User login

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

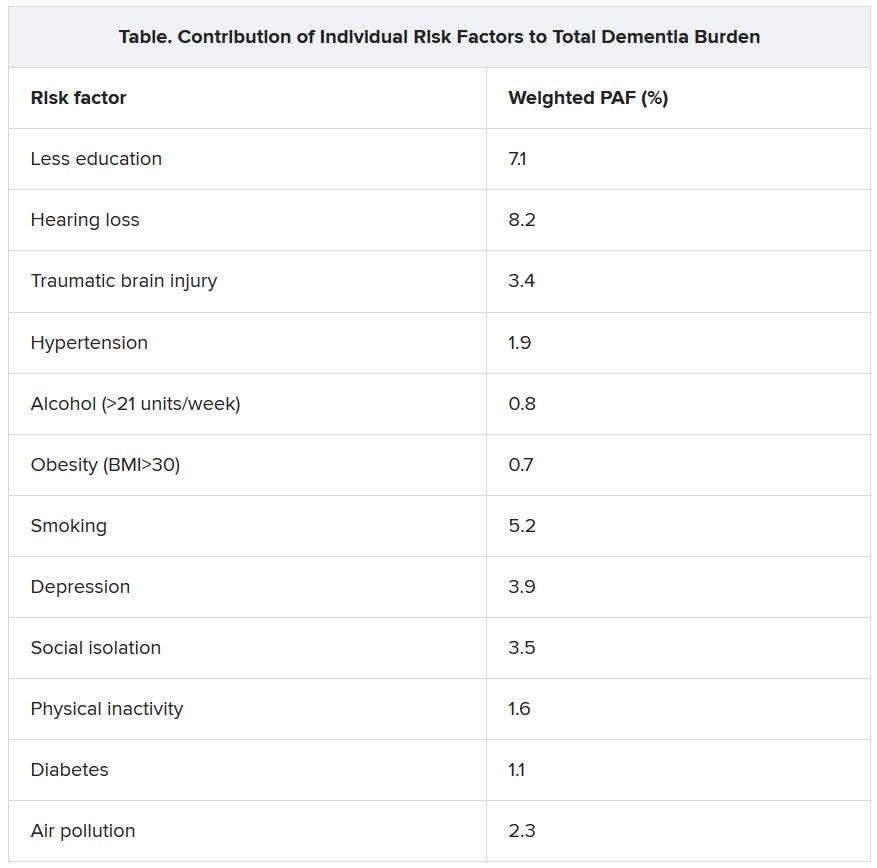

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2020