User login

As a physician living with bipolar disorder, I am more intimately familiar with the psychiatric ward than I would like to admit. Despite a decade of medication and weekly therapy, I live with a disease which flares, not unlike many of the patients I care for.

–Justin L Bullock, MD, MPH

Mental health conditions are common among physicians. Approximately 28% of residents experience depression or depressive symptoms during their training,1 and many will not seek mental health care due to fear of medical licensing implications.2 These fears are well-founded. Executive directors of 13 of 35 state medical boards indicated that diagnosis of mental illness alone was sufficient for sanctioning physicians.3 Another study found that two-thirds of state licensing applications pose questions about providers’ mental health that violate the American with Disabilities Act.2 What happens when a physician discloses and trusts the system to support their mental health–related needs? We address this question through the story of one trainee (JLB) recounting his experience with help-seeking and a fitness-for-duty (FFD) evaluation and conclude with recommendations to improve FFD processes.

Once again, I found myself sitting on a sheetless hospital bed with a baggy hospital gown draping my bony shoulders as I described my aborted suicide attempt to an attending psychiatrist. After a brief pause, the psychiatrist told me that they did not want to cause problems for my medical license and would drop my psychiatric hold. Even though they were the third psychiatrist to say this to me, their words caught me off guard given my recent attempt. I believe these psychiatrists factored my medical career into their clinical care because they understood that the simple act of being psychiatrically hospitalized placed my medical career in peril. After I completed a month-long outpatient treatment program, a psychiatrist and therapist cleared me to return to work.

I feel no shame about living with bipolar disorder and have always been transparent with my institution; the reason behind my absence was no secret. But before I could return to work, my case had to be reviewed by my institution’s Physician Well-being Committee. This committee was presented to me as a group that would help determine how to best support my return to work. However, before I had an opportunity to speak with the committee, I was informed that I would have to undergo a formal FFD evaluation.

FITNESS FOR DUTY

A FFD evaluation is indicated when there are credible reports of physician impairment or professional misconduct. Its purpose is to ensure that physicians can perform their essential job functions and that they are not a risk to patient safety. The Federation of State Medical Boards cautions that illness should not be conflated with impairment.4 Indeed, physicians with mental illness can function safely, thrive, and benefit patients and peers, especially when accommodations or modification reduce workplace barriers.5,6

I can best describe FFD as a 2-month-long stigmatized interrogation. I was forced to provide hair, blood, and urine samples for drug tests, complete an extensive multi-day psychiatric interview—including questions about my childhood trauma—and given a personality test. I was asked to disclose all of my private mental health records and feared I would be penalized if I refused to answer any questions. Multiple people, including my program director, confirmed that there were no performance or professionalism concerns. My suicide attempt happened outside of work; in my eyes, I had a mental illness which had been appropriately treated, not a workplace issue. I voiced my concern that the committee discriminated against me based on my mental illness. The committee told me that their decision to conduct a FFD was warranted because I had a condition that could affect my cognition, despite the lack of evidence that it actually had. My institution’s Office for Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination concurred that this was legal practice.

All of this happened despite my transparency regarding my bipolar disorder. Before I began residency, I disclosed my illness to my institution’s disability office, and I requested and received workplace accommodations. I have appropriately called-out of work whenever I felt that my bipolar could interfere with my focus on patient care. I have been openly bipolar and at the same institution for 6 years. In that time, I have received multiple teaching awards and a graduation award for exemplifying the qualities of a true physician—all while managing bipolar flares, including four hospitalizations. To destigmatize mental illness, I have discussed suicidality and getting help multiple times in front of hundreds of medical students.

The FFD evaluation found no evidence of a substance use disorder, nonadherence to treatment, or danger to my patients. Despite no adverse findings, and a record of well-managed mental illness and ongoing treatment, if I wanted to return to residency, I had to sign an agreement stipulating frequent monitoring by a “case-manager” and worksite “mentor.” I felt stigmatized and penalized for getting help. As I spoke out publicly against this process, I learned that my FFD experience is neither unique nor uncommon. Mental illness is deeply stigmatized within medicine. As a gay Black bipolar man, I hold multiple marginalized identities that inform and shape my experiences, yet the FFD committee did not have a single psychiatrist nor a single Black member. Instead, to make decisions on my case, they relied on the recommendations of the external psychiatrist, who met me for two days. In addition to the therapy and medications I had been taking for years, in order to return to work, I had to agree to a new type of therapy for the remainder of residency. I was incredulous that my employers felt it was appropriate to dictate my specific psychiatric care when I already had my own providers and my own care plan. My voice was not heard in this process, and despite my objections and the institutional mentors who spoke up for me, the FFD committee would not permit me to work without agreeing to their unmodified terms.

RE-ENVISIONING PHYSICIAN EVALUATION

Institutions face the challenging task of simultaneously navigating physician illness, patient safety, and institutional liability. In our opinion, many institutions excessively scrutinize physicians with mental illness and initiate FFD evaluations for reasons that are disproportionately skewed toward minimizing institutional liability. Moreover, in the absence of demonstrated physician workplace impairment, institutions should have systems in place to work collaboratively with the physician to ensure that they have access to professional treatment and appropriate workplace accommodations. It is possible to be simultaneously disabled and completely competent; creative and supportive accommodation processes allow physicians with disabilities to thrive, and their patients to benefit from the care of a physician with personal experience navigating disability. If a physician’s mental illness, despite accommodations, begins to impact workplace safety, a FFD evaluation may be initiated; unfortunately, the FFD evaluation itself may become a source of further harm.

FFD EVALUATIONS' POTENTIAL TO HARM PHYSICIANS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

FFD evaluations often situate the physician as incapable of managing their own mental illness, suggesting that they must be closely monitored and restricted even when physicians come forward independently.7 These beliefs and concurrent policies can propagate harmful, inaccurate biases against physicians who live with mental illness. These biases are compounded by the structural racism endemic in healthcare and academic medicine.8 Dehumanization in medicine adds fuel to this fire, projecting the ideal physician persona as an invulnerable, infallible superhuman who can witness intense suffering and work inhumane hours without impact upon the their mental health and well-being. Altogether, these factors increase fear and discourage help-seeking among physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure), ultimately harming physicians and patients in the process.9 Given that the FFD process involves evaluation, treatment, surveillance, and restrictions for individuals with stigmatized health conditions, these processes risk amplifying the impacts of trauma, racism, and oppression unless specifically designed to be antiracist, anti-oppressive, and trauma-informed.

TRAUMA-INFORMED APPROACH TO FFD

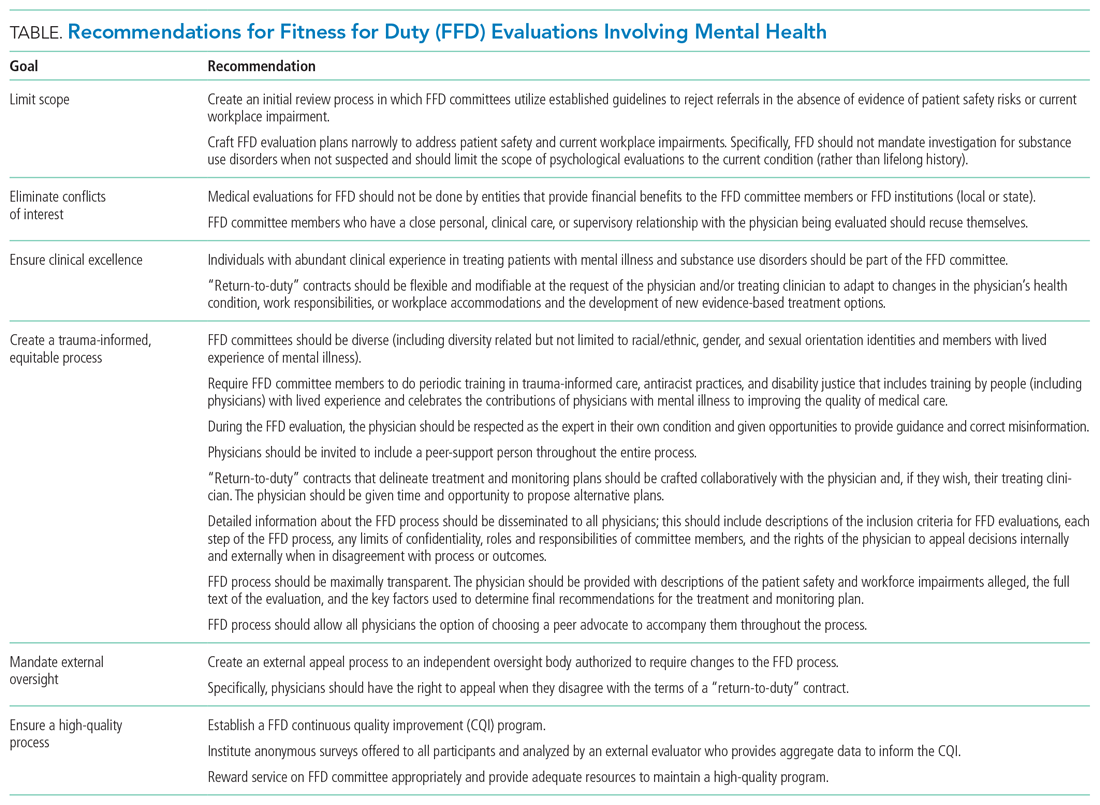

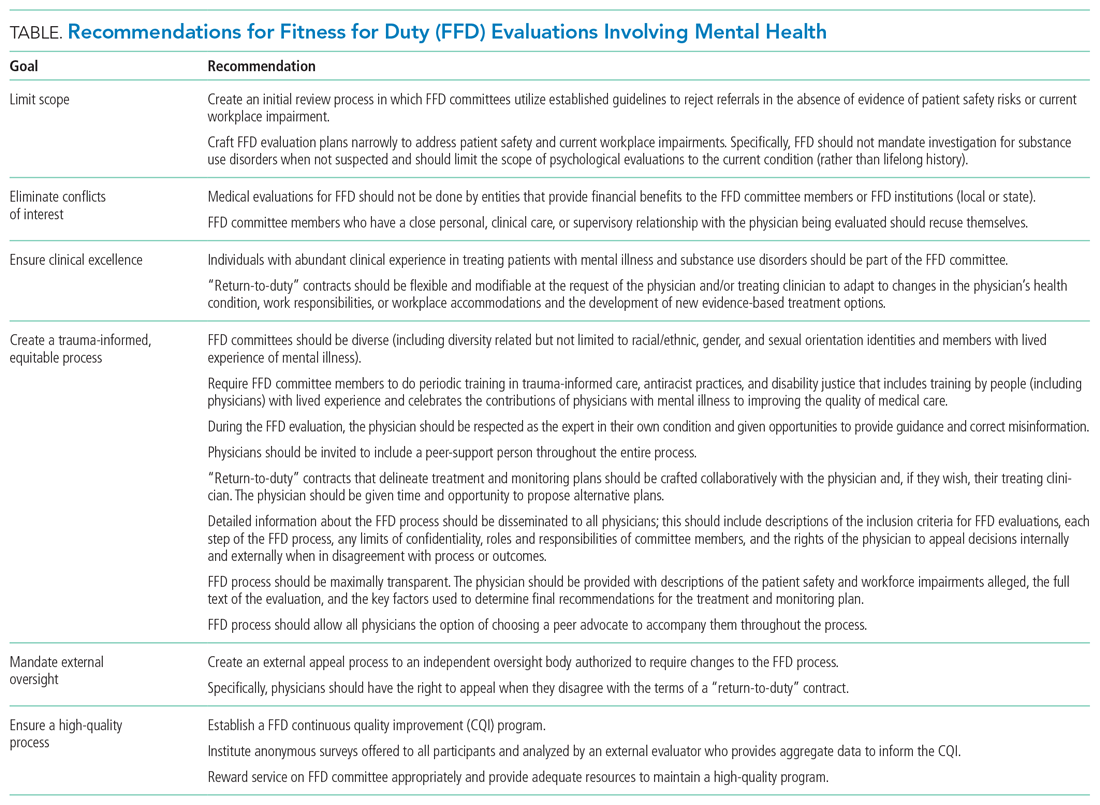

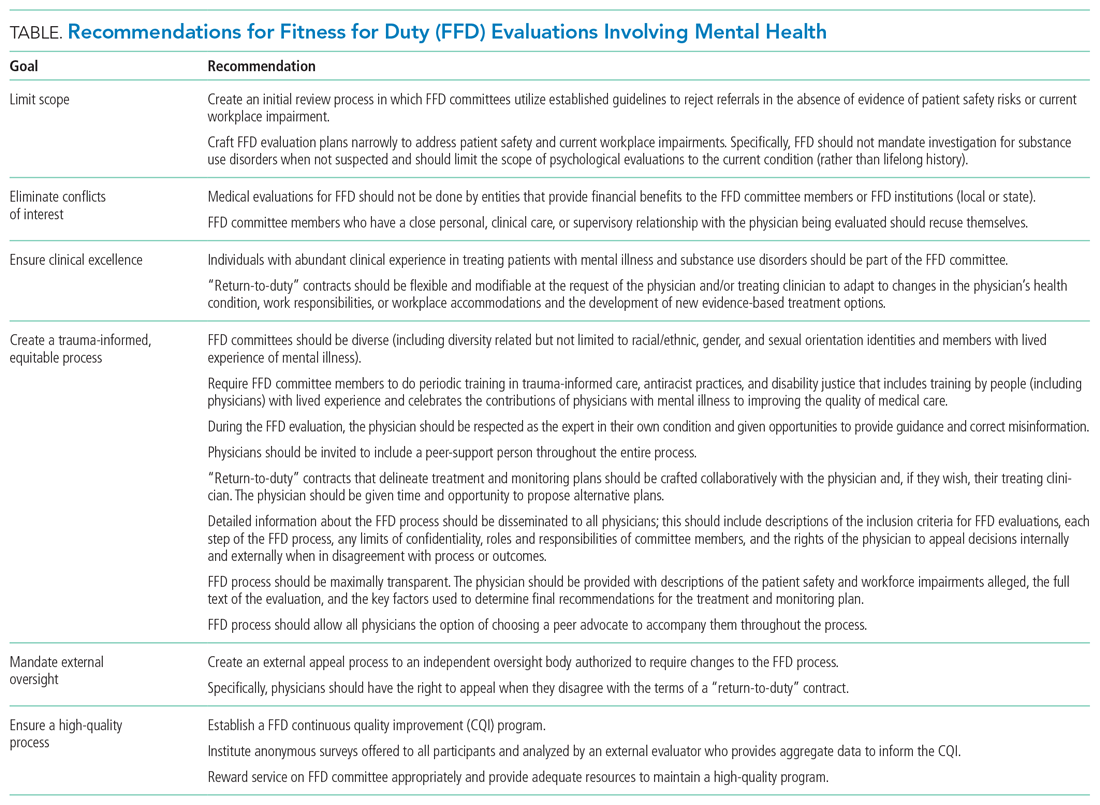

To encourage physician help-seeking, especially for stigmatized conditions, we must dismantle systems that traumatize physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure) and build systems that invite and support courageous vulnerability and help-seeking.5,6 Institutions can provide evaluation and oversight of physicians while also adopting trauma-informed care principles. A trauma-informed approach to FFD would ask: How can we create systems that are informed by a genuine understanding of suffering to promote healing and avoid re-traumatization? Trauma-informed care emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, transparency, cultural humility (an antiracist, anti-oppression framework), collaboration, peer support, and patient empowerment.10 FFD evaluations differ by institution and by state, with some being performed internally and others utilizing external state physician health programs. We believe our recommendations below apply independent of context (Table).

NECESSARY CHANGES

Institutional Changes

All institutions must publish a detailed description of the FFD process, including its purpose, the definition of impairment or potential impairment, and the steps of the FFD evaluation. The FFD evaluation should be as limited in scope as possible, without invasive inquiry about the physician’s life-long history. Physicians should be invited to include a peer-support person throughout the entire process. The FFD “return to work agreement” should incorporate meaningful input from the physician as the expert in their own experience and, if already in treatment, informed by their healthcare providers. Given the stigmatization of mental health conditions and inherent power differentials in FFD processes, it is paramount that committees be diverse (including but not limited to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and mental illness) and comprised of physicians trained in trauma-informed processes who treat the conditions affecting the individual undergoing the FFD evaluation. Finally, trustworthiness requires accountability: We recommend that all FFD systems establish an external oversight body that is equipped to effect change in real time if a physician reports a potential process violation and that collects anonymous feedback from physicians to inform required continuous quality improvement.

State and Federal Changes

It is difficult to effect meaningful change without accurate measurement of physician suicide. Therefore, we recommend mandatory reporting of physician suicide and suspected suicide to publicly available, de-identified state registries. We call for each state medical licensing board to limit licensing questions to current impairment due to mental illness, substance use disorders, or other health condition, as recommended by the Federation of State Medical Boards.4 There is a critical need for federal legislation to fund improvements in workplace safety and enhanced access to mental health treatment on demand for physicians.

Especially in these extraordinary times, as physicians are being exposed to such high burdens of stress, suffering, loss, and moral injury, we must de-stigmatize mental illness, encourage help-seeking, and provide physicians struggling with mental illness with timely and compassionate support. By creating systems that are healing and supportive for physicians, we enhance healing for all.

Bipolar is my sun and my storm. As a physician, I am not ashamed of that. For my own health and that of my patients, I must work in a system where it is safe to come forward when I am struggling.

As I fought against what I felt was a toxic and injurious process, I was fortunate to not stand alone. More than 600 residents from 18 departments at my institution signed a petition in support of reforming the FFD process informed by my experience. My institution is in the early stages of responding to this display of strength and unity with a diverse taskforce dedicated to improving the Physician Well-being Committee and FFD process.

As I accompany my patients on their healing journeys, my own experience with recovery allows me to hold the hope of healing for them. My family, friends, mentors, and providers held these rays of hope for me when I was lost in my own darkness. I now know that being cured from disease is just one form of healing. My proximity to death grounds me as some of my patients approach the end of life. Notably, some of my primary care patients have read my story online and come to their appointments to tell me that they are proud to have me as their doctor, “bipolar and all.”

1. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373-2383 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

2. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA, Goeders LE, Satele DV, Shanafelt TD. Medical Licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(10):1486-1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.020

3. Hendin H, Reynolds C, Fox D, et al. Licensing and physician mental health: problems and possibilities. J Med Licens Discip. 2007;93(2):6-11.

4. Federation of State Medical Boards. Physician wellness and burnout: report and recommendations of the workgroup on physician wellness and burnout. 2018. Accessed February 6, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and-burnout.pdf

5. Kirch D. Physician mental health: my personal journey and professional plea. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):618-620. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003942

6. Cho HL, Huang CJ. Why mental health–related stigma matters for physician wellbeing, burnout, and patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;24:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05173-6

7. Hill AB. Breaking the stigma - a physician’s perspective on self-care and recovery. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1103-1105. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1615974

8. Grubbs V. Diversity, equity, and inclusion that matter. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):e25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMpv2022639

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.292

10. Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. Center for Healthcare Strategy. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/

As a physician living with bipolar disorder, I am more intimately familiar with the psychiatric ward than I would like to admit. Despite a decade of medication and weekly therapy, I live with a disease which flares, not unlike many of the patients I care for.

–Justin L Bullock, MD, MPH

Mental health conditions are common among physicians. Approximately 28% of residents experience depression or depressive symptoms during their training,1 and many will not seek mental health care due to fear of medical licensing implications.2 These fears are well-founded. Executive directors of 13 of 35 state medical boards indicated that diagnosis of mental illness alone was sufficient for sanctioning physicians.3 Another study found that two-thirds of state licensing applications pose questions about providers’ mental health that violate the American with Disabilities Act.2 What happens when a physician discloses and trusts the system to support their mental health–related needs? We address this question through the story of one trainee (JLB) recounting his experience with help-seeking and a fitness-for-duty (FFD) evaluation and conclude with recommendations to improve FFD processes.

Once again, I found myself sitting on a sheetless hospital bed with a baggy hospital gown draping my bony shoulders as I described my aborted suicide attempt to an attending psychiatrist. After a brief pause, the psychiatrist told me that they did not want to cause problems for my medical license and would drop my psychiatric hold. Even though they were the third psychiatrist to say this to me, their words caught me off guard given my recent attempt. I believe these psychiatrists factored my medical career into their clinical care because they understood that the simple act of being psychiatrically hospitalized placed my medical career in peril. After I completed a month-long outpatient treatment program, a psychiatrist and therapist cleared me to return to work.

I feel no shame about living with bipolar disorder and have always been transparent with my institution; the reason behind my absence was no secret. But before I could return to work, my case had to be reviewed by my institution’s Physician Well-being Committee. This committee was presented to me as a group that would help determine how to best support my return to work. However, before I had an opportunity to speak with the committee, I was informed that I would have to undergo a formal FFD evaluation.

FITNESS FOR DUTY

A FFD evaluation is indicated when there are credible reports of physician impairment or professional misconduct. Its purpose is to ensure that physicians can perform their essential job functions and that they are not a risk to patient safety. The Federation of State Medical Boards cautions that illness should not be conflated with impairment.4 Indeed, physicians with mental illness can function safely, thrive, and benefit patients and peers, especially when accommodations or modification reduce workplace barriers.5,6

I can best describe FFD as a 2-month-long stigmatized interrogation. I was forced to provide hair, blood, and urine samples for drug tests, complete an extensive multi-day psychiatric interview—including questions about my childhood trauma—and given a personality test. I was asked to disclose all of my private mental health records and feared I would be penalized if I refused to answer any questions. Multiple people, including my program director, confirmed that there were no performance or professionalism concerns. My suicide attempt happened outside of work; in my eyes, I had a mental illness which had been appropriately treated, not a workplace issue. I voiced my concern that the committee discriminated against me based on my mental illness. The committee told me that their decision to conduct a FFD was warranted because I had a condition that could affect my cognition, despite the lack of evidence that it actually had. My institution’s Office for Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination concurred that this was legal practice.

All of this happened despite my transparency regarding my bipolar disorder. Before I began residency, I disclosed my illness to my institution’s disability office, and I requested and received workplace accommodations. I have appropriately called-out of work whenever I felt that my bipolar could interfere with my focus on patient care. I have been openly bipolar and at the same institution for 6 years. In that time, I have received multiple teaching awards and a graduation award for exemplifying the qualities of a true physician—all while managing bipolar flares, including four hospitalizations. To destigmatize mental illness, I have discussed suicidality and getting help multiple times in front of hundreds of medical students.

The FFD evaluation found no evidence of a substance use disorder, nonadherence to treatment, or danger to my patients. Despite no adverse findings, and a record of well-managed mental illness and ongoing treatment, if I wanted to return to residency, I had to sign an agreement stipulating frequent monitoring by a “case-manager” and worksite “mentor.” I felt stigmatized and penalized for getting help. As I spoke out publicly against this process, I learned that my FFD experience is neither unique nor uncommon. Mental illness is deeply stigmatized within medicine. As a gay Black bipolar man, I hold multiple marginalized identities that inform and shape my experiences, yet the FFD committee did not have a single psychiatrist nor a single Black member. Instead, to make decisions on my case, they relied on the recommendations of the external psychiatrist, who met me for two days. In addition to the therapy and medications I had been taking for years, in order to return to work, I had to agree to a new type of therapy for the remainder of residency. I was incredulous that my employers felt it was appropriate to dictate my specific psychiatric care when I already had my own providers and my own care plan. My voice was not heard in this process, and despite my objections and the institutional mentors who spoke up for me, the FFD committee would not permit me to work without agreeing to their unmodified terms.

RE-ENVISIONING PHYSICIAN EVALUATION

Institutions face the challenging task of simultaneously navigating physician illness, patient safety, and institutional liability. In our opinion, many institutions excessively scrutinize physicians with mental illness and initiate FFD evaluations for reasons that are disproportionately skewed toward minimizing institutional liability. Moreover, in the absence of demonstrated physician workplace impairment, institutions should have systems in place to work collaboratively with the physician to ensure that they have access to professional treatment and appropriate workplace accommodations. It is possible to be simultaneously disabled and completely competent; creative and supportive accommodation processes allow physicians with disabilities to thrive, and their patients to benefit from the care of a physician with personal experience navigating disability. If a physician’s mental illness, despite accommodations, begins to impact workplace safety, a FFD evaluation may be initiated; unfortunately, the FFD evaluation itself may become a source of further harm.

FFD EVALUATIONS' POTENTIAL TO HARM PHYSICIANS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

FFD evaluations often situate the physician as incapable of managing their own mental illness, suggesting that they must be closely monitored and restricted even when physicians come forward independently.7 These beliefs and concurrent policies can propagate harmful, inaccurate biases against physicians who live with mental illness. These biases are compounded by the structural racism endemic in healthcare and academic medicine.8 Dehumanization in medicine adds fuel to this fire, projecting the ideal physician persona as an invulnerable, infallible superhuman who can witness intense suffering and work inhumane hours without impact upon the their mental health and well-being. Altogether, these factors increase fear and discourage help-seeking among physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure), ultimately harming physicians and patients in the process.9 Given that the FFD process involves evaluation, treatment, surveillance, and restrictions for individuals with stigmatized health conditions, these processes risk amplifying the impacts of trauma, racism, and oppression unless specifically designed to be antiracist, anti-oppressive, and trauma-informed.

TRAUMA-INFORMED APPROACH TO FFD

To encourage physician help-seeking, especially for stigmatized conditions, we must dismantle systems that traumatize physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure) and build systems that invite and support courageous vulnerability and help-seeking.5,6 Institutions can provide evaluation and oversight of physicians while also adopting trauma-informed care principles. A trauma-informed approach to FFD would ask: How can we create systems that are informed by a genuine understanding of suffering to promote healing and avoid re-traumatization? Trauma-informed care emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, transparency, cultural humility (an antiracist, anti-oppression framework), collaboration, peer support, and patient empowerment.10 FFD evaluations differ by institution and by state, with some being performed internally and others utilizing external state physician health programs. We believe our recommendations below apply independent of context (Table).

NECESSARY CHANGES

Institutional Changes

All institutions must publish a detailed description of the FFD process, including its purpose, the definition of impairment or potential impairment, and the steps of the FFD evaluation. The FFD evaluation should be as limited in scope as possible, without invasive inquiry about the physician’s life-long history. Physicians should be invited to include a peer-support person throughout the entire process. The FFD “return to work agreement” should incorporate meaningful input from the physician as the expert in their own experience and, if already in treatment, informed by their healthcare providers. Given the stigmatization of mental health conditions and inherent power differentials in FFD processes, it is paramount that committees be diverse (including but not limited to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and mental illness) and comprised of physicians trained in trauma-informed processes who treat the conditions affecting the individual undergoing the FFD evaluation. Finally, trustworthiness requires accountability: We recommend that all FFD systems establish an external oversight body that is equipped to effect change in real time if a physician reports a potential process violation and that collects anonymous feedback from physicians to inform required continuous quality improvement.

State and Federal Changes

It is difficult to effect meaningful change without accurate measurement of physician suicide. Therefore, we recommend mandatory reporting of physician suicide and suspected suicide to publicly available, de-identified state registries. We call for each state medical licensing board to limit licensing questions to current impairment due to mental illness, substance use disorders, or other health condition, as recommended by the Federation of State Medical Boards.4 There is a critical need for federal legislation to fund improvements in workplace safety and enhanced access to mental health treatment on demand for physicians.

Especially in these extraordinary times, as physicians are being exposed to such high burdens of stress, suffering, loss, and moral injury, we must de-stigmatize mental illness, encourage help-seeking, and provide physicians struggling with mental illness with timely and compassionate support. By creating systems that are healing and supportive for physicians, we enhance healing for all.

Bipolar is my sun and my storm. As a physician, I am not ashamed of that. For my own health and that of my patients, I must work in a system where it is safe to come forward when I am struggling.

As I fought against what I felt was a toxic and injurious process, I was fortunate to not stand alone. More than 600 residents from 18 departments at my institution signed a petition in support of reforming the FFD process informed by my experience. My institution is in the early stages of responding to this display of strength and unity with a diverse taskforce dedicated to improving the Physician Well-being Committee and FFD process.

As I accompany my patients on their healing journeys, my own experience with recovery allows me to hold the hope of healing for them. My family, friends, mentors, and providers held these rays of hope for me when I was lost in my own darkness. I now know that being cured from disease is just one form of healing. My proximity to death grounds me as some of my patients approach the end of life. Notably, some of my primary care patients have read my story online and come to their appointments to tell me that they are proud to have me as their doctor, “bipolar and all.”

As a physician living with bipolar disorder, I am more intimately familiar with the psychiatric ward than I would like to admit. Despite a decade of medication and weekly therapy, I live with a disease which flares, not unlike many of the patients I care for.

–Justin L Bullock, MD, MPH

Mental health conditions are common among physicians. Approximately 28% of residents experience depression or depressive symptoms during their training,1 and many will not seek mental health care due to fear of medical licensing implications.2 These fears are well-founded. Executive directors of 13 of 35 state medical boards indicated that diagnosis of mental illness alone was sufficient for sanctioning physicians.3 Another study found that two-thirds of state licensing applications pose questions about providers’ mental health that violate the American with Disabilities Act.2 What happens when a physician discloses and trusts the system to support their mental health–related needs? We address this question through the story of one trainee (JLB) recounting his experience with help-seeking and a fitness-for-duty (FFD) evaluation and conclude with recommendations to improve FFD processes.

Once again, I found myself sitting on a sheetless hospital bed with a baggy hospital gown draping my bony shoulders as I described my aborted suicide attempt to an attending psychiatrist. After a brief pause, the psychiatrist told me that they did not want to cause problems for my medical license and would drop my psychiatric hold. Even though they were the third psychiatrist to say this to me, their words caught me off guard given my recent attempt. I believe these psychiatrists factored my medical career into their clinical care because they understood that the simple act of being psychiatrically hospitalized placed my medical career in peril. After I completed a month-long outpatient treatment program, a psychiatrist and therapist cleared me to return to work.

I feel no shame about living with bipolar disorder and have always been transparent with my institution; the reason behind my absence was no secret. But before I could return to work, my case had to be reviewed by my institution’s Physician Well-being Committee. This committee was presented to me as a group that would help determine how to best support my return to work. However, before I had an opportunity to speak with the committee, I was informed that I would have to undergo a formal FFD evaluation.

FITNESS FOR DUTY

A FFD evaluation is indicated when there are credible reports of physician impairment or professional misconduct. Its purpose is to ensure that physicians can perform their essential job functions and that they are not a risk to patient safety. The Federation of State Medical Boards cautions that illness should not be conflated with impairment.4 Indeed, physicians with mental illness can function safely, thrive, and benefit patients and peers, especially when accommodations or modification reduce workplace barriers.5,6

I can best describe FFD as a 2-month-long stigmatized interrogation. I was forced to provide hair, blood, and urine samples for drug tests, complete an extensive multi-day psychiatric interview—including questions about my childhood trauma—and given a personality test. I was asked to disclose all of my private mental health records and feared I would be penalized if I refused to answer any questions. Multiple people, including my program director, confirmed that there were no performance or professionalism concerns. My suicide attempt happened outside of work; in my eyes, I had a mental illness which had been appropriately treated, not a workplace issue. I voiced my concern that the committee discriminated against me based on my mental illness. The committee told me that their decision to conduct a FFD was warranted because I had a condition that could affect my cognition, despite the lack of evidence that it actually had. My institution’s Office for Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination concurred that this was legal practice.

All of this happened despite my transparency regarding my bipolar disorder. Before I began residency, I disclosed my illness to my institution’s disability office, and I requested and received workplace accommodations. I have appropriately called-out of work whenever I felt that my bipolar could interfere with my focus on patient care. I have been openly bipolar and at the same institution for 6 years. In that time, I have received multiple teaching awards and a graduation award for exemplifying the qualities of a true physician—all while managing bipolar flares, including four hospitalizations. To destigmatize mental illness, I have discussed suicidality and getting help multiple times in front of hundreds of medical students.

The FFD evaluation found no evidence of a substance use disorder, nonadherence to treatment, or danger to my patients. Despite no adverse findings, and a record of well-managed mental illness and ongoing treatment, if I wanted to return to residency, I had to sign an agreement stipulating frequent monitoring by a “case-manager” and worksite “mentor.” I felt stigmatized and penalized for getting help. As I spoke out publicly against this process, I learned that my FFD experience is neither unique nor uncommon. Mental illness is deeply stigmatized within medicine. As a gay Black bipolar man, I hold multiple marginalized identities that inform and shape my experiences, yet the FFD committee did not have a single psychiatrist nor a single Black member. Instead, to make decisions on my case, they relied on the recommendations of the external psychiatrist, who met me for two days. In addition to the therapy and medications I had been taking for years, in order to return to work, I had to agree to a new type of therapy for the remainder of residency. I was incredulous that my employers felt it was appropriate to dictate my specific psychiatric care when I already had my own providers and my own care plan. My voice was not heard in this process, and despite my objections and the institutional mentors who spoke up for me, the FFD committee would not permit me to work without agreeing to their unmodified terms.

RE-ENVISIONING PHYSICIAN EVALUATION

Institutions face the challenging task of simultaneously navigating physician illness, patient safety, and institutional liability. In our opinion, many institutions excessively scrutinize physicians with mental illness and initiate FFD evaluations for reasons that are disproportionately skewed toward minimizing institutional liability. Moreover, in the absence of demonstrated physician workplace impairment, institutions should have systems in place to work collaboratively with the physician to ensure that they have access to professional treatment and appropriate workplace accommodations. It is possible to be simultaneously disabled and completely competent; creative and supportive accommodation processes allow physicians with disabilities to thrive, and their patients to benefit from the care of a physician with personal experience navigating disability. If a physician’s mental illness, despite accommodations, begins to impact workplace safety, a FFD evaluation may be initiated; unfortunately, the FFD evaluation itself may become a source of further harm.

FFD EVALUATIONS' POTENTIAL TO HARM PHYSICIANS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

FFD evaluations often situate the physician as incapable of managing their own mental illness, suggesting that they must be closely monitored and restricted even when physicians come forward independently.7 These beliefs and concurrent policies can propagate harmful, inaccurate biases against physicians who live with mental illness. These biases are compounded by the structural racism endemic in healthcare and academic medicine.8 Dehumanization in medicine adds fuel to this fire, projecting the ideal physician persona as an invulnerable, infallible superhuman who can witness intense suffering and work inhumane hours without impact upon the their mental health and well-being. Altogether, these factors increase fear and discourage help-seeking among physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure), ultimately harming physicians and patients in the process.9 Given that the FFD process involves evaluation, treatment, surveillance, and restrictions for individuals with stigmatized health conditions, these processes risk amplifying the impacts of trauma, racism, and oppression unless specifically designed to be antiracist, anti-oppressive, and trauma-informed.

TRAUMA-INFORMED APPROACH TO FFD

To encourage physician help-seeking, especially for stigmatized conditions, we must dismantle systems that traumatize physicians with mental illness (Appendix Figure) and build systems that invite and support courageous vulnerability and help-seeking.5,6 Institutions can provide evaluation and oversight of physicians while also adopting trauma-informed care principles. A trauma-informed approach to FFD would ask: How can we create systems that are informed by a genuine understanding of suffering to promote healing and avoid re-traumatization? Trauma-informed care emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, transparency, cultural humility (an antiracist, anti-oppression framework), collaboration, peer support, and patient empowerment.10 FFD evaluations differ by institution and by state, with some being performed internally and others utilizing external state physician health programs. We believe our recommendations below apply independent of context (Table).

NECESSARY CHANGES

Institutional Changes

All institutions must publish a detailed description of the FFD process, including its purpose, the definition of impairment or potential impairment, and the steps of the FFD evaluation. The FFD evaluation should be as limited in scope as possible, without invasive inquiry about the physician’s life-long history. Physicians should be invited to include a peer-support person throughout the entire process. The FFD “return to work agreement” should incorporate meaningful input from the physician as the expert in their own experience and, if already in treatment, informed by their healthcare providers. Given the stigmatization of mental health conditions and inherent power differentials in FFD processes, it is paramount that committees be diverse (including but not limited to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and mental illness) and comprised of physicians trained in trauma-informed processes who treat the conditions affecting the individual undergoing the FFD evaluation. Finally, trustworthiness requires accountability: We recommend that all FFD systems establish an external oversight body that is equipped to effect change in real time if a physician reports a potential process violation and that collects anonymous feedback from physicians to inform required continuous quality improvement.

State and Federal Changes

It is difficult to effect meaningful change without accurate measurement of physician suicide. Therefore, we recommend mandatory reporting of physician suicide and suspected suicide to publicly available, de-identified state registries. We call for each state medical licensing board to limit licensing questions to current impairment due to mental illness, substance use disorders, or other health condition, as recommended by the Federation of State Medical Boards.4 There is a critical need for federal legislation to fund improvements in workplace safety and enhanced access to mental health treatment on demand for physicians.

Especially in these extraordinary times, as physicians are being exposed to such high burdens of stress, suffering, loss, and moral injury, we must de-stigmatize mental illness, encourage help-seeking, and provide physicians struggling with mental illness with timely and compassionate support. By creating systems that are healing and supportive for physicians, we enhance healing for all.

Bipolar is my sun and my storm. As a physician, I am not ashamed of that. For my own health and that of my patients, I must work in a system where it is safe to come forward when I am struggling.

As I fought against what I felt was a toxic and injurious process, I was fortunate to not stand alone. More than 600 residents from 18 departments at my institution signed a petition in support of reforming the FFD process informed by my experience. My institution is in the early stages of responding to this display of strength and unity with a diverse taskforce dedicated to improving the Physician Well-being Committee and FFD process.

As I accompany my patients on their healing journeys, my own experience with recovery allows me to hold the hope of healing for them. My family, friends, mentors, and providers held these rays of hope for me when I was lost in my own darkness. I now know that being cured from disease is just one form of healing. My proximity to death grounds me as some of my patients approach the end of life. Notably, some of my primary care patients have read my story online and come to their appointments to tell me that they are proud to have me as their doctor, “bipolar and all.”

1. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373-2383 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

2. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA, Goeders LE, Satele DV, Shanafelt TD. Medical Licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(10):1486-1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.020

3. Hendin H, Reynolds C, Fox D, et al. Licensing and physician mental health: problems and possibilities. J Med Licens Discip. 2007;93(2):6-11.

4. Federation of State Medical Boards. Physician wellness and burnout: report and recommendations of the workgroup on physician wellness and burnout. 2018. Accessed February 6, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and-burnout.pdf

5. Kirch D. Physician mental health: my personal journey and professional plea. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):618-620. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003942

6. Cho HL, Huang CJ. Why mental health–related stigma matters for physician wellbeing, burnout, and patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;24:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05173-6

7. Hill AB. Breaking the stigma - a physician’s perspective on self-care and recovery. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1103-1105. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1615974

8. Grubbs V. Diversity, equity, and inclusion that matter. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):e25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMpv2022639

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.292

10. Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. Center for Healthcare Strategy. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/

1. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373-2383 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

2. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA, Goeders LE, Satele DV, Shanafelt TD. Medical Licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(10):1486-1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.020

3. Hendin H, Reynolds C, Fox D, et al. Licensing and physician mental health: problems and possibilities. J Med Licens Discip. 2007;93(2):6-11.

4. Federation of State Medical Boards. Physician wellness and burnout: report and recommendations of the workgroup on physician wellness and burnout. 2018. Accessed February 6, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and-burnout.pdf

5. Kirch D. Physician mental health: my personal journey and professional plea. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):618-620. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003942

6. Cho HL, Huang CJ. Why mental health–related stigma matters for physician wellbeing, burnout, and patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;24:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05173-6

7. Hill AB. Breaking the stigma - a physician’s perspective on self-care and recovery. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1103-1105. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1615974

8. Grubbs V. Diversity, equity, and inclusion that matter. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):e25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMpv2022639

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.292

10. Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. Center for Healthcare Strategy. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine