User login

In patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, lithium and anticonvulsants have become such common adjuncts to antipsychotics that 50% of inpatients may be receiving them.1 Evidence supporting this practice is mixed:

- Initial case reports and open-label studies that showed benefit have not always been followed by randomized clinical trials.

- Lack of clear benefit also has been described (Table 1).

This article examines the extent of this prescribing pattern, its evidence base, and mechanisms of action that may help explain why some adjunctive mood stabilizers are more effective than others for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

EXTENT OF USE

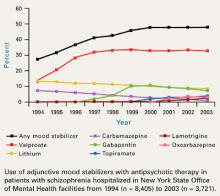

For 5 years, the rate at which inpatients with schizophrenia received adjunctive mood stabilizers has held steady at approximately 50% in New York State Office of Mental Health (NYSOMH) facilities (Figure1). These facilities provide intermediate and long-term care for the seriously, persistently mentally ill. Adjunctive mood stabilizers might not be used as often for outpatients or for inpatients treated in short-stay facilities.

Table 1

Evidence for adjunctive use of lithium or anticonvulsants for treating schizophrenia

| Agent | Case reports and open studies | Randomized, double-blind trials | Benefit? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | Yes (many) | Yes (several, +/-) | Probably not |

| Carbamazepine | Yes (many) | Yes (several; small total sample) | Limited |

| Valproate | Yes (many) | Yes | Yes |

| Gabapentin | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| Lamotrigine | Yes (few, +/-) | Yes (2, +) | Yes |

| Topiramate | Yes (very few, +/-) | Yes (1, +/-) | Probably not |

| Oxcarbazepine | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| + = positive results | |||

| - = negative results | |||

| +/- = both positive and negative results | |||

Valproate is the most commonly used anticonvulsant, with one out of three patients with schizophrenia receiving it. Adjunctive gabapentin use is declining, probably because of inadequate efficacy—as will be discussed later. Use of adjunctive lamotrigine is expected to increase as more data become available on its usefulness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Clinicians are using substantial dosages of adjunctive mood stabilizers. During first-quarter 2004, average daily dosages for 4,788 NYSOMH patients (80% with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) receiving antipsychotics were:

- valproate, 1639 mg (n = 1921)

- gabapentin, 1524 mg (n = 303)

- oxcarbazepine, 1226 mg (n = 201)

- carbamazepine, 908 mg (n = 112)

- lithium, 894 mg (n = 715)

- topiramate, 234 mg (n = 269)

- lamotrigine, 204 mg (n = 231).2

Mood-stabilizer combinations were also used. Approximately one-half of patients receiving adjunctive mood stabilizers—with the exception of valproate—were receiving more than one. In patients receiving valproate, the rate of mood-stabilizer co-prescribing was about 25%.2

WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE?

Evidence supporting the use of adjunctive lithium or anticonvulsants to treat schizophrenia varies in quality and quantity (Table 1). Case reports and open studies offer the weakest evidence but can spur double-blind, randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Unfortunately, RCTs are not often done, and the published studies usually suffer from methodologic flaws such as:

- inadequate number of subjects (insufficient statistical power to detect differences)

- lack of control of confounds such as mood symptoms (seen when studies include patients with schizoaffective disorder)

- inadequate duration

- inappropriate target populations (patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia instead of persistent symptoms in treatment-resistant schizophrenia).

Because controlled trials of the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers are relatively scarce, clinical practice has transcended clinical research. Clinicians need effective regimens for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and mood-stabilizer augmentation helps some patients.

Lithium is perhaps the best-known mood stabilizer. Although early studies showed adjunctive lithium useful in treating schizophrenia, later and better-designed trials did not. The authors of a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (n = 611 in 20 studies) concluded that despite some evidence supporting the efficacy of lithium augmentation, overall results were inconclusive. A large trial would be required to detect a small benefit in patients with schizophrenia who lack affective symptoms.3

Carbamazepine use among patients with schizophrenia is declining, primarily because this drug induces its own metabolism and can require frequent dose adjustments. Adjunctive carbamazepine has been used to manage persistent aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Evidence comes primarily from small trials or case reports (Table 2),4-8 but results of a larger clinical trial (n = 162) by Okuma et al6 are also available

In the Okuma report—a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of carbamazepine in patients with DSM-III schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder—carbamazepine did not significantly improve patients’ total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores. Compared with placebo, however, some benefit with carbamazepine did emerge in measures of suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 283 in 10 studies) detected a trend toward reduced psychopathology with carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia. BPRS scores declined by 20% and 35% in the six trials (n = 147) for which data were available (P = 0.08 and 0.09, respectively).9 Because the double-blind trial by Okuma et al6 was not randomized, it was not included in this meta-analysis.9

Figure 1 10-year trend in use of adjunctive mood stabilizers for schizophrenia

Valproate. Among the anticonvulsants, the greatest body of evidence supports the use of valproate in patients with schizophrenia,10 although a recent meta-analysis (n = 378 in 5 studies) indicates inconsistent beneficial effects.11

Initial double-blind, RCTs of adjunctive valproate in patients with schizophrenia were limited in size and failed to show benefit with adjunctive valproate12-15 (Table 2). A more recent study16 showed that adjunctive valproate affects acute psychotic symptoms rather than mood. This study, however, did not answer whether adjunctive valproate would help patients with persistent symptoms of schizophrenia.

Table 2

Double-blind studies of adjunctive carbamazepine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neppe (1983) | 11 | 42 | Crossover | Mixed, 8 with schizophrenia | “Overall clinical rating” improved |

| Dose et al (1987) | 22 | 28 | HAL + CBZ vs HAL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS |

| Okuma et al (1989) | 162 | 28 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS; possible improvement in suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement |

| Nachshoni et al (1994) | 28 | 49 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | “Residual schizophrenia with negative symptoms” | No difference on BPRS or SANS |

| Simhandl et al (1996) | 42 | 42 | NL + CBZ vs NL + lithium vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia(treatment- nonresponsive) | No difference on BPRS; CGI improved from baseline in groups receiving CBZ and lithium |

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| CBZ = carbamazepine | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| NL = neuroleptic (first-generation antipsychotic) | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In this large (n = 249), multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial, hospitalized patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia received olanzapine or risperidone plus divalproex or placebo for 28 days. Patients with schizoaffective disorder and treatment-resistant schizophrenia were excluded.

By day 6, dosages reached 6 mg/d for risperidone and 15 mg/d for olanzapine. Divalproex was started at 15 mg/kg and titrated to a maximum of 30 mg/kg by day 14. Mean divalproex dosage was approximately 2300 mg/d (mean plasma level approximately 100 mg/mL).

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores improved significantly in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with those receiving antipsychotic monotherapy, and significant differences occurred as early as day 3. The major effect was seen on schizophrenia’s positive symptoms. A post-hoc analysis17 also showed greater reductions in hostility (as measured by the hostility item in the PANSS Positive Subscale) in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with antipsychotic monotherapy. This effect was independent of the effect on positive symptoms or sedation.

A large, multi-site, 84-day acute schizophrenia RCT similar to the 28-day trial—but using extended-release divalproex—is being conducted. An extended-release preparation may be particularly helpful in encouraging medication adherence for patients taking complicated medication regimens.

Table 3

Double-blind studies of adjunctive valproate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ko et al (1985) | 6 | 28 | Crossover | Neurolepticresistant patients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | No valproate effect noted |

| Fisk and York (1987) | 62 | 42 | Antipsychotic + valproate vs antipsychotic + placebo | Chronic psychosis and tardive dyskinesia | No differences in mental state and behavior, as measured by“ Krawiecka scale”* |

| Dose et al (1998) | 42 | 28 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute, nonmanic schizophrenic or schizoaffective psychosis | No difference on BPRS; possible effect on “hostile belligerence” |

| Wassef et al (2000) | 12 | 21 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute exacerbation of chronic schizophrenia | CGI and SANS scores improved significantly, but BPRS scores did not |

| Casey et al (2003) | 249 | 28 | RIS + valproate vs OLZ + valproate vs RIS + placebo vs OLZ + placebo | Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia | PANSS scores improved |

| * Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1977;55(4):299-308. | |||||

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| OLZ = olanzapine | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| RIS = risperidone | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In a recent large (n = 10,262), retrospective, pharmacoepidemiologic analysis,18 valproate augmentation led to longer persistence of treatment than did the strategy of switching antipsychotics. Average valproate dosages were small, however (<425 mg/d), as were antipsychotic dosages (risperidone <1.7 mg/d, quetiapine <120 mg/d, and olanzapine <7.5 mg/d). Patients’ diagnostic categories were not available. One interpretation of this study is that valproate augmentation would be more successful than switching antipsychotics, assuming that treatment persistence can be viewed as a positive outcome.

Table 4

Double-blind studies of adjunctive lamotrigine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen et al (2003) | 34 | 84 | Crossover; clozapine with or without lamotrigine | Clozapine-resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | BPRS, PANSS positive, and PANSS general psychopathology symptom scores improved Negative symptoms did not improve |

| Kremer et al (2004) | 38 | 70 | Antipsychotic* + lamotrigine vs antipsychotic* + placebo | Treatment- resistant inpatients with schizophrenia | Completers’ PANSS positive, general psychopathology and total symptom scores improved No difference in negative symptoms or total BPRS scores No difference with intent-to-treat analyses |

| n = number of patients | |||||

| * First- or second-generation antipsychotic | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

Lamotrigine is the only other anticonvulsant for which published, double-blind, randomized evidence of use in patients with schizophrenia is available (Table 4).19,20 Adjunctive lamotrigine may be effective in managing treatment-resistant schizophrenia, as was shown in a small (n = 34), double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial.19 Hospitalized patients whose symptoms were inadequately controlled with clozapine monotherapy received lamotrigine, 200 mg/d, for up to 12 weeks. Adjunctive lamotrigine improved positive but not negative symptoms.

Similar results were seen in treatment-resistant inpatients with schizophrenia (n = 38) in a 10-week, double-blind, parallel group trial by Kremer et al.20 Adjunctive lamotrigine improved PANSS positive, general psychopathology, and total symptom scores in the 31 patients who completed the trial. No differences were seen, however, in negative symptoms, total BPRS scores, or in the intent-to-treat analysis. These results have spurred the launch of a large, multi-site, RCT of adjunctive lamotrigine in patients with schizophrenia who have responded inadequately to antipsychotics alone.

Topiramate, one of the few psychotropics associated with weight loss, has attracted interest as an adjunct to second-generation antipsychotics to address weight gain. Although case reports have shown benefit,21 one showed deterioration in both positive and negative symptoms when topiramate was added to second-generation antipsychotics.22

Table 5

Double-blind study of adjunctive topiramate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen (2004)* | 26 | 84 | Crossover; SGA plus topiramate or placebo | Treatment- resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia | PANSS general scores improved No difference in total PANSS, PANSS positive, or PANSS negative scores |

| * 2004 Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP) presentation, and personal communication (6/22/04) | |||||

| n = number of patients | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| SGA = Second-generation antipsychotic (patients were taking clozapine, olanzapine, or quetiapine) | |||||

An unpublished, randomized, crossover trial compared second-generation antipsychotics plus topiramate or placebo in 26 male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. With adjunctive topiramate, the authors found a statistically significant improvement in the PANSS general psychopathology subscale but not in PANSS total, positive subscale, or negative subscale scores (Table 5) (Tiihonen J, personal communication 6/22/04).

Other agents. Very little information—all uncontrolled—supports adjunctive use of gabapentin or oxcarbazepine for patients with schizophrenia.23-28 Of concern are reports of patients suffering worsening of psychosis with gabapentin25 or of dysphoria and irritability with oxcarbazepine (attributed to a pharmacokinetic interaction).26

Conclusion. More trials are needed to examine the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers in patients with schizophrenia—particularly in those with chronic symptoms. Although mood stabilizers are widely used in this population, important questions remain unanswered, including:

- characteristics of patients likely to require adjunctive treatment

- how long treatment should continue.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

Unlike antipsychotics, mood stabilizers do not exert their therapeutic effects by acting directly on dopamine (D2) receptors. Differences in mechanism of action among the anticonvulsants may help explain why some—such as valproate and lamotrigine—have been useful for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and others—such as gabapentin—have not.29

One possibility is that anticonvulsants that affect voltage-gated sodium channels—such as valproate, lamotrigine, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine—may be most useful for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. On the other hand, agents that affect voltage-gated calcium channels—such as gabapentin—may be efficacious as anticonvulsants but not as efficacious for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Ketter et al30 proposed an anticonvulsant classification system based on predominant psychotropic profiles:

- the “GABA-ergic” group predominantly potentiates the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, resulting in sedation, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and weight gain, as well as possible anxiolytic and antimanic effects

- the “anti-glutamate” group predominantly attenuates glutamate excitatory neurotransmission and is associated with activation, weight loss, and possibly anxiogenic and antidepressant effects.

In the GABA-ergic group are anticonvulsants such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, valproate, gabapentin, tiagabine, and vigabatrin. The antiglutamate group includes agents such as felbamate and lamotrigine. A “mixed” category includes anticonvulsants with GABA-ergic and anti-glutaminergic actions such as topiramate, which has sedating and weight-loss properties.

Because GABA appears to modulate dopamine neurotransmission,31 this may explain valproate’s role as an adjunctive agent for schizophrenia. Similarly, mechanisms related to Nmethyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA glutamate receptor function may explain lamotrigine’s usefulness in this setting.19,20

SUMMARY

Clinicians resort to combination therapies when monotherapies fail to adequately control symptoms or maintain response. Co-prescribing of anticonvulsants with antipsychotics for inpatients with schizophrenia is common practice in New York State and most likely elsewhere. In general, antipsychotics’ and mood stabilizers’ different—and perhaps complementary—mechanisms of action explain the synergism between them. Mechanisms of action also may explain why some anticonvulsants help in schizophrenia (or bipolar disorder) whereas others do not.

Evidence for using adjunctive anticonvulsants is variable. The strongest data support using valproate (and perhaps lamotrigine), followed by carbamazepine and then topiramate. Gabapentin and oxcarbazepine have only anecdotal evidence, some of it negative. Well-designed, randomized clinical trials with the appropriate populations are needed.

Related resources

- Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry’s psychopharmacology algorithm project. Osser DN, Patterson RD. Consultant for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Available at http://mhc.com/Algorithms/. Accessed Nov. 5, 2004.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Valproate (valproic acid, divalproex sodium) • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Citrome receives research grants/contracts from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to and/or speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Pfizer Inc., Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.

Acknowledgment

Adapted from Citrome L. “Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S. perspective” (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004; 7(suppl 1):S69], and from Citrome L. “Mood-stabilizer use in schizophrenia: 1994-2002” (NR350) (poster). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, May 2004.

1. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J. Datapoints - mood stabilizers: utilization trends in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia 1994-2001. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53(10):1212.-

2. Citrome L. Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S.perspective (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum(CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(suppl 1):S69].

3. Leucht S, Kissling W, McGrath J. Lithium for schizophrenia revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):177-86.

4. Neppe VM. Carbamazepine as adjunctive treatment in nonepileptic chronic inpatients with EEG temporal lobe abnormalities. J Clin Psychiatry 1983;44:326-31.

5. Dose M, Apelt S, Emrich HM. Carbamazepine as an adjunct of antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatry Res 1987;22:303-10.

6. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al. A double-blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:250-9.

7. Nachshoni T, Levin Y, Levy A, et al. A double-blind trial of carbamazepine in negative symptom schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994;35(1):22-26.

8. Simhandl C, Meszaros K, Denk E, et al. Adjunctive carbamazepine or lithium carbonate in therapy-resistant chronic schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41(5):317.-

9. Leucht S, McGrath J, White P, et al. Carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia: how good is the evidence? J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(3):218-24.

10. Citrome L. Schizophrenia and valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37(suppl 2):74-88.

11. Basan A, Kissling W, Leucht S. Valproate as an adjunct to antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized trials. Schizophr Res 2004;70(1):33-7.

12. Ko GN, Korpi ER, Freed WJ, et al. Effect of valproic acid on behavior and plasma amino acid concentrations in chronic schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry 1985;20:209-15.

13. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, et al. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998;31(4):122-5.

14. Fisk GG, York SM. The effect of sodium valproate on tardive dyskinesia—revisited. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:542-6.

15. Wassef AA, Dott SG, Harris A, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(3):357-361.

16. Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al. Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol 2003;28(1):182-92.

17. Citrome L, Casey DE, Daniel DG, et al. Effects of adjunctive valproate on hostility in patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or risperidone: a double-blind multi-center study. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(3):290-4.

18. Cramer JA, Sernyak M. Results of a naturalistic study of treatment options: switching atypical antipsychotic drugs or augmenting with valproate. Clin Ther 2004;26(6):905-14.

19. Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, et al. Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(11):1241-8.

20. Kremer I, Vass A, Gurelik I, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine added to conventional and atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2004;56(6):441-6.

21. Drapalski AL, Rosse RB, Peebles RR, et al. Topiramate improves deficit symptoms in a patient with schizophrenia when added to a stable regimen of antipsychotic medication. Clin Neuropharmacol 2001;24:290-4.

22. Millson RC, Owen JA, Lorberg GW, Tackaberry L. Topiramate for refractory schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(4):675.-

23. Chouinard G, Beauclair L, Belanger MC. Gabapentin: long term antianxiety and hypnotic effects in psychiatric patients with comorbid anxiety-related disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998;43:305.-

24. Megna JL, Devitt PJ, Sauro MD, Dewan MJ. Gabapentin’s effect on agitation in severely and persistently mentally ill patients. Ann Pharmacother 2002;35:12-16.

25. Jablonowski K, Margolese HC, Chouinard G. Gabapentin-induced paradoxical exacerbation of psychosis in a patient with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47(10):975-6.

26. Baird P. The interactive metabolism effect of oxcarbazepine coadministered with tricyclic antidepressant therapy for OCD symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):419.-

27. Centorrino F, Albert MJ, Berry JM, et al. Oxcarbazepine: clinical experience with hospitalized psychiatric patients. Bipolar Disord 2003;5(5):370-4.

28. Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, et al. Oxcarbazepine as an adjunct for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(6):1130-1.

29. Stahl SM. Psychopharmacology of anticonvulsants: do all anticonvulsants have the same mechanism of action? J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):149-50.

30. Ketter TA, Wong PW. The emerging differential roles of GABAergic and antiglutaminergic agents in bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 3):15-20.

31. Wassef A, Baker J, Kochan LD. GABA and schizophrenia: a review of basic science and clinical studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(6):601-40.

In patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, lithium and anticonvulsants have become such common adjuncts to antipsychotics that 50% of inpatients may be receiving them.1 Evidence supporting this practice is mixed:

- Initial case reports and open-label studies that showed benefit have not always been followed by randomized clinical trials.

- Lack of clear benefit also has been described (Table 1).

This article examines the extent of this prescribing pattern, its evidence base, and mechanisms of action that may help explain why some adjunctive mood stabilizers are more effective than others for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

EXTENT OF USE

For 5 years, the rate at which inpatients with schizophrenia received adjunctive mood stabilizers has held steady at approximately 50% in New York State Office of Mental Health (NYSOMH) facilities (Figure1). These facilities provide intermediate and long-term care for the seriously, persistently mentally ill. Adjunctive mood stabilizers might not be used as often for outpatients or for inpatients treated in short-stay facilities.

Table 1

Evidence for adjunctive use of lithium or anticonvulsants for treating schizophrenia

| Agent | Case reports and open studies | Randomized, double-blind trials | Benefit? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | Yes (many) | Yes (several, +/-) | Probably not |

| Carbamazepine | Yes (many) | Yes (several; small total sample) | Limited |

| Valproate | Yes (many) | Yes | Yes |

| Gabapentin | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| Lamotrigine | Yes (few, +/-) | Yes (2, +) | Yes |

| Topiramate | Yes (very few, +/-) | Yes (1, +/-) | Probably not |

| Oxcarbazepine | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| + = positive results | |||

| - = negative results | |||

| +/- = both positive and negative results | |||

Valproate is the most commonly used anticonvulsant, with one out of three patients with schizophrenia receiving it. Adjunctive gabapentin use is declining, probably because of inadequate efficacy—as will be discussed later. Use of adjunctive lamotrigine is expected to increase as more data become available on its usefulness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Clinicians are using substantial dosages of adjunctive mood stabilizers. During first-quarter 2004, average daily dosages for 4,788 NYSOMH patients (80% with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) receiving antipsychotics were:

- valproate, 1639 mg (n = 1921)

- gabapentin, 1524 mg (n = 303)

- oxcarbazepine, 1226 mg (n = 201)

- carbamazepine, 908 mg (n = 112)

- lithium, 894 mg (n = 715)

- topiramate, 234 mg (n = 269)

- lamotrigine, 204 mg (n = 231).2

Mood-stabilizer combinations were also used. Approximately one-half of patients receiving adjunctive mood stabilizers—with the exception of valproate—were receiving more than one. In patients receiving valproate, the rate of mood-stabilizer co-prescribing was about 25%.2

WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE?

Evidence supporting the use of adjunctive lithium or anticonvulsants to treat schizophrenia varies in quality and quantity (Table 1). Case reports and open studies offer the weakest evidence but can spur double-blind, randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Unfortunately, RCTs are not often done, and the published studies usually suffer from methodologic flaws such as:

- inadequate number of subjects (insufficient statistical power to detect differences)

- lack of control of confounds such as mood symptoms (seen when studies include patients with schizoaffective disorder)

- inadequate duration

- inappropriate target populations (patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia instead of persistent symptoms in treatment-resistant schizophrenia).

Because controlled trials of the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers are relatively scarce, clinical practice has transcended clinical research. Clinicians need effective regimens for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and mood-stabilizer augmentation helps some patients.

Lithium is perhaps the best-known mood stabilizer. Although early studies showed adjunctive lithium useful in treating schizophrenia, later and better-designed trials did not. The authors of a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (n = 611 in 20 studies) concluded that despite some evidence supporting the efficacy of lithium augmentation, overall results were inconclusive. A large trial would be required to detect a small benefit in patients with schizophrenia who lack affective symptoms.3

Carbamazepine use among patients with schizophrenia is declining, primarily because this drug induces its own metabolism and can require frequent dose adjustments. Adjunctive carbamazepine has been used to manage persistent aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Evidence comes primarily from small trials or case reports (Table 2),4-8 but results of a larger clinical trial (n = 162) by Okuma et al6 are also available

In the Okuma report—a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of carbamazepine in patients with DSM-III schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder—carbamazepine did not significantly improve patients’ total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores. Compared with placebo, however, some benefit with carbamazepine did emerge in measures of suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 283 in 10 studies) detected a trend toward reduced psychopathology with carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia. BPRS scores declined by 20% and 35% in the six trials (n = 147) for which data were available (P = 0.08 and 0.09, respectively).9 Because the double-blind trial by Okuma et al6 was not randomized, it was not included in this meta-analysis.9

Figure 1 10-year trend in use of adjunctive mood stabilizers for schizophrenia

Valproate. Among the anticonvulsants, the greatest body of evidence supports the use of valproate in patients with schizophrenia,10 although a recent meta-analysis (n = 378 in 5 studies) indicates inconsistent beneficial effects.11

Initial double-blind, RCTs of adjunctive valproate in patients with schizophrenia were limited in size and failed to show benefit with adjunctive valproate12-15 (Table 2). A more recent study16 showed that adjunctive valproate affects acute psychotic symptoms rather than mood. This study, however, did not answer whether adjunctive valproate would help patients with persistent symptoms of schizophrenia.

Table 2

Double-blind studies of adjunctive carbamazepine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neppe (1983) | 11 | 42 | Crossover | Mixed, 8 with schizophrenia | “Overall clinical rating” improved |

| Dose et al (1987) | 22 | 28 | HAL + CBZ vs HAL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS |

| Okuma et al (1989) | 162 | 28 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS; possible improvement in suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement |

| Nachshoni et al (1994) | 28 | 49 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | “Residual schizophrenia with negative symptoms” | No difference on BPRS or SANS |

| Simhandl et al (1996) | 42 | 42 | NL + CBZ vs NL + lithium vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia(treatment- nonresponsive) | No difference on BPRS; CGI improved from baseline in groups receiving CBZ and lithium |

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| CBZ = carbamazepine | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| NL = neuroleptic (first-generation antipsychotic) | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In this large (n = 249), multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial, hospitalized patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia received olanzapine or risperidone plus divalproex or placebo for 28 days. Patients with schizoaffective disorder and treatment-resistant schizophrenia were excluded.

By day 6, dosages reached 6 mg/d for risperidone and 15 mg/d for olanzapine. Divalproex was started at 15 mg/kg and titrated to a maximum of 30 mg/kg by day 14. Mean divalproex dosage was approximately 2300 mg/d (mean plasma level approximately 100 mg/mL).

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores improved significantly in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with those receiving antipsychotic monotherapy, and significant differences occurred as early as day 3. The major effect was seen on schizophrenia’s positive symptoms. A post-hoc analysis17 also showed greater reductions in hostility (as measured by the hostility item in the PANSS Positive Subscale) in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with antipsychotic monotherapy. This effect was independent of the effect on positive symptoms or sedation.

A large, multi-site, 84-day acute schizophrenia RCT similar to the 28-day trial—but using extended-release divalproex—is being conducted. An extended-release preparation may be particularly helpful in encouraging medication adherence for patients taking complicated medication regimens.

Table 3

Double-blind studies of adjunctive valproate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ko et al (1985) | 6 | 28 | Crossover | Neurolepticresistant patients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | No valproate effect noted |

| Fisk and York (1987) | 62 | 42 | Antipsychotic + valproate vs antipsychotic + placebo | Chronic psychosis and tardive dyskinesia | No differences in mental state and behavior, as measured by“ Krawiecka scale”* |

| Dose et al (1998) | 42 | 28 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute, nonmanic schizophrenic or schizoaffective psychosis | No difference on BPRS; possible effect on “hostile belligerence” |

| Wassef et al (2000) | 12 | 21 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute exacerbation of chronic schizophrenia | CGI and SANS scores improved significantly, but BPRS scores did not |

| Casey et al (2003) | 249 | 28 | RIS + valproate vs OLZ + valproate vs RIS + placebo vs OLZ + placebo | Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia | PANSS scores improved |

| * Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1977;55(4):299-308. | |||||

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| OLZ = olanzapine | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| RIS = risperidone | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In a recent large (n = 10,262), retrospective, pharmacoepidemiologic analysis,18 valproate augmentation led to longer persistence of treatment than did the strategy of switching antipsychotics. Average valproate dosages were small, however (<425 mg/d), as were antipsychotic dosages (risperidone <1.7 mg/d, quetiapine <120 mg/d, and olanzapine <7.5 mg/d). Patients’ diagnostic categories were not available. One interpretation of this study is that valproate augmentation would be more successful than switching antipsychotics, assuming that treatment persistence can be viewed as a positive outcome.

Table 4

Double-blind studies of adjunctive lamotrigine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen et al (2003) | 34 | 84 | Crossover; clozapine with or without lamotrigine | Clozapine-resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | BPRS, PANSS positive, and PANSS general psychopathology symptom scores improved Negative symptoms did not improve |

| Kremer et al (2004) | 38 | 70 | Antipsychotic* + lamotrigine vs antipsychotic* + placebo | Treatment- resistant inpatients with schizophrenia | Completers’ PANSS positive, general psychopathology and total symptom scores improved No difference in negative symptoms or total BPRS scores No difference with intent-to-treat analyses |

| n = number of patients | |||||

| * First- or second-generation antipsychotic | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

Lamotrigine is the only other anticonvulsant for which published, double-blind, randomized evidence of use in patients with schizophrenia is available (Table 4).19,20 Adjunctive lamotrigine may be effective in managing treatment-resistant schizophrenia, as was shown in a small (n = 34), double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial.19 Hospitalized patients whose symptoms were inadequately controlled with clozapine monotherapy received lamotrigine, 200 mg/d, for up to 12 weeks. Adjunctive lamotrigine improved positive but not negative symptoms.

Similar results were seen in treatment-resistant inpatients with schizophrenia (n = 38) in a 10-week, double-blind, parallel group trial by Kremer et al.20 Adjunctive lamotrigine improved PANSS positive, general psychopathology, and total symptom scores in the 31 patients who completed the trial. No differences were seen, however, in negative symptoms, total BPRS scores, or in the intent-to-treat analysis. These results have spurred the launch of a large, multi-site, RCT of adjunctive lamotrigine in patients with schizophrenia who have responded inadequately to antipsychotics alone.

Topiramate, one of the few psychotropics associated with weight loss, has attracted interest as an adjunct to second-generation antipsychotics to address weight gain. Although case reports have shown benefit,21 one showed deterioration in both positive and negative symptoms when topiramate was added to second-generation antipsychotics.22

Table 5

Double-blind study of adjunctive topiramate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen (2004)* | 26 | 84 | Crossover; SGA plus topiramate or placebo | Treatment- resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia | PANSS general scores improved No difference in total PANSS, PANSS positive, or PANSS negative scores |

| * 2004 Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP) presentation, and personal communication (6/22/04) | |||||

| n = number of patients | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| SGA = Second-generation antipsychotic (patients were taking clozapine, olanzapine, or quetiapine) | |||||

An unpublished, randomized, crossover trial compared second-generation antipsychotics plus topiramate or placebo in 26 male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. With adjunctive topiramate, the authors found a statistically significant improvement in the PANSS general psychopathology subscale but not in PANSS total, positive subscale, or negative subscale scores (Table 5) (Tiihonen J, personal communication 6/22/04).

Other agents. Very little information—all uncontrolled—supports adjunctive use of gabapentin or oxcarbazepine for patients with schizophrenia.23-28 Of concern are reports of patients suffering worsening of psychosis with gabapentin25 or of dysphoria and irritability with oxcarbazepine (attributed to a pharmacokinetic interaction).26

Conclusion. More trials are needed to examine the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers in patients with schizophrenia—particularly in those with chronic symptoms. Although mood stabilizers are widely used in this population, important questions remain unanswered, including:

- characteristics of patients likely to require adjunctive treatment

- how long treatment should continue.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

Unlike antipsychotics, mood stabilizers do not exert their therapeutic effects by acting directly on dopamine (D2) receptors. Differences in mechanism of action among the anticonvulsants may help explain why some—such as valproate and lamotrigine—have been useful for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and others—such as gabapentin—have not.29

One possibility is that anticonvulsants that affect voltage-gated sodium channels—such as valproate, lamotrigine, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine—may be most useful for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. On the other hand, agents that affect voltage-gated calcium channels—such as gabapentin—may be efficacious as anticonvulsants but not as efficacious for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Ketter et al30 proposed an anticonvulsant classification system based on predominant psychotropic profiles:

- the “GABA-ergic” group predominantly potentiates the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, resulting in sedation, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and weight gain, as well as possible anxiolytic and antimanic effects

- the “anti-glutamate” group predominantly attenuates glutamate excitatory neurotransmission and is associated with activation, weight loss, and possibly anxiogenic and antidepressant effects.

In the GABA-ergic group are anticonvulsants such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, valproate, gabapentin, tiagabine, and vigabatrin. The antiglutamate group includes agents such as felbamate and lamotrigine. A “mixed” category includes anticonvulsants with GABA-ergic and anti-glutaminergic actions such as topiramate, which has sedating and weight-loss properties.

Because GABA appears to modulate dopamine neurotransmission,31 this may explain valproate’s role as an adjunctive agent for schizophrenia. Similarly, mechanisms related to Nmethyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA glutamate receptor function may explain lamotrigine’s usefulness in this setting.19,20

SUMMARY

Clinicians resort to combination therapies when monotherapies fail to adequately control symptoms or maintain response. Co-prescribing of anticonvulsants with antipsychotics for inpatients with schizophrenia is common practice in New York State and most likely elsewhere. In general, antipsychotics’ and mood stabilizers’ different—and perhaps complementary—mechanisms of action explain the synergism between them. Mechanisms of action also may explain why some anticonvulsants help in schizophrenia (or bipolar disorder) whereas others do not.

Evidence for using adjunctive anticonvulsants is variable. The strongest data support using valproate (and perhaps lamotrigine), followed by carbamazepine and then topiramate. Gabapentin and oxcarbazepine have only anecdotal evidence, some of it negative. Well-designed, randomized clinical trials with the appropriate populations are needed.

Related resources

- Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry’s psychopharmacology algorithm project. Osser DN, Patterson RD. Consultant for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Available at http://mhc.com/Algorithms/. Accessed Nov. 5, 2004.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Valproate (valproic acid, divalproex sodium) • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Citrome receives research grants/contracts from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to and/or speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Pfizer Inc., Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.

Acknowledgment

Adapted from Citrome L. “Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S. perspective” (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004; 7(suppl 1):S69], and from Citrome L. “Mood-stabilizer use in schizophrenia: 1994-2002” (NR350) (poster). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, May 2004.

In patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, lithium and anticonvulsants have become such common adjuncts to antipsychotics that 50% of inpatients may be receiving them.1 Evidence supporting this practice is mixed:

- Initial case reports and open-label studies that showed benefit have not always been followed by randomized clinical trials.

- Lack of clear benefit also has been described (Table 1).

This article examines the extent of this prescribing pattern, its evidence base, and mechanisms of action that may help explain why some adjunctive mood stabilizers are more effective than others for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

EXTENT OF USE

For 5 years, the rate at which inpatients with schizophrenia received adjunctive mood stabilizers has held steady at approximately 50% in New York State Office of Mental Health (NYSOMH) facilities (Figure1). These facilities provide intermediate and long-term care for the seriously, persistently mentally ill. Adjunctive mood stabilizers might not be used as often for outpatients or for inpatients treated in short-stay facilities.

Table 1

Evidence for adjunctive use of lithium or anticonvulsants for treating schizophrenia

| Agent | Case reports and open studies | Randomized, double-blind trials | Benefit? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | Yes (many) | Yes (several, +/-) | Probably not |

| Carbamazepine | Yes (many) | Yes (several; small total sample) | Limited |

| Valproate | Yes (many) | Yes | Yes |

| Gabapentin | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| Lamotrigine | Yes (few, +/-) | Yes (2, +) | Yes |

| Topiramate | Yes (very few, +/-) | Yes (1, +/-) | Probably not |

| Oxcarbazepine | Yes (very few, +/-) | None | Probably not |

| + = positive results | |||

| - = negative results | |||

| +/- = both positive and negative results | |||

Valproate is the most commonly used anticonvulsant, with one out of three patients with schizophrenia receiving it. Adjunctive gabapentin use is declining, probably because of inadequate efficacy—as will be discussed later. Use of adjunctive lamotrigine is expected to increase as more data become available on its usefulness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Clinicians are using substantial dosages of adjunctive mood stabilizers. During first-quarter 2004, average daily dosages for 4,788 NYSOMH patients (80% with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) receiving antipsychotics were:

- valproate, 1639 mg (n = 1921)

- gabapentin, 1524 mg (n = 303)

- oxcarbazepine, 1226 mg (n = 201)

- carbamazepine, 908 mg (n = 112)

- lithium, 894 mg (n = 715)

- topiramate, 234 mg (n = 269)

- lamotrigine, 204 mg (n = 231).2

Mood-stabilizer combinations were also used. Approximately one-half of patients receiving adjunctive mood stabilizers—with the exception of valproate—were receiving more than one. In patients receiving valproate, the rate of mood-stabilizer co-prescribing was about 25%.2

WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE?

Evidence supporting the use of adjunctive lithium or anticonvulsants to treat schizophrenia varies in quality and quantity (Table 1). Case reports and open studies offer the weakest evidence but can spur double-blind, randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Unfortunately, RCTs are not often done, and the published studies usually suffer from methodologic flaws such as:

- inadequate number of subjects (insufficient statistical power to detect differences)

- lack of control of confounds such as mood symptoms (seen when studies include patients with schizoaffective disorder)

- inadequate duration

- inappropriate target populations (patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia instead of persistent symptoms in treatment-resistant schizophrenia).

Because controlled trials of the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers are relatively scarce, clinical practice has transcended clinical research. Clinicians need effective regimens for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and mood-stabilizer augmentation helps some patients.

Lithium is perhaps the best-known mood stabilizer. Although early studies showed adjunctive lithium useful in treating schizophrenia, later and better-designed trials did not. The authors of a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (n = 611 in 20 studies) concluded that despite some evidence supporting the efficacy of lithium augmentation, overall results were inconclusive. A large trial would be required to detect a small benefit in patients with schizophrenia who lack affective symptoms.3

Carbamazepine use among patients with schizophrenia is declining, primarily because this drug induces its own metabolism and can require frequent dose adjustments. Adjunctive carbamazepine has been used to manage persistent aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Evidence comes primarily from small trials or case reports (Table 2),4-8 but results of a larger clinical trial (n = 162) by Okuma et al6 are also available

In the Okuma report—a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of carbamazepine in patients with DSM-III schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder—carbamazepine did not significantly improve patients’ total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores. Compared with placebo, however, some benefit with carbamazepine did emerge in measures of suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 283 in 10 studies) detected a trend toward reduced psychopathology with carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia. BPRS scores declined by 20% and 35% in the six trials (n = 147) for which data were available (P = 0.08 and 0.09, respectively).9 Because the double-blind trial by Okuma et al6 was not randomized, it was not included in this meta-analysis.9

Figure 1 10-year trend in use of adjunctive mood stabilizers for schizophrenia

Valproate. Among the anticonvulsants, the greatest body of evidence supports the use of valproate in patients with schizophrenia,10 although a recent meta-analysis (n = 378 in 5 studies) indicates inconsistent beneficial effects.11

Initial double-blind, RCTs of adjunctive valproate in patients with schizophrenia were limited in size and failed to show benefit with adjunctive valproate12-15 (Table 2). A more recent study16 showed that adjunctive valproate affects acute psychotic symptoms rather than mood. This study, however, did not answer whether adjunctive valproate would help patients with persistent symptoms of schizophrenia.

Table 2

Double-blind studies of adjunctive carbamazepine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neppe (1983) | 11 | 42 | Crossover | Mixed, 8 with schizophrenia | “Overall clinical rating” improved |

| Dose et al (1987) | 22 | 28 | HAL + CBZ vs HAL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS |

| Okuma et al (1989) | 162 | 28 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No difference on BPRS; possible improvement in suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, and excitement |

| Nachshoni et al (1994) | 28 | 49 | NL + CBZ vs NL + placebo | “Residual schizophrenia with negative symptoms” | No difference on BPRS or SANS |

| Simhandl et al (1996) | 42 | 42 | NL + CBZ vs NL + lithium vs NL + placebo | Schizophrenia(treatment- nonresponsive) | No difference on BPRS; CGI improved from baseline in groups receiving CBZ and lithium |

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| CBZ = carbamazepine | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| NL = neuroleptic (first-generation antipsychotic) | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In this large (n = 249), multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial, hospitalized patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia received olanzapine or risperidone plus divalproex or placebo for 28 days. Patients with schizoaffective disorder and treatment-resistant schizophrenia were excluded.

By day 6, dosages reached 6 mg/d for risperidone and 15 mg/d for olanzapine. Divalproex was started at 15 mg/kg and titrated to a maximum of 30 mg/kg by day 14. Mean divalproex dosage was approximately 2300 mg/d (mean plasma level approximately 100 mg/mL).

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores improved significantly in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with those receiving antipsychotic monotherapy, and significant differences occurred as early as day 3. The major effect was seen on schizophrenia’s positive symptoms. A post-hoc analysis17 also showed greater reductions in hostility (as measured by the hostility item in the PANSS Positive Subscale) in patients receiving adjunctive divalproex compared with antipsychotic monotherapy. This effect was independent of the effect on positive symptoms or sedation.

A large, multi-site, 84-day acute schizophrenia RCT similar to the 28-day trial—but using extended-release divalproex—is being conducted. An extended-release preparation may be particularly helpful in encouraging medication adherence for patients taking complicated medication regimens.

Table 3

Double-blind studies of adjunctive valproate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ko et al (1985) | 6 | 28 | Crossover | Neurolepticresistant patients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | No valproate effect noted |

| Fisk and York (1987) | 62 | 42 | Antipsychotic + valproate vs antipsychotic + placebo | Chronic psychosis and tardive dyskinesia | No differences in mental state and behavior, as measured by“ Krawiecka scale”* |

| Dose et al (1998) | 42 | 28 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute, nonmanic schizophrenic or schizoaffective psychosis | No difference on BPRS; possible effect on “hostile belligerence” |

| Wassef et al (2000) | 12 | 21 | HAL + valproate vs HAL + placebo | Acute exacerbation of chronic schizophrenia | CGI and SANS scores improved significantly, but BPRS scores did not |

| Casey et al (2003) | 249 | 28 | RIS + valproate vs OLZ + valproate vs RIS + placebo vs OLZ + placebo | Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia | PANSS scores improved |

| * Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1977;55(4):299-308. | |||||

| n = number of subjects | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| CGI = Clinical Global Impression scale | |||||

| HAL = haloperidol | |||||

| OLZ = olanzapine | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| RIS = risperidone | |||||

| SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | |||||

In a recent large (n = 10,262), retrospective, pharmacoepidemiologic analysis,18 valproate augmentation led to longer persistence of treatment than did the strategy of switching antipsychotics. Average valproate dosages were small, however (<425 mg/d), as were antipsychotic dosages (risperidone <1.7 mg/d, quetiapine <120 mg/d, and olanzapine <7.5 mg/d). Patients’ diagnostic categories were not available. One interpretation of this study is that valproate augmentation would be more successful than switching antipsychotics, assuming that treatment persistence can be viewed as a positive outcome.

Table 4

Double-blind studies of adjunctive lamotrigine in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen et al (2003) | 34 | 84 | Crossover; clozapine with or without lamotrigine | Clozapine-resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, not exacerbation | BPRS, PANSS positive, and PANSS general psychopathology symptom scores improved Negative symptoms did not improve |

| Kremer et al (2004) | 38 | 70 | Antipsychotic* + lamotrigine vs antipsychotic* + placebo | Treatment- resistant inpatients with schizophrenia | Completers’ PANSS positive, general psychopathology and total symptom scores improved No difference in negative symptoms or total BPRS scores No difference with intent-to-treat analyses |

| n = number of patients | |||||

| * First- or second-generation antipsychotic | |||||

| BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

Lamotrigine is the only other anticonvulsant for which published, double-blind, randomized evidence of use in patients with schizophrenia is available (Table 4).19,20 Adjunctive lamotrigine may be effective in managing treatment-resistant schizophrenia, as was shown in a small (n = 34), double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial.19 Hospitalized patients whose symptoms were inadequately controlled with clozapine monotherapy received lamotrigine, 200 mg/d, for up to 12 weeks. Adjunctive lamotrigine improved positive but not negative symptoms.

Similar results were seen in treatment-resistant inpatients with schizophrenia (n = 38) in a 10-week, double-blind, parallel group trial by Kremer et al.20 Adjunctive lamotrigine improved PANSS positive, general psychopathology, and total symptom scores in the 31 patients who completed the trial. No differences were seen, however, in negative symptoms, total BPRS scores, or in the intent-to-treat analysis. These results have spurred the launch of a large, multi-site, RCT of adjunctive lamotrigine in patients with schizophrenia who have responded inadequately to antipsychotics alone.

Topiramate, one of the few psychotropics associated with weight loss, has attracted interest as an adjunct to second-generation antipsychotics to address weight gain. Although case reports have shown benefit,21 one showed deterioration in both positive and negative symptoms when topiramate was added to second-generation antipsychotics.22

Table 5

Double-blind study of adjunctive topiramate in schizophrenia

| Author (yr) | n | Duration (days) | Design | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiihonen (2004)* | 26 | 84 | Crossover; SGA plus topiramate or placebo | Treatment- resistant male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia | PANSS general scores improved No difference in total PANSS, PANSS positive, or PANSS negative scores |

| * 2004 Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP) presentation, and personal communication (6/22/04) | |||||

| n = number of patients | |||||

| PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||

| SGA = Second-generation antipsychotic (patients were taking clozapine, olanzapine, or quetiapine) | |||||

An unpublished, randomized, crossover trial compared second-generation antipsychotics plus topiramate or placebo in 26 male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. With adjunctive topiramate, the authors found a statistically significant improvement in the PANSS general psychopathology subscale but not in PANSS total, positive subscale, or negative subscale scores (Table 5) (Tiihonen J, personal communication 6/22/04).

Other agents. Very little information—all uncontrolled—supports adjunctive use of gabapentin or oxcarbazepine for patients with schizophrenia.23-28 Of concern are reports of patients suffering worsening of psychosis with gabapentin25 or of dysphoria and irritability with oxcarbazepine (attributed to a pharmacokinetic interaction).26

Conclusion. More trials are needed to examine the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers in patients with schizophrenia—particularly in those with chronic symptoms. Although mood stabilizers are widely used in this population, important questions remain unanswered, including:

- characteristics of patients likely to require adjunctive treatment

- how long treatment should continue.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

Unlike antipsychotics, mood stabilizers do not exert their therapeutic effects by acting directly on dopamine (D2) receptors. Differences in mechanism of action among the anticonvulsants may help explain why some—such as valproate and lamotrigine—have been useful for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and others—such as gabapentin—have not.29

One possibility is that anticonvulsants that affect voltage-gated sodium channels—such as valproate, lamotrigine, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine—may be most useful for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. On the other hand, agents that affect voltage-gated calcium channels—such as gabapentin—may be efficacious as anticonvulsants but not as efficacious for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Ketter et al30 proposed an anticonvulsant classification system based on predominant psychotropic profiles:

- the “GABA-ergic” group predominantly potentiates the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, resulting in sedation, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and weight gain, as well as possible anxiolytic and antimanic effects

- the “anti-glutamate” group predominantly attenuates glutamate excitatory neurotransmission and is associated with activation, weight loss, and possibly anxiogenic and antidepressant effects.

In the GABA-ergic group are anticonvulsants such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, valproate, gabapentin, tiagabine, and vigabatrin. The antiglutamate group includes agents such as felbamate and lamotrigine. A “mixed” category includes anticonvulsants with GABA-ergic and anti-glutaminergic actions such as topiramate, which has sedating and weight-loss properties.

Because GABA appears to modulate dopamine neurotransmission,31 this may explain valproate’s role as an adjunctive agent for schizophrenia. Similarly, mechanisms related to Nmethyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA glutamate receptor function may explain lamotrigine’s usefulness in this setting.19,20

SUMMARY

Clinicians resort to combination therapies when monotherapies fail to adequately control symptoms or maintain response. Co-prescribing of anticonvulsants with antipsychotics for inpatients with schizophrenia is common practice in New York State and most likely elsewhere. In general, antipsychotics’ and mood stabilizers’ different—and perhaps complementary—mechanisms of action explain the synergism between them. Mechanisms of action also may explain why some anticonvulsants help in schizophrenia (or bipolar disorder) whereas others do not.

Evidence for using adjunctive anticonvulsants is variable. The strongest data support using valproate (and perhaps lamotrigine), followed by carbamazepine and then topiramate. Gabapentin and oxcarbazepine have only anecdotal evidence, some of it negative. Well-designed, randomized clinical trials with the appropriate populations are needed.

Related resources

- Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry’s psychopharmacology algorithm project. Osser DN, Patterson RD. Consultant for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Available at http://mhc.com/Algorithms/. Accessed Nov. 5, 2004.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Valproate (valproic acid, divalproex sodium) • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Citrome receives research grants/contracts from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to and/or speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly & Co., Pfizer Inc., Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.

Acknowledgment

Adapted from Citrome L. “Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S. perspective” (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum (CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004; 7(suppl 1):S69], and from Citrome L. “Mood-stabilizer use in schizophrenia: 1994-2002” (NR350) (poster). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, May 2004.

1. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J. Datapoints - mood stabilizers: utilization trends in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia 1994-2001. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53(10):1212.-

2. Citrome L. Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S.perspective (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum(CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(suppl 1):S69].

3. Leucht S, Kissling W, McGrath J. Lithium for schizophrenia revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):177-86.

4. Neppe VM. Carbamazepine as adjunctive treatment in nonepileptic chronic inpatients with EEG temporal lobe abnormalities. J Clin Psychiatry 1983;44:326-31.

5. Dose M, Apelt S, Emrich HM. Carbamazepine as an adjunct of antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatry Res 1987;22:303-10.

6. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al. A double-blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:250-9.

7. Nachshoni T, Levin Y, Levy A, et al. A double-blind trial of carbamazepine in negative symptom schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994;35(1):22-26.

8. Simhandl C, Meszaros K, Denk E, et al. Adjunctive carbamazepine or lithium carbonate in therapy-resistant chronic schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41(5):317.-

9. Leucht S, McGrath J, White P, et al. Carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia: how good is the evidence? J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(3):218-24.

10. Citrome L. Schizophrenia and valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37(suppl 2):74-88.

11. Basan A, Kissling W, Leucht S. Valproate as an adjunct to antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized trials. Schizophr Res 2004;70(1):33-7.

12. Ko GN, Korpi ER, Freed WJ, et al. Effect of valproic acid on behavior and plasma amino acid concentrations in chronic schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry 1985;20:209-15.

13. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, et al. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998;31(4):122-5.

14. Fisk GG, York SM. The effect of sodium valproate on tardive dyskinesia—revisited. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:542-6.

15. Wassef AA, Dott SG, Harris A, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(3):357-361.

16. Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al. Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol 2003;28(1):182-92.

17. Citrome L, Casey DE, Daniel DG, et al. Effects of adjunctive valproate on hostility in patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or risperidone: a double-blind multi-center study. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(3):290-4.

18. Cramer JA, Sernyak M. Results of a naturalistic study of treatment options: switching atypical antipsychotic drugs or augmenting with valproate. Clin Ther 2004;26(6):905-14.

19. Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, et al. Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(11):1241-8.

20. Kremer I, Vass A, Gurelik I, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine added to conventional and atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2004;56(6):441-6.

21. Drapalski AL, Rosse RB, Peebles RR, et al. Topiramate improves deficit symptoms in a patient with schizophrenia when added to a stable regimen of antipsychotic medication. Clin Neuropharmacol 2001;24:290-4.

22. Millson RC, Owen JA, Lorberg GW, Tackaberry L. Topiramate for refractory schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(4):675.-

23. Chouinard G, Beauclair L, Belanger MC. Gabapentin: long term antianxiety and hypnotic effects in psychiatric patients with comorbid anxiety-related disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998;43:305.-

24. Megna JL, Devitt PJ, Sauro MD, Dewan MJ. Gabapentin’s effect on agitation in severely and persistently mentally ill patients. Ann Pharmacother 2002;35:12-16.

25. Jablonowski K, Margolese HC, Chouinard G. Gabapentin-induced paradoxical exacerbation of psychosis in a patient with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47(10):975-6.

26. Baird P. The interactive metabolism effect of oxcarbazepine coadministered with tricyclic antidepressant therapy for OCD symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):419.-

27. Centorrino F, Albert MJ, Berry JM, et al. Oxcarbazepine: clinical experience with hospitalized psychiatric patients. Bipolar Disord 2003;5(5):370-4.

28. Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, et al. Oxcarbazepine as an adjunct for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(6):1130-1.

29. Stahl SM. Psychopharmacology of anticonvulsants: do all anticonvulsants have the same mechanism of action? J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):149-50.

30. Ketter TA, Wong PW. The emerging differential roles of GABAergic and antiglutaminergic agents in bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 3):15-20.

31. Wassef A, Baker J, Kochan LD. GABA and schizophrenia: a review of basic science and clinical studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(6):601-40.

1. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J. Datapoints - mood stabilizers: utilization trends in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia 1994-2001. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53(10):1212.-

2. Citrome L. Antipsychotic polypharmacy versus augmentation with anticonvulsants: the U.S.perspective (presentation). Paris: Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum(CINP), June 2004 [abstract in Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(suppl 1):S69].

3. Leucht S, Kissling W, McGrath J. Lithium for schizophrenia revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):177-86.

4. Neppe VM. Carbamazepine as adjunctive treatment in nonepileptic chronic inpatients with EEG temporal lobe abnormalities. J Clin Psychiatry 1983;44:326-31.

5. Dose M, Apelt S, Emrich HM. Carbamazepine as an adjunct of antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatry Res 1987;22:303-10.

6. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al. A double-blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:250-9.

7. Nachshoni T, Levin Y, Levy A, et al. A double-blind trial of carbamazepine in negative symptom schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994;35(1):22-26.

8. Simhandl C, Meszaros K, Denk E, et al. Adjunctive carbamazepine or lithium carbonate in therapy-resistant chronic schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41(5):317.-

9. Leucht S, McGrath J, White P, et al. Carbamazepine augmentation for schizophrenia: how good is the evidence? J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(3):218-24.

10. Citrome L. Schizophrenia and valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37(suppl 2):74-88.

11. Basan A, Kissling W, Leucht S. Valproate as an adjunct to antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized trials. Schizophr Res 2004;70(1):33-7.

12. Ko GN, Korpi ER, Freed WJ, et al. Effect of valproic acid on behavior and plasma amino acid concentrations in chronic schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry 1985;20:209-15.

13. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, et al. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998;31(4):122-5.

14. Fisk GG, York SM. The effect of sodium valproate on tardive dyskinesia—revisited. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:542-6.

15. Wassef AA, Dott SG, Harris A, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(3):357-361.

16. Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al. Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol 2003;28(1):182-92.

17. Citrome L, Casey DE, Daniel DG, et al. Effects of adjunctive valproate on hostility in patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or risperidone: a double-blind multi-center study. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(3):290-4.

18. Cramer JA, Sernyak M. Results of a naturalistic study of treatment options: switching atypical antipsychotic drugs or augmenting with valproate. Clin Ther 2004;26(6):905-14.

19. Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, et al. Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(11):1241-8.

20. Kremer I, Vass A, Gurelik I, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine added to conventional and atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2004;56(6):441-6.

21. Drapalski AL, Rosse RB, Peebles RR, et al. Topiramate improves deficit symptoms in a patient with schizophrenia when added to a stable regimen of antipsychotic medication. Clin Neuropharmacol 2001;24:290-4.

22. Millson RC, Owen JA, Lorberg GW, Tackaberry L. Topiramate for refractory schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(4):675.-

23. Chouinard G, Beauclair L, Belanger MC. Gabapentin: long term antianxiety and hypnotic effects in psychiatric patients with comorbid anxiety-related disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998;43:305.-

24. Megna JL, Devitt PJ, Sauro MD, Dewan MJ. Gabapentin’s effect on agitation in severely and persistently mentally ill patients. Ann Pharmacother 2002;35:12-16.

25. Jablonowski K, Margolese HC, Chouinard G. Gabapentin-induced paradoxical exacerbation of psychosis in a patient with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47(10):975-6.

26. Baird P. The interactive metabolism effect of oxcarbazepine coadministered with tricyclic antidepressant therapy for OCD symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):419.-

27. Centorrino F, Albert MJ, Berry JM, et al. Oxcarbazepine: clinical experience with hospitalized psychiatric patients. Bipolar Disord 2003;5(5):370-4.

28. Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, et al. Oxcarbazepine as an adjunct for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(6):1130-1.

29. Stahl SM. Psychopharmacology of anticonvulsants: do all anticonvulsants have the same mechanism of action? J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):149-50.

30. Ketter TA, Wong PW. The emerging differential roles of GABAergic and antiglutaminergic agents in bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 3):15-20.

31. Wassef A, Baker J, Kochan LD. GABA and schizophrenia: a review of basic science and clinical studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(6):601-40.