User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

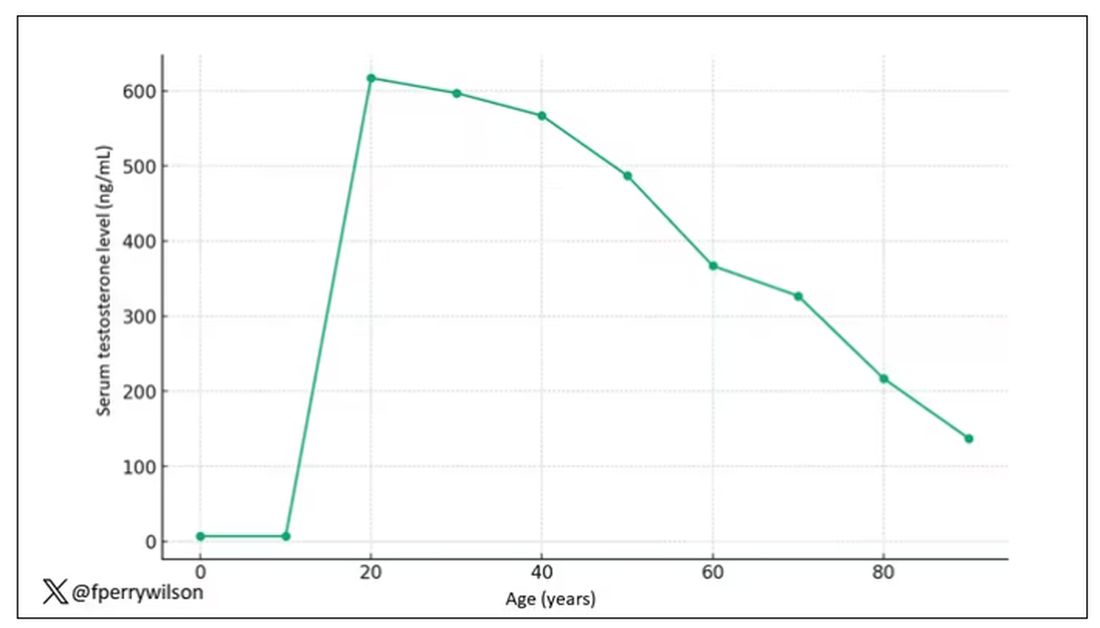

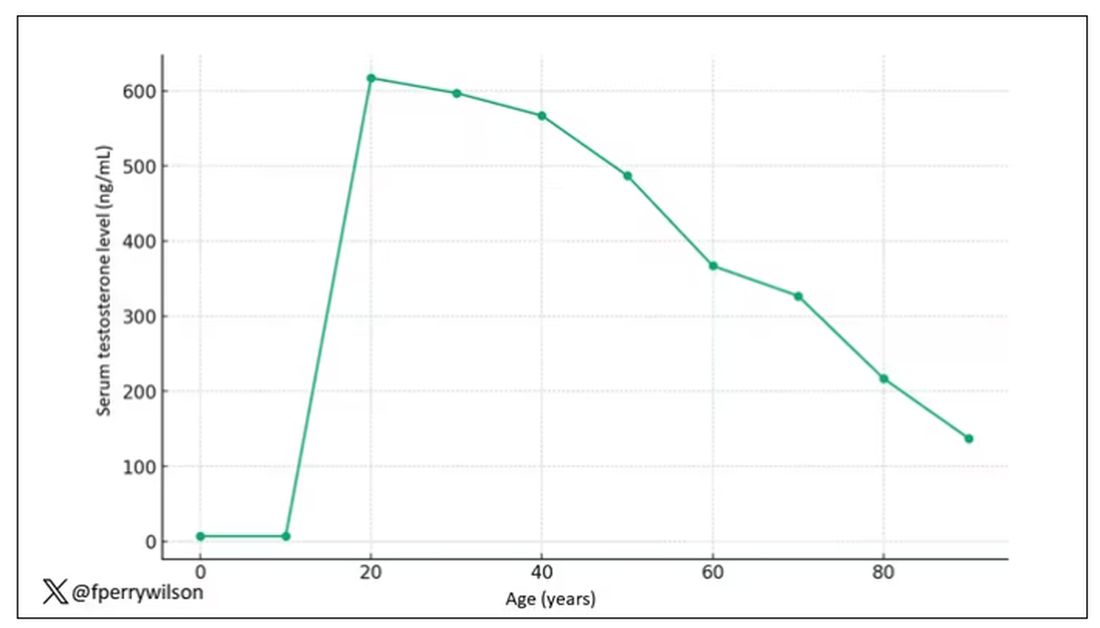

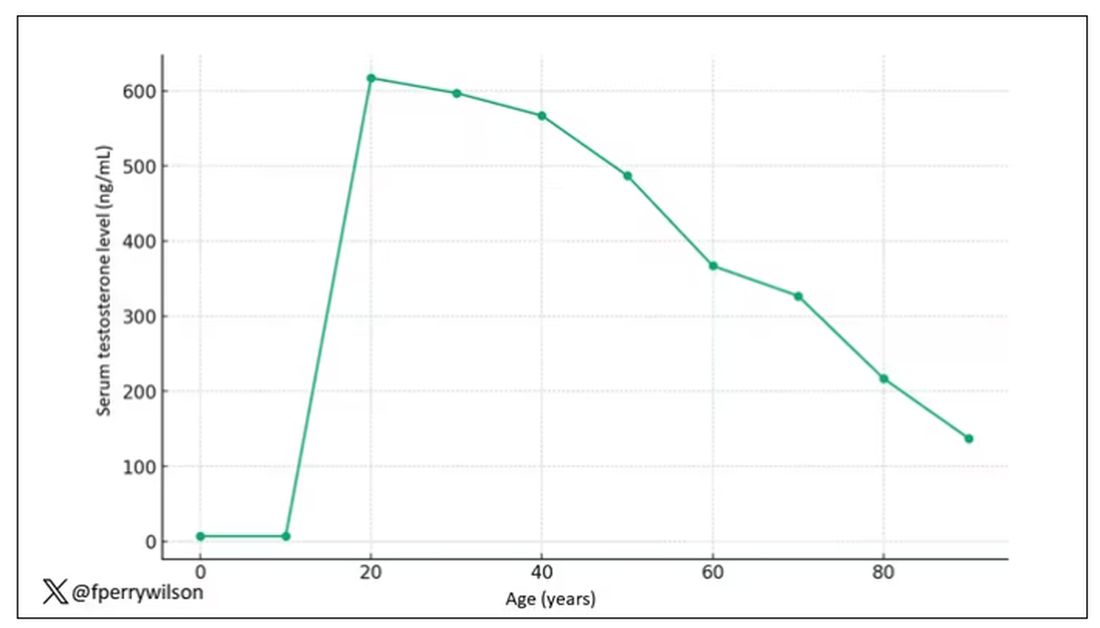

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

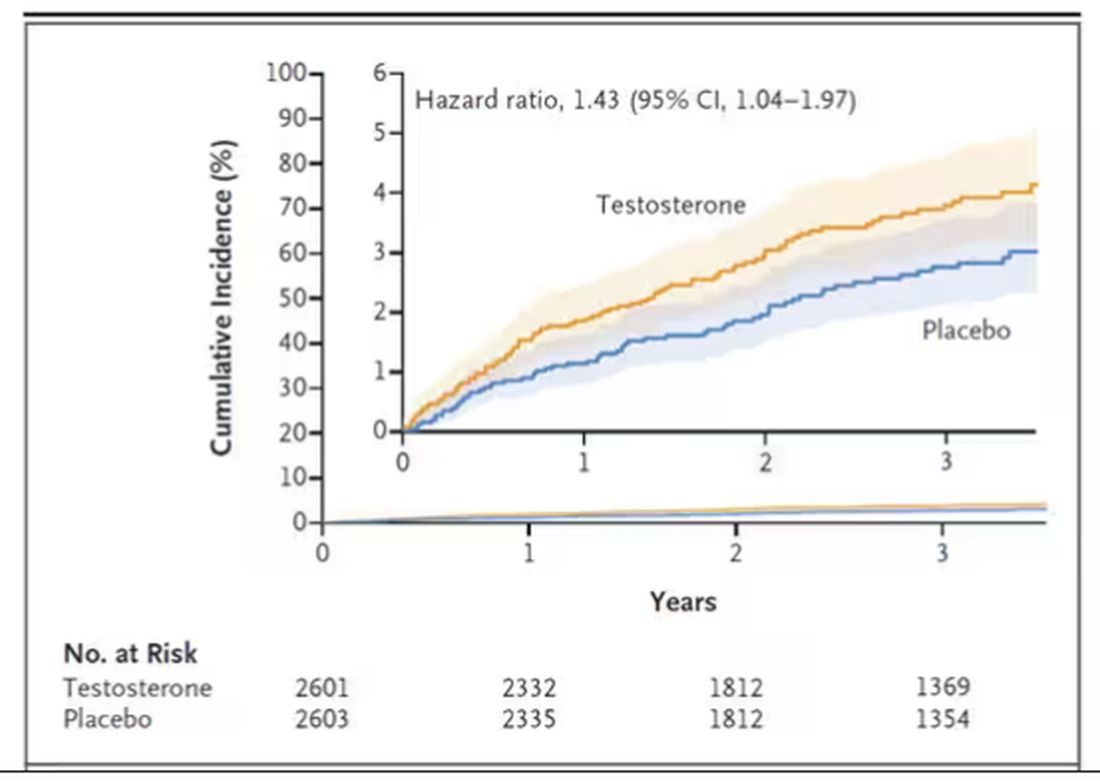

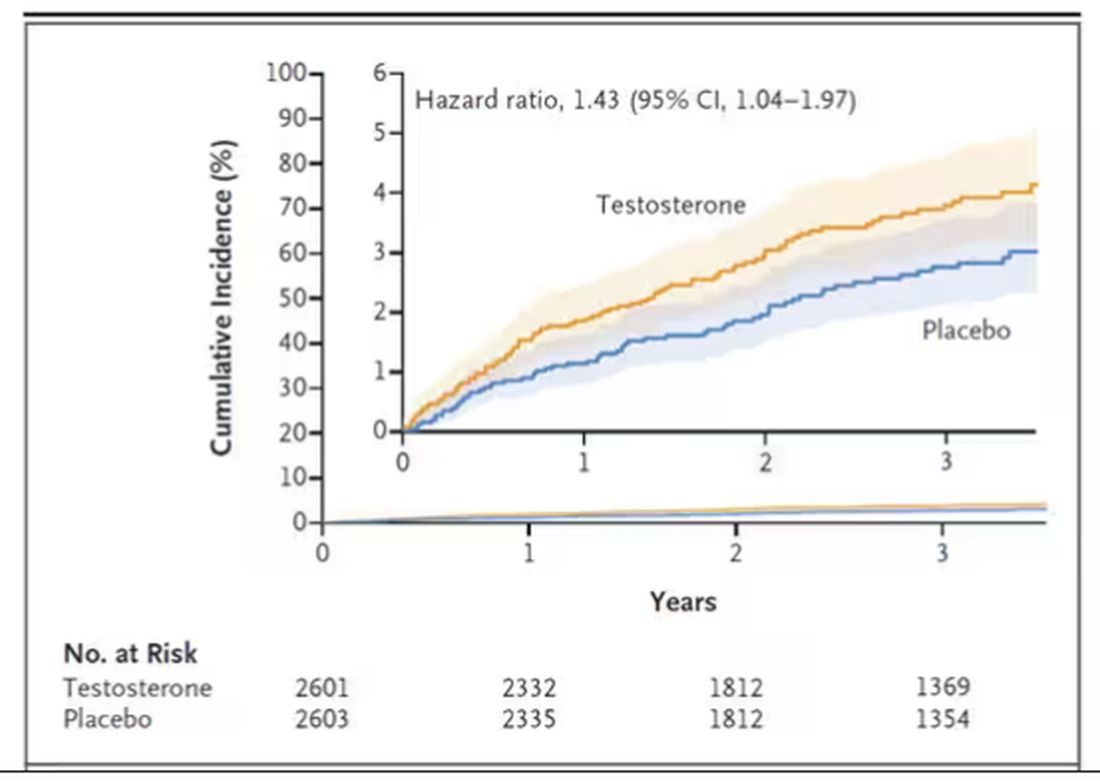

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

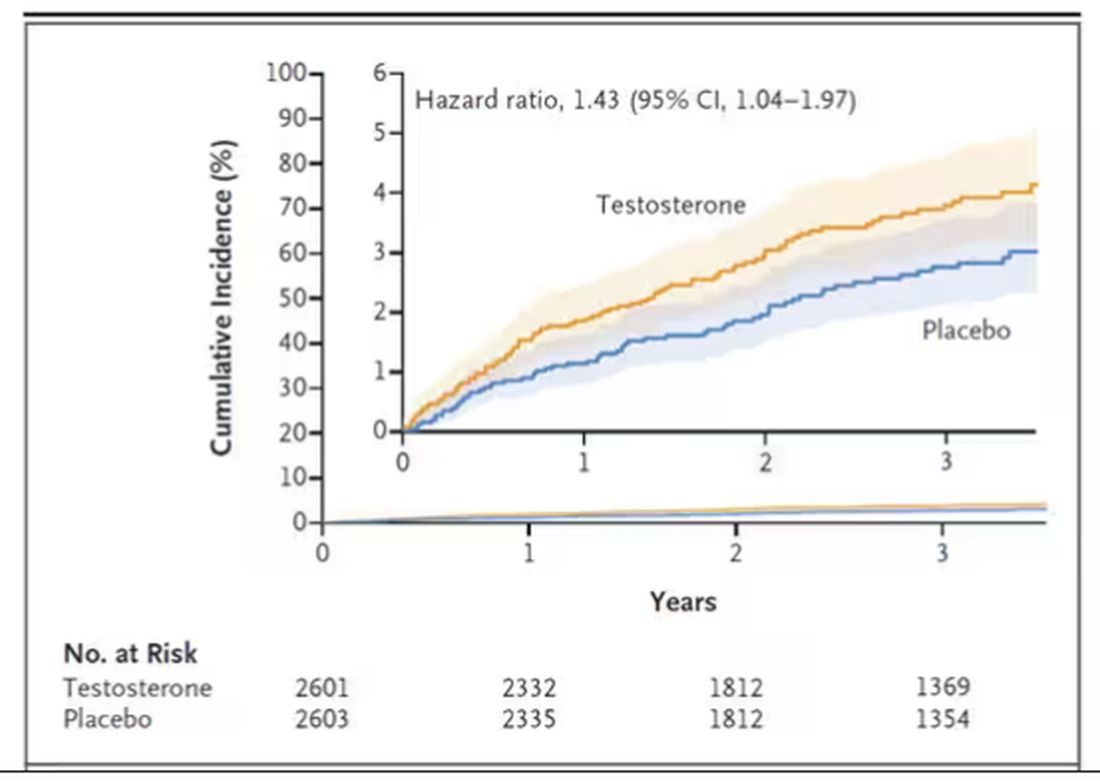

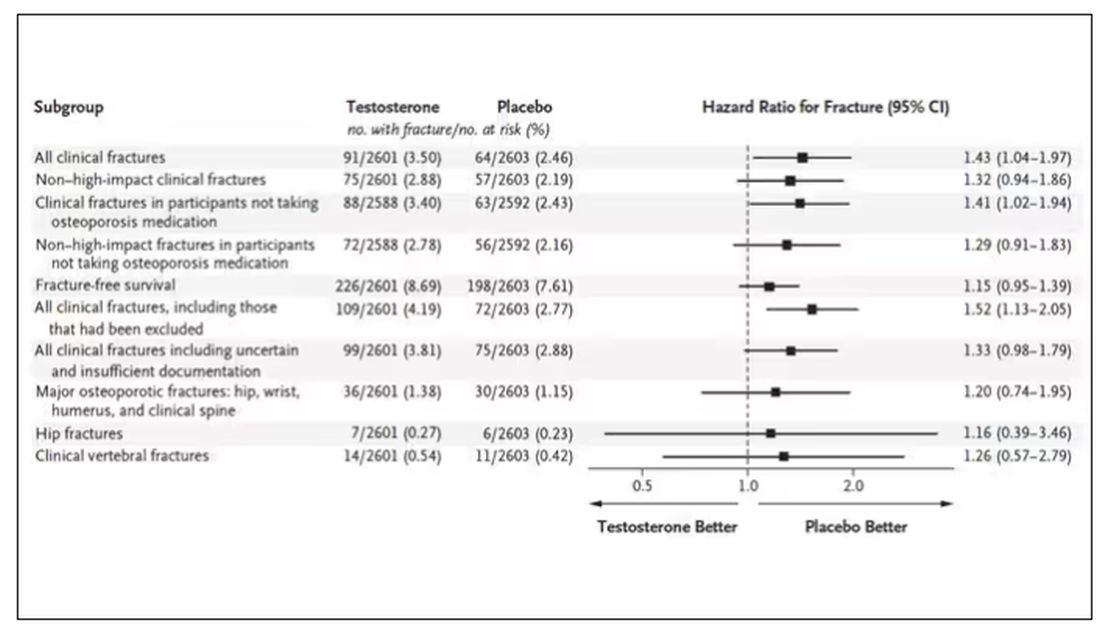

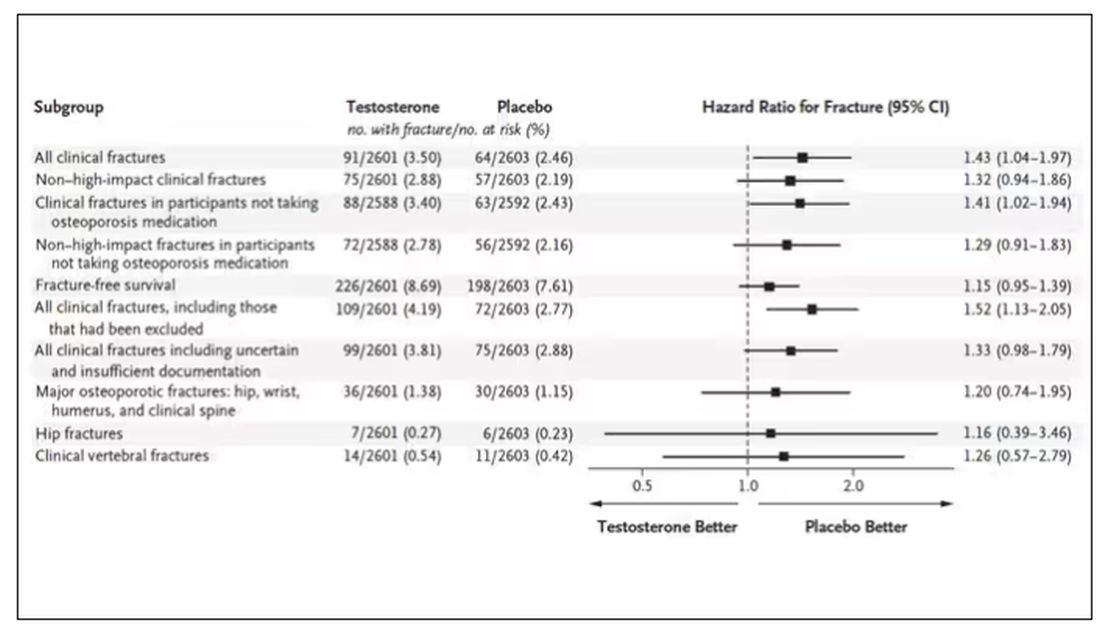

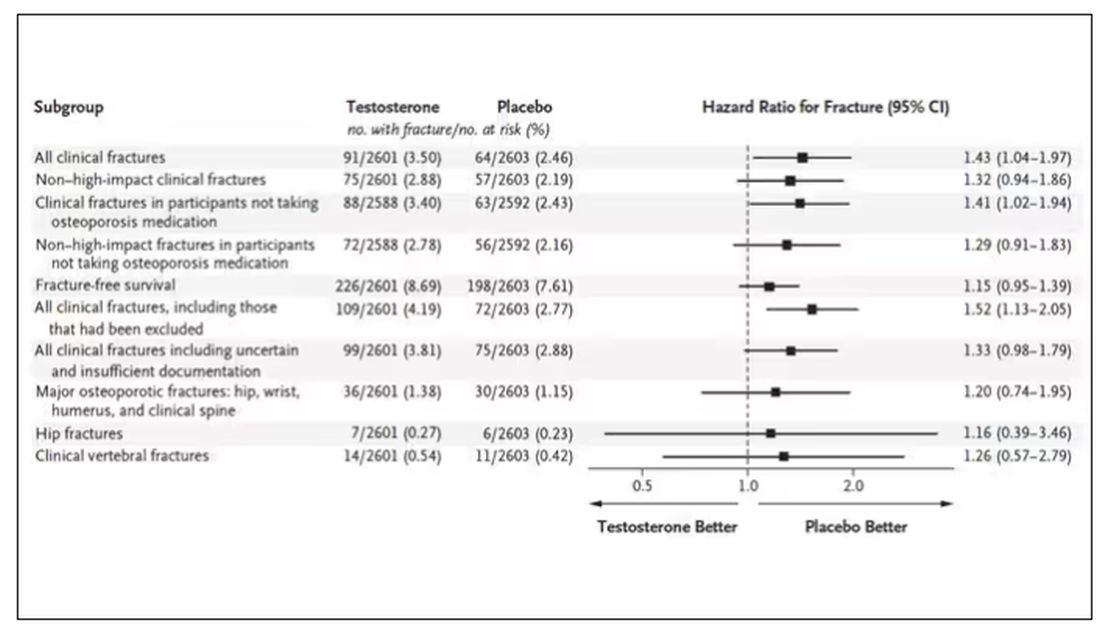

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.