User login

It’s “summertime and the livin’ is easy” according to the lyric from an old George Gershwin song. But sometimes, summer activities can lead to illnesses that can disrupt a child’s easy living.

Case: An otherwise healthy 11-year-old presents with four to five loose stools per day, mild nausea, excess flatulence, and cramps for 12 days with a 5-pound weight loss. His loose-to-mushy stools have no blood or mucous but smell worse than usual. He has had no fever, vomiting, rashes, or joint symptoms. A month ago, he went hiking/camping on the Appalachian Trail, drank boiled stream water. and slept in a common-use semi-enclosed shelter. He waded through streams and shared “Trail Magic” (soft drinks being cooled in a fresh mountain stream). Two other campers report similar symptoms.

Differential diagnosis: Broadly, we should consider bacteria, viruses, and parasites. But generally, bacteria are likely to produce more systemic symptoms and usually do not last 12 days. That said, this could be Clostridioides difficile, yet that seems unlikely because he is otherwise healthy and has no apparent risk factors. Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and some Escherichia coli infections may drag on for more than a week but the lack of systemic symptoms or blood/mucous lowers the likelihood. Viral agents (rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, astrovirus, calicivirus, or sapovirus) seem unlikely because of the long symptom duration and the child’s preteen age.

The history and presentation seem more likely attributable to a parasite. Uncommonly detected protozoa include Microsporidium (mostly Enterocytozoon bieneusi) and amoeba. Microsporidium is very rare and seen mostly in immune compromised hosts, for example, those living with HIV. Amebiasis occurs mostly after travel to endemic areas, and stools usually contain blood or mucous. Some roundworm or tapeworm infestations cause abdominal pain and abnormal stools, but the usual exposures are absent. Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis, and/or Cystoisospora belli best fit this presentation given his hiking/camping trip.

Workup. Laboratory testing of stool is warranted (because of weight loss and persistent diarrhea) despite a lack of systemic signs. Initially, bacterial culture, C. difficile testing, and viral testing seem unwarranted. The best initial approach, given our most likely suspects, is protozoan/parasite testing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends testing up to three stools collected on separate days.1 Initially, stool testing for giardia and cryptosporidium antigens by EIA assays could be done as a point-of-care test. Such antigen tests are often the first step because of their ease of use, relatively low expense, reasonably high sensitivity and specificity, and rapid turnaround (as little as 1 hour). Alternatively, direct examination of three stools for ova and parasites (O&P) and acid-fast stain or direct fluorescent antibody testing can usually detect our main suspects (giardia, cryptosporidium, cyclospora, and cystoisospora) along with other less likely parasites.

Some laboratories, however, use syndromic stool testing approaches (multiplex nucleic acid panels) that detect over 20 different bacteria, viruses, and select parasites. Multiplex testing has yielded increased detection rates, compared with microscopic examination alone in some settings. Further, they also share ease-of-use and rapid turnaround times with parasite antigen assays while requiring less hands-on time by laboratory personnel, compared with direct microscopic examination. However, multiplex assays are expensive and more readily detect commensal organisms, so they are not necessarily the ideal test in all diarrheal illnesses.

Diagnosis. You decide to first order giardia and cryptosporidium antigen testing because you are highly suspicious that giardia is the cause, based on wild-water exposure, the presentation, and symptom duration. You also order full microscopic O&P examination because you know that parasites can “run in packs.” Results of testing the first stool are positive for giardia. Microscopic examination on each of three stools is negative except for giardia trophozoites (the noninfectious form) in stools two and three.

Giardia overview. Giardia is the most common protozoan causing diarrhea in the United States, is fecal-oral spread, and like Shigella spp., is a low-inoculum infection (ingestion of as few as 10-100 cysts). Acquisition in the United States has been estimated as being 75% from contaminated water (streams are a classic source.2 Other sources are contaminated food (fresh produce is classic) and in some cases sexual encounters (mostly in men who have sex with men). Most detections are sporadic, but outbreaks can occur with case numbers usually below 20; 40% of outbreaks are attributable to contaminated water or food.3 Evaluating symptomatic household members can be important as transmission in families can occur.

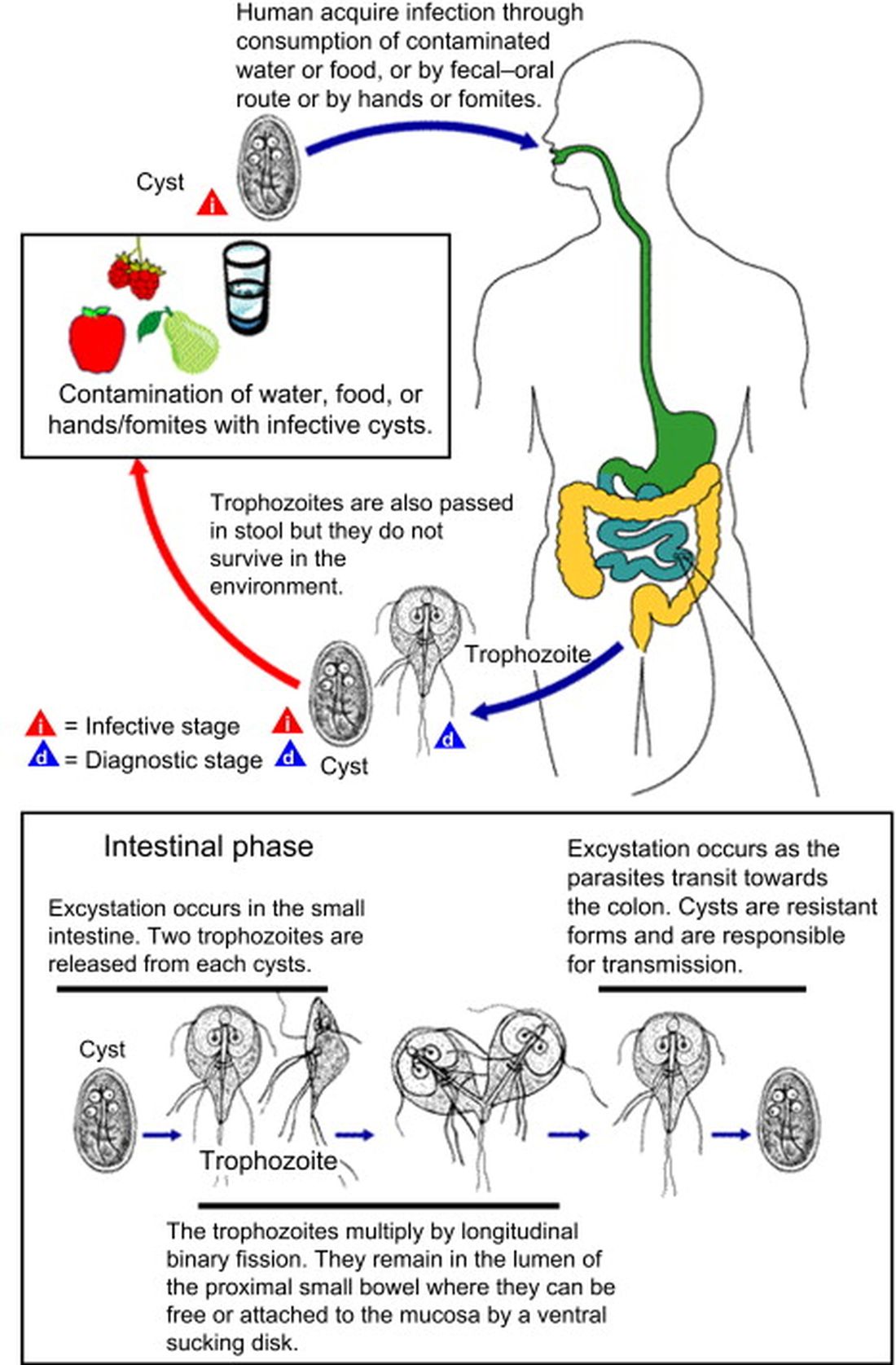

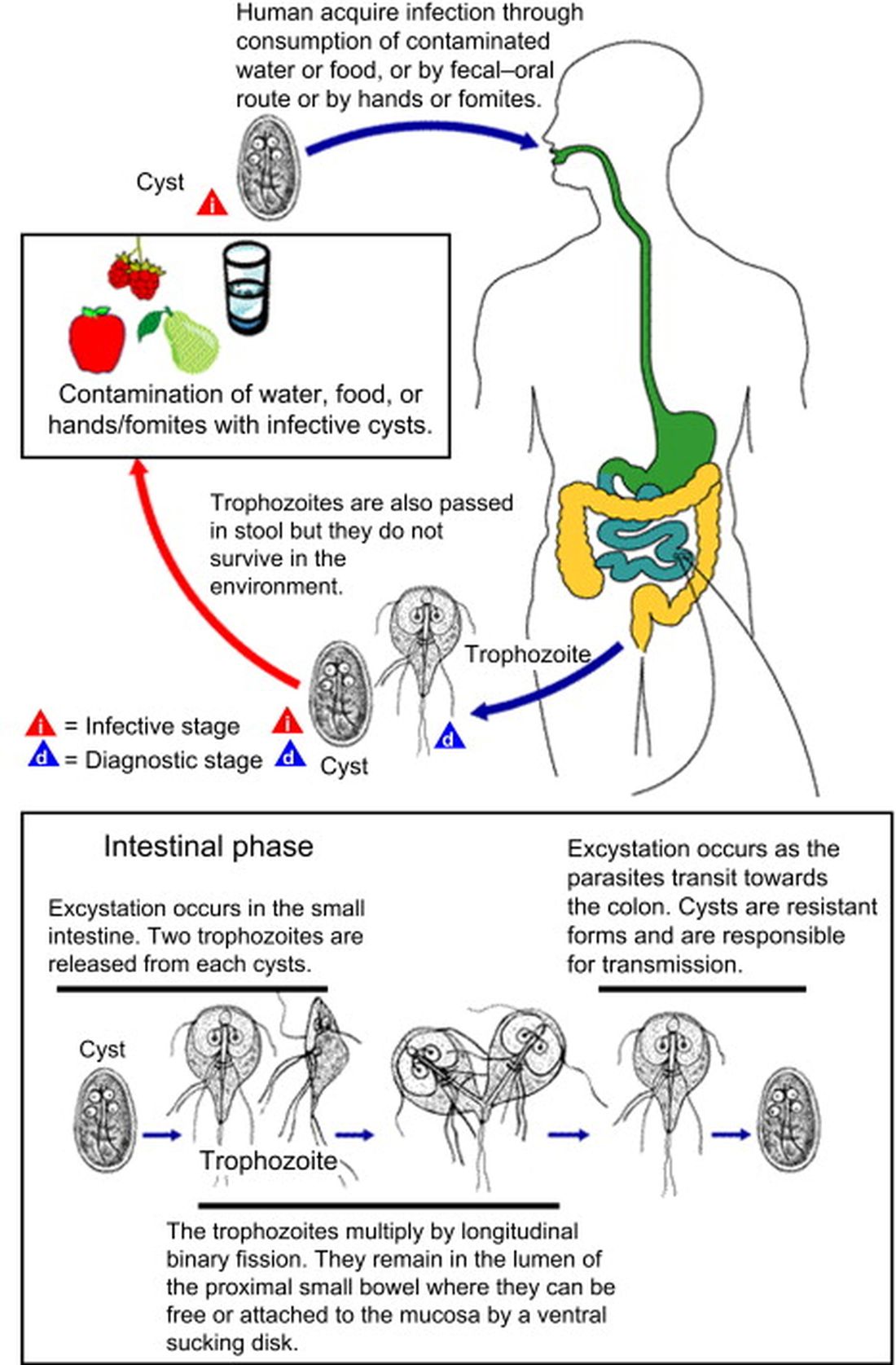

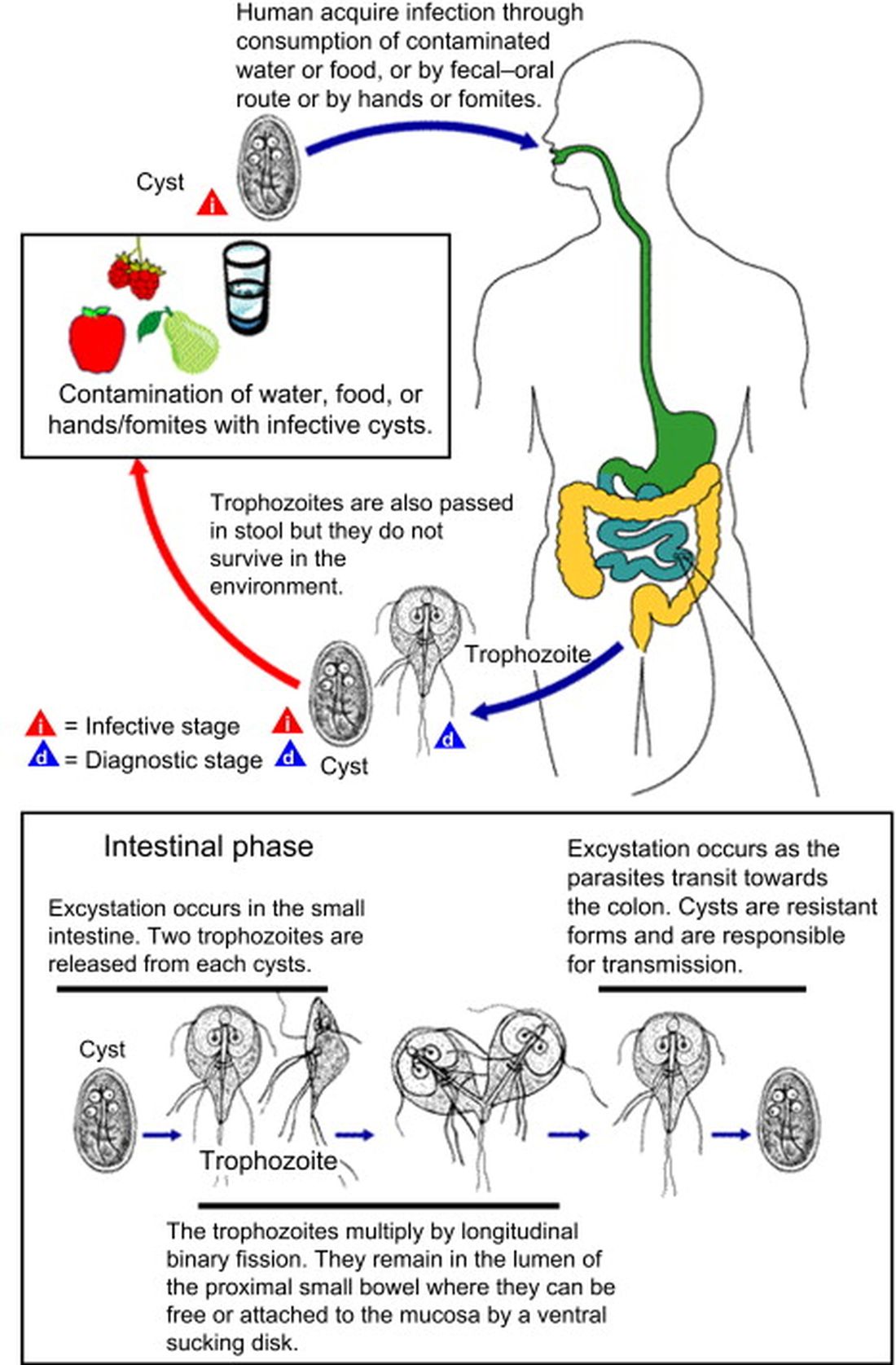

After ingestion, the cysts uncoat and form trophozoites, which reside mostly in the small bowel (Figure), causing inflammation and altering gut membrane permeability, thereby reducing nutrient absorption and circulating amino acids. Along with decreased food intake, altered absorption can lead to weight loss and potentially reduce growth in young children. Some trophozoites replicate while others encyst, eventually passing into stool. The cysts can survive for months in water or the environment (lakes, swimming pools, and clear mountain streams). Giardia has been linked to beavers’ feces contaminating wild-water sources, hence the moniker “Beaver fever” and warnings about stream water related to wilderness hiking.4

Management. Supportive therapy as with any diarrheal illness is the cornerstone of management. Specific antiparasitic treatment has traditionally been with metronidazole compounded into a liquid for young children, but the awful taste and frequent dosing often result in poor adherence. Nevertheless, published cure rates range from 80% to 100%. The taste issue, known adverse effects, and lack of FDA approval for giardia, have led to use of other drugs.5 One dose of tinidazole is as effective as metronidazole and can be prescribed for children 3 years old or older. But the drug nitazoxanide is becoming more standard. It is as effective as either alternative, and is FDA approved for children 1 year old and older. Nitazoxanide also is effective against other intestinal parasites (e.g., cryptosporidium). Nitazoxanide’s 3-day course involves every-12-hour dosing with food with each dose being 5 mL (100 mg) for 1- to 3-year-olds, 10 mL (200 mg) for 4- to 11-year-olds, and one tablet (500 mg) or 25 mL (500 mg) for children 12 years old or older.6

Key elements in this subacute nonsystemic diarrheal presentation were primitive camping history, multiple stream water contacts, nearly 2 weeks of symptoms, weight loss, and flatulence/cramping, but no fever or stool blood/mucous. Two friends also appear to be similarly symptomatic, so a common exposure seemed likely This is typical for several summertime activity–related parasites. So,

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Diagnosis and Treatment Information for Medical Professionals, Giardia, Parasites. CDC.

2. Krumrie S et al. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2022;2:100084. doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2022.100084.

3. Baldursson S and Karanis P. Water Res. 2011 Dec 15. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.013.

4. “Water on the Appalachian Trail” AppalachianTrail.com.

5. Giardiasis: Treatment and prevention. UpToDate.

6. Kimberlin D et al. Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021. 32nd ed.) Giardia duodenalis infections. pp. 335-8; and p. 961 (Table 4.11).

It’s “summertime and the livin’ is easy” according to the lyric from an old George Gershwin song. But sometimes, summer activities can lead to illnesses that can disrupt a child’s easy living.

Case: An otherwise healthy 11-year-old presents with four to five loose stools per day, mild nausea, excess flatulence, and cramps for 12 days with a 5-pound weight loss. His loose-to-mushy stools have no blood or mucous but smell worse than usual. He has had no fever, vomiting, rashes, or joint symptoms. A month ago, he went hiking/camping on the Appalachian Trail, drank boiled stream water. and slept in a common-use semi-enclosed shelter. He waded through streams and shared “Trail Magic” (soft drinks being cooled in a fresh mountain stream). Two other campers report similar symptoms.

Differential diagnosis: Broadly, we should consider bacteria, viruses, and parasites. But generally, bacteria are likely to produce more systemic symptoms and usually do not last 12 days. That said, this could be Clostridioides difficile, yet that seems unlikely because he is otherwise healthy and has no apparent risk factors. Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and some Escherichia coli infections may drag on for more than a week but the lack of systemic symptoms or blood/mucous lowers the likelihood. Viral agents (rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, astrovirus, calicivirus, or sapovirus) seem unlikely because of the long symptom duration and the child’s preteen age.

The history and presentation seem more likely attributable to a parasite. Uncommonly detected protozoa include Microsporidium (mostly Enterocytozoon bieneusi) and amoeba. Microsporidium is very rare and seen mostly in immune compromised hosts, for example, those living with HIV. Amebiasis occurs mostly after travel to endemic areas, and stools usually contain blood or mucous. Some roundworm or tapeworm infestations cause abdominal pain and abnormal stools, but the usual exposures are absent. Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis, and/or Cystoisospora belli best fit this presentation given his hiking/camping trip.

Workup. Laboratory testing of stool is warranted (because of weight loss and persistent diarrhea) despite a lack of systemic signs. Initially, bacterial culture, C. difficile testing, and viral testing seem unwarranted. The best initial approach, given our most likely suspects, is protozoan/parasite testing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends testing up to three stools collected on separate days.1 Initially, stool testing for giardia and cryptosporidium antigens by EIA assays could be done as a point-of-care test. Such antigen tests are often the first step because of their ease of use, relatively low expense, reasonably high sensitivity and specificity, and rapid turnaround (as little as 1 hour). Alternatively, direct examination of three stools for ova and parasites (O&P) and acid-fast stain or direct fluorescent antibody testing can usually detect our main suspects (giardia, cryptosporidium, cyclospora, and cystoisospora) along with other less likely parasites.

Some laboratories, however, use syndromic stool testing approaches (multiplex nucleic acid panels) that detect over 20 different bacteria, viruses, and select parasites. Multiplex testing has yielded increased detection rates, compared with microscopic examination alone in some settings. Further, they also share ease-of-use and rapid turnaround times with parasite antigen assays while requiring less hands-on time by laboratory personnel, compared with direct microscopic examination. However, multiplex assays are expensive and more readily detect commensal organisms, so they are not necessarily the ideal test in all diarrheal illnesses.

Diagnosis. You decide to first order giardia and cryptosporidium antigen testing because you are highly suspicious that giardia is the cause, based on wild-water exposure, the presentation, and symptom duration. You also order full microscopic O&P examination because you know that parasites can “run in packs.” Results of testing the first stool are positive for giardia. Microscopic examination on each of three stools is negative except for giardia trophozoites (the noninfectious form) in stools two and three.

Giardia overview. Giardia is the most common protozoan causing diarrhea in the United States, is fecal-oral spread, and like Shigella spp., is a low-inoculum infection (ingestion of as few as 10-100 cysts). Acquisition in the United States has been estimated as being 75% from contaminated water (streams are a classic source.2 Other sources are contaminated food (fresh produce is classic) and in some cases sexual encounters (mostly in men who have sex with men). Most detections are sporadic, but outbreaks can occur with case numbers usually below 20; 40% of outbreaks are attributable to contaminated water or food.3 Evaluating symptomatic household members can be important as transmission in families can occur.

After ingestion, the cysts uncoat and form trophozoites, which reside mostly in the small bowel (Figure), causing inflammation and altering gut membrane permeability, thereby reducing nutrient absorption and circulating amino acids. Along with decreased food intake, altered absorption can lead to weight loss and potentially reduce growth in young children. Some trophozoites replicate while others encyst, eventually passing into stool. The cysts can survive for months in water or the environment (lakes, swimming pools, and clear mountain streams). Giardia has been linked to beavers’ feces contaminating wild-water sources, hence the moniker “Beaver fever” and warnings about stream water related to wilderness hiking.4

Management. Supportive therapy as with any diarrheal illness is the cornerstone of management. Specific antiparasitic treatment has traditionally been with metronidazole compounded into a liquid for young children, but the awful taste and frequent dosing often result in poor adherence. Nevertheless, published cure rates range from 80% to 100%. The taste issue, known adverse effects, and lack of FDA approval for giardia, have led to use of other drugs.5 One dose of tinidazole is as effective as metronidazole and can be prescribed for children 3 years old or older. But the drug nitazoxanide is becoming more standard. It is as effective as either alternative, and is FDA approved for children 1 year old and older. Nitazoxanide also is effective against other intestinal parasites (e.g., cryptosporidium). Nitazoxanide’s 3-day course involves every-12-hour dosing with food with each dose being 5 mL (100 mg) for 1- to 3-year-olds, 10 mL (200 mg) for 4- to 11-year-olds, and one tablet (500 mg) or 25 mL (500 mg) for children 12 years old or older.6

Key elements in this subacute nonsystemic diarrheal presentation were primitive camping history, multiple stream water contacts, nearly 2 weeks of symptoms, weight loss, and flatulence/cramping, but no fever or stool blood/mucous. Two friends also appear to be similarly symptomatic, so a common exposure seemed likely This is typical for several summertime activity–related parasites. So,

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Diagnosis and Treatment Information for Medical Professionals, Giardia, Parasites. CDC.

2. Krumrie S et al. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2022;2:100084. doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2022.100084.

3. Baldursson S and Karanis P. Water Res. 2011 Dec 15. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.013.

4. “Water on the Appalachian Trail” AppalachianTrail.com.

5. Giardiasis: Treatment and prevention. UpToDate.

6. Kimberlin D et al. Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021. 32nd ed.) Giardia duodenalis infections. pp. 335-8; and p. 961 (Table 4.11).

It’s “summertime and the livin’ is easy” according to the lyric from an old George Gershwin song. But sometimes, summer activities can lead to illnesses that can disrupt a child’s easy living.

Case: An otherwise healthy 11-year-old presents with four to five loose stools per day, mild nausea, excess flatulence, and cramps for 12 days with a 5-pound weight loss. His loose-to-mushy stools have no blood or mucous but smell worse than usual. He has had no fever, vomiting, rashes, or joint symptoms. A month ago, he went hiking/camping on the Appalachian Trail, drank boiled stream water. and slept in a common-use semi-enclosed shelter. He waded through streams and shared “Trail Magic” (soft drinks being cooled in a fresh mountain stream). Two other campers report similar symptoms.

Differential diagnosis: Broadly, we should consider bacteria, viruses, and parasites. But generally, bacteria are likely to produce more systemic symptoms and usually do not last 12 days. That said, this could be Clostridioides difficile, yet that seems unlikely because he is otherwise healthy and has no apparent risk factors. Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and some Escherichia coli infections may drag on for more than a week but the lack of systemic symptoms or blood/mucous lowers the likelihood. Viral agents (rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, astrovirus, calicivirus, or sapovirus) seem unlikely because of the long symptom duration and the child’s preteen age.

The history and presentation seem more likely attributable to a parasite. Uncommonly detected protozoa include Microsporidium (mostly Enterocytozoon bieneusi) and amoeba. Microsporidium is very rare and seen mostly in immune compromised hosts, for example, those living with HIV. Amebiasis occurs mostly after travel to endemic areas, and stools usually contain blood or mucous. Some roundworm or tapeworm infestations cause abdominal pain and abnormal stools, but the usual exposures are absent. Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis, and/or Cystoisospora belli best fit this presentation given his hiking/camping trip.

Workup. Laboratory testing of stool is warranted (because of weight loss and persistent diarrhea) despite a lack of systemic signs. Initially, bacterial culture, C. difficile testing, and viral testing seem unwarranted. The best initial approach, given our most likely suspects, is protozoan/parasite testing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends testing up to three stools collected on separate days.1 Initially, stool testing for giardia and cryptosporidium antigens by EIA assays could be done as a point-of-care test. Such antigen tests are often the first step because of their ease of use, relatively low expense, reasonably high sensitivity and specificity, and rapid turnaround (as little as 1 hour). Alternatively, direct examination of three stools for ova and parasites (O&P) and acid-fast stain or direct fluorescent antibody testing can usually detect our main suspects (giardia, cryptosporidium, cyclospora, and cystoisospora) along with other less likely parasites.

Some laboratories, however, use syndromic stool testing approaches (multiplex nucleic acid panels) that detect over 20 different bacteria, viruses, and select parasites. Multiplex testing has yielded increased detection rates, compared with microscopic examination alone in some settings. Further, they also share ease-of-use and rapid turnaround times with parasite antigen assays while requiring less hands-on time by laboratory personnel, compared with direct microscopic examination. However, multiplex assays are expensive and more readily detect commensal organisms, so they are not necessarily the ideal test in all diarrheal illnesses.

Diagnosis. You decide to first order giardia and cryptosporidium antigen testing because you are highly suspicious that giardia is the cause, based on wild-water exposure, the presentation, and symptom duration. You also order full microscopic O&P examination because you know that parasites can “run in packs.” Results of testing the first stool are positive for giardia. Microscopic examination on each of three stools is negative except for giardia trophozoites (the noninfectious form) in stools two and three.

Giardia overview. Giardia is the most common protozoan causing diarrhea in the United States, is fecal-oral spread, and like Shigella spp., is a low-inoculum infection (ingestion of as few as 10-100 cysts). Acquisition in the United States has been estimated as being 75% from contaminated water (streams are a classic source.2 Other sources are contaminated food (fresh produce is classic) and in some cases sexual encounters (mostly in men who have sex with men). Most detections are sporadic, but outbreaks can occur with case numbers usually below 20; 40% of outbreaks are attributable to contaminated water or food.3 Evaluating symptomatic household members can be important as transmission in families can occur.

After ingestion, the cysts uncoat and form trophozoites, which reside mostly in the small bowel (Figure), causing inflammation and altering gut membrane permeability, thereby reducing nutrient absorption and circulating amino acids. Along with decreased food intake, altered absorption can lead to weight loss and potentially reduce growth in young children. Some trophozoites replicate while others encyst, eventually passing into stool. The cysts can survive for months in water or the environment (lakes, swimming pools, and clear mountain streams). Giardia has been linked to beavers’ feces contaminating wild-water sources, hence the moniker “Beaver fever” and warnings about stream water related to wilderness hiking.4

Management. Supportive therapy as with any diarrheal illness is the cornerstone of management. Specific antiparasitic treatment has traditionally been with metronidazole compounded into a liquid for young children, but the awful taste and frequent dosing often result in poor adherence. Nevertheless, published cure rates range from 80% to 100%. The taste issue, known adverse effects, and lack of FDA approval for giardia, have led to use of other drugs.5 One dose of tinidazole is as effective as metronidazole and can be prescribed for children 3 years old or older. But the drug nitazoxanide is becoming more standard. It is as effective as either alternative, and is FDA approved for children 1 year old and older. Nitazoxanide also is effective against other intestinal parasites (e.g., cryptosporidium). Nitazoxanide’s 3-day course involves every-12-hour dosing with food with each dose being 5 mL (100 mg) for 1- to 3-year-olds, 10 mL (200 mg) for 4- to 11-year-olds, and one tablet (500 mg) or 25 mL (500 mg) for children 12 years old or older.6

Key elements in this subacute nonsystemic diarrheal presentation were primitive camping history, multiple stream water contacts, nearly 2 weeks of symptoms, weight loss, and flatulence/cramping, but no fever or stool blood/mucous. Two friends also appear to be similarly symptomatic, so a common exposure seemed likely This is typical for several summertime activity–related parasites. So,

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Diagnosis and Treatment Information for Medical Professionals, Giardia, Parasites. CDC.

2. Krumrie S et al. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2022;2:100084. doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2022.100084.

3. Baldursson S and Karanis P. Water Res. 2011 Dec 15. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.013.

4. “Water on the Appalachian Trail” AppalachianTrail.com.

5. Giardiasis: Treatment and prevention. UpToDate.

6. Kimberlin D et al. Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021. 32nd ed.) Giardia duodenalis infections. pp. 335-8; and p. 961 (Table 4.11).