User login

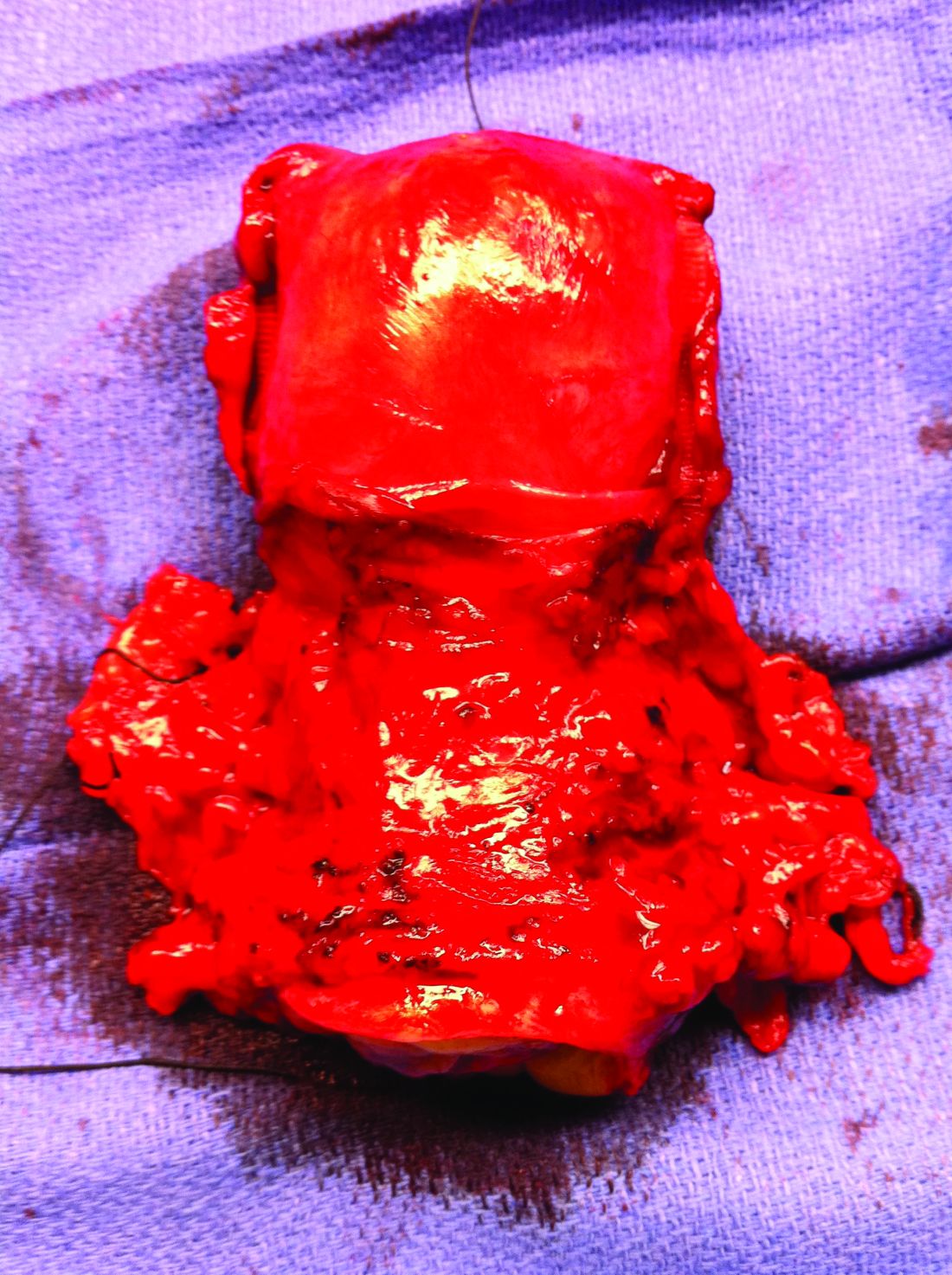

It has been more than 120 years since Ernst Wertheim, a Viennese surgeon, performed and described what is considered to have been the first radical total hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, yet this morbid procedure remains the standard of care for most early-stage cervical cancers. The rationale for this procedure, which included removal of the parametrial tissue, uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, and upper vagina en bloc with the cervix and uterus, was to obtain margins around a cancer that has a dominant radial growth pattern. The morbidity associated with this procedure is substantial. The parametrium houses important vascular, neural, and urologic structures. Unlike extrafascial hysterectomy, often referred to as “simple” hysterectomy, in which surgeons follow a fascial plane, and therefore a relatively avascular dissection, surgeons performing radical hysterectomy must venture outside of these embryologic fusion planes into less well–defined anatomy. Therefore, surgical complications are relatively common including hemorrhage, ureteral and bladder injury, as well as late-onset devastating complications such as fistula, urinary retention, or incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.1 More recently, variations of the Wertheim-Meigs radical hysterectomy have been described, and objective classifications created, which include modified radical procedures (removing less parametria) and nerve-sparing procedures to facilitate standardized nomenclature for tailoring the most appropriate procedure for any given tumor.2

The trend, and a positive one at that, over the course of the past century, has been a move away from routine radical surgical procedures for most clinical stage 1 cancers. No better example exists than breast cancer, in which the Halsted radical mastectomy has been largely replaced by less morbid breast-conserving or nonradical procedures with adjunct medical and radiation therapies offered to achieve high rates of cure with far more acceptable patient-centered outcomes.3 And so why is it that radical hysterectomy is still considered the standard of care for all but the smallest of microscopic cervical cancers?

The risk of lymph node metastases or recurrence is exceptionally low for women with microscopic (stage IA1) cervical cancers that are less than 3 mm in depth. Therefore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend nonradical surgical remedies (such as extrafascial hysterectomy, or cone biopsy or trachelectomy if fertility preservation is desired) for this earlier stage of disease.4 If there is lymphovascular space invasion (an indicator of poor prognosis and potential lymphatic involvement), a lymphadenectomy or sentinel lymph node biopsy is also recommended. For women with stage IA2 or IB lesions, radical excisions (either trachelectomy or hysterectomy) are considered the standard of care. However, this “gold standard” was achieved largely through legacy, and not a result of randomized trials comparing its outcomes with nonradical procedures.

Initial strides away from radical cervical cancer surgery focused on the goal of fertility preservation via radical trachelectomy which allowed women to preserve an intact uterine fundus. This was initially met with skepticism and concern that surgeons could be sacrificing oncologic outcomes in order to preserve a woman’s fertility. Thanks to pioneering work, including prospective research studies by surgeon innovators it has been shown that, in appropriately selected candidates with tumors less than 2 cm, it is an accepted standard of care.4 Radical vaginal or abdominal trachelectomy is associated with cancer recurrence rates of less than 5% and successful pregnancy in approximately three-quarters of patients in whom this is desired.5,6 However, full-term pregnancy is achieved in 50%-75% of cases, reflecting increased obstetric risk, and radical trachelectomy still subjects patients to the morbidity of a radical parametrial resection, despite the fact that many of them will have no residual carcinoma in their final pathological specimens.

Therefore, can we be even more conservative in our surgery for these patients? Are simple hysterectomy or conization potentially adequate treatments for small (<2 cm) stage IA2 and IB1 lesions that have favorable histology (<10 mm stromal invasion, low-risk histology, no lymphovascular space involvement, negative margins on conization and no lymph node metastases)? In patients whose tumor exhibits these histologic features, the likelihood of parametrial involvement is approximately 1%, calling into question the virtue of parametrial resection.7 Observational studies have identified mixed results on the safety of conservative surgical techniques in early-stage cervical cancer. In a study of the National Cancer Database, the outcomes of 2,543 radical hysterectomies and 1,388 extrafascial hysterectomies for women with stage IB1 disease were evaluated and observed a difference in 5-year survival (92.4% vs. 95.3%) favoring the radical procedure.8 Unfortunately, database analyses such as these are limited by potential confounders and discordance between the groups such as rates of lymphadenectomy, known involvement of oncologic surgeon specialists, and margin status. An alternative evaluation of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database including 2,571 patients with stage IB1 disease, all of whom had lymphadenectomy performed, showed no difference in 10-year disease-specific survival between the two surgical approaches.9

Ultimately, whether conservative procedures (such as conization or extrafascial hysterectomy) can be offered to women with small, low-risk IB1 or IA2 cervical cancers will be best determined by prospective single-arm or randomized trials. Fortunately, these are underway. Preliminary results from the ConCerv trial in which 100 women with early-stage, low-risk stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer were treated with either repeat conization or extrafascial hysterectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy showed acceptably low rates of recurrence (3%) with this approach.10 If the mature data supports this finding, it seems that, for appropriately selected and well-counseled patients, conservative surgery may become more broadly accepted as a reasonable option for treatment that spares women not only loss of fertility, but also the early and late surgical morbidity from radical procedures.

In the meantime, until more is known about the oncologic safety of nonradical procedures for stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer, this option should not be considered standard of care, and only offered to patients with favorable tumor factors who are well counseled regarding the uncertainty of this approach. It is critical that patients with early-stage cervical cancer be evaluated by a gynecologic cancer specialist prior to definitive surgical treatment as they are best equipped to evaluate risk profiles and counsel about her options for surgery, its known and unknown consequences, and the appropriateness of fertility preservation or radicality of surgery. We eagerly await the results of trials evaluating the safety of conservative cervical cancer surgery, which promise to advance us from 19th-century practices, preserving not only fertility, but also quality of life.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures and can be contacted at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Trimbos JB et al. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(3):375-8.

2. Querleu D and Morrow CP. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297-303.

3. Sakorafas GH and Safioleas M. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010 Mar;19(2):145-66.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cervical Cancer (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf. Accessed 2021 Apr 21.

5. Plante M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:290-7.

6. Wethington SL et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1251-7.

7. Domgue J and Schmeler K. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019 Feb;55:79-92.

8. Sia TY et al. Obstet Gyenecol. 2019;134(6):1132.

9. Tseng J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):44.

10. Schmeler K et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:A14-5.

It has been more than 120 years since Ernst Wertheim, a Viennese surgeon, performed and described what is considered to have been the first radical total hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, yet this morbid procedure remains the standard of care for most early-stage cervical cancers. The rationale for this procedure, which included removal of the parametrial tissue, uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, and upper vagina en bloc with the cervix and uterus, was to obtain margins around a cancer that has a dominant radial growth pattern. The morbidity associated with this procedure is substantial. The parametrium houses important vascular, neural, and urologic structures. Unlike extrafascial hysterectomy, often referred to as “simple” hysterectomy, in which surgeons follow a fascial plane, and therefore a relatively avascular dissection, surgeons performing radical hysterectomy must venture outside of these embryologic fusion planes into less well–defined anatomy. Therefore, surgical complications are relatively common including hemorrhage, ureteral and bladder injury, as well as late-onset devastating complications such as fistula, urinary retention, or incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.1 More recently, variations of the Wertheim-Meigs radical hysterectomy have been described, and objective classifications created, which include modified radical procedures (removing less parametria) and nerve-sparing procedures to facilitate standardized nomenclature for tailoring the most appropriate procedure for any given tumor.2

The trend, and a positive one at that, over the course of the past century, has been a move away from routine radical surgical procedures for most clinical stage 1 cancers. No better example exists than breast cancer, in which the Halsted radical mastectomy has been largely replaced by less morbid breast-conserving or nonradical procedures with adjunct medical and radiation therapies offered to achieve high rates of cure with far more acceptable patient-centered outcomes.3 And so why is it that radical hysterectomy is still considered the standard of care for all but the smallest of microscopic cervical cancers?

The risk of lymph node metastases or recurrence is exceptionally low for women with microscopic (stage IA1) cervical cancers that are less than 3 mm in depth. Therefore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend nonradical surgical remedies (such as extrafascial hysterectomy, or cone biopsy or trachelectomy if fertility preservation is desired) for this earlier stage of disease.4 If there is lymphovascular space invasion (an indicator of poor prognosis and potential lymphatic involvement), a lymphadenectomy or sentinel lymph node biopsy is also recommended. For women with stage IA2 or IB lesions, radical excisions (either trachelectomy or hysterectomy) are considered the standard of care. However, this “gold standard” was achieved largely through legacy, and not a result of randomized trials comparing its outcomes with nonradical procedures.

Initial strides away from radical cervical cancer surgery focused on the goal of fertility preservation via radical trachelectomy which allowed women to preserve an intact uterine fundus. This was initially met with skepticism and concern that surgeons could be sacrificing oncologic outcomes in order to preserve a woman’s fertility. Thanks to pioneering work, including prospective research studies by surgeon innovators it has been shown that, in appropriately selected candidates with tumors less than 2 cm, it is an accepted standard of care.4 Radical vaginal or abdominal trachelectomy is associated with cancer recurrence rates of less than 5% and successful pregnancy in approximately three-quarters of patients in whom this is desired.5,6 However, full-term pregnancy is achieved in 50%-75% of cases, reflecting increased obstetric risk, and radical trachelectomy still subjects patients to the morbidity of a radical parametrial resection, despite the fact that many of them will have no residual carcinoma in their final pathological specimens.

Therefore, can we be even more conservative in our surgery for these patients? Are simple hysterectomy or conization potentially adequate treatments for small (<2 cm) stage IA2 and IB1 lesions that have favorable histology (<10 mm stromal invasion, low-risk histology, no lymphovascular space involvement, negative margins on conization and no lymph node metastases)? In patients whose tumor exhibits these histologic features, the likelihood of parametrial involvement is approximately 1%, calling into question the virtue of parametrial resection.7 Observational studies have identified mixed results on the safety of conservative surgical techniques in early-stage cervical cancer. In a study of the National Cancer Database, the outcomes of 2,543 radical hysterectomies and 1,388 extrafascial hysterectomies for women with stage IB1 disease were evaluated and observed a difference in 5-year survival (92.4% vs. 95.3%) favoring the radical procedure.8 Unfortunately, database analyses such as these are limited by potential confounders and discordance between the groups such as rates of lymphadenectomy, known involvement of oncologic surgeon specialists, and margin status. An alternative evaluation of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database including 2,571 patients with stage IB1 disease, all of whom had lymphadenectomy performed, showed no difference in 10-year disease-specific survival between the two surgical approaches.9

Ultimately, whether conservative procedures (such as conization or extrafascial hysterectomy) can be offered to women with small, low-risk IB1 or IA2 cervical cancers will be best determined by prospective single-arm or randomized trials. Fortunately, these are underway. Preliminary results from the ConCerv trial in which 100 women with early-stage, low-risk stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer were treated with either repeat conization or extrafascial hysterectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy showed acceptably low rates of recurrence (3%) with this approach.10 If the mature data supports this finding, it seems that, for appropriately selected and well-counseled patients, conservative surgery may become more broadly accepted as a reasonable option for treatment that spares women not only loss of fertility, but also the early and late surgical morbidity from radical procedures.

In the meantime, until more is known about the oncologic safety of nonradical procedures for stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer, this option should not be considered standard of care, and only offered to patients with favorable tumor factors who are well counseled regarding the uncertainty of this approach. It is critical that patients with early-stage cervical cancer be evaluated by a gynecologic cancer specialist prior to definitive surgical treatment as they are best equipped to evaluate risk profiles and counsel about her options for surgery, its known and unknown consequences, and the appropriateness of fertility preservation or radicality of surgery. We eagerly await the results of trials evaluating the safety of conservative cervical cancer surgery, which promise to advance us from 19th-century practices, preserving not only fertility, but also quality of life.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures and can be contacted at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Trimbos JB et al. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(3):375-8.

2. Querleu D and Morrow CP. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297-303.

3. Sakorafas GH and Safioleas M. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010 Mar;19(2):145-66.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cervical Cancer (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf. Accessed 2021 Apr 21.

5. Plante M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:290-7.

6. Wethington SL et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1251-7.

7. Domgue J and Schmeler K. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019 Feb;55:79-92.

8. Sia TY et al. Obstet Gyenecol. 2019;134(6):1132.

9. Tseng J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):44.

10. Schmeler K et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:A14-5.

It has been more than 120 years since Ernst Wertheim, a Viennese surgeon, performed and described what is considered to have been the first radical total hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, yet this morbid procedure remains the standard of care for most early-stage cervical cancers. The rationale for this procedure, which included removal of the parametrial tissue, uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, and upper vagina en bloc with the cervix and uterus, was to obtain margins around a cancer that has a dominant radial growth pattern. The morbidity associated with this procedure is substantial. The parametrium houses important vascular, neural, and urologic structures. Unlike extrafascial hysterectomy, often referred to as “simple” hysterectomy, in which surgeons follow a fascial plane, and therefore a relatively avascular dissection, surgeons performing radical hysterectomy must venture outside of these embryologic fusion planes into less well–defined anatomy. Therefore, surgical complications are relatively common including hemorrhage, ureteral and bladder injury, as well as late-onset devastating complications such as fistula, urinary retention, or incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.1 More recently, variations of the Wertheim-Meigs radical hysterectomy have been described, and objective classifications created, which include modified radical procedures (removing less parametria) and nerve-sparing procedures to facilitate standardized nomenclature for tailoring the most appropriate procedure for any given tumor.2

The trend, and a positive one at that, over the course of the past century, has been a move away from routine radical surgical procedures for most clinical stage 1 cancers. No better example exists than breast cancer, in which the Halsted radical mastectomy has been largely replaced by less morbid breast-conserving or nonradical procedures with adjunct medical and radiation therapies offered to achieve high rates of cure with far more acceptable patient-centered outcomes.3 And so why is it that radical hysterectomy is still considered the standard of care for all but the smallest of microscopic cervical cancers?

The risk of lymph node metastases or recurrence is exceptionally low for women with microscopic (stage IA1) cervical cancers that are less than 3 mm in depth. Therefore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend nonradical surgical remedies (such as extrafascial hysterectomy, or cone biopsy or trachelectomy if fertility preservation is desired) for this earlier stage of disease.4 If there is lymphovascular space invasion (an indicator of poor prognosis and potential lymphatic involvement), a lymphadenectomy or sentinel lymph node biopsy is also recommended. For women with stage IA2 or IB lesions, radical excisions (either trachelectomy or hysterectomy) are considered the standard of care. However, this “gold standard” was achieved largely through legacy, and not a result of randomized trials comparing its outcomes with nonradical procedures.

Initial strides away from radical cervical cancer surgery focused on the goal of fertility preservation via radical trachelectomy which allowed women to preserve an intact uterine fundus. This was initially met with skepticism and concern that surgeons could be sacrificing oncologic outcomes in order to preserve a woman’s fertility. Thanks to pioneering work, including prospective research studies by surgeon innovators it has been shown that, in appropriately selected candidates with tumors less than 2 cm, it is an accepted standard of care.4 Radical vaginal or abdominal trachelectomy is associated with cancer recurrence rates of less than 5% and successful pregnancy in approximately three-quarters of patients in whom this is desired.5,6 However, full-term pregnancy is achieved in 50%-75% of cases, reflecting increased obstetric risk, and radical trachelectomy still subjects patients to the morbidity of a radical parametrial resection, despite the fact that many of them will have no residual carcinoma in their final pathological specimens.

Therefore, can we be even more conservative in our surgery for these patients? Are simple hysterectomy or conization potentially adequate treatments for small (<2 cm) stage IA2 and IB1 lesions that have favorable histology (<10 mm stromal invasion, low-risk histology, no lymphovascular space involvement, negative margins on conization and no lymph node metastases)? In patients whose tumor exhibits these histologic features, the likelihood of parametrial involvement is approximately 1%, calling into question the virtue of parametrial resection.7 Observational studies have identified mixed results on the safety of conservative surgical techniques in early-stage cervical cancer. In a study of the National Cancer Database, the outcomes of 2,543 radical hysterectomies and 1,388 extrafascial hysterectomies for women with stage IB1 disease were evaluated and observed a difference in 5-year survival (92.4% vs. 95.3%) favoring the radical procedure.8 Unfortunately, database analyses such as these are limited by potential confounders and discordance between the groups such as rates of lymphadenectomy, known involvement of oncologic surgeon specialists, and margin status. An alternative evaluation of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database including 2,571 patients with stage IB1 disease, all of whom had lymphadenectomy performed, showed no difference in 10-year disease-specific survival between the two surgical approaches.9

Ultimately, whether conservative procedures (such as conization or extrafascial hysterectomy) can be offered to women with small, low-risk IB1 or IA2 cervical cancers will be best determined by prospective single-arm or randomized trials. Fortunately, these are underway. Preliminary results from the ConCerv trial in which 100 women with early-stage, low-risk stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer were treated with either repeat conization or extrafascial hysterectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy showed acceptably low rates of recurrence (3%) with this approach.10 If the mature data supports this finding, it seems that, for appropriately selected and well-counseled patients, conservative surgery may become more broadly accepted as a reasonable option for treatment that spares women not only loss of fertility, but also the early and late surgical morbidity from radical procedures.

In the meantime, until more is known about the oncologic safety of nonradical procedures for stage IA2 and IB1 cervical cancer, this option should not be considered standard of care, and only offered to patients with favorable tumor factors who are well counseled regarding the uncertainty of this approach. It is critical that patients with early-stage cervical cancer be evaluated by a gynecologic cancer specialist prior to definitive surgical treatment as they are best equipped to evaluate risk profiles and counsel about her options for surgery, its known and unknown consequences, and the appropriateness of fertility preservation or radicality of surgery. We eagerly await the results of trials evaluating the safety of conservative cervical cancer surgery, which promise to advance us from 19th-century practices, preserving not only fertility, but also quality of life.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures and can be contacted at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Trimbos JB et al. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(3):375-8.

2. Querleu D and Morrow CP. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297-303.

3. Sakorafas GH and Safioleas M. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010 Mar;19(2):145-66.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cervical Cancer (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf. Accessed 2021 Apr 21.

5. Plante M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:290-7.

6. Wethington SL et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1251-7.

7. Domgue J and Schmeler K. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019 Feb;55:79-92.

8. Sia TY et al. Obstet Gyenecol. 2019;134(6):1132.

9. Tseng J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):44.

10. Schmeler K et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:A14-5.