rating scales for most major psychiatric disorders—many of them self-assessments—also are available, as are brief rating scales to assess medication adverse effects and adherence.5

Just as clinicians in other areas of medicine use assessments such as laboratory tests and blood pressure monitoring for initial assessment and in following response to treatment, measurement-based care allows for a quasi-objective evaluation of patients with psychiatric disorders. Improved response rates, time to response, and patient engagement are all positive results of measurement-based care

Related Resources

- Martin-Cook K, Palmer L, Thornton L, et al. Setting measurement-based care in motion: practical lessons in the implementation and integration of measurement-based care in psychiatry clinical practice. Neuropsychiatric Disease & Treatment. 2021;17:1621-1631.

- Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurementbased care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Self-rated scales are believed to be as reliable as clinician-rated scales in assessing symptoms in patients who are not cognitively impaired.

- The use of rating scales can enhance engagement of the patient with the clinician.

- Utilizing computer- or smartphone appbased rating scales allows for automatic scoring and graphing.

- The use of rating scales in the pharmacotherapy of depression has been associated with more rapid symptoms improvement, greater response rates, and a greater likelihood of achieving remission.

- Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31. doi:10.4088/ JCP.8133su1c.04

- Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):324-335.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):73-82.

- Trivedi MH, Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, et al. Implementing measurement-based care to determine and treat inadequate response. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(3):OT19037BR1. doi: 10.4088/JCP.OT19037BR1

- Morris DW, Trivedi MH. Measurement-based care for unipolar depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(6):446-458.

- Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31. doi:10.4088/ JCP.8133su1c.04

- Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):324-335.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):73-82.

- Trivedi MH, Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, et al. Implementing measurement-based care to determine and treat inadequate response. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(3):OT19037BR1. doi: 10.4088/JCP.OT19037BR1

- Morris DW, Trivedi MH. Measurement-based care for unipolar depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(6):446-458.